Paper Menu >>

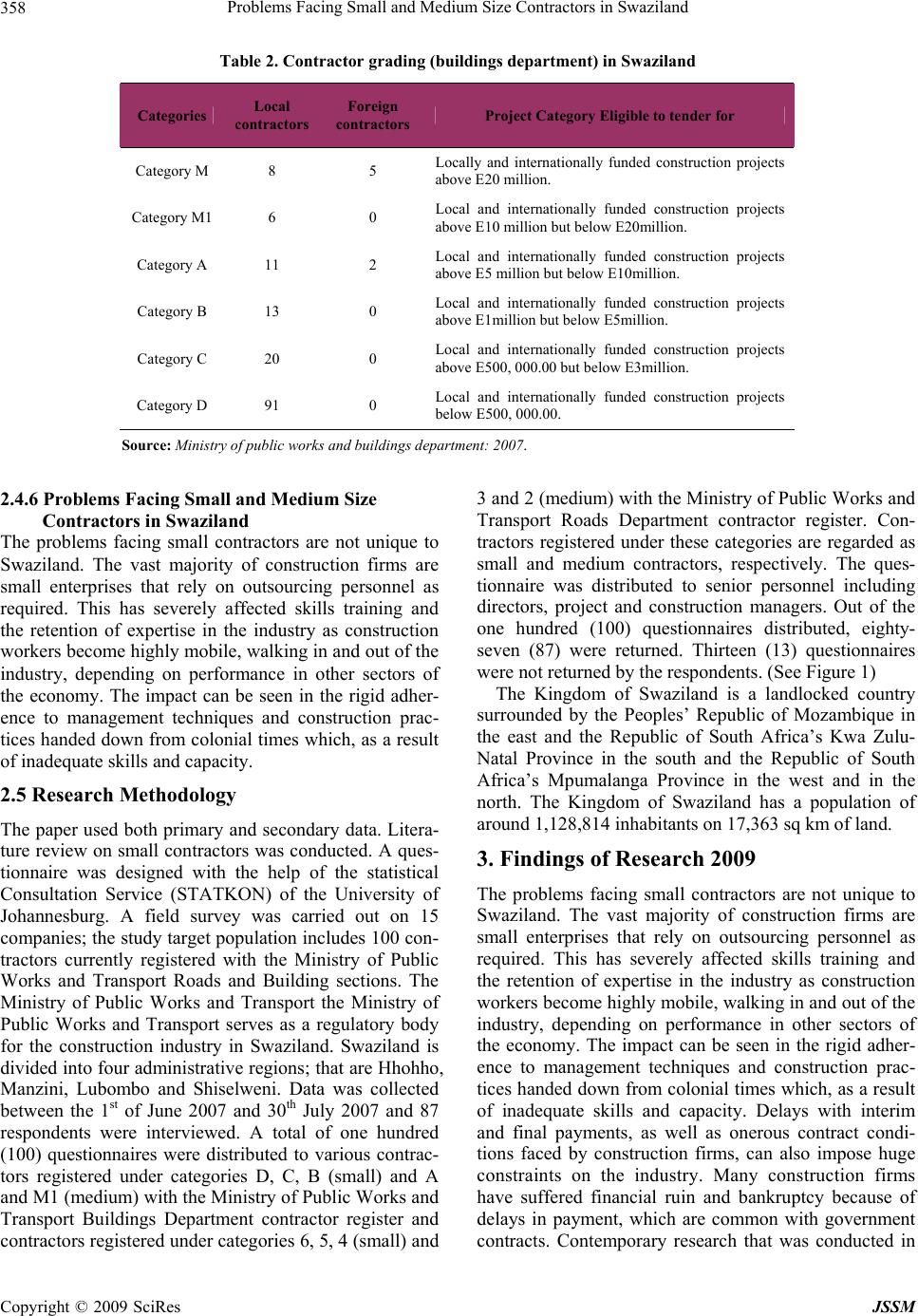

Journal Menu >>

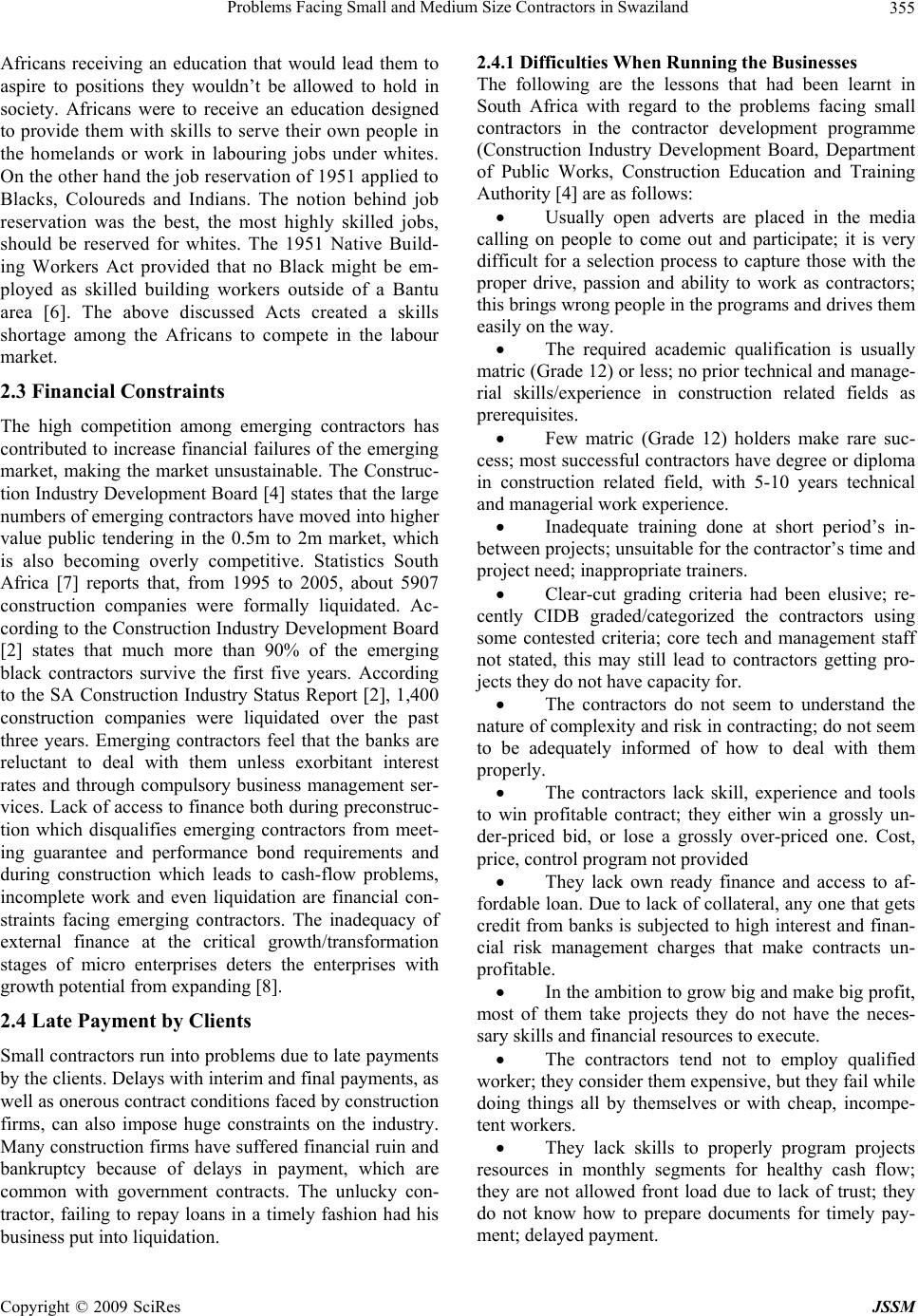

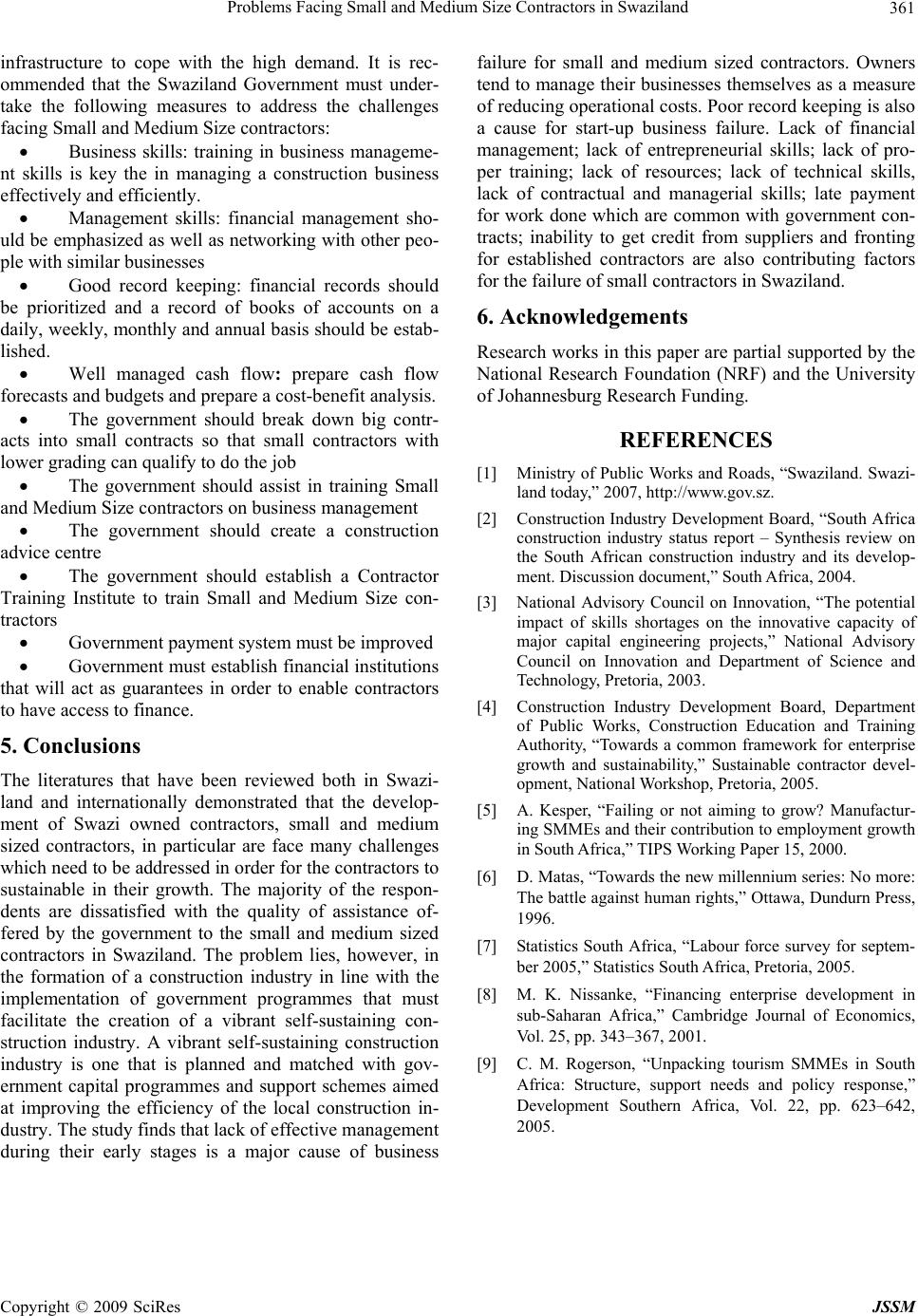

J. Service Science & Management, 2009, 2: 353-361 doi:10.4236/jssm.2009.24042 Published Online December 2009 (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 353 Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland Wellington Didibhuku Thwala1, Mpendulo Mvubu2 1Department of Quantity Surveying and Construction Management, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa; 2Department of Construction Management and Quantity Surveying, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. Em ail: didibhukut@uj.ac.za Received June 20, 2009; revised August 1, 2009; accepted September 19, 2009. ABSTRACT The paper explores the problems facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland. The construction sector in Swaziland is not only a significant source of direct employment but also a sector which contributes, through its wide range of projects and operations. The paper will also look at the current government initiatives that had been put in place to address the challenges and problems in order to ensure that contractors are successful. There is a high failure rate among small and medium size contractors in Swaziland. These contractors fail for a variety of reasons ranging from lack of adequate capacity to hand le the uniqueness, complexity and risks in contracting , lack of effective manage- ment, lack of business management, poor record keeping and inadequate technical, financial and contract managerial skills. Drawing on research on small and medium size contractors, the paper used both secondary and primary litera- ture. 100 questionna ires were distributed to different role players in the con struction secto r in Swaziland . The response rate was eighty seven (87) percent. The paper reveals that the most problems facing small and medium size contractors in Swaziland is lack of access to finance and late payment by government. The paper closes with recommendations and key lessons for the future. Keywords: Contractor, Construction, Employment, Small and Medium Size, Public Works 1. Introduction In Swaziland and other countries there seem a general consensus that small enterprises are the mainstay of eco- nomic growth and prosperity. Small contractors can be powerful instruments of generating job opportunities; small contractors can perform small projects at different and remote geographical locations that might be unat- tractive to big firms or too costly using the big firms; low overheads enable small contractors to work at more competitive prices; large number of functional small and medium scale black contractors can help to decentralise the construction industry dominated by established large contractors; the relatively low skills and resources re- quired at this scale can easily lower the entry point for the small and medium size owners to begin to participate in the industry; and a large number of functional Swazi owned contractors can develop a platform for growth and redistribution of wealth in Swaziland. Small and Medium Size contractors in Swaziland are defined as those con- tractors who do work up to E20 millio n (Exchange Rate: $1 = E8). At a time when the public sector and big busi- ness are shedding jobs, small businesses are maintaining real employment growth. The small contractor develop- ment programme falls under the Ministry of Public Works and Transport. The main mandate of the ministry is to ensure the provision and maintenance of a sustain- able public infrastructure, an efficient and effective seamless transport system and network, regulation for a vibrant construction and transport industry, management of public service accommodation and the provision of meteorological services [1]. 2. Research Objectives The main objective of this paper is to outline the prob- lems faced by small and medium size contractors in the Kingdom of Swaziland. 2.1 Review of South African Literature 2.1.1 Skill Development in the Construction Industry Historically, the construction industry has largely relied on a core of highly skilled staff (generally white and of- ten expatriate) to supervise a largely semi-skilled and unskilled workforce (generally black). The decline in demand for construction products over the past decades, and associated uncertainty, has seen a reduction in skills  Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland 354 training since the 1980s, and the closing down of indus- try training institution s in the 1990s. It has been reported that only about 70 percent of the available training ca- pacity is currently being utilized [2]. Skills enhancement in the construction industry faces a very particular chal- lenge since the construction sector employs the fourth highest number of persons having no formal education – after agriculture, households and mining. Industry has expressed a view that skills supplied to the market through the Further Education and Training (FET) sys- tem were in many cases not appropriate to their needs, resulting in a skills gap. While industry-based training is seen as better aligned with company-specific require- ments, South African Qualification Authority (SAQA) does not accredit some trainers, and some do not issue certificates for training and employment. This tendency limits mobility and career path prospects [2]. The important note was to recognize the improvement of the work skills of all South Africans, which is critical to grow the national economy. The Skills Development Act (SDA) was promulgated to create the structures and framework for the national development strategy. In terms of the SDA employers are obliged to provide for- mal structured education to their workers, hence in the problem statement one looks at the possibilities of the employed trained people by Group Five being given the opportunity to further their training. Furthermore, the act encourages partnership in this ef- fect between government, employers, workers, education and training providers, and beneficiary co mmunities. The trained people are the beneficiaries from the community. According to SDA, the needs of employers, the economy and the communities must dictate which skills develop- ment should be developed. The part of which skills should be develop ed lead one to the last objectives in th e problem statement to try to iden tify which skills are often needed in different trades and provinces. The SDA covers structured, targeted and generic training implying that all training interven tions should be planned and managed as projects that is the reason why Group Five has “people at the gate” which is Corporate Social Investment Project. In SDA, employers together with their workers formulate workplace skills plan (WSP) to enable them to realize their employment training tar- gets. All designated employers pay a monthly skills de- velopment levy of 1% of their budgeted payrolls to the National Skills Fund (NFS), via South African Revenue services (SARS). Of this amount, the employer can claim back 70% in the form of discretionary grant, provided that they submit WSP and Implementation Report (IR) annually and conduct special training projects. These levies finance the implementation of the Na- tional Skills Development Strategy (NSDS). Construc- tion Education and training Authorities (CETA) receives 10% of the skills levies paid by construction employers for administration costs, NSF receives 20%, and 70% is available to be claimed back by these contributing em- ployers. However, international trends shows that com- panies need to spend between 4% and 7% in order to be successful in addressing the current shortages and gaps [3]. Furthermore, there appears to be over-reliance of a number of levels in the micro and provincial economy on the SETA’s as being responsible bodies for coordinating the identification of scare skills in South Africa. 2.2 Small Contractors in South Africa In South Africa, the contractors enter the market at the lower end and in the general building contracting cate- gory, making the sector extremely competitive and un- sustainable [4] and the emerging contractor policies in- tended for black economic empowerment (BEE) are be- ing used as job creation opportunities, which contributes to the over crowding of the emerging market. It is com- mon for black businesses to be based on technical skills which are based on technical skills, which are used to satisfy needs of the community. However, technical competence is no guarantee of business success. Opera- tional (e.g. scheduling and ordering) and business (e.g. planning, financial control and budgeting) skills are vital to the success of any enterprise. Small enterprises con- tribute positively to the economics of the country and to the survival of large numbers of people. 2.2.1 Skills Shortage in Small Contra ctors South Africa is characterized by a systematic under- investment in human capital. This has resulted in a la- bour force with a skewed distribution of craft skills, ca- reer opportunities and work-place experience. While the promulgation of the Skills Development Act of 1997 is commendable, micro enterprises already express concern about the administration costs of recovering levies in the form of grants for training. Furthermore, there are the costs of designing a workplace training programme as an alternative to using external training institutions and the relatively high charges by private training institutions after the closure of the former industrial training boards which had been subsidized through levies from industry [5]. The imbalances of the past with regard to the school curriculum known as “Bantu education” which did not offer much mathematic and science as part of the cur- riculum hinder the emerging market as these subjects are essential for entry into the engineering and built envi- ronment industry. This Bantu system secured the exclu- sion of black people from participating in the construc- tion industry as they did not have the necessary skills required. According to Matas [6] the Bantu Education Act, Act No. 47 of 1953 established a Black Education Department in the Department of Native Affairs which would compile a curriculum that suited the nature and requirements of black people. The aim was to prevent Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland355 Africans receiving an education that would lead them to aspire to positions they wouldn’t be allowed to hold in society. Africans were to receive an education designed to provide them with skills to serve their own people in the homelands or work in labouring jobs under whites. On the other hand the job reservation of 1951 applied to Blacks, Coloureds and Indians. The notion behind job reservation was the best, the most highly skilled jobs, should be reserved for whites. The 1951 Native Build- ing Workers Act provided that no Black might be em- ployed as skilled building workers outside of a Bantu area [6]. The above discussed Acts created a skills shortage among the Africans to compete in the labour market. 2.3 Financial Constraints The high competition among emerging contractors has contributed to increase financial failures of the emerging market, making the market unsustainable. The Construc- tion Industry Development Board [4] states that the large numbers of emerging contractors have moved into higher value public tendering in the 0.5m to 2m market, which is also becoming overly competitive. Statistics South Africa [7] reports that, from 1995 to 2005, about 5907 construction companies were formally liquidated. Ac- cording to the Construction Industry Development Board [2] states that much more than 90% of the emerging black contractors survive the first five years. According to the SA Construction Industry Status Report [2], 1,400 construction companies were liquidated over the past three years. Emerging contractors feel that the banks are reluctant to deal with them unless exorbitant interest rates and through compulsory business management ser- vices. Lack of access to finance both during preconstruc- tion which disqualifies emerging contractors from meet- ing guarantee and performance bond requirements and during construction which leads to cash-flow problems, incomplete work and even liquidation are financial con- straints facing emerging contractors. The inadequacy of external finance at the critical growth/transformation stages of micro enterprises deters the enterprises with growth potential from expanding [8]. 2.4 Late Payment by Clients Small contractors run into problems due to late payments by the clients. Delays with interim and final payments, as well as onerous contract conditions faced by construction firms, can also impose huge constraints on the industry. Many construction firms have suffered financial ruin and bankruptcy because of delays in payment, which are common with government contracts. The unlucky con- tractor, failing to repay loans in a timely fashion had his business put into liquidation. 2.4.1 Difficulties When Running the Businesses The following are the lessons that had been learnt in South Africa with regard to the problems facing small contractors in the contractor development programme (Construction Industry Development Board, Department of Public Works, Construction Education and Training Authority [4] are as follows: Usually open adverts are placed in the media calling on people to come out and participate; it is very difficult for a selection process to capture those with the proper drive, passion and ability to work as contractors; this brings wrong people in the programs and drives them easily on the way. The required academic qualification is usually matric (Grade 12) or less; no prior technical and manage- rial skills/experience in construction related fields as prerequisites. Few matric (Grade 12) holders make rare suc- cess; most successful contractors have degree or diploma in construction related field, with 5-10 years technical and managerial work experience. Inadequate training done at short period’s in- between projects; unsuitable for the contractor’s time and project need; inappropriate trainers. Clear-cut grading criteria had been elusive; re- cently CIDB graded/categorized the contractors using some contested criteria; core tech and management staff not stated, this may still lead to contractors getting pro- jects they do not have capacity for. The contractors do not seem to understand the nature of complexity and risk in contracting; do not seem to be adequately informed of how to deal with them properly. The contractors lack skill, experience and tools to win profitable contract; they either win a grossly un- der-priced bid, or lose a grossly over-priced one. Cost, price, control program not provided They lack own ready finance and access to af- fordable loan. Due to lack of collateral, any one that gets credit from banks is subjected to high interest and finan- cial risk management charges that make contracts un- profitable. In the ambition to grow big and make big profit, most of them take projects they do not have the neces- sary skills and financial resources to execute. The contractors tend not to employ qualified worker; they consider them expensive, but they fail while doing things all by themselves or with cheap, incompe- tent workers. They lack skills to properly program projects resources in monthly segments for healthy cash flow; they are not allowed front load due to lack of trust; they do not know how to prepare documents for timely pay- ment; delayed payment. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland 356 They do not seem to understand terms of con- tract conditions; do not know how to use applicable con- tract performance procedure to deal with client; they do not get properly trained in this. They are usually considered incapable of doing competent work, which imperils their relationship with the client’s agent; they do not seem to know how to use applicable contractual instruments regarding instruction, demand for specific performance, and payment; they are not properly taught; where they know these rules they fail to use them due to fear of being ‘red listed’. In attempt to make huge profit they cut specified quality, do bad work that falls short of the design stan- dards/specification. Rejection of such works usually leads to none payment, conflict and most times failure of the contractors. Those that manage to win profitable contracts get only 2% profit if they are able to successfully com- plete the project; it seems discouraging. The studies show that enterprise success is greatly in- creased by having relatively stable access to markets and access to capital from external sources, and that suc- cessful enterprises are characterized by entrepreneurs with a basic level of education, essential technical knowledge and prev ious industry exp erience with larger enterprise, and ability to learn new skills, innovate and take risks [9]. 2.4.2 Review o f Literature – Swazi l and The Ministry of Public Works and Transport [1] is a ma- jor contributor in the Swaziland construction industry. The Ministry is Government’s implementing agency on behalf of all ministries with regard to all government construction capital projects. The role of the Swaziland Government through the Ministry of Public Works and Transport is to educate the small and medium contractors about government’s expectations to the tendering process and information required for qualification. Another im- portant aspect o f the dissemination of knowledg e to con- tractors is that of information on the standard of work- manship required in government projects. The Ministry of Public Works and Transport is responsible for initiat- ing; the payment process to contractors by preparing the monthly interim certificates. This is very important to contractors in that the speedy execution of payments will ensure that contractors are paid in time and their cash flow is not stretched to the limit. 2.4.3 The Construction Industry in Swaziland The Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland, through its 25-year National Development Strategy (NDS) has identified the construction sector as a priority area to impact on improving the social and economic develop- ment of the country. However, to maximize the impact of the sector as part of the NDS, it will be necessary to de- velop a sound national policy framework for the industry to improve its overall effectiveness and efficiency. Fun- damental to the policy and in line with the NDS, will be the empowerment of local Swazis within the industry to maximize their participation and consequent impact on the local economy. As far back as 1993, the Gov ernment, through the then Ministry of Public Works and Roads took the initiative to organize the Southern Africa Con- struction Industry Initiative (SACII) on behalf of ten countries of the Southern Africa Development Commu- nity (SADC) region. At that time, the overall objectives of the Initiative were to: Identify constraints to the development of local construction industries in each participating country within the region; Identify specific policy reform to improve the enabling environment for local construction industry growth and development; Implement reforms in member countries with Government and donor commitment to lo cal constructio n industry de velopm en t. In general, the main intention of the Initiative was to create jobs, develop local capability and empower lo- cal/indigenous companies in the construction industry and is directly in line with the policy framework re- quired by stakeholders in Swaziland. Hence, some of the recommendations and policy options developed as part of the 1993 initiative at national and regional level have been used as a foundation for the framework pre- sented here. 2.4.4 The Swaziland Construction Industry Policy The vision of the government of the Kingdom of Swazi- land, as stated in the Swaziland National Construction Industry Policy 2002 [1] advocates for “a construction industry that maximizes “local participation.” The con- struction industry is not only a considerable source of direct employment, but also an industry which contrib- utes to the overall economy of Swaziland, through its extensive assortment of projects and operations. Since the Swazi economy is unable to provide employment for the ever growing population in Swaziland, focus may be turned to the local construction industry. The contribu- tion of the construction industry to the Swazi economy comes in the form of job creation, development of local capability and the empowerment of local indigenous companies in the construction industry. The Swaziland Construction Industry Policy intended to create an enabling environment to best meet the needs of the stakeholder in the construction industry in Swazi- land and commits Government to various roles, functions and activities. In the past, Government’s role has been as a regulator and, in some cases, provider of physical in- frastructure with no holistic policy framework and stra- tegic plan to drive the industry. Through the policies de- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 357 veloped, Government intends to refocus its primary role to that of policy and strategy formulation, and regulation of the industry with a reduced direct involvement in the provision of infrastructure and serv ices. The implications are that the capacity and capabilities of the local private sector need to be developed to undertake some of the services previously carried out by Government. It is also the intention of Government to include other key role players in the co-ordination of the industry and the development of broader national strategies that may otherwise not be achieved successfully. A regulatory role will be retained by Government to ensure safety and quality of service through out the industry and to monitor progress in achieving the vision and mission of the in- dustry presented here. This will mean, a more focused and skilled national Government that can control, moni- tor and regulate the relationships between service pro- viders and implementing agencies. Government also recognizes that the local human re- source pool of the construction industry needs to be strengthened to achieve the vision and mission. It is also of concern that there is a significant loss of trained per- sonnel to improved opportunities in other countries. Hence, Government will assume a responsibility for em- powerment and capacity enhancement of the local indus- try through the retention of trained personnel and a gen- eral improvement of the resource pool in the industry. However, Government will also seek to involve the pri- vate sector in meeting the challenge of growing and re- taining the country’s human resource base. 2.4.5 Contractor Accreditation Process in Swaziland A registration of accredited construction enterprises in Swaziland constitutes an essential tool for the industry transformation, for monitoring the performance of ena- bling environment programmes, and for ensuring com- pliance with the performance of public-sector projects. All construction enterprises engaged in public sector work, or in receipt of State funding training or support functions, will be required to be registered in a manner that will reflect their capacity and performance. The reg- istration process must address the following: the opera- tion of a preference scheme, or approved public tender list, which would reduce industry and public sector cost associated with an all out open tender process at the same time supporting risk management; performance monitor- ing to enable the promotion of improved contractors and to ensure compliance where standards are violated; and; the targeting of resources to the emerging contractors which are demonstrating progress and the withdrawal of support from those which have graduated or have failed to progress [1]. Contractor grading in Swaziland is one of the tools that is used to regulate the constructio n sector. Unlike the Republic of South Africa where the contractor accredita- tion is done by an independent body, the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB), each department in the Ministry of Public Works and Transport done its own accreditation. The categories start from category 1 to 6 as illustrated on Table 1 for the roads department. Below the table shows the different categories. The small and medium size contractors in Swaziland fall between cate- gories 2 to 6. The tender price category is below R500, 000.00 and less than R20m. In addition to the contractors summarized in the table above, there are twelve (12) specialist contractors; with four (4) specializing in road marking, six (6) specializing in electrical works (streetlight maintenance) and two (2) specializing in premix road maintenance. As shown in the Table 2 below there are no foreign contractors under main category M1 and sub-category B, C and D. The table below clearly shows that the Building Contractors are dominated by Swazi people. Table 1. Civil contractor grading (roads department) in Swaziland Categories Local contractors Foreign contractors Project Category Eligible to tender for Category 1 1 2 Locally and internationally funded construction projects above E20 million. Category 2 1 2 Local and internationally funded construction projects above E10 million but below E20million. Category 3 4 0 Local and internationally funded construction projects above E5 million but below E10million. Category 4 6 0 Local and internationally funded construction projects above E1million but below E5million. Category 5 24 0 Local and internationally funded construction projects above E500, 000. 00 but below E3million. Category 6 158 0 Local and internationally funded construction projects below E500, 000. 00. Source: Ministry of public works and roads- Swaziland: 2007.  Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland 358 Table 2. Contractor grading (buildings department) in Sw aziland Categories Local contractors Foreign contractors Project Category Eligible to tender for Category M 8 5 Locally and internationally funded construction projects above E20 million. Category M1 6 0 Local and internationally funded construction projects above E10 million but below E20million. Category A 11 2 Local and internationally funded construction projects above E5 million but below E10million. Category B 13 0 Local and internationally funded construction projects above E1million but below E5million. Category C 20 0 Local and internationally funded construction projects above E500, 000. 00 but below E3million. Category D 91 0 Local and internationally funded construction projects below E500, 000. 00. Source: Ministry of public works and buildi ngs departm ent: 2007. 2.4.6 Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland The problems facing small contractors are not unique to Swaziland. The vast majority of construction firms are small enterprises that rely on outsourcing personnel as required. This has severely affected skills training and the retention of expertise in the industry as construction workers become highly mobile, walking in and ou t of the industry, depending on performance in other sectors of the economy. The impact can be seen in the rigid adher- ence to management techniques and construction prac- tices handed down from colonial times which, as a result of inadequate sk ills and capacity. 2.5 Research Methodology The paper used both primary and secondary data. Litera- ture review on small contractor s was conducted. A ques- tionnaire was designed with the help of the statistical Consultation Service (STATKON) of the University of Johannesburg. A field survey was carried out on 15 companies; the study target popu lation includes 100 con- tractors currently registered with the Ministry of Public Works and Transport Roads and Building sections. The Ministry of Public Works and Transport the Ministry of Public Works and Transport serves as a regulatory body for the construction industry in Swaziland. Swaziland is divided into four administrative regions; that are Hhohho, Manzini, Lubombo and Shiselweni. Data was collected between the 1st of June 2007 and 30th July 2007 and 87 respondents were interviewed. A total of one hundred (100) questionnaires were distributed to various contrac- tors registered under categories D, C, B (small) and A and M1 (medium) with the Ministry of Public Works and Transport Buildings Department contractor register and contractors registered under categories 6, 5, 4 (small) and 3 and 2 (medium) with the Ministry of Public Works and Transport Roads Department contractor register. Con- tractors registered under these categories are regarded as small and medium contractors, respectively. The ques- tionnaire was distributed to senior personnel including directors, project and construction managers. Out of the one hundred (100) questionnaires distributed, eighty- seven (87) were returned. Thirteen (13) questionnaires were not returned by the respondents. (See Figure 1) The Kingdom of Swaziland is a landlocked country surrounded by the Peoples’ Republic of Mozambique in the east and the Republic of South Africa’s Kwa Zulu- Natal Province in the south and the Republic of South Africa’s Mpumalanga Province in the west and in the north. The Kingdom of Swaziland has a population of around 1,128,814 inhabitants on 17,363 sq km of land. 3. Findings of Research 2009 The problems facing small contractors are not unique to Swaziland. The vast majority of construction firms are small enterprises that rely on outsourcing personnel as required. This has severely affected skills training and the retention of expertise in the industry as construction workers become highly mobile, walking in and ou t of the industry, depending on performance in other sectors of the economy. The impact can be seen in the rigid adher- ence to management techniques and construction prac- tices handed down from colonial times which, as a result of inadequate skills and capacity. Delays with interim and final payments, as well as onerous contract condi- tions faced by construction firms, can also impose huge constraints on the industry. Many construction firms have suffered financial ruin and bankruptcy because of delays in payment, which are common with government ontracts. Contemporary research that was conducted in c Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland 359 MAPUTO NELSPRUIT Moamba Namaacha Boane Manhica Bella Vista Marracuene Goba Ponta do Ouro Ressano Garcia Komatipoort Barberton White River Sabie Lydenburg Waterval Boven Amsterdam Piet Retief Wakkerstroom Vryheid Dundee Pongola Jozini Nongoma Louwsburg Hlobane Paulpietersburg Badplaas Ingwavuma MBABANE MANZINI SITEKI NHLANGANO Matsapha Lobamba Bhunya Piggs Peak Bulemb u Mhlume Simunye Sidvokodvo Big Bend Lavumisa Hlathikhulu Mankayane Mpaka Mafutseni Tshaneni Siphofaneni Nsoko Gege Sicunusa MPUMALANGA KWAZULU-NATAL MOZAMBIQUE SWAZILAND SOUTH AFRICA Lomahasha BP Mananga BP Matsamo BP Jeeps Reef Bulembu BP Josefsdal Ngwenya BP Oshoek Lundzi BP Wave rley Sandlane BP Nerston Sicunusa BP Emahlatini Gege BP Bothashoop Mahamb a BP Salitje BP Onverwacht Lavumisa BP Golela Mhlumeni BP Pongolapoort Dam Mnjoli Dam Sand River Reservoi r Maguga Dam Luphohlo Dam Vygeboom Dam Westoe Dam Jeric ho Dam Heyshope Dam Lake Sibaya Lake St. Lucia Lagoa Mandejene Lagoa Piti Lagoa Uembje Lagoa Chuali Ngwempisi Lusutfu Mbuluzi Mbuluzane Maputo Tembe Mbuluzi Komati Matilonge Pongolo Mkhondvo Ngwavuma Lusutfu Komati Crocodile Crocodile Komati Incomati Sabie Incom ati Sabie Seekoeispruit Usuru Ngwempisi Phongolo Phongolo Phongolo Mkuze Msunduzi Nyalazi Mlilwane N.R. Malolotja N.R. Songimvelo G.R. Mkhaya N.R. Mlawula N. R . Hlane N.P. Barberton N.R. Mawewe R.A. Kurger National Park Sterkspruit N.R. Maputo Elephant Reserve Tembe Elephant Reserve Ndumu G.R. Kosi Bay N.R. Mkuzi G.R. Pongolapoort N.R. Sodwana Bay N.P. Itala N.R. Hluhluwe G.R. Phinda Resource Reserve The Greater St. Lucia Wetland Park EN 2 EN 5 EN 4EN 1 MR 1 MR 1 MR 2 MR 3 MR 3 MR 3 MR 3 MR 4 MR 4 MR 5 MR 5 MR 6 MR 7 MR 8 MR 8 MR 8 MR 9 MR 9 MR 10 MR 10 MR 11 MR 11MR 11 MR 12 MR 13 MR 14 MR 14 MR 14 MR 15 MR 16 MR 18 MR 19 MR 19 MR 20 MR 21 MR 21 MR 24 MR 25 Figure 1. General survey offices, ministry of natural resources, Swaziland, 2009 2007 by the authors revealed the current reasons for the failure of small and medium size contractors in Swazi- land. 87 owners of the small and medium size contractors were interviewed. 68% of the contractors are less than four years; 20% are between 5 and 9 years; and 12 % had operated for more than 10 years. There was no contractor that had operated more than 15 years. 63% of the re- spondents believ e that the four major bank s in Swaziland have proper systems in place to support small and me- dium size contractors once they have secured work. On the other hand 37% of the respondents do not believe that the four major banks in Swaziland have proper systems in place to support small and medium size contractors. 33.4% of the respondents think that the current environ- ment within the construction industry in Swaziland is favorable for small and medium size contractors to be successful. On the other hand 66.6% of the respondents believe that the construction industry environment is not Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland 360 41% 17% 35% 5% 2% None at all Very poor poor adequately Very well 36% 3% 34% 22% 5% None at all Very poor Poor Adequate l y Very Well Figure 2. Develop business skills Figure 3. Develop management skills favorable for the success of the small and medium size contractors. From the ab ove figure 40% of th e respondents are sat- isfied with business skill development and 60% of the respondents were not satisfied. The figure above shows that the respondents are not satisfied with regard to the development of business skills. (See Figure 2) From the ab ove figure 27% of th e respondents are sat- isfied with the development of managerial skills. 73% of the respondents ar e not satisfied with th e development of managerial skills. It is clear from the above figure that respondents had n ot been trained. (See F igure 3) From the figure below 47% of the respondents are sat- isfied with the development of technical skills. 53% of the respondents ar e not satisfied with th e development of technical skills. (See Figure 4) From the research conducted it can be concluded that the relative lack of success among the small and medium size contractors in Swaziland is a results of the following problems which must be addressed in order for the con- tractors to be successful: A lack of resources for either large or complex construction work. An inability to provide securities, raise insur- ance and obtain professional indemnity. 36% 3% 11% 44% 6% None at all Very po o r Poor Adequately Very well Figure 4. Develop technical skills The contracts were inevitably packaged in such a way as to exclude small contractors. Inadequacy in technical and managerial skills required in project implementation. Lack of continuity in relation to type, scale and location of work An inadequate approach and insufficient know- ledge, time and experience required for the whole proc- ess of finding work, once foun d, insufficient understand- ing of the contract documentation and the preparation and submission of tenders. Slow and non-payment by government after co- mpleting a government project Little or inadequate effort has been made to id e- ntify the causes of failure among the local contractors in the implementation of construction projects in Swazi- land. The need for the introduction of a set of rules to govern the construction industry done by an independent body in the Kingdom of Swaziland. 4. Lessons and Recommendations The literatures that have been reviewed both in Swazi- land and internationally demonstrated that the develop- ment of Swazi contractors, small and medium sized con- tractors faced several challenges which must be ad- dressed. In the case of Swaziland the majority of the re- spondents are dissatisfied with the quality of assistance offered by the government to the small and medium sized contractors in Swaziland. Small enterprises contribute positively to the eco nomics of the country and to the sur- vival of large numbers of people. However, the success of small enterprise is impaired by the common weakness from which many enterprises suffer. A vibrant self-sus- taining construction industry is one that is planned and matched with government capital programmes and sup- port schemes aimed at improving the efficiency of the local construction industry. Swaziland is faced with a large challenge of developing infrastructure in the disad- vantaged communities, and also upgrading the existing Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Problems Facing Small and Medium Size Contractors in Swaziland361 infrastructure to cope with the high demand. It is rec- ommended that the Swaziland Government must under- take the following measures to address the challenges facing Small and Medium Size contractors: Business skills: training in business manageme- nt skills is key the in managing a construction business effectively and efficiently. Management skills: financial management sho- uld be emphasized as well as networking with other peo- ple with similar businesses Good record keeping: financial records should be prioritized and a record of books of accounts on a daily, weekly, monthly and annual basis should be estab- lished. Well managed cash flow: prepare cash flow forecasts and budgets and prepare a cost-benefit analysis. The government should break down big contr- acts into small contracts so that small contractors with lower grading can qua l i f y to do the job The government should assist in training Small and Medium Size contractors on business management The government should create a construction advice centre The government should establish a Contractor Training Institute to train Small and Medium Size con- tractors Government payment system must be improved Government must establish financial institutions that will act as guarantees in order to enable contractors to have access to finance. 5. Conclusions The literatures that have been reviewed both in Swazi- land and internationally demonstrated that the develop- ment of Swazi owned contractors, small and medium sized contractors, in particular are face many challenges which need to be addressed in order for the contractors to sustainable in their growth. The majority of the respon- dents are dissatisfied with the quality of assistance of- fered by the government to the small and medium sized contractors in Swaziland. The problem lies, however, in the formation of a construction industry in line with the implementation of government programmes that must facilitate the creation of a vibrant self-sustaining con- struction industry. A vibrant self-sustaining construction industry is one that is planned and matched with gov- ernment capital programmes and support schemes aimed at improving the efficiency of the local construction in- dustry. The study finds that lack of effective management during their early stages is a major cause of business failure for small and medium sized contractors. Owners tend to manage their businesses themselves as a measure of reducing operatio nal costs. Poor reco rd keeping is also a cause for start-up business failure. Lack of financial management; lack of entrepreneurial skills; lack of pro- per training; lack of resources; lack of technical skills, lack of contractual and managerial skills; late payment for work done which are common with government con- tracts; inability to get credit from suppliers and fronting for established contractors are also contributing factors for the failure of small contractors in Swaziland. 6. Acknowledgements Research works in this paper are partial supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the University of Johannesburg Research Funding. REFERENCES [1] Ministry of Public Works and Roads, “Swaziland. Swazi- land today,” 2007, http://www.gov.sz. [2] Construction Industry Development Board, “South Africa construction industry status report – Synthesis review on the South African construction industry and its develop- ment. Discussion document,” South Africa, 2004. [3] National Advisory Council on Innovation, “The potential impact of skills shortages on the innovative capacity of major capital engineering projects,” National Advisory Council on Innovation and Department of Science and Technology, Pretoria, 2003. [4] Construction Industry Development Board, Department of Public Works, Construction Education and Training Authority, “Towards a common framework for enterprise growth and sustainability,” Sustainable contractor devel- opment, National Workshop, Pretoria, 2005. [5] A. Kesper, “Failing or not aiming to grow? Manufactur- ing SMMEs and their contribution to employment growth in South Africa,” TIPS Working Paper 15, 2000. [6] D. Matas, “Towards the new millennium series: No more: The battle against human rights,” Ottawa, Dundurn Press, 1996. [7] Statistics South Africa, “Labour force survey for septem- ber 2005,” Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, 2005. [8] M. K. Nissanke, “Financing enterprise development in sub-Saharan Africa,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 25, pp. 343–367, 2001. [9] C. M. Rogerson, “Unpacking tourism SMMEs in South Africa: Structure, support needs and policy response,” Development Southern Africa, Vol. 22, pp. 623–642, 2005. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM |