Paper Menu >>

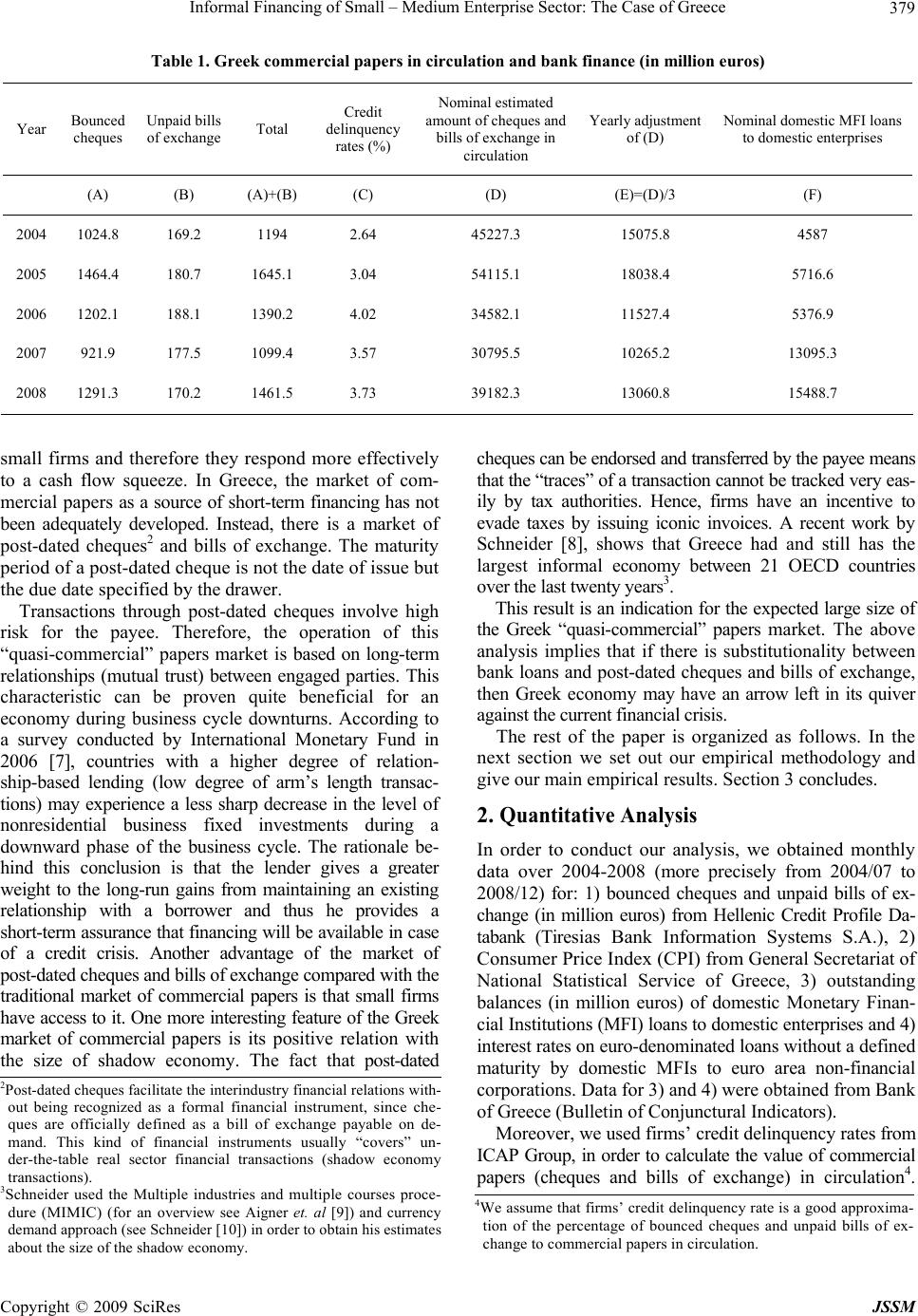

Journal Menu >>

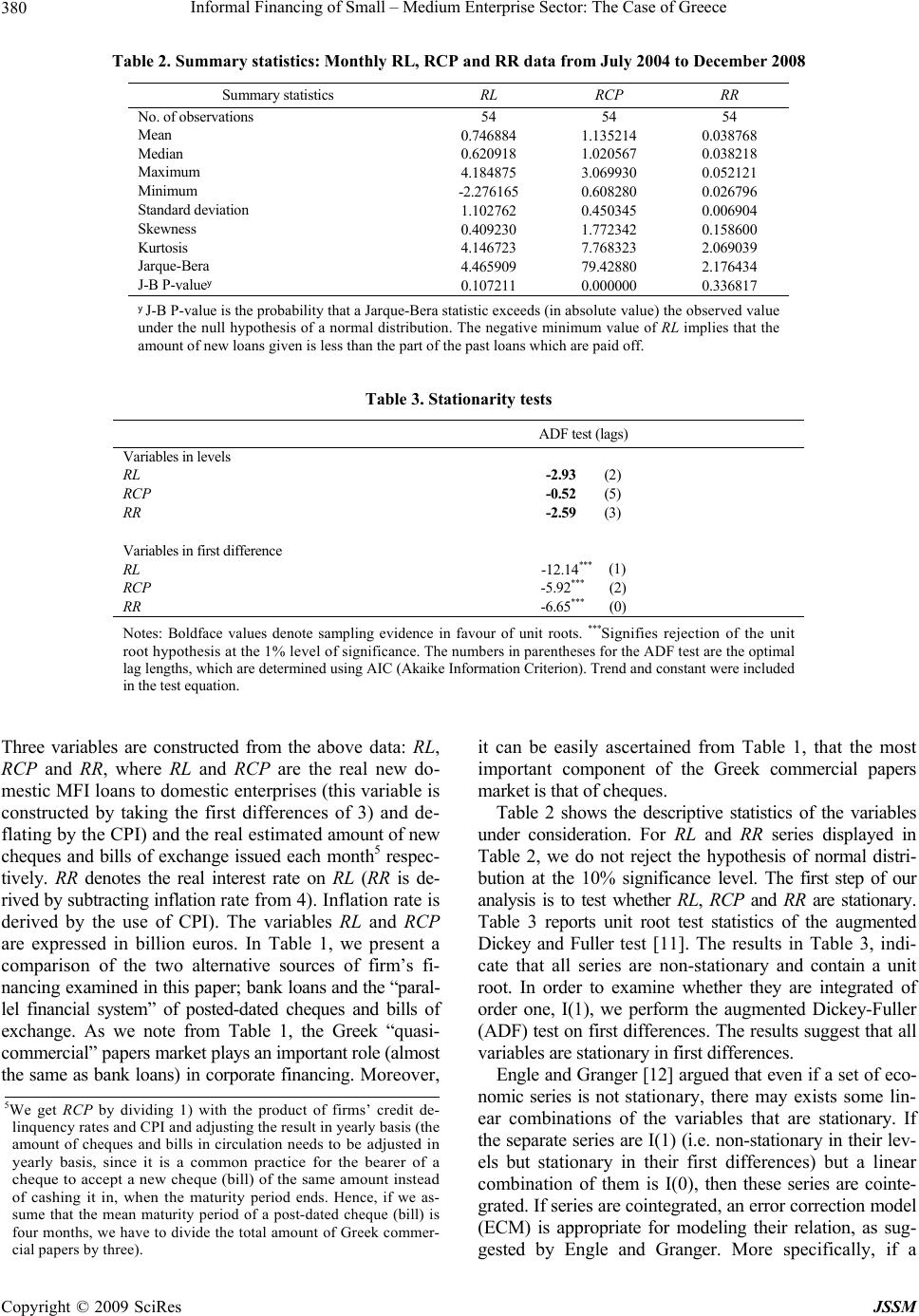

J. Service Science & Management, 2009, 2: 378-383 doi:10.4236/jssm.2009.24045 Published Online December 2009 (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM Informal Financing of Small – Medium Enterprise Sector: The Case of Greece Panagiotis Petrakis 1,*, Konstantinos Eleftheriou 2 1Department of Economics, University of Athens, Stadiou Street, Athens, Greece; 2D epartment of Economics, University of Piraeus, Karaoli & Dimitriou St reet, Piraeus, Greece. Email: ppetrak@econ.uoa.gr, kostasel@otenet.gr Received July 17, 2009; revised August 23, 2009; accepted September 29, 2009. ABSTRACT In this paper, we attempt to find a “ channel ” through which Greek economy can exhibit a relative “ resistance ” in a credit crunch. For this purpose, we specify an error correction model so as to test the relation ship between corpo- rate bank loans and commercial papers comprised of post-dated cheques and bills of exchange. The results show that corporate bank loans and cheques - bills of exchange are substitutes. This finding combined with the fact that in Greece, the issuance of these papers is positively connected with the informal economic activity which in turn rises dur- ing economic downturns, has a strong economic implication regarding the ability of Greek economy to partly “ amor- tize ” the shocks connected with the current financial crisis. Keywords: Corporate Finance, Credit Crunch, Shadow Financing 1. Introduction Is there an interrelation betw een bank loans and commer- cial papers (cheques, bills of exchange) as a source of ex- ternal debt financing for firms in Greek economy, and if yes, are they substitutes or complements? Which is the economic intuition between such an interrelation and can it offer a safety net to the current credit crunch? These are the main crucial questions we try to answer in this paper. One of the main factors which determine the level of “resistency” of an economy in a bank credit crunch is the ability of the economic system to cre ate multiple “chan- nels” of financing and exploit them properly. In modern economies, firms have a variety of debt financing tools at their disposal. However, each of these tools has a different rank in firm’s preferences. According to the traditional “pecking order” hypothesis of corporate finance [1], bor- rowing firms prefer to finance their debts through external resources (securities, bank loans) rather than equity issu- ance. Equity issuance is less preferred since the funds it provides are generally limited by the scale of expenditures (dividends) and it is considered by investors, as a “bad” signal for the economic performance and viability of the firm. Hence, firms mainly choose between bank b or ro w in g and debt securities issuance, when it comes to finance the ir co rp orate expenditures. Greenspan [2,3], emphasized the importance of such a choice under a credit crisis re- gime. More specifically, he suggested that there is a rate of substitutionality between the market of bank loans and that of bonds which smoo th es th e n ega tive imp act tha t a f ina n- cial crisis has o n real econo my. On th e o th er h an d , Ho lm- strom and Tirole [4], stressed that “multiple avenues of intermediation” (availability of t he aforementioned sources of external debt financing) for corporations are character- ized by complementarity. Their analysis is based on a principal-agent prob lem with monitoring costs. When the supply of intermediary capital falls due to a credit crunch, the q uantity of informed (banks) finance which is available to firms decreases. This also means that less uninformed (securities) finance can be attracted since the level of moni- toring undertaken is lower1. The findings of Holmstrom and Tirole [4], were empirically verified for U.S. economy by Davis and Ioannidis [ 5]. Gertler and Gilchrist [6], argu ed that the salutar y effects stemming from the substitutionality between the main al- ternative “chan nels” of corpor ate debt financing are limited when the market is dominated by small firms. This occurs, since large firms have access to short-term sources of redit (e.g. commercial papers market) unavailable to *This paper is based on an ongoing research project titled: “Economic Growth and Development in the Greek Economy”. We would like to thank an anonymous referee for useful comments and suggestions. Any remaining errors are ours. 1Uninformed investors are less willing to offer their funds when the level of monitoring connected with the informed finance is low. c  Informal Financing of Small – Medium Enterprise Sector: The Case of Greece379 Table 1. Greek commercial papers in circulation and bank finance (in million euros) Year Bounced cheques Unpaid bills of exchange Total Credit delinquency rates (%) Nominal estimated amount of cheques and bills of exchange in circulation Yearly adjustment of (D) Nominal domestic MFI loans to domestic enterprises (A) (B) (A)+(B) (C) (D) (E)=(D)/3 (F) 2004 1024.8 169.2 1194 2.64 45227.3 15075.8 4587 2005 1464.4 180.7 1645.1 3.04 54115.1 18038.4 5716.6 2006 1202.1 188.1 1390.2 4.02 34582.1 11527.4 5376.9 2007 921.9 177.5 1099.4 3.57 30795.5 10265.2 13095.3 2008 1291.3 170.2 1461.5 3.73 39182.3 13060.8 15488.7 small firms and therefore they respond more effectively to a cash flow squeeze. In Greece, the market of com- merc ial pap ers as a source of short-term financing has not been adequately developed. Instead, there is a market of post-dated cheques2 and bills of exchange. The maturity period of a post-dated cheque is not the date of issue but the due date specified by the drawer. Transactions through post-dated cheques involve high risk for the payee. Therefore, the operation of this “quasi-commercial” papers market is based on long-term relationships (mutual trust) between engaged parties. This characteristic can be proven quite beneficial for an economy during business cycle downturns. According to a survey conducted by International Monetary Fund in 2006 [7], countries with a higher degree of relation- ship-based lending (low degree of arm’s length transac- tions) may experience a less sharp decrease in the level of nonresidential business fixed investments during a downward phase of the business cycle. The rationale be- hind this conclusion is that the lender gives a greater weight to the long-run gains from maintaining an existing relationship with a borrower and thus he provides a short-term assurance that financing will be available in case of a credit crisis. Another advantage of the market of post-dated cheques and bills of exchange compared with the traditional market of commercial papers is that small firms have ac cess to it. On e more intere sting featur e of the Greek market of commercial papers is its positive relation with the size of shadow economy. The fact that post-dated cheque s can b e endors ed an d tra n sf err ed by th e pa yee me a n s that the “traces” of a trans action canno t be tracked very eas- ily by tax authorities. Hence, firms have an incentive to evade taxes by issuing iconic invoices. A recent work by Schneider [8], shows that Greece had and still has the largest informal economy between 21 OECD countries over the last twenty years3. This result is an indication for the expected large size of the Greek “quasi-commercial” papers market. The above analysis implies that if there is substitutionality between bank loans and post-dated cheques an d bills of exchange, then Greek economy may have an arrow left in its quiver against the current financial crisis. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section we set out our empirical methodology and give our main empirical results. Section 3 concludes. 2. Quantitative Analysis In order to conduct our analysis, we obtained monthly data over 2004-2008 (more precisely from 2004/07 to 2008/12) for: 1) bounced cheques and unpaid bills of ex- change (in million euros) from Hellenic Credit Profile Da- tabank (Tire sias Bank Information Systems S.A.), 2) Consumer Price Index (CPI) from General Secretariat of National Statistical Service of Greece, 3) outstanding balances (in million euros) of domestic Monetary Finan- cial Institut ions (MFI) loans to domestic enterprises and 4) interest rates on euro-denominated loans w it h ou t a d e f in e d maturity by domestic MFIs to euro area non-financial corporations. Data for 3) and 4) were obtained from Bank of Greece (Bulletin of Conjunc tural Indic a tors). 2 Post-dated cheques facilitate the interindustry financial relations with- out being recognized as a formal financial instrument, since che- ques are officially defined as a bill of exchange payable on de- mand. This kind of financial instruments usually “covers” un- der-the-table real sector financial transactions (shadow economy transactions). 3 Schneider used the Multiple industries and multiple courses proce- dure (MIMIC) (for an overview see Aigner et. al [9]) and currency demand approach (see Schneider [10]) in order to obtain his estimates about the size of the shadow economy. Moreover, we used firms’ credit delinquency rates from ICAP Group, in order to calculate the value of commercial papers (cheques and bills of exchange) in circulation4. 4 We assume that firms’ credit delinquency rate is a good approxima- tion of the percentage of bounced cheques and unpaid bills of ex- change to commercial papers in circulation. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Informal Financing of Small – Medium Enterprise Sector: The Case of Greece 380 Table 2. Summary statistics: Monthly RL, RCP and RR data from July 2004 to December 2008 Summary statistics RL RCP RR No. of observations 54 54 54 Mean 0.746884 1.135214 0.038768 Median 0.620918 1.020567 0.038218 Maximum 4.184875 3.069930 0.052121 Minimum -2.276165 0.608280 0.026796 Stan dar d de via t io n 1.102762 0.450345 0.006904 Skewness 0.409230 1.772342 0.158600 Kurtosis 4.146723 7.768323 2.069039 Jarque-Bera 4.465909 79.42880 2.176434 J-B P-valuey 0.107211 0.000000 0.336817 y J-B P-value is the probability that a Jarque-Bera statistic exceeds (in absolute value) the observed value under the null hypothesis of a nor mal distribution. The negative minimum value of RL implies that the amount of new loans given is less than the part of the past loans which are paid off. Table 3. Stationarity tests ADF test ( lags) Variable s in le vels RL -2.93 (2) RCP -0.52 (5) RR -2.59 (3) Variables in first difference RL -12.14 *** (1) RCP -5.92*** (2) RR -6.65 *** (0) Notes: Boldface values denote sampling evidence in favour of unit roots. *** Signifies rejection of the unit root hypothesis at the 1% level of significance. The numbers in parentheses for the ADF test are the op timal lag lengths, which are determined using AIC (Akaike Information Criterion). Trend and constant were included in the test equation. Three variables are constructed from the above data: RL, RCP and RR, where RL and RCP are the real new do- mestic MFI loans to domestic enterprises (this variable is constructed by taking the first differences of 3) and de- flating by the CPI) and the real est imated amount of new cheques and bills of exchange issued each month5 respec- tively. RR denotes the real interest rate on RL (RR is de- rived by subtracting inflation rate fr om 4 ) . In fl at io n r at e is derived by the use of CPI). The variables RL and RCP are expressed in billion euros. In Table 1, we present a comparison of the two alternative sources of firm’s fi- nancing examined in this paper; bank loans and the “paral- lel financial system” of posted-dated cheques and bills of exchange. As we note from Table 1, the Greek “quasi- commercial” papers market plays a n importa nt ro l e (a lmost the same as bank loans) in corporate financing. Mo reo ver , it can be easily ascertained from Table 1, that the most important component of the Greek commercial papers market is that of cheques. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables under consideration. For RL and RR series displayed in Table 2, we do not reject the hypothesis of normal distri- bution at the 10% significance level. The first step of our analysis is to test whether RL, RCP and RR are stationary. Table 3 reports unit root test statistics of the augmented Dickey and Fuller test [11]. The results in Table 3, indi- cate that all series are non-stationary and contain a unit root. In order to examine whether they are integrated of order one, I(1), we perform the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test on first differences. The results suggest that all variables are stationary in first differences. Engle and Granger [12] argued that even if a set of eco- nomic series is not stationary, there may exists some lin- ear combinations of the variables that are stationary. If the separate series are I(1) (i.e. non-stationary in their lev- els but stationary in their first differences) but a linear combination of them is I(0), then these series are cointe- grated. If series are cointegrated, an error correction model (ECM) is appropriate for modeling their relation, as sug- gested by Engle and Granger. More specifically, if a 5 We get RCP by dividing 1) with the product of firms’ credit de- linquency rates and CPI and adjusting the result in yearly basis (the amount of cheques and bills in circulation needs to be adjusted in yearly basis, since it is a common practice for the bearer of a cheque to accept a new cheque (bill) of the same amount instead of cashing it in, when the maturity period ends. Hence, if we as- sume that the mean maturity period of a post-dated cheque (bill) is four months, we have to divide the total amount of Greek commer- cial papers by three). Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Informal Financing of Small – Medium Enterprise Sector: The Case of Greece381 t u group of variables is non-stationary (random walks), then by regressing one variable against the others can lead to spurious results in the sense that conventional signifi- cance tests will tend to indicate a relationship between the variables when in fact none exists. This problem can be solved if we use in our modeling process the first dif- ferences of the above variables after verifying that these differences are stationary (integrated of order one, I(1), variables). However, even though this approach is correct in the context of univariate modeling [e.g. Autoregres- sive – Moving Average (ARMA) processes], it is inad- visable when we try to examine the relationship between variables. The main drawback of this, in other respects, statistically valid app roach is th at it has no long-run solu- tion (common problem in pure first difference models). More specifically, one definition of the long run that is employed in econometrics implies that variables have converged upon some long term values and are no longer changing. Hence, all the first difference terms will be zero and by simply regressing the one against the others gives results which say nothing about whether the vari- ables under consideration have an equilibrium relation- ship. However, this problem can be overcome by using a combination of the first differenced and lagged levels of cointegrated variables. This formulation is known as an error correction model. Through this model, we can ex- amine the short run dynamic relationship between the variables under consideration by taking into account their deviations from their equilibrium/long run relationship (residuals of the cointegrating regression). In order to test for cointegration, we use the maximum likelihood methodology proposed by Johansen [13]. Ac- cording to Johansen a Vector Autoregression (VAR) model of order , can be written as follows: p 1 () ttpt YLYY (1) where is the vector of RL , RCP and RR , t Y 12 (, 3 , ) , ()L is a polynomial of order 1p , is a vector of independent Gaussian errors with zero mean and covariance matrix , is th e first difference operator and t u is a matr ix of the form where and are 3×r matrices each with rank r, with being the matrix of the r cointegrating vectors (i.e. the columns of represent the r cointegrating relations) and being the matrix of adjustment coefficients. As stated above, the existence of cointegration has implica- tions about the way we should model the relationships between RL and RCP, RR. The results of Johansen cointegration test are pre- sen ted in Tab le 4. S ince Johansen’s procedure is sensitive to the lag length of the Vector Autoregression (VAR) (Banerjee et al. [14]), we determine the lag length by us- ing the appropriate criteria. The max eigenvalue statistic supports the existence of one cointegrating vector. More specifically, the cointe- grating equation is: 1.23 35.52RLRCP RR (2) This finding implies that there is a long run equilibrium relat ionship betw een RL, RCP and RR. Equation (2) indi- cates that the real value of newly issued Greek commer- cial papers in circulation and the real interest rates of corporate bank loans are negatively correlated to the real amount of corporate bank loans (in the long-run), with the estimated coefficients of -1.23 and -35.52, respectively. Table 4. Johansen cointegration test Hypothesized # of cointegrated equations (r) Max eigenvalue statistic Critical values at 5% None 31.99**21.13 At most 1 4.4514.26 At most 2 2.883.84 Note: ** Indicates the rejection of the hypothesis about the number of cointegrated equations at the 5% level. The sequential modified LR test statistic, the final prediction error (FPE) and the Schwarz information criterion indi- cate that the optimal lag length of the VAR is equal to one. Moreover, the VAR residual Portmanteau test for autocorrelations does not reject the null hypothesis of no r e sidual aut ocorrelations. Table 5. TSLS estimates of the ECM Parameter Coefficient t-value -0.075 -0.364 0 -2.66** -2.049 0 -56.92 -0.39 1 -1.2*** -7.026 2 R 0.56 Note: *** and ** denote statistical significance at 1% and 5%, respectively. The following series were used as instru- ments: constant. 161214 121 12 ,, ,,,,, tttttt tt ECT ECT ECTRCPRCPRLRRRR , Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Informal Financing of Small – Medium Enterprise Sector: The Case of Greece 382 Table 6. Diagnostic tests Value of test statistic P-value JB 5.295 [0.071] Reset test 0.455 [0.504] Hansen’ s J statistic test 5.449 [0.363] 1 /2 L MLM test 0.071/1.212 [0.789/0.545] BDS test Dimension 2 -0.0053 [0.7908] 3 -0.01389 [0.2847] 4 -0.00601 [0.5855] 5 -0.00222 [0.8633] 6 -0.00329 [0.3745] Note: Figures in brackets represent asymptotic P – values associated with the tests. JB denotes the Jarque-Bera normality test of errors. The Reset test tests the null hypothesis of functional form misspecification. 1 /2 L MLMis the Lagrange multiplier test for first and second order serial correlation (under the null there is no serial correlation in the residuals up to the specified order). Hansen’ s J statistic test is a general version of the Sargan test, a test of overidentifying restric- tions (under the null hypothesis the overidentifying restrictions are satisfied). For the relationship between J statistic and Sargan test see Murray [15]. Finally the BDS [16] test tests the null hypothesis that the errors are independently and identically distributed (In our test we set the value of distance between the pair of the elements of a time series, equal to 0.7. Since our sample is relatively small, we use boo tstrap P - values ). As RL, RCP and RR are cointegrated, it is necessary to specify an ECM in order to examine the short-run rela- tionship of these variables. We specify an error correction model of the followi ng type: 110 0ttt RLECTRCP RRtt t = 1, 2, …. T (3) where ECT is the error correction term and t is a dis- turbance term. Since and current values appear in the above equation, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimation produces inconsistent estimators. In or de r t o o ve r come this problem, w e apply a two stag e leas t squares (TSLS) estimation procedure. Table 5 presents the TSLS estimates of Equation (3). Moreover, we check the specification of our estimated model by performing various diagnostic tests. These tests are reported in Table 6. Our results indicate that th e ECM seems to be quite well speci- fied and free from specification error. t RCPt RR As we note from Table 5, the coefficient of the ECT has the correct sign, is statistically significant and is rather large indicating rapid adjustment of RL, RCP and RR to the proceeding imbalance () in a short ru n period. In order to investigate the relationship between the provi- sion of corpora te bank loans and issuance of cheques and bills, we turn our attention to the short-run elasticity . 1t ECT Table 5, indicates that γ0 is negative and statistically sig- nificant. More specifically, if the issuance of new Greek commercial papers increases by 100 million euros then the provision of corporate bank loans decreases, ceteris paribus, by 266 million euros within a month. This find- ing implies that there is substitutionality between bank loans and post-d ated cheques and bills of exch ange. If we take into consideration that during a credit crunch, there are bank credit shortages, there is a tendency for informal economy to increase [17] and the fact that (as mentioned above) there is a positive relation between the size of Greek commercial papers market and that of shadow economy, then we conclude that Greek economy may alleviate the negative impact of economic downturns caused by finan- cial crisis. 3. Conclusions and Policy Implications In our analysis, we showed that the Greek market of cheques and bills of exchange can serve as a substitute for bank loans. By combining this result with the distinctiveness in the structure of the commercial papers market in Greece, whi ch allows small firms to have access to short-term fund- ing and the close connection of the size of this market with that of informal economy, we can argue that Greek economy can partly “amortize” the shocks connected with the current financial crisis. Thus, monetary policy exhibits only indi- rect effects on real enterprise sector. In case of an interest rate fall, someone would expect that the positive effects will find the way out to the real sector. On the other hand, when interest rates rise during a credit crunch due to the segmentation of the financial sector (low interbank and interindustry trustiness), the enterprise sector will substi- tute the absence of financial credit with interindustry fi- nancing. Therefore, the IMF argument, that economies with low degree of arm’s length transactions can smooth the negative credit crunch effects and regenerate economic activity during the easing of a credit crisis, is confi rmed. The main deficiency of our analysis is that, although we Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Informal Financing of Small – Medium Enterprise Sector: The Case of Greece383 have developed our arguments about the positive relation be t w e e n Greek market of ch eques and b ills of exch ange a n d informal economic activity by citing the appropriate refer- ences, we have not explicitly included the underground economy in our analysis. The estimation and the inclusion of a variable indicating t he size of the informal economy in our model can further enhance the robustness of our ana- lytical results. Moreover, the use of dummy variables which will capture the relevant effects during periods of economic turbulence and the expansion of o ur dat a set so as to include the latest available data, will also reinforce our conclusions. All these issues can be considered as topics for future research. REFERENCES [1] S. Myers, “The capital structure puzzle,” Journal of Fi- nance, Vol. 39, pp. 575–592, 1984. [2] A. Greenspan, “Do efficient financial markets mitigate fi- nancial crises?” Speech to the Financial Markets Conference of the Federal Reserv e Bank of Atlan ta, 1999. [3] A. Greenspan, “Global challenges,” Speech to the Financial Crisis Conference, C o u n c il on Foreign Relations, New York, 2000. [4] B. Holmstrom and J. Tirole, “Financial intermediation, loanable funds, and the real sector,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 112, pp. 663–691, 1997. [5] P. Davis and C. Ioannidis, “External financing of US cor- porations: Are loans and securities complements or substi- tutes?” Economics and Finance Discussion Papers, Brunel Univ er si t y, 2004. [6] M. Gertler and S. Gilchrist, “Monetary policy, business cycles, and the beha vi or of sma ll man ufact uri ng fi rms, ” Th e Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 109, pp. 309–340, 1994. [7] World Economic Outlook, “How do financial systems affect economic cycles?” International Monetary Fund, 2006. [8] F. Schneider, “The size of the shadow economy in 21 OECD countries (in % of ‘official’ GDP) using the MIMIC and currency demand approach: From 1989/90 to 2009,” Working paper, Johannes Kepler University, 2009, (http://www.economics.unilinz.ac.at/members/Schneider/f iles/publications/ShadowEconomy21OECD_2009.pdf). [9] D. Aigner, F. Schneider, and D. Ghosh, “Me and my shadow: Es timating the size of the US hidden economy from time series data,” In W. A. Barnett, E. R. Berndt, and H. White, (edition), Dynamic Econometric Modeling, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (Mass.), pp. 224–243, 1988. [10] F. Schneider, “Size and measurement of the informal economy in 110 countries around the world,” The World Bank: Rapid Response Unit, Washington D.C., 2002. [11] D. A. Dickey and A. M. Fuller, “Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root,” Economet- rica, Vol. 49, pp. 1057–1072, 1981. [12] R. F. Engle and C. W. G. Granger, “Co-integration and er- ror correction representation, estimation and testing,” Econometrica, Vol. 55, pp. 251–276, 1987. [13] S. Johansen, “Statistical analysis of cointegration vec- tors,” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 12, pp. 231–254, 1988. [14] A. Banerjee, J. J. Dolado, F. D. Hendry, and G. W. Smith, “Exploring equilibrium relations in econometrics through state models: So me monte carlo evidence,” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 48, pp. 253–278, 1986. [15] M. Murray, “Avoiding invalid instruments and coping with weak instruments,” Journal of Economic Perspec- tives, Vol. 20, pp. 111–132, 2006. [16] W. A. Brock, W. Dechert, and J. Scheinkman, “A Test for independence based on the correlation dimension,” Eco- nometrics Reviews, Vol. 15, pp. 197–235, 1996. [17] The Economist, “The black market: Notes from the un- derground”, 2 April 2009. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM |