J. Service Science & Management, 2009, 2: 289-304 doi:10.4236/jssm.2009.24035 Published Online December 2009 (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 289 How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed Julia Hein, Thomas Weber Department of Economics, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany. Email: Thomas.A.Weber@uni-konstanz.de Received July 24, 2009; revised August 29, 2009; accepted October 3, 2009. ABSTRACT Several policy options have been discussed to mitigate the current subprime mortgage crisis. This paper analyses an interest rate freeze on adjustable rate mortgages as one possible reaction. In particular, the implications on Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS) are studied. We examine shifts in the underlying portfolio’s discounted cash flow distributions as well as changes in the payment profile of RMBS-tranches. We show that the positive effects of a rate freeze, e.g. less foreclosures and a stabilizing housing market, can outweigh the negative effect of lower interest income such that investors might be better off. Keywords: Interest Rate Freeze, Subprime Mortgages, Residential Mortgage, Backed Securities (RMBS) 1. Introduction Starting in mid 2007, rising delinquency and foreclosure rates in the US subprime mortgage market triggered a severe financial crisis which spread around the world. Although subprime mortgages, that were granted to bor- rowers with weak credit record and often require less documentation, only account for about 15 percent of all outstanding US mortgages, they were responsible for more than 50 percent of all mortgage loan losses in 2007 [1]. Most of the subprime losses were caused by high foreclosure rates on hybrid adjustable rate mortgages (ARM). These loans offer fixed initial interest rates at a fairly low level, which are replaced by higher rates linked to an interest rate index after two or three years1. Thus, borrowers face a significant payment shock after the interest reset which increases the probability of de- linquencies. In previous years, rising real estate prices and, thus, increasing home owner equity enabled mort- gage associations to waive part of delinquent interest payments in exchange for an increase in nominal value of the mortgage or to renegotiate the mortgage. But during the last year the trend in real estate prices has reversed in many regions of the United States leading to “negative equity” of many borrowers, i.e. to real estate values that are lower than their outstanding debt. Consequently, de- fault rates increased2. Several policy options have been discussed to tackle this crisis. The primary concern of policy makers was to lower the financial burden of subprime borrowers and, thus, to avoid further delinquencies and foreclosures which in turn may stabilize house prices. The first policy option is to provide direct financial support by disbursing money to borrowers. In fact, this has been done in Feb- ruary 2008 by means of the Economic Stimulus Act 2008, which included tax rebates amounting from $300 to $600 per person. Whereas this policy action benefited every tax payer and was not directly linked to the mortgage loans, the Housing Bill of July 2008 was especially targeted to subprime borrowers. Here a second policy option was taken by providing state guarantees for mort- gage loans. Thus, borrowers, who are close to foreclosure, can refinance their loans at lower interest rates. Although both policy actions certainly help to improve the situa- tion of borrowers, the big drawback of these instruments is that they are mainly financed by the tax payer who cannot be blamed for the crisis. In contrast, mortgage banks, who have been criticized for lax lending standards [2], benefit from less defaults without accepting a re- sponsibility. 1According to the IMF [1], $ 250 billion subprime mortgages are due to reset in 2008. 2Mortgage loan contracts in the United States often exclude personal liability such that borrowers do not face any further financial urden when the default.  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed 290 A third policy option, which takes the banks’ failure into account and which was proposed by the US gov- ernment on December 6th, 2007, is an interest rate freeze. This means that banks agree to waive (part of) the inter- est rate step up on their ARMs. Although this proposal did not become effective it raises the question whether such an instrument may be better suited to mitigate the current crisis. The aim of this paper is therefore to inves- tigate the implications of an interest rate freeze. Of course, subprime debtors will benefit from this measure through reduced interest obligations. In contrast, the effect on the lenders is not a priori clear. On the one hand, they receive lower interest on a significant portion of mortgage loans. On the other hand, they might benefit in a twofold way. First, the number of defaults potentially declines. Second, the average loss given default (LGD) might be lower when house prices stabilize. Conse- quently, there will be a shift in the repayment distribution of the mortgage loan portfolio, which will be examined in the paper. But the impact of an interest-rate freeze is not limited to borrowers and lenders. More than half of all subprime mortgages that were granted in recent years were sold in residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS). In these RMBS transactions cash flows from the underlying mortgage pool are allocated to tranches with different seniority: several rated tranches and an equity tranche. Due to a priority of payments scheme the equity tranche absorbs most of the losses whereas the senior tranche exhibits only low risk. Part of the RMBS tranches were purchased by outside investors, i.e. foreign banks, non- mortgage banks, insurance companies. As (part of) the mortgage interest payments is used to cover losses that otherwise might hit the rated tranches, RMBS investors lose part of their loss protection following an interest rate freeze. However, they also benefit from potentially lower default losses. The combined effects lead to a realloca- tion of cash flows and losses among investors which will also be analysed in this paper. Throughout the paper we look at three sample portfo- lios: two subprime RMBS portfolios, from which one is well diversified across regions and the other is geo- graphically concentrated in regions that are later hit hardest by the crisis, and one portfolio representing the US mortgage market as a whole. First, we simulate the stochastic repayments of each single mortgage loan using Monte Carlo simulation. In particular, we use the re- gional house price index as the systematic factor driving the default rate as well as the loss given default. Addi- tionally, we assume that each increase in the payment obligations of a debtor, e.g. through an interest rate step up, raises the default probability. Taking regional diversi- fication into account, we aggregate the single payments to get the repayment distributions of the mortgage loan portfolios underlying the different RMBS transactions. For all three portfolios we further assume a true-sale RMBS transaction with four differently rated tranches and an equity piece. We use a benchmark scenario with- out crisis elements to calibrate the sizes and loss protec- tion of the tranches to the respective rating. This scenario includes an interest rate step-up after year two for non- prime mortgage loans. Subsequently, we derive the portfolio repayment dis- tributions and the resulting tranche characteristics in a crisis scenario that reflects the current situation in the United States. In particular, the average house prices are assumed to have decreased by six percent in the second year of the RMBS transaction. As we show, the crisis leads to a significant reduction of the expected dis- counted cash flows of the respective portfolios ranging from five percent for the US market portfolio to more than 15 percent for the non-diversified subprime portfo- lio. Hence, the equity piece often does not suffice to cover the losses which means that the rated tranches need to absorb a significant share of the portfolio loss. Conse- quently, the risk characteristics of all tranches worsen as compared to the benchmark case which makes severe downgrades necessary as observed in the markets. Starting from this crisis scenario we investigate the impact of an interest rate freeze. We assume all sched- uled interest rate step-ups to be waived which decreases the claims on the RMBS portfolio. As subprime borrow- ers evade this payment shock, foreclosure rates decrease. First, we study only this direct effect of an interest rate freeze. Our simulation results show that the net change in expected portfolio payments is negative as is the effect on most tranches. The consequences are not uniform for all tranches however: the better the tranche, the less its characteristics deteriorate. The senior tranches of the two subprime RMBS even improve. In the second case, we additionally include a posi- tive ’second round’ effect on house prices. In particular, the lower number of foreclosures takes pressure off the housing market resulting such that the negative down- ward trend is stopped. Given this combined impact, our results indicate that the positive effects are able to (over-) compensate for the loss due to the interest rate freeze. In particular, all rated tranches benefit in this scenario as compared to the crisis scenario. Therefore we conclude that an interest rate freeze on mortgage loans does not only improve the debtor situation, but might also render investors in RMBS tranches better off at the expense of the equity tranche which takes most of the crisis losses. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First we comment on related literature. Section 3 de- scribes the set-up and calibration of our simulation model. In Section 4, we analyse the effects of a mortgage crisis on our sample mortgage portfolios and also on RMBS- tranches backed by these portfolios. Furthermore, we investigate the consequences of an interest rate freeze on Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed291 portfolio and tranche characteristics. Section 5 concludes. 2. Literature Review Our paper is closely related to the empirical study by Cagan [3] analysing the impact of an interest rate reset in adjustable rate mortgages (ARM). Based on a dataset of ARMs originated between 2004 and 2006, he estimates that 59% of these mortgages face a payment increase of more than 25% after the initial period with low rates. He anticipates that in total approximately 13% of adjust- able-rate mortgages will default due to the interest rate reset, which corresponds to 1.1 million foreclosures over a total period of six to seven years. This increase in de- fault rates is not equally distributed across all mortgages but depends on the size of the interest rate step-up and the loan-to-value ratio. Additionally, the author estimates that each one-percent fall in national house prices causes an additional 70,000 loans to enter reset-driven foreclo- sure. Given a house price drop of 10% he projects that more than 22% of ARMs will default due to the interest rate reset. This underlines the impact of a policy reaction to scheduled interest rate step-ups in the present market environment. Ashcraft and Schuermann [4] discuss the securitization of subprime mortgages. First they provide a detailed analysis of the key informational frictions that arise dur- ing the securitization process and how these frictions contributed to the current subprime crisis. They also doc- ument the rating process of subprime mortgage backed securities and comment on the ratings monitoring process. They conclude that credit ratings were assigned to sub- prime RMBS with significant error which has led to a large downgrade wave of RMBS tranches in July 20073. Several further research articles provide general in- formation about subprime loans and the current mortgage crisis. Chomsisengphet/Pennington-Cross [5] comment on the evolution of the subprime market segment. In par- ticular, some legal changes in the beginning of the 1980s, which allowed to charge higher interest rates and higher fees on more risky borrowers and which permitted to offer adjustable rate mortgages, enabled the emergence of subprime loans. The Tax Reform Act in 1986 allowing interest deductions on mortgage loans made high loan- to-value (LTV) ratios financially more rewarding and, thereby, sub-prime mortgages more attractive. In the be- ginning of the 1990s the increasing use of securitizations as funding vehicles triggered rapid growth in the sub- prime mortgage market. Between 1995 and 2006 the volume in this market segment increased from $ 65 bil- lion to more than $ 600 billion and also the share on the total mortgage market significantly increased [6]. At the same time the percentage of the outstanding subprime loan volume being securitized went up from about 30% to around 80% [2]. Dell’ Ariccia et al. [7] show that the rapid expansion of the subprime market was associated with a decline in lending standards. Additionally, they find that especially in areas with higher mortgage securi- tization rates and with more pronounced housing booms lending standards were eased. Lower lending standards can thus be identified as one reason for the subprime mortgage crisis. According to the IMF [1], subprime borrowers typi- cally exhibit one or more of the following characteristics at the time of loan origination: weakened credit histories as indicated by former delinquencies or bankruptcies, reduced repayment capacities as indicated by low credit scores or high debt-to-income ratios and incomplete credit histories. Given this very broad definition subpri- me borrowers are not a homogeneous group. For exam- ple, Countrywide Home Loans, Inc. distinguishes four different risk categories of subprime borrowers4.These subcategories may depend on the borrower’s FICO (Fair Isaac Corporation) credit score, which is an indicator of the borrowers credit history, the Loan-To-Value (LTV) ratio of the mortgage loan, and the debt-to-income ratio5. Analysing a data set of securitized loans from 1995 to 2004, Chomisengphet/Pennington-Cross [5] find strong evidence for risk-based pricing in the subprime market. In particular, interest rates differ according to credit sco- res, loan grades and loan-to-value ratios. Using a dataset of securitized subprime mortgages fro- m 2001 to 2006, Demyanyk/Hemert [8] compare the characteristics of different loan vintages in order to iden- tify reasons for the bad performance of mortgages origi- nated in 2006, which triggered the subprime mortgage crisis. Their sample statistics show that the average FICO credit score increased from 620 in 2001 to 655 in the 2006 vintage, which corresponds to the observation that the market expanded in the less risky segment. During the same period average loan size increased from $ 151,000 to $ 259,000 whereas the average loan-to-value (LTV) ratio at origin stayed approximately the same at 80%. Applying a logit regression model to explain de- linquencies and foreclosure rates for the vintage 2006 mortgages, Demyanyk/Hemert [8] identify the low house price appreciation as the main determinant for the bad performance. Also Kiff/Mills [6], who comment on the current crisis, see the slow down in house prices as the main driver for the deterioration in 2006 vintage mort- gage loans. Furthermore they emphasize that although the average subprime borrower credit score increased during the last years, also LTV and debt-to-income ratios increased, which made the mortgages more risky. Gerardi et al. [9] analyse a dataset of homeownership experience in Massachusetts. They find that the 30 day 4 See www.cwbc.com or Chomsisengphet/Pennington-Cross [5] . 5 Kiff/Mills [6] classify a mortgage as subprime if the LTV is above 85% and/or t he debt-to-income ratio exceeds 55% . 3In fact there was a second downgrade wave in the beginning of 2008 on which the authors do not comment. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed 292 delinquency rate shows rather limited variance as it fluc- tuates between 2 and 2.8 % of borrowers. Further, there is no significant correlation to the change in house prices. In contrast, they find a strong negative correlation be- tween foreclosure rates and the house price index over the whole sample period from 1989 to 2007. In particular, Gerardi et al. [9] point out that the house price decline starting in summer 2005 was the driver of rising foreclo- sure rates in 2006 and 2007. These findings show that the house price index drives the portion of delinquent mort- gages that are foreclosed rather than the number of de- linquencies themselves. Estimating cumulative default probabilities they fur- ther find that subprime borrowers default six times as often as prime borrowers. This corresponds to Penning- ton-Cross [10] who also compares the performance of subprime to prime mortgage loans and finds that the lat- ter are six times more likely to default and 1.3 times more likely to prepay. Analysing the determinants of de- fault he concludes that for both - prime and non-prime loans - decreasing house prices as well as increasing unemployment rates increase credit losses. All these empirical studies indicate a strong relation- ship between mortgage loan defaults and house price appreciation in the subprime market. This corresponds to the theoretical literature on mortgage loan default. Ac- cording to option pricing theory a borrower, who is not personally liable, should default when the associated put option is in the money, e.g. when the mortgage debt ex- ceeds the house value. Therefore we will use the house price index as the main determinant of default in our simulation model. 3. Model Set-Up Our analysis is based on a cashflow simulation model. Mortgage loans are more likely to default when they are in “negative equity”, i.e. when the current real estate value is lower than the outstanding debt. This event is usually triggered by a downturn in the house price. Therefore we use a macro factor representing the re- gional house price index as the systematic determinant of default. We assume the regional house price index to have a nationwide and a regional component. The house price at default further determines the loss incurred in a distressed sale following a foreclosure. Payment shocks due to interest rate resets can cause additional foreclosures, especially when house prices have already declined. We account for this by adding a function depending on changes in payment obligations to the idiosyncratic debtor component of our model. 3.1 Simulation Model RMBS are usually backed by mortgage loans from dif- ferent regions. This regional diversification reduces the variance of the repayment distribution of the mortgage portfolio and thereby helps to make the rated tranches less risky. For each region we assume the regional house price index (HPI) to be the main driver of the foreclosure rate. Further, for each region k we decompose the per- centage change of the HPI in year t into an overall posi- tive long-term trend c and a deviation from this trend driven by a nationwide factor Mt and an orthogonal re- gional factor Bk,t : ,k B ktM tk HPIc aM ,t = f (Mt , Mt−1, Bk,t , Bk,t−1 ) (1) Unconditionally, Mt and Bk,t are assumed to be stan- dard normally distributed. Empirical evidence suggests, however, that house price changes display a strong posi- tive autocorrelation6. Therefore we incorporate a first- order autocorrelation of 0.5 for each factor. Thus, condi- tional on Mt−1, Mt has a mean of 0.5· Mt−1 and a standard deviation of 0.75 . The same holds for the regional factors. ρM and ρk account for correlations of house price changes across and within regions. We calibrated the nationwide and regional correlations to ρM = 0.1 and ρk = 0.2 and the scaling factor to a = 0.1. This implies uncon- ditional standard deviations of 5.5% (3.7%) for annual regional (nationwide) house price changes which is in line with empirical evidence7. The unconditional mean annual change of the HPI equals the long-term trend c on both, the regional as well as the national level. For the loans in the underlying mortgage pool we dis- tinguish five debtor groups by credit quality: Prime, Alt-A, Subprime 1, Subprime 2 and Subprime 3. These groups can be interpreted as representing different ranges of the FICO score and further borrower characteristics like payment history and bankruptcies8. The assumed expected default probabilities for the dif- ferent debtor groups and maturities are shown in the cre- dit curves in Table 1 in the appendix. The numbers cor- respond to empirical evidence [9]. In each simulation run a path of annual group migra- tions is computed for each loan in the portfolio. For debtor i located in region k this path depends on a series of latent migration variables Li,k,t , t = 1, . . . , 7. In this respect our simulation model resembles a migration 6In an empirical study based on 15 OECD countries Englund an Ioannidis [11] estimate an average first-order autocorrelation coef- ficient of 0.45 . 7There exist different house price indices for the US. For example, Freddie Mac’s Con ven tional Mortgage Home Price Index (CMHPI- Purchase Only) shows a standard deviation of 3.8% (nationwide) and 5.2% regionally, since 1975. 8There exist no general classification scheme of mortgage loans except for the distinction between Prime, Alt-A and Subprime. Nevertheless it is common to further subdivide the subprime cate- gory into several grades [5] . Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 293 Table 1. Assumed credit curve and one-year migration matrix Panel A: Standard Case Credit Curve t 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Prime 0.20% 0.52% 0.94% 1.47% 2.07% 2.75% 3.50% Alt-A 0.50% 1.11% 1.80% 2.57% 3.41% 4.30% 5.23% Sub1 1.50% 2.98% 4.44% 5.87% 7.29% 8.69% 10.06% Sub2 2.50% 4.88% 7.15% 9.31% 11.36% 13.32% 15.19% Sub3 3.50% 6.71% 9.67% 12.41% 14.94% 17.30% 19.51% Derived One-Year Migration Matrix Debtor Prime Alt-A Sub1 Sub2 Sub3 D Prime 88.0% 6.5% 3.0% 1.5% 0.8% 0.2% Alt-A 9.0% 82.0% 5.0% 2.0% 1.5% 0.5% Sub1 3.0% 6.0% 82.0% 5.0% 2.5% 1.5% Sub2 0.5% 2.5% 6.0% 82.0% 6.5% 2.5% Sub3 0.2% 0.8% 3.0% 7.5% 85.0% 3.5% D 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 100.0% Panel B: Stressed Migration (Due to Interest Rate Step-Up) Stressed One-Year Migration Matrix in t = 3 Rating Prime Alt-A Sub1 Sub2 Sub3 D Prime 88.00% 6.50% 3.00% 1.50% 0.80% 0.20% Alt-A 6.80% 81.51% 6.22% 2.63% 2.08% 0.76% Sub1 0.66% 1.96% 74.44% 10.45% 6.67% 5.82% Sub2 0.07% 0.58% 1.96% 84.44% 14.25% 8.69% Sub3 0.03% 0.15% 0.77% 2.65% 85.13% 11.28% D 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 100.00% Resulting Credit Curve t 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Prime 0.20% 0.52% 0.94% 1.47% 2.07% 2.75% 3.50% Alt-A 0.50% 1.11% 2.81% 3.62% 4.49% 5.41% 6.36% Sub1 1.50% 2.98% 8.29% 9.82% 11.32% 12.78% 14.2% Sub2 2.50% 4.88% 12.67% 14.84% 16.89% 18.83% 20.68% Sub3 3.50% 6.71% 16.36% 19.00% 21.43% 23.69% 25.80% Panel A gives the credit curve for different debtor groups. Each entry in the credit curve describes the aver- age probability of default for a given initial debtor group and maturity t. The numbers are chosen in accor- dance with empirical results (see e.g. Gerardi et al. 2007). The standard one-year migration matrix is sub- sequently matched to this credit curve. Panel B displays our assumed stressed migration matrix for year 3. It is assumed that the interest rate step-up causes significant payment shocks which increase the downgrade probabilities of all non-prime loans in year 3. Even though the migration probabilities in the following years return to the normal level, the expected cumulative default probabilities in every subsequent year are in- creased as shown in the resulting credit curve in Panel B. ,, ,, 11 iktktMkit LHPIc a (2) model for the assessment of collateralized loan obliga- tions where debtors can “migrate” between different rat- ing groups9. with ,it iid 0, 1. At each annual payment date t, we derive the latent variable If the value of the latent variable Li,k,t lies above (be- low) a certain threshold, which corresponds to the quan- tile of the standard normal distribution associated withthe migration probabilities in the so-called migration matrix, the mortgage is upgraded (downgraded) to the respective debtor category. Panel A of Table 1 shows the uncondi- tional expected annual migration probabilities for years 9In general, either migration models or factor models are used to model loan defaults. E.g. in the literature on securitization, Fra- nke/Krahnen [12] simulate rating transitions whereas Hull/White [13] use a one-factor model and Duffie/Garleanu [14] as well as Longstaff/Rajan [15] apply multi-factor models in their analysis. We use a mixture of these two a roac hes.  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed 294 without changes in interest obligations as well as the corresponding multi-year cumulative default probabili- ties. The numbers are chosen to match the empirical findings on prime and subprime default rates of Geradi et al. [9]. Since these numbers are estimated from a time series between 1987 and 2007, they already incorporate the positive long-term trend in house prices. Conse- quently we subtract the long-term trend c from our house price changes such that only the deviation from the ex- pected (positive) long-term growth during the last years enters the latent variable. Due to our assumption of positive autocorrelation in house price changes, our latent variable is not necessarily standard normally distributed, but only normally distrib- uted and the mean depends on the previous realizations. As the thresholds for Li,k,t stay unchanged this yields higher (lower) downward migration and default prob- abilities in years where negative (positive) house price changes are expected10. As can be seen in Equations (2), ρM and ρk also ac- count for correlation of loan defaults across and within regions. Given our calibrated numbers, 30% (= 0.1 + 0.2) of the default risk is due to systematic risk in house price changes and 70% is due to idiosyncratic risks. The idio- syncratic component is given by εi,t, which includes bor- rower specific shocks like unemployment, illness or di- vorce. A payment shock resulting from an increase in interest obligations of a debtor adds to the idiosyncratic risk. We capture this by subtracting a deterministic term from the latent variable in the year of an interest rate step-up. In total, ,, ,, ,,1 11 iktktMk it it iit LHPIc a brr (3) where ri,t denotes the contractual interest rate of loan i in year t. The impact factor bi determines the magnitude of the payment shock and is calibrated for each debtor group separately: We chose bi such that the number of additional defaults due to an interest rate reset matches the forecast made in Cagan [3] for the corresponding percentage interest rate step-up and loan-to-value ratio. In our simulations we assume an interest step-up in year three by 1% for all Alt-A loans and by 2% for all Subprime loans. Together with the impact factors (see Table 3) this implies higher downgrade and also higher default probabilities in year 3 as shown in the stressed one-year migration matrix given in Panel B of Table 1. Applying this stressed migration matrix in the year of the interest rate freeze, significantly increases multi-year default probabilities even though migration probabilities are assumed to return to the ‘normal’ case in the follow- ing years. For simplicity we consider interest only mortgages, i.e. in each year, in which the mortgage stays in one of the five debtor categories, only interest payments are made whereas the total nominal value is due at final maturity11. The interest rate consists of a variable base rate and a spread component. The amount of the spread is deter- mined by the debtor category of the mortgage at the be- ginning of the transaction. In case of default we assume the real estate to be sold in a distress sale with a discount of q percent of the current market value. Given the HPI of date t defined as: H P Ik,0 = 1 , 1 1 t kt k , PI HPI (4) the percentage loss given default of a mortgage in region k at date t is then derived as ,, , 1/ 11 1 ikt ercentageproceed in distressedsale kt LTVatdatet LGD q HPI LTV (5) Thus, we implicitly account for a positive correlation between foreclosure rates and loss given defaults. Due to the definition of our latent variable, a decline in HPI triggers higher default rates and at the same time implies higher loss given defaults. Having derived the annual portfolio cash flows we calculate the sum of discounted cash flows net of trans- action costs (DCn) for each simulation run n: , 1 () 1 Tnt nt tf CF DCPV TC r (6) 10Hence, our migration model implicitly accounts for endogenous migration thresholds whic h is an extension to classical migration models where always standard normally distributed mi gration variables are dra wn. 11According to Ashcraft/Schuermann [4] only about 20 percent o mortgage loans in MBS pools are interest only. Other loans mostly pay annuities, which mainly comprise interest payments in the first years, and may even contain a grace period of two to five years in which only interest is paid. Since we only consider a seven year RMBS transaction, our assumption seems to be reasonable. where C Fn,t denotes the portfolio cash flow at date t and P V (T C ) the present value of annual transaction costs. Dividing this figure by the initial portfolio volume we get a proxy for the relative value of the underlying portfolio. We perform 10,000 simulation runs and determine the Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 295 distribution of this portfolio value as well as several sta- tistics like mean, standard deviation and 99%-quantile. Given the simulated portfolio cash flows at each an- nual payment date we subsequently derive tranche pay- ments. We assume that all losses (interest and principal) are first covered by the excess spread of the transaction, i.e. the difference between the interest income from the underlying portfolio and the interest payments to the rated tranches net of transaction costs, and then by re- ducing the nominal value of the equity tranche. Further, we assume the existence of a reserve account which means that if the excess spread of one period is not wiped out by period losses, the excess cash flow is collected in this account earning the risk-free rate and providing a cushion for future losses12. The holder of the equity tranche does not receive any payments until maturity when he receives the remaining cash flow of the transac- tion. If the equity tranche has been reduced to zero due to previous losses, the face value and subsequently the in- terest claim of the lowest rated tranche is reduced to co- ver the losses. If this tranche claim has already been red- uced to zero, the next tranche is used to cover the losses, etc. 3.2 Sample Transactions Throughout our analysis we consider three illustrative sample portfolios: two subprime mortgage portfolios and one representing the US mortgage market as a whole. The former only include Alt-A and subprime mortgage loans and differ with respect to their regional diversifica- tion. The latter predominantly consist of prime (60%) and Alt-A loans (25%). Five percent each fall in the three subprime classes giving a total subprime share of 15% for the portfolio which roughly resembles the subprime portion in the US mortgage market. The explicit portfolio compositions are given in Table 3 in the appendix. Each mortgage is assumed to pay the risk-free rate, which is assumed to be constant at 4%, plus a spread Table 3. Portfolio characteristics and model assumptions (‘Pacific’) Subprime US Mortgage Market Portfolio Portfolio Portfolio: Initial Volume $ 100,000,000 $ 100,000,000 Number of Mortgages 500 500 initial LTV 90% 90% Share in Region Pacific 20% (40%) 20% New England 20% (40%) 20% North Central 20% (20%) 20% Atlantic 20% (-) 20% South Central 20%(-) 20% Share of Spreads (bps) Prime - 60% 150 Alt-A 20% 25% 225 Subprime 1 30% 5% 300 Subprime 2 30% 5% 350 Subprime 3 20% 5% 400 0 Interest Rate (t = 0) 7.2% 6.0% Interest Rate Step-Up (after 2 Years) Impact Factor (b) Prime 0% 0% 0 Alt-A 1% 1% 15 Subprime 1-3 2% 2% 30 RMBS-Structure: Spreads (bps) Tranches AAA AAA 30 AA AA 50 A A 80 BBB BBB 150 Equity Equity - Transaction Costs 1% p.a. 1% p.a. Maturity 7 years 7 years This table presents the assumed portfolio compositions of our three sample portfolios as well as the assumed tranche structure. The two subprime portfolios only differ in their regional diversification. The regional composition of the ’Pacific’ Subprime portfolio is given in brackets. The depicted spreads are paid in addition to the risk-free rate of 4%. 12According to Ashcraft/Schuermann [4] excess spread is at least captured for the first three to five years of a RMBS deal, which justifies the assum tion of a rese e accoun .  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed 296 ranging between 150 and 400 basis points differentiated by debtor category as shown in Table 3. Further we as- sume that mortgage loans with an initial subprime (Alt-A) rating include an interest rate step-up of 2% (1%) after two years, i.e. all spreads are increased by 200 bps (100 bps) after this initial period13. The long-term trend is house prices is assumed to be c = 3%, the loan-to-value ratio at origin is 90% for each mortgage14 and the dis- count in case of a distressed sale is q = 30%15. Geo- graphically we differentiate five regions16: Pacific, Nor- th Central (including Mountain), South Central, Atlantic (middle and south) and New England. The first subprime portfolio is concentrated in Pacific (40%) and New Eng- land (40%), the regions to perform worst in the crisis, the remaining 20% are North Ventral and Mountain. The other two portfolios are well diversified across all regions. First we simulate payments for the portfolios in the benchmark case, i.e. without any crisis. In year 3 the la- tent variable Li,k,t for each loan is stressed by the impact factor of the current debtor category times the scheduled interest rate step-up which causes an increase in expected cumulative default rates as shown in Panel B of Table 1. Since there is no step-up for prime loans, the expected default rates of these loans stay the same. Columns 3 in Tables 4, 5 and 6 present some statistics describing the port-folios’ repayment distribution. In the benchmark case the expected value of discounted cash flows (net of transaction costs) clearly exceeds the nom- inal value for all three portfolios. The exceedance equals more than two times the standard deviation of discounted cash flows. For the subprime portfolios the average value of the discounted portfolio payment stream after deduct- ing all fees is 113.4% of the initial face value. Since we use the risk-free rate for discounting, this number corre- sponds to a yearly average premium of 1.9% on top of the risk-free rate. The standard deviations over seven years are 5% for the well diversified portfolio and 5.6% for the concentrated one. In case of the representative portfolio the expected discounted value in the benchmark case is 105.5%, yielding an average premium of 0.8% p.a., with a standard deviation of 2.4% over seven years. Subsequently, we simulate payments of three residen- tial mortgage backed security (RMBS) transactions wh- ich are backed by the sample portfolios and have a ma- turity of seven years. We assume that four rated tranches AAA, AA, A and BBB are issued that earn the usual market spreads as shown in Table 3. Additionally, we assume annual transaction costs of 1%, which are paid before any interest payment to the tranches. We calibrate tranche sizes such that their default pro- babilities in the bench-mark scenario are roughly in line with the historical averages given by Standard & Poor’s for the respective rating classes and a seven year maturity. The resulting tranche sizes are also shown in Tables 4, 5 and 617. The calibrated tranche structures correspond to typical RMBS structures observed in the market [4]. As can be seen the AAA tranches is smallest and the equity tranche is highest for the ’Pacific’ subprime portfolio, which is due to a worse regional diversification. 4. Analysis of Mortgage Crisis 4.1 Crisis Scenario Having calibrated our model to the benchmark case we now turn to modeling the crisis scenario. In particular we assume that the sample transaction was set-up two years ago (e.g. second quarter of 2006) with tranche sizes as derived before. The nationwide and regional house price index changes are set to match Freddie Mac’s Conven- tional Mortgage Home Price Index18. In the first year of the transaction, the increase in national house prices slowed down to 2.6%, in the second year there was a downturn of 6%. Regionally, Pacific developed worst with a cumulated two year decrease of 15% in house prices, whereas South Central saw an appreciation of 6%. Table 2 shows all regional trends and the corresponding nationwide and regional macro factors. Figure 1 shows 13This step-up is assumed to be fixed at loan origination and is inde- pendent of possible downward migrations until the reset date. 14Gerardi et al. [9] report a mean LTV ratio of 83% and a median o 90% in the last three years. 15Pennington-Cross [16] provides a survey study on the discount in case of a distressed sale and finds that foreclosed property appreci- ates on average 22% less than the area average appreciation rate. Given that foreclosures also lead to additional costs, we will assume a discount of 30% on the current market value in our simulation analysis. Cagan [3] also states that foreclosure discounts of 30% are quite usual. 16We followed the regions defined in Freddie Mac’s Conventional Mortgage Home Price Index but pooled some neighbouring regions. 17A slightly different tranche structure would arise when using the expected loss rating from Moody’s. But it should be noted that tranches with the same rating have nearly the same expected losses in our benchmark case. 18Our reference index is the ’ urchase onl ’ index. Figure 1. Expected HPI for different scenarios This figure shows the expected development of the House Price Index (HPI) averaged over our five regions for different simulation scenarios: In the benchmark case a long-term house price growth of 3% p.a. is assumed. The crisis scenario is set by fixing macrofactor realisations in the first two years (see Table 1) which cause a severe decline in house prices. Departing from this crisis scenario the positive feedback sce- nario assumes that there is no autocorrelation between years 2 and 3, such that house prices recover faster from the crisis. The scenarios Robustness 1 and 2 assume a weaker house price stabilization as the utocorrelation is only reduced by a half or one fourth, respectively. a Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed297 Table 2. Definition of the crisis scenario Region Year 1 Year 2 H P I 1 H P I 2 µ 3 E (∆ H P I 3 ) E [ H P I 3 ] US-Av erage M -0.19 -2.80 1.03 0.96 -1.4 -1.2% 0.95 Pacific B 1 0.13 -2.60 1.03 0.85 -1.3 -7.2% 0.79 New England B 2 -0.76 0.18 0.99 0.94 0.09 -1.0% 0.93 N. Cen tral B 3 -0.09 0.43 1.02 0.98 0.22 -0.5% 0.98 Atlantic B 4 0.13 0.44 1.03 0.99 0.22 -0.4% 0.99 S. Cen tral B 5 0.58 1.52 1.05 1.06 0.76 2.0% 1.08 Columns 3 and 4 depict the assumed nationwide and regional factor realisations in year 1 and 2. Columns 5 and 6 give the corresponding regional HPI after one and two years. The last three columns show the mean of the distribution for the third year, the corresponding expected change in re- gional house prices and the corresponding expected HPI after three years according to our modeling assumptions. Figure 2. Distribution of discounted cashflow s This figure shows the distributions of discounted cash flows (in percent of initial portfolio volume) for all three portfolios (‘Pacific’ Subprime Portfo- lio, Subprime Portfolio, US mortgage market Portfolio) and four different simulation scenarios. the expected average house price development over seven years that is implied by the realisations of the first two years and our modelling assumptions. Given these macro-factor values in the first two years, we again simulate portfolio cash flows and tranche pay- ments. Due to the positive autocorrelation, the negative trend (as well as the positive trend) in regional house price indices affect the realisations of the latent variable in the following years. For illustration the mean of the macro factors for the third year as well as the corre- sponding expected cumulative HPI up to year 3 are shown in Table 2. For the three portfolio settings the resulting portfolio and tranche characteristics given this crisis scenario are depicted in Tables 4 to 6. The crisis leads to a sharp drop in the expected level of the national house price index after seven years from 1.23 to 1.03 (appr. 16%) which translates into significantly lower discounted cash flows. In fact, our simulation results show that the house price index and the portfolio cash flows are positively corre- lated with 0.8. Whereas the expected discounted cash flow of the diversified subprime portfolios stays above the nominal issuance volume, the expected discounted cash flow of the US mortgage market portfolio drops roughly to $ 100 million indicating that there is no pre- mium left for originator. The ‘Pacific’ subprime portfolio concentrated in the Pacific, New England and North Central region shows a drop to less than $ 96 million, a severe loss. Obviously, the crisis causes a severe first order stochastic dominance deterioration in the distribu- tions of discounted cash flows of all three portfolios as depicted in Figure 2. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed 298 The shift in the distribution of discounted cash flows causes all tranches to exhibit much higher default prob- abilities and expected losses such that it would be neces- sary to downgrade them several rating notches. For ex- ample the AAA tranche of the diversified subprime port- folio would now receive an (A-) rating and the most jun- ior tranches would only get a (B-) rating. The effect of the crisis on the tranches’ risk characteristics is even slightly stronger for the US mortgage market portfolio. Here the default probabilities and expected losses are roughly ten times higher than before whereas for the di- versified subprime portfolio the numbers only increase by a factor of about eight. Of course, the effect is largest for the Pacific subprime portfolio with default probabili- ties increasing by 30 times and the most junior tranche being certain to default. The main part of the decrease in expected payments is allocated to the equity tranche. Looking at the diversified subprime portfolio, the expected present value of equity tranche payments decreases by $ 9.2 million, 92% of the total portfolio decrease of $ 10 million. For the US port- folio the situation is similar. The expected discounted cashflow to the equity tranche decreases by $ 4.2 million - about 80% of the total portfolio decrease. Nevertheless the decline in expected discounted portfolio cashflows is rather moderate, only 10% for the subprime portfolio and 5% for the US mortgage market portfolio. This is due to the fact that both portfolios are assumed to be well diver- sified concerning the regional allocation with some re- gions still displaying a positive house price trend. In con- trast, the Pacific subprime portfolio concentrated in re- gions performing poorly decreases by nearly 18% in ex- pected discounted cash flow. Here, the equity tranche bears only 71% of this decline as the rated tranches are hit more heavily. Curiously, the equity tranche still has a positive expected cash flow of $ 1.3 million, even though the lowest rated tranche is always hit by losses. This is due to excess spread collected in later years. Fewer ex- cess spread would accrue in case of an interest rate freeze. 4.2 The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze Starting from the crisis scenario described in the previous subsection we now analyse the effects of an interest rate freeze on the sample RMBS. In particular, we assume that the interest step-up after two years is cancelled such that all mortgage loans continue to pay the low initial rates. The direct effect of this freeze will be twofold. On the one hand, lower interest rates reduce the portfolio payment claims and, thus, negatively affect payments to the issued tranches. On the other hand, an interest rate freeze takes pressure from borrowers such that there will be less foreclosures which in turn lowers the foreclosure costs. We study this trade-off of direct effects first. In the second part of this section we investigate dif- ferent scenarios of house price reactions following the freeze. In fact, the lower number of foreclosures may have a positive feedback effect on house prices. We find that a relatively moderate stabilization of house prices renders the net effect on most tranches positive. 4.2.1 Pure Interest Rate Freeze As noted before, the interest rate freeze does not only lead to less interest payments from the portfolio, but has also a positive effect on the portfolio default rate. In par- ticular, there are less downward migrations and also less defaults in year three because the stress component of all Alt-A and subprime debtors disappears (see Equation 2) due to unchanged payment obligations. In effect, by avoiding downgrades the interest rate freeze does not only decrease default rates after three years but also re- sults in lower cumulative default probabilities in subse- quent years. We simulate portfolio repayments and tranche charac- teristics for this scenario. The results are shown in Figure 2 and Tables 4 to 6. Although the interest rate freeze lowers the default rate of the underlying portfolio, this does not compensate for the decline in interest payments from years three to seven. Thus, the freeze leads to a de- terioration in the distributions of discounted cashflows. For the US mortgage market portfolio we see a first order stochastic dominance deterioration with the expected discounted portfolio cashflow being further reduced by $ 1 million. Also all RMBS tranches deteriorate as com- pared to the crisis scenario. The former AAA tranche which would have to be downgraded to BBB+ due to the crisis would now only receive a BBB rating. Again a substantial share of the additional loss is allocated to the equity tranche (appr. 87%). For the diversified subprime portfolio we see an addi- tional loss of $ 2.2 million due to the interest rate freeze and a second-order stochastic dominance deterioration in the distribution. In fact, lower quantiles slightly improve as compared to the crisis scenario. Consequently, the senior tranche benefits from the interest rate freeze whereas all other RMBS tranches suffer additional losses. Here the equity tranche takes 69% of the additional ex- pected loss. Concerning the ’Pacific’ subprime portfolio the additional expected loss is only $ 0.8 million. As the regions represented in this portfolio saw the steepest downturn in house prices bringing many debtors close to default, waiving interest claims will avoid most foreclo- sures such that the positive effect of a rate-freeze is strongest in this case as compare to the other portfolios. Again we see a second-order stochastic dominance shift in the expected discounted cashflow distribution leaving the senior tranche better off at the expense of lower rated tranches and the equity piece. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 299  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed 300 Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed301 Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 302 4.2.2 Inter est R ate Fr eeze and Posi tive Fee dback E ffect As shown in the previous subsection, the first round ef- fects of an interest rate freeze are not sufficient to attenu- ate the crisis. Yet a decrease in foreclosure rates may take pressure off the housing market such that the negative trend in the regional house prices is mitigated19. This in turn will lead to a positive effect on subsequent foreclo- sure rates. In the previous scenarios, persistent trends in the house price index are implemented by positive autocorrelation in the house price index. Therefore the downturn in years one and two leads to an expected downturn in year three, i.e. the conditional mean of the variable describing changes in the house price index is negative. Combined with the regional components, this yields expected house price changes of between -7.2% and 2.0% for the respec- tive regions, nationwide -1.2% (see Table 2) which is substantially below the long-term mean of 3%. We now assume these negative trends to be stopped by the interest intervention. In effect, expected house price apprecia- tions rise to the long-term trend of 3% for region 1 (Pa- cific) and up to 6.4% for region 5 (South Central) in year 3. We implement this by excluding the autocorrelation effects from year two to year three in the nationwide factor as well as in all regions with negative factor re- alization in year 2. In total, the average HPI stabilizes by four percent in year three. Feedback effects in subsequent years result in an average HPI that by the end of year seven is appr. 11 percent higher than in the crisis scenario, as shown in Figure 1. The results for the portfolios are displayed in Figure 2 and Tables 4 to 6. For both subprime portfolios the expected discounted cashflow exceeds the value in the crisis scenario without an interest rate freeze. Comparing the cumulative ex- pected discounted cash flow distributions this positive feedback scenario second-order stochastically dominates the crisis scenario with all lower quantiles being substan- tially improved. Consequently, all rated RMBS tranches benefit concerning their default probabilities and also their expected losses. Given the diversified subprime portfolio the AAA and the AA tranche perform as well as in the benchmark scenario without crisis meaning that no downgrade would be necessary. The costs of the interest rate freeze are completely borne by the owner of the eq- uity tranche. The US mortgage market portfolio loses less interest payments due to the interest rate freeze as prime mort- gage loans representing 60% of the portfolio do not in- corporate an interest step-up. Here, the positive effect of stopping the house price decline overcompensates the foregone interest resulting in higher expected discounted cash flow compared to the crisis scenario. All tranches including the equity tranche profit with higher tranches benefiting most. This is due to a more narrow distribution of losses. Compared to the crisis we again observe a second order stochastic dominance shift in cumulative repayments. Summarizing, our results indicate that an interest rate freeze may help to alleviate the current crisis. Even though RMBS tranche investors lose a significant portion of their loss protection, this deterioration may be over- compensated by improvements in mortgage payments due to lower foreclosure rates and a positive feedback effect in the housing market. For all three portfolios we derive positive net effects on all rated RMBS tranches as compared to the crisis scenario. The higher the tranche, the more it improves. Especially, the AAA tranche bene- fits from the rate freeze. Thus, the RMBS market will benefit from an interest rate freeze which can induce positive spill over effects on other markets. In particular, markets for other structured instruments containing RMBS tranches may stabilize. Especially, special in- vestment vehicles backing their commercial paper fund- ing with senior RMBS tranches may recover. 4.3 Robustness Checks 1) Assumptions concerning House Price Developments Our previous results depend on several assumptions concerning house price developments which are moti- vated by empirical findings. We set the crisis scenario to match house price developments in the main US regions during the last two years. When discussing the positive feedback effect of an interest rate freeze we had to make a specific assumption concerning house price stabiliza- tion. Naturally, other house price reactions are also pos- sible. As robustness checks we derive portfolio and tranche repayments for less favorable assumptions concerning house price stabilization. In particular we assume the negative house price trend only to be partially offset by the interest rate freeze. Instead of zero autocorrelation in year three increasing the average house price index by four percent compared to the crisis situation, we now assume that only half (one fourth) of this effect is real- ised. Figure 1 shows the expected average house price development for these two scenarios. Tables 4 to 6 dis- play the tranche and portfolio characteristics for these additional scenarios. As can be seen, a more moderate stabilization of two percent in year three (translating into 5.5 percentage points until year seven) is sufficient to substantially im- prove all rated RMBS tranches (see Robustness 1 ). Even a stabilization of only one percent in year three (incresing to 2.7 percent in year seven) leaves the rated tranches slightly better off than in the crisis scenario (see Robust- ness 2 ). 19Cagan [3] finds significant additional foreclosure discounts in re- gions with high foreclosure rates. This indicates limited buyer ca- pacities unable to absorb the excess supply without additional dis- counts.  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed303 Given these results we conclude that the qualitative results are quite stable towards changes in the assump- tion of house price stabilization: Due to lower excess spread, the payments to the equity tranche will be re- duced the most and due to lower probabilities of high losses the highest rated tranche will profit most from an interest rate freeze. Even for modest house price reac- tions the net effect of the freeze is positive. 2) Assumptions concerning RMBS-Structure A further assumption which needs to be critically re- viewed is our assumption concerning the payment wa- terfall for our RMBS tranches. In the previous simula- tions we always assumed the existence of an unlimited reserve account, which means that the holder of the eq- uity tranche only receives payments at final maturity and that at each annual payment dates all excess cash flows are placed in an extra account which can be used to cover future losses. In fact other reserve account specifications are possible, e.g. a capped reserve account, where all excess cash flows above this cap are paid out to the holder of the equity piece periodically, or even a structure without any reserve account, in which the holder of the equity tranche receives all excess cash flow at each pay- ment date. This assumption mainly influences the calibration of tranche sizes in the benchmark case. In particular, a structure without a reserve account will lead to a much smaller AAA tranche a bigger equity tranche. In this case the effect of the interest rate freeze is less pronounced since the tranche sizes are already calibrated to provide a better protection against interest losses. Nevertheless, the qualitative effects stay the same with the difference that now an even more moderate house price stabilization is sufficient to make all rated tranches better off than in the pure crisis scenario. 4.4 Other Policy Options 1) Interest rate cuts Throughout the paper we assumed that the risk-free interest rate on top of which credit spreads are paid stays the same over seven years. In fact the crisis might lead to a cut in this reference rate. Looking at the repayments of the mortgage loans analysed in this paper lowering the reference rate would have a positive effect. Thus, interest rate cuts are an additional policy option worth examining. However, discussing the macroeconomic consequences of interest rate cuts is beyond the scope of this paper. 2) Housing Bill For mortgage debtors the effects of the proposed in- terest rate freeze are comparable to the sought impact of the Housing Bill of July 2008. Here, state guarantees help troubled borrowers to refinance at lower rates. The key difference between the two policy options is on the lender side. With the interest rate freeze, mortgage banks and equity tranche holders bear the potential costs. Looking at a portfolio of mortgage loans the state guar- antee included in the Housing Bill adds a large state owned first loss position, irrespective of the portfolio being securitized. Compared to our simulation results above, lenders, all rated tranches and especially the eq- uity tranche would profit at the tax payers expense. 5. Conclusions The discussed interest rate moratorium for subprime mortgages is one option to tackle the current crisis. It is an agreement between two parties - the U.S. government and the originating banks - that affects two different third parties: the mortgage debtors and investors in RMBS tranches. The first group will unambiguously profit from an interest rate freeze. Some of their payment obligations are waived, thus they might avoid default. Additionally, they benefit from a stabilizing housing market. The effect on RMBS-tranches is more ambiguous. First, we show that the pure interest rate freeze decreases the portfolio payment stream’s expected value by one to 2.2 percent, depending on portfolio composition. The vast majority of this decrease is borne by the equity tranche. Default probability and expected loss of rated tranches only slightly deteriorate as compared to the cri- sis scenario with senior tranches even being better off. Second, we take into account that the interest rate freeze may have a positive second round effect as a reduction in foreclosures takes pressure off the housing market. In this case we find that already a very moderate mitigation of the house price downturn yields a positive net effect on all rated tranches. A stabilization of one percent in year three leaves all tranches in each of our three sample transactions better off (compared to the crisis scenario without policy reaction). For the holder of the equity tranche, the situation is different. Looking at the average of the three sample RMBS a four percent stabilization in house prices is needed for him to slightly benefit from the interest rate freeze. Thus, should the US government and loan and savings associations decide on an interest moratorium on adjustable rate subprime mortgages, this would probably not come at the expense of the RMBS investors as a third party. If additional losses occur they are borne by originators and equity tranche investors. As these parties are the ones in charge of the criticized lend- ing standards we argue that reconsidering this policy op- tion is worth wile. REFERENCES [1] International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report, Washington DC, April 2008. [2] Keys, J. Benjamin, T. Mukherjee, A. Seru, and V. Vig, “Did securitization lead to lax screening? Evidence from Subprime Loans,” Working Paper, 2008. [3] Cagan, L. Christopher, “Mortgage payment reset: The issue Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  How to React to the Subprime Crisis? - The Impact of an Interest Rate Freeze on Residential Mortgage Backed Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 304 and impact,” First American CoreLogic, March 19, 2007. [4] Ashcraft, B. Adam, and T. Schuermann, “Understanding the securitization of subprime mortgage credit,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, No. 318, 2008. [5] Chomsisengphet, Souphala and A. Pennington-Cross, “The evolution of the subprime mortgage market,” Fed- eral Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Vol. 88, No. 1, pp. 31–56, 2006. [6] Kiff, John and P. Mills, “Money for nothing and checks for free: Recent developments in U.S. subprime mortgage markets,” Working Paper, International Monetary Fund, 07/188, 2007. [7] G. Dell’ Ariccia, D. Igan, and L. Laeven, “Credit booms and lending standards: Evidence from the subprime mortgage market,” Working Paper, 2008. [8] Demyanyk, Yuliya and Otto Van Hemert, “Understanding the subprime mortgage crisis,” Working Paper FRB St. Louis and NYU Stern, 2007. [9] Gerardi, Kristofer, A. H. Shapiro and P. S. Willen: “Sub- prime outcomes: Risky mortgages, homeownership ex- periences, and foreclosures,” Working Paper Federal Re- serve Bank of Boston, No. 07–15, 2007. [10] Pennington-Cross, Anthony “Credit history and the per- formance of prime and nonprime mortgages,” Journal of Real Estate Research, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 279–301, 2003.. [11] Englund, Peter and Y. M. Ioannidis, “House Price Dy- namics: An International Empirical Perspective,” Journal of Housing Economics, Vol. 6, pp. 119–136, 1997. [12] Franke, Günter and Krahnen, Jan Pieter: “Default risk sharing between banks and markets: The contribution of collateralized loan obligations,” in: The Risks of Finan- cial Institutions, NBER book edited by Mark Carey and Rene Stulz, University of Chicago Press, pp. 603–631. 2006. [13] Hull, John, and A. White: “Valuation of a CDO and an nth to Default CDS without monte carlo simulation,” Journal of Derivatives, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 8–23, 2004. [14] Duffie, Darrell, and N. Garleanu: “Risk and valuation of collateralized debt obligations,” Financial Analysts Jour- nal (January/February), pp. 41–59, 2001. [15] Longstaff, A. Francis, and A. Rajan, “An empirical analy- sis of the pricing of collateralized debt obligations,” Jour- nal of Finance, Vol. 63, No. 2, pp. 529–563, 2008. [16] Pennington-Cross, Anthony, “The value of foreclosed property,” Journal of Real Estate Research, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 193–214, 2004.

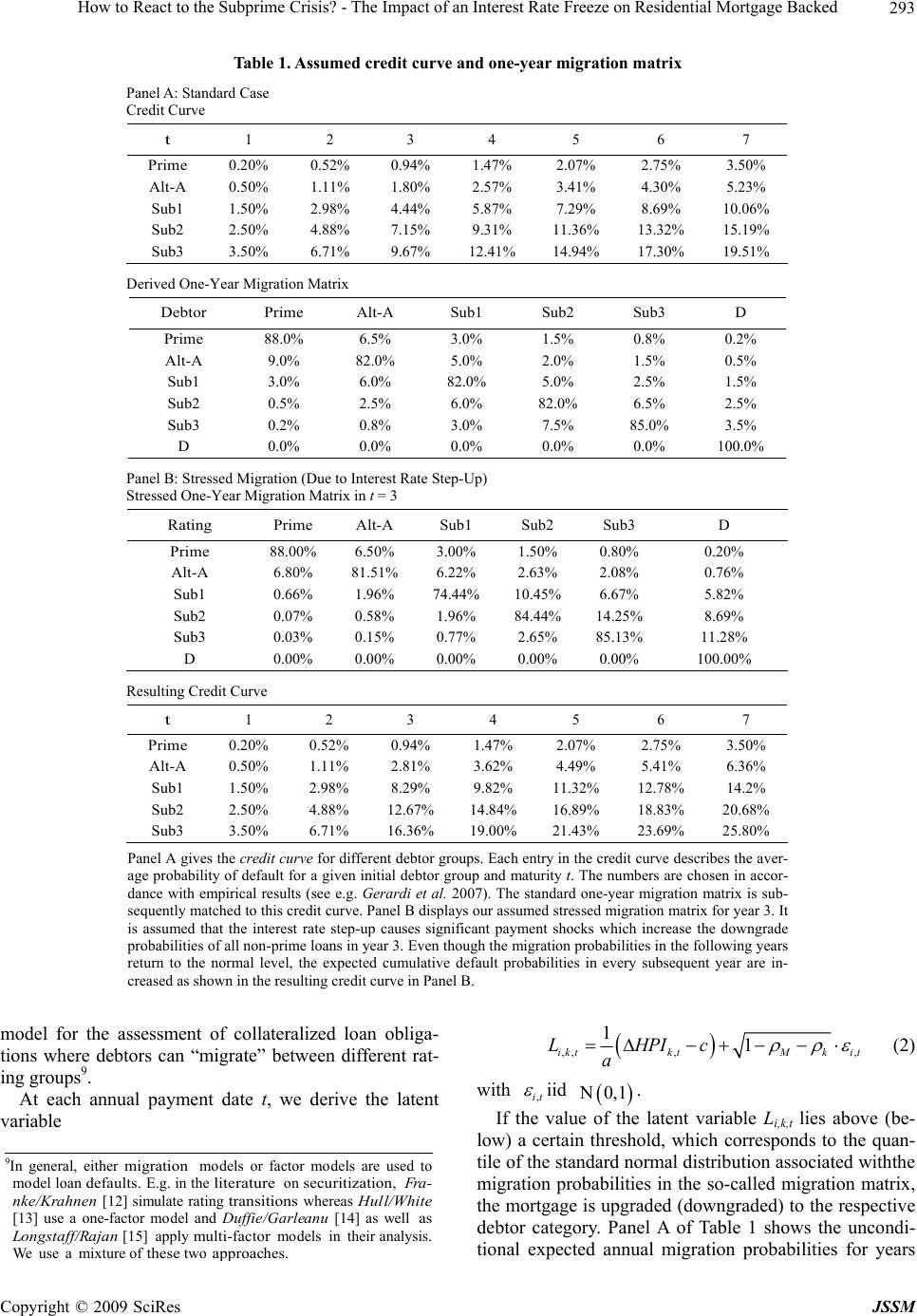

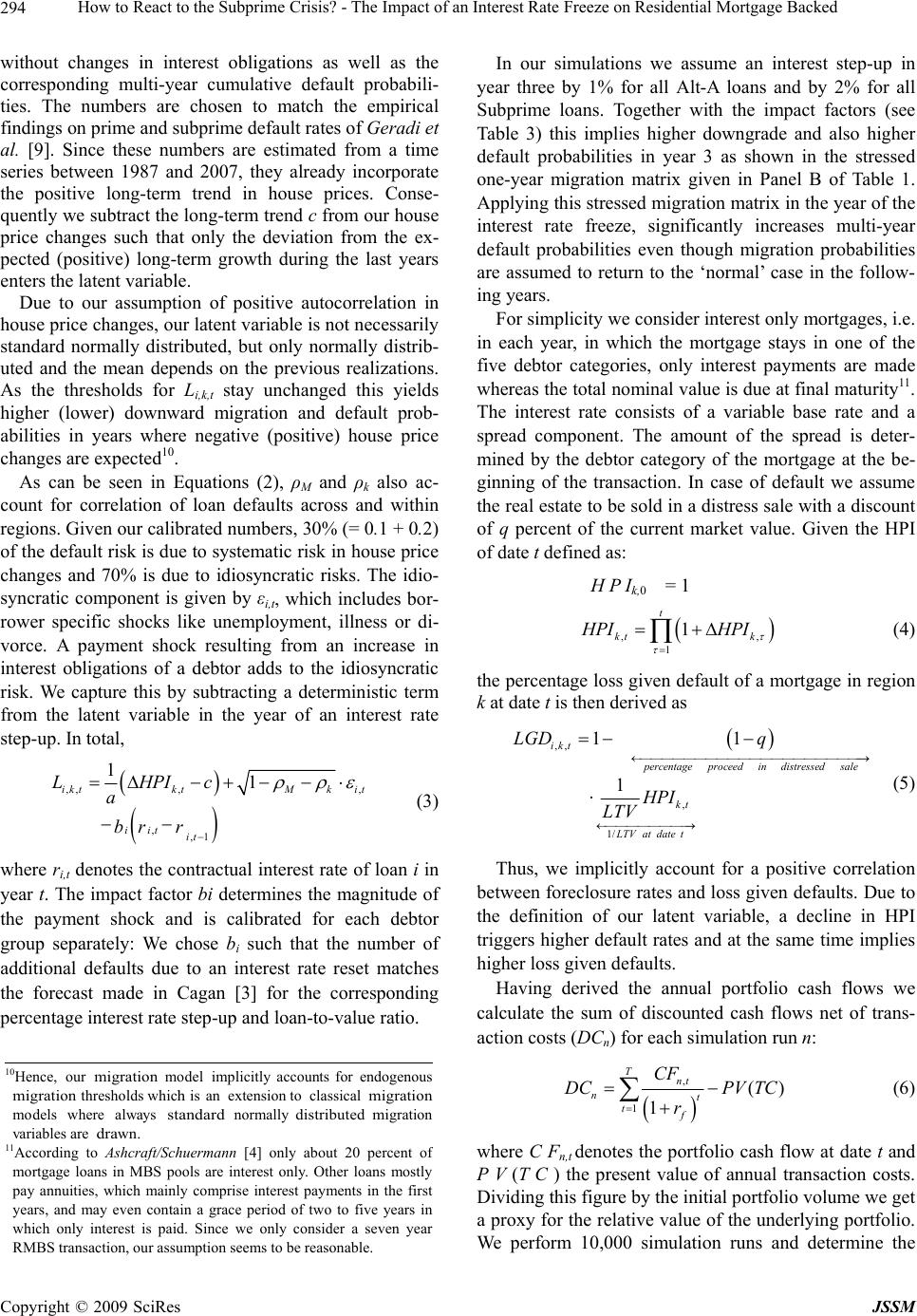

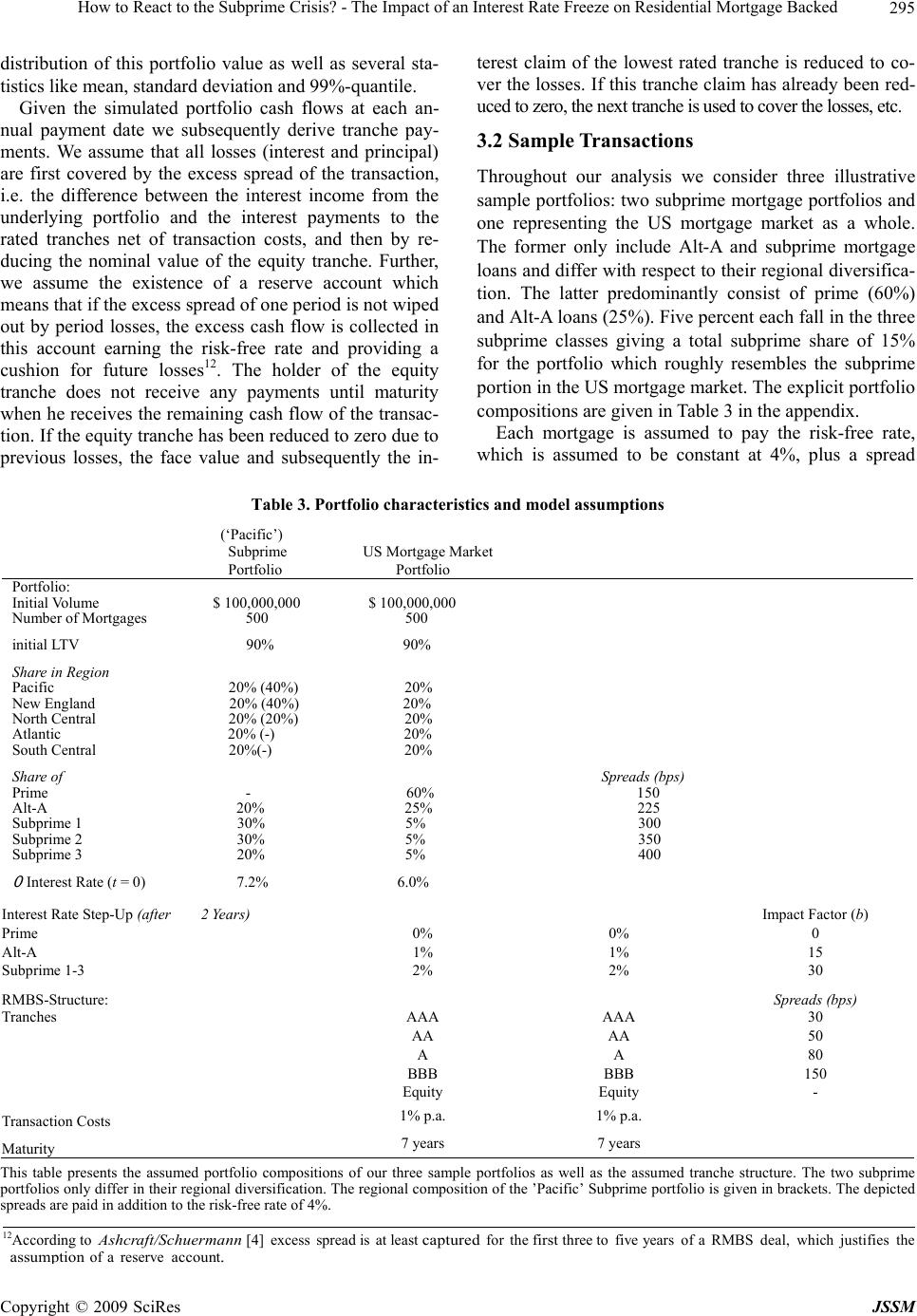

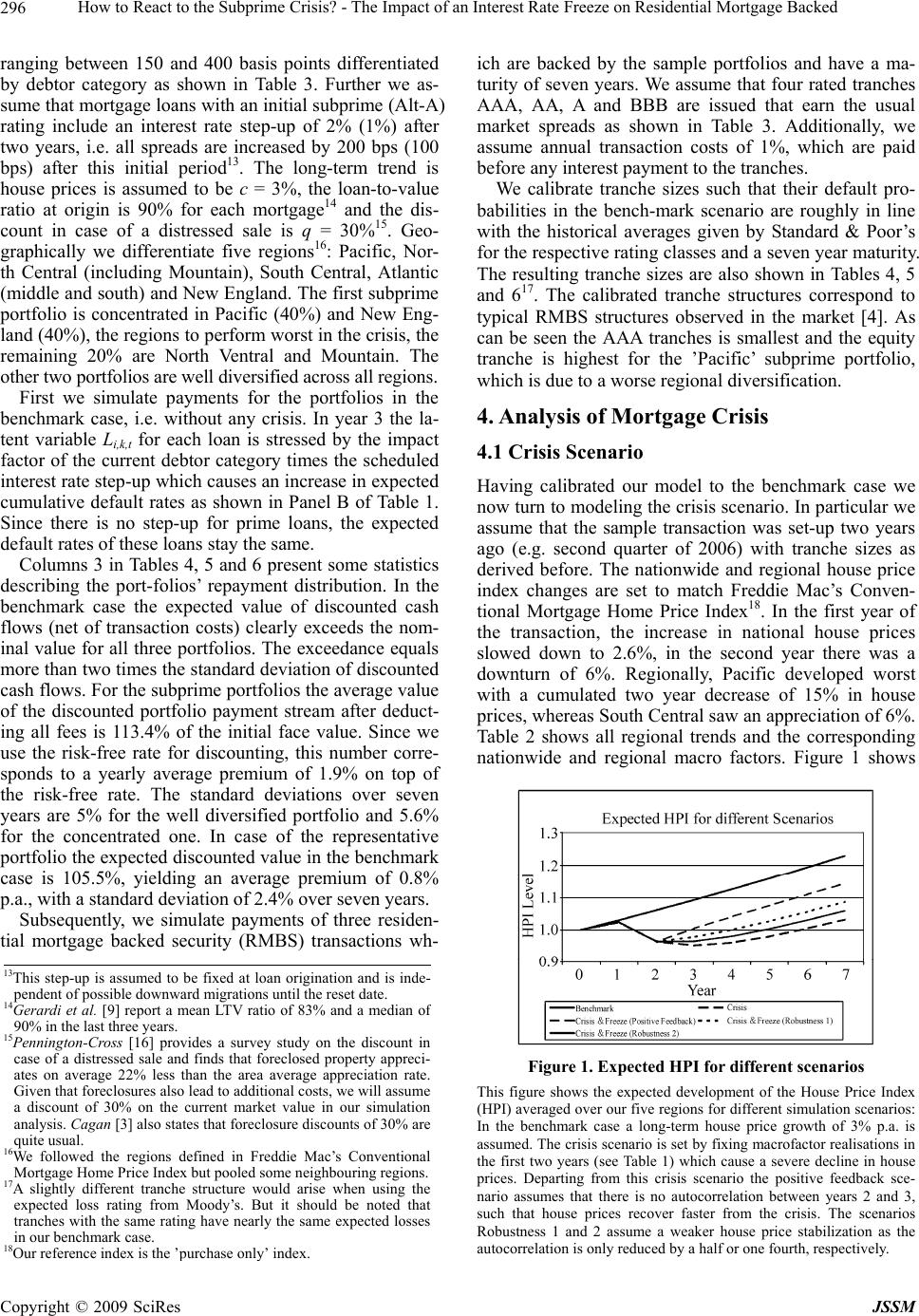

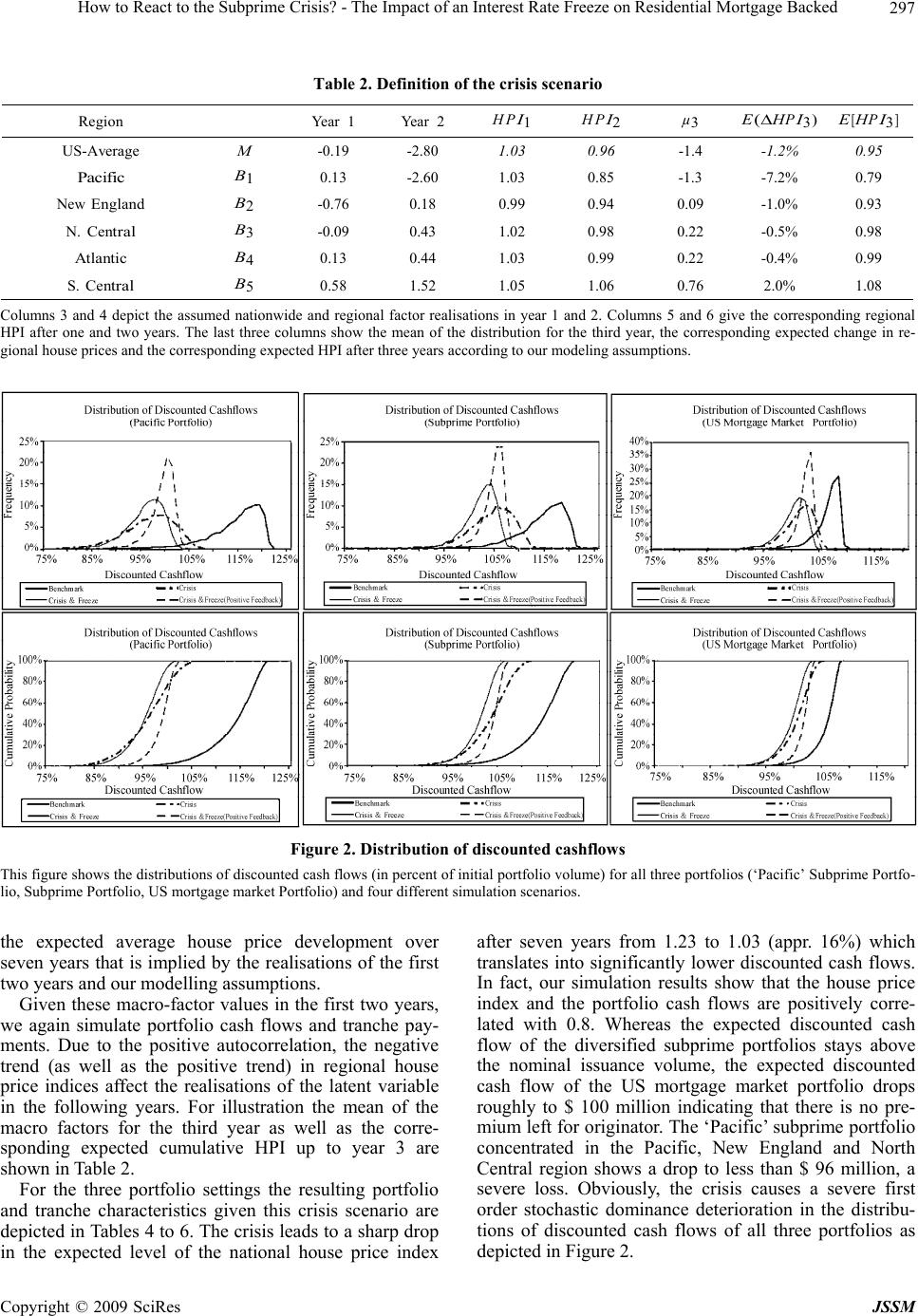

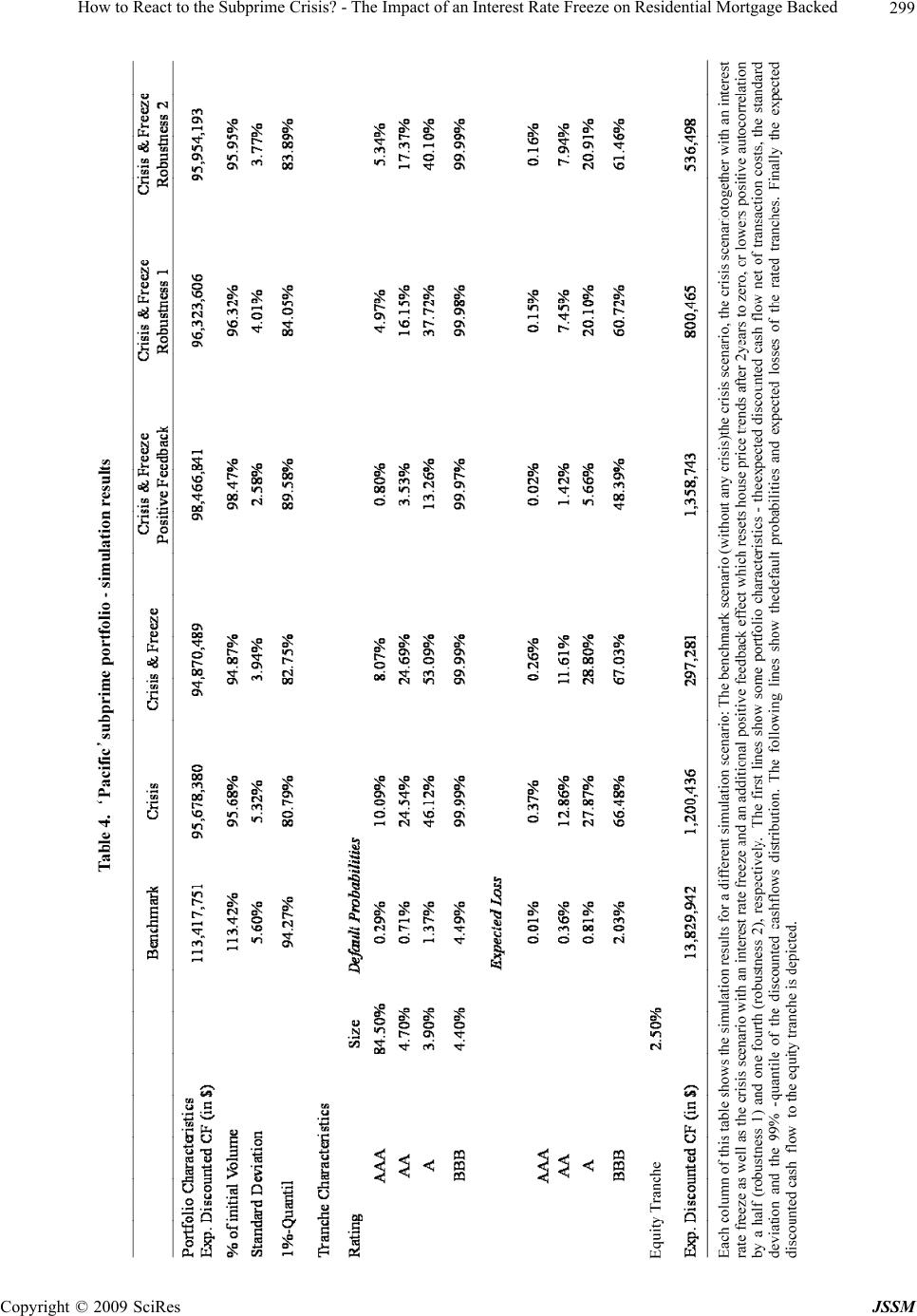

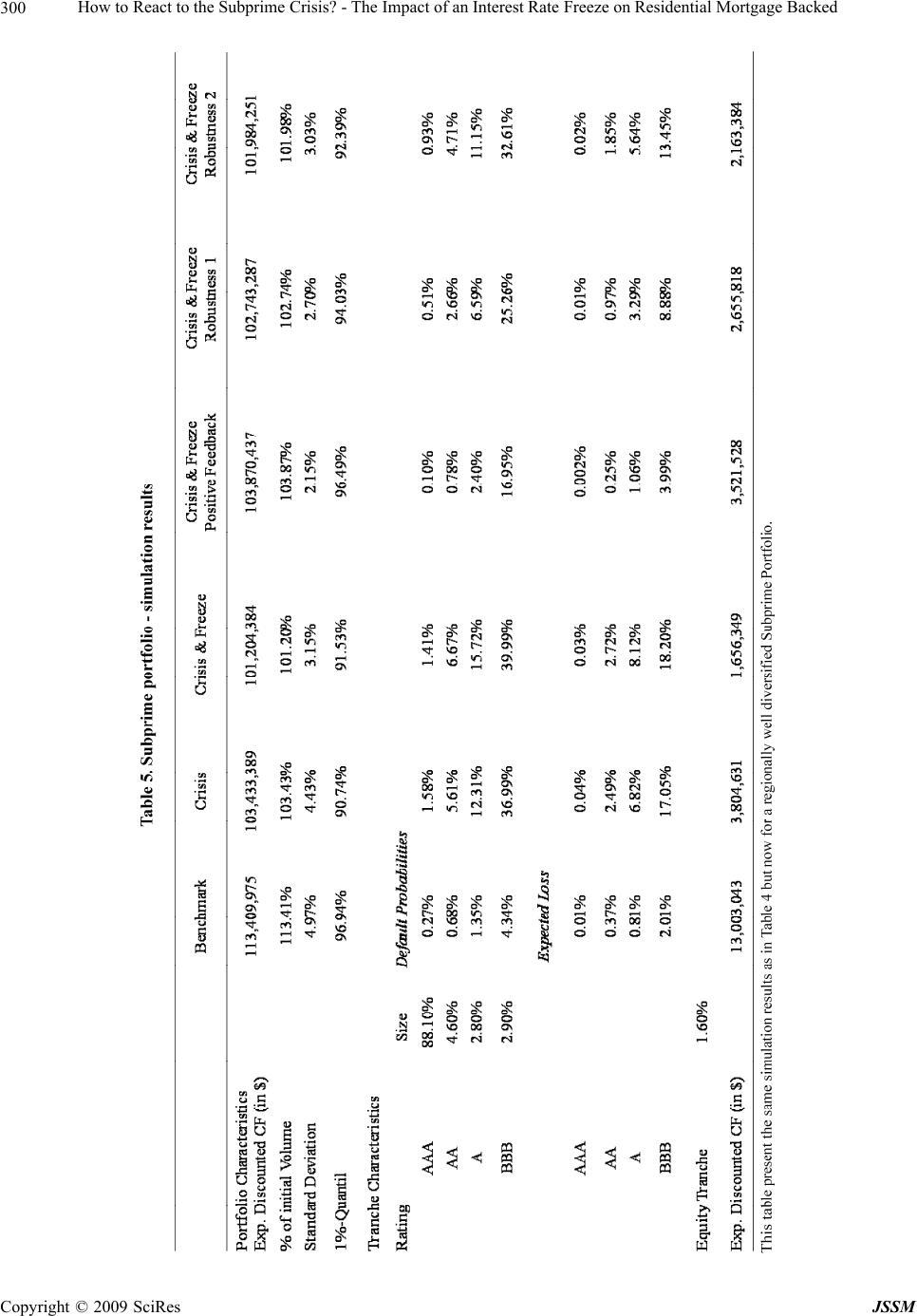

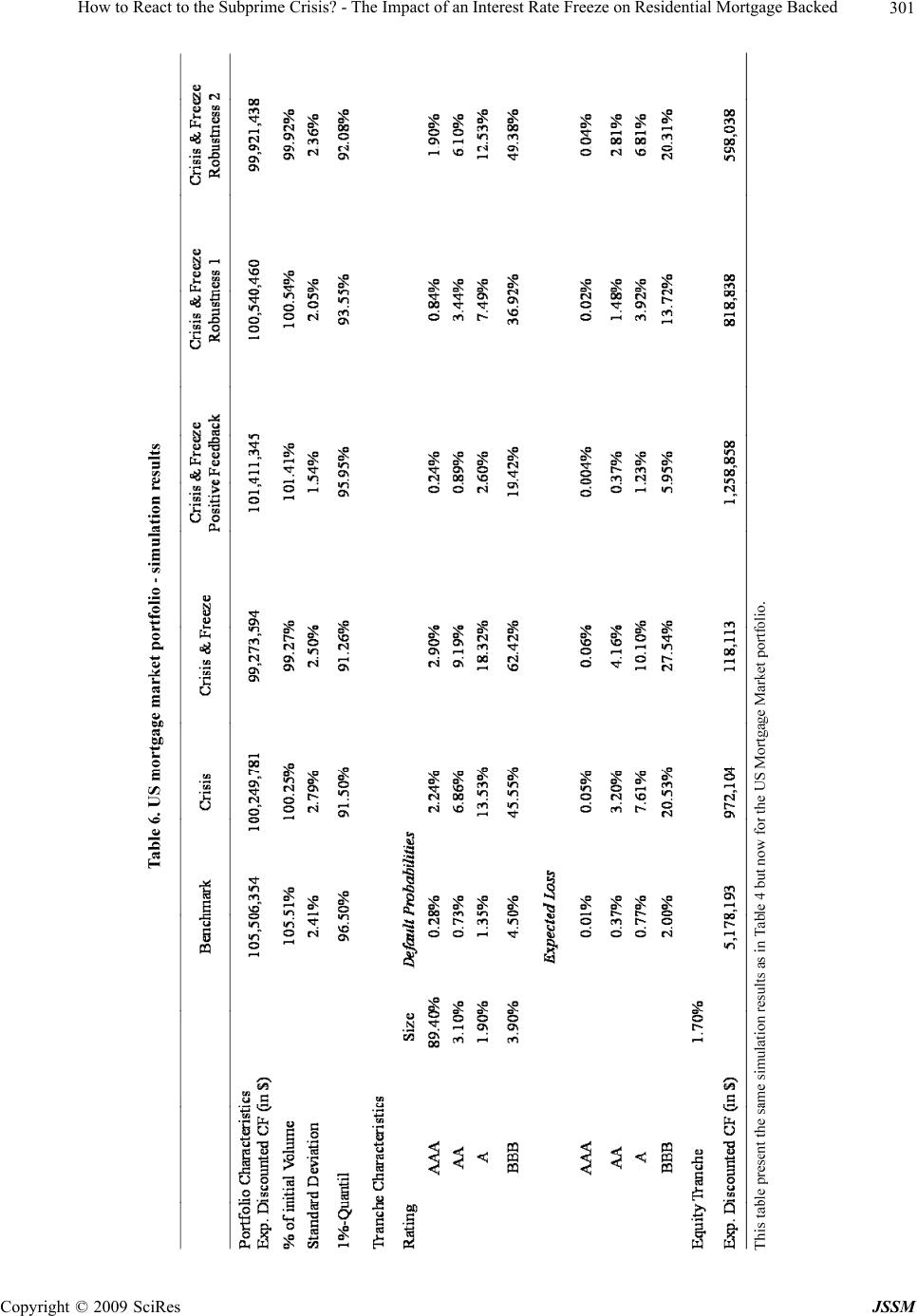

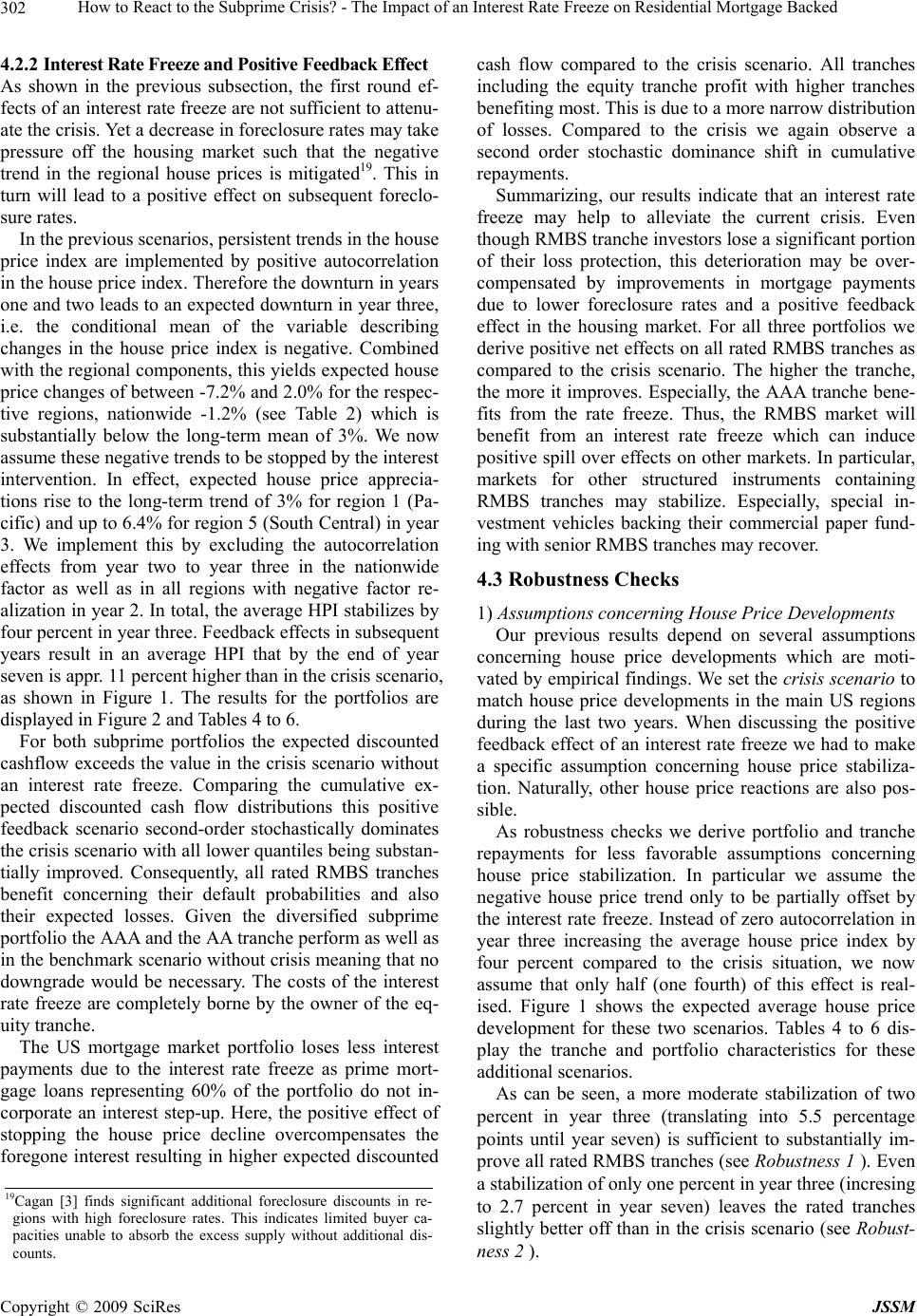

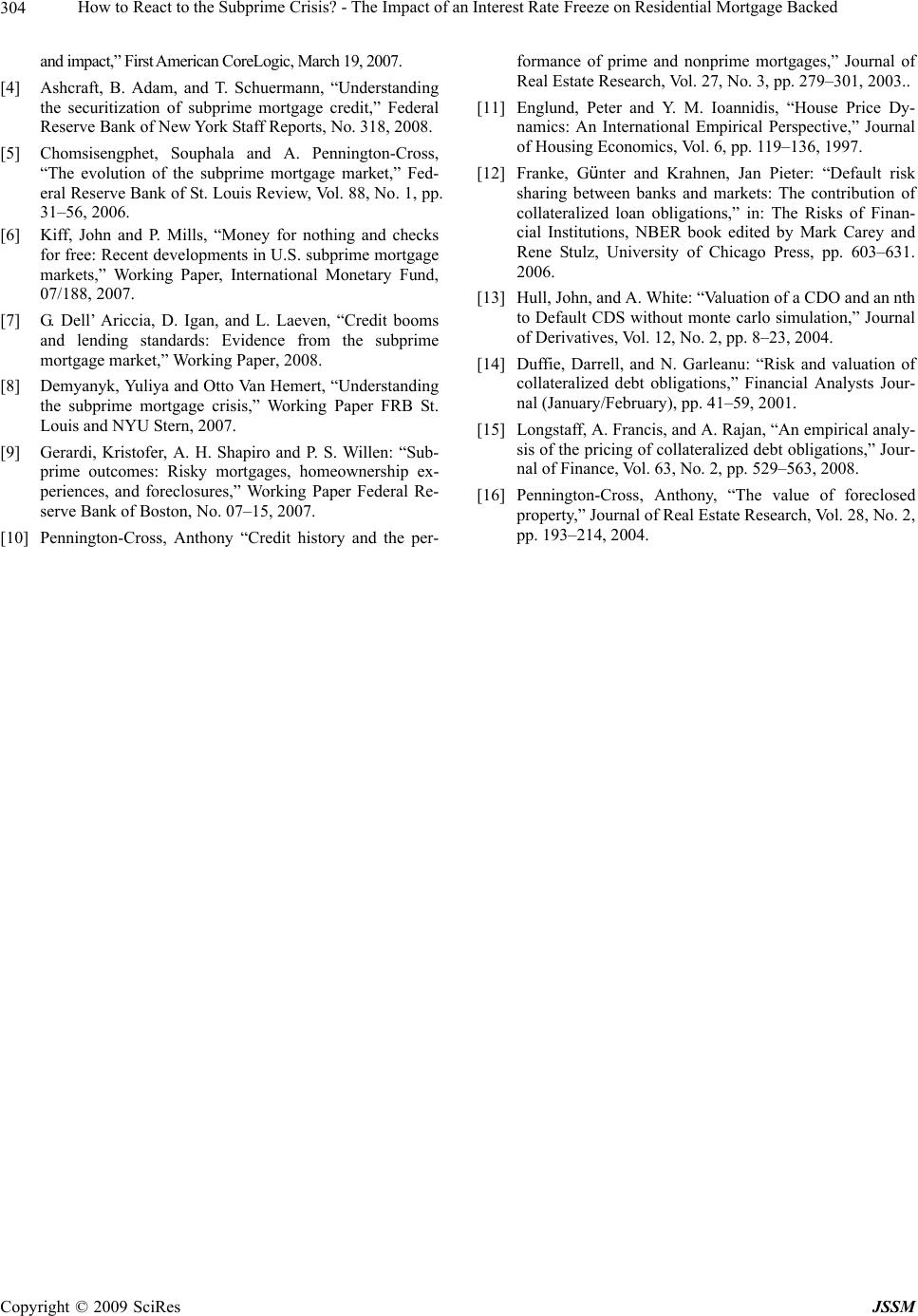

|