Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

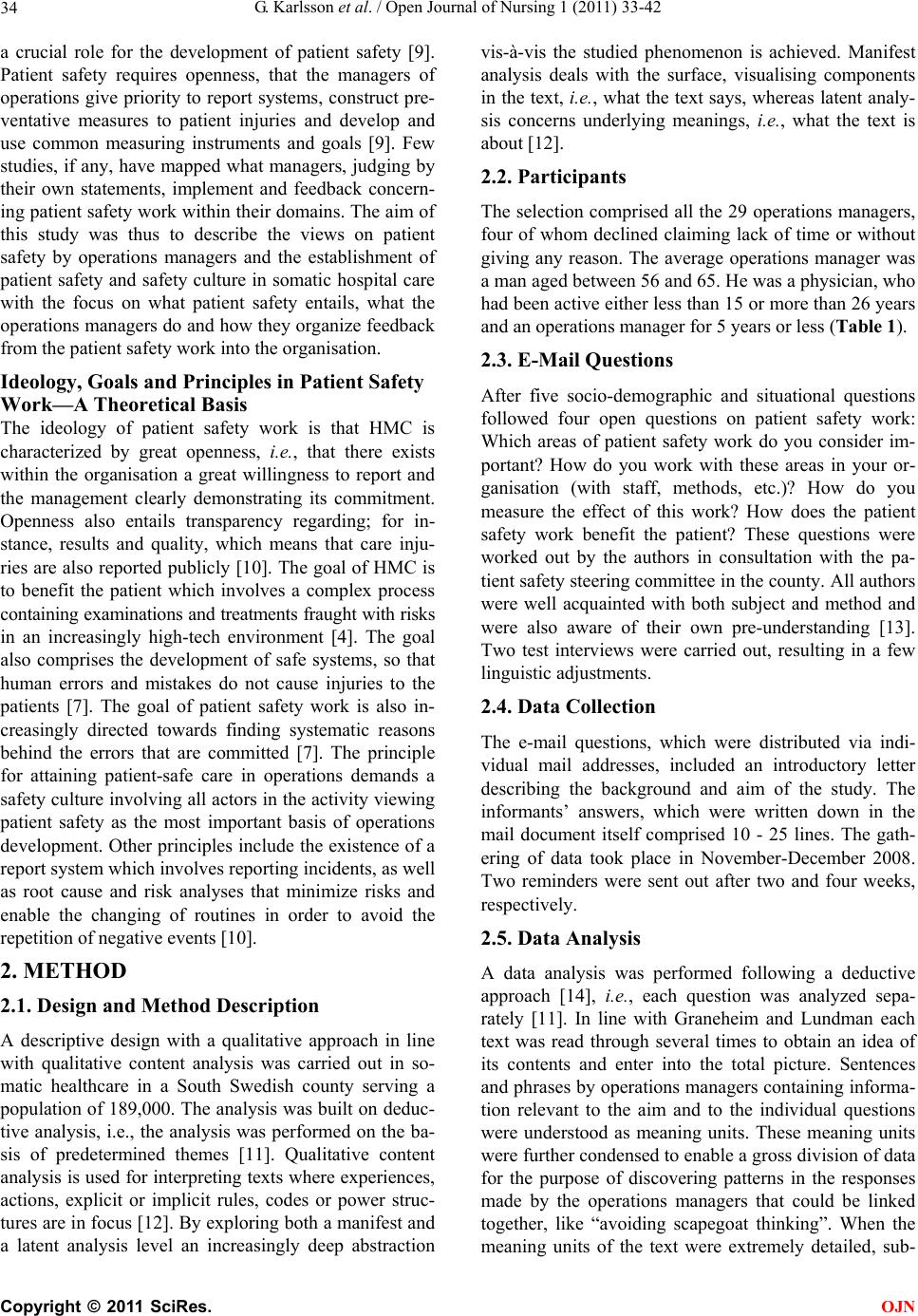

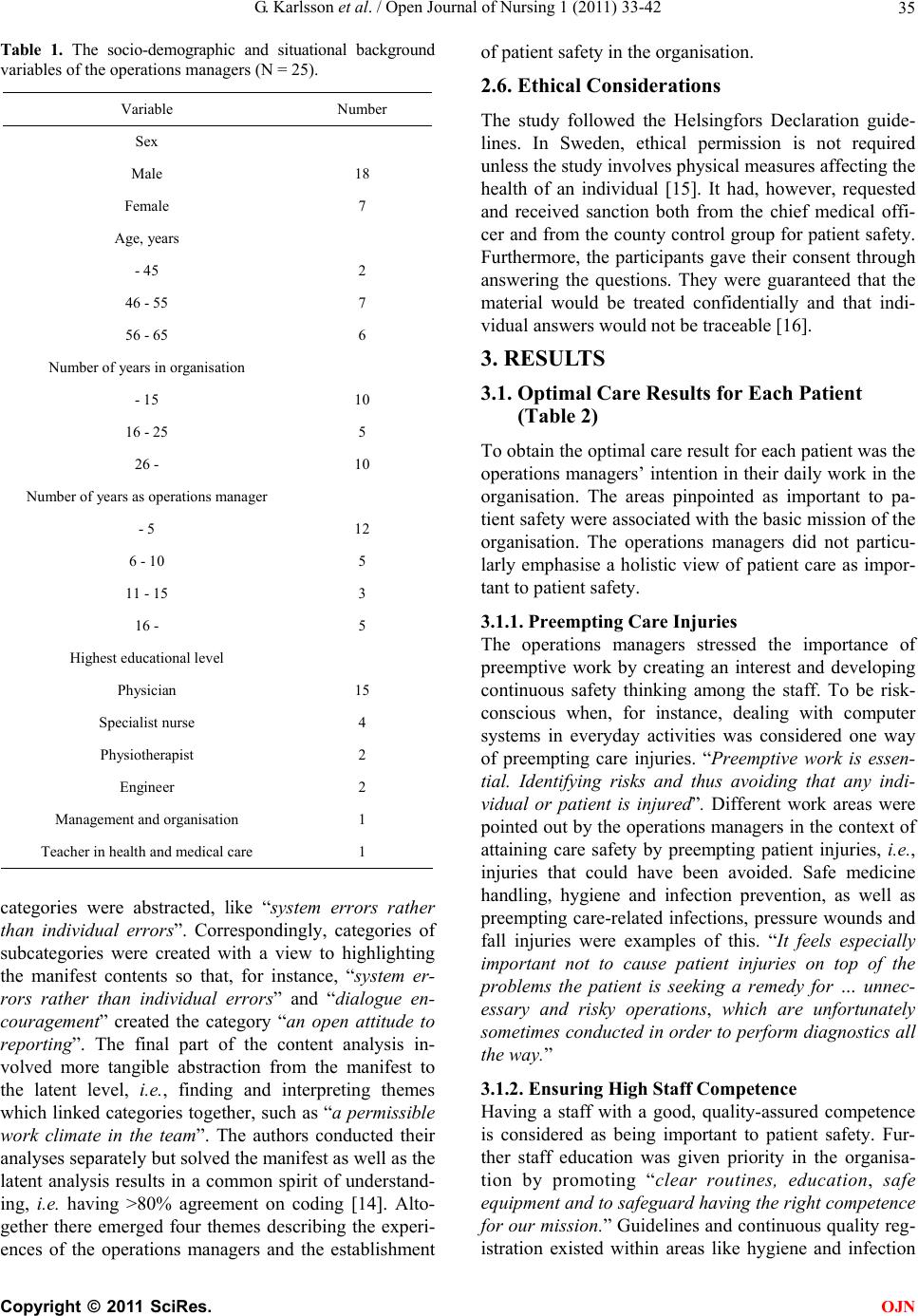

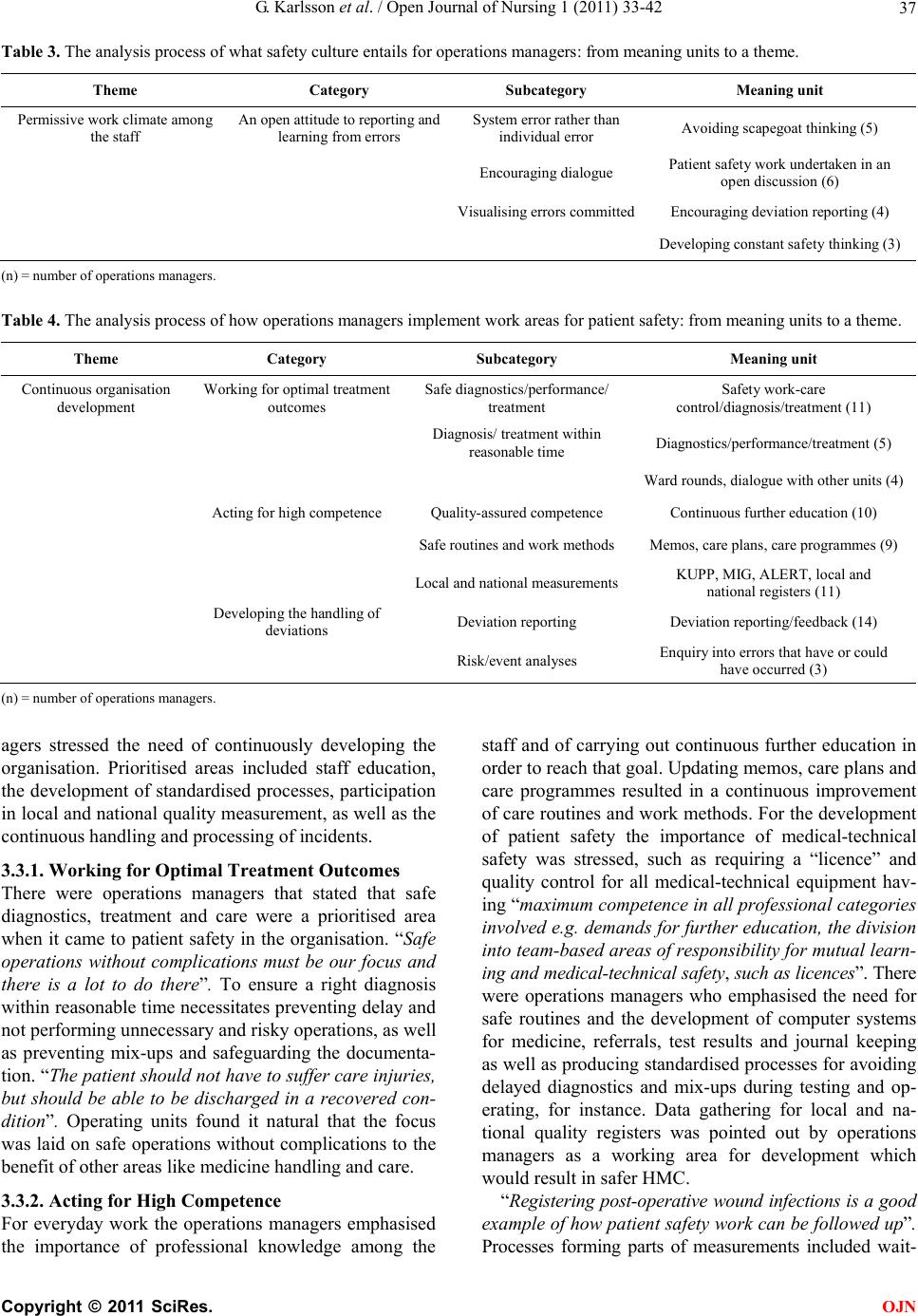

Open Journal of Nursing, 2011, 1, 33-42 OJN doi:10.4236/ojn.2011.13005 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJN/). Published Online December 2011 in SciR es. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJN Views on patient safety by operations managers in somatic hospital care: a qualitative analysis Gunilla Karlsson1, Karl Hedman2, Bengt Fridlund3* 1Department of Intensive Care, Central Hospital, Växjö and School of Health and Caring Sciences, Linnaeus University, Campus Växjö, Växjö, Sweden; 2School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping and Department of Sociology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden; 3School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping and School of Health and Caring Sciences, Linnaeus University, Cam- pus Växjö, Växjö, Sweden. Email: *bengt.fridlund@hhj.hj.se Received 23 July 2011; revised 2 November 2011; accepted 22 November 2011. ABSTRACT Healthcare outcome is to achieve optimal health for each patient. It is a well-known phenomenon that patients suffer from care injuries. Operations man- agers have difficulties in seeing that the relationship between safety culture, values and attitudes affects the medical care to the detriment of the patient. The aim was to describe the views on patient safety by operations managers and the establishment of patient safety and safety culture in somatic hospital care. Four open questions were answered by 29 operations managers in somatic hospital care. Data analysis was carried out by deductive qualitative content analysis. Operations managers found production to be the most important goal, and patient safety was linked to this basic mission. Safety work meant to achieve op- timal health outcomes for each patient in a continu- ous development of operations. This was accom- plished by pursuing a high level of competence among employees, having a functioning report sys- tem and preventing medical errors. Safety culture was mentioned to a smaller extent. The primary tar- get of patient safety work by the operations managers was improving care quality which resulted in fewer complications and shorter care time. A change in emphasis to primary safety work is necessary. To ac- complish this increased knowledge of communication, teamwork and clinical decision making are required. Keywords: Evaluation; Healthcare Improvement; Pro- fessional Healthcare; Patient Safety; Qualitative Content Analysis; Safety Culture 1. INTRODUCTION It is a well-known phenomenon that patients are injured during contacts with health and medical care (HMC). Further, it is estimated that more than 50% erroneous assessments and treatments could have been avoided [1, 2]. In spite of this knowledge the development of patient safety has been slow [3,4] especially due to the values, attitudes, norms and behaviour of the healthcare staff that control where the focus is in regard to patient safety issues [1]. Since the 1990s international studies have demon- strated that upwards of 10% of patients in HMC have been injured or have died as a result of erroneous heal- thcare assessments or treatment [2,5]. A corresponding Swedish national study of 2000 medical journals showed that nine percent of the patients suffered health care inju- ries, each injury causing on average an additional six days in the hospital. In three percent the care injury was associated with the death of the patient. Deficiencies in patient safety and healthcare injuries also resulted in prolonged care time, re-admission, wound infections and medication side effects in close to every tenth hospitali- zation [6]. Patient safety culture is thus considered the most important factor to improve patient safety [1]. This upgrading requires cooperation between different pro- fessions and medical specialities, as well as high risk awareness with the aim to improve both the content and results of HMC [7]. One prerequisite for attaining a pos itive safety culture consequently requires the support and resources of the hospital management and operations managers [8]. Past research has shown that despite th e knowledge about the consequences for both patients and the HMC, its man- agers do not give priority to patient safety. They have difficulty to appreciate the effect that the values and at- titudes of patient safety culture may have on HMC to the detriment of the patient [4]. The managers of today and their attitudes to and understanding of safety culture play  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 34 a crucial role for the development of patient safety [9]. Patient safety requires openness, that the managers of operations give priority to report systems, construct pre- ventative measures to patient injuries and develop and use common measuring instruments and goals [9]. Few studies, if any, have mapped what managers, judging by their own statements, implement and feedback concern- ing patient safety work within their domains. The aim of this study was thus to describe the views on patient safety by operations managers and the establishment of patient safety and safety culture in somatic hospital care with the focus on what patient safety entails, what the operations managers do and how they organize feedback from the patient safety work into the organisation. Ideology, Goals and Principles in Patient Safety Work—A Theoretical Basis The ideology of patient safety work is that HMC is characterized by great openness, i.e., that there exists within the organisation a great willingness to report and the management clearly demonstrating its commitment. Openness also entails transparency regarding; for in- stance, results and quality, which means that care inju- ries are also reported publicly [10]. The goal of HMC is to benefit the patient which involves a complex process containing examinations and treatments fraught with risks in an increasingly high-tech environment [4]. The goal also comprises the development of safe systems, so that human errors and mistakes do not cause injuries to the patients [7]. The goal of patient safety work is also in- creasingly directed towards finding systematic reasons behind the errors that are committed [7]. The principle for attaining patient-safe care in operations demands a safety culture involving all actors in the activity viewing patient safety as the most important basis of operations development. Other principles include the existence of a report system which involves reporting incidents, as well as root cause and risk analyses that minimize risks and enable the changing of routines in order to avoid the repetition of negative events [10]. 2. METHOD 2.1. Design and Method Description A descriptive design with a qualitative approach in line with qualitative content analysis was carried out in so- matic healthcare in a South Swedish county serving a population of 189,000. Th e analysis was built on deduc- tive analysis, i.e., the analysis was performed on the ba- sis of predetermined themes [11]. Qualitative content analysis is used for interpreting texts where experiences, actions, explicit or implicit rules, codes or power struc- tures are in focus [12]. By exploring bo th a manifest and a latent analysis level an increasingly deep abstraction vis-à-vis the studied phenomenon is achieved. Manifest analysis deals with the surface, visualising components in the text, i.e., what the text says, whereas latent analy- sis concerns underlying meanings, i.e., what the text is about [12]. 2.2. Participants The selection comprised all the 29 operations managers, four of whom declined claiming lack of time or without giving any reason. The average operations manager was a man aged between 56 and 65. He w as a physician, who had been active either less than 15 or more than 26 years and an operations manager for 5 years or less (Table 1). 2.3. E-Mail Questions After five socio-demographic and situational questions followed four open questions on patient safety work: Which areas of patient safety work do you consider im- portant? How do you work with these areas in your or- ganisation (with staff, methods, etc.)? How do you measure the effect of this work? How does the patient safety work benefit the patient? These questions were worked out by the authors in consultation with the pa- tient safety steering committe e in the coun ty. All authors were well acquainted with both subject and method and were also aware of their own pre-understanding [13]. Two test interviews were carried out, resulting in a few linguistic adjustments. 2.4. Data Collection The e-mail questions, which were distributed via indi- vidual mail addresses, included an introductory letter describing the background and aim of the study. The informants’ answers, which were written down in the mail document itself comprised 10 - 25 lines. The gath- ering of data took place in November-December 2008. Two reminders were sent out after two and four weeks, respectively. 2.5. Data Analysis A data analysis was performed following a deductive approach [14], i.e., each question was analyzed sepa- rately [11]. In line with Graneheim and Lundman each text was read through several times to obtain an idea of its contents and enter into the total picture. Sentences and phrases by operations managers containing informa- tion relevant to the aim and to the individual questions were understood as meaning units. These meaning units were further condensed to enable a gross division of data for the purpose of discovering patterns in the responses made by the operations managers that could be linked together, like “avoiding scapegoat thinking”. When the meaning units of the text were extremely detailed, sub-  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 35 Table 1. The socio-demographic and situational background variables of the operations managers (N = 25). Variable Number Sex Male 18 Female 7 Age, years - 45 2 46 - 55 7 56 - 65 6 Number of years in organisation - 15 10 16 - 25 5 26 - 10 Number of years as operati o n s manager - 5 12 6 - 10 5 11 - 15 3 16 - 5 Highest educational le vel Physician 15 Specialist nurse 4 Physiotherapist 2 Engineer 2 Management and organisation 1 Teacher in health and medical care 1 categories were abstracted, like “system errors rather than individual errors”. Correspondingly, categories of subcategories were created with a view to highlighting the manifest contents so that, for instance, “system er- rors rather than individual errors” and “dialogue en- couragement” created the category “an open attitude to reporting”. The final part of the content analysis in- volved more tangible abstraction from the manifest to the latent level, i.e., finding and interpreting themes which linked categories together, such as “a permissible work climate in the team”. The authors conducted their analyses separately but solved the manifest as well as the latent analysis results in a common spirit of understand- ing, i.e. having >80% agreement on coding [14]. Alto- gether there emerged four themes describing the experi- ences of the operations managers and the establishment of patient safety in the organisation. 2.6. Ethical Considerations The study followed the Helsingfors Declaration guide- lines. In Sweden, ethical permission is not required unless the study invo lves ph ysical measures affecting the health of an individual [15]. It had, however, requested and received sanction both from the chief medical offi- cer and from the county control group for patient safety. Furthermore, the participants gave their consent through answering the questions. They were guaranteed that the material would be treated confidentially and that indi- vidual answers would not be traceable [16]. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Optimal Care Results for Each Patient (Table 2) To obtain the opti mal care result for each patient was th e operations managers’ intentio n in their daily work in the organisation. The areas pinpointed as important to pa- tient safety were associated with the basic mission of the organisation. The operations managers did not particu- larly emphasise a holistic view of patient care as impor- tant to patient safety. 3.1.1. Preempting Care Injuries The operations managers stressed the importance of preemptive work by creating an interest and developing continuous safety thinking among the staff. To be risk- conscious when, for instance, dealing with computer systems in everyday activities was considered one way of preempting care injuries. “Preemptive work is essen- tial. Identifying risks and thus avoiding that any indi- vidual or patient is injured”. Different work areas were pointed out by the operations managers in the context of attaining care safety by preempting patient injuries, i.e., injuries that could have been avoided. Safe medicine handling, hygiene and infection prevention, as well as preempting care-related infections, pressure wounds and fall injuries were examples of this. “It feels especially important not to cause patient injuries on top of the problems the patient is seeking a remedy for … unnec- essary and risky operations, which are unfortunately sometimes conducted in order to perform diagnostics all the way.” 3.1.2. Ensuring High Staff Competence Having a staff with a good, quality-assured competence is considered as being important to patient safety. Fur- ther staff education was given priority in the organisa- tion by promoting “clear routines, education, safe equipment and to safeguard having the right competence for our mission.” Guidelines and continuo us quality reg- istration existed within areas like hygiene and infection  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 36 Table 2. The analysis process of what patient safety entails for operations managers: from meaning units to a theme. Theme Category Subcategory Meaning unit Optimal care results for each patientPreempting care injuries Avoiding patient injuries Safe diagnosis/treatment (10) Safe medicine handling (8) Safe technology/equipment (5) Safe patient milieu (4) Risk awareness in handling computer systems Safe Cosmic use (3) Correct documentation (3) Preem p ting po ssib le complications Hygiene-infection protection (9) Preempting care-related infections (6) Fall injuries (4) Preempting pressure wounds (2) Ensuring high staff competenceQuality-assured competence Continuous further e duc atio n (10) Memos, care plans, care programmes (9) Safe routine s and work methods Cooperation processes with other units (4) Functioning deviat ion handling sy ste m s Deviation reporting/ event analysis/risk analysis (14) (n) = number of opera tions manage rs. protection, care-related infections and pressure wounds. It also emerged that cooperation processes and coordina- tion with other units were important for the development of safer care. There can be “coordination groups for effective processes benefiting the patient”. The operations managers stressed the importance of an open attitude and discussion, as well as a focus on organisational refinements. This was an important stage in the work on patient safety to be able to build up a well functioning way of handling deviations involving feed- back reporting by “encouraging the reporting of devia- tions and their feedb ack follow-up at e.g. ward and doc- tors’meetings”. Reporting deviations was an important instrument for capturing incidents and injuries within HMC. Root cause analyses were found in parts of the organisation as an instrument for preventing a recurrence of such events. Performing risk analyses to preempt risky situations was looked upon as a step in the devel- opment of patient safety through “working with devia- tions and root cause analyses as a basis for improve- ments whose aim is to find ‘system errors’, not pointing out ‘sinners’ and working with risk analyses before a new element is introduced”. 3.2. Permissive Working Climate among the Staff (Table 3) The operations managers expressed, albeit not exten- sively, that safety culture meant an open dialogue and communication, where a learning and reflecting ap- proach could lead to flexibility and to awakening an in- terest among the staff in patient safety work. Stimulating incident reporting, follow-up and feedback while avoid- ing an atmosphere of blame led to work team openness. An Open Attitude to Rep orting and Learning from Errors The operations managers realized the importance of al- ways keeping an open discussion about what had gone wrong or had been on the point of becoming a deviation. A reporting model indicating system errors rather than individual errors was viewed as a prerequisite for good safety culture: “Patient safety culture: incident reporting, daring to report and notify if anything is turning out wrong”. Following-up incidents in the management group, at doctors’ and ward meetings elucidated repeated errors. This resulted in encouraging an open dialogue and developing constant safety awareness among the staff: “A learning and reflecting approach to errors and deviations in teams and at the clinical level without scapegoat thinking”. 3.3. Continuous Organisation Development (Table 4) To attain safer care for the patient the operations man-  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 37 Table 3. The analysis process of what safety culture entails for operations managers: from meaning units to a theme. Theme Category Subcategory Meaning unit Permissive work climate among the staff An open att it ud e to reporting and learning from errors System error rather than individual error Avoiding scapeg oa t thinking (5) Encouraging dialogue Patient safety work underta ken in an open discussion (6) Visualising error s committedEncourag ing deviation reporting (4) Developing constant safety thinking (3) (n) = number of opera tions manage rs. Table 4. The analysis process of how operations managers implement work areas for patient safety: from meaning units to a theme. Theme Category Subcategory Meaning unit Continuous organisation development Working for o pt imal treatment outcomes Safe diagnostics/perform ance/ treatment Safe ty wor k-c a re control/diagnosis/treatment (11) Diagnosis/ treatment within reasonab l e time Diagnostics/performance/treatment (5) Ward rounds, dialogue with other unit s (4) Acting for high competence Quality-assured competence Continuous further e duc atio n (10) Safe routines and work methods Memos, care plans, care programme s (9) Local and national measurementsKUPP, MIG, ALERT, local and national r egister s (11) Developing the handling o f deviations Deviation repor ting Deviation repor ting/feedback (14) Risk/event analyses Enquiry into errors that have or could have occurred (3) (n) = number of opera tions manage rs. agers stressed the need of continuously developing the organisation. Prioritised areas included staff education, the development of standardised processes, participation in local and national quality measu rement, as well as the continuous handling and processing of incidents. 3.3.1. Wor king for Optimal Trea tment Outcomes There were operations managers that stated that safe diagnostics, treatment and care were a prioritised area when it came to patient safety in the organisation. “Safe operations without complications must be our focus and there is a lot to do there”. To ensure a right diagnosis within reasonable time necessitates prev enting delay and not performing unnecessary and risky operations, as well as preventing mix-ups and safeguarding the documenta- tion. “The patient should not have to su ffer care injuries, but should be able to be discharged in a recovered con- dition”. Operating units found it natural that the focus was laid on safe operations without complications to the benefit of other areas like medicine handling and care. 3.3.2. Acting for High Competence For everyday work the operations managers emphasised the importance of professional knowledge among the staff and of carrying out continuous further education in order to reach that goal. Updating memos, care plans and care programmes resulted in a continuous improvement of care routines and work methods. For the development of patient safety the importance of medical-technical safety was stressed, such as requiring a “licence” and quality control for all medical-technical equipment hav- ing “maximum competence in all professional categ ories involved e.g. demands fo r further education, the division into team-based a reas of respons ibility for mutual learn- ing and medical-technical safety, such as licences”. There were operations managers who emphasised the need for safe routines and the development of computer systems for medicine, referrals, test results and journal keeping as well as producing standardised processes for avoiding delayed diagnostics and mix-ups during testing and op- erating, for instance. Data gathering for local and na- tional quality registers was pointed out by operations managers as a working area for development which would result in safer HMC. “Registering post-operative wound infections is a good example of how patient safety work can be followed up”. Processes forming parts of measurements included wait-  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 38 ing-time registers, the follow-up of medical results, as well as comparisons with local and national registers. “Measuring the degree of observing hygiene rules is one measure”. There were operations managers who ex- pressed the need to do much more for developing patient safety in Swedish HMC, which people could advanta- geously learn from each other. “There are several pro- jects available that we could work with to increase pa- tient safety”. 3.3.3. Developi n g t he H andling of Deviations The operations managers were aware of the need to stimulate all colleagues to report incidents, since a great deal of concealed information had to be made visible before any change could take place. “The number of re- ports increases, but I think that is right so far.” Having access to an incident reporting system where colleagues report, handle and feedback the results into the organisa- tion was pointed out as one area for developing safer care. In “following up deviations” and “reflection during various meetings” “repeated errors become visible”. Further areas towards improved patient safety included the development of risk and root cause analyses. The operations managers pointed out the difficulty of using material gathered from deviation reporting to the fullest. What was missing was, for example, measuring instru- ments for evaluating the effect of the work in it being “hard to measure. If deviations that used to be common disappear, this may hopefully be the result of improve- ments made”. 3.4. From Recovered Patients to a Shorter Care Time (Table 5) The operating managers’ goal with regard to patient safety work was that it increased quality of care. This meant adequate and safe diagnostics and treatment, leading to fewer complication s and a shorter care time. 3.4.1. Continuous Development of All Work Elements The operations managers stated that making efforts to continuously develop all work elements ensured effec- tive and good quality of care. This led to fewer erro rs in the organisation and improved care outcomes, which benefited patients directly, for example, by shortening the care time “through safer and better planned care where we do all we can to avoid mistakes”. “Structuring and observing routines hopefully save both time and health for our patients!” There were operations manag- ers who expressed the importance of a joint measuring instrument in order to get a firmer grasp of whether their own activities were on the right track towards patient safety. It is “much harder to measure the effect of the work. This is where the organisation needs help!” 3.4.2. Building Barriers to Prevent Recurring Errors There were operations managers who expressed that all HMC entailed a risk and that every treatment must be evaluated from the injury risk perspective. They stated that adequate diagnostics and treatment with fewer com- plications led to shorter waiting, processing and treat- ment times, resulting in turn in safer care. It will be Table 5. The analysis process of how operations managers feedback patient safety w ork to the benefit of the patient: from meaning units to a theme. Theme Category Subcategory Meaning unit From recovered patients to shorter care time Continuous development of all work elements Adequate car e Adequate and safe diagnostics and treatment (12) Lack of measuring instruments“Hard to measure”, “La ck in g in st ruments”, “No eff icie nt measurements”, “No measuring” (11 ) Shorter care time Shorter waiting, proc essing and treatment times (8) Fewer errors committed Fewer complications (5) Building barriers to prevent recurring errors Quality measurement feedbackReporting the result of KUPP, MIG, ALERT, local and national registers (11) Deviation result feedback Me a suring regi stere d and remedied deviations (10) Safer care Patients should not have to suffer care injuries (7) Patients should be able to be discharged in a recovered condition, each treatment should be evaluate d from the injury risk perspective (5) (n) = number of opera tions manage rs.  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 39 “safer and more secure care, I hope. This, at least, is my driving force”. The operations managers pointed out that feeding back the results of quality measurements and deviations developed the care and prevented recurring errors. Another beneficial effect was that patients did not suffer any care injuries but were discharged in a recov- ered state of health. “The patient should not be made to suffer from care-related infection s, pressure wo und s, fall injuries etc., but should be able to be discharged after being clearly recovered!” 4. DISCUSSION 4.1. On Method A qualitative study needs to be reflected from the per- spective of trustworthiness [17], which comprises the concepts of credibility, dependability, transferablity and confirmability. Credibility refers to how a satisfactory selection and choice of method has captured the aim. An established method, partaking of and being able to de- scribe and interpret individual experiences, attitudes, views, etc. of a given phenomenon (patient safety) was chosen i.e. qualitative content analysis [12]. The target for studying this phenomenon was operations managers, which must also be considered most relevant taking into consideration that they were responsible for maintaining and developing patient safety within the organisation. Dependability refers to factors that may affect the actual gathering of data. In this case the data gathering was conducted via e-mail questions which meant that it was impossible to ask in-depth questions. Although this was a limitation, it did give all operations managers the op- portunity to participate which may add positive weight to the data gathered. One possible risk was that the op- erations managers would present an ideal instead of the actual picture of patient safety work. However, this did not at all appear from the result. The e-mail questions had been preceded by two test interviews carried out with only minor adjustments afterwards. Transferability means to what extent the result may be transferred to other milieus and people. From a statistical point of view the result cannot be generalized, but since practically every operations manager within somatic healthcare par- ticipated, the result has great importance for good trans- ferability to other somatic healthcare. Confirmability indicates that the data is treated as objectively and neu- trally as possible and involves balancing the data con- tents against the researchers’ prior understanding. The authors were well aware of and reflected on their prior understanding of the method, as well as of the knowl- edge area. They read the texts separately and were care- ful to distinguish between manifest and latent contents, as well as to reach joint consensus on all levels i.e. reaching a reasonable agreement of 80 % [14]. 4.2. On Results 4.2.1. Optimal Care Outcome for Each Patient Operations managers describe that production is the main task of their work and that patient safety is linked to production. They find it natural that other areas, such as medicine handling, correct documentation and safe patient care and environment take second place. Right up to the 21st century the quality o f HMC was evaluated by comparing production outcome and patient outcome i.e. the process-related result [18]. Comprehensive pa- tient safety work has, howev er, changed th e view of how to attain safe care. The development of quality indicators, measuring instruments revealing the quality of the care offered and local improvements turn out to have a bene- ficial effect on the occurrence of negative events. The quality perspective shows that safe care is not only a question of avoiding injuries in connection with medical measures, but also includes other care, risks and work elements to which the patient is subjected [19,20]. The majority of the operations managers in this study are physicians. This may be one reason for the gradual pa- tient safety work, since the culture of HMC is character- ized by professional autonomy, which counteracts coop- eration among the staff, which is a prerequisite for cre- ating safe care [21]. Steadfastness among physicians towards improvements can be attained in light of the focus in their education on professional knowledge to focus on both professional knowledge and improvement knowledge (teamwork, psychology and learning-based improvement work) which are required to achieve an effective HMC [22]. The operations managers’ views is that preemptive safety work is taking place within areas aiming at a high competence among the staff and at han- dling deviations and preempting care injuries. Care inju - ries are underreported which makes it important to de- velop a report system and not in the least to learn from the reported events. It is essential to u nderstand why and how things go wrong and to find system errors instead of individual errors in order to obtain increased patient safety [23]. 4.2.2. Permissive Work Climate among the Staff A safety culture involves an open dialogue and commu- nication within the work team, but there are few opera- tions managers who highlight the importance of safety culture within their domains. Research on the role of leadership in quality improvement is rare [24], although the leader must possess willingness for improvement and be able to build systems and operate staff development [25]. Effective leadership has an impact on the precondi- tions for achieving quality improvements. Enhancing commitment to these improvements is required, as well as increased proficiency in the cooperation in the system  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 40 regarding these matters and creating clear goals for pa- tient safety work [21]. A culture which supports and promotes safety is identified as a key factor for improv- ing patient safety. A safety culture demands that balance is obtained between the system and the ind ividual which means that healthcare professionals are responsible for their activities when it comes to conducting systematic patient safety work [26,27]. A safety culture or policy is necessary before other patient safety methods are intro- duced. Otherwise, individuals are expected to implement safety before the staff knows how they work best to- gether and communicate most effectively [26]. To con- tinuously evaluate the safety cli mate and the attitudes of the staff is thus necessary in order to maintain the patien t safety culture in a workplace. The self-evaluation in- strument Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture fo- cusing on systems and the responsibility of staff is a good example of this essential point [26,28]. 4.2.3. Continuous Orga ni sa tion Development Operations managers describe the importance of con- tinuously developing the organisation with regard to processes, produ ction an d staff ed ucation for th e purpos e of attaining greater care safety. In connection with the increasing complexity of HMC where the medical de- velopment heightens the possibility of and the demand for curing previously life-threatening diseases, deficien- cies in the management structure, work process and staff competence level entail a great risk for patient safety [29]. In this study there is great belief in local memos, care routines and care programmes among the operations managers, whereas communication and cooperation are rarely mentioned as important work areas for patient safety. A study including 2000 reported deviations shows that half of the incidents were related to staff compe- tence and a third of the incidents to deviations from memos and standardised care routines [19]. Another important reason behind the reported events is the lack of communication. One fifth of the incidents have been shown to be caused by poor communication between patient and individual staff. Half of the incidents reflect a lack of communication between members of the staff [30]. A recurrent observation among the operations managers is the importance of quality measuring and deviation reporting. A good report system is the basis for developing risk assessment in HMC. The reporting of incidents needs to include all sorts of incidents and not just serious injuries to the patient [19,31]. The operations managers refer to the national project for bringing down the frequency of care injuries of six types which com- prises, among other things, reducing the occurrence of care-related infections by half before the end of 2009. The fact that quality measurements improve patient safety is shown by the description of results from the Institute of Healthcare Improvement located in the United States where a packag e of measur es for the major safety problems within acute healthcare was implemented in- cluding, for instance, care-related infections and medi- cine side effects. The result showed a 15% reduction of mortality and a 60% reduction of ventilator-associated pneumonia [32]. 4.2.4. From Recovered Patient to a Shortened Care Time The goal of patient safety work, according to the opera- tions managers, is a recovered patient with fewer com- plications in a shorter care time. At the same time meas- urement instruments are requested for the purpose of finding out whether patient safety work is on its right way. This means a demand for increased knowledge, application and national follow-up of the measurement tools available. The degree of satisfaction with existing tools is high, but further development is required to ob- tain a holistic view of care safety, quality of care and results [33]. The HMC managers need to set up clear national goals raising patient safety to becoming an issue as important as the budget. Well-defined goals make higher claims on commitment and efficient cooperation within the system which is a prerequisite for developing safety culture [21,34]. A change of attitude among the HMC managers is needed to create a willingness and rally forces to realize the proposed goals [20]. Further areas which Swedish HMC need to apply from the United States to increase patient safety include team- work and involving patients and their relations through information on committed care-related mistakes, as well as to encourage patients and their relations to be active in asking questions [21,23]. 5. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS Operations managers within somatic healthcare regarded production as the most important task, thereby linking patient safety directly to the basic mission. The majority of the operations managers were physicians which may be one reason why professional knowledge was reflected in the areas chosen for safety work in the organisation. Safety work means attaining the optimal care outcome for each patient by the continuous development of the organisation. Their goal was to reach this by working for a high competence among the staff, having a functioning way of handling deviations and preempting care injuries. Safety culture, which was very sparsely mentioned, laid emphasis on the importance of a permissive work cli- mate with an open attitude to reporting and learning from errors. The operations managers’ goal of patient safety work was that it increased quality of care entailing fewer complications and a shorter care time. Further studies are needed on the views of operations managers  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 41 on patient safety work within their organisation, espe- cially on why managers do not give priority to patient safety work and on what measures need to be taken. An- other research implication is to study the direction of patient safety work when the operations manager is not a physician. A clinical implication is to make patient safety think- ing a primary issue instead of the current focus on high competence in the belief that this leads to higher patient safety. It is further proposed that patient safety is in- cluded in the basic education of all healthcare profes- sionals. To construct an emphasis on the system com- posed of collaborating individuals requires research on communication, teamwork and clinical decision-making, supplementing a focu s on high competence, good equip- ment and the impact of routines on patient safety. REFERENCES [1] Powell, S. (2004) Patient safety: It’s not just carefulness, it’s a culture. Lippincott’s Case Management, 9, 211-212. doi:10.1097/00129234-200409000-00001 [2] Sandars, J. (2007) The scope of problem. ABC of Patient Safety. Blackwell Publishing Inc., Malden. [3] Kohn, L.T., Corrigan, J.M. and Donaldson, M.S. (1999) To err is human. Building a safer health system. Institute of Medicine. The National of Academic Press. www.iom.edu [4] Pace, W. (2007) Measuring a safety culture: Critical pathway or academic activity? Society of General Inter- nal Medicine, 22, 155-156. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0061-8 [5] Soop, M., Köster, M., Fryksmark, U. and Haglund, B. (2008) Health care injuries to hospital care are com- mon—The majority can be avoided, shows study of jour- nals. Swedish Medical Journal, 105, 1748-1752. [6] The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. (2009) Patient and client safety/Health care injuries. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Stock- holm. www.socialstyrelsen.se [7] Rutberg, H. and Weeks, W. (2004) Massive effort to improve patient safety in the United States. Swedish Medi- cal Journal, 101, 2276-2278. [8] Öhrn, A., Andersson, C., Elfström, J., Liedgren, C. and Rutberg, H. (2007) Success requires managers’ support and resources. Swedish Medical Journal, 4, 224-228. [9] Denham, C.R. (2005) Patient safety practices: Managers can turn barriers into accelerators. Patient Safety, 1, 41-55. doi:10.1097/01209203-200503000-00009 [10] The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. (2004) Patient and client safety. Publications/patient safety and patient safety work. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm. www.socialstyrelsen.se [11] Hsieh, H.F. and Shannon, S. (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687 [12] Graneheim, U.H. and Lundman, B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, proce- dures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105-112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [13] Nyström, M. and Dahlberg, K. (2001) Pre-und erstanding and openness—A relationship without hope? Scandina- vian Journal Caring Sciences, 15, 339-346. doi:10.1046/j.1471-6712.2001.00043.x [14] Bradley, E.H., Curry, L.A. and Devers, K. (2007) Quali- tative data analysis for health services research: Devel- oping taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42, 1758-1772. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [15] World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, Seoul. (2008) Ethical principles for medical research in- volving human subjects. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, Seoul. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/ [16] Swedish Research Council/University of Uppsala. (2007) CODEX—rules and guidelines for research. Swedish Research Council and University of Uppsala, Uppsala. WWW.CODEX.uu.se [17] Lincoln, Y.S. and Guba, E.G. (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage, Beverly Hills. [18] Pronovost, P., Miller, M. and Wachter, R. (2006) Track- ing progress in patient safety. Journal of the American Medical Association, 296, 696-699. doi:10.1001/jama.296.6.696 [19] Pronovost, P., Thompson, D., Holzmueller, C., Lubomski, L., Dorman, T., Dickman, F., Fahey, M., Steinwachs, D., Engineer, L., Sexton, J., et al. (2006) Toward learning from patient safet y reporting systems. Journal of Critical Care, 21, 305-315. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.07.001 [20] Sheikh, A., Baker, M. and Thomson, R. (2007) Future Directions. ABC of Patient Safety. Blackwell Publishing Inc., Mal den. [21] Leape, L. and Berwick, D. (2005) Five years after to err is human: What have we learned? Journal of the Ameri- can Medical Association, 293, 2384-2390. doi:10.1001/jama.293.19.2384 [22] Rutberg, H. Sommer, A.H. and Skau, T. (2001) Quality in health care. What is it and how it is measured? Swed- ish Medical Journal, 98, 3044-3045. [23] Baker, D.P., Salas, E., King, H., Battles, J. and Barach, P. (2005) The role of teamwork in the professional educa- tion of physicians: Current status and assessment rec- ommendations. Joint Commission Journal Quality Patient Safety, 31, 185-202. [24] Weingart, S.N. and Page, D. (2004) Implications for practice: Chall enges for healthcare managers in fostering patient safety. Quality Safety Healthcare, 13, 52-56. doi:10.1136/qshc.2003.009621 [25] Övretveit, J. (2005) The managers role in quality and safety improvement. www.landstingsförbundet.se [26] Lewis, R.Q. and Fletcher, M. (2005) Implementing a national strategy for patient safety: Lessons from the Na- tional Health Service in England. Quality Safety Health- care, 14, 135-139. [27] The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. (2008) Publications/social welfare board referral, res- ponse to the report Patient what has been done? What needs to be done? The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm. www.socialstyrelsen.se. [28] Flin, R., Burns, C., Mearns, K., Yule, S. and Robertson,  G. Karlsson et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 1 (2011) 33-42 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJN 42 E. (2006) Measuring safety climate in healthcare. Quality Safety Healthcare, 15, 109-115. doi:10.1136/qshc.2005.014761 [29] Rinder, L., Soop, M. and Steen, L. (2004) Patient safety and patient work. Knowledge overview. www.socialst yrelsen.se [30] Beyer, M., Rohe, J., Nicklin, P. and Haynes, K. (2007) Communication and patient safety. ABC of Patient Safety. Blackwell Publishing Inc., Malden. [31] Runciman, W., Edmonds, M. and Pradhan, M. (2002) Settings priorities for patient safet y. Quality Safety Health- care, 11, 224-229. doi:10.1136/qhc.11.3.224 [32] Botwinick, L., Bisognano, M. and Haraden, C. (2006) Managership Guide to Patient Safety. www. IHI.org [33] Mannion, R., Konteh, F.H. and Davies, H.T.O. (2009) Assessing organisational culture for quality and safety improvement: A national survey of tools and tool use. Quality Safety Healthcare, 18, 153-156. doi:10.1136/qshc.2007.024075 [34] Colla, J., Bracken, A., Kinney, L. and Weeks, W. (2005) Measuring patient safety climate: A review of surveys. Quality Safety Healthcare, 14, 364-366. doi:10.1136/qshc.2005.014217 |