Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

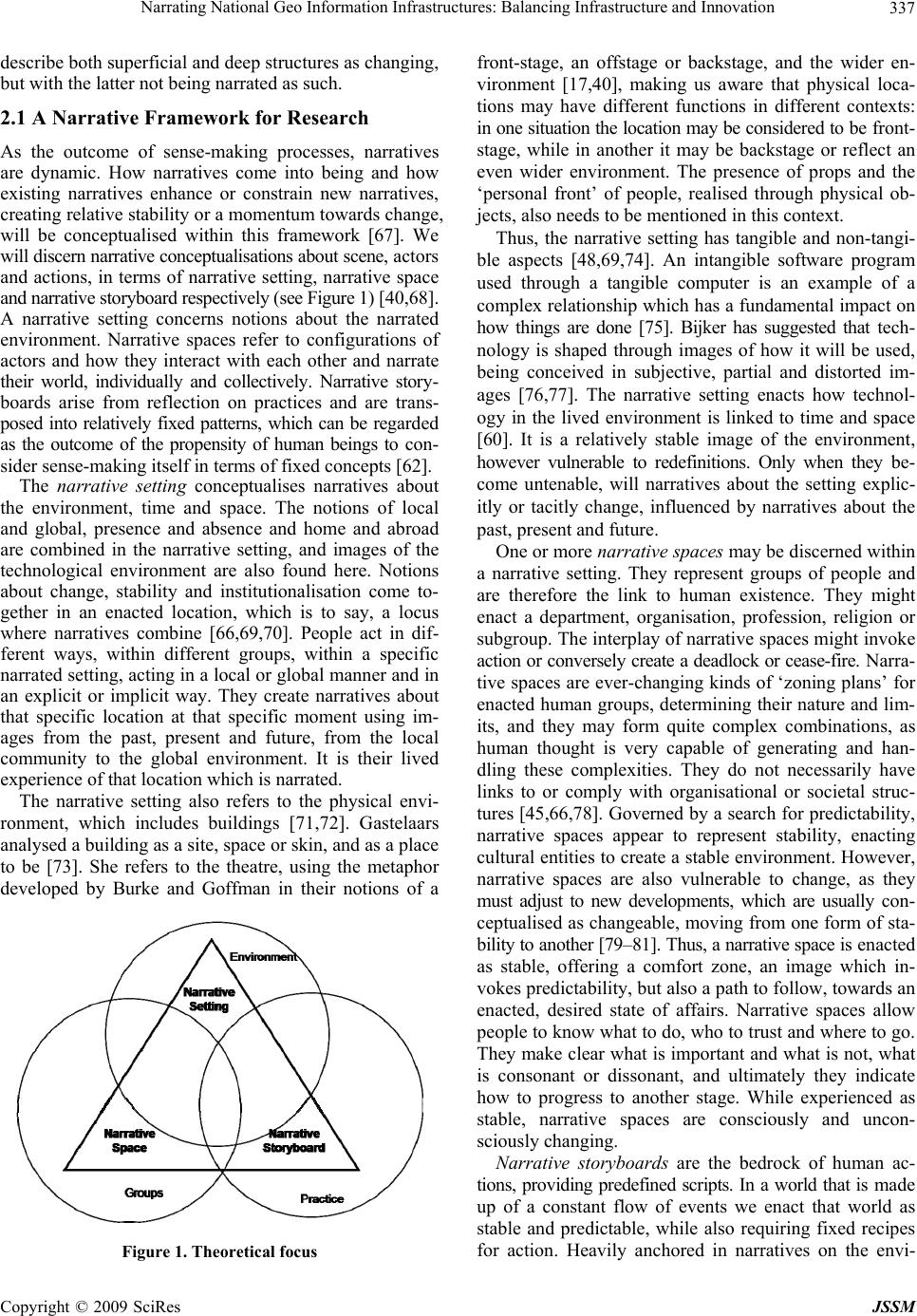

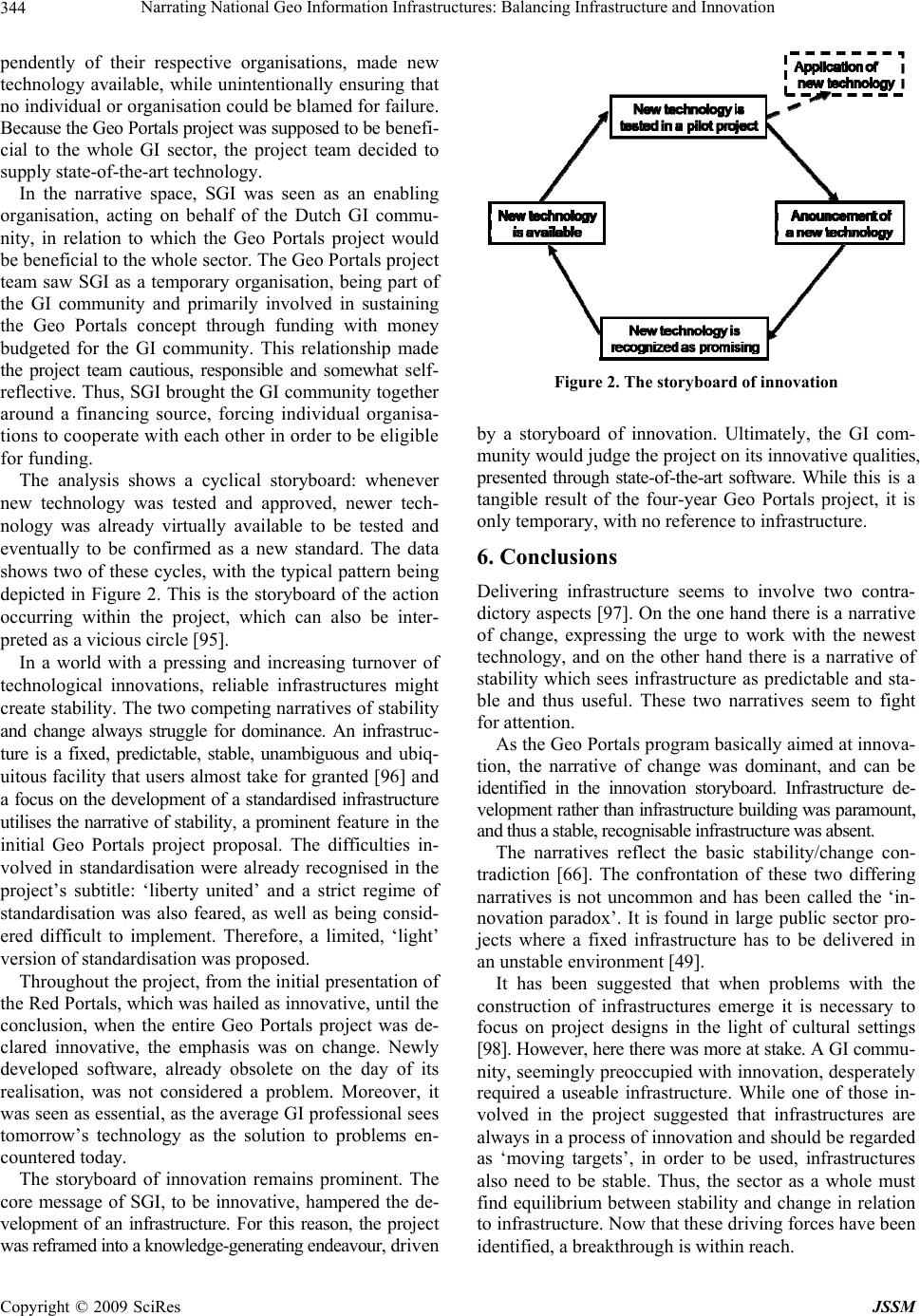

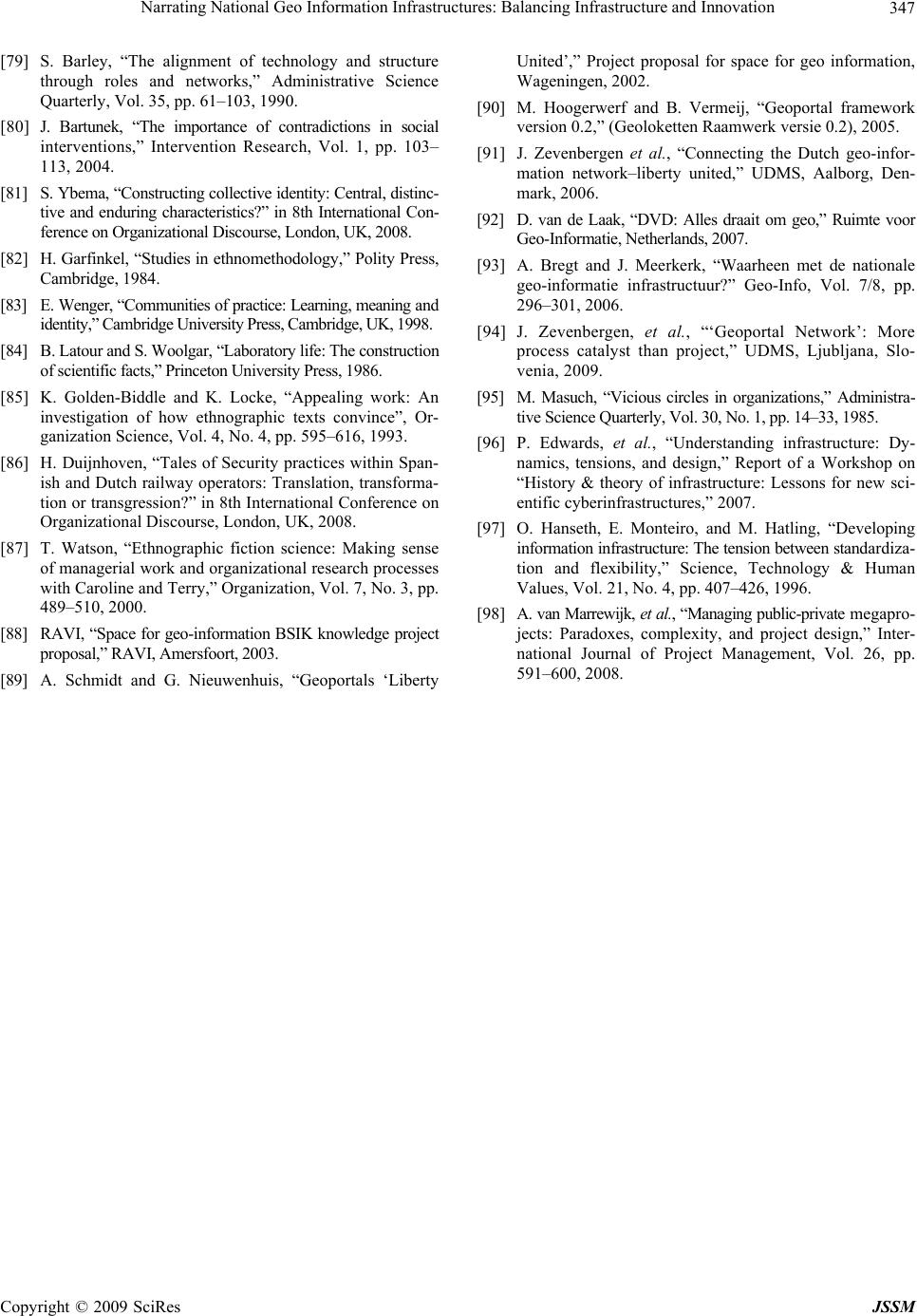

J. Service Science & Management, 2009, 2: 334-347 doi:10.4236/jssm.2009.24040 Published Online December 2009 (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM Narrating National Geo Information Infrast r u c t u res: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation Henk Koerten1, Marcel Veenswijk2 1Department of Delft University of Technology, Amsterdam, Netherlands; 2Department of Culture, Organization and Management, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Email: h.koerten@tudelft.nl, m.veenswijk@fsw.vu.nl Received September 10, 2009; revised October 16, 2009; accepted November 18, 2009. ABSTRACT This paper examines narratives relating to the development of National Geo Information In frastructures (NGII) in eth- nographic research on a Dutch NGII project which was monitored throughout its course. We used an approach which focuses on narratives concerning the environment, groups and practice to elicit sense-making processes. We assert that narratives are relatively fixed and that they only change under specific circumstances. Moreover, the fixing of or change in narratives takes place in practice, so our research approach aimed at analysing narratives of practice, which we label ‘storyboards’. For this purpose, project meetings and conferences were observed, key persons both within and outside the project environment were interviewed, and an analysis of relevant documents and video footage was under- taken. Storyboards are created by actors as a result of day-to-day challenges related to project goals, technology and infrastructure. In our research we found that these storyboards occur as vicious circles from which actors cannot es- cape. In the specific case analysed, our interpretation of the narrative storyboards suggested that these vicious circles are caused by the ina bility of project participants to distinguish between infra structure and innovation requiremen ts in their daily work. Keywords: Narrative Analysis, Narrative Approach, Innovation, Organisation, NGII, Infrastructure 1. Introduction There is a worldwide tendency to create facilities on a national scale to collect and disseminate location-based information, usually called geo information [1]. Car naviga- tion systems are a form of geo information used by the general public, and geo information is also applied in government and business organisations to make them m or e effective. Within organisations, this information is often managed by a Geographical Information System (GIS), and between organisations, through National Geo Infor- mation Infrastructures (NGIIs) with national governments playing a key role in their dissemination [2–5]. When setting up a program aimed at establishing N GII s, policy advisors take organisational aspects seriously, but do not treat them as manageable phenomena [6,7]. Tech- nical aspects are regarded as crucial [3], and those in- volved in implementing the programs generally seem to overlook the organisational consequences, denying the relationship between organisational change and NGII implementation [8]. Therefore, organisational structures, modes of cooperation and work relationships have not been topics of interest in the context of research into NGII implementation [9]. However, while technological developments are still regarded as crucial, those invo lved in implementation are now more inclined to take the organisational aspects of NGII development into account, culminating in design rules borrowed from political science, economics and management science [10–12]. Practitioners still point to difficulties with infrastructure development–mostly in the context of specific projects–of which we still have little knowledge of the lived experience of the project members [13,14]. Our aim is to find out why people who have problems in their daily work nevertheless maintain their current practices and refrain from looking for alternative meth- ods. In relation to NGII development, there is a tendency to continue developing design rules while rarely taking the implementation processes into account. Our focus is practical: on how NGIIs are discussed in meetings, inter- views and policy documents, where these discussions cul- minate in the creation of narratives. The research ques- tion guiding this paper is: How can we understand NGII  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 335 implementation using narrative analysis? Our secondary questions are: How do technological and organisational aspects interact with each other? How are goals and re- sults perceived? And do these goals and results change over the course of the project? Using a narrative approach, this paper provides an in- depth ethnographic case study of a Dutch NGII imple- mentation project called Geo Portals. The project was intended to realise a part of the Dutch NGII by disclosing governmental geo information in a thematically organised way. Our research findings demonstrate that the initial project goal of building an infrastructure gradua lly c h a n ge d over the course of the project, moving towards knowl- edge creation to facilitate innova tion aimed at the further development of the NGII. We will start with a description of the theoretical as- sumptions underlying the narrative analysis approach to research, followed by an account of the research meth- odology. An analysis of th e project in terms of the theory will follow, and finally, we will provide a summary and some concluding remarks. 2. The Narrative Analysis Approach to Research Symbolic interactionism introduced the idea that human thought is shaped by social interaction, and treated the modification of meanings and symbols as a process [15]. Goffman expanded this notion by adding the ability of human beings to look at themselves from another point of view [16], framing the notion using the theatrical terms of a ‘front-stage’ and a ‘back-stage’ [17]. Over his career, Goff- man became aware of the ritualistic and institutionalising aspects of social interaction, but failed to specify how and why these frames or structures emerge [18–20]. Sociologists have attempted to understand society by gaining insight into how the structures involved in the process of modernisation affect our lives [21–24]. Some have made efforts to integrate micro and macro ap- proaches [25–27]. For example, Bourdieu implicitly re- jected the assumption of an objective truth, implying that structures are socially constructed, and he attempted to take a middle position which he labelled both ‘construc- tivist structuralism’ and ‘structuralist constructivism’ [27 ,2 8] . Bourdieu conceptualised habitus as the cognitive structures through which people deal with the social world, being both individual and collective, dialectically developed and internalised, a process which he labelled ‘practice’. A ‘field’ was conceptualised as a network of relations among objective positions and not as a network of inter- actions or inter-subjective ties among individuals. These relationships, regarded as ex isting externally with respect to individuals, determined the position of individual agents through their acquisition of various kinds of capi- tal: economic, cultural (knowledge), social (rela tionships) and symbolic (prestige). In this process, field and habitus define each other in a dialectical relationship. Bourdieu and Goffman may have different points of departure, but there are similarities in their conceptuali- sations. Goffman’s dramaturgical perspective may, to a considerable extent, be comparable to Bourdieu’s habitus, while Goffman’s notion of frames resembles Bourdieu’s field concept and practice is more or less interchangeable with Goffman’s concept of the ‘front-stage’. While this comparison may appear to be a broad generalisation, thes e observations will prove useful in blending the two ap- proaches together into one theoretical concept for re- search. Nevertheless, while an intersectional framework such as this might provide useful notions about the life world affecting individual, group and inter-group behav- iour, the very aspect of meaning creation remains unad- dressed. It remains unclear how images come to life and develop over time, as this framework assumes univocal- ity, iniquitousness and fully informed actors and as such the ambivalence, ambiguity and incompleteness of world- views is overlooked. Thus, the theoretical notions presented above provide useful hints for a theoretical approach but do not address the process of sense-making needed to answer the re- search question. Therefore, we will focus on the inter- pretation of lived experience as a guide for action and extend this towards a narrativ e approach using linguistic, anthropological and social psychological insights [29–31]. Interpretation, meaning creation and sense-making have become guiding concepts in the development of less positivistic methods [32,33]. Two sources that have in- spired narrative theory may be distinguished: a ‘linguistic turn’, inspired by Saussure, Wittgenstein, Chomsky and Derrida, and a ‘narrative turn’, with more emphasis on stories and meaning, represented by authors such as Barthes, Bakhtin, Boje, and Gabriel [34]. In itself, language has no relationship to time or the originator of an utterance [3 5]. The concep t of discourse, however, is treated as a combination of spoken word and written text, linked to time and space and used to make sense of the world, without drawing a distinction between the two [36]. In relation to the concept of discourse, the process of enactment is conceived of as communication through written and spoken symbols, usually linguistic. For example, to complete a management task, people write, read, speak, listen and discuss, using messages which convey myths, sagas, results, setbacks, challenges or strategies [37]. While language has been recognised as the dominant vehicle for the development of meaning in the discursive approach, the dynamic character of organisational prac- tice has invoked interest in linguistic aspects other than text alone, such as metaphor, st ories, novels, rituals, rhetoric, language games, drama, conversations, emotions and sense- making [38]. Grounded in literary criticism, new meth- ods of analysis have emerged and been labelled as the narrative turn, which is aimed at delineating stories and storylines rather than texts [39–42]. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 336 Meaning is created, maintained, altered and destroyed and may be used to contemplate, to manipulate, be pur- poseful and invoke change [43–47]. The narrative turn has been considered fundamental in interpretive organ- isational research for conceptualising the notion of or- ganisation in a more dynamic way (Hatch and Yanow, 2003). These dynamics have been envisioned in terms of people using and producing frames of reference in a cy- clical process of enactment-selection-retention [48], as a dialectical process moving towards objectification [28], or as a narrative that is edited under particular circum- stances [31,49]. The concept of narrative is broad, in the sense that it can be regarded as structuring human mem- ory, and therefore should be conceptualised as both me- dium and process [50]. The concept of discourse, how- ever, is more defined, referring to meaning produced in the exchange of signs and symbols, and in this respect more closely related to symbolic interactionism [50,51]. Narrative has been regarded as story [42], as telling a story [38] and as the art of telling a story [52], while there are also other approaches concerned with linking stories and narratives [49,53–55]. Living in a world composed of stories, we use narratives for communica- tion and to give meaning to experience [42]. In providing an account of events, narratives allow us to create an interpretation of these events, relating the story in a fa- vourable manner. Some stories are created for single use, while others are retold and altered and in the process gain a meaning they would never have had if they had been told only once. In this way they become a frame of ref- erence for future stories and actions [56]. Once stories begin to have a life of their own, they grow further to become narratives which might be only loosely or even poorly connected to the original [55]. They become uni- versal images, constituting all aspects of society, refer- ring to the culture of all kinds of people, culminating in identity-creation using social categories [57]. From a manager to a company car, human and non-human iden- tities are created by storytelling, leading to narratives that are continuously constructed and therefore subject to change. Having a plot does not imply that narratives are always visible and recognisable, they can be prominent or latent, and can also sometimes be unconsciously pre- sent to actors. They are an interpretation of assembled, either real or imagined stories, which Boje, after Clair, called ‘narratives dressed as theories’ [55]. The hermeneutic approach implies that a specific nar- rative can only be understood when it is interpreted in relation to other narratives, for example if we conceptu- alise narration as a ‘grand narrative’ grounded in many ‘micro stories’ which are mutually dependent [49,55]. This notion is reminiscent of the sociological micro- macro debate which links Bourdieu to the insights presented above. To avoid being confined to a type of hierarchically lay- ered concept, one can focus on th e morphology of narra- tives over time, conceptualising how such narratives are edited by the actors involved so as to invo ke th e narrative, as well as sustain or to change it [31,49]. However, be- cause the editing process is associated with the particular editors, there is a danger of overemphasising the role of individuals and in so doing implicitly sustain the idea of ‘culture creation’ or ‘cultural intervention’, which we hav e seen before [43,58]. The notion of narrative has also been distinguished by declaring everything before narrative to be ‘ante-narra- tive’. Verduijn refers to ante-narrative as ‘lived experi- ence’, which she finds to be speculative, multifaceted and ambiguous, and while it always tends towards a co- herent story, it is always prior to its reificatio n into a sen- sible narrative [30,34,55]. However, while this distinc- tion may be tempting, it is difficult to sustain the division between narrative and ante-narrative. This approach also presupposes that all the storylines–the ‘Tamara of sto- ries’–can be known by the researcher [30]. However, it is impossible to grasp the full picture, just as it is impossi- ble to simultaneously be in all places at all times. None- theless, people still look for a clear, overall picture to give sense to their experiences, and therefore missing elements are filled in and the incomplete picture is supplemented with fantasies that function as experiences and thus con- struct the full picture [35,50]. Thus, the development of meaning requires an overall understanding of the relevant situation, in terms of both ante-narrative and narrative. As humans, we can only understand change with great difficulty, we notice when something has changed only after a certain period of time has elapsed and we perceive this as an interval [59]. As a result, change is reduced to a series of instances: the difference between one state of affairs a n d anothe r gives us clues a b out cha n ge, dete rmining our thinking about time in a profound way [ 60 ,6 1] . D ue t o modernity dictating a linear concept of time, we tend to experience that as ‘concrete lived time’ [62], and while change is basic to life, it is difficult for humanity to grasp it. In this sense, we are ‘becoming’ instead of ‘being’ [60,63,64]. The concept of becoming elicits the sen se we make of change. Sense-making, or meaning creation, can be envisioned as a human attempt to comprehend change, in a process in which we attempt to convert an influx of stimuli into adequate concepts [62]. However, striving for fixed concepts in the process of sense-making means that intentional shifts in meaning rarely occur because of the tendency to maintain familiar concepts. Despite this tendency, meaning does change–usually without the aware- ness of the meaning creator–due to the changing environ- ment. The propensity to ignore change by creating stable narratives is prevented by these changing circumstances, giving change the quality of ‘basic assumption’ or a ‘deep structure’ [65], or of basic, dichotomous, generally sub- conscious human preferences [66]. For Schein, the more superficial cultural notions are, the more they are sub ject to change, in which case perhaps it would be better to Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 337 describe both superficial and deep structures as changing, but with the latter not being narrated as such. 2.1 A Narrative Framework for Research As the outcome of sense-making processes, narratives are dynamic. How narratives come into being and how existing narratives enhance or constrain new narratives, creating relative stability or a momentum towards ch ange, will be conceptualised within this framework [67]. We will discern n arra tive con ceptualis ations about scen e, ac t or s and actions, in terms of narrative setting, narrative space and narrative storyboard respectively (see Figure 1) [40,68]. A narrative setting concerns notions about the narrated environment. Narrative spaces refer to configurations of actors and how they interact with each other and narrate their world, individually and collectively. Narrative story- boards arise from reflection on practices and are trans- posed into relatively fixed patterns, which can be regarded as the outcome of the propensity of human beings to con- sider sense-making itself in terms of fixed concepts [62]. The narrative setting conceptualises narratives about the environment, time and space. The notions of local and global, presence and absence and home and abroad are combined in the narrative setting, and images of the technological environment are also found here. Notions about change, stability and institutionalisation come to- gether in an enacted location, which is to say, a locus where narratives combine [66,69,70]. People act in dif- ferent ways, within different groups, within a specific narrated setting, acting in a local or global manner and in an explicit or implicit way. They create narratives about that specific location at that specific moment using im- ages from the past, present and future, from the local community to the global environment. It is their lived experience of that location which is narrated. The narrative setting also refers to the physical envi- ronment, which includes buildings [71,72]. Gastelaars analysed a building as a site, space or skin, and as a place to be [73]. She refers to the theatre, using the metaphor developed by Burke and Goffman in their notions of a Figure 1. Theoretical focus front-stage, an offstage or backstage, and the wider en- vironment [17,40], making us aware that physical loca- tions may have different functions in different contexts: in one situation the location may be considered to be f r on t- stage, while in another it may be backstage or reflect an even wider environment. The presence of props and the ‘personal front’ of people, realised through physical ob- jects, also needs to be mentioned in th is context. Thus, the narrative setting has tangible and non-tangi- ble aspects [48,69,74]. An intangible software program used through a tangible computer is an example of a complex relationship which has a fundamental impact on how things are done [75]. Bijker has suggested that tech- nology is shaped through images of how it will be used, being conceived in subjective, partial and distorted im- ages [76,77]. The narrative setting enacts how technol- ogy in the lived environment is linked to time and space [60]. It is a relatively stable image of the environment, however vulnerable to redefinitions. Only when they be- come untenable, will narratives about the setting explic- itly or tacitly change, influenced by narratives about the past, present and future. One or more narrative spaces may be discerned within a narrative setting. They represent groups of people and are therefore the link to human existence. They might enact a department, organisation, profession, religion or subgroup. The interplay of narrative spaces might invoke action or conversely create a deadlock or cease-f ire. Na rr a- tive spaces are ever-changing kinds of ‘zoning plans’ for enacted human groups, determinin g their nature and lim- its, and they may form quite complex combinations, as human thought is very capable of generating and han- dling these complexities. They do not necessarily have links to or comply with organisational or societal struc- tures [45,66,78]. Governed by a search for predictability, narrative spaces appear to represent stability, enacting cultural entities to create a stable environment. However, narrative spaces are also vulnerable to change, as they must adjust to new developments, which are usually con- ceptualised as changeable, moving from one form of sta- bility to another [79–81 ]. Thus, a narrative space is e n a ct e d as stable, offering a comfort zone, an image which in- vokes predictability, b ut also a path to follow, towards an enacted, desired state of affairs. Narrative spaces allow people to know wh at to do, who to trust and where to g o. They make clear what is important and what is not, wh at is consonant or dissonant, and ultimately they indicate how to progress to another stage. While experienced as stable, narrative spaces are consciously and uncon- sciously changing. Narrative storyboards are the bedrock of human ac- tions, providing predefined scripts. In a world that is made up of a constant flow of events we enact that world as stable and predictable, while also requiring fixed recipes for action. Heavily anchored in narratives on the envi- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 338 ronment and social groups, they are also based on past and future actions [28,48,59]. People adhere to certain unwritten rules in daily life, allowing them to present themselves as good citizens, and thus feel uncomfortable when the rules are not appropriately applied [82]. Story- boards provide us with a narrative of how to move from an initial state of affairs towards a new state within a par- ticular context. They may relate to action that still needs to take place, that which is being undergone, or that w hic h has already taken place, linking the action in question to time and space and thereby delimiting the storyboard’s explanatory power. In this way a plot of the action is provided and related to the circumstances con ceptualised in narrative settings and narrative spaces [17]. Storyboards emerge in relation to groups of people, who can be considered as apprentices becoming accustomed to a general way of doing something [83]. The people wi thi n such a group may feel confined in relation to a specific array of actions which have been proposed as a means to move from chaos to order [84]. Predictions concerning actions and outcomes are made because these allow peo- ple to know what to expect and to determine which stories are dominant and how they form a logical sequence [53]. The narrative storyboard makes us aware of the limited ways of creating a plot. It reveals how a specific story- board connects to the setting and spaces of its constitu- tive narrative and what aspects of the narratives are spe- cific to that storyboard. Their predictable features make th em triggers for change. In this way, while the exact prediction of narrative progression is impossible, the narrative provides building blocks for the analysis of change, shedding light on how narrative change can be mapped [30]. 3. Methods This section will provide some information on the con- text of the Geo Portals project, as well as an explanation of the ethnographic research design. 3.1 Context In early 2005, the Na tional Initiative for Innovation S ti mu- lation (BSIK) began the Space for Geo Information pro- gram (SGI) (Ruimte voor Geoinformatie). The project ran until the end of 2008, with a budget of 58 million euros. The SGI program was set up to provide grants to projects dealing with geo information and thereby stimu- late innovation and promote the realisation of the Dutch National Geo Information Infrastructure (NGII). The Geo Portals project emerged from the initial discussions on the content and design of the SGI program, bringing to- gether thirteen governmental and non-governmental or- ganisations in the field of geo information who proposed the establishment of a network of geo portals for the dis- closure of geo data. The Geo Portals project had a two million Eu ro budget, with 60 p ercent of its fund ing com- ing from the SGI initiative, while the participating or- ganisations were to supply the remaining 40 percent. Within the Geo Portals project, geo data was regarded as a crude product that should be thematically disclosed in order to obtain geo information from which society as a whole could benefit. In relation to the multifaceted palette of the SGI pro- gram, Geo Portals was one of the larger projects, and was often described as a prestigious, key project by program officials. The projects that were set up were evaluated in terms of their ability to bring the Dutch NGII closer to completion. In this context, Geo Portals was focused on the overarching goal of the program: disclosing geo data from di ff er ent source s to prod uc e ge o inform ation. 3.2 Research Design In the next section, we will present ethnography of the Geo Portals project, which ran from the beginning of 2005 until the end of 2008. It will become clear that nar- ratives referring to the project changed during its pro- gression. However, before turning to the case description we will explain the ethnographic design of our research. One researcher monitored the project during its course. Because social scientific research on how the project was conducted was one of the project goals, the researcher was accepted as a full member of the project committee, which consisted of one representative from every partici- pating organisation. Monthly meetings were scheduled with the intention of addressing management issues and, especially at the outset, serving as a platform for devel- oping the scope of the project. Workshops open to and aimed at professionals within the geo information sector were also organised with the purpose of project promo- tion. Two brainstorming sessions were held by the project team in the first phase of the project, intending to estab- lish a clear and univocal project approach agreed on by the project committee. These events were observed and also interviews were conducted with key persons, both during the commencement and conclusion phases of the project. Relevant documents and some video footage were also analysed. In additio n, the researchers observed the presentations of the project at the geo information conferences, as well as the subsequent audience reactions. Ethnographers have to be convincingly authentic (‘been there’), plausible (relevant to the reader) and engage in critical analysis [85]. In order to do so, this research pro- ject followed writing conventions developed by Watson and extended by Duijnhoven concerning the transfer of field notes into convincing and authentic texts [86,87]. To meet these requirements, we will present excerpts from our interviews and field notes. In order to summa- rise the numerous discussions occurring during meetings, these have been condensed into a representation of the typical form of the discussion concerning a particular Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 339 I remember how Geo Portals emerged. The idea behind broking and bargaining events organised by SGI was that through discussion among representatives of geo infor- mation organisations, ideas for concrete projects would pop up. During one of those meetings, the Geo Portals concept just came out of a plenary discussion. Then the moderator asked which organisations were willing to par- ticipate. Representatives of interested organisations raised their hands, as did I. So, all of a sudden I was an initiat- ing member of an instantly formed club of enthusiastic peo- ple who wanted to disclose geo information through portals. topic. These representations of conversations are in essen c e fictitious; however, they are based on conversations re- corded in field notes and, to a lesser extent, in interviews. The research materials revealed the presence of narra- tives that developed over time. They were in continuous flux and either prominent or concealed, close or distant. The narratives within the project not only show how pro- jects function as arenas where the narrative of change is created, contested, appropriated and diffused, but also how the quest for project narratives among members may serv e both to reduce as well as to increase ambiguity. On the one hand, the project narratives seem to reduce ambigu- ity by providing a ‘narrative of change’ in terms of the use of new software applications. On the other hand, these software applications fail to offer a solution be- cause they create a new ambiguous situation, requiring another ‘narrative of change’. Coping strategies are de- veloped through the redefinition of the initial project goals, aligning them to these narratives of change. 4. Analysis In this section we provide a detailed description of three phases of the Geo Portals project. Each is described sepa- rately and followed by a narrative an alysis that identifies the narrative setting, space and storyboard. 4.1 Getting Started The SGI program started in 2002, with the basic idea of stimulating innovation in order to boost geo information sharing. The next step was to bring together representa- tives of organisations in the GI field to make goals more concrete. The result was a glossy brochure, with a pro- gram outline produced by a con sortium of 10 universities, 20 research institutes, 60 companies, 40 governmental bodies and 30 geo information producers [88]. It was ar- gued that government needed complex information about a complex society to develop convincing policies. To m a ke the information manageable, it was to be ordered spatially as geo information, disclosed by a National Geo Informa- tion Infrastructure (NGII). The bottom line was to make geo information av ailable in a structur ed manner, with it bein g disseminated independent ly by indi vidual organi sati ons. To promote future projects, SGI organised ‘broking and bargaining days’ on which representatives of orga nis atio ns from the GI sector were invited to generate project ideas. It was in this context that the concept of Geo Portals emerged. Some typical observations of those in atten- dance were as follows: SGI mobilised the field. They organised broking and bargaining days in order to get rough ideas. Some 25 ideas were identified as potentially successful. In the end, these ideas were connected to organisations; it was just one big dating show. It became obvious that some central portal facility was needed and that our organisation should play a role in its development. That the overarching concept of Geo Portals should be liberty united, was obvious from the outset. A central, top- down organisation was totally out of the question. Th e i d e a was a network of portals of different nature, working together with a mini mum set of rules. Those involved in the discussion saw the rudimentary concept of Geo Portals as a collective idea in need of de- velopment. The thirty organisations willing to participate were gradually reduced to thirteen, and in October 2002, representatives from these organisations presented an initial proposal which envisioned thematically catego- rised, colour-coded portals lik e red for built environment, green for nature and agriculture, and brown for sub- surface conditions [89]. After the initial submission in 2002, a rewriting proc- ess occurred, giving the project more focus. In the min- utes of early project meetings, there are clear conceptions about how data should be distributed. It was stated that all the processes for disclosure, search, diffusion and pay- ment should be web-based, while how all the different data sources were to be connected was not a matter of discussion. The first rudimentary description of the geo portal framework presented a static image: the portal wo u l d be based on proven technology and standards and also on a fixed notion of architectur e [90]. While the project goals were stated clearly and unam- biguously, at their regular meetings the representatives of the participating organisations expressed doubts about ho w to proceed. They were uncertain about the financing and procedures for reporting to SGI, but even more about the essence of the project. Now the project was about to start, the representatives felt the need for definitions about what a portal should look like, how users would be reached and what technology would be used in its setup. A typical discussion in a meeting of representatives would proceed as follows: A: If we want to set up a proper Geo Portals, we need to be clear about standards. It is obvious that we use the most recent and commonly used standards. We are not going to use any standard that has not been accepted by the community, or that has not proved to be useful. B: I agree on that. If nobody objects, we should pro- ceed to the next topic, and that is user orientation. We have to be demand-driven, preventing us from making the same mistakes they made in the NCGI project. So how can we be demand- driven? Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 340 C: First and foremost we need to disclose our data in a way that it can be readily found. Furthermore, we need to present it in a format that can be read by the user. So, we need to use the proper standards. B: I agree. We need to use proper standards, those that are widely accepted. A: Now we agreed on how to settle the standards issue, we are discussing standards again. The motto of Geo Portals was ‘liberty united’, which reflected the fact that it was a network of portals estab- lished by various organisations, each with its own auton- omy, but working according to a minimal set of rules. In defending this view of the essence of Geo Portals, it was often explained as a reaction to a former national project regarding geo information, the National Clearinghouse for Geo Information (NCGI). The feeling was that NCGI had failed due to the central, top-down enforcement of de- tailed standards and work procedures and this had proved to Geo Portal protagonists that organisations were not in- clined to comply voluntarily with strict rules. To avoid another failure, they decided to meet as a small group of motivated organisations connected through a minimal num- ber of mutually agreed standard s. While Geo Portals was sketched out in organisational terms, discussions on how to proceed would always come down to technical matters. Standardisation was consid- ered to be crucial, followed by the question of whether the data was accessible enough. The bottom line was that it was most important that the issue of technological standardisation should be settled properly. Technological matters dominated discussions: A: Technology is not really a problem anymore. We can build everything we want without any limit. All the techniques needed are at our disposal. B: That’s right, the things that do matter are organisa- tional aspects. Look at the US example of Geospatial One Stop. They just do it: American government agen- cies put everything they have on the web, without restric- tions. C: But its quality is doubtful at best, they don’t guar- antee its accuracy. I wonder if anybody actually uses it. A: If we follow the example of Geospatial One Stop, then it will look li ke NCGI. We have to do better t han that. B: Just use the right standards. That is of paramount importance. The architecture we have developed is per- fectly equipped to set up a network. A: If we stick to proven technology and standards, nothing can go wrong. B: But what is that, which standard is proven, which standard is commonly used, which one really works? C: Here we go again! In November 2005, the core team, made up of repre- sentatives of a few major participating organisations, at- tempted to tackle the problems experienced by calling the project team together for a two-day brainstorming session in a remote countryside hotel. The technology and stan dardi- sation issues had been declared settled, but still played a role, while the intention was to produce a strategy for developing a user-driven approach. The program for the session mentions a meeting with a public relations cons ult - ant and the question of how to bring more u ser -d riv en nes s into the project. In fact, user orientation was extensively discussed, eventually leading to a ‘motto’ of which the team was very proud: ‘Able to find and allowed to use’. The subsequent working conference, in which the pro- ject was to be presented to the GI community in Decem- ber 2005, w as also a pressing issu e. The p roject team h ad mixed feelings about whether there was anything tangi- ble to demonstrate and thought that if this was not the case, it would be better to cancel the presentation. After some deliberation it was agreed that a rudimentary ver- sion of the Red Portals would be demonstrated. Thus, in December 2005 the Geo Portals project was launched before a GI audience at the conference. The core team was determined to make a convincing state- ment by showing that the project was user-driven and was doing the right thing in terms of technology, but also felt a little uncertain. The audience was familiar with SGI and its projects and knew of the existence of the Geo Portals project, but was unfamiliar with the details. Sheer curiosity brought about fifty GI professionals together. In his introduction, the scientific director of SGI signi- fied the importance of Geo Portals for SGI, proclaiming it to be a key project. The core team then gave a presen- tation about the demand-drivenness of the project and elucidated the ‘motto’. Despite the importance with which this was regarded by the project tea m, it barely raised the interest of the audience. However, the demonstration of a rudimentary version of the Red Portals website using data from the built environment had an astonishing effect. What the Geo Portals team considered window-dressing was the very thing that convinced the audience of the pro- ject’s importance. In subsequent discussions it became apparent that participants were convinced that the Geo Portals project was SGI’s key project and that it was technically well managed and would make a difference. The Geo Portals project team celebrated the day as a success. 4.1.1 Narrative Setting, Space and Storyboard In this case, technology is the dominating factor in the narrative setting. In the past it has been an impediment w ith respe ct to in fr astru ctu re deve lop men t, but in thi s se tt ing thi s was no longer the case, the team considering it possible to apply GI technology for the disclosure of data in a way that society as a whole would benefit. In this setting, GI technology is seen as an ever-developing and changing phenomenon that will be mastered through the applica- tion of standards and result in an infrastructure with a rather static form, divided into thematically organised compart- ments of dat a t hat give it a ne atl y ar range d a ppe arance . In the narrative space, the project team has a direct re- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 341 lationship with the GI community. Individual project m em - bers belong to organisations that financially support the project, but these organisations are not recognised as indi- vidual pa rtne rs. As a whol e, the organi sation s have a neutral and minor role and are all seen as equal and as supporting the common cause of sharing GI data. GI data users are recognised as a defined group through the user motto, but a clear picture of these users has still not been dev eloped. A storyboard emerges concerning the propensity to let technology work for the GI sector through the application of standards. The Geo Portals project is seen to be acting on behalf of the entire GI sector, detached from individual organisations and creating a stable infrastructure. 4.2 Attempting to Reduce Uncertainty The project team continued its project meetings on a fixed day of the month in a centrally situated venue, with meet- ings held in a building occupied by one of the participat- ing organisations. The morning agenda was devoted to management matters, while discussions prepared by a core team member or an external speaker took place in the afternoon. However, fundamental issues would emerge d ur- ing the morning sessions and be discussed over lunch, sometimes continuing throughout the day, suggesting a certain level of insecurity. Nevertheless, a research pap er written by the project members to convince European peers expressed confidence [91]. The Geo Portals project was meant to provide all pos- sible kinds of data, to be delivered to both professional users and the general public. Professional users only needed disclosed data, while lay users could be provided with software services which had to be developed for inte- grating, harmonising and presenting data. Existing ex- amples of the disclosure of geo data through websites were reviewed, the flaws convincing the project mem- bers that there were many difficulties involved in bring- ing together different sources. Services designed to har- monise and present data were seen as essential to Geo Portals, emphasising the user orientation of the project, which was communicated to the GI commun ity. The core team developed the example of a beer brewer in need of geo information to assist in finding a location for a new brewing facility. In all the subsequent presentations and promotional material, including an SGI promotional film, this example–which connected different processes within different public organisations–was made prominent [92]. User orientation also generated interest in legal aspects and the issue of digital rights management. A researcher affiliated with Geo Portals translated an approach for r eg u- lating copyright on th e intern et into a model ap p licable to the field of geo information. This model, regulating legal and economic aspects of geo information, was regarded as essential for Geo Portals, although, however important it was felt to be, it was also seen as a separate entity, u n l i k e technological issues. Technology was held to be dynamic, while the access model was found to be static. Further development of the model was embedded in another SGI project, placing it beyond the control of the project team. At the end of 2006, the project team began to feel un- comfortable about the lack of steering capacity at SGI. While SGI saw Geo Portals as the core project of the program, the core team thought SGI, giving voice to the management of individual organisations, should provide an overarching framework. As SGI was seen as the cus- todian of the National Geo Information Infrastructure, a serious discussion among project participants was de- voted to this topic: A: We are supposed to work on NGII. For SGI, Geo Portals are considered as focal, but they don’t say any- thing about the guidelines we should follow or how to connect to other projects that are part of the NGII. B: They are talking about a test bed for NGII, but is NGII only a test bed? Are we supposed to deliver some- thing that actually works? C: We are certainly working on our data viewer, but to what standards should it comply? Are there any organi- sations that are going to use it? A: They say that a new GI coordinating organisation is in the making–yet another organisation that is supposed to organise something. We need guidelines and all they do is establish a new organisation. This does not sound like coordination to me! D: I think that as a Geo Portals team we should take a stand and do what SGI refuses: take the lead! The core team did not feel supported by SGI, which until then had been seen as the keeper of the National Geo Information Infrastructure, of wh ich Geo Portals w a s a part. At the end of 2006, SGI published an article in a leading professional magazine with the provocative title: ‘Where to with the Dutch Geo Information Infrastruc- ture?’ [93]. It provoked discussion and also made the core team feel that SGI had no strategy. Geo Portals concentrated on the work to be done: new services had to be developed with new software. Choices had to be made on what technology to use and what stan- dards to apply. The core team, representing three gov- ernment-supported knowledge institu tions and a software company, felt responsible for this part of the project and took up the challenge of drawing up a framework and organising software development. A participating engi- neering firm also did some work, but took little part in any conceptual, organ isational or management activities. During the software development process, the core team came together on a weekly basis to coordinate software development which was undertaken by software engineers from core team member’s organisations. In spring 2007, these efforts resulted in a data viewer, a software device designed to be capab le of consistently retrieving g eo data from different sources on a computer screen. The Geo Portals core team, being enthusiastic about it, saw it as a Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 342 requirement for bringing the ultimate goal, a system of Geo Portals, one step closer. While celebrating this achievement, project me mbers s oon felt that the newly developed data viewer was already becoming outdated because new techniques were now available. This gave software engineers the opportunity to develop even more sophisticated viewers. Thus, whi le having a tested product ready for implementation, the development process went on, with an enthusiastic core team managing the same team of software developers. While working with the newest technologies they gave the impression that these developments were quite normal for them–new technology had to be explored and applied. 4.2.1 Narrative Setting, Space and Storyboard In this phase of the project, the narrative setting becomes increasingly dominated by technology. To serve lay users, services have to be developed using state-of-the-art tech- nology. Standards are still important but they are ap- praised as being of lesser concern. Legal aspects are seen as a separate area that needs to be dealt with, but not necessarily by the project management team. In the narrative space, the management of individual participating organisations is seen as collectively organ- ised into advisory boards of the SGI program. The pro- gram itself is considered to be unsupportive, as it simply does not have a policy, and those on the boards are not seen as GI experts, but as serving the interests of indi- vidual organisations, which are not necessarily the inter- ests of the Geo Portals project. Those involved in the Geo Portals project must recognise that in order to be successful they must plot their own course, which will be to address the newest trends in GI technology. The storyboard at this stage is at the po int of exploring the latest GI technology and incorporating this into a test website. Once the technology is ready to be used as a building block for GI infrastructure, further effort will be put into assessing newer technological improvements. 4.3 Towards Judgement Day In 2007, the Geo Portals project was on track as far as software development was concerned, but the core team was becoming increasingly agitated, feeling that the ini- tial goal of sharing geo information was moving out of reach. At the project team meeting in April 2007, a dis- cussion on this point was initiated by two core team members in an attempt to engineer a breakthrough: It is terribly sad that we cannot build on the achieve- ments of SGI. It looks like management does not recog- nise what it is all about. In the Netherlands we have an abundance of geo data, distinguished scholars, high GIS penetration, a vast and schooled workforce and many knowledge exchange networks. Perfect circumstances for great ideas. But guess what? We just keep on chatting! Nobody seemed to be in charge of developing the N GI I, and the decision-makers at SGI were depicted as abstract thinkers with no practical knowledge. It was felt that a breakthrough was needed, and the appraisal of the SGI promotional conference held in March 2007 did not dis- play any confidence: A: I am sad to say that real sharing of geo information is further away than ever. We have just had the SGI con- ference in Rotterdam. It lacked any ambition. The bottom line was: ‘The NGII has to be developed, but let’s move on as we did’. That’s not the way to get it done. B: It was a convention of the same people that you see all the time at such events; ‘the usual suspects’ were do- ing their ritual thing. C: It was like being in some religious rally, people celebrating and praising something of which everybody has a different image. B: It is a paradoxical situation. When we need a break- through, surprise, surprise, nobody wants to change, we keep on doing things the way we did, and nothing really changes. C: Everybody talks about the costs of an NGII, the benefits are not mentioned. A: An NGII will add v alue, that’s the raison d’ être. If we only want an NGII for incident management and fighting terrorism we’re on the wrong track. Despite the uncertainty, Geo Portals was considered to be successful because it offered technical solutions. The technology only had to be brought to a meaningful con- clusion in order to establish the NGII, but failing man- agement seemed to obstruct this. Perceptions of the role of Geo Portals started to change: It is perfectly clear that it was unattainable to build an infrastructure. Just look at the budget we had for this project: it was clear even before we started that it was insufficient. Our job was to deliver building blocks, to innovate for the sake of an NGII. We are good at the technological aspects. So if they ask us for such a project, we will handle technology. Without any guidance from SGI, it is impossible to de- velop an NGII. What we can offer for a future NGII is best practices and software tools. We form a community for NGII development. Another working conference was organised for Novem- ber 2007 with a striking theme: ‘Just do it’. External ex- perts were asked to focus on financial, legal and organ- isational aspects, while Geo Portals project members were keen to present the technical aspects. The message in workshops was that new software applications, as devel- oped by Geo Portals, were fully capable of integrating geo data from different sources. This message was symbol- ised using Lego blocks, representing geo data building blocks which could be put together in any possible way. Now that the finish was in sight, the project team wanted to deliver results which could be used in the fu- ture. Slowly but steadily, the project goals were redefined. The obligation to produce tangible products changed, with the Geo Portals team coming to see itself as a ‘commu- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 343 nity of practice’. The image of the project as developing building blocks for an NGII now changed, with Geo Portals being reconceived as a knowledge-creating project. The atmosphere also changed, from distress to optimism to euphoria, although one of the more sceptical project team members noted that what was occurring was ‘ex- pectation management’. It was felt that the positive results should be dissemi- nated to the GI commu nity, for examp le in a resear ch pa p er [94], and a new sector-wide policy coordinating organi- sation called Geonovum began to promote itself. While the Geo Portals project team had at first thought that this organisation was covering up the failings of the geo in- formation sector, they now thought that Geonovum could secure the innovative achievements of Geo Portals for the future. The image of SGI changed accordingly, from being purely involved in funding to becoming a knowl- edge-boosting program that should be continued. At the closing conference in December 2008 there was confidence about the results. The highest civil servant responsible for geo information in the Ministry of Hous- ing, Spatial Planning and the Environment was the key- note speaker, addressing 150 people in a prestigious loca- tion. A specially produced video presented the improve- ment of the accessibility of geo information as an ongo- ing project, suggesting that there was much work still to be done. Software applications were presented as step- ping stones in a continuou s progression, invoking a great deal of interest in newly developed techniques. A new website wit h a new nam e (Ca rt a Fab rica ) wa s also launched, where the achievements of Geo Portals were to be made available. Both the core team and the audience were op- timistic about the future. In interviews held after the completion of the project, the image of technology as dominating all developments was persistent. Standards were seen as a thing of the past because technology was now seen as being capable of connecting all forms of data. The approach was referred to as ‘Web 2.0’, signifying that the new technology was obviously web-based. It was also noted by Geo Portals project members that Geonovum was still working on a National Geo Register aiming at the registration and stan- dardisation of all governmental geo data but that this project was obsolete because Web 2.0 would solve all the con- nection problems where standardisation had failed. How- ever, most importantly, the National Geo Register was seen as a project that hampered innovation in the geo information sector. 4.3.1 Narrative Setting, Space and Storyboard In the narrative setting, technology is now treated as the essence of Geo Portals. Technology is seen as an un leashed phenomenon, now labelled as ‘innovation’, and it is ready to solve any problem, with the aim of making the world a better place. Innovation is thus seen as an enabler of dy- namic geo information management, without being chaine d by standards. However, the solutions created by this technology are found to be obsolete before they can be used, not because they do not function properly but be- cause they are superseded by solutions powered by even more sophisticated technology. In the narrative space, both diverging and converging tendencies can be observed. The GI sector management, speaking through organisations such as Geonovum and SGI with their emphasis on standards, is found by Geo Portals project members to inhibit the possibilities cre- ated by the application of technology. By providing in- sufficient funding they are also seen as responsible for not delivering Geo Portals as originally planned. Realis- ing that the initial goals were untenable, the Geo Portals team redirected their aim towards creating innovation to facilitate the creation of an NGII. As the SGI was sup- posed to stimulate innovation in g eo information sharing, the Geo Portals project team felt quite comfortable with their new goals, knowing that their project would stimu- late innovation. The storyboard that can be identified here aims at the production of new technologies which could be made available to the GI sector. It affects the reframing of goals, moving from the creation of a static infrastructure into making new technologies available. This reframing is justified through concluding that the funds originally granted by SGI were inadequate to realise the GI infra- structure considered in th e initial plan. 5. Discussions In this paper, we have used the framework of narrative setting, space and storyboard to analyse the Geo Portals project. Three phases of the project were identified, in which the narrative setting and space could be placed in a relationship with a developing storyboard. The Geo Por- tals project had a clear beginning and end, and there were also some preparatory activities which were considered to be important for the analysis, as well as the impact of the project on the Dutch GI sector. Initially, the Geo Portals project proposal was to de- velop an infrastructure serving societal needs. These needs were converted into user profiles with different demand structures. As project participants became dissatisfied with the lack of guidelines for an overarching strategy, they started to develop software applications. Because they considered themselves to be the vanguard of ever- changing technology, the idea of building an infrastruc- ture slowly faded. Consequently, the goal shifted towards providing a toolbox, which in turn changed into the im- age of the project as stimulating innovation. The narrative setting, dominated by rapidly developing information technology, encouraged project participants to look to the future, and the Geo Portals project acted as a means to deal collectively with this task and to apply the latest technology to create newly developed software applications. Geo Portals project members, acting inde- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 344 pendently of their respective organisations, made new technology available, while unintentionally ensuring that no individual or organisation could be blamed for failure. Because the Geo Portals project was supposed to be benefi- cial to the whole GI sector, the project team decided to supply state-of-the-art technology. In the narrative space, SGI was seen as an enabling organisation, acting on behalf of the Dutch GI commu- nity, in relation to which the Geo Portals project would be beneficial to the whole sector. The Geo Portals project team saw SGI as a temporary organisation, being part of the GI community and primarily involved in sustaining the Geo Portals concept through funding with money budgeted for the GI community. This relationship made the project team cautious, responsible and somewhat self- reflective. Thus, SGI brought the GI community to gether around a financing source, forcing individual organisa- tions to cooperate with each o ther in order to be eligible for funding. The analysis shows a cyclical storyboard: whenever new technology was tested and approved, newer tech- nology was already virtually available to be tested and eventually to be confirmed as a new standard. The data shows two of these cycles, with the typical pattern being depicted in Figure 2. This is the storyboard of the action occurring within the project, which can also be inter- preted as a vicious circle [95]. In a world with a pressing and increasing turnover of technological innovations, reliable infrastructures might create stability. The two competing narratives of stability and change always struggle for dominance. An infrastruc- ture is a fixed, predictable, stable, unambiguous and ubiq- uitous facility that users almost tak e for granted [96] and a focus on the development of a standardised infrastructure utilises the narrative of stability, a prominent f ea tu re in t he initial Geo Portals project proposal. The difficulties in- volved in standardisation were already recognised in the project’s subtitle: ‘liberty united’ and a strict regime of standardisation was also feared, as well as being consid- ered difficult to implement. Therefore, a limited, ‘light’ version of standard isation was proposed. Throughout the project, fro m the initial presentation of the Red Portals, which was hailed as innovativ e, until the conclusion, when the entire Geo Portals project was de- clared innovative, the emphasis was on change. Newly developed software, already obsolete on the day of its realisation, was not considered a problem. Moreover, it was seen as essential, as the average GI professional sees tomorrow’s technology as the solution to problems en- countered today. The storyboard of innovation remains prominent. The core message of SGI, to be innovative, hampered the de- velopment of an infrastructure. For this reason, the project was reframed i nto a knowled ge-generatin g endeavour, driven Figure 2. The storyboard of innovation by a storyboard of innovation. Ultimately, the GI com- munity would judg e the proj ect on its in novative q u alities, presented through state-of-the-art software. While this is a tangible result of the four-year Geo Portals project, it is only temporary, with no reference to infrastructure. 6. Conclusions Delivering infrastructure seems to involve two contra- dictory aspects [97]. On the one hand there is a narrative of change, expressing the urge to work with the newest technology, and on the other hand there is a narrative of stability which sees infrastructure as predictable and sta- ble and thus useful. These two narratives seem to fight for attention. As the Geo Portals program basically aimed at innova- tion, the narrative of change was dominant, and can be identified in the innovation storyboard. Infrastructure de- velopment rather than infrastructure building was paramount, and thus a stabl e, recognisa ble infrastructure was abse nt. The narratives reflect the basic stability/change con- tradiction [66]. The confrontation of these two differing narratives is not uncommon and has been called the ‘in- novation paradox’. It is found in large public sector pro- jects where a fixed infrastructure has to be delivered in an unstable environment [49]. It has been suggested that when problems with the construction of infrastructures emerge it is necessary to focus on project designs in the light of cultural settings [98]. However, here there was more at stake. A GI commu- nity, seemingly preoccupied with innovation, desperately required a useable infrastructure. While one of those in- volved in the project suggested that infrastructures are always in a process of innovation and should be regarded as ‘moving targets’, in order to be used, infrastructures also need to be stable. Thus, the sector as a whole must find equilibrium between stability and change in relation to infrastructure. Now th at these d riv ing forces hav e been identified, a breakthrough is within reach. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 345 REFERENCES [1] J. Crompvoets, “National spatial data clearinghouses, wo r l d - wide development and impact,” Wageningen Universiteit, Wageningen, 2006. [2] A. Rajabifard and I. Williamson, “Spatial data infrastruc- tures: Concept, sdi hierarchy and future directions,” Geo- matics 80, Tehran, Iran, 2001. [3] D. Nebert, “The SDI cookbook,” 2004. http://www. gsdi. org/pubs/cookbook/ [4] F. de Bre e an d A . Raj abif ard , “ In volv in g us e rs in th e process of using and sharing geo-information within the context of SDI initiatives,” Pharaohs to Geoinformatics, FIG Work- ing week, 20 05. [5] I. Masser, “GIS worlds: Creating spatial data infrastruc- tures,” ESRI Press, Redlands CA, 2005. [6] Y. Georgiadou, S. K. Puri, and S. Sahay, “Towards a potential research agenda to guide the implementation of Spatial Data Infrastructures: A case study from India,” International Journal of Geographical Information Sci- ence, Vol. 19, No. 10, pp. 1113–1130, 2005. [7] J. Crompvoets et al. eds, “A multi-view framework to assess SDIs,” Space for Geo-Information (RGI), Wagen- ingen University and Centre for SDIs and Land Admini- stration, Department of Geomatics, University of Mel- bourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [8] H. Koerten, “Assessing the organisational aspects of SDI: Metaphors matter,” A Multi-View Framework to Assess SDIs, J. Crompvoets et al., Editors, Melbourne, pp. 235– 254, 2008. [9] Y. Georgiadou, O. Rodriguez-Pabón, and K. Lance, “Spatial data infrastructure (SDI) and e-governance: A quest for appropriate evaluation approaches,” URISA Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 43–55, 2006. [10] W. van den Toorn and E. de Man, “Anticipating cultural factors of GDI,” in Geospatial data infrastructure: Con- cepts, cases and good practice, R. Groot and J. McLauglin, Editors, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000. [11] E. de Man, “Cultural and institutional conditions for us- ing geographic information: Access and participation,” URISA Journal, Vol. 15(APA I), pp. 29–33, 2003. [12] H. Koerten, “Blazing the trail or follow the Yellow Brick Road? On geo-information and organizing theory in GI days,” Young researchers Forum, 10–12 September 2007, F. Probst and C. Kessler, Editors, Institut für Geo-infor- matik, Universität Münster: Münster, Germany, pp. 85– 104, 2007. [13] D. Hodgson and S. Cicmil, eds., “Making projects criti- cal,” in Management, Work and Organisations, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2006. [14] A. van Marrewijk and M. Veenswijk, “The culture of project manageme nt: Understanding daily life in complex megapro- jects,” Pearson Education Lim ited, H arlow, UK , 20 06. [15] H. Blumer, “Symbolic interactionism, perspective and method,” Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs ,NY, 1969. [16] G. Ritzer, “Modern sociological theory,” Mc Graw-Hill International Editions, NY, 1996. [17] E. Goffman, “The presentation of self in everyday life,” Doubleday Garden City, NY, 1959. [18] G. Goffman, “Frame an alysis,” H arper & Row, NY, 1974 . [19] G. Gonos, “‘Situation’ versus ‘Frame’: The ‘Interactionist’ and the ‘Structuralist’ analysis of everyday life,” American Sociological Review , Vol. 4 2, pp. 8 54–867 , 1977. [20] P. Manning, “Erving Goffman and modern sociology”, Stanford University Press, Stanford CA, 1992. [21] J. Habermas, “The theory of communicative action,” Life- world an d S ystem , Be acon Pres s, Bost on MA , V ol. 2 , 1 987. [22] A. Giddens, “Modernity and self-identity: Self and mod- ernity in the late modern age,” Stanford University Press, Stanford CA, 1991. [23] U. Beck, “Risk society,” Sage Publications, Newbury Park, California, 1992. [24] G. Ritzer ed., “The McDonaldization of society revised edition,” Pine Forge Press, Thousand Oaks CA, 1996. [25] A. Giddens, “Central problems in social theory: Action, structure and contradiction in social analysis,” Basing- stoke, MacMillan, 1979. [26] M. Archer, “Culture and agency: The place of culture in social theory,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1988. [27] P. Bourdieu and D. Pels, “Opstellen over smaak, habitus en het veldbegrip,” Van Gennep, Amsterdam, 1989. [28] P. L. Berger and T. Luckmann, “The social construction of reality,” Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1967. [29] K. Gergen, “Realities and relationships, soundings in social construction,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1994. [30] D. Boje, “Stories of the storytelling organization: A post- modern analysis of Disney as ‘Tamara-Land’,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 4 , pp. 997 –1035 , 1995. [31] M. Berendse, H. Duijnhoven, and M. Veenswijk, “Editing narratives of change, identity and legitimacy in complex innovative infrastructure organizations,” Intervention Re- search, pp. 73–89, 2006. [32] D. Polkinghorne, “Narrative knowing and the human sci- ences,” State University of New York Press, NY, 1988. [33] M. Hatch and D. Yanow, “Organization theory as an in- terpretive science,” The Oxford Handbook of Organiza- tional Theory, C. Knudsen and H. Tsoukas, Editors, Ox- ford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2003. [34] K. Verduijn, “Tales of entrepreneurship, contributions to understanding entrepreneurial life,” PhD thesis Vrije Univer- siteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 2007. [35] P. Ricoeur, “The model of the text: Meaningful action considered as text”, New Literary Society, Vol. 5, pp. 91– 120, 1973. [36] C. Oswick, T. Keenoy, and D. Grant, “Discourse, organi- zations and organizing: Concepts, objects and subjects,” Human Relations, Vol. 53, No. 9, pp. 1115–1124, 2000. [37] D. Grant, et al., eds, “Introduction: Organizational dis- course: Exploring the field,” The Sage Handbook of Or- ganizational Discourse, Sage Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks CA, pp. 1–36, 2004. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation 346 [38] D. Grant, T. Keenoy and C. Oswick, eds, “Discourse + Or- ganization,” Sage Publications Ltd , Lon don, UK, 19 98. [39] N. Frye, “Anatomy of criticism: Four essays,” Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1957. [40] K. Burke, “A grammar of motives,” University of Cali- fornia Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1969. [41] K. Gergen, “An invitation to social construction,” Sage, London, 1999. [42] Y. Gabriel, “St orytelling in orga nizations, facts, fictions, and fantasies,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2000. [43] T. Peters and R. Waterman, “In search of excellence, le ss ons from America’s best-run companies,” Harper & Row, New York, 1982. [44] S. Hel mer s an d R. Buh r, “ Cor por a t e s t o ry-telli n g: The buxom- ly secretary, a pyrric victory of the male mind,” Scandi- navian Journal of Management, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 175– 191, 1994. [45] E. Schein, “Culture: The missing concept in organization studies,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 229–240, 1996. [46] J. Brown, et al., “Storytelling in organizations: Why storytel- ling is transforming 21st century organizations and manage- ment,” Butterworth-Heinema nn, Burlington MA, 2005. [47] A. Brown, P. Stacey, and J. Nandhakumar, “Making sense of sensemaking narratives”, Human Relations, Vol. 6, No. 8, pp. 1035–1062, 2008. [48] K. E. Weick, “Sensemaking in organizations”, Sage Pub- lications, London, 1995. [49] M. Veenswijk, “Surviving the innovation paradox: The case of Megaproject X,” The Innovation Journal, The Public sector Innovation Journal, Vol. 11, pp. 2, article 6, pp. 1–14, 2006. [50] J. Bruner, “The narrative construction of reality,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 18, pp. 1–21, 1991. [51] M. Alvesson and D. Karreman, “Variety of discou rse: On the study of organizations through discourse analysis,” Human Relations, Vol. 53, No. 9, pp. 1125–1149, 2000. [52] C. Kohler Riessman, “Narrative analysis,” Sage Publica- tions, Newbury Park CA, Vol. 30, 1993. [53] B. Czarniawska-Joerges, “A narrative approach to organiza- tion studies,” Sage Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks CA, Vol. 43, 1998. [54] D. Yanow, “Conducting interpretive policy research,” Sage Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks CA, 2000. [55] D. Boje, “Narrative methods for or ganizational a nd commu- nication resear ch”, S age Publicatio ns Ltd , London, 2 001. [56] S. Tesselaar, I. Sabelis, and B. Ligtvoet, “Digesting sto- ries: About the use of storytelling in a context of organ- izational change,” in 8th International Conference on Or- ganizational Discourse 2008, London, UK, 2008. [57] N. Beech and C. Huxham, “Cycles of identity formation in inter-organizational collaborations,” International Stud- ies of Management & Organization, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 28–52, 2003. [58] T. Deal and A. Kennedy, “Corporate cultures: The rites and rituals of corporate life,” Penguin, 1982. [59] H. Bergson, “The creative mind,” Greenwood Press, West- port CT, 1946. [60] G. Burrell, “Back to the future: Time and organization, in rethinking organization, new directions in organization theory and analysis,” M. Reed and M. Hughes, Editors, Sage Publications Ltd, London, UK, pp. 165–183, 1992. [61] G. Burrell, “Time and talk,” Organization, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 371–372, 2000. [62] R. Chia, “Essay: Time, duration and simultaneity: Rethink- ing and change in organizational analysis,” Organization Studies, Vol. 23, No. 6, pp. 863–868, 2002. [63] M. Heidegger, “Sein und zeit [Being and time],” Tübin- gen D, Max Niemeyer, 1977. [64] B. Czarniawska-Joerges and G. Sevón, eds, “Translating organizational change,” ed. A. Kieser, de Gruyter Stud- ies in Organization, Walter de Gruyter, Berli n, Germany, Vol. 56, 1996. [65] E. Schein, “Organizational culture and leadership,” Jossey Bass, 2nd Edition, 1992. [66] M. Douglas, “How institutions think”, Syracuse Univer- sity Press, Syracuse, 1986. [67] S. Chreim, “The continuity-change duality in narrative texts of organizational identity,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 567–593, 2005. [68] R. Harré, “Life sentences, aspects of the social role of language,” John Wiley & Sons, London, UK, 1976. [69] H. Lefebvre, “The production of space,” Blackwell Pub- lishers, Oxford, UK, 1991. [70] W. R. Scott, “Institutions and organizations,” Sage Pub- lications, 1995. [71] D. Yanow, “Built space as story: The policy stories that buildings tell,” Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 407–422, 1995. [72] D. Yanow, “How built spaces mean, in interpretation and method: Empirical research methods and the interpretive turn,” D. Yanow and P. Schwartz, Editors, M. E. Scharpe, Armonk NY, 2006. [73] M. Gastelaars, “Talking stuff: What do buildings tell us about an or ganization’s sta te of affairs?” in 8th International Conference on Organizational Discourse, London, UK, 2008. [74] B. Schneider, “The people make the place,” Personnel Psychology, pp. 437–453, 1987. [75] W. Orlikowski, “Using technology and constituting struc- tures: A practice lens for studying technology in organi- zations,” Organization Science, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 404– 428, 2000. [76] W. Bijker, “Of bicycles, bakelites, and bulbs, towards a theory of sociotechnical change,” The MIT Press, Cam- bridge, 1995. [77] W. Orlikowski, “Sociomaterial practices: Exploring tech- nology at work,” Organization Studies, Vol. 28, No. 9, pp. 1435–1448, 2007. [78] M. Lipsky, “Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services,” Russell Sage Foundation, New York, 1980. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Narrating National Geo Information Infrastructures: Balancing Infrastructure and Innovation Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 347 [79] S. Barley, “The alignment of technology and structure through roles and networks,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 35, pp. 61–103, 1990. [80] J. Bartunek, “The importance of contradictions in social interventions,” Intervention Research, Vol. 1, pp. 103– 113, 2004. [81] S. Ybema, “Constructing collective identity : Central , disti nc- tive and enduring characteristics?” in 8th International Con- ference on Organizational D iscour se, Londo n, UK, 2008. [82] H. Garfinkel, “Studies in ethno methodology,” Polity Press, Cambridge, 1984. [83] E. Wenger, “Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1998. [84] B. Latour and S. Woolga r, “Lab orator y lif e: Th e constr uction of scientific facts,” Princeton University Press, 1986. [85] K. Golden-Biddle and K. Locke, “Appealing work: An investigation of how ethnographic texts convince”, Or- ganization Science, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 595–616, 1993. [86] H. Duijnhoven, “Tales of Security practices within Span- ish and Dutch railway operators: Translation, transforma- tion or transgression?” in 8th International Conference on Organizational Discourse, London, UK, 2008. [87] T. Watson, “Ethnographic fiction science: Making sense of managerial work and organizational research processes with Caroline and Terry,” Organization, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 489–510, 2000. [88] RAVI, “Space for geo-information BSIK knowledge project proposal,” RAVI, Amersfoort, 2003. [89] A. Schmidt and G. Nieuwenhuis, “Geoportals ‘Liberty United’,” Project proposal for space for geo information, Wageningen, 2002. [90] M. Hoogerwerf and B. Vermeij, “Geoportal framework version 0.2,” (Geoloketten Raamwerk versie 0.2), 2005. [91] J. Zevenbergen et al., “Connecting the Dutch geo-infor- mation network–liberty united,” UDMS, Aalborg, Den- mark, 2006. [92] D. van de Laak, “DVD: Alles draait om geo,” Ruimte voor Geo-Informatie, Neth erlands, 200 7. [93] A. Bregt and J. Meerkerk, “Waarheen met de nationale geo-informatie infrastructuur?” Geo-Info, Vol. 7/8, pp. 296–301, 2006. [94] J. Zevenbergen, et al., “‘Geoportal Network’: More process catalyst than project,” UDMS, Ljubljana, Slo- venia, 2009. [95] M. Masuch, “Vicious circles in organizations,” Administra- tive Science Quarterl y, Vol. 30 , No. 1 , pp. 1 4–33, 19 85. [96] P. Edwards, et al., “Understanding infrastructure: Dy- namics, tensions, and design,” Report of a Workshop on “History & theory of infrastructure: Lessons for new sci- entific cyberinfrastructures,” 2007. [97] O. Hanseth, E. Monteiro, and M. Hatling, “Developing informati on in frastr uctu re: The te nsion be twee n standa rd iz a - tion and flexibility,” Science, Technology & Human Values, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 407–426, 1996. [98] A. van Marrewijk, et al ., “Managing public-private m e ga pr o - jects: Paradoxes, complexity, and project design,” Inter- national Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26, pp. 591–600, 2008. |