Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2011. Vol.1, No.2, 24-32 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/ojml.2011.12004 Effects of Word Order Alternation on the Sentence Processing of Sinhalese Written and Spoken Forms Katsuo Tamaoka1, Prabath Buddhika Arachchige Kanduboda1, Hiromu Sakai2 1Graduate School of Languages and Cultures, Nagoya University, Aichi, Japan; 2Graduate School of Education, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan. Email: ktamaoka@lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp Received September 22nd, 2011; revised November 19th, 2011; accepted November 27th, 2011. In both written and spoken forms, the Sinhalese language allows all six possible word orders for active sentences with transitive verbs (i.e., SOV, OSV, SVO, OVS, VSO, and VOS), even though its unmarked order is sub- ject-object-verb (SOV) (e.g., Gair, 1998; Miyagishi, 2003; Yamamoto, 2003). Reaction times for sentence cor- rectness decisions showed SOV < SVO = OVS = OSV = VSO = VOS for the written form, and SOV < SVO = OVS < OSV = VSO = VOS for the spoken form. The different degrees of reaction times may correspond to the three different types of word order alternation. First, the fastest reaction time for SOV word order corresponds to the canonical order SOV without any structural change, represented as [TP S [VP O V] ] for both the written and spoken forms. Second, word order alternation at the same structural level is involved in both SVO and OVS, [TP S [VP t1 V O1] ] for SVO and [TP t1 [VP O V ] S1 ] for OVS, resulting in a slower reaction speed than SOV. Third, and again for only the spoken form, word order alternation takes place at a different structural level, [TP’ O1 [TP S [VP t1 V ] ] ] for OSV, [TP’ V1 [TP S [VP O t1] ] ] for VSO, and double word order alternations take place within the same level as [TP t1 [VP t2 V O2] S1] for VOS. These word order alternations for OSV, VSO and VOS require an extra cognitive load for sentence processing, even heavier than for a single word order alternation of SVO and OVS taking place at the same structural level. The present study thus provided evidence that the speed of sen- tence processing can be predicted from the cognitive load involved in word order alternation in a configurational phrase structure. Keywords: Sentence Processing, Psycholinguistics, Word Order, Scrambling, Sinhalese Language Introduction The Sinhalese language belongs to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages, spoken by approximately 13 million people as their mother tongue in the country of Sri Lanka (Englebretson & Genetti, 2005). Sidat-sangarava, liter- ally meaning “the journal of Sidat”, the well-known grammar book published in the 13th century described the grammatical system of the Sinhalese language. In print, the Sinhalese lan- guage is presented in the Sinhala script which traces its ancestry back more than 2000 years. Sinhalese is used as an instructional language at all schools and the majority of universities. English is an official language as defined by the constitution in Sri Lanka. Sinhalese is composed of two distinct forms, written and spoken. The written and spoken forms differ noticeably in their core grammatical structures (Chandralal, 2010; Englebretson & Genetti, 2005; Miyagishi, 2005; Noguchi, 1984). For example, in the spoken form, the subject of a subordinate clause is marked as nominative, whereas in the written form the subject is marked as accusative (Miyagishi, 2005). The written form is mostly used for reading news on TV or radio, and for making public speeches (Miyagishi, 2005), as well as for printed mate- rials. Generally, the spoken form is very flexible in various syntactic aspects whereas the written form involves many strict grammatical rules. Linguistic studies (e.g., Gair, 1998; Miyagishi, 2003; Ya- mamoto, 2003) suggest that the unmarked or “canonical” order of Sinhalese sentences in written and spoken forms follows the word order of subject-object-verb (SOV). In fact, Kanduboda and Tamaoka (2009, 2010) found SOV as a canonical order by showing that SOV-ordered sentences were processed more quickly and accurately in a sentence correctness decision task than OSV-ordered sentences. Yet, the Sinhalese language al- lows all six possible word orders for active sentences with tran- sitive verbs of SOV, OSV, SVO, OVS, VSO, and VOS (e.g., Gair, 1998; Miyagishi, 2003). This greatly flexible word order alternation indicates a “flat” phrase structure that lacks VP or other phrasal projections within sentences, which supports for the non-configurationality hypothesis (e.g., Farmer, 1984; Hale, 1980, 1982, 1983). Thus, all five altered word orders should be compared together with the presently proposed-canonical order of SOV (Kanduboda & Tamaoka, 2009, 2010) in order to as- certain what the true canonical order is in the Sinhalese lan- guage. The present study, therefore, investigated the effects of word order alternation in the processing of written (Experiment 1) and spoken (Experiment 2) Sinhalese sentences. Possible Word Orders of Sinhalese Sentences The Sinhalese language has a group of function words called nipātha that function somewhat like case markers. The subject (S) in written and spoken Sinhalese is unmarked. Furthermore, when S is animate and the object (O) is inanimate, both S and O are unmarked because animacy provides enough information to determine S and O. In the written and spoken forms, when S and O are both animate, O is usually marked by a nipātha (par- ticles) dative marker -ta. Since a nipātha does not include an accusative marker, -ta may be used for the object of SOV sen- tences in place of an accusative particle. Miyagishi (1998) ex- plained that -ta (or “Tə”) expresses various syntactic relations typical of a dative case-marker. In addition, when S and O are  K. TAMAOKA ET AL. 25 both inanimate, an object noun includes a suffix marking in- animate (-ee/-ii) in the written form, but in the spoken form, no such marking on the object noun. In such a case, word order determines S and O (the first noun is understood as S, and a subsequent noun as O). In the spoken form, the SOV canonical order of an active sentence with a transitive verb in (1) can alter its word order in the five different ways indicated from (2) to (6): 1) SOV amara nimala-ta gehuwa. Amara(φ)NOM Nimala-DAT hit-PAST Amara hit Nimala. (All orders carry the same meaning.) 2) OSV nimala-ta amara gehuwa. Nimala-DAT Amara(φ)NOM hit-PAST 3) SVO amara gehuwa nimala-ta. Amara(φ)NOM hit-PAST Nimala-DAT 4) OVS nimala-ta gehuwa amara. Nimala-DAT hit-PAST Amara(φ)NOM 5) VSO gehuwa amara nimala-ta. hit-PAST Amara(φ)NOM Nimala-DAT 6) VOS gehuwa nimala-ta amara. hit-PAST Nimala-DAT Amara(φ)NOM Describing these word orders based on verb positions, the verb final position of SOV word order, assumed to be the ca- nonical order as shown in (1) is scrambled to create the OSV word order in (2). According to Yamamoto (2003), the verb second position of a SVO Sinhalese sentence in (3) is a secon- dary candidate of canonical word order. Alternation of OVS based on SVO is also an acceptable sentence for carrying the meaning of “Amara hit Nimala”. Furthermore, the verb initial position of VSO in (5) and its altered order of VOS in (6) are also acceptable as correct sentences. Likewise, the assumed-canonical word order of an active sentence with a transitive verb in the written form in (7), meaning “Amara hit Nimala”, can be altered into five different word orders as described from (8) to (12), below: 7) SOV amara nimala-ta gehuwēya. Amara(φ)NOM Nimala-DAT hit-PAST 8) OSV nimala-ta amara gehuwēya. Nimala-DAT Amara(φ)NOM hit-PAST 9) SVO amara gehuwēya nimala-ta. Amara(φ)NOM hit-PAST Nimala-DAT 10) OVS nimala-ta gehuwēya amara. Nimala-DAT hit-PAST Amara(φ)NOM 11) VSO gehuwēya amara nimala-ta. h it-PAST Amara(φ)NOM Nimala-DAT 12) VOS gehuwēya nimala-ta amara. hit-PAST Nimala-DAT Amara(φ)NOM The subject-verb agreement is rigid in the written form, whereas, in the spoken form, it is less concerned. In this SOV sentence, the only difference between the spoken and written form is the ending of the verb: the spoken form -wa (gehuwa) is changed into -wēya (gehuwēya) in the written form. Funda- mentally, these six word order alternations are applicable to both the spoken and written forms. In the present study, all these phrasal alternations are tested by the reaction time para- digm using a sentence-correctness task. Methodology and its issues are discussed the following section. Methodological Issues Reaction (or processing) time is the duration between the presentation of a stimulus and the subsequent behavioral re- sponse, typically a button press. Reaction time is crucial in the reaction time paradigm which has been used for over 40 years in experimental psychology. Since native speakers are expected to perform a language task with a high accuracy in psycholin- guistic studies of lexical and sentence processing, an experi- menter forces them to execute a required task as quickly and as accurately as possible. The present study measured efficiency of sentence processing by examining accuracy and speed. In the case of native speakers of the Sinhalese language, an easy task like sentence-correctness decision for simple sentences is per- formed with relatively higher accuracy. Thus, the critical mea- sure is reaction time, rather than accuracy. Due to syntactic manipulations, sentences with a scrambled order are expected to require longer processing times than the same sentences with a canonical order. The sentence-correctness task measures overall reading time of a whole sentence. Miyamoto and Nakamura (2005) criticized this approach for not being sensitive enough to investigate the details of phrasal processing. They suggested using the self- paced reading method to measure phrasal processing. In the self-paced reading method, participants are required to read one part, often a single phrase of a sentence at a time and press a button to see the next part. The duration time between button presses is interpreted as the reading time for each part. How- ever, this method has seldom detected scrambling effects in simple sentences (e.g., Nakayama, 1995; Tamaoka, Sakai, Kawahara, & Miyaoka, 2003; Yamashita, 1997). This tendency becomes extreme in a simple active sentence with a transitive verb (for details, see Tamaoka & Koizumi 2006). In addition, self-paced reading locks participants’ reading at a certain region, so participants are not allowed to read backward to check al- ready-read phrases. A spill-over tendency is also occasionally observed in which the phrase that follows the target phrase shows a significantly longer reading time. Since the target stimulus Sinhalese sentences in the present experiments con- sisted of three phrases, participants could finish reading a sen- tence by pressing the space bar three times using a three-beat rhythm. With this repetitious behavior, reaction times varied little between phrases. A recent eye-tracking study utilized the sentence-correctness decision task (Tamaoka, Asano, Miyaoka, & Yokosawa, 2009) to investigate the processing of simple canonical and single/ double scrambled-order active sentences with ditransitive verbs. The result showed that pre-head reading times before seeing a verb were delayed for the third noun phrase in both single- and double-scrambled sentences, each compared to canonical sen- tences. However, while the post-head reading times and regres- sion frequencies did not differ between canonical and single- scrambled sentences, double-scrambled sentences showed post- head reading times and regression frequencies that were sig- nificantly longer for all three noun phrases than they were in the other two sentential conditions. Thus, single-scrambled sentences that contain a single filler-gap dependency can be mostly resolved through pre-head parsing in the third noun phrase whereas double-scrambled sentences containing two filler-gap dependencies require heavy post-head parsing. Based on this eye-tracking study, it is assumed that the sentence-cor- rectness decision task includes all of these forward and back- ward readings for scrambled-order sentences that cannot be measured by the self-paced reading method. Since the present study used a simple Sinhalese sentence constructed of only three phrases, the sentence-correctness decision task with whole sentence reading can be considered a reasonable method for measuring the scrambling effects of simple sentences.  K. TAMAOKA ET AL. 26 Experiment 1: Sentence Processing of Sinhalese Written Form Using the sentence-correctness decision task, Experiment 1 measured the processing times and error rates of written-form Sinhalese sentences with six phrasal orders to investigate the syntactic structure of active sentences in the Sinhalese lan- guage. Participants and Procedure Thirty-six native Sinhalese speakers (21 females and 15 males) residing in Sri Lanka participated in the experiment. Their average age was 30 years and 2 months, with a standard deviation of 6 years and 6 months. Participants were asked to determine as quickly and accurately as possible whether a visu- ally presented sentence in the Sinhalese script on a computer monitor was correct by pressing either a YES key or a NO key. Reaction times and error rates for sentence correctness deci- sions were automatically recorded by the computer. Materials As previously discussed in the section of possible word or- ders of Sinhalese sentences, all six phrasal orders are possible in simple active sentences constructed by S, O and V in both the written and spoken forms. Sentences in the written form were used in Experiment 1 (all SOV-ordered 36 sentences are listed in Appendix A). Based on verb positions, these orders could be classified into three verb positions, final (++V), mid- dle (+V+) and initial (V++). Furthermore, according to subject and object orders, S and O word order alternation could be created in each of the three verb positions. In short, six word orders were created as SOV, OSV, SVO, OVS, VSO and VOS. A set of 36 semantically and/or grammatically correct SOV baseline sentences was created using six different word orders (36 × 6 = 216 sentences). In addition, 216 semantically and/or grammatically incorrect sentences were randomly mixed with these correct sentences. Stimulus items did not include sen- tences where both S and O are inanimate, since such sentences feature a suffix (-ee/-ii) marking the object noun in the written form. A counterbalanced design was applied, using six different sets of stimuli assigned to six different groups of participants. Reaction time and accuracy data taken only from correct sen- tences (YES responses) were used for analysis. Analysis an d Resul ts Prior to the analysis of reaction times, extremes among sen- tence decision times (responses shorter than 500 ms or longer than 5000 ms) were coded as missing values. Responses out- side of 2.5 standard deviations at both high and low ranges were replaced by boundaries indicated by 2.5 standard devia- tions from the individual means of participants in each category. The means of correct “yes” and “no” reaction times and error rates for sentence correctness decisions are presented in Table 1. The statistical tests were conducted both for participant (F1) and item (F2) variability. Only correct responses of correct sentences (YES responses) were used for the analysis of reac- tion times. A two-way, 3 × 2 (three verb positions of initial, middle and final × word order alternation of subject and object) ANOVA repeated measures on reaction times showed significant main effects of verb position [F1(2, 70) = 4.837, p < .05; F2(2, 142 ) = 3.753, p < .05] and word order alternation [F1(2, 70) = 8.443, p Table 1. Processing of written-form active Sinhalese sentences with transitive verbs. Reaction time (ms) Error rate (%) Verb positionWord order M SD M SD SOV 1610 313 8.33 8.45 Final position OSV 1739 343 12.9611.35 SVO 1754 321 8.33 10.73 Second position OVS 1757 313 9.26 11.40 VSO 1702 287 9.26 11.05 Initial position VOS 1759 304 8.33 9.96 Simple contrasts for reaction times: SOV < SVO = OVS < OSV = VSO = VOS Note: n = 36. M refers to means. SD refers to standard deviation. < .001; F2(2, 142) = 8.787, p < .001]. The interaction of these variables was also significant [F1(2, 70) = 8.443, p < .001; F2(2, 142) = 8.787, p < .001]. Simple contrasts were conducted on each pair of the six conditions, revealing an ascending order of reaction times as SOV (M = 1610 ms) < VSO (M = 1702 ms) = SOV (M = 1739 ms) = SVO (M = 1754 ms) = OVS (1757 ms) = VOS (M = 1759 ms). The same two-way ANOVA on error rates showed no sig- nificant main effect of either verb position [F1(2, 70) = 1.887, p = .159, n.s.; F2(2, 142) = 0.916, p = .402, n.s.] or word order alternation [F1(1, 35) = 2.016, p = .164, n.s.; F2(1, 71) = 1.503, p = .224, n.s. ]. The interaction between verb position and word order was also not significant [F1(2, 70) = 2.467, p = .092, n.s.; F2(2, 142) = 1.835, p = .163, n.s.]. Discussion In Sinhalese written form, both the verb position and the S and O word order alternation affected the speed of sentence proc- essing. However, simple contrasts in Experiment 1 showed that only sentences with SOV differed from the other five word orders of OSV, SVO, OVS, VSO and VOS. Thus, as linguistic studies (e.g., Gair, 1998; Miyagishi, 2003; Yamamoto, 2003) and psycholinguistic studies (Kanduboda & Tamaoka, 2009, 2010 for Sinhalese; Tamaoka et al., 2005 for Japanese) have suggested, SOV must be the canonical word order of the writ- ten form. Although other alternations are acceptable as correct sentences as seen in generally high error rates, SOV has strong preference as the unmarked “canonical” order. The possible secondary canonical order of SVO proposed by Yamamoto (2003) did not show faster processing in comparison to OSV, OVS, VSO and VOS. Thus, SVO cannot be a candidate for possible secondary canonical order in the written form. How- ever, unlike the written form, the spoken form has a great flexi- bility in syntactic rules, so that it is assumed that word order alternation would strongly affect the processing of Sinhalese sentences in the spoken form. This assumption was the motiva- tion for conducting Experiment 2. Experiment 2: Sentence Processing of Sinhalese Spoken Form As with Experiment 1, Experiment 2 measured the process-  K. TAMAOKA ET AL. 27 ing times and error rates of spoken-form Sinhalese sentences with six phrasal orders to investigate the syntactic structure of active sentences in the Sinhalese language. Participants and Procedure Forty-two native Sinhalese speakers (13 females and 29 males) residing in Japan participated in the experiment. Their average age was 30 years and 2 months, with a standard devia- tion of 6 years and 6 months. The procedure of Experiment 2 was the same as Experiment 1. Materials The number of correct and incorrect stimulus items, coun- terbalanced design for these items and data recording were the same as Experiment 1 (a sample of SOV stimuli is illustrated in Appendix B). When the subject (S) and the object (O) in SOV sentences are both inanimate, both are unmarked in the spoken form. In such a case, word order determines S and O in that a proceeding noun is defined as S, and a subsequent noun as O. Naturally, word order alternations cannot be made for these sentences. Thus, sentences with both S and O inanimate were not included in the stimulus items. Analysis an d Resul ts The data editing process was the same as Experiment 1. The means of correct “yes” and “no” reaction times and error rates for sentence correctness decisions are reported in Table 2. Only correct responses were used for the analysis of reaction times. A 3 × 2 (three verb positions of initial, middle and final × word order alternation of subject and object) ANOVA with repeated measures on reaction times showed significant main effects of verb position [F1(2, 82) = 7.882, p < .001; F2(2, 142) = 7.885, p < .001] and word order alternation [F1(1, 41) = 14.170, p < .001; F2(1, 71) = 12.019, p < .001]. The interaction of these variables was also significant [F1(2, 82) = 8.277, p < .001; F2(2, 142) = 7.515, p < .001]. Simple contrasts were conducted on each pair of the six conditions, revealing an as- cending order of reaction times as SOV (M = 1663 ms) < SVO (M = 1717 ms) = OVS (M = 1735 ms) < VOS (1815 ms) = VSO (M = 1822 ms) = OSV (M = 1824 ms). The same two-way ANOVA on error rates showed no sig- nificant main effect of verb position [F1(2, 82) = 1.139, p = Table 2. Processing of spoken-form active Sinhalese sentences with transitive verbs. Reaction time (ms) Error rate (%) Verb position Word order M SD M SD SOV 1663 349 5.16 6.87 Final position OSV 1824 355 13.2912.22 SVO 1717 341 9.33 11.07 Second position OVS 1735 331 8.33 11.20 VSO 1822 359 8.33 10.89 Initial position VOS 1815 373 13.2915.84 Simple contrasts for reaction times: SOV < SVO = OVS < OSV = VSO = VOS Note: n = 36. M refers to means. SD refers to standard deviation. .325, n.s.; F2(2, 142) = 1.402, p = .249, n.s.], but the effect of word order alternation showed significant [F1(1, 41) = 10.079, p < .01; F2(1, 71) = 17.201, p < .001]. The interaction between verb position and word order was also significant [F1(2, 82) = 6.681, p < .01; F2(2, 142) = 6.345, p < .01]. Simple contrasts were also conducted with each pair of the six conditions, showing an ascending order of error rates as SOV (M = 5.16%) < OVS (M = 8.33%) = VSO (M = 8.33%) = SVO (M = 9.33%) < OSV (M = 13.29%) = VOS (13.29%). Discussion As with the written form, both verb position and word order alternation affected the speed of sentence processing in the spoken form. Simple contrasts conducted on each pair of the six conditions in Experiment 2 showed the intrinsic result of an ascending order, SOV < SVO = OVS < VOS = VSO = OSV. The results of Experiment 2 are intensively discussed in the following section. General Discussion The present study conducted the experiments on the process- ing of Sinhalese active transitive sentences with all six possible word orders of SOV, OSV, SVO, OVS, VSO, and VOS in both written and spoken forms. Analyses on reaction times for sen- tence correctness decisions showed SOV < SVO = OVS = OSV = VSO = VOS for the written form, and SOV < SVO = OVS < OSV = VSO = VOS for the spoken form. Error rates revealed no differences among the six word orders in the sentence proc- essing in the written form while the pattern of SOV < SVO = OVS = VSO < OSV = VOS was shown in the spoken form. The following sections provide discussion in depth. Findings of the Present Study Since reaction times, which reflect cognitive load for actual sentence processing, are fundamentally more sensitive indexes than error rates, the present study focused on the difference in reaction times for the processing of correct active sentences with transitive verbs (i.e., correct YES responses). The finding could be summarized into three points. First, the processing of sentences with SOV word order in both written and spoken forms was the quickest among the six different word orders to be processed for the sentence correct- ness decision task. Thus, as previous studies of the Sinhalese language (e.g., Gair, 1998; Kanduboda & Tamaoka, 2009, 2010; Miyagishi, 2003; Yamamoto, 2003) indicated, SOV must be the canonical word order of the spoken form. Contrary to the non-configurationality hypothesis (Farmer, 1984; Hale, 1980, 1982, 1983), the results for both the written and spoken forms supported the view that the Sinhalese language has a configura- tional phrase structure. Second, sentences with both SVO and OVS word order were processed faster than OSV and the verb-initial position of VSO and VOS in the spoken from. The present study supported the typological study by Yamamoto (2003) indicating the Sinhalese language as exhibiting SOV canonical word order with a poten- tial of SVO in the spoken form. The word order alternation to SVO, with O moving to the right of V at the same level, may have been influenced by the word order of English, which is frequently-used in Sri Lanka as a spoken language for commu- nication. This bilingual situation in Sri Lanka may have re- sulted in the English canonical word order of SVO (and possi-  K. TAMAOKA ET AL. 28 bly OVS) becoming reasonably acceptable in the spoken form of the Sinhalese language. This view, however, should be fur- ther investigated by controlling for the degree of Sinhalese- English bilingualism among participants processing Sinhalese SVO and OVS sentences in comparison to other word orders. Third, the processing of spoken-form sentences showed a clearer trend in speed and accuracy than the written form. This difference must be caused by differences in core grammatical structures between the written and spoken forms, especially with regard to verbs (Chandralal, 2010; Englebretson & Genetti, 2005; Miyagishi, 2005; Noguchi, 1984). Verbs inflect based on the subject’s singular/plural and feminine/masculine features in the written form; consequently, verb forms provide the subject information. In contrast, no such inflection is provided by verb forms in the spoken form. For example, “Amara drank tea” can be expressed as Amara tee biwweeya [Amara(φ)NOM tea- ACC(φ) drink-PAST] in the written from. The verb biwweeya indicates that a subject is third person singular and masculine with past tense. The same meaning of sentence is expected as Amara tee biwwa [Amara(φ)NOM tea-ACC(φ) drink-PAST] in the spoken form. However, the verb in the spoken form indi- cates neither singular/plural nor feminine/masculine informa- tion about the subject. Verbs in the written form can therefore provide basic infor- mation about syntactic structure, especially information about the subject noun phrase (NP-NOM). Therefore, a sentence structure in the written form can be easily constructed using both NP features and information from the verb, which would result in the similar reaction times for sentence processing of the verb-initial positions of VSO and VOS, and the verb-second position of SVO and OVS. In the OSV word order, which is considered as scrambled from the SOV canonical, the verb cannot provide information related to the subject noun phrase until the end of sentence. Thus, OS ended up with similar proc- essing speed of the other four scrambled orders. In contrast, since verbs in the spoken form do not provide any information about the subject, native Sinhalese speakers have to construct syntactic structure using information taken from noun phrases. The next section proposes a possible syntactic parsing mecha- nism in the spoken form taken by native Sinhalese speakers. Processing Model for Sinhalese Sentences in the Spoken Form The important question remains: how we can explain the complex results regarding the speed of sentence processing in the flexible spoken form of the Sinhalese language. In this sec- tion, we present a tentative account for processing speed based on the idea of Structural Distance Hypothesis proposed by Hawkins (1999) or O’Grady (1997). Processing asymmetry is observed between subject relative clauses (SRC) and object relative clauses (ORC). The Structural Distance Hypothesis accounts for this asymmetry by assuming that the number of nodes between the filler and the gap determine the processing load of relative clauses. For instance, in the SRC example “the reporter that attacked the senator,” the filler NP “the reporter” is separated from the gap by two nodes, but the filler NP is separated from the gap by three nodes in the ORC example “the reporter that the senator attacked”. The Structural Distance Hypothesis thus correctly predicts that SRC is processed faster than the ORC. In the processing model for Sinhalese sentences, the present study assumed that subject and object could appear on either side of a verb phrase (VP) or a verb as represented in Figure 1. The three different degrees of reaction times corre- spond exactly to the three different types of word order alterna- tion expected from a configurational phrase structure. First, the fastest reaction time for SOV word order corresponds to the canonical order of SOV without any structural change, repre- sented as [TP S [VP O V] ]. In this structure, native Sinhalese speakers do not need to construct a filler-gap dependency. With no processing load to construct dependency, SOV resulted in the shortest reaction times among the six differently-ordered sentences. Second, as shown in Figure 2, word order alternation at the same structural level can be involved in both SVO and OVS, [TP S [VP t1 V O1] ] for SVO and [TP t1 [VP O V ] S1] for OVS, resulting in slower reaction speeds than the canonical order of SOV. In a sentence with SVO structure, O moves to the right of V at the same level. Similarly, in a sentence with OVS structure, S moves to the right of VP at the same level. Since both SVO and OVS require a single word order alternation at the same phrasal level, there is just one intervening node between the filler and the gap. The processing speeds of these sentences were slower than the canonical SOV, but faster than OSV, VSO and VOS. Third, as illustrated in Figure 3, word order alternation takes place at a different structural level, for OSV [TP’ O1 [TP S [VP t1 V ] ] ] and for VSO [TP’ V1 [TP S [VP O t1] ] ]. Two word order alternations take place within the same level for VOS [TP t1 [VP t2 V O2] S1]. All these word order alternations for OSV, VSO and VOS require an extra cognitive load for sentence process- ing, even heavier than for the single word order alternation at the same structural level for SVO and OVS. Summary Based on reaction times for sentence correctness decisions, the present study indicated SOV < SVO = OVS = OSV = VSO = VOS for the written form, and SOV < SVO = OVS < OSV = VSO = VOS for the spoken form. The fastest reaction time for TP SVP OV ・・・ ・・・ SOV structure Figure 1. Canonical word order. TP TP SVP t1VP S1 t1VO 1OV SVO structure ・・・ ・・・ OVS structure Figure 2. A word order alternation for SVO and OVS at the same level.  K. TAMAOKA ET AL. 29 Figure 3. A word order alternation for SVO and OVS at the same level. SOV word order corresponds to the canonical order SOV [TP S [VP O V] ] for both the written and spoken forms. The lack of agreement features on verbs in the spoken form may allow a great flexibility in word order, which creates different speeds in the six possible word orders. The present study proposed a processing model for Sinhalese sentences in the spoken form as follows. Word order alternation at the same structural level is involved in both SVO and OVS, [TP S [VP t1 V O1] ] for SVO and [TP t1 [VP O V ] S1 ] for OVS, resulting in a slower reaction speed than the canonical order of SOV. Word order alternation takes place at a different structural level, for OSV and VOS [TP’ O1 [TP S [VP t1 V ] ] ] for OSV, [TP’ V1 [TP S [VP O t1] ] ] for VSO, and double word order alternations take place within the same level as [TP t1 [VP t2 V O2] S1] for VOS. These word order alter- nations for OSV, VSO and VOS require an extra cognitive load for sentence processing, even heavier than for a single word order alternation of SVO and OVS taking place at the same structural level. As depicted in the present study, the speed of sentence processing can be predicted from the cognitive load involved in word order alternation in a configurational phrasal structure. Acknowledgements We are grateful to anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions. This study reported here was par- tially supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 23320106 and no. 22222001) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. References Chandralal, D. (2010). Sinhala. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Englebretson, R., & Genetti, C. (Eds.) (2005). Santa Barbara papers in linguistics: Proceeding from the workshop on Sinhala linguistics. Department of Linguistics at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Farmer, A. K. (1984). Modularity in syntax: A study of Japanese and English. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Gair, W. J. (1998). Syntax: Configuration, order, and grammatical function. In L. C. Barbara (Ed.), Studies in South Asian Linguistics; Sinhala and Other South Asian Languages (pp. 47-110). New York: Oxford University Press. Hale, K. (1980). Remarks on Japanese phrase structure: Comments on the papers on Japanese syntax. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, 2, 185-203. Hale, K. (1982). Preliminary remarks on configurationality. North East Linguistic Society, 12, 86-96. Hale, K. (1983). Warlpiri and the grammar of non-configurational language. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 1, 5-47. doi:10.1007/BF00210374 Hawkins, J. A. (1999). Processing complexity and filler-gap dependen- cies across grammars. Language, 75, 244-285. doi:10.2307/417261 Kanduboda, A. B. P., & Tamaoka, K. (2009). Priority information in determining canonical word order of colloquial Sinhalese sentences. Proceedings of the 139th Conference of the Linguistic Society of Ja- pan, 1, 32-37. Kanduboda, A. B. P., & Tamaoka, K. (2010). Priority information for canonical word order of written Sinhala sentences. Proceedings of the 140th Conference of the Linguistic Society of Japan, 358-363. Miyagishi, T. (1998). Shinharago Tə kaku meishi no imiteki tokuchoo (Semantic characteristic of nouns marked with the suffix “Tə” in Sinhala). Yasuda Joshi Daigaku Kiyoo (Yasuda Women’s University Bulletin), 27, 57-74. Miyagishi, T. (2003). Shinharago no dakkaku/gukaku meishi to dooshi no musubitsuki (Relationship between ablative/instrumental case nouns). Yasuda Joshi Daigaku Kiyoo (Yasuda Women’s University Bulletin), 31, 1-26. Miyagishi, T. (2005). Shinharago ni okeru jyuuzokusetsu no taikaku shugo (Accusative subject of subordinate clause in Sinhalese). Ya- suda Joshi Daigaku Kiyoo (Yasuda Women’s University Bulletin), 33, 15-26. Miyamoto, E. T., & Nakamura, M. (2005). Unscrambling some mis- conceptions: A comment on Koizumi and Tamaoka (2004). Gengo kenkyu (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan), 128, 113-129. Nakayama, M. (1995). Scrambling and probe recognition. In R. Ma- zuka and N. Nagai (Eds.), Japanese Sentence Processing (pp. 257-273). Hillsdale, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum. Noguchi, T. (1984). Shinhara-go nyuumon (Introductory to the Sin- halese language). Tokyo: Daigaku Shorin. O’Grady, W. D. (1997). Syntactic development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Tamaoka, K., & Koizumi, M. (2006). Issues on the scrambling effects in the processing of Japanese sentences: Reply to Miyamoto and Nakamura (2005). regarding the experimental study by Koizumi & Tamaoka (2004). Gengo Kenkyu (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan), 129, 181-226. Tamaoka, K., Sakai, H., Kawahara, J., & Miyaoka, Y. (2003). The effects of phrase-length order and scrambling in the processing of visually-presented Japanese sentences. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 32, 431-454. doi:10.1023/A:1024851729985 Tamaoka, K., Sakai, H., Kawahara, J., Miyaoka, Y., Lim, H., & Koi- zumi, M. (2005). Priority information used for the processing of Japanese sentences: Thematic roles, case particles or grammatical functions. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 34, 273-324. doi:10.1007/s10936-005-3641-6  K. TAMAOKA ET AL. 30 Tamaoka, K., Asano, M., Miyaoka, Y., & Yokosawa, K. (2009). Pre- and post-head phrasal parsing of canonical and scrambled Japanese active sentences measured by the eye-tracking method. Proceedings of the 138th meeting of the Linguistic Society of Japan, 270-275. Yamamoto, H. (2003). Sekai shogengo no chiriteki keitooteki gojyun bunrui to sono hensen (An area distribution of word order among world languages and their changes). Hiroshima: Keisuisha. Yamashita, H. (1997). The effects of word-order and case marking information on the processing of Japanese. Journal of Psycholinguis- tic Research, 26, 163-188. doi:10.1023/A:1025009615473  K. TAMAOKA ET AL. 31 Appendix A. A List of Written-Form Active Sentences in Experiment 1 The 36 canonical order subject-object-verb (SOV) written- from sentences for correct YES responses are listed below. Based on these 36 sentences, five more phrasal orders were created as OSV, SVO, OVS, VSO and VOS (36 × 6 = 216 sentences in total). 1 nayā godura gillēya snake (NOM, anim) bait (ACC, inam) swallow (V + PAST) (A) snake swallowed bait. 2 Gangā epal kēwāya Ganga (NOM, anim) apple (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) Gangā ate (an) apple. 3 hāwā undupiyaliya kēwēya rabbit (NOM, anim) grass (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) rabbit ate grass. 4 māmā mālu gatthā uncle (NOM, anim) fish (ACC, inam) take (V + PAST) (My) uncle bought fish. 5 sunil gas kepuwēya Sunil (NOM, anim) tree (ACC, inam) cut (V + PAST) Sunil cut (a) tree. 6 weddā kēma heduwēya hunter (NOM, anim) food (ACC, inam) cook (V + PAST) (A) hunter cooked food. 7 kumariya giitha geyuwāya princess (NOM, anim) songs (ACC, inam) sing (V + PAST) (A) princess sang song. 8 nanngi salli dunnāya sister (NOM, anim) money (ACC, inam) give (V + PAST) (A) sister gave (some) money. 9 waduwā putuwa heduwēya carpenter (NOM, anim) chair (ACC, inam) repair (V + PAST) (A) carpenter repaired (a) chair. 10 girawā ammba kēwēya parrot (NOM, anim) mango (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) parrot ate (a) mango. 11 amara bath kēwēya Amara (NOM, anim) rice (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) Amara ate rice. 12 nanngi sindu liwwāya sister (NOM, anim) songs (ACC, inam) write (V + PAST) (My) sister wrote (a) song. 13 ballā elawalu kēwēya dog (NOM, anim) vegetables (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) dog ate vegetables. 14 akkā midula athugēwāya sister (NOM, anim) garden (ACC, inam) sweep (V + PAST) (A) sister swept (the) garden. 15 gawayā thanakola kēwēya cow (NOM, anim) grass (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) cow ate grass. 16 ammā bath heduwēya mother (NOM, anim) rice (ACC, inam) cook (V + PAST) (My) mother cooked rice. 17 kamala gedaraweda iwarakalāya Kamala (NOM, anim) homework (ACC, inam) finish (V + PAST) Kamala finished (this) homework. 18 api mal keduwemu we (NOM, anim) flowers (ACC, inam) pluck (V + PAST) We plucked flowers. 19 nanngi pahana niwwāya sister (NOM, anim) lamp (ACC, inam) blow out (V + PAST) (My) sister blew out (the) lamp. 20 siiyaa rewla kepuwēya grandfather (NOM, anim) beard (ACC, inam) cut (V + PAST) (My) grandfather cut (his) beard. 21 hāwā kerat kēwēya sister (NOM, anim) lamp (ACC, inam) blow out (V + PAST) (My) sister blew out (the) lamp. 22 achchii pedura heduwāya grandmother (NOM, anim) mat (ACC, inam) make (V + PAST) (My) grandmother made (the) mat. 23 chaamara chithra endēya Chaamara (NOM, anim) drawing (ACC, inam) paint (V + PAST) Chaamara painted (the) drawing(s). 24 sinhayā mas kēwēya lion (NOM, anim) meat (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) lion ate (the) meat. 25 thaththā baisikalaya heduwēya father (NOM, anim) bicycle (ACC, inam) make (V + PAST) (My) father made (the) bicycle. 26 mallii kumbura ketuwēya brother (NOM, anim) paddy (ACC, inam) crop (V + PAST) My brother cropped (the) paddy. 27 nettuwā netum netuwēya dancer (NOM, anim) dance (ACC, inam) dance (V + PAST) (A) dancer danced (a dance). 28 waduwā ge heduwēya carpenter (NOM, anim) chair (ACC, inam) break (V + PAST) (A) carpenter broke (the) chair. 29 gayāni polsambōla heduwāya Gayani (NOM, anim) coconut salad (ACC, inam) make (V + PAST) Gayani made coconut salad. 30 monarā palathuru kēwēya peacock (NOM, anim) fruits (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) peacock ate fruits. 31 ajith kuudu heduwēya Ajith (NOM, anim) lantern (ACC, inam) make (V + PAST) Ajith made lantern(s). 32 kamal bera gehuwēya Kamal (NOM, anim) drum (ACC, inam) hit (V + PAST) Kamal played drums. 33 niila sarama mehuwāya Niila (NOM, anim) sarama (ACC, inam) stitch (V + PAST) Niila stitched sarama (cloth). 34 amila kathā kiwwēya Amila (NOM, anim) story (ACC, inam) tell (V + PAST) Amila told storie(s). 35 dayā sarungal yewwēya Daya (NOM, anim) kite (ACC, inam) fly (V + PAST) Daya flied (a) kite. 36 piyadāsa pol genāwēya Piyadasa (NOM, anim) coconut (ACC, inam) bring (V + PAST) Piyadasa brought coconut(s). Appendix B. A List of Spoken-Form Active Sentences in Experiment 2 The canonical order of subject-object-verb (SOV) 36 spo-  K. TAMAOKA ET AL. 32 ken-form sentences for correct YES responses were listed be- low. Based on these 36 sentences, five more phrasal orders were created as OSV, SVO, OVS, VSO and VOS (36 × 6 = 216 sentences in total). 1 nayā godura gillā snake (NOM, anim) bait (ACC, inam) swallow (V + PAST) (A) snake swallowed bait. 2 gangā epal kēwā Ganga (NOM, anim) apple (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) Gangā ate (an) apple. 3 hāwā undupiyaliya kēwā rabbit (NOM, anim) grass (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) rabbit ate grass. 4 māmā mālu gatthā uncle (NOM, anim) fish (ACC, inam) take (V + PAST) (My) uncle bought fish. 5 sunil gas kepuwā Sunil (NOM, anim) tree (ACC, inam) cut (V + PAST) Sunil cut (a) tree. 6 weddā kēma heduwā hunter (NOM, anim) food (ACC, inam) cook (V + PAST) (A) hunter cooked food. 7 kumariya giitha geyuwā princess (NOM, anim) songs (ACC, inam) sing (V + PAST) (A) princess sang song. 8 nanngi salli dunnā sister (NOM, anim) money (ACC, inam) give (V + PAST) (A) sister gave (some) money. 9 waduwā putuwa heduwā carpenter (NOM, anim) chair (ACC, inam) repair (V + PAST) (A) carpenter repaired (a) chair. 10 girawā ammba kēwā parrot (NOM, anim) mango (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) parrot ate (a) mango. 11 amara bath kēwā Amara (NOM, anim) rice (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) Amara ate rice. 12 nanngi sindu liwwā sister (NOM, anim) songs (ACC, inam) write (V + PAST) (My) sister wrote (a) song. 13 ballā elawalu kēwā dog (NOM, anim) vegetables (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) dog ate vegetables. 14 akkā midula athugēwā sister (NOM, anim) garden (ACC, inam) sweep (V + PAST) (A) sister swept (the) garden. 15 gawayā thanakola kēwā cow (NOM, anim) grass (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) cow ate grass. 16 ammā bath heduwā mother (NOM, anim) rice (ACC, inam) cook (V + PAST) (My) mother cooked rice. 17 kamala gedaraweda iwarakalā Kamala (NOM, anim) homework (ACC, inam) finish (V + PAST) Kamala finished (this) homework. 18 api mal keduwā we (NOM, anim) flowers (ACC, inam) pluck (V + PAST) We plucked flowers. 19 nanngi pahana niwwā sister (NOM, anim) lamp (ACC, inam) blow out (V + PAST) (My) sister blew out (the) lamp. 20 siiyaa rewla kepuwā grandfather (NOM, anim) beard (ACC, inam) cut (V + PAST) (My) grandfather cut (his) beard. 21 hāwā kerat kēwā sister (NOM, anim) lamp (ACC, inam) blow out (V + PAST) (My) sister blew out (the) lamp. 22 achchii pedura heduwā grandmother (NOM, anim) mat (ACC, inam) make (V + PAST) (My) grandmother made (the) mat. 23 chaamara chithra endā Chaamara (NOM, anim) drawing (ACC, inam) paint (V + PAST) Chaamara painted (the) drawing(s). 24 sinhayā mas kēwā lion (NOM, anim) meat (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) lion ate (the) meat. 25 thaththā baisikalaya heduwā father (NOM, anim) bicycle (ACC, inam) make (V + PAST) (My) father made (the) bicycle. 26 mallii kumbura ketuwā brother (NOM, anim) paddy (ACC, inam) crop (V + PAST) My brother cropped (the) paddy. 27 nettuwā netum netuwā dancer (NOM, anim) dance (ACC, inam) dance (V + PAST) (A) dancer danced (a dance). 28 waduwā ge heduwā carpenter (NOM, anim) chair (ACC, inam) break (V + PAST) (A) carpenter broke (the) chair. 29 gayāni polsambōla heduwā Gayani (NOM, anim) coconut salad (ACC, inam) make (V + PAST) Gayani made coconut salad. 30 monarā palathuru kēwā peacock (NOM, anim) fruits (ACC, inam) eat (V + PAST) (A) peacock ate fruits. 31 ajith kuudu heduwā Ajith (NOM, anim) lantern (ACC, inam) make (V + PAST) Ajith made lantern(s). 32 kamal bera gehuwā Kamal (NOM, anim) drum (ACC, inam) hit (V + PAST) Kamal played drums. 33 niila sarama mehuwā Niila (NOM, anim) sarama (ACC, inam) stitch (V + PAST) Niila stitched sarama (cloth). 34 amila kathā kiwwā Amila (NOM, anim) story (ACC, inam) tell (V + PAST) Amila told storie(s). 35 dayā sarungal yewwā Daya (NOM, anim) kite (ACC, inam) fly (V + PAST) Daya flied (a) kite. 36 piyadāsa pol genāwā Piyadasa (NOM, anim) coconut (ACC, inam) bring (V + PAST) Piyadasa brought coconut(s).

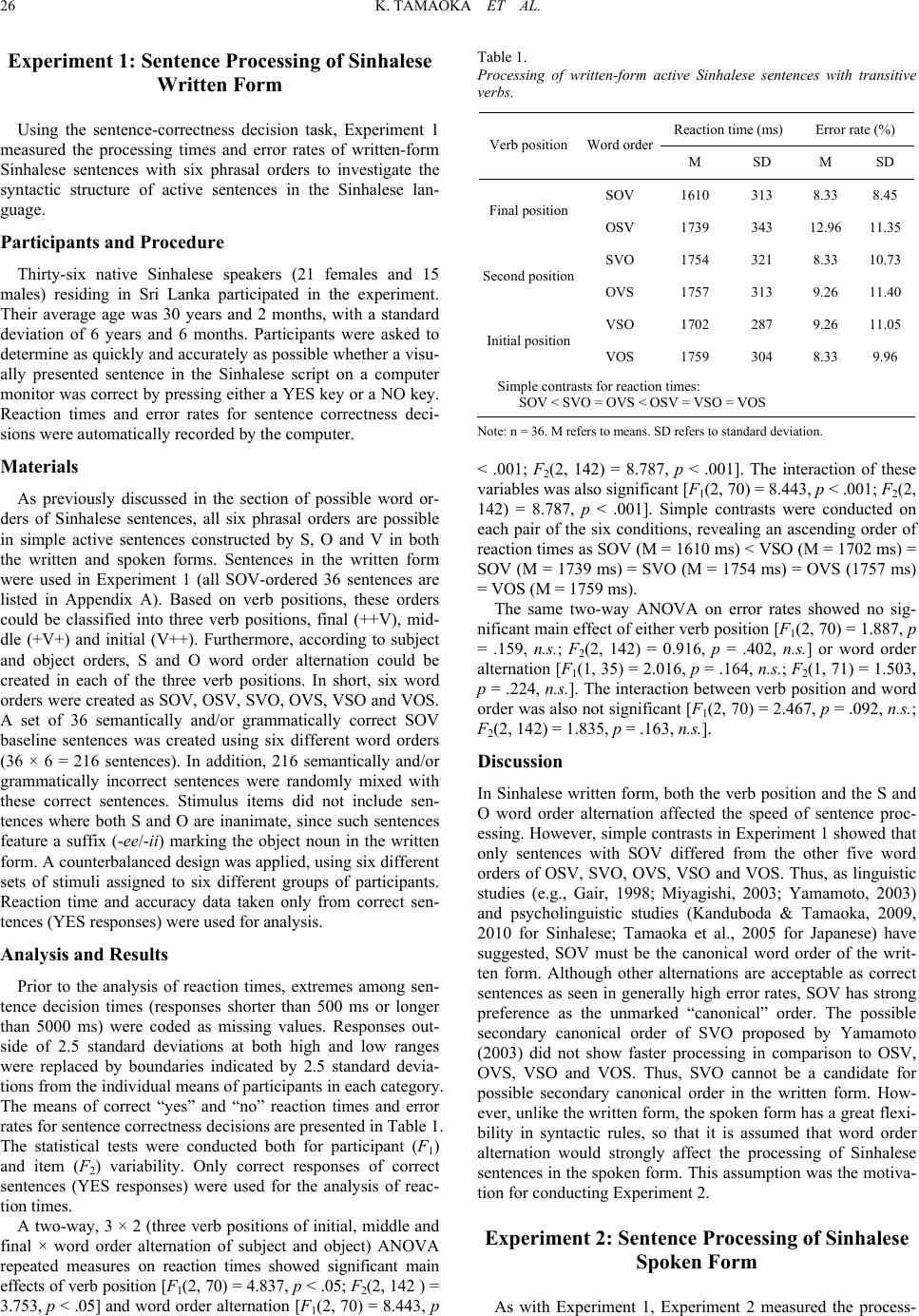

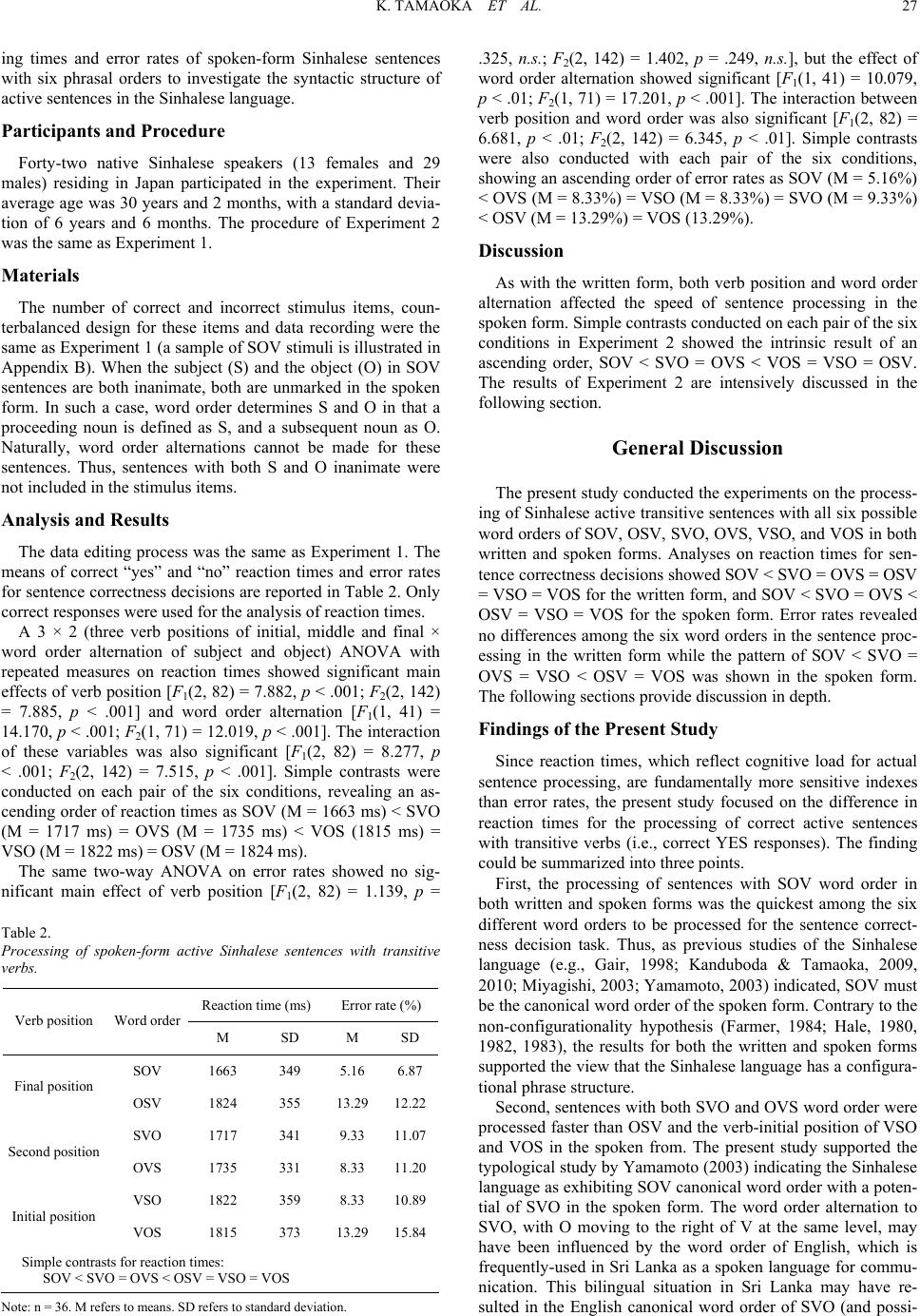

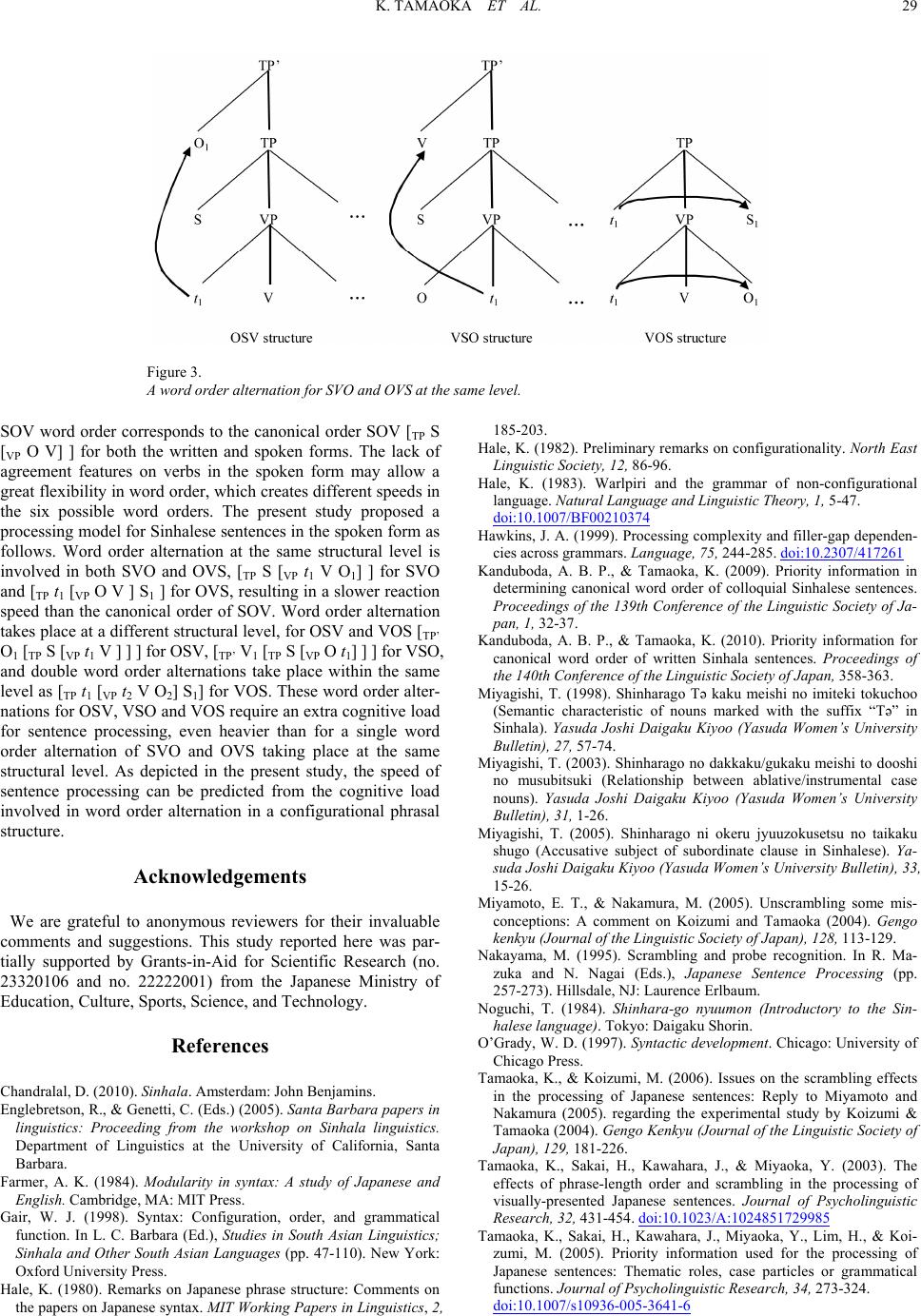

|