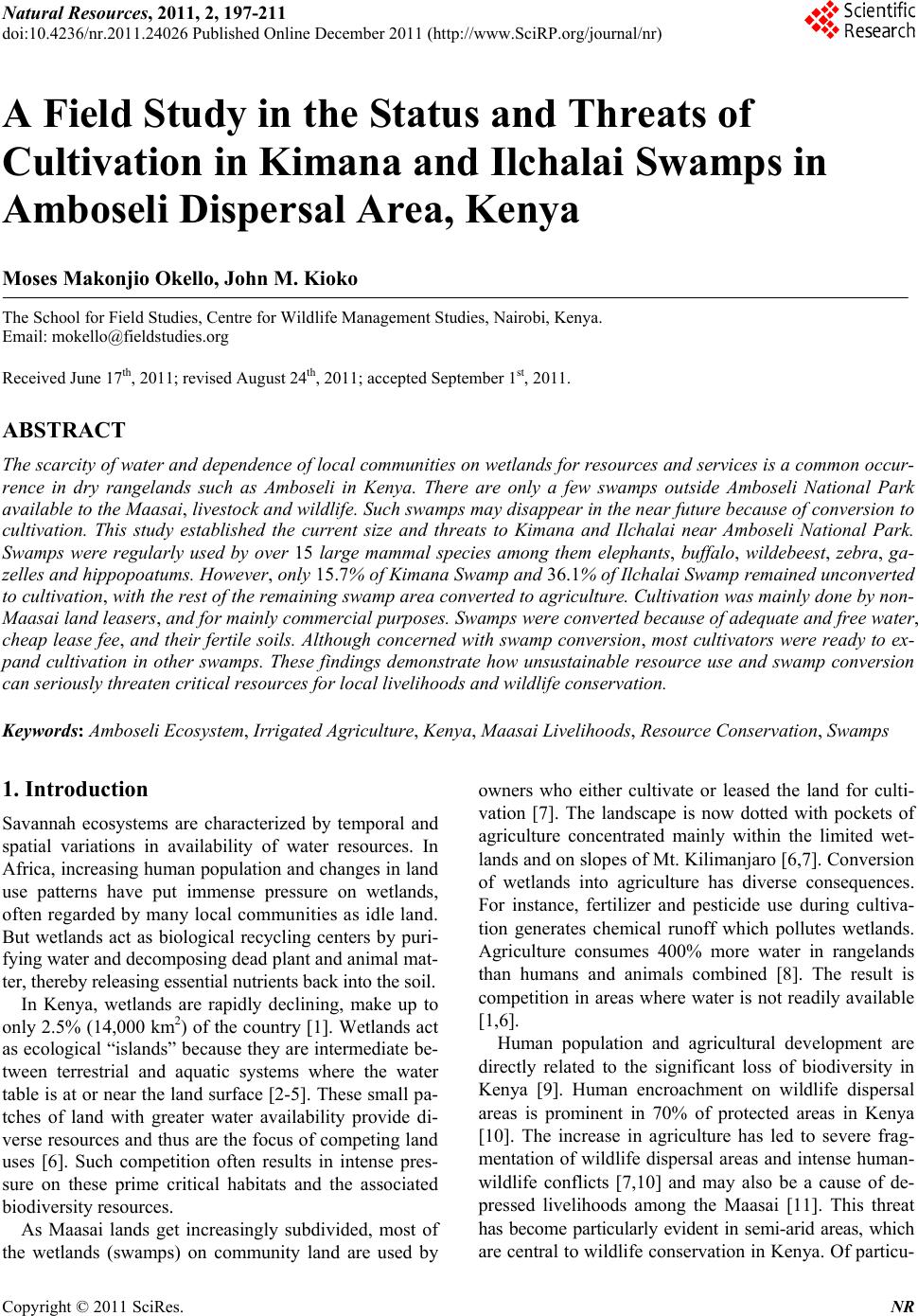

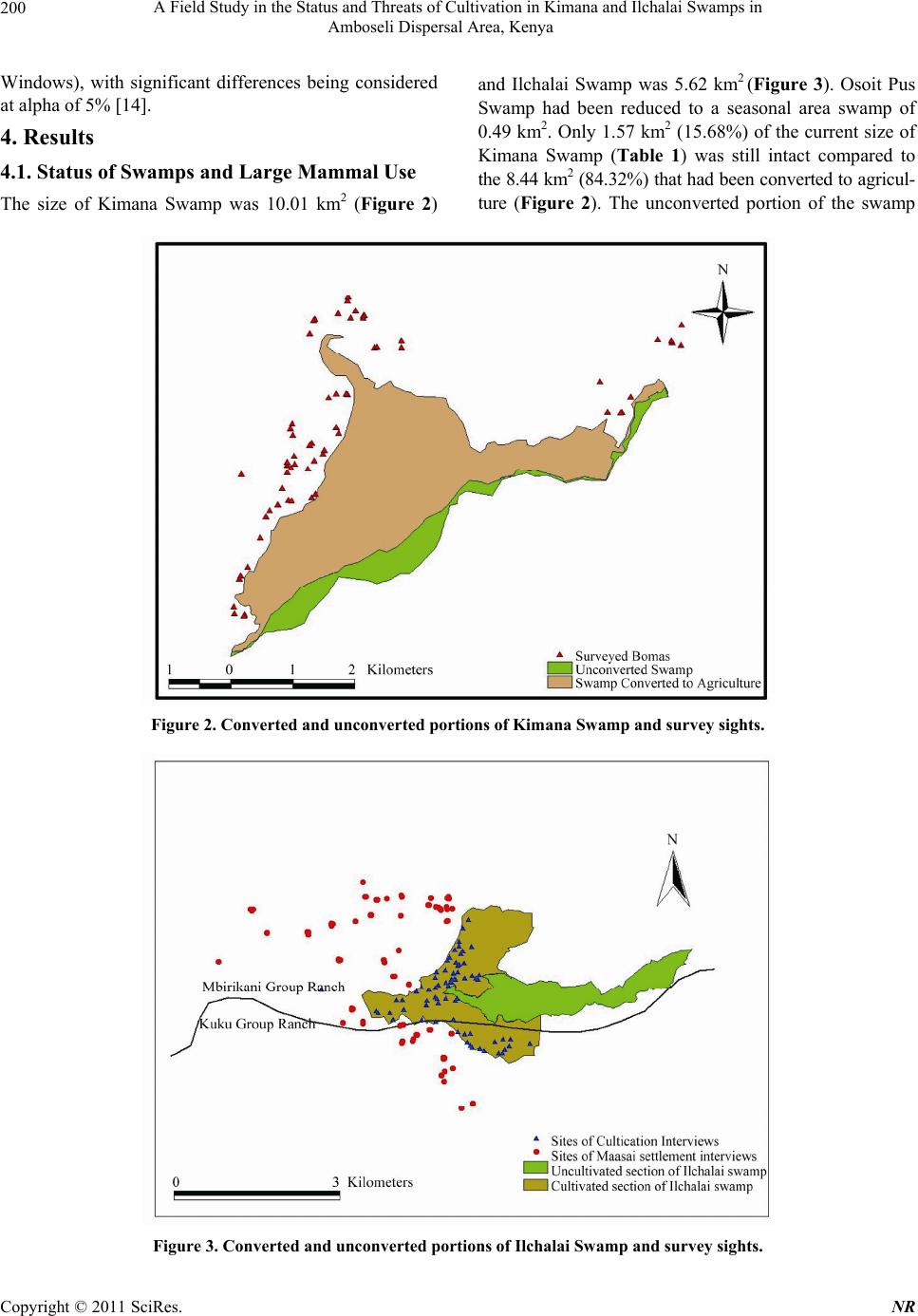

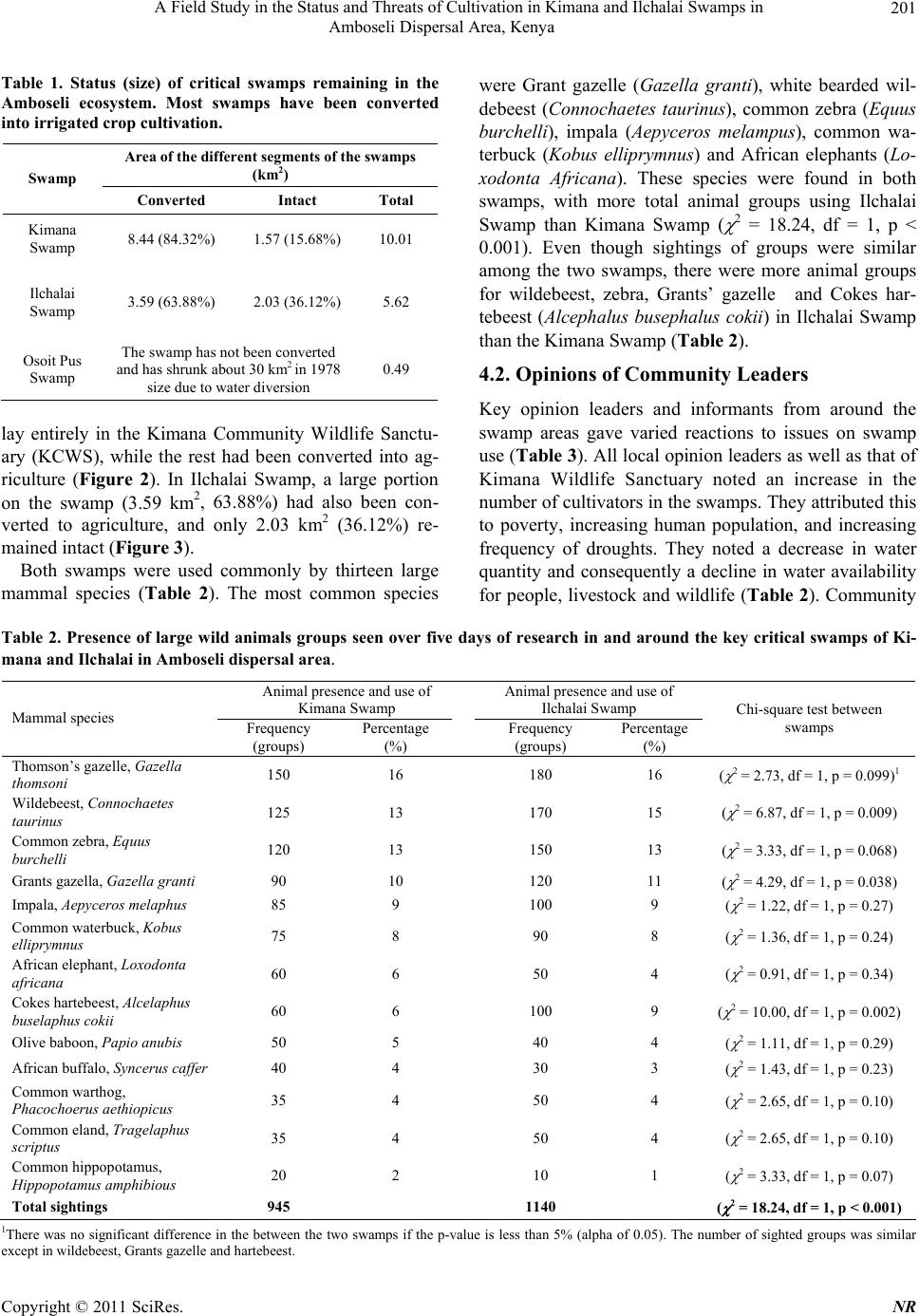

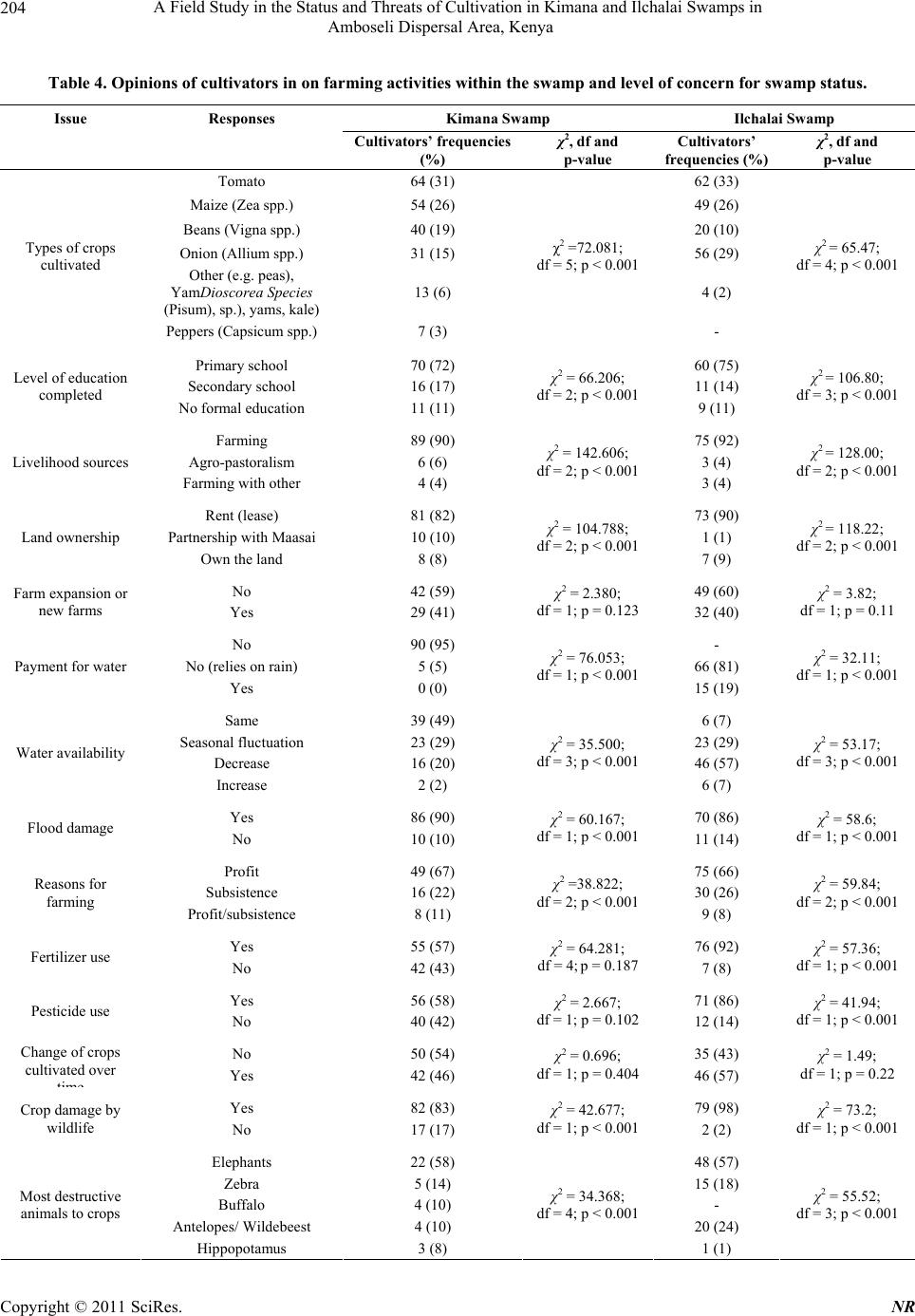

Natural Resources, 2011, 2, 197-211 doi:10.4236/nr.2011.24026 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/nr) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Moses Makonjio Okello, John M. Kioko The School for Field Studies, Centre for Wildlife Management Studies, Nairobi, Kenya. Email: mokello@fieldstudies.org Received June 17th, 2011; revised August 24th, 2011; accepted September 1st, 2011. ABSTRACT The scarcity of water and dependence of local communities on wetlands for resources and services is a common occur- rence in dry rangelands such as Amboseli in Kenya. There are only a few swamps outside Amboseli National Park available to the Maasai, livestock and wildlife. Such swamps may disappear in the near future because of conversion to cultivation. This study established the current size and threats to Kimana and Ilchalai near Amboseli National Park. Swamps were regularly used by over 15 large mammal species among them elephants, buffalo, wildebeest, zebra, ga- zelles and hippopoatums. However, only 15.7% of Kimana Swamp and 36.1% of Ilchalai Swamp remained unconverted to cultivation, with the rest of the remaining swamp area converted to agriculture. Cultivation was mainly done by non- Maasai land leasers, and for mainly commercial purposes. Swamps were converted because of adequate and free water, cheap lease fee, and their fertile soils. Although concerned with swamp conversion, most cultivators were ready to ex- pand cultivation in other swamps. These findings demonstrate how unsustainable resource use and swamp conversion can seriously threaten critical resources for local livelihoods and wildlife conservation. Keywords: Amboseli Ecosystem, Irrigated Agriculture, Kenya, Maasai Livelihoods, Resource Conservation, Swamps 1. Introduction Savannah ecosystems are characterized by temporal and spatial variations in availability of water resources. In Africa, increasing human population and changes in land use patterns have put immense pressure on wetlands, often regarded by many local communities as idle land. But wetlands act as biological recycling centers by puri- fying water and decomposing dead plant and animal mat- ter, thereby releasing essential nutrients back into the soil. In Kenya, wetlands are rapidly declining, make up to only 2.5% (14,000 km2) of the country [1]. Wetlands act as ecological “islands” because they are intermediate be- tween terrestrial and aquatic systems where the water table is at or near the land surface [2-5]. These small pa- tches of land with greater water availability provide di- verse resources and thus are the focus of competing land uses [6]. Such competition often results in intense pres- sure on these prime critical habitats and the associated biodiversity resources. As Maasai lands get increasingly subdivided, most of the wetlands (swamps) on community land are used by owners who either cultivate or leased the land for culti- vation [7]. The landscape is now dotted with pockets of agriculture concentrated mainly within the limited wet- lands and on slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro [6,7]. Conversion of wetlands into agriculture has diverse consequences. For instance, fertilizer and pesticide use during cultiva- tion generates chemical runoff which pollutes wetlands. Agriculture consumes 400% more water in rangelands than humans and animals combined [8]. The result is competition in areas where water is not readily available [1,6]. Human population and agricultural development are directly related to the significant loss of biodiversity in Kenya [9]. Human encroachment on wildlife dispersal areas is prominent in 70% of protected areas in Kenya [10]. The increase in agriculture has led to severe frag- mentation of wildlife dispersal areas and intense human- wildlife conflicts [7,10] and may also be a cause of de- pressed livelihoods among the Maasai [11]. This threat has become particularly evident in semi-arid areas, which are central to wildlife conservation in Kenya. Of particu-  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 198 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya lar interest is the Amboseli Ecosystem; one of the main hubs of wildlife endowment in the country. The creation of protected areas, such as Amboseli, on land historically owned by Maasai is an extremely emotive issue in the area. The result is intense competition among the Maasai people, their livestock, and wildlife for limited resources, especially water resources [6]. When Amboseli was designated as a national park in 1974, it enclosed all permanent swamps used by the Maasai in the area. Only a few (such as Namelok, Ki- mana, Ilchalai and Osoit Pus Swamps) were left outside the park [12]. These swamps were not as large and as reliable as those sealed inside the park. Thus, the Maasai were forced to rely on the few swamps outside the park for watering their livestock and for critical livelihood re- sources. At the same time, the swamps were utilized by wildlife during dispersion outside Amboseli National Park. The combined effects of increasing population, changing socio-economic realities and changing land uses [6], these swamps are faced with serious threats of degrada- tion and conversion and are steadily diminishing. Of the swamps left outside of Amboseli, one of them, Namelok, has since been fenced in and is unavailable to wildlife [7]. Increased irrigation upstream and re-direct- ing of water into the Nairobi Pipeline from Nolturesh River has reduced Osoit Pus Swamp to a seasonal swamp. Only Kimana and Ilchalai swamps remain viable, but are under serious siege from irrigated agriculture. Establishing the current size of these swamps and the opinions of stakeholders using it will provide the first step in establishing strategies to prevent the complete degradation and conversion of these critical wetlands. We present a case study of the land use dynamics in Ki- mana and Ilchalai swamps that is critical to sustenance of local human livelihoods and wildlife in the area. The area is important for wildlife conservation and serves as part of wildlife dispersal area for Tsavo West, Chyulu and Amboseli National Parks, and the Kimana Commu- nity Wildlife Sanctuary. Studying the relationships among the various users will help understand the land use dy- namics within wetlands of dispersal areas and shed some light on lessons that may be applied in other dry lands of Kenya and Africa. The overall objective of this study was to establish the current size, status, threats, and perspectives of the local Maasai for two critical swamps (Kimana and Ilchalai) that lie between Amboseli National Park and Chyulu Hills/Tsavo West National Parks. The specific objectives were to map the Kimana and Ilchalai swamps to establish their current size, the area converted to irrigated agricul- ture, and the area remaining. Also to interview the local Maasai and various cultivators to establish local opinions regarding swamp resource use, threats, and future viabil- ity of these critical swamps. 2. Study Area This study was conducted in the Kimana and Ilchalai swamps (Figure 1) in the Tsavo-Amboseli ecosystem of Figure 1. The location of Kimana Swamp and Ilchalai Swamp within the group ranches in Amboseli Ecosystem. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 199 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya southern Kenya in June and July of 2006. The Kimana Swamp, located at the junction of the Kimana and Isinet Rivers, is situated on the border of Kimana and Mbiri- kani Group Ranches that form wildlife dispersal area for Tsavo West and Amboseli National Parks. Ilchalai Swa- mp, located on the Kikarankot River, lies on the boarder between Kuku Group Ranch and Mbirikani Group Ranch. The swamps are fed by underground aquifers that fed by water from Mt. Kilimanjaro and run-off during the rainy season. The elevation of the area is 1199 m above sea level. Temperatures within the area vary seasonally; highs reach 35˚C in February and March and lows 12˚C in July. Average monthly temperatures fall between 21˚C and 25˚C. Annual rainfall is concentrated into two seasons: the wet season, which ranges from November to January, and the dry season, which ranges from March to May. Total rainfall in the area averages 350 mm per year. This makes swamps in the area critical resources for wildlife, people and livestock. The seasonally flooded swamps are dominated by Cy- prus immensus, Acacia xanthophlea. Benth., Salvadora persica L., Acacia tortillis (Forssk.) Hanyne, and sur- rounded by Commiphora woodlands. The soils in the swamps include Saline orthic Solonetz and Solonchaks, as well as dispersed areas of Andosols, Chernozens, and Luvisols that form in lakebeds which are seasonally flooded [1]. African elephants (Loxodonta Africana, Blumenbanch), Plains Zebras (Equus burchelli, Gray), African Buffalos (Syncerus caffer, Fisher), Common Hippopotamuses (Hi- ppopotamus amphibious, Le Conte), Grants Gazelle (Ga- zella granti, Nanger), Common waterbuck (Kobus ellip- siprymnus, Ogibly), Thomson’s Gazelle (Gazella thomp- sonii, Nanger) and Maasai Giraffe (Giraffa camelopar- dalis, Le Conte) are some of the major wildlife that fre- quently uses the swamps, especially in the dry season [7, 13]. The Kimana Community Wildlife Sanctuary (KCWS), which is key for tourism revenue and income generation to Kimana Group Ranch members, encompasses part of the Kimana Swamp. However, Ilchalai Swamp is not under any protected status. The area is Maasai land, de- fined by group ranches, and the primary type of land use within the swamps is rain fed crop cultivation and dry season grazing area by the pastoral Maasai. 3. Methods and Materials This study relied on questionnaires and discussions with key informants to get information on local opinions on the threats and status of swamps and cultivation activities in the swamps. A combination of these two approached provided more insights and helped cross-check facts so as to ascertain their influence and authenticity. This is re- commended in all sociological PRA studies. Geographi- cal mapping was critical in providing information on the area and conversion of the wetlands so that current status on the ground was established. This was important sup- porting work for the sociological research components of this study. 3.1. Swamp Mapping Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers (Etrex Leg- end) were used to take coordinates along intact and con- verted (cultivated) sections of the swamps. Readings were taken along the entire perimeter of the swamps (en- tire swamp, intact and cultivated segments). Any wildlife species using uncultivated areas of the swamps were also noted. For the five days of research, a record of groups of large mammals were kept in for the two swamps for purposes of establishing presence of wildlife use and comparisons of group sizes. Presence in terms of number of groups rather than total number of use was the interest in this study. The GPS coordinates were then recorded on data sheets and input into Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Cor- poration, 2003). The data was transferred to ArcView 3.2 GIS (ESRI, 1999) for spatial analysis of the swamps. This was used to generate maps that depict the extent and characteristics of each swamp. 3.2. Interviews with Farmers and Local Maasai Cultivators (mostly immigrants from Northern Tanzania and other Kenyan tribes) as well as local Maasai living around the swamps were interviewed. The sampling unit was a farm or a household where household heads or farm owners were interviewed. A distinct effort was made to interview all stakeholders. Further, key opinion leaders and officials of Kimana, Kuku, and Mbirikani group ranches were also interviewed for their perspec- tives concerning resource use, threats, and the status of the swamps. A set of semi-closed questionnaires and open discussions were used to capture the opinions and to acquire information regarding the status of the swa- mps. Information was gathered regarding water avail- ability, resource use, human impacts, and use by wildlife. Research teams were accompanied by local guides who acted as translators. For Kimana swamp, 99 interviews were conducted with cultivators and 83 with Maasai households. For Ilchalai swamp, interviews were con- ducted with 81 cultivators and 90 Maasai households. A total of seven local opinion leaders were interviewed. Chi-square goodness of fit was used to determine dif- ferences in frequencies of responses on particular issues, while chi-square cross tabulations were used to establish relationships between interviewee attributes and re- sponses. This was done using SPSS® (Version 9.0 for Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 200 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Windows), with significant differences being considered at alpha of 5% [14]. 4. Results 4.1. Status of Swamps and Large Mammal Use The size of Kimana Swamp was 10.01 km2 (Figure 2) and Ilchalai Swamp was 5.62 km2 (Figure 3). Osoit Pus Swamp had been reduced to a seasonal area swamp of 0.49 km2. Only 1.57 km2 (15.68%) of the current size of Kimana Swamp (Table 1) was still intact compared to the 8.44 km2 (84.32%) that had been converted to agricul- ture (Figure 2). The unconverted portion of the swamp Figure 2. Converted and unconverted portions of Kimana Swamp and survey sights. Figure 3. Converted and unconverted portions of Ilchalai Swamp and survey sights. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 201 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Table 1. Status (size) of critical swamps remaining in the Amboseli ecosystem. Most swamps have been converted into irrigated crop cultivation. Area of the different segments of the swamps (km2) Swamp Converted Intact Total Kimana Swamp 8.44 (84.32%) 1.57 (15.68%) 10.01 Ilchalai Swamp 3.59 (63.88%) 2.03 (36.12%) 5.62 Osoit Pus Swamp The swamp has not been converted and has shrunk about 30 km2 in 1978 size due to water diversion 0.49 lay entirely in the Kimana Community Wildlife Sanctu- ary (KCWS), while the rest had been converted into ag- riculture (Figure 2). In Ilchalai Swamp, a large portion on the swamp (3.59 km2, 63.88%) had also been con- verted to agriculture, and only 2.03 km2 (36.12%) re- mained intact (Figure 3). Both swamps were used commonly by thirteen large mammal species (Table 2). The most common species were Grant gazelle (Gazella granti), white bearded wil- debeest (Connochaetes taurinus), common zebra (Equus burchelli), impala (Aepyceros melampus), common wa- terbuck (Kobus elliprymnus) and African elephants (Lo- xodonta Africana). These species were found in both swamps, with more total animal groups using Ilchalai Swamp than Kimana Swamp ( 2 = 18.24, df = 1, p < 0.001). Even though sightings of groups were similar among the two swamps, there were more animal groups for wildebeest, zebra, Grants’ gazelle and Cokes har- tebeest (Alcephalus busephalus cokii) in Ilchalai Swamp than the Kimana Swamp (Table 2). 4.2. Opinions of Community Leaders Key opinion leaders and informants from around the swamp areas gave varied reactions to issues on swamp use (Table 3). All local opinion leaders as well as that of Kimana Wildlife Sanctuary noted an increase in the number of cultivators in the swamps. They attributed this to poverty, increasing human population, and increasing frequency of droughts. They noted a decrease in water quantity and consequently a decline in water availability for people, livestock and wildlife (Table 2). Community Table 2. Presence of large wild animals groups seen over five days of research in and around the key critical swamps of Ki- mana and Ilchalai in Amboseli dispersal area. Animal presence and use of Kimana Swamp Animal presence and use of Ilchalai Swamp Mammal species Frequency (groups) Percentage (%) Frequency (groups) Percentage (%) Chi-square test between swamps Thomson’s gazelle, Gazella thomsoni 150 16 180 16 ( 2 = 2.73, df = 1, p = 0.099)1 Wildebeest, Connochaetes taurinus 125 13 170 15 ( 2 = 6.87, df = 1, p = 0.009) Common zebra, Equus burchelli 120 13 150 13 ( 2 = 3.33, df = 1, p = 0.068) Grants gazella, Gazella granti 90 10 120 11 ( 2 = 4.29, df = 1, p = 0.038) Impala, Aepyceros melaphus 85 9 100 9 ( 2 = 1.22, df = 1, p = 0.27) Common waterbuck, Kobus elliprymnus 75 8 90 8 ( 2 = 1.36, df = 1, p = 0.24) African elephant, Loxodonta africana 60 6 50 4 ( 2 = 0.91, df = 1, p = 0.34) Cokes hartebeest, Alcelaphus buselaphus cokii 60 6 100 9 ( 2 = 10.00, df = 1, p = 0.002) Olive baboon, Papio anubis 50 5 40 4 ( 2 = 1.11, df = 1, p = 0.29) African buffalo, Syncerus caffer 40 4 30 3 ( 2 = 1.43, df = 1, p = 0.23) Common warthog, Phacochoerus aethiopicus 35 4 50 4 ( 2 = 2.65, df = 1, p = 0.10) Common eland, Tragelaphus scriptus 35 4 50 4 ( 2 = 2.65, df = 1, p = 0.10) Common hippopotamus, Hippopotamus amphibious 20 2 10 1 ( 2 = 3.33, df = 1, p = 0.07) Total sightings 945 1140 ( 2 = 18.24, df = 1, p < 0.001) 1There was no significant difference in the between the two swamps if the p-value is less than 5% (alpha of 0.05). The number of sighted groups was similar except in wildebeest, Grants gazelle and hartebeest. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 202 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Table 3. Opinions of local Maasai leaders and opinion leaders on the farming activities in the swamps, consequences for their livelihoods. Issue Opinions of three leaders from Kimana Group Ranch Opinions of three leaders from Mbirikani Group Ranch Opinions of an official of Kimana Community Wildlife Sanctuary Change in number of cultivators in Kimana Swamp -Increases especially during the drought -Increase, about 100 people per year Increased Major events that have shifted land-use -Capitalistic attitudes increasing -Long droughts have caused livestock to die so people turn to agriculture for profit -Livestock numbers keep decreasing so people must supplement with farming -Non-Maasai cultivators are pushing out the Maasai pastoralists -Education -Changing lifestyles -Poverty -Droughts during which people lose many livestock; less of a loss with agriculture -Increasing population cannot support everyone as a pastoralist -Drought in other areas of Kenya -In 1992, it was still a swamp, since then farming has been increasing rapidly -In 1997, due to El Nino it opened the rivers up which drained the swamp -In 2006, heavy rains partially restored the swamp Change in water availability for people - Decreased due to diversions - No change -Decreased due to increased furrow use -No change -Decreased due to diversions Change in swamp availability for livestock Decreased due to fencing and other boundaries -Decreased due to cultivation; livestock must travel to other locations to find water -No change -Decreased Change in water availability for wildlife -Decreased due to cut-off access on the Mbirikani side -Only access is through the Kimana Wildlife Sanctuary -Decreased due to cut-off access on the Mbirikani side -No change, there isn’t a problem with water in the wildlife sanctuary No change due to full access from the sanctuary side Affects of river diversions of rivers draining into swamps for agriculture -Water does not reach as far as it used to, so trees and other vegetation are being reduced -There are no problems with the diversions because the swamp will fill naturally -Wildlife and livestock have to travel to other places to find water; presence of wildlife birds, etc. are reducing -Water doesn’t reach as far which creates conflict -The swamp will become dry because of water loss -People are benefiting from the diversions but it will eventually dry up the swamp -There is a change in vegetation and loss of trees and pasture -Benefits farmers to get more water to their plots Since the rivers upstream are increasingly getting diverted, the water doesn't reach the people downstream, which creates conflict Resources used by the community -Reduced on Mbirikani side because of clearing for cultivation -Non-accessible on sanctuary side -Building materials and crops -Pasture and firewood -Water for drinking and domestic use (which is unsafe because of minerals and pesticides) -Building materials -Water, firewood, and reeds for roofing of house units -Pasture -Before cultivation there was enough water, grazing for livestock and building materials -Now there are no valuable resources (not a concern because the sanctuary provides food, water, cover, and protection for wildlife) Competition for swamp resources -During the night high competition between wildlife and cultivators for water resources because wildlife do not observe land boundaries -During the day, high competition between livestock and cultivators -Human-wildlife conflict for pasture and water -Humans cut down trees to be used for building materials and charcoal which destroys the grazing area -Wildlife destroy cultivators crops -There is competition because everyone must rely on the same area for resources, especially water -Livestock and wildlife eat the destroy crops, and break furrows -Competition for water, firewood, and reeds; burning of the swamp for cultivation angers pastoralists because it depletes pasture -During the dry season there is constant competition for water and vegetation -Conflict of whether to expand cultivation or not -During the dry season the swamp is used to support all livestock, but there is limited access due to cultivation -Causes illegal grazing in the sanctuary Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR 203 Swamp resources that were previously available but are currently in limited supply -Previously, there was enough land for livestock and wildlife to graze on, and for people to collect adequate firewood and building materials -Water has decreased, reeds are limited, pasture is decreasing, and wildlife that was once inhabiting the area has left -Decrease in area that the swamp once covered -Grass for livestock grazing -Lots of pasture, trees, and water were previously available -People are benefiting more, but wildlife have less space -There used to be more hippos and other wildlife -Grazing area for livestock -Water has been contaminated due to pesticide use and pollution Current solutions to help alleviate pressure of use on swamps in Amboseli area -Government officials and group ranch leaders should work together to prevent cultivation, but most of the officials are cultivators which creates conflict of interest -People doing farming and wildlife conservation need to reach an agreement; wildlife conservation is the only viable option -The people don't have any knowledge of other alternatives to agriculture -Pay the farmers and Maasai land owners to not cultivate the land -If agriculture is stopped, the swamp will be able to recover as a result of floods during the rainy season -Limit the number of plots issued to farmers -Technology will be able to help improve irrigation -Give people individual plots so they will maintain it better; -Wildlife stakeholders should provide people with compensation and therefore they would not cultivate -Cement the furrows to reduce water loss and increase efficiency -Easement which pays people to leave their land free of agriculture; currently one household is being paid which is working well -Alternative land leasing strategies other than for cultivation, so that the Maasai to benefit from, but allow environmental and resource conservation leaders attributed this decline to diversion of water from rivers and swamps for farm irrigation purposes. The key informants reported that resources from the swamps were used for construction of homes, cultivation, domestic use, and livestock forage. However they noted a decline of these resources, particularly of pasture in the dry season livestock grazing in the swamps. They also reported that competition for water resources and other resources from the swamps among the farmers, between farmers and wildlife, and between livestock and wildlife is continually increasing. They were concerned that the swamps could be in danger of extinction from the com- bined effects of vegetation clearance, water over utiliza- tion, and general degradation. One official predicted that the swamps could be reduced to wastelands within five years (Table 3). As a solution to this, opinion leaders suggested increased community awareness of the conse- quences of swamp disappearance to community liveli- hood and the environment. However, they recognized that these issues need to be elaborated through negotiated and structured actions that involve all stakeholders. As an alternative option, some opinion leaders suggested prevention of further leasing of Maasai land to non- Maasai tribes for cultivation. In addition, they suggested proper and efficient use of water resources as a way for- ward to conserve the remaining area of the swamps (Ta- ble 3). 4.3. Opinions of Cultivators The majority of cultivators in both Kimana and Ilchalai swamps grew horticultural crops such as tomatoes (Ly- copersicon esculentum), onions (Allium cepa), and other vegetables (Table 4). Most of the cultivators had low level of education and relied wholly on agriculture as their main livelihood. In both swamps, most cultivators were not land owners, but rather leased subdivided land from the local Maasai. A majority of them cultivated less than two acres of land, and for less than a year. A signi- ficant (p < 0.001) majority (over 80%) of the cultivators in both swamps had never paid for the water they used. A majority of the people around Ilchalai Swamp noted that water was declining, while the majority in Kimana noted that either water quantity had remained the same or fluctuated seasonally. Most cultivators in both swamps noted the destruction of crops due to flooding. Additionally, crops in both swa- mps were destroyed by wildlife. The common wildlife crop raiders were elephants, common zebra, and ante- lopes. Most crops raids occurred in the dry season rather than in the wet season. However, more wildlife species raided crops in Kimana Swamp than in Ilchalai Swamp (Table 4). Cultivation in the swamps was mainly motivated by commercial profits rather than subsistence use (Table 4). In both swamps, more people used pesticides and ferti- lizers to optimize output, and had not changed the crops they grew over time. Most farmers preferred cultivation in the swamps because of the constant presence of water, and the relatively fertile land as compared to the sur- rounding landscape (Table 4). It was also cheap to lease swamp land from the Maasai for cultivation. Other bene- fits to cultivation in swamps include the availability of  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 204 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Table 4. Opinions of cultivators in on farming activities within the swamp and level of concern for swamp status. Issue Responses Kimana Swamp Ilchalai Swamp Cultivators’ frequencies (%) χ2, df and p-value Cultivators’ frequencies (%) χ2, df and p-value Tomato 64 (31) 62 (33) Maize (Zea spp.) 54 (26) 49 (26) Beans (Vigna spp.) 40 (19) 20 (10) Onion (Allium spp.) 31 (15) 56 (29) Other (e.g. peas), YamDioscorea Species (Pisum), sp.), yams, kale) 13 (6) 4 (2) Types of crops cultivated Peppers (Capsicum spp.) 7 (3) χ2 =72.081; df = 5; p < 0.001 - χ2 = 65.47; df = 4; p < 0.001 Primary school 70 (72) 60 (75) Secondary school 16 (17) 11 (14) Level of education completed No formal education 11 (11) χ2 = 66.206; df = 2; p < 0.0019 (11) χ2 = 106.80; df = 3; p < 0.001 Farming 89 (90) 75 (92) Agro-pastoralism 6 (6) 3 (4) Livelihood sources Farming with other 4 (4) χ2 = 142.606; df = 2; p < 0.0013 (4) χ2 = 128.00; df = 2; p < 0.001 Rent (lease) 81 (82) 73 (90) Partnership with Maasai 10 (10) 1 (1) Land ownership Own the land 8 (8) χ2 = 104.788; df = 2; p < 0.0017 (9) χ2 = 118.22; df = 2; p < 0.001 No 42 (59) 49 (60) Farm expansion or new farms Yes 29 (41) χ2 = 2.380; df = 1; p = 0.12332 (40) χ2 = 3.82; df = 1; p = 0.11 No 90 (95) - No (relies on rain) 5 (5) 66 (81) Payment for water Yes 0 (0) χ2 = 76.053; df = 1; p < 0.00115 (19) χ2 = 32.11; df = 1; p < 0.001 Same 39 (49) 6 (7) Seasonal fluctuation 23 (29) 23 (29) Decrease 16 (20) 46 (57) Water availability Increase 2 (2) χ2 = 35.500; df = 3; p < 0.001 6 (7) χ2 = 53.17; df = 3; p < 0.001 Yes 86 (90) 70 (86) Flood damage No 10 (10) χ2 = 60.167; df = 1; p < 0.00111 (14) χ2 = 58.6; df = 1; p < 0.001 Profit 49 (67) 75 (66) Subsistence 16 (22) 30 (26) Reasons for farming Profit/subsistence 8 (11) χ2 =38.822; df = 2; p < 0.0019 (8) χ2 = 59.84; df = 2; p < 0.001 Yes 55 (57) 76 (92) Fertilizer use No 42 (43) χ2 = 64.281; df = 4; p = 0.1877 (8) χ2 = 57.36; df = 1; p < 0.001 Yes 56 (58) 71 (86) Pesticide use No 40 (42) χ2 = 2.667; df = 1; p = 0.10212 (14) χ2 = 41.94; df = 1; p < 0.001 No 50 (54) 35 (43) Change of crops cultivated over Yes 42 (46) χ2 = 0.696; df = 1; p = 0.40446 (57) χ2 = 1.49; df = 1; p = 0.22 Yes 82 (83) 79 (98) Crop damage by wildlife No 17 (17) χ2 = 42.677; df = 1; p < 0.0012 (2) χ2 = 73.2; df = 1; p < 0.001 Elephants 22 (58) 48 (57) Zebra 5 (14) 15 (18) Buffalo 4 (10) - Antelopes/ Wildebeest 4 (10) 20 (24) Most destructive animals to crops Hippopotamus 3 (8) χ2 = 34.368; df = 4; p < 0.001 1 (1) χ2 = 55.52; df = 3; p < 0.001 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 205 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Dry Season 96 (100) 66 (93) Season when most wildlife damage occurs Rainy Season 0 (0) Chi-square not necessary 5 (7) χ2 = 52.41; df = 1; p < 0.001 Water availability 53 (53) 69 (55) Farm year round 13 (13) 5 (4) Other (e.g. pastoralism, word of mouth) 12 (12) 9 (7) Homeland too dry 10 (10) - Fertile Soil 9 (9) 43 (34) Reasons for cultivation in the swamp For a better life/money 3 (3) χ2 = 98.720; df = 5; p < 0.001 - χ2 = 51.54; df = 3; p < 0.001 Drinking water 55 (61) 60 (74) Building material 46 (51) 49 (61) Domestic use (e.g. cooking, washing) 35 (39) 61 (75) Farming (e.g. irrigation) 34 (38) 70 (86) None 6 (7) 3 (4) Resources in the swamp used by cultivators* Livestock (e.g. grazing, watering) 3 (3) χ2 = 74.642; df = 5; p < 0.001 45 (56) χ2 = 82.2; df = 5; p < 0.001 Move elsewhere to cultivate 25 (25) 53 (65) Won’t dry up 18 (18) - Business 15 (15) 10 (13) Go back home 13 (13) 5 (6) No alternative 10 (10) 9 (11) Other (e.g. plant trees, wait for rain, look to God) 6 (6) - Another career/trade 5 (5) - No idea 4 (4) - Alternative livelihoods if Kimana Swamp was to dry up Pastorialism 4 (4) χ2 = 38.240; df = 8; p < 0.001 4 (5) χ2 = 106.10; df = 4; p < 0.001 Yes 67 (76) 56 (69) Concerned about swamp conversion No 21 (24) χ2 = 38.291; df = 1; p < 0.00125 (31) χ2 = 57.2; df = 1; p < 0.001 No 49 (33) - Only Agriculture 39 (26) 22 (27) Wildlife conservation and tourism 29 (19) 20 (25) Yes, but do not know options 15 (10) 1 (1) Depends on owner 13 (9) - Drinking water forlivestock 4 (3) - Preferred multi-purpose land use in swamps Agro-pastoralism - χ2 = 59.309; df = 5; p < 0.001 38 (47) χ2 = 34.1; df = 3; p < 0.001 *Frequencies in this category may not necessarily add to 100 because interviewees may have given more than one response. resources such as water for drinking, domestic use, and watering livestock, as well as building materials (poles, sticks and grass). More people in Ilchalai used water for watering livestock than in Kimana Swamp (Table 4). A significantly (p < 0.001) majority of the people (over 70%) in both Kimana and Ilchalai were concerned over the diminishing size of the swamps. A majority of culti- vators in Kimana did not favor multiple uses of swamps, but instead preferred either agriculture or other resource use. In Ilchalai Swamp, most cultivators favored agri- culture, followed by wildlife conservation (Table 4) as the best use of the swamps. There were differences in opinions over what course of action to take should the swamp in their area completely dry up. Most of the cul- tivators in Ilchalai suggested that they would move else- where to continue cultivation. However, a number of cul- tivators in Kimana did not believe that complete drying of the swamp could ever occur. Other alternative course Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 206 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya of actions mentioned by cultivators in both swamps in- cluded engaging in business, in returning to their native homes, or that they could not have any other livelihood option. 4.4. Opinions of Local Maasai Landowners Nearly all the local landowners around the two swamps belonged to the Maasai tribe. Household sizes for these people ranged from 6 - 10 individuals (Table 5). The majority practiced agro-pastoralism and mostly depend- ed on the swamps for livelihood and provision of basic good for survival. Nearly all the Maasai households re- lied on swamps for drinking and domestic water use as well as for poles, sticks, and grass from the swamps to build their homes. Nearly all local Maasai also noted an increase in the number of people depending on the swa- mps for livelihoods, thereby contributing to a reduction in swamp size (Table 5). They singled out wildlife da- mages as the main challenge to agriculture expansion in the swamps. Nearly all the Maasai around both swamps noted a de- cline in the frequency of wildlife using the swamps, but few attributed this to expansion of agriculture (Table 5). Around Kimana Swamp, they noted an increase in the frequency of livestock of the swamps, while around Il- chalai Swamp the majority of the Maasai noted a decline in livestock access to the swamps because of agriculture. Communities surrounding both swamps noted that access to building materials has declined but access to water for domestic purposes has remained the same. They also no- ted that there was nothing the government, group ranch leadership or themselves as individuals would do to solve perceived threats to the swamps. However, they sug- gested that the best use of the swamps and its resources was first cultivation, followed by pastoralism, and other multiple uses. Wildlife conservation was least of the pre- ferred swamp use of swamps by local Maasai landow- ners (Table 5). Local Maasai in both swamps suggested various stra- tegies for alternative livelihoods should the swamps dry up. Many people near Kimana Swamp reported that they would either turn to God (prayer) or move elsewhere to pursue cultivation. Others in that area said they would turn exclusively to pastoralism or a paid job. Others ad- mitted that they have no alternative livelihoods in the event that the swamp dries up completely. The commu- nity around Ilchalai Swamp mostly reported that they would move elsewhere or turn exclusively to pastoralism. Further, a large number of people in Ilchalai swamp re- ported that they had not yet considered an alternative livelihood strategy. A relatively smaller number reported that they would turn to God (prayer) for help (Table 5). 5. Discussion The loss and decline (quantity, availability and access) of swamps and water resources in swamps as a result of increasing and unsustainable exploitation is clearly evi- dent. This is a major concern in the Amboseli ecosystem because mismanagement and misuse of water sources will directly reduce local livelihoods and quality of life. Water availability and wildlife damages will undoubt- edly be the limiting factors to further expansion of agri- culture in the area. Conversion of swamp land for culti- vation is steadily increasing. The result is an increase in the negative impacts of agriculture such as degradation of soils and water sources from pollutants (fertilizers and pesticides). The migration of people to this area to prac- tice agriculture has resulted in over-utilization of plant resources for cooking, fencing, building shelters and other human uses. The demand for such materials has further threatened swamp habitats for biodiversity. The swamps in the Amboseli area, Kenya, just as many countries in the world, is undergoing water stress [2,3,5]. Demand for water is going to increase, together with associated conflicts and concerns on availability and usage. All wetlands are a critical life supporting system providing goods and services to the wildlife and people within, as well as those in adjacent ecosystems [15]. The swamps provide surrounding communities with poles, reeds, and grass for building their houses. They also sup- ply water for irrigation, cooking, drinking, and bathing. They are the only source of water and forage for live- stock and wildlife especially during the dry season. How- ever, with increasing agriculture all of these natural re- sources are steadily decreasing. This is likely to increase conflicts as herder-herder, farmer-farmer, farmer-herder and farmer-wildlife conflicts over shortages and inade- quate distribution of water and other swamp resources [16]. With Kenya’s limited rainfall, agriculture in arid lands such as in the Amboseli ecosystem can only be practiced in the few wetlands and in the lower slopes of Mt. Kili- manjaro [17]. Readily accessible water, fertile soils, and Maasai landowners willing to lease, make these swamps ideal for commercially motivated agriculture. A majority of the local Maasai had the impression that the best use of the land was agriculture. Agriculture is profitable, and it provides a substantial amount of food, direct household income, and jobs for the community over wildlife and pastoralism [13,18,]. However, unaware of long-term consequences, most people in the area support agricul- ture over pastoralism and wildlife conservation because of the immediate and direct benefits they receive [19]. They may not fully understand the permanent effects of Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR 207 Table 5. Opinions of local Maasai land owners in response to the farming activities in the swamps, consequences for their livelihoods and the way forward. Kimana Swamp Ilchalai Swamp Issues Responses Cultivators’ frequencies (%) χ2, df and p-value Cultivators’ frequencies (%) χ2, df and p-value Female 60 (73) 66 (73) Gender Male 22 (27) χ² = 17.61; df = 1; p < 0.00124 (27) χ² = 19.60; df = 1; p < 0.001 1 - 5 20 (24) 36 (41) 6 - 10 40 (49) 43 (48) 11 - 15 15 (18) 3 (3) 16 - 20 5 (6) 5 (6) Family Size More than 20 2 (3) χ² = 55.44; df = 4; p < 0.001 2 (2) χ² = 89.82; df = 4; p < 0.001 Maasai 79 (96) 89 (99) Tribe Other Kenyan Tribes 3 (4) χ² = 70.44; df = 1; p < 0.0011 (1) χ² = 86.04; df = 1; p < 0.001 1 month - 7 years 44 (60) 69 (78) 8 - 15 years 18 (25) 7 (8) 16 - 22 years 3 (6) 5 (6) 23 - 29 years 1 (1) 2 (2) Over 29 years - 2 (2) Time of residence in the area near swamps Unknown - χ² = 71.58; df = 3; p < 0.001 4 (4) χ² = 211.29; df = 4; p < 0.001 Agro-pastoralism 65 (79) 60 (67) Pastoralism 11 (14) 28 (31) Agriculture 6 (7) 1 (1) Livelihood of local Maasai land owners Other (job/business) - χ² = 78.32; df = 2; p < 0.001 1 (1) χ² = 104.93; df = 3; p < 0.001 1 - 2 1 (1) 1 (1) 3 - 4 3 (4) 9 (10) 5 - 6 15 (18) 17 (19) 7 - 8 18 (22) 19 (21) Degree of reliance on swamp for resources (1 low and 10 high) 9 - 10 45 (55) χ² = 75.56; df = 4; p < 0.001 44 (49) χ² = 58.22; df = 4; p < 0.001 Yes 78 (95) 75 (83) If swamp plant resources were used to build homes No 4 (5) χ² = 66.78; df = 1; p < 0.00115 (17) χ² = 40.00; df = 1; p < 0.001 Sticks 66 (73) 18 (20) Reeds 49 (60) 55 (60) Grass 32 (39) 45 (49) Plant Resources used to build homesteads from swamps* Other 8 (10) χ² = 44.26; df = 3; p < 0.001 2 (2) χ² = 59.27; df = 3; p < 0.001 Stream/River/Furrow 58 (72) 88 (98) Source of drinking water Pipeline 23 (28) χ² = 15.23; df = 1; p < 0.0012 (2) χ² = 82.18; df = 1; p < 0.001 Increased 80 (99) 85 (94) Same 1 (1) 4 (5) Changes in population size dependence on the swamp Decreased 0 (0) χ² = 77.049; df = 1; p < 0.001 1 (1) χ² = 151.40; df = 2; p < 0.001 Increased 1 (1) 10 (11) Same 20 (25) 22 (24) Observed changes in swamp size Decreased 60 (74) χ² = 45.70; df = 2; p < 0.001 58 (64) χ² = 41.60; df = 2; p < 0.001 Yes 50 (61) 51 (57) If there are problems affecting swamp agriculture activities No 32 (39) χ² = 13.95; df = 1; p = 0.04739 (43) χ² = 1.60; df = 1; p = 0.206  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 208 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Wildlife Damages - 40 (43) None 53 (75) 30 (33) Increased cultivation 13 (18) 30 (33) Decreased rainfall 3 (4) 25 (28) Factors threatening the swamp’s existence* Diversion of Rivers 2 (3) χ² = 97.50; df = 3; p < 0.001 5 (6) χ² = 25.08; df = 4; p < 0.001 Yes 77 (94) 60 (67) If there are changes in wild- life use of the swamp No 5 (6) χ² = 63.20; df = 1; p < 0.00130 (33) χ² = 10.00; df = 1; p = 0.002 Increased 48 (67) 25 (28) Same 16 (22) 10 (11) Changes in livestock accessing dry-season grazing in swamps Decreased 8 (11) χ² = 37.30; df = 2; p < 0.00155 (61) χ² = 35.00; df = 2; p < 0.001 Increased 1 (1) 22 (24) Same 53 (65) 44 (49) Changes in accessing clean drinking water from the swamps Decreased 28 (34) χ² = 49.48; df = 2; p < 0.001 24 (27) χ² = 9.87; df = 2; p = 0.007 Increased 5 (6) 1 (1) Same 15 (18) 34 (38) Changes in accessing home building resources from swamps Decreased 62 (76) χ² = 67.78; df = 2; p < 0.001 55 (61) χ² = 49.40; df = 2; p < 0.001 Community action 10 (12) 11 (12) Health improvements 1 (1) 3 (3) Pipeline/well 11 (14) 13 (15) Fence 2 (2) 3 (3) What can you do to help as an individual Nothing 58 (71) χ² = 136.90; df = 4; p < 0.001 60 (67) χ² = 127.11; df = 4; p < 0.001 Compensation 2 (2) 5 (6) Regulation of water 25 (30) 22 (25) Nothing 62 (76) 57 (63) Education 9 (11) 2 (2) Health facilities 3 (4) 2 (2) What local group ranch leadership can do to help conserve swamps* Fence 2 (2) χ² = 163.039; df = 5; p < 0.001 2 (2) χ² = 161.33; df = 5; p < 0.001 Education 15 (18) 10 (11) Defense from wildlife 10 (12) 14 (!6) Nothing 52 (63) 44 (49) Health center 2 (2) 8 (9) Compensation 10 (11) 2 (2) What the government can do to help conserve swamps* Wells/Water control 5 (5) χ² = 107.57; df = 5; p < 0.001 12 (13) χ² = 72.93; df = 5; p < 0.001 Cultivation 45 (55) 42 (46) Pastoralism 41 (50) 36 (39) Mixed Use 38 (46) 31 (34) Wildlife Conservation 8 (10) 5 (5) Opinion on best use of swamps and their resources* Building Resources 10 (12) χ² = 45.11; df = 4; p < 0.001 2 (2) χ² = 76.21; df = 4; p < 0.001 Does not know 9 (11) 15 (17) Move elsewhere 23 (28) 34 (38) Exclusive pastoralism 10 (12) 15 (17) Use pipeline/dig wells 3 (4) 11 (12) God (Prayers) 37 (45) 10 (11) Turn to job/business 10 (12) 3 (3) Alternative livelihood if the swamp dries up* Hope for Rain 5 (6) χ² = 62.70; df = 6; p < 0.001 2 (2) χ² = 53.11; df = 6; p < 0.001 *Frequencies in these categories may not necessarily add to 100 because interviewees may have given more than one response. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR 209 altering the ecology of the landscape nor contemplate an alternative livelihood in the event that the swamps dry up. Farmers influence land-use changes in arid areas, where swamps and riverine areas are seen as oasis of wealth. Unless wildlife-based crop raiding and livestock depre- dation costs are reduced, and a system of compensation from wildlife damage is implemented, the prevailing ne- gative local attitudes towards wildlife will undermine all conservation efforts [20]. Without compensation and economic benefits from wildlife conservation [9,12,15] alternative and economically lucrative land uses such agriculture will dominate and expand, even in unsustain- able dry lands like the Amboseli area. In Amboseli the shift in land use from pastoralism even in critical habitats has put pressure on the scarce water sources, thus in- creasing competition and potential people-people, peo- ple-wildlife, people-livestock, and livestock-wildlife con- flicts over resources [13,19]. Furthermore, this displaces and separates people from critical resources such as swamps. This will increase poverty and environmental degradation given that the majority of these people have no significant education, and rely on these resources for basic livelihood needs [10,13]. Destruction of unique riparian vegetation leads to de- gradation and displacement of dependent wildlife species such as the common Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus am- phibious), waterbuck, elephants etc. Further, as most ran- gelands become overgrazed due to lack of access to wet- lands during the dry season, which relieve excessive gra- zing pressure on the rangeland, pastoralism is likely to decline. There is a high demand for land in the swamp area, so agriculture is continually expanding. Despite the presently good fertile soils, it is only a matter of time before the soil becomes sodic, unable to support vegeta- tion and crops. This presents a wider ecosystem problem because the cultivators are likely to move in other wet- lands and continue to put pressure on the remaining swa- mps in the area. It is impossible to completely eradicate agriculture from the swamps because it provides subsistence and commercial benefits. However, a balanced use with pas- toralism and wildlife should be promoted urgently. The traditional Maasai practice of pastoralism is declining due to draughts, lack of a competitive market for beef, and changing land tenure. Many of these people have turned to share cropping or cultivation of horticulture produce, which provide significant profits, as an alterna- tive livelihood. Therefore, mitigation measures should contain and manage, rather than eliminate, the negative impacts of agriculture. One way to do this is to require all water pathways to farms to be cemented. This mini- mizes water loss and percolation into the soil. Water flow needs to be regulated through time and quantity of use in order to maintain sufficient access for people, livestock, and wildlife downstream. Additionally, farm- ers should be required to rotate their crops throughout different seasons to maintain soil fertility and enhance land productivity. This would also reduce dependence on fertilizer supplements that are polluting. A final alterna- tive that should be considered is organic farming. There is abundant manure from livestock available at nearby Maasai homesteads, which can be used to support soil fertility rather than depend on commercial fertilizers. As the demand for agriculture intensifies, it is essential to clearly elaborate implications of these changes to community livelihood and to wildlife conservation [1,6, 20]. If measures are not taken to control agriculture ex- pansion and water over-use in swamps, the livelihood of the Maasai people in the area will be adversely affected. In addition, the dispersal area will become less habitable to wildlife. It needs to be clear to the Maasai that quick benefits from immigrants coming to farm in the wetlands does not necessarily positively benefit the future and longevity of the swamps. It will take the community self- awareness to address depletion of these resources which provide a lifeline for the prosperity of current and future generations. If water resource access rights, equitable and sustainable use is not planned, promoted, and en- forced within a practical rural resource conservation and use policy framework, then negative consequences for the environment and human livelihoods will certainly follow. 6. Conclusions The bottom line for the the Maasai survival in the area is using anything found in their landscape for survival and livelihoods. Such short term survival priorities dominate over long term issues of environmental conservation or wise resource use. If families cannot make a living and meet basic needs, they will use land and its resources for survival, even if unsustainable. Nevertheless reckless and thoughtless use of resource for short-term survival will lead to the long resource and environmental degradation will sure make livelihood and quality of life difficulty for this community. It is not very easy to convince those converting the wetlands for agriculture that land and wa- ter resources can be exhausted when misused. Many are in denial about this, and even more are unsure of how to take action, even when the consequences are apparent to them. In order to reverse this challenge, we have to mount aggressive awareness and alternative livelihoods, and try to clearly link peoples’ survival with natural re- source conservation and explain it in a manner that  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in 210 Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya stakeholders and users will understand and appreciate to spur the local community itself to self restrain and wise use of natural resources, and other appropriate actions. This study looks at a critical resource in changing dryland. With the entire world looking at the effects of climate change and how local communities are affected or copying with it, it is clear from this work that poverty, population increase and lack of economic opportunities drive people to over-exploit critical resources to their future detriment [1,21]. Yet the cycle of poverty and im- poverishment within the context of harsh environmental conditions, droughts and global climate change exacer- bate the situation leading to lack of food security and depressed livelihood. This work is a good case study to the dependence of the Maasai on wetlands, but how this dependence is being compromised by short term gains from agriculture and how this reduces productivity of their land and resilience of pastrolism which relied on these wetlands for pasture in prolonged dry seasons and drought. Mitigation strategies that include education the Maasai to conserve critical habitats for posterity as well as helping them understand, cope with and adapt to cli- matic changes is critical so as to contain negative land use changes to their way of life and livelihoods. 7. Acknowledgements We would like to thank SFS summer 2006 students for participating in this research: Margaret Donahue, Becky Fried, Jamie Gibbs, Alyson Howe, Emily McIntire, Mi- chelle Mercier, Whitney Patrick, Beth Sturgeon, Elliot Thomsen, Katie Sue Zellner, Julie Bordua, Britne Gose, Allison Habekost, Georgia Kirkpatrick, Shannon Pet- ticrew, Erica Pfleiderer, Len Rodman and Katie Rohan. We also thank field assistants: Martin Pullei, Simon Sayioki, John Mpaa and Wilson Musikeri. Finally, we thank Kimana Kuku, and Mbirikani group ranches for allowing this work, and SFS for financial and logistical support. We also thank anonymous reviewers who con- tributed to improvement of earlier manuscripts. REFERENCES [1] J. Worden, R. Reid and H. Gichohi, “Land-Use Impacts on Large Wildlife and Livestock in the Swamps of the Greater Amboseli Ecosystem, Kajiado District, Kenya,” The Land Use Change, Impacts and Dynamics (LUCID) Project. Working Paper Series Number 27, International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi, 2003. http://www. lucideastafrica.org [2] P. Rogers, “Facing Freshwater Crisis,” Scientific American, 2008. www.SciAm.com [3] Earth Watch Institute, “Emerging Water Shortages,” World-Watch News Release, 1999. http://www.earthwatch.org/node/1654 [4] UNESCO (United Nations Environmental Scientific and Cultural Organization) “Water Availability and Deficits,” 2000. httpt:/www.unesco.org/science/waterday2000/availability _ and_deficts.html [5] S. Vaknin, “The Emerging Water Wars,” Published by United Press International (UPI), 2002. httpt://www.samvak.tripod.com/pp146.html [6] D. J. Campbell, H. Gichohi, A. Mwangi and L. Chege, “Land Use Conflict in Kajiado District, Kenya,” Land Use Policy, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2000, pp. 337-348. doi:10.1016/S0264-8377(00)00038-7 [7] J. Kioko, P. Muruthi, P. Omondi and P. Chiyo, “The Per- formance of Electric Fences as Elephant Barriers in Am- boseli, Kenya,” South African journal of Wildlife Research Vol. 38, No. 1, 2008, pp. 52-53. doi:10.3957/0379-4369-38.1.52 [8] E. Barrow, P. Lembuya, P. Ntiati, and D. Sumba, “Knowl- edge, Attitudes and Practices Concerning Community Con- servation in Kuku and Rombo Group Ranches around Tsavo West National Park,” Community Conservation Discussion Paper No. 12, African Wildlife Foundation, Nairobi, 1993. [9] N. W. Sitati, M. J. Walpole and N. Leader-Williams, “Fac- tors Affecting Susceptibility of Farms to Crop Raiding by African Elephants: Using a Predictive Model to Mitigate Conflict,” Journal of Applied Ecology, Vol. 42, No. 6, 2005, pp. 1175-1182. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2005.01091.x [10] M. M. Okello and J. W. Kiringe, “Threats to Biodiversity and the Implications in Protected and Adjacent Dispersal Areas of Kenya,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2005, pp. 55-69. doi:10.1080/09669580408667224 [11] E. Fratkin, “Pastoral Land Tenure in Kenya: Maasai, Sam- buru, Boran, and Rendille Experiences 1950-1990,” No- madic Peoples, Vol. 34, No. 35, 1994, pp. 55-68. [12] D. Western, “Amboseli national park. Enlisting Landown- ers to Conserve Migratory Wildlife,” Ambio, Vol. 11, No. 5, 1982, pp. 302-308. [13] M. M. Okello, “Land Use Changes and Human-Wildlife Conflicts in the Amboseli Area, Kenya,” Human Dimen- sions of Wildlife, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2005, pp. 19-28. doi:10.1080/10871200590904851 [14] J. H. Zar, “Biostatistical Analysis” 4th Edition, Prentice- Hall, Upper Saddle River, 1999. [15] D. Western, “Water Availability and Its Influence on the Structure and Dynamics of a Savanna Large Mammal Community,” East Africa Wildlife Journal, Vol. 13, 1975, pp. 265-286. [16] T. Burkey, “Faunal Collapse in East African Game Re- serves Revisited,” Biological Conservation, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1994, pp. 107-110. [17] J. Kioko, J. M. Okello and P. Muruthi, “Elephant Num- Bers and Distribution in the Tsavo-Amboseli Ecosystem, South-Western Kenya,” Pachyderm, Vol. 40, 2006, pp. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  A Field Study in the Status and Threats of Cultivation in Kimana and Ilchalai Swamps in Amboseli Dispersal Area, Kenya Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR 211 61-68. [18] R. Mace, “Transition between Cultivation and Pastoralism in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Current Anthropology, Vol. 34, No. 4, 1993, pp. 363-382. doi:10.1086/204183 [19] M. M. Okello, “An Assessment of the Large Mammal Component of the Proposed Wildlife Sanctuary Site in Maasai Kuku Group Ranch near Amboseli, Kenya,” South African Journal of Wildlife Research, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2005, pp. 63-76. [20] J. W. Kiringe, M. M. Okello and S. W. Ekajul, “Managers’ Perceptions of Threats to the Protected Areas of Kenya: Prioritization for Effective Management,” Oryx, Vol. 41, No. 3, 2007, pp. 1-8. doi:10.1017/S0030605307000218 [21] J. W. Kiringe and M. M. Okello, “Use and Availability of Tree and Shrub Resources on Maasai Communal Range- lands near Amboseli, Kenya,” African Journal of Range and Forage Science, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2005, pp. 37-46.

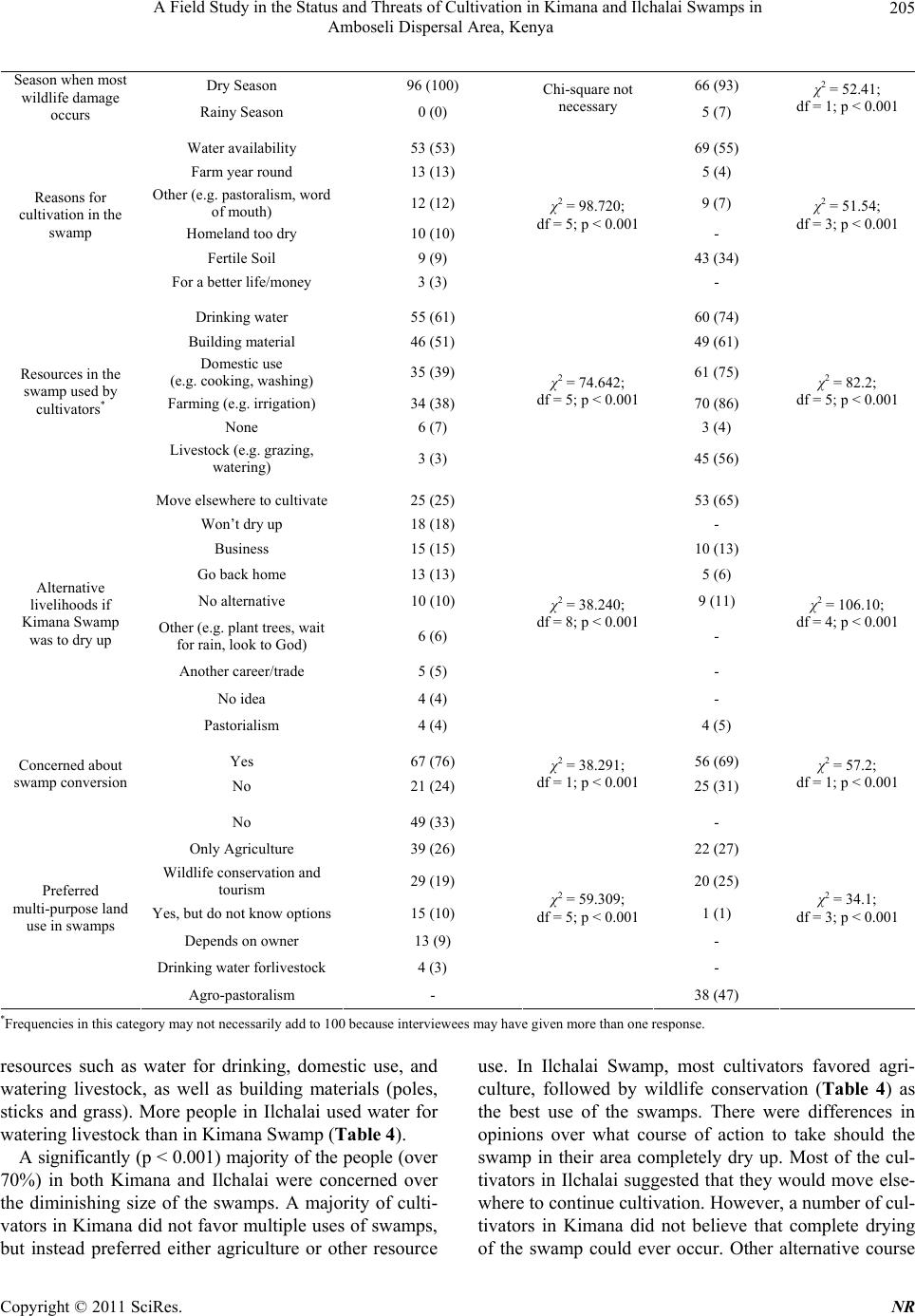

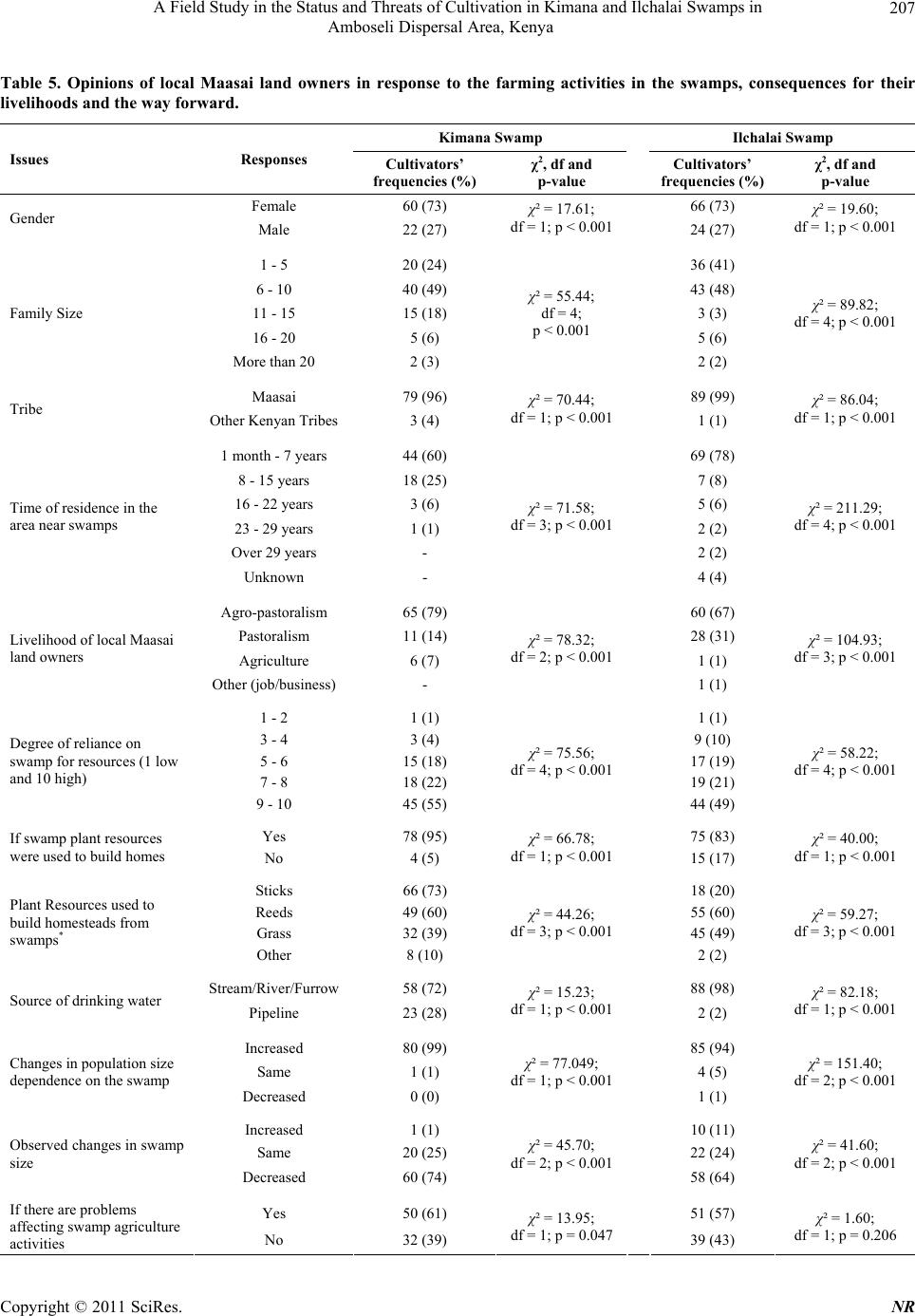

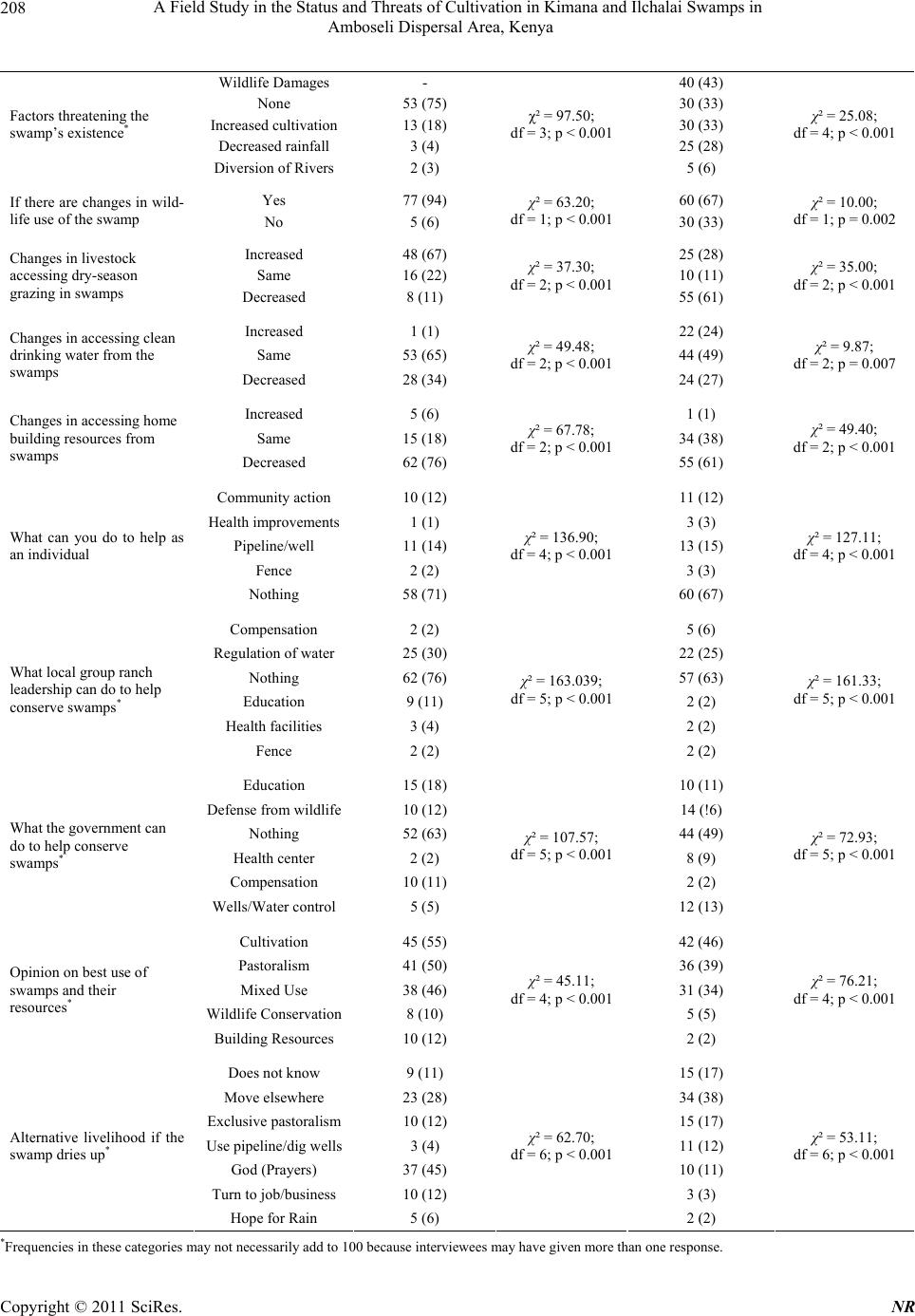

|