Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2011. Vol.1, No.2, 13-23 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/ojml.2011.12003 Prefixes of Degree in English: A Cognitive-Corpus Analysis Zeki Hamawand Department of English, College of Education, University of Kirkuk, Kirkuk, Iraq. Email: Zeki.hamawand@gmail.com Received November 9th, 2011; revised December 9th, 2011; accepted December 26th, 2011. This paper provides a new analysis of prefixes of degree in English which include hyper-, mega-, super-, sur- and ultra-. In carrying out the analysis, it adopts two approaches. Theoretically, it adopts Cognitive Semantics (CS) and tries to substantiate some of its tenets with reference to prefixation. One tenet is that linguistic items are meaningful. On this basis, the paper argues that prefixes of degree have a wide range of meanings that gather around a central sense. Another tenet is that the meaning of a linguistic item is best understood in terms of the domain to which it belongs. On this basis, the paper argues that prefixes of degree form a set in which they high- light not only similarities but also differences. A further tenet is that the use of an expression is governed by the particular construal imposed on its content. On this basis, the paper argues that a derived word results from the particular construal the speaker chooses to describe a situation. Empirically, the paper adopts Corpus Linguistics, which helps identify the distinctive collocates associated with the members of a pair and, consequently, reveal the subtle differences in meaning between them. The aim is to show that the members of a pair are not synony- mous, as has hitherto been claimed by previous paradigms or current dictionaries, bu t dis tincti ve in use. Keywords: Category, Collocate, Construal, Domain, Perspective, Rivalry Introduction In English, one way of forming nouns or adjectives is by prefixation. Nouns, for example, can be derived from roots of different syntactic categories. Nouns can be derived from verbs as in hyper-ventilate from ventilate, from adjectives as in hy- per-active from active, and from nouns as in hyper-inflation from inflation. In some cases, only one word can be derived from a root, as in hyper-link from link. In other cases, two, sometimes more, words can be derived from a root, as in su- per-fast/ultra-fast from fast. This type of derivation is known as morphological rivalry, the alternation between two, or more, prefixes in deriving new forms from the same root, exhibiting both phonological distinctness and semantic similarity. The scope of the present analysis covers the formation of new words by means of prefixes of degree, particularly those of high de- gree which includes hyper-, mega-, super-, sur- and ultra-. In this respect, some questions are posed. The first question is: do prefixes of degree display multiple meanings, and if so, how are the meanings related? The second question is: do prefixes of degree have distinct meanings which contrast sharply with one another, and if so, what provides the basis for the contrast? The third question is: are derivatives formed from the same root, but with different prefixes of degree, semantically distinct from one another, and if so, what triggers the distinction? The task of the paper will be to answer these questions. To answer these questions, I organise the paper in the fol- lowing way. Section 2 provides a brief overview of the stances of the theoretical paradigms on the nature of affixes in general and the question of rivalry in particular. The section is subdi- vided into three parts. The first and the second parts present the main theoreti cal paradigms, namely the generative and the cog- nitive ones. The aim is to show how the issue of rivalry has been addressed by them. The third part serves to assess the descriptive adequacy of each of the theoretical paradigms. Sec- tion 3 constitutes the central part of the paper. It introduces the current analysis, which is rooted in the cognitive paradigm. The section elaborates on three fundamental tenets of Cognitive Semantics. Accordingly, the section is subdivided into three parts. The first part discusses the tenet of category. The second part handles the tenet of domain. The third part tackles the tenet of construal. The aim is to show how such tenets help one to understand the contributions made by prefixes of degree in the formation of words and the roles played by them in resolving the difficulty surrounding the interpretation of the formed words. Section 4 recaps the main points and reports the findings of the study. Theoretical Paradigms The issue of derivational morphology in general and mor- phological rivalry in particular has captured somewhat the at- tention of theoretical paradigms dealing with language structure. Across the range of mainstream linguistic theories, there are essentially two fundamental views on language. The first view is referred to as formalist because it considers language as a system that should be studied in isolation, both from meaning and from cognitive processes. This view is concerned with the formal relationship between linguistic elements independently of the meanings they hold. This view is associated with the theory of Generative Grammar (Chomsky, 1957, 1965), which describes language only with reference to formal rules. The second view is referred to as functionalist because it considers language as a tool of communication, where language structure reflects what people use language for. This view focuses on form-meaning relationships between linguistic elements. This view is associated with the theory of Cognitive Grammar (Langacker, 1987, 1991), which describes the formal aspect of language only with reference to semantics. The Generative Paradigm Linguists involved in the generative paradigm, especially Chomsky (1981: p. 4), believe that affixes do not have semantic content and the meanings of the complex words they form are  Z. HAMAWAND 14 not motivated. There is no straightforward relationship between the form of a linguistic element and the meaning it expresses. Given such a core assumption, the dominant tendency deems a prefix a meaningless linguistic element, which is summoned simply to derive a new word. That is, a prefix turns up in the initial position of the derived word, plays no role in its semantic make-up, and acts as a mere category classifier. Unlike a lex- eme which has an identifiable meaning, a morpheme, as Beard (1981: p. 196) claims, has no meaning apart from signalling that a derivation has taken place. The difference in meaning between derivatives does not belong to the function of the affix but to the lexeme. Spencer (2001: p. 227) clarifies this by say- ing: “Thus, the derivational morphology which creates the ad- jectives changes the syntactic category of the word but does not add any element of meaning and thus, strictly speaking, is a kind of cranberry suffix”. Rival derivatives are lexical excep- tions which should, as Aronoff (1976) proposes, be left to the area of lexicology. Within the context of the generative paradigm, two ap- proaches to morphology have been pursued. The first approach assumes that morphological derivations are related by trans- formational rules. Since transformations do not change meaning, transformationally-related derivations, i.e. those sharing the same deep structure, are semantically equivalent. This approach has been brought to the attention of linguists by Chomsky who considers morphological constructions as the output of phrase structure rules operating on lexical items. Relating this to pre- fixes of degree, the members of a pair are claimed to have the same deep structure, and are hence similar in meaning. The surface differences are the result of different transformational operations. Rival prefixes are treated as alternatives, and the choice between them is the result of different syntactic trans- formations. For Beard (1995), the existence of rival affixes is a matter of idiosyncrasy and an instance of synonymy. The rival affixes are in fact different manifestations of a single affix. The derived words have meaning, but the difference in meaning is not related to the function of the prefixes because he considers them meaningless. This is so because the logic of this approach separates form and meaning in derivational morphology. The second approach assumes that morphological derivations are not related by transformational rules. Transformational rules and deep structures are excluded from derivational morphology. Word-formation cannot be governed by syntactic transforma- tions; rather it is governed by factors of other nature. This ap- proach has been advocated by linguists like Selkirk (1982) and Lieber (2004). For them, affixes are lexical items that have semantic and phonological characteristics. Likewise, affixes have syntactic characteristics which include subcategorisation frames such as [V-]N, meaning attach a suffix to a verb to form a noun. Some scholars, as we will see below, include such fac- tors in their analyses, where a specific consideration mediates the relationship between the base and the affix. Relating this to prefixes of degree, the members of a word pair are claimed to be in one way or another different. Rival prefixes are treated as alternatives, and the choice between them can be explained in terms of three types of co-occurrence restrictions: the morpho- logical transparency of the base, the phonological property of the affix, and the semantic type of the base. Aronoff (1976: pp. 51-52) attributes the choice between rival suffixes to the shape of the base. For example, -ity is said to be more productive with -ic and -ile bases than -ness is, and -ness is more productive with -ive and -ous bases than -ity is, al- though the other suffix is not impossible in either case. As for stress, Aronoff (1976: p. 40) states that -ness follows a word boundary and -ity a morpheme boundary. Plag (1999) imputes the alternation between the rival suffixes -ize, -ify and -ate to the phonology of each suffix. According to syllable pattern, -ise attaches to disyllabic stems as in technicise, whereas -ify at- taches to monosyllabic stems as in technify. According to stress pattern, formations in -ise are stressed on the pre-penultimate syllable as in flúoridise, while formations in -ate are stressed on the penultimate syllable as in flúoridate. Aronoff & Cho (2001: pp. 167-173) ascribes the selection of rival suffixes to the cate- gory of the base. A base which expresses a temporary property selects the suffix -ship. For example, friendship denotes a prop- erty that holds at a given time. In contrast, a base which ex- presses a stable property selects the suffix -hood. For example, sisterhood denotes a property that holds all the time. The Cognitive Paradigm Linguists working in the cognitive paradigm, distinctively Lakoff (1987: p. 228), argue that the primary purpose of lan- guage is to frame thoughts and convey them in communication. Language knowledge and language use appear to interact. The link between form and meaning is not arbitrary but motivated. Langacker (1987: p. 82) contends that syntactic structure is determined by a set of cognitive principles, and there is a direct mapping from a cognitive structure to a syntactic structure. Under this paradigm, a prefix is treated as a reflection of a conceptual structure, and so associated with a variety of mean- ings. The potential context in which a prefix appears is a re- sponse to the communicative needs of the discourse. In Bybee’s (1985: p. 19) analysis, each distinct sense of a word is associ- ated with a distinction in form, and the form of a word is shaped in part by conceptual principles. Morphological rivalry is described in terms of features present on the surface, which includes reference to all kinds of knowledge, be it linguistic or non-linguistic. In the cognitive paradigm, meaning is the most important factor in the choice between rival prefixes. The surface struc- ture of an expression is directly linked to its meaning. There are no rules akin to transformations. A morpheme is conceived as a unit of form and meaning. Just as a plus sign has a meaning (addition) and a form (+) to express it, a morpheme also has a meaning that is expressed by sound waves in speech or by let- ters in writing. According to this paradigm, neither the prefixes are in complementary distribution nor the pairs they derive are in free variation. The difference which determines their distri- bution resides in semantics rather than phonology. Both ul- tra-confident and super-confident are derived from the adjec- tive confident, but they are different in use. In The captain is ultra-confident, the adjective ultra-confident means “The cap- tain is confident to an undue degree”. In The captain is super- confident, the adjective super-confident means ‘The captain is confident to an intense degree’. Within the context of the cognitive paradigm, there have been two approaches to morphology. The first approach argues that the choice between rival affixes is due to the semantics of the affix. In Riddle’s (1985: pp. 435-461) analysis, the suffix -ness tends to denote an embodied attribute, whereas the suffix -ity tends to denote an abstract or concrete entity. In The bru- talness/brutality of Jill’s remarks shocked us, either noun is possible, but the resulting sentences have different meanings. The nominal form ending in -ness focuses on the brutal nature of the remarks themselves, while the nominal form ending in -ity focuses on their utterance as being brutal. This approach, however, is based on invented data as some members of the  Z. HAMAWAND 15 pairs she exemplifies cannot be found in the BNC. The second approach argues that the selection of a rival suffix is the result of the semantics of the derivative. Górska (1994: pp. 413-435, 2001: pp. 189-202) generalises the difference between privative adjectives ending in -less and -free in terms of control and in- tention. In derivatives such as moonless night, the speaker has neither control over the course of events nor the intention to change them. In derivatives such as smoke-free city, the speaker has both control over the course of events and the intention to change them to fulfil a desire. This distinction is at times inef- fective for it does not work in such examples as a stainless watch, a cordless telephon e, etc. Paradigm Assessment The prime objective of the present paper is to show the direct relevance of meaning to the phenomenon of derivational mor- phology. Prefixes, I argue, have meanings of their own, which contribute to the semantic import of the host roots. Two rival prefixes can describe a conceptual content represented by a root, but each does so in its own way. In each case, the prefix serves to highlight a different facet of the root’s content. Each of the resulting derivatives encodes therefore a distinct meaning. In word formation, a prefix is the most important part because it lends its character to the whole derivative. This is so because it adds to the derivative a new shade of meaning. For an extensive coverage of the present analysis of morphological rivalry, see Section 3. The purpose behind discussing the previous ap- proaches has been to find out if they have any beneficial effect on the present analysis or to see if the present argument can build on any of them. A survey of the foregoing discussions, however, reveals a clash between the approaches with reference to the treatment of affixal rivalry. Let us now assess whether the previous hypotheses have any bearing on the present work. For the present analysis, the research done in the generative paradigm is inadequate for three reasons. First, the first ap- proach within the generative paradigm rules out meaning as a possible factor in the choice between rival affixes. This ap- proach assumes that the rival affixes are derived from the same underlying structure, and so the derivatives they form are syn- onymous. Second, the other approach within the generative paradigm instructs speakers to judge rival affixes mainly on the basis of formal rules or structural co-occurrence. This factor seems to work in some cases, but it fails to work in many others. As shown by the last example, it is neither the phonological form of the root nor the etymological source of the prefix that motivates the choice; it is something that belongs, I argue, to the factor of meaning. The adjective confident accepts both ultra- and super- without any regard to phonology or etymol- ogy. No one has considered the choice to be a function of a difference in meaning between the prefixes. Third, generative morphologists in general do not recognise the role of the speaker as a conceptualiser of a situation in making the choice. In theory, the research carried out in the cognitive paradigm is helpful for three reasons. First, cognitive morphologists con- sider meaning the most important factor in the choice between rival prefixes. The prevalent dictum is that a difference in form always spells a difference in meaning. Accordingly, if two al- ternative forms exist, there must be a difference in their mean- ings. Second, cognitive morphologists stress the fact that se- mantically the rival prefixes are dissimilar and the derivatives they form are distinct. The presence of rival prefixes is due to the polysemy of the root that hosts them. On the surface, rival prefixes seem to perform the same function, but a close inves- tigation of their behaviours makes it clear whether or not they have individual meanings. It is, therefore, the semantics and not the form or phonology that determines the distribution of rival prefixes. Third, cognitive morphologists recognise the role of the speaker in making the choice, by matching his or her con- ceptualisation with the right expression hosting the right prefix. In practice, however, the studies conducted so far are inade- quate. One reason is that they provide only a superficial ac- count of the mechanism underpinning affixal rivalry. That is they fail to provide any detailed distinctions between the oc- currences of the rival affixes. This is so because their charac- terisation is based on individual cases, and so the evidence they present is insufficient. Another reason is that little focus has been devoted to the multiplicity of prefixes in general and the topic of rivalry between pairs of prefixes in particular. They don’t exert any effort to specify the paradigmatic sets of mor- phological rivals and to define the (dis)similarity existing among them. Consequently, they neglect to look at the rival prefixes as a coherent class in morphology, a class whose members may represent the same concept but have contrastive behaviour. Of all the works on affixal rivalry, only Riddle’s analysis is compatible with my account of prefixation. In both accounts, the choice is simply motivated by the meaning of the affix. However, the present account differs from Riddle’s analysis in two respects. Firstly, Riddle’s analysis ascribes the distinctions between rival suffixes to semantics, with emphasis laid on their historical origins. By contrast, the account presented here is purely synchronic, with emphasis placed such notions as cate- gory, domain and construal. Secondly, Riddle’s analysis is restricted mainly to two nominal suffixes, and so does not pro- vide a general view of the subject of rivalry. By contrast, the current account covers all prefixes denoting the notion of high degree, and so offers a greater overview of the subject of rivalry. By having the right tools at its disposal, it is hoped that the current account will be able to provide an in-depth analysis of the degree-denoting prefixes and consequently solve the riddles surrounding their uses. The Present Analysis The present analysis aims to provide a new analysis of pre- fixes of degree in English, as introduced in Hamawand (2011). As the basis for the analysis, I adopt two approaches. Theoreti- cally, I utilise Cognitive Semantics and attempt to substantiate some of its tenets with reference to degree-denoting prefixes. One tenet is that linguistic items are meaningful. On this basis, I argue that a degree-denoting prefix has meanings of its own and adds substance to the host root. A degree-denoting prefix forms a category subsuming all its meanings which gather around a central sense. Another tenet is that the meaning of a linguistic item is best understood in terms of the domain to which it belongs. On this basis, I argue that degree-denoting prefixes form a domain which reveals their details including similarities and differences. A further tenet is that the use of an expression is determined by the particular construal imposed on its content. On this basis, I argue that the use of a derived word is the outcome of the particular construal the speaker imple- ments to describe a situation. Although word pairs evoke the same content and seemingly look alike, they differ in terms of the alternate ways the speaker construes their common content, which is represented by the root. To back up the analysis with empirical evidence, I exploit  Z. HAMAWAND 16 Corpus Linguistics. I extract the data required for the analysis from the BNC. To give an equitable description of the data, I opt for a qualitative analysis. In this type of analysis, as McEn- ery & Wilson (2001: p. 76) stress, no attempt is made to assign frequencies to the linguistic features which are identified in the data. It is not necessary to shoehorn the data into a finite num- ber of classifications. The reason for choosing this analysis is that rare phenomena receive the same amount of attention as more frequent phenomena. In the present analysis, I utilise two fundamental aspects of Corpus Linguistics, as suggested by Sinclair (1991: p. 170). One aspect pertains to concordance, which is an index of the keywords in a text along with their immediate contexts. Concordance helps one to study texts closely or analyse them in depth. In the present analysis, I ex- tract the words beginning with degree-denoting prefixes from the corpus, take a detailed look at the meaning of each prefix, and pick out the roots that allow more than one prefix. Due to absence of technical devices, I detect the pairs manually. The other aspect pertains to collocation, which is the ten- dency of certain words to occur together in a text, as in grill meat or toast bread. The information provided by the colloca- tion analysis can be used as a major source of evidence for the allocation of a specific meaning to an occurrence of a word within a stretch of text, removing thus the ambiguity surround- ing the word. Two works on collocations are relevant to the present analysis. One is Biber et al. (1998) which identifies collocates distinguishing between the adjectives big, large, and great. The other is Kennedy (1991) which concentrates on two types of collocates in analysing between and through: those that precede the preposition and those that follow it. My intent is to extend their methods to the investigation of derivatives that come from the same root. However, I differ from Biber et al. and Kennedy in that I look at functionally near-equivalent same-root words rather than separate words. The new departure for the present work resides in identifying the distinctive collo- cates associated with the members of a pair and, consequently, revealing the subtle differences in meaning between them. In what follows, I give a detailed presentation of the central tenets of Cognitive Semantics as they apply to prefixes of de- gree. Category This section answers the first question that prefixes of degree display multiple meanings, and that their meanings are related. Traditional dictionaries describe the senses of a lexical item as homonyms: items that are the same in spelling and pronuncia- tion but different in meaning. In this way, dictionaries ignore how such senses are related to one another, or how such senses are motivated. As a result, they miss the point that the meaning a lexical item has is vital in explaining the peculiarity associ- ated with its behaviour. To remedy this problem, Cognitive Semantics, as demonstrated by Lakoff (1987) and Taylor (1989), builds linguistic descriptions on the category theory. According to this theory, most lexical items are polysemous in nature in the sense of having numerous senses. A lexical item constitutes a complex network of interrelated senses. In this model, one sense, described as prototypical, serves as a stan- dard from which other senses, described as peripheral, are de- rived via semantic extensions. The senses are related to each other like the members of a family, where they share some general properties but differ in specific details. For instance, a kitchen chair is regarded as the prototype of the chair category because it possesses almost all of its features: a chair with a seat, a back and four legs. By contrast, rocking chair, swivel chair, armchair, wheelchair or high chair are regarded as the periph- ery because they possess only some of those features. The category theory is relevant in many areas of language. In Hamawand (2003a), I applied it to the description of comple- mentisers in English. In Hamawand (2007, 2008), I applied it to the description of suffixes. In Hamawand (2009), I applied it to the description of negative prefixes. In the present analysis, I extend its relevance to the description of the semantic structure of prefixes of degree. In this respect, I argue that a prefix forms a category of distinct but related senses. The distinct senses, which are related by virtue of a semantic network, are the result of a dynamic process of meaning extension. A prefix category is characterised by an intersection of properties that make up its members. The member that has all of the properties of the category and best represents it is described as prototypical. The other members that contain some, but not all, of the properties are described as peripheral. That is, the category is specified in general terms; the different members flesh out the category in contrasting ways. A member inherits the specifications of the category, but fleshes out the category in more detail. The prefix sub- forms a category. Prototypically, it is added to nouns re- ferring to position as in sub-basement, structure as in sub-fam- ily, and approximation as in sub-standard. Peripherally, it is added to nouns referring to subordination as in sub-editor. Categorisation is then a powerful tool which reveals the general properties of structures of a given kind via their relationships with one another. In what follows, I give a synchronic characterisation of each of the degree prefixes. The characterisation comprises five steps. First, I compile a list of words containing each prefix. In this regard, I rely on the instances offered in British National Corpus. The lists are not exhaustive but numerous enough to meet the characterisation. Second, I define the multiple senses of each prefix which is based on the analyses of the examples provided. To corroborate my definitions, I utilise major online dictionaries on English language such as Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Dictionary and Oxford English Dictionary. Third, I provide examples for each of the senses diagnosed. To boost the analysis, I make use of major works on derivation such as Marchand (1969), Urdang (1982) and Collins COBUILD Word Formation (1993). Fourth, I iden- tify the primary sense of each prefix, which is the sense that comes first to the mind of the speaker. Fifth, I pinpoint the mul- tiple senses that derive from it, which are arranged in terms of similarity to the prototype. The more similar the sense is, the closer it is to the prototype. Hyper- The basic sense of the prefix hyper- highlights degree. It means “having too much of the quality signalled by the root”. This sense arises when the adjectival bases are gradable. For example, a hyper-active person is a person who is abnormally active to the extent of lacking the ability to concentrate. Exam- ples of other adjectives are hyper-clear, hyper-creative, hyper- elegant, hyper-modern, hyper-natural, etc. The same meaning applies to nominal bases. For example, hypertension is abnor- mally high blood pressure. Examples of other nouns are hypercharge, hyperinflation, hyperthermia, hyperventilation, etc. The minor sense of the prefix hyper- highlights size. It means “vastly bigger than the thing signalled by the root”. This sense arises when the nominal roots are concrete. For example, a hypermarket is a huge self-service market usually situated on  Z. HAMAWAND 17 Ultra- the outskirts of a town. Most prevalantly, the prefix ultra- represents degree in physical terms. It means “lying beyond the feature given in the root”. This sense occurs when the adjectival roots are non- gradable. For example, ultra-violet rays are rays which lie be- yond the violet end of the visible spectrum. A list of other ad- jectives includes ultra-mundane space, ultra-sonic wave, etc. A graphical representation of the multiple senses of the de- gree-denoting prefix hyper- is offered in Figure 1. The solid arrow represents the prototypical sense, whereas the dashed arrows represent the semantic extensions. Mega- The prototype of the prefix mega- expresses measurement. It means ‘one million times the unit given in the root’. This sense occurs when the nominal roots are abstract, implying non-ac- tion. For example, a megabyte is, in computer technology, one million bytes. Other nouns are megahertz, megaton, megavolt, megawatt, etc. Less prevalently, the prefix ultra- represents degree in non- physical terms. It has two senses. (a) “far beyond the normal degree of the characteristic given in the root”. This sense occurs when the adjectival bases are gradable. For example, an ultra- nationalist is a person who is extremely devoted to the interests of his or her own nation. A list of other adjectives includes ultra-feminist groups, ultra-leftist backers, ultra-leftwing sup- porters, etc. (b) “transcending the limits of the trait given in the root”. This sense occurs when the adjectival bases are gradable. For example, an ultramodern home is a home that extremely modern or up-to-date. A list of other adjectives includes ul- tra-chic jeans, ultra-confident people, ultra-loyal customers, ultra-modest stars, ultra-smart softwares, etc. The periphery of the prefix mega- contains two extensions. (a) “greater than the example given in the root”. In this use, it expresses degree, describing an entity as being impressive. This sense occurs when the nominal roots are abstract, implying action. For example, a mega-show is a huge event in which exhibitors, entertainers or presenters take part. Other nouns are mega-business, mega-crash, mega-event, mega-tour, mega-trip, etc. (b) “bigger than the thing given in the root”. In this use, it expresses size, describing an object as being considerably large. This sense occurs when the nominal roots are concrete. For example, a megaphone is a devic e for amplify ing and direc ting the voice. Other nouns are mega-church, mega-dose, mega- drum, mega-market, mega-temple, etc. A graphical representation of the multiple senses of the de- gree-denoting prefix ultra- is offered in Figure 3. The solid arrow represents the prototypical sense, whereas the dashed arrows represent the semantic extensions. Super- The predominant sense of the prefix super- is one of degree. It subsumes three particularities. (a) “beyond the range of the trait mentioned in the root”. This sense occurs when the adjec- tival bases are gradable, applying to humans. For example, a A graphical representation of the multiple senses of the de- gree-denoting prefix mega- is offered in Figure 2. The solid arrow represents the prototypical sense, whereas the dashed arrows represent the semantic extensions. The suffix hyper- rototype degree eripher size having too much far beyond the nor Figure 1. The semantic network of the degree-denot i ng p r ef ix h y per-. The suff ix mega- rototype measurement periphery one million times greater than the ex ampl e igger than the th i ng Figure 2. The semantic network of the degree-denot i ng p r ef ix m e ga -.  Z. HAMAWAND 18 The suff ix ultra- prototype degree periphery degree lying beyond far be yond the nor m transcending the limits Figure 3. The semantic network of the degree-denot i ng p r ef ix u l tra-. superhuman effort is an effort that is much greater than is nor- mal. Similar adjectives are super-active, super-clever, super- friendly, super-intelligent, super-rich, etc. (b) “exceeding the norms of the feature mentioned in the root”. This sense occurs when the adjectival roots are gradable, applying to non-humans. For example, a super-cheap article is an article that is ex- tremely cheap. Similar adjectives are super-efficient, super- modern, super-precious, super-quick, super-secure, etc. (c) “being greater in power than the thing mentioned in the root”. This sense occurs when the nominal bases are common per- sonal nouns. For example, a super-model is a model who is very successful or famous. Similar nouns are super-athlete, super-genius, super-hero, super-leader, super-man, etc. In the periphery, the prefix super- subsumes three particu- larities. (a) “hugely bigger in size than the thing signalled by the root”. This sense occurs when the nominal bases are con- crete, denoting inanimate entities. For example, a supertanker is a very large cargo ship able to carry a large amount of oil. Similar nouns are super-ferry, super-jumbo, supermarket, su- per-computer, superpower, etc. (b) “built on the thing men- tioned in the root”. This sense occurs when the nominal roots are abstract, denoting inanimate entities. For example, a super- structure is a structure built on top of something else. Similar nouns are superaltar, superscript, supermarine, supe rstratum, supertax, etc. (c) “ranked higher than the category mentioned in the root”. This sense occurs when the nominal roots are abstract, denoting animate entities. For example, a superorder is a cate- gory of biological classification ranking above an order. Similar nouns are superclass, superfamily, superspecies, etc. A graphical representation of the multiple senses of the de- gree-denoting prefix super- is offered in Figure 4. The solid arrow represents the prototypical sense, whereas the dashed arrows represent the semantic extensions. Sur- The prototypical meaning of the prefix sur- signifies degree. It means “exceeding the amount given in the root”. This sense occurs in nominal bases. For example, a surtax means a tax charged at a higher rate than the normal rate, on income above a particular level. Similar nouns are surcharge, surplus, surreal, etc. The peripheral meaning of the prefix sur- signifies location. It subsumes two particularities. (a) “over or above the thing given in the root”. This sense occurs in nominal bases. For ex- ample, a surcoat means a piece of clothing without sleeves, worn in the past over a suit of armour. Similar nouns are sur- name, surprint, surtitiles, etc. (b) “the top of the thing given in the root”. This sense occurs in nominal bases. For example, a surface means the top layer of something, e.g. an area of water or land. A graphical representation of the multiple senses of the de- gree-denoting prefix sur- is offered in Figure 5. The solid arrow represents the prototypical sense, whereas the dashed arrows represent the semantic extensions. Before going any further, let us draw some conclusions from the preceding discussion about the prefixes of degree. One con- clusion is that each prefix forms a category of its own, which includes its multiple senses. Another conclusion is that the senses of a prefix gather around one representative sense, re- ferred to as the prototype. A further conclusion is that the cate- gory of a prefix is a powerful conceptual framework which allows us to see how the different senses are related to one another. A look at the categorial descriptions of the prefixes shows where the senses converge and where they diverge. On the basis of the converging senses, the prefixes can be grouped into a set, referred to as a domain. It is within this domain that the prefixes can stand against each other as rivals. So, a domain is concerned with a knowledge configuration in which prefixes gather showing similarity on the surface but dissimilarity below the surface. Two prefixes may stand for one concept but differ in the specifics. This cognitive tenet will be elaborated on in the next section. Domain This section answers the second question that prefixes of de- gree have distinct meanings which contrast sharply with one another. Traditional dictionaries describe the lexicon by allot- ting the lexical items of any language separate entries, with information about meaning, usage or register. In this way, dic- tionaries fail to show that many of these items have something in common as well as something in difference. As a result, dictionaries stop short of showing how they are related to one another. To solve this problem, Cognitive Semantics, as dem- onstrated by Langacker (1987, 1991), builds linguistic descrip- tions on the domain theory. The theory centres around the idea that the meaning of a lexical item can best be described with reference to the domain to which it belongs. A domain is a knowledge structure with respect to which the meaning of a lexical item can be characterised. A domain comprises a set of lexical items related in such a way that to understand the meaning of any one item it is necessary to understand the con- ceptual knowledge that it evokes. The meaning of any lexical item can be defined in terms of the background knowledge that  Z. HAMAWAND 19 The suff ix super- rototype degree periphery eyond the range exceeding the norms eing greater igger in size built on ranked higher Figure 4. The semantic network of the degree-denoting pr ef ix su per-. The suffix sur- rototype degree eripher location exceeding the amount over o above the top of sth Figure 5. The semantic network of the degree-denot i ng p r ef ix s u r-. underlies its usage. For example, in describing the meaning of the word father, the speaker needs to activate the domain of kinship as the background knowledge for his description. The domain theory is significant to all areas of language. In Hamawand (2003b), I applied it to the description of verbs taking for-to complement clauses in English. In Hamawand (2007, 2008), I applied it to the description of suffixes. In Hamawand (2009), I applied it to the description of negative prefixes. In the present analysis, I utilise it in the description of positive prefixes. The meaning of a prefix depends on the do- main to which it belongs, knowledge of which is necessary for its appropriate use. A domain is used as a cognitive device which allows one to describe the distribution of different pre- fixes and provide the motivation for their use in discourse. In this regard, I argue that the prefixes hyper-, mega-, super-, sur- and ultra- form a domain denoting degree so that to understand the semantic structure of any prefix it is necessary to under- stand the properties of the set in which it occurs as well as the properties of the other members of the set. The interpretation of a prefix can then be defined against the domain of degree which it invokes. The membership of the prefixes in the domain is based on their definitions. The meaning of a prefix arises from its relations of similarity and contrast with other prefixes in the domain. A domain is then a powerful mechanism which reveals specification and guides usage. The domain of degree is a conceptual area referring to a stage in a scale of level or extent. It signals the relative grade or volume of something especially when compared with other things. As the definition reveals, degree consists of two main facets: grade or volume. Grade refers to the calibre or quality of an entity, be it animate or inanimate. The quality is in excess; it is much more than reasonable and goes far beyond the limit of what is acceptable. The facet can either refer to human emo- tions, whose degree exceeds what is normal, or to human be- liefs, whose degree exceeds what is natural. Volume, by con- trast, refers to the amount or quantity of something which is mostly inanimate. The quantity is extreme; it is very large in amount and goes beyond what is usual. The facet can either refer to events, whose degree exceeds what is regular, or to objects, whose degree exceeds what is expected. Morphologically, the domain of degree is marked by the pre- fixes hyper-, ultra-, super-, mega-, and sur-. Although the pre- fixes denote degree, they are not interchangeable. Grade or quality is marked by the prefixes hyper-, ultra-, and super-. Hyper- means “having too much of the quality signalled by the root”. When applied to people, it describes their emotional reactions as being beyond what is tolerable. Ultra- means “far beyond the normal degree of the characteristic given in the root”. When applied to people, it describes their mental reac- tions as being beyond what is proper. Of the two, hyper- is greater than ultra- in terms of degree. Super- means “exceeding the norms or limits of the feature mentioned in the root”. When applied to products or materials, it describes their quality as being extraordinary, freak or unusual. Volume or quantity is marked by the prefixes mega- and sur-. Mega- means ‘surpass- ing the example given in the root’. When applied to events,  Z. HAMAWAND 20 their performers or their outcomes it describes them as being phenomenal, unique or exceptional. Sur- means “exceeding the amount given in the root”. Applied to things, it describes them as being additional or extra. Of the two, mega- is greater than sur- in terms of degree. Let us now scrutinise some examples to see if the prefixes serve different purposes within the domain. 1) a) hypercritical, hyper-cautious, hyper-alert. b) ultra-conservative, ultra-left, ultra-right. c) superfine, supercheap, super-efficient. d) mega-hit, mega-tour, mega-deal. e) surplus, surtax, surcharge. The examples under (1) contain words formed by adding prefixes to adjectival (a-c) and nominal (d-e) free morphemes. They present two aspects of the prefixes. First, the prefixes denote degree. Second, the prefixes embody different facets. In (1a), the prefix hyper- derives adjectives which highlight emotional traits. For examnple, hypercritical means “unrea- sonably critical by criticising others too severely or too much”. In (1b), the prefix ultra- derives adjectives which highlight political beliefs. For example, ultra-conservative means “con- servative to an extreme by having very preservative views”. In (1c), the prefix super- derives adjectives which characterise articles, especially of merchandise. For example, superfine means “very elegant and of exceptional quality”. In (1d), the prefix mega- derives nouns which characterise events, espe- cially of entertainment. For example, mega-hit means “exceed- ingly successful by achieving widespread popularity and huge sales”. In (1e), the prefix sur- derives nouns which characterise additional quantities. For example, surplus means “the extra amount which is left when requirements have been met”. For easy reference, I summarise in the Table 1 the (sub)do- mains evoked by degree-denoting prefixes in English. In the table drawn above, I show how the domain theory ap- plies to the description of prefixes in English. The description comprises four steps. In the first step, I place the prefixes under one domain, which I name degree. In the second step, I group the prefixes into two facets, which I name grade and volume. This is done relative to the definitions provided in the previous section. In the third step, I identify the prefixes that represent each facet. In the fourth step, I explain the rivalry between the prefixes by pinpointing the peculiarity of each prefix which makes it different from its counterpart. When and how to use a prefix is a matter decided by the speaker. The choice of the speaker comes under the rubric of construal. Construal is con- cerned with the ways the speaker conceives a situation and the right expressions he chooses to realise them. Two prefixes that stand as rivals construe a situation in different ways. The elaboration of this cognitive tenet will be the task of the fol- lowing section. Construal This section answers the third question that derivatives formed from the same root, but with different prefixes of de- gree, are semantically distinct from one another. Traditional dictionaries describe lexical pairs that look alike as synony- mous. Formalist paradigms regard them as an idiosyncrasy of the lexicon and often present them as semantic alternatives. In this way, formalist paradigms disregard the fact that every lexical item has a certain mission to achieve in discourse. Lexical items are in no way interchangeable even if they look similar. To improve the situation, Cognitive Semantics, as de- monstrated by Langacker (1987, 1991), builds linguistic de- scriptions on the construal theory. Construal is a language strategy which allows the speaker to conceptualise a situation and choose the linguistic structure to represent it in discourse. In Cognitive Semantics, the meaning of a linguistic expression, as Langacker (1997: pp. 4-5) states, does not reside in its con- ceptual content alone, but includes the particular way of con- struing that content. The constructions He sent a letter to Susan, and He sent Susan a letter share similar wording, but they in- volve different ways of construing the same content. In the preposi- tional construction, it is the issue of movement that is fore- grounded, whereas in the ditransitive construction it is the result of the action that is foregrounded. Therefore, only the second construction implies that Susan has received the letter. The construal theory is present in almost every area of a lan- guage. In Hamawand (2002), I applied it to the description of complement clauses in English. In Hamawand (2007, 2008), I applied it to the description of suffixes. In Hamawand (2009), I applied it to the description of negative prefixes. In the present analysis, I extend its impact to the description of positive pre- fixes. In this connection, I argue that the choice of a derived word correlates with the particular construal imposed on its root. At first sight, pairs may appear to be synonymous. A closer look, however, reveals that they are neither identical in mean- ing nor interchangeable in use. There is a clear-cut distinction in their definitions. There are two keys to using these words correctly. One key is to know that the two words constitute different conceptualisations of the same situation. The different conceptualisations reflect different mental experiences of the speaker. The other key is to know that, as a result, the two words are realised morphologically differently. In each deriva- tional case, it is the degree-denoting prefix that encodes the intended conceptualisation. The different prefixes, therefore, single out different aspects of the meaning of the root. Such pairs, if ever mentioned in dictionaries, are listed with- out clear distinction. Dictionaries confirm that they are inter- changeable. Usage books often present such pairs as reciprocal words. However, database evidence shows that they are differ- ent in use. It is true they share a common root, but they are far from being equal. The derived words relate to the slightly dif- ferent aspects of the root. The difference is a matter of the al- ternate ways the root is construed, which is morphologically mirrored by different prefixe s. The construal that is at work here is called perspective. According to Langacker (1988: p. 84), Table 1. The facets evoked by degree-denoting p refixes in English. domain Facets exponents meaning differences degree grade Hyper- ultra- super- describes people’s em otio nal reactions as being beyond what is tolerabl e describes people’s menta l reactions as be ing beyond what is proper describes the quality of products or materials as being extraordinary volume Mega- sur- describes events, their performers or their outcomes as being exceptiona l describes things as being additional or extra  Z. HAMAWAND 21 it refers to the specific viewpoint imposed on a scene, which changes according to the position from which one is consider- ing it. Two expressions differ in meaning depending on which aspects within the situation they designate. In addition, speakers have the ability to construe the same situation in many ways and choose the appropriate structures to represent them. Con- sequently, the perspective embodied by a linguistic expression constitutes a crucial facet of its meaning. For the pair list, I rely on the data provided by the BNC. To create the list, I compare the occurrences of two prefixes with a view to finding the words that share the same root. The lists of pairs are not exhaustive but numerous enough to reflect the meaning differences between the derived words. For the defini- tions of the common roots of the pairs, I rely on such major online English dictionaries as Oxford English Dictionary, Cam- bridge English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster Dictionary. For the exemplification of the meanings diagnosed, I provide sentences based on the corpus. In most cases, I tend to shorten the sentences by deleting all the non-essential elements. For the sake of reinforcement, I check the characterisation of some pairs, if ever mentioned, against major manuals on English usage like Fowler (1996), Patridge (1961), Greenbaum & Whit- cut (1988), and Peters (2004). Below are the different perspectives taken on the roots, which are responsible for the semantic distinctions. Excessive vs Extreme The prefixes hyper-, ultra- and super- form adjectival trebles from common adjectival roots. They evoke the domain of de- gree, but they represent different facets of it. The prefixes hy- per- and ultra- describe quality as being excessive, exceeding what is reasonable or tolerable. The prefix hyper- means “hav- ing too much of the quality signalled by the root”. It shows that the quality stated is immoderate. The prefix ultra- means “lying beyond the feature given in the root”. It shows that the quality stated is inordinate. Mostly but not always, the two prefixes have negative connotations. The prefix super- describes quality as being extreme, exceeding what is usual or proper. It means “exceeding the norms or limits of the feature mentioned in the root”. It describes the feature as being more than normal. The prefix has positive connotations. A consideration of the data bears out the differences in their application. Hyper- applies to people or their reactions to certain stimuli. Ultra- applies to procedures of carrying out particular tasks. Super- applies to equipment or their advantages. A typical indication of this dis- tinction is offered by the adjectival examples below: 2) hypersensitive vs ultrasensitive vs supersensitive a) She’s hypersensitive to any form of criticism. b) They use an ultra-sensitive technique to measure resid- ual disease. c) They manufacture supersensitive musical instruments. The adjectives in (2) are derived from the adjectival base sensitive, meaning “reacting quickly or more than usual to something”. Despite this, construal draws a line of demarcation between them. In (2a), the adjective hypersensitive means “ex- cessively sensitive”. A hypersensitive person is a person who reacts very badly to rude remarks or specific substances. Words associated with hypersensitive denote emotions such as criti- cism, insult, offence, stress, unease; chemical substances such as agent, caffeine, drug, medication, therapy; aspects of things such as colour, light, noise, smell, sound, etc. In (2b), the adjec- tive ultrasensitive means “abnormally sensitive”. An ultrasensi- tive object is an object that is beyond what is proper or moder- ate. Words associated with ultrasensitive imply procedures such as assay, device , mechanism, system, technique, etc. In (2c), the adjective supersensitive means “extremely sensitive”. A super- sensitive detector is a detector that is extremely sensitive in discovering the presence of something, such as metal, smoke, explosives or changes in pressure or temperature. Words asso- ciated with supersensitive name devices such as detector, in- strument, receptor, scanner, tool, etc. Quality vs Quantity The prefixes super- and mega- form nominal pairs from common nominal roots. They elicit the domain of degree, but they underline distinguishable aspects of it. The prefix super- marks quality, the distinctive attribute or characteristic of an entity. It means means ‘being greater in power than the thing mentioned in the root’. In describing individuals from a per- formance perspective, it means extraordinary, i.e. someone is extremely remarkable, unusual or prominent in a profession. The prefix mega- marks quantity, the property of an entity that is measurable in number, amount, size or weight. It means “surpassing the example given in the root”. In describing indi- viduals from an economic perspective, it means phenomenal, i.e. someone is extremely successful, superior or unequalled in his/her field. An investigation of the data confirms the differ- ences in their focus. Super- focuses on class or calibre, whereas mega- focuses on amount or volume. A pertinent illumination of this distinction is afforded by the nominal pair below: 3) superstar vs megastar a) He spoke about the pressures of being a superstar. b) The megastar is earning bucket loads of money. The two nouns in (3) are derived from the nominal root star, meaning “an outstanding person or thing”. Both refer to an ex- tremely famous person in the fields of film, music, sports, etc. In spite of sharing the same root and having similar definitions, they are construed differently in discourse. In (3a), the noun superstar means “a well-known personality”. A superstar is an extremely famous performer. The contextual preferences of superstar are words denoting quality such as achievement, per- formance, pressure, style, success, etc. In (3b), the noun mega- star means “a well-known celebrity”. A megastar is a very fa- mous entertainer. The contextual preferences of megastar are words denoting quantity such as cash, money, revenues, stakes, wealth, etc. In short, although superstar and megastar might be defined as “an extremely famous performer”, they tend to occur in different contexts. Conclusion This paper has attempted to resolve the inconsistencies found in dictionaries and the literature concerning the semantic nature of prefixes of degree. Precisely, it has atte mpted to demonstr ate the possibility of grouping the prefixes in a set, and to resolve the semantic differences between pairs of words that share the same root but begin with different prefixes. Such pairs have not been explained in minute detail or covered in a systematic manner. Precisely, the analysis is aimed at detecting the dis- cernible patterns that govern the distribution of prefixes and the words they form in English. In doing so, the analysis has a beneficial effect on lexicographers and morphologists by shed- ding light on cases of alternation between such pairs of words in exemplary sentences drawn form authentic data. To solve the problem, I have made three arguments. One ar- gument is that the prefixes are polysemous in nature, where a prefix is associated with a number of related but distinct senses.  Z. HAMAWAND 22 The senses of a prefix constitute a semantic network organised around a primary sense component called a prototype. The prototype, in turn, interacts with a constrained set of cognitive principles to derive a set of additional distinct senses. The dis- tinct senses which fit the scenes being described reflect the speaker’s experiences of the world. Consequently, the lexicon constitutes a network of form-meaning associations, not an arbitrary repository of unrelated lexemes, as claimed by the generative paradigm. A second argument is that the prefixes gather in a domain, where each prefix designates a particular facet of a domain. The prefixes hyper-, ultra- and super- carve up the facet of grade, but each represents a particular dimension of it. The prefix hyper- means “having too much of the quality signalled by the root”. It describes people’s emotional reactions as being beyond what is tolerable. The prefix ultra- means “far beyond the nor- mal degree of the characteristic given in the root”. It describes people’s mental reactions as being beyond what is proper. The prefix super- means “exceeding the norms or limits of the fea- ture mentioned in the root”. It describes the quality of products or materials as being extraordinary. The prefixes mega- and sur- evoke the facet of volume, but each represents a particular dimension of it. The prefix mega- means “surpassing the exam- ple given in the root”. It describes events, their performers or their outcomes as being phenomenal. The prefix sur- means “exceeding the amount given in the root”. It describes things as being additional. Consequently, prefixes do not exist inde- pendently of each other, in the way foreseen by pre-cognitive theories. A third argument is that a pair sharing the same root and ending in different prefixes is not synonymous. The distinction resides in the alternate ways the pair is construed, which is realised by different morphemes. In deriving each word, the prefix shifts the meaning of the root to a certain direction, and so encodes the intended construal. This is evidenced by the distinguishing collocates of each pair member, which corpus data show. Consequently, in the choice between two or more prefixes the factor of meaning is much more explanatory than the morphological form or the syllabic structure of the root, which an analysis based on productivity claims. To back up the semantic analysis, I have used a corpus-based methodology in the analysis. The purpose is to demonstrate how the semantic contrasts are reflected in collocations of dif- ferent word classes or contextual preferences. Discriminating collocates have shown that the pairs hitherto claimed to be synonymous do pattern differently. The corpus data therefore back in a clear way the claim that meaning is more explanatory than the form of the root in the choice between rival prefixes which derive words from the same root. The examples analysed show how the language user correlates formal differences with semantic differences. In language, absolutely synonymous words hardly exist. References Aronoff, M. (1976). Word formation in generative grammar. Cam- bridge, MA: MIT Press. Aronoff, M., & Sungeun C. (2001). The semantics of -ship suffixation. Linguistic Inquiry, 32, 167-173. doi:10.1162/002438901554621 Beard, R. (1995). Lexeme-morpheme base morphology. New York: State University of New York Press. Biber, D., Susan C., & Randi R. (1998). Corpus linguistics: Investigat- ing linguistic structure and use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. BNC. British National Corpus. http://sara.natcorp.ox.ac.uk Bybee, J. (1985). Morphology: An inquiry into the relation between meaning and form. Amsterdam: Benjamins. http://dictionary.cambridge.org Chomsky, N. (1957) . Syntactic structures. The Hague: Mouton. Chomsky, N. (1965) . Aspects of the theory of syntax. Mass: MIT Press. Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris. Collins, C. (1993). Word Formation. London: HarperCollins Publish- ers. Fowler, H. (1996). Modern English usage. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Górska, E. (1994). Moonless nights and smoke-free cities, or what can be without the other? A cognitive study of privative adjectives in English. Folia Linguistica, 28, 413-435. Górska, E. (2001). Recent derivatives with the suffix -less: A change in progress within the category of English privative adjectives. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, 36, 189-202. Greenbaum, S., & Janet W. (1988). Longman guide to English usage. Essex: Longman. Hamawand, Z. (2002). Atemporal complement clauses in English. A cognitive grammar analysis. München: Lincom. Hamawand, Z. (2003a). The construal of atemporalisation in comple- ment clauses in English. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 1, 61-87. doi:10.1075/arcl.1.04ham Hamawand, Z. (2003b). For-to complement clauses in English: A cog- nitive grammar analysis . Studia Linguistica, 57, 171-192. doi:10.1111/j.0039-3193.2003.00103.x Hamawand, Z. (2007). Suffixal rivalry in adjective formation. A cogni- tive-corpus analysis. L ondon: Equinox. Hamawand, Z. (2008). Morpho-lexical alternation in noun formation. London: Palgrave Macmill an. doi:10.1057/9780230584013 Hamawand, Z. (2009). The semantics of English negative prefixes. London: Equinox. Hamawand, Z. (2011). Morphology in English. Word formation in cognitive grammar. London: Co ntinuum. Kennedy, G. (1991) . Between and through: The company they keep and the functions they serve. In K. Aijmer and B. Altenberg (Eds.), Eng- lish Corpus Linguistics: Studies in honour of Jan Svartvik (pp. 95-110). London : Longma n. Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Langacker, R. (1987). Foundations of cognitive grammar. Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Langacker, R. (1988). A view of linguistic semantics. In B. Rudzka- Ostyn (Ed.), Topics in Cognitive Linguistics (pp. 49-90). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Langacker, R. (1990). Subjectification. Cognitive Linguistics, 1, 5 -38. doi:10.1515/cogl.1990.1.1.5 Langacker, R. (1991). Foundations of cognitive grammar. Vol. 2: De- scriptive application. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Langacker, R. (1997). Consistency, dependency and conceptual group- ing. Cognitive Linguistics, 8, 1-32. doi:10.1515/cogl.1997.8.1.1 Lieber, R. (2004). Morphology and lexical semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511486296 Marchand, H. (1969). The categories and types of present-day English word formation. A Synchronic- d ia chronic appro a ch. Munich: Beck. McEnery, T., & Andrew W. (2001). Corpus linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Universi ty Press. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. http://www.m-w.com. Oxford Collocations Dictionary: For students of English. (2003). Ox- ford: Oxford University Press. Oxford English Dictionary Online. http://www.oed.com Patridge, E. (1961). Usage and abusge. A guide in good English. Lon- don: Hamish Hamilton. Peters, P. (2004). The Cambridge guide to English usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511487040 Plag, I. (1999). Morphological productivity. Structural constraints in English derivation. Berlin: Mouto n d e Gruyter. Riddle, E. (1985). A historical perspective on the productivity of the suffixes -ness and -ity. In J. Fisiak (Ed.), Historical Semantics His- torical Word-Formation (pp. 435- 461). Berlin: Mouton Publishers. Selkirk, E. (1982). The Syntax of words. Cam bridge, MA: MIT Press.  Z. HAMAWAND 23 Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance and collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Spencer, A. (2001). Morphology. In M. Aronoff and J. Rees-Miller (Eds.), The Handbook of Linguistics (pp. 213-237). Malden, MA: Blackwell. Taylor, J. (1989). Linguistic categorisation. Prototypes in linguistic theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Urdang, L. (1982). Suffixes and other word-final elements of English. Detroit: Gale Research Company.

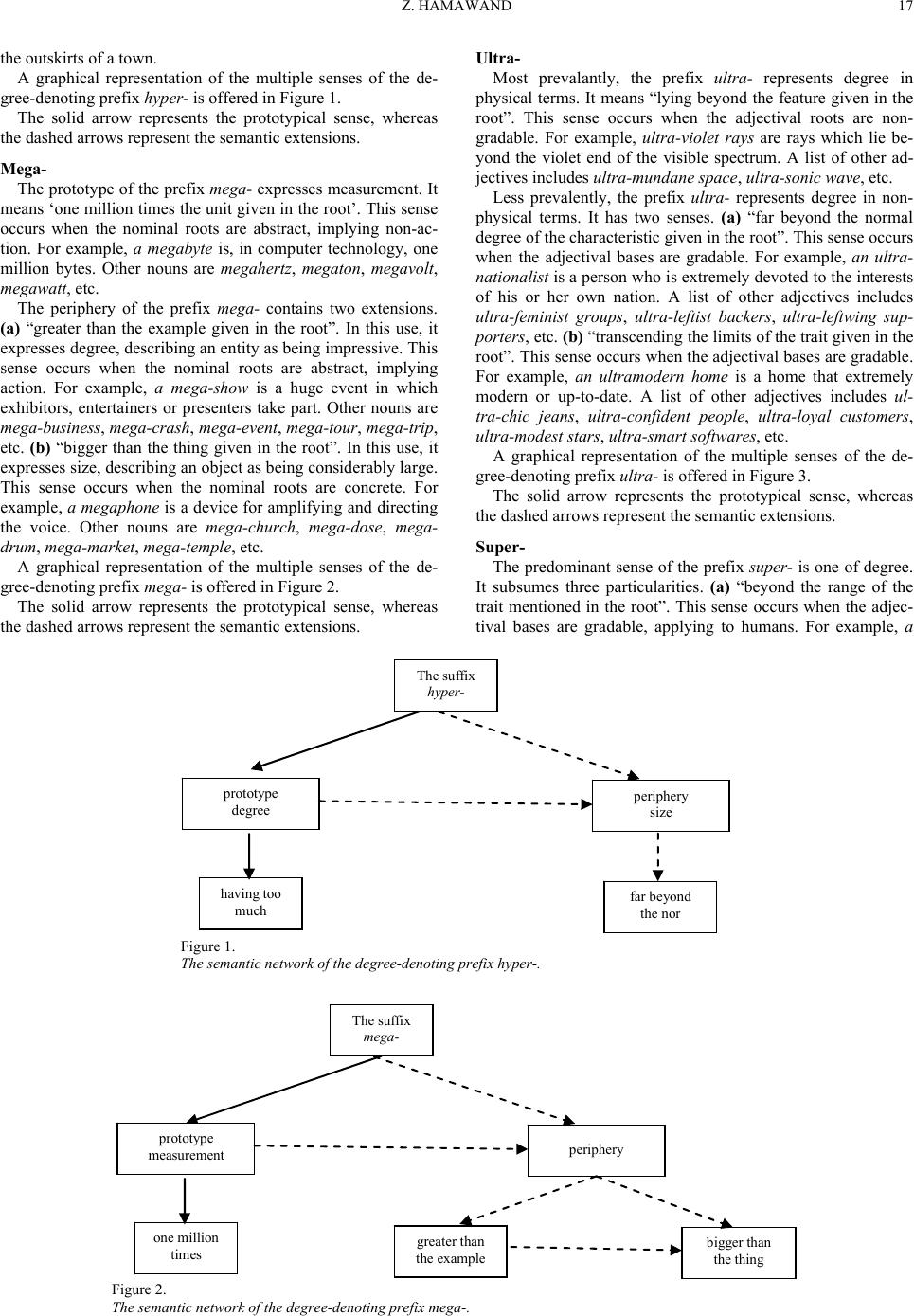

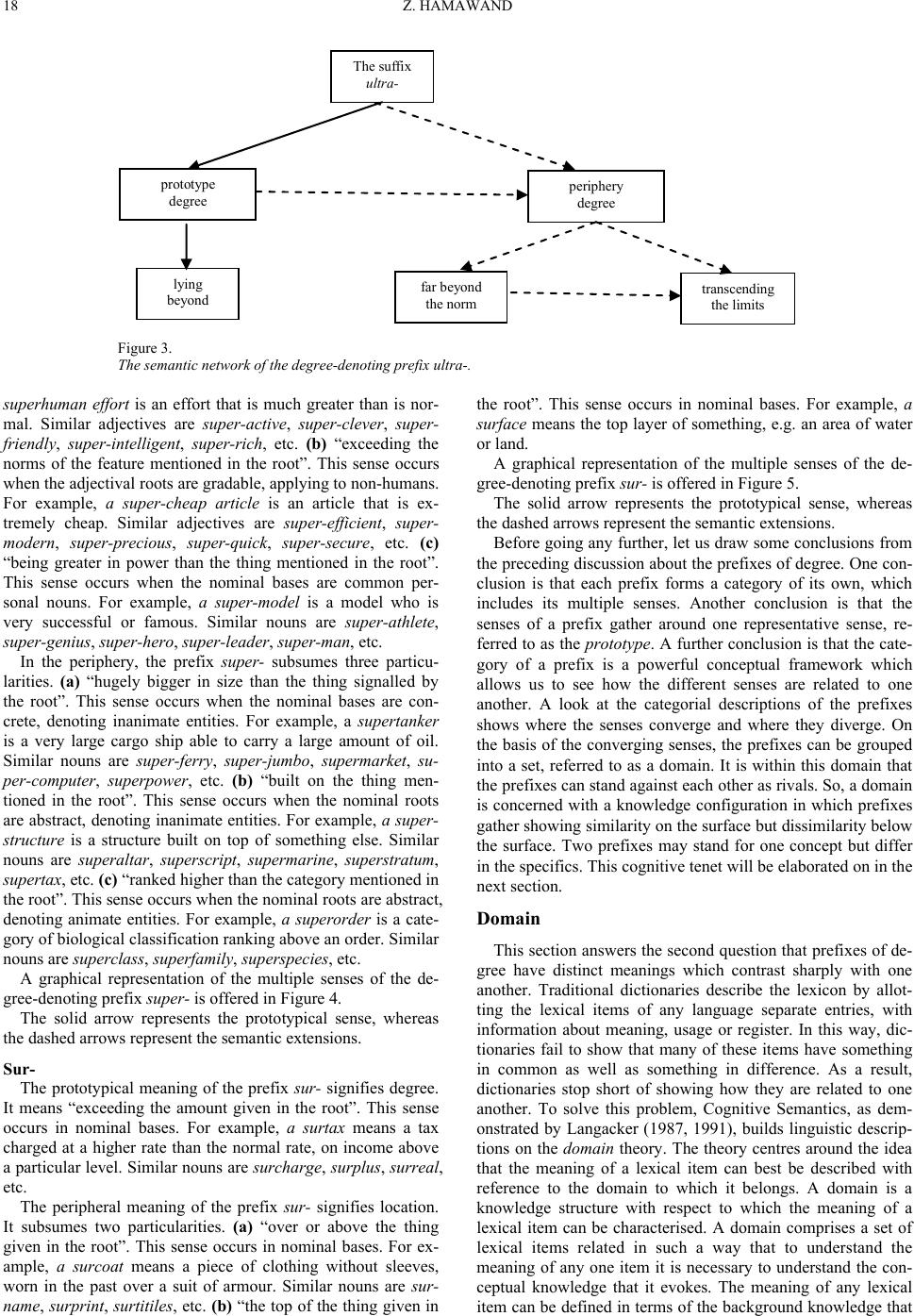

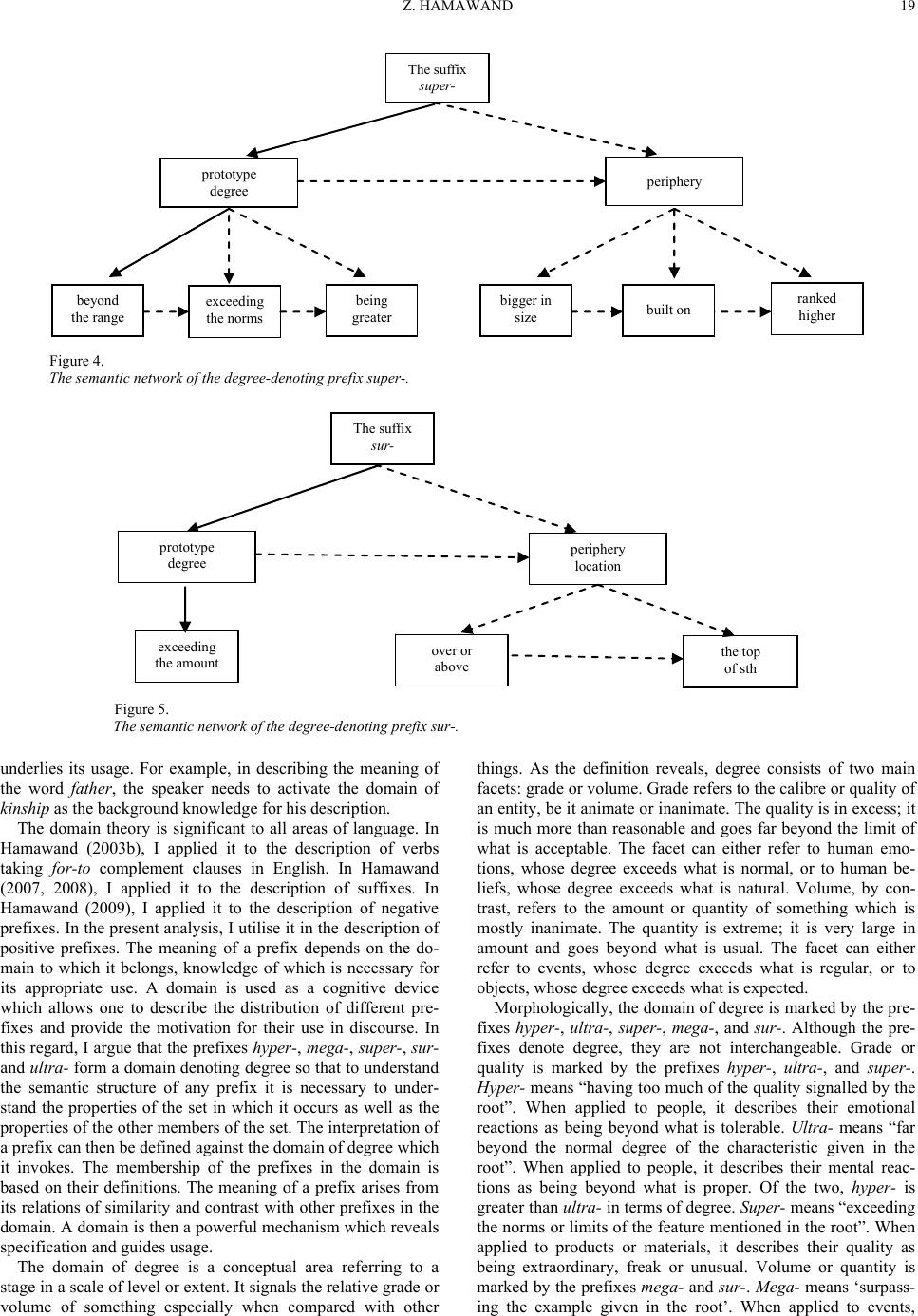

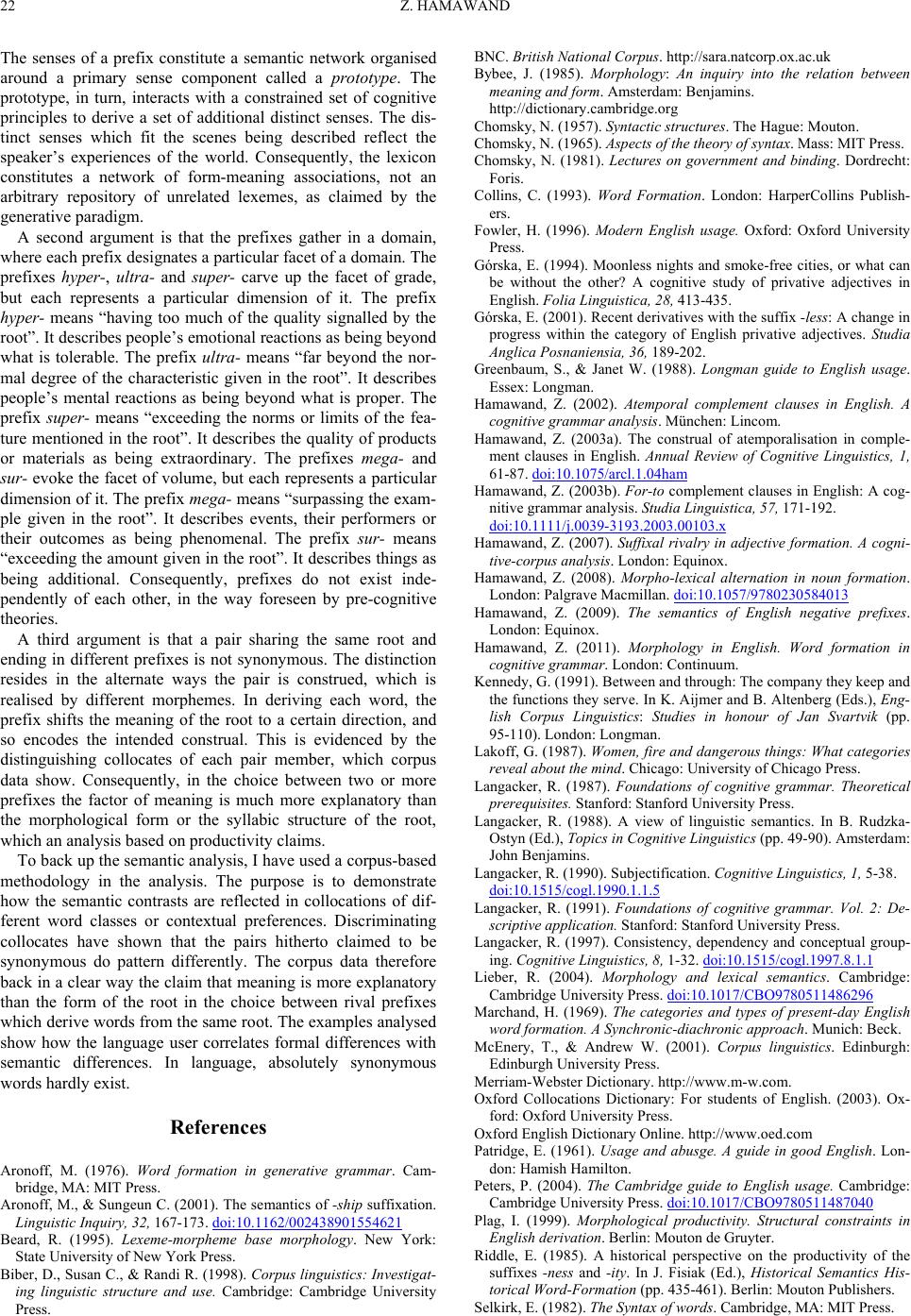

|