Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

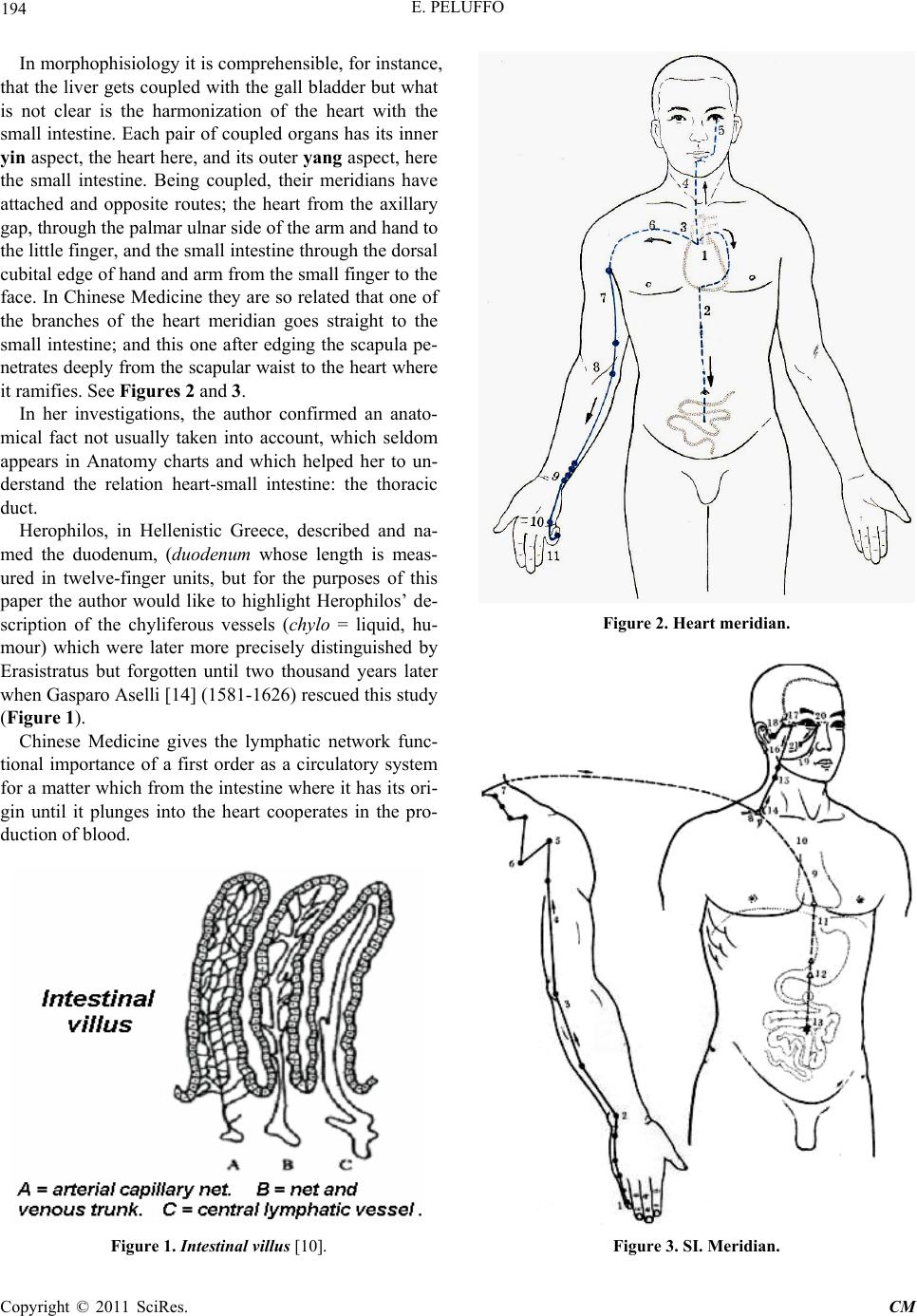

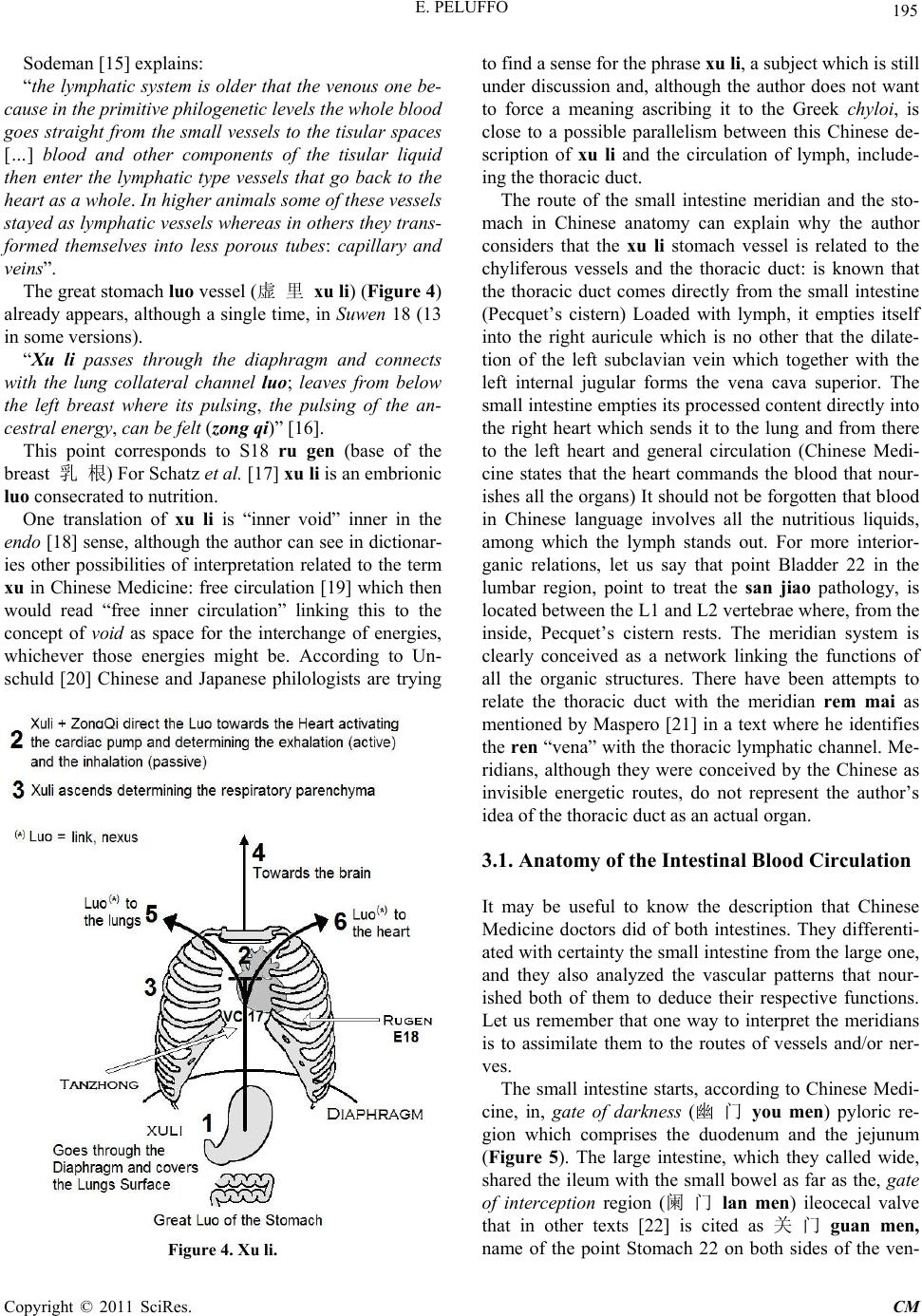

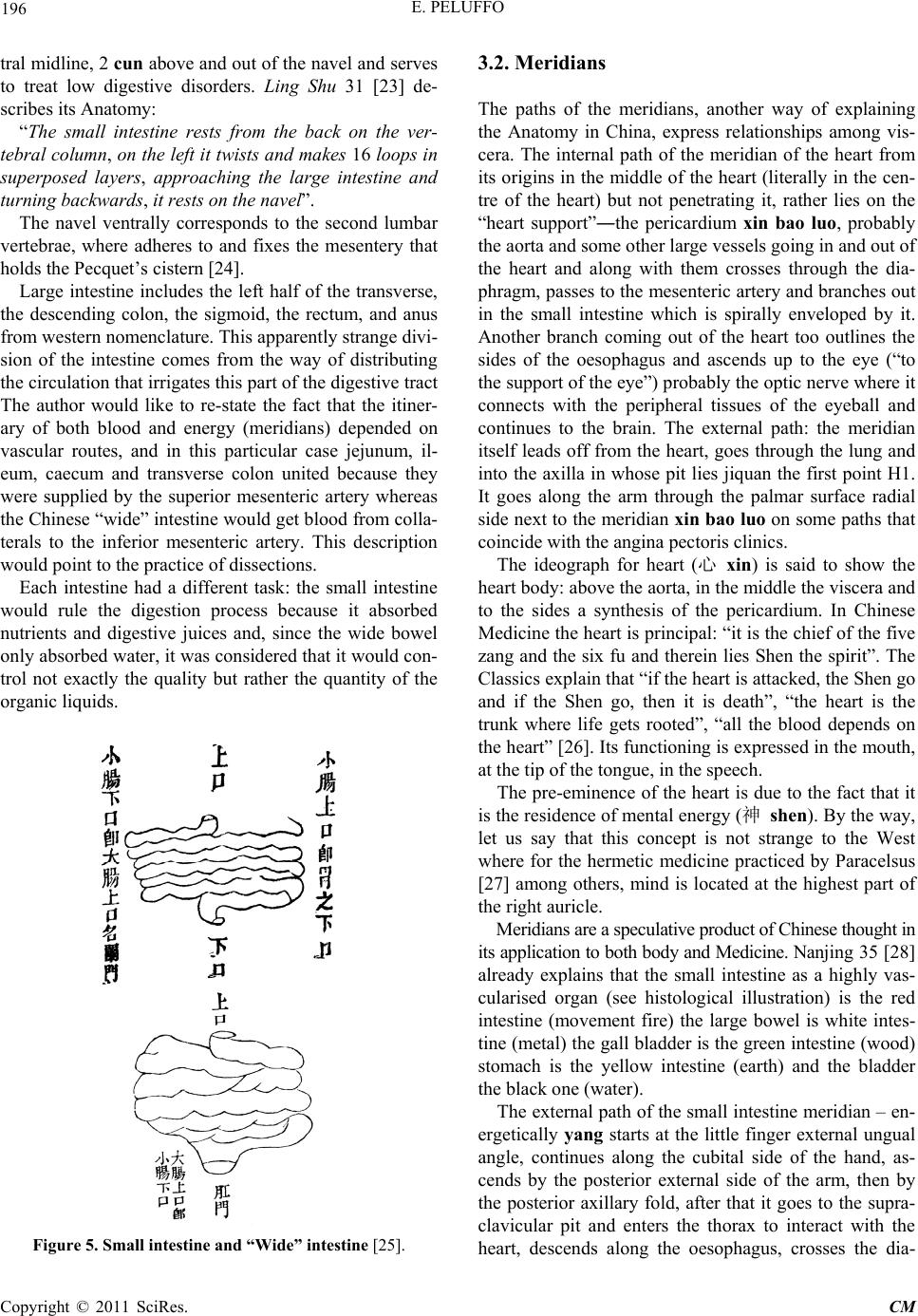

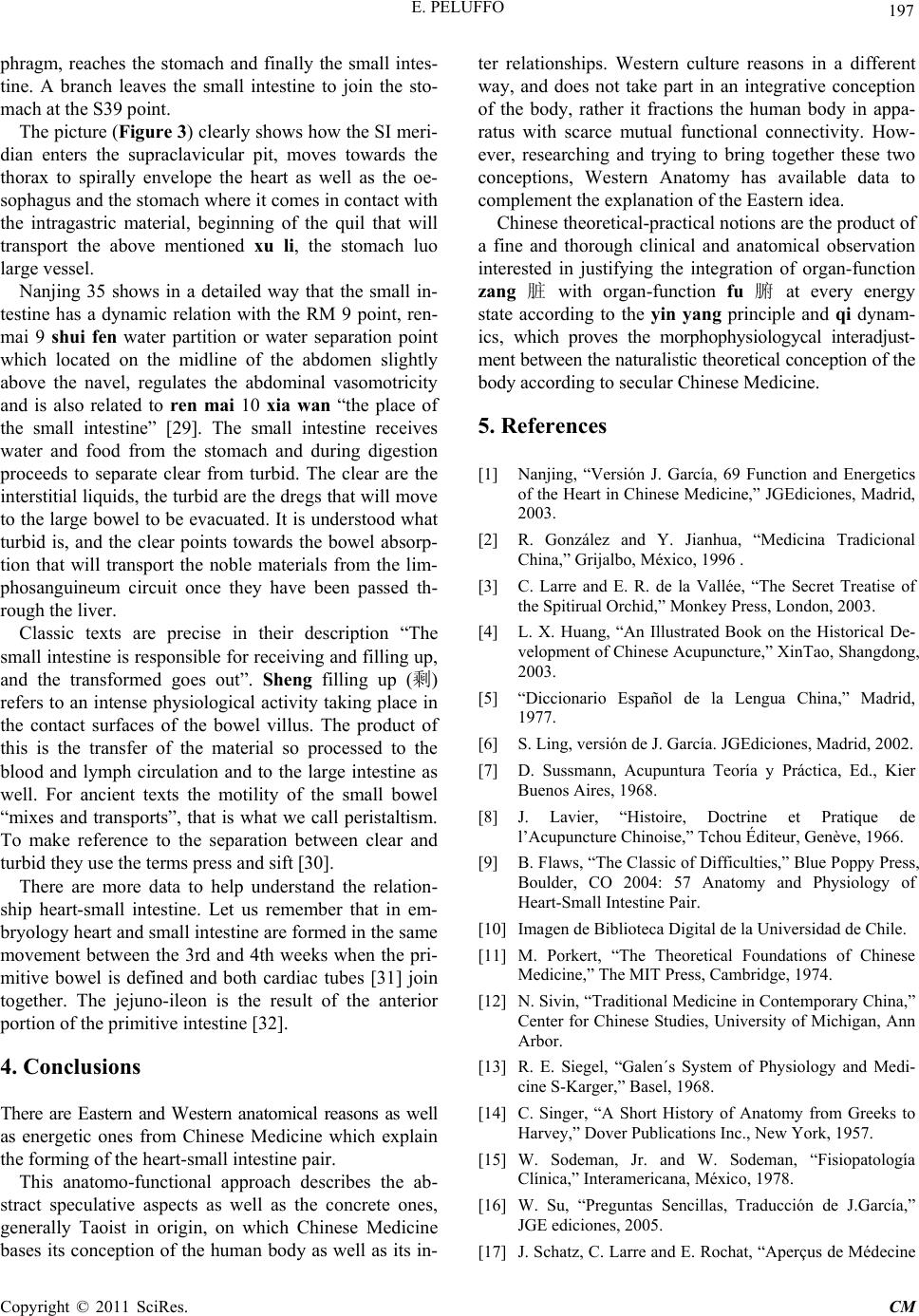

Chinese Medicine, 2011, 2, 191-198 doi:10.4236/cm.2011.24030 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/cm) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. CM 191 The Pairing of Heart and Small Intestine Xin Xiao Chang Xiang Biao Li 心 小 肠 相 表 里 Electra Peluffo Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain E-mail: acupuntura@electrapeluffo.com Received March 1, 2011; revised April 1, 2011; accepted April 18, 2011 Abstract This paper investigates the reasoning, based on both Chinese and Western medical data, which will lead to an understanding of the relation of the heart and small intestine, organs which Chinese Medicine, in the Fire energy phase, link both functionally and anatomically. The direct relationship between the liver and the gall bladder and between the kidneys and the bladder is recognised and accepted in both Chinese and Western Medicine. This is not the case with the pairings which in Eastern morphophisiology are formed by the heart and small intestine and the lungs and large intestine. These pairings are not recognised in Western Medicine. The writer in her dual capacity of Doctor of Western Medicine and acupuncturist is investigating the reasons why in Chinese Medicine the heart and small intestine and their meridians form a relation which couples them. For this the comparative method was used between data from Western anatomy which demonstrate the interorganic and functional relation between the small intestine and the heart and the Chinese energy dyna- mic of the corresponding zangf u and jingluo. Biomedicine which does not relate the heart with the small intestine brings in the materiality of its anatomic descriptions which are valuable for the interpretation of Oriental Medicine. This interrelation between the two organs and their meridians are well explicated in Chinese Medicine whose traditional concepts in this respect are corroborated by Western anatomical des- criptions which, nevertheless, do not admit the functional-organic coupling of the heart and small intestine. Keywords: Organic Pairing, Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, Classic of Difficulties, Heart, Small Intestine, Thoracic Duct 1. Introduction Zangfu process the functions which are linked to the es- sentials energies: breathing and eating. Zangfu constitute functional units of coupled pairs. They are dynamisms which because they are located in certain areas of the body, induce to associate them with the organs seen from a Western view. But such coincidence is not complete since the functions described in China are not restrained to a certain area and they significantly exceed the cor- respondent topography. Each Zangfu pair is just one more yingyang couple. The heart-small intestine pair shares the fire move- ment with another “organic” pair of imprecise anatomic base and untranslatable name despite various attempts of European languages to do so, it is xin bao luo―san jiao: difficult to define and whose presence we shall try to interpret. Chinese Medicine for its fire phase links, both func- tionally and anatomically, the heart with the small intes- tine and during the metal phase the lungs with the large intestine. Nanjing difficulty 35 [1] describes: “The 5 viscera each have a place… and the bowels are close together, only the heart and lungs are removed at a distance from the small and large intestines.” And gives reasons for this: the heart is responsible for nutrition and the lungs for defence, and both commu- ni- cate and move (tong 通 - xing 行) the yang energy and that is why they are located in the yang area at the top of the trunk. Both intestines transmit the yin energy down- wards and therefore they are located in the lower part (yin) Likewise, the small intestine anatomically is central, as the heart is, and the large one is lateral as lungs are. The small intestine is the bowel (腑fu) of abundance, receives the surplus of the bowels and the large intestine is the bowel (腑fu) of transmition and drainage of this surplus.  E. PELUFFO 192 2. Function and Energetics of the Heart in Chinese Medicine In Chinese Medicine four names or expressions define the wide cardio-circulatory function 1) heart (xin); 2) centre of chest (膛 中 tang zhong) mediastinum; 3) that by which the heart commands (心 主 xin zhu); and 4) mesh which surrounds the heart (心 包 络 xin bao luo). Heart xin is the Emperor; the great chief of the body since it supervises and controls all the organic sectors and due to its functions, irrigates and nurtures even the tiniest corners of the organism through its circulation. This dynamic involves the movement of organic liquids, notably the blood and lymph. It is important to un- der- stand the Chinese meaning of the term xue, blood, which is not only the red liquid that runs through arteries and veins but, rather it designates all kinds of body secretions, hormonal secretions included as well as the transforma- tions produced in the interior of the body. Acupuncture point RM 17 ren mai 17 (膛 中 tang zhong “in the middle of the chest”) is a very important place of exchange of energies and at the same time the area where the heart resonates between the 2nd, 3rd and 4th intercostal spaces hosting three acupuncture points: RM 17, 18 and 19 which in the centre of the sternum relate to large vessels. Through tang zhong [2] runs the ancestral energy (zong qi 宗 气) that mediates between the genetic lineage we come from and the singular being we are, and which is also known as thoracic energy since it is stored in the centre of the chest, centre which is none other than tang zhong, even though in fact more than being the centre of the chest it is the chest as a centre [3]. Ancestral energy (zong qi 宗 气) comes up here through the large stomach luo vessel (xu li 虚 里) which anatomically we think corresponds to the lym- phatic circuit of the small intestine. Tang zhong centre or sea of upper energy (also called膳 中 shan zhong) has also the meaning of a container filled with fat that smells (shan means ram smell) Tan the fat whether it be in cholesterol or lymph form tends to have a strong and particular odour. The variation in names of structures, points and func- tions is traditional in Chinese Medicine. Professor Hu- ang in his thorough book [4] on imagery and artwork of meridians and acupuncture points tells us that as a result of the fact that numerous and diverse schools of acu- puncture of the pastthe author here thinks something similar is happening nowadays developed different the- ories and practices, the same name could refer to differ- ent points, different points could correspond to the same name, and moreover, numerous old point locations are currently unknown. There are more meanings of tan: bile, gall. Tan is also the inner lin ing of an object, e.g. the bladder of a football bladder [5] (metaphor of the thorax here?) which would suggest a membrane (pericardial, endocardial, pleural). A link between all meanings and denominations is es- tablished when Lingshu 35 [6] says that tang zhong is the Imperial palace of that by which the heart commands, that is none other than the above mentioned xin zhu, that by which the heart commands. The phase fire (火 huo) along with heart and small intestine has two other organs or functions: xin bao luo pericardium (imprecise translation) and triple heater (三 焦 san jiao) term which also has a difficult univocal translation to our European languages. As it happens heart and xin bao luo (possibly pericar- dium) work in unison as a single circulatory organ, and thus the four names we have analyzed above actually refer to the same functional notion of interchangeable anatomical basis. When treating with acupuncture it is often advised not to use points of the heart meridian but rather use the xin bao luo ones “so as not to disturb the emperor” [7] since both tracts points treat very similar symptoms. The author understands that xin bao luo is a function associated to xin heart and through it to the small intestine, but since in yin yang structure it is im- possible to be without a pair, xin bao luo gets paired up with san jiao which is a nearby visceral system, neigh- bouring in topography and with an anatomical base of membranes and envelopes related to the pericardium membrane. Xin zhu another name for xin bao luo (the protective wrapping of the heart and hence its importance) refers to another facet of its function because zhu is the one who holds the authority, decides, administers, reigns, rules, that is the mastery the heart exercises as holder of the sovereign fire (君 火 jun huo) . Xin is heart, bao is to wrap, to contain, to take control and luo is net, mesh, therefore xin bao luo is a ramifica- tion which inside the fire movement is minister fire (相 火 xiang huo) Xin bao luo is the function by which the hearts rules, not only there on the site but in the distance as well. Because of the latter Lavier [8] suggests the analogy of xin bao luo with the sympathetic system re- lating san jiao with the parasympathetic one. Nanjing 25 [9] when dealing with the subject of xin bao luo―san jiao couple insists on the fact that both have a name but not form because the pairing combines firstly visceral systems and secondly circulatory tracts (meridians). This matter about having no form is not new because before linking san jiao with xin bao luo, the first one was as- cribed to ming men, the immaterial energetic area be- tween the two kidneys where the ancestral energy moves. In the constant search of the necessary harmony that this Copyright © 2011 SciRes. CM  193 E. PELUFFO function needs, the working of the ming men area (there is no organ) is generally attributed to the hormonal yang right kidney whereas the yin left kidney is urinary. In ming men resides the source (原 yuan) the origin of every human being and that is the reason why it is a region where energies, quite mobile, get transformed and evolve. San jiao originates in that source, ming men. We have just described two symmetrical spaces: tang zhong between the two lungs and ming men between the two kidneys, without organicity, only functional, with an important energy charge of great mobility, one at the top of the splanchnic cavity―thorax and another one in the lower part, the pelvic area. 3. Anatomy and Physiology of Heart-Small Intestine Pair The explanation of the relationship between heart and small intestine has, in the author’s opinion, anatomical foundations from Chinese Medicine with outstanding physiological bases and we also have, along with the Chinese background, anatomical reasons recognized in the West. Irrigation, the blood perfusion of the small intestine was and is very prominent; practically the blood is in direct contact with the bowels content; that is to say that from the duodenum (which is part of the stomach according to the Chinese medical thought) everything is blood and quil (lymph). In Histology the intestinal villus contains an arteriole, a venule, a quil vessel, a nerve. Both Heart and Small Intestine belong to the move- ment fire, heart the emperor (imperial fire) expresses itself upward, towards the sky and its pair the small in- testine catalyzes downward the ashes of what was burnt on the way up. H. and SI. share this energy phase with xin bao luo and san jiao, exceptional circumstance since each phase is covered by only one pair of organs. But, the fact is that movement fire is divided into two hierar- chies: sovereign fire and minister fire and each visceral pair corresponds to a category. Wu Yun movements (wood, fire…) are five. Liu Qi climatic energies (wind, heat, dampness…) add to six. Both combined form the Wu Yun Liu Qi theory (五 运 六 气) also known to simplify, as Yun Qi. In this way one of the six energies would remain without organic representation. Then, it is likely that the unfolding of the fire phase arose from the search for symmetry in order to keep the pairings. Both Suwen not mentioning even once the name xin bao luo and Lingshu doing it only in refer- ence to meridians or acupuncture support the hypothesis that fire was duplicated only for organ pairing reasons [11]. What both books (Suwen 8 and Lingshu 35) re- peatedly mention is the place-point tang zhong we saw above attributed to ren mai 17 but functionally related to xin bao luo. The author personally thinks that although there seems to be no organ to link it to xin bao luo, it seems to be a place for tang zhong (the mediastinum) as there is a without-organ place between both kidneys for ming men, a function closely related with xin bao luo and san jiao. Places and spaces are also Anatomy. At the same time, it is not clear whether the Chinese described a specific organic substrate for xin bao luo which although not an organ is generally associated with the heart for its topography, the similarity of clinical symptoms and its pairing with san jiao, its yang com- plement in this fire movement and whose organic base would be the system of membranes of the thoraco-ab- dominal cavity (pleura, peritoneum, aponeurosis, fascias, mesentery, diaphragm) The membrane serving as a yin counterpart of these san jiao envelopes would be xin bao luo, thus it is named pericardium in many texts. This elaboration of the subject adds reasons to the pairing of the heart and the small intestine because, if the pericar- dium is closely associated to the heart and most part of the peritoneum (san jiao) to the small intestine, both membranes belong to the same fire movement and therefore its functions (and meridians) fit together. The author personally has doubts: if san jiao is pleura and peritoneum (parietal, visceral) what is the reason for it not being the pericar- dial membrane as well? That is to say: does san jiao need a parietal support to be itself? Would it lack that support in the pericardium? Or is this morphofunctional pair a necessity in ancient China to explain organic material (membranes) which they em- pirically checked at the thoraco-abdominal cavity but could not attribute to any specific viscera? Li Chan wrote Yi Xue Ju Men (Introduction to Medi- cal Studies) in 1575 [12] and one of its paragraphs can shed light on the subject as it is clear that the author at- tended dissections and describes what can be recognized as the fibrous external layer of the pericardium and as- signs the inner serous layer to the cardiac system: “The yellow- or brown-fatty substance (huang chih 黄 眙 ) that spreads and envelopes (the heart) b elongs to the cardiac system. Outside this spreading fatty subs- tance there is a fine sinewy silk-fiber-like membra ne connected to the lung system and to the cardiac and pulmonary systems; this is the Envelope Junction xin pao”. Sivin, translator of the Chinese text into English, warns that Li Chan writes uterus (胞 bao) and not wrapping (袍 pao) the ideographs have similar components and are, of course, homophones. It is not easy to write Chi- nese using only phonetics. Let us remember that also for Galen the pericardium is analogous to the protective structures (peritoneum and meninges [13]) due to its two layers which, overlapped at the base of the heart, allow its free contractility. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. CM  E. PELUFFO 194 In morphophisiology it is comprehensible, for instance, that the liver gets coupled with the gall bladder but what is not clear is the harmonization of the heart with the small intestine. Each pair of coupled organs has its inner yin aspect, the heart here, and its outer yang aspect, here the small intestine. Being coupled, their meridians have attached and opposite routes; the heart from the axillary gap, through the palmar ulnar side of the arm and hand to the little finger, and the small intestine through the dorsal cubital edge of hand and arm from the small finger to the face. In Chinese Medicine they are so related that one of the branches of the heart meridian goes straight to the small intestine; and this one after edging the scapula pe- netrates deeply from the scapular waist to the heart where it ramifies. See Figures 2 and 3. In her investigations, the author confirmed an anato- mical fact not usually taken into account, which seldom appears in Anatomy charts and which helped her to un- derstand the relation heart-small intestine: the thoracic duct. Herophilos, in Hellenistic Greece, described and na- med the duodenum, (duodenum whose length is meas- ured in twelve-finger units, but for the purposes of this paper the author would like to highlight Herophilos’ de- scription of the chyliferous vessels (chylo = liquid, hu- mour) which were later more precisely distinguished by Erasistratus but forgotten until two thousand years later when Gasparo Aselli [14] (1581-1626) rescued this study (Figure 1). Chinese Medicine gives the lymphatic network func- tional importance of a first order as a circulatory system for a matter which from the intestine where it has its ori- gin until it plunges into the heart cooperates in the pro- duction of blood. Figure 1. Intestinal villus [10]. Figure 2. Heart meridian. Figure 3. SI. Meridian. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. CM  195 E. PELUFFO Sodeman [15] explains: “the lymphatic system is older that the venous one be- cause in the primitive philogenetic levels the whole blood goes straight from the small vessels to the tisular spaces […] blood and other components of the tisular liquid then enter the lymphatic type vessels that go back to the heart as a whole. In higher animals some of these vessels stayed as lymphatic vessels whereas in others they trans- formed themselves into less porous tubes: capillary and veins”. The great stomach luo vessel (虚 里 xu li) (Figure 4) already appears, although a single time, in Suwen 18 (13 in some versions). “Xu li passes through the diaphragm and connects with the lung collateral channel luo; leaves from below the left breast where its pulsing, the pulsing of the an- cestral energy, can be felt (zong qi)” [16]. This point corresponds to S18 ru gen (base of the breast 乳 根) For Schatz et al. [17] xu li is an embrionic luo consecrated to nutrition. One translation of xu li is “inner void” inner in the endo [18] sense, although the author can see in dictionar- ies other possibilities of interpretation related to the term xu in Chinese Medicine: free circulation [19] which then would read “free inner circulation” linking this to the concept of void as space for the interchange of energies, whichever those energies might be. According to Un- schuld [20] Chinese and Japanese philologists are trying Figure 4. Xu li. to find a sense for the phrase xu li, a subject which is still under discussion and, although the author does not want to force a meaning ascribing it to the Greek chyl oi, is close to a possible parallelism between this Chinese de- scription of xu li and the circulation of lymph, include- ing the thoracic duct. The route of the small intestine meridian and the sto- mach in Chinese anatomy can explain why the author considers that the xu li stomach vessel is related to the chyliferous vessels and the thoracic duct: is known that the thoracic duct comes directly from the small intestine (Pecquet’s cistern) Loaded with lymph, it empties itself into the right auricule which is no other that the dilate- tion of the left subclavian vein which together with the left internal jugular forms the vena cava superior. The small intestine empties its processed content directly into the right heart which sends it to the lung and from there to the left heart and general circulation (Chinese Medi- cine states that the heart commands the blood that nour- ishes all the organs) It should not be forgotten that blood in Chinese language involves all the nutritious liquids, among which the lymph stands out. For more interior- ganic relations, let us say that point Bladder 22 in the lumbar region, point to treat the san jiao pathology, is located between the L1 and L2 vertebrae where, from the inside, Pecquet’s cistern rests. The meridian system is clearly conceived as a network linking the functions of all the organic structures. There have been attempts to relate the thoracic duct with the meridian rem mai as mentioned by Maspero [21] in a text where he identifies the ren “vena” with the thoracic lymphatic channel. Me- ridians, although they were conceived by the Chinese as invisible energetic routes, do not represent the author’s idea of the thoracic duct as an actual organ. 3.1. Anatomy of the Intestinal Blood Circulation It may be useful to know the description that Chinese Medicine doctors did of both intestines. They differenti- ated with certainty the small intestine from the large one, and they also analyzed the vascular patterns that nour- ished both of them to deduce their respective functions. Let us remember that one way to interpret the meridians is to assimilate them to the routes of vessels and/or ner- ves. The small intestine starts, according to Chinese Medi- cine, in, gate of darkness (幽 门 you men) pyloric re- gion which comprises the duodenum and the jejunum (Figure 5). The large intestine, which they called wide, shared the ileum with the small bowel as far as the, gate of interception region (阑 门 lan men) ileocecal valve that in other texts [22] is cited as 关 门 guan men, name of the point Stomach 22 on both sides of the ven- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. CM  E. PELUFFO 196 tral midline, 2 cun above and out of the navel and serves to treat low digestive disorders. Ling Shu 31 [23] de- scribes its Anatomy: “The small intestine rests from the back on the ver- tebral column, on the left it twists and makes 16 loops in superposed layers, approaching the large intestine and turning backwards, it rests on th e navel”. The navel ventrally corresponds to the second lumbar vertebrae, where adheres to and fixes the mesentery that holds the Pecquet’s cistern [24]. Large intestine includes the left half of the transverse, the descending colon, the sigmoid, the rectum, and anus from western nomenclature. This apparently strange divi- sion of the intestine comes from the way of distributing the circulation that irrigates this part of the digestive tract The author would like to re-state the fact that the itiner- ary of both blood and energy (meridians) depended on vascular routes, and in this particular case jejunum, il- eum, caecum and transverse colon united because they were supplied by the superior mesenteric artery whereas the Chinese “wide” intestine would get blood from colla- terals to the inferior mesenteric artery. This description would point to the practice of dissections. Each intestine had a different task: the small intestine would rule the digestion process because it absorbed nutrients and digestive juices and, since the wide bowel only absorbed water, it was considered that it would con- trol not exactly the quality but rather the quantity of the organic liquids. Figure 5. Small intestine and “Wide” intestine [25]. 3.2. Meridians The paths of the meridians, another way of explaining the Anatomy in China, express relationships among vis- cera. The internal path of the meridian of the heart from its origins in the middle of the heart (literally in the cen- tre of the heart) but not penetrating it, rather lies on the “heart support”―the pericardium xin bao luo, probably the aorta and some other large vessels going in and out of the heart and along with them crosses through the dia- phragm, passes to the mesenteric artery and branches out in the small intestine which is spirally enveloped by it. Another branch coming out of the heart too outlines the sides of the oesophagus and ascends up to the eye (“to the support of the eye”) probably the optic nerve where it connects with the peripheral tissues of the eyeball and continues to the brain. The external path: the meridian itself leads off from the heart, goes through the lung and into the axilla in whose pit lies jiquan the first point H1. It goes along the arm through the palmar surface radial side next to the meridian xin bao luo on some paths that coincide with the angina pectoris clinics. The ideograph for heart (心 xin) is said to show the heart body: above the aorta, in the middle the viscera and to the sides a synthesis of the pericardium. In Chinese Medicine the heart is principal: “it is the chief of the five zang and the six fu and therein lies Shen the spirit”. The Classics explain that “if the heart is attacked, the Shen go and if the Shen go, then it is death”, “the heart is the trunk where life gets rooted”, “all the blood depends on the heart” [26]. Its functioning is expressed in the mouth, at the tip of the tongue, in the speech. The pre-eminence of the heart is due to the fact that it is the residence of mental energy (神 shen). By the way, let us say that this concept is not strange to the West where for the hermetic medicine practiced by Paracelsus [27] among others, mind is located at the highest part of the right auricle. Meridians are a speculative product of Chinese thought in its application to both body and Medicine. Nanjing 35 [28] already explains that the small intestine as a highly vas- cularised organ (see histological illustration) is the red intestine (movement fire) the large bowel is white intes- tine (metal) the gall bladder is the green intestine (wood) stomach is the yellow intestine (earth) and the bladder the black one (water). The external path of the small intestine meridian – en- ergetically yang starts at the little finger external ungual angle, continues along the cubital side of the hand, as- cends by the posterior external side of the arm, then by the posterior axillary fold, after that it goes to the supra- clavicular pit and enters the thorax to interact with the heart, descends along the oesophagus, crosses the dia- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. CM  197 E. PELUFFO phragm, reaches the stomach and finally the small intes- tine. A branch leaves the small intestine to join the sto- mach at the S39 point. The picture (Figure 3) clearly shows how the SI meri- dian enters the supraclavicular pit, moves towards the thorax to spirally envelope the heart as well as the oe- sophagus and the stomach where it comes in contact with the intragastric material, beginning of the quil that will transport the above mentioned xu li, the stomach luo large vessel. Nanjing 35 shows in a detailed way that the small in- testine has a dynamic relation with the RM 9 point, ren- mai 9 shui fen water partition or water separation point which located on the midline of the abdomen slightly above the navel, regulates the abdominal vasomotricity and is also related to ren mai 10 xia wan “the place of the small intestine” [29]. The small intestine receives water and food from the stomach and during digestion proceeds to separate clear from turbid. The clear are the interstitial liquids, the turbid are the dregs that will move to the large bowel to be evacuated. It is understood what turbid is, and the clear points towards the bowel absorp- tion that will transport the noble materials from the lim- phosanguineum circuit once they have been passed th- rough the liver. Classic texts are precise in their description “The small intestine is responsible for receiving and filling up, and the transformed goes out”. Sheng filling up (剩) refers to an intense physiological activity taking place in the contact surfaces of the bowel villus. The product of this is the transfer of the material so processed to the blood and lymph circulation and to the large intestine as well. For ancient texts the motility of the small bowel “mixes and transports”, that is what we call peristaltism. To make reference to the separation between clear and turbid they use the terms press and sift [30]. There are more data to help understand the relation- ship heart-small intestine. Let us remember that in em- bryology heart and small intestine are formed in the same movement between the 3rd and 4th weeks when the pri- mitive bowel is defined and both cardiac tubes [31] join together. The jejuno-ileon is the result of the anterior portion of the primitive intestine [32]. 4. Conclusions There are Eastern and Western anatomical reasons as well as energetic ones from Chinese Medicine which explain the forming of the heart-small intestine pair. This anatomo-functional approach describes the ab- stract speculative aspects as well as the concrete ones, generally Taoist in origin, on which Chinese Medicine bases its conception of the human body as well as its in- ter relationships. Western culture reasons in a different way, and does not take part in an integrative conception of the body, rather it fractions the human body in appa- ratus with scarce mutual functional connectivity. How- ever, researching and trying to bring together these two conceptions, Western Anatomy has available data to complement the explanation of the Eastern idea. Chinese theoretical-practical notions are the product of a fine and thorough clinical and anatomical observation interested in justifying the integration of organ-function zang 脏 with organ-function fu 腑 at every energy state according to the yin yang principle and qi dynam- ics, which proves the morphophysiologycal interadjust- ment between the naturalistic theoretical conception of the body according to secular Chinese Medicine. 5. References [1] Nanjing, “Versión J. García, 69 Function and Energetics of the Heart in Chinese Medicine,” JGEdiciones, Madrid, 2003. [2] R. González and Y. Jianhua, “Medicina Tradicional China,” Grijalbo, México, 1996 . [3] C. Larre and E. R. de la Vallée, “The Secret Treatise of the Spitirual Orchid,” Monkey Press, London, 2003. [4] L. X. Huang, “An Illustrated Book on the Historical De- velopment of Chinese Acupuncture,” XinTao, Shangdong, 2003. [5] “Diccionario Español de la Lengua China,” Madrid, 1977. [6] S. Ling, versión de J. García. JGEdiciones, Madrid, 2002. [7] D. Sussmann, Acupuntura Teoría y Práctica, Ed., Kier Buenos Aires, 1968. [8] J. Lavier, “Histoire, Doctrine et Pratique de l’Acupuncture Chinoise,” Tchou Éditeur, Genève, 1966. [9] B. Flaws, “The Classic of Difficulties,” Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO 2004: 57 Anatomy and Physiology of Heart-Small Intestine Pair. [10] Imagen de Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad de Chile. [11] M. Porkert, “The Theoretical Foundations of Chinese Medicine,” The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1974. [12] N. Sivin, “Traditional Medicine in Contemporary China,” Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. [13] R. E. Siegel, “Galen´s System of Physiology and Medi- cine S-Karger,” Basel, 1968. [14] C. Singer, “A Short History of Anatomy from Greeks to Harvey,” Dover Publications Inc., New York, 1957. [15] W. Sodeman, Jr. and W. Sodeman, “Fisiopatología Clínica,” Interamericana, México, 1978. [16] W. Su, “Preguntas Sencillas, Traducción de J.García,” JGE ediciones, 2005. [17] J. Schatz, C. Larre and E. Rochat, “Aperçus de Médecine Copyright © 2011 SciRes. CM  E. PELUFFO 198 Traditionnelle Chinoise,” Desclée de Brouwer, Paris, 1994. [18] R. González and J. H.Yan, “Medicina Tradicional China,” Grijalbo, México, 1996. [19] “Dictionaire Ricci de Caracteres Chinois,” Instituts Ricci Paris Taipei Desclée de Brouwer, 1999. [20] P. Unschuld, “Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen,” University of California Press, Berkeley, 2003. [21] H. Maspero, “El Taoísmo y las Religiones Chinas,” Trotta, Mafrid, 2000. [22] D. Kendall, “Dao of Chinese Medicine,” Oxford Univer- sity Press, 2002. [23] S. Ling, “(Eje Espiritual) versión de J.García,” JGEdiciones, Madrid, 2002. [24] L. Testut, “Compendio de Anatomía Descriptiva,” Salvat y Cia, Barcelona, 1917. [25] Neijing, “Versión de Ilza Veith,” University of California Press, Berkeley, 1972. [26] E. R. de la Vallée and C. Larre, “Su Wen Les 11 Premiers Traités,” Maisonneuve Institut Ricci, 1993. [27] E. Marié, “Introduction à la Médecine Hermetique à Travers l’Oeuvre de Paracelse,” Éditions Paracelse, Vitré, 1988. [28] Nanjing, “Versión de J.García,”JGE Ediciones, Madrid, 2003. [29] J. Lei and Y. Tu, “Illustrated Wings to the Canon of Cate- gories,” In: K. Matsumoto and S. Birch, Eds., Hara Di- agnosis, Reflections on the the Sea, 55. [30] E. Peluffo, “Apuntes de Medicina China,” Miraguano Ediciones, Madrid, 2003. [31] J. Langman, “Embriología Médica,” Editorial Médica Panamericana, Buenos Aires, 1982. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. CM |