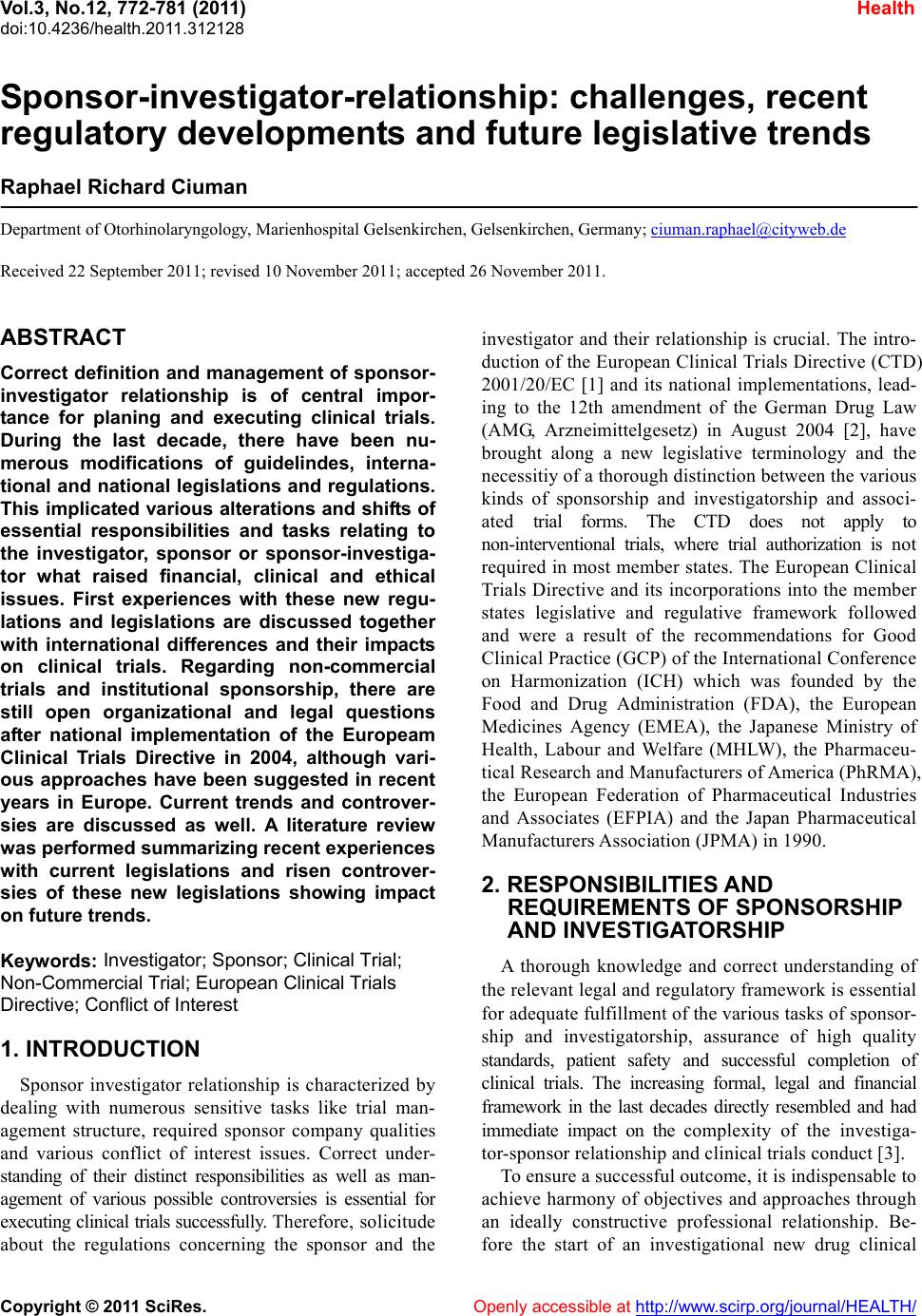

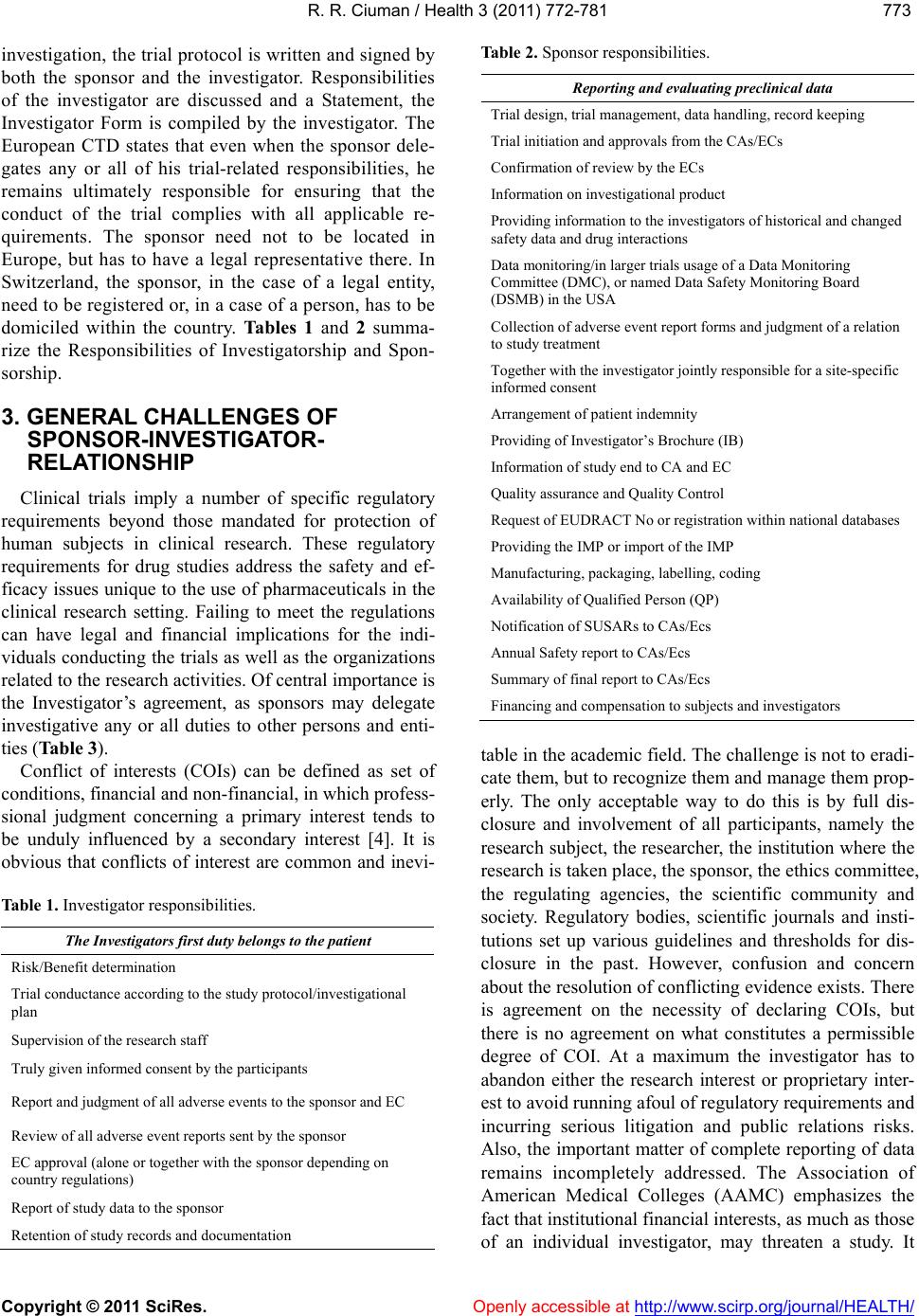

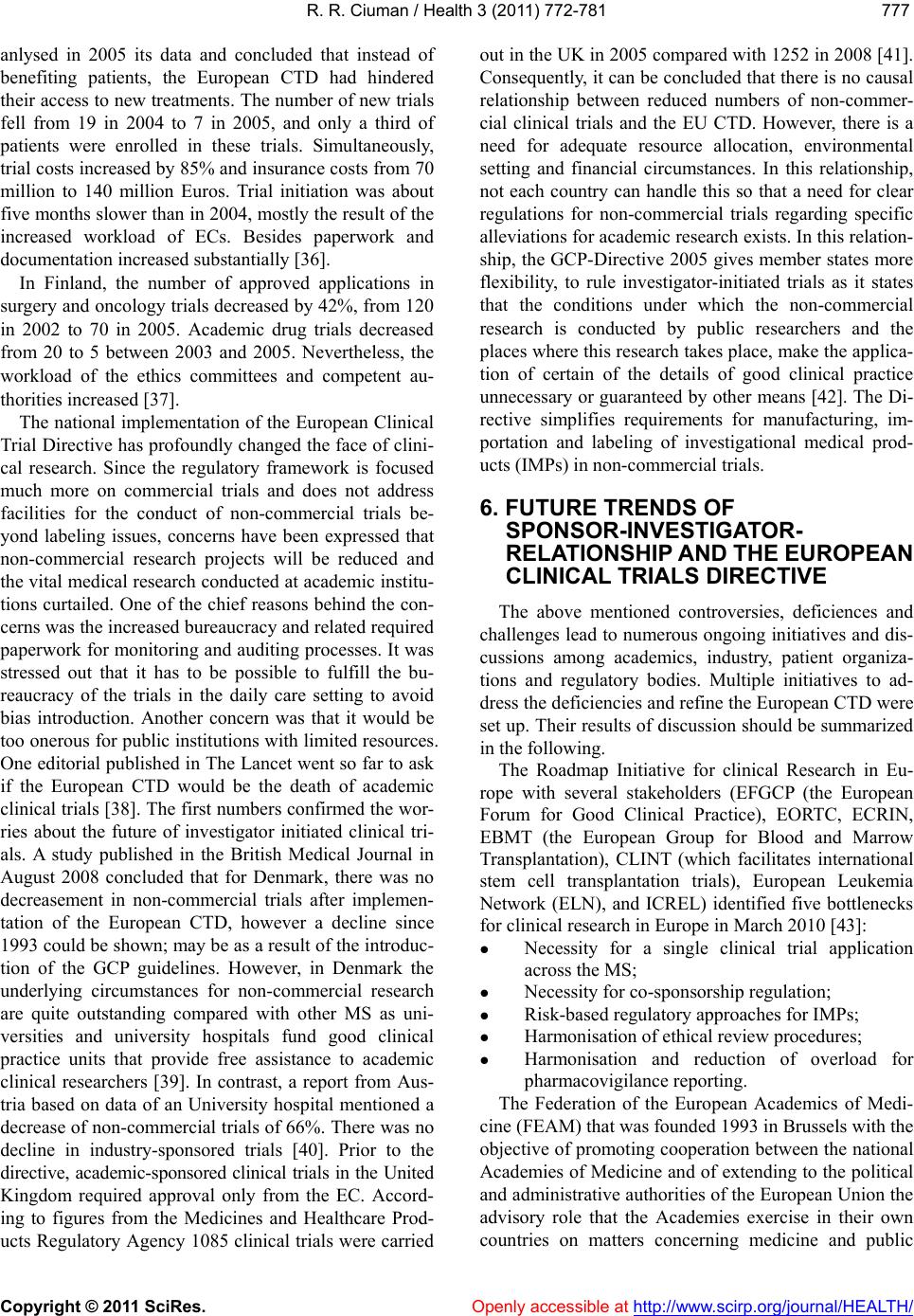

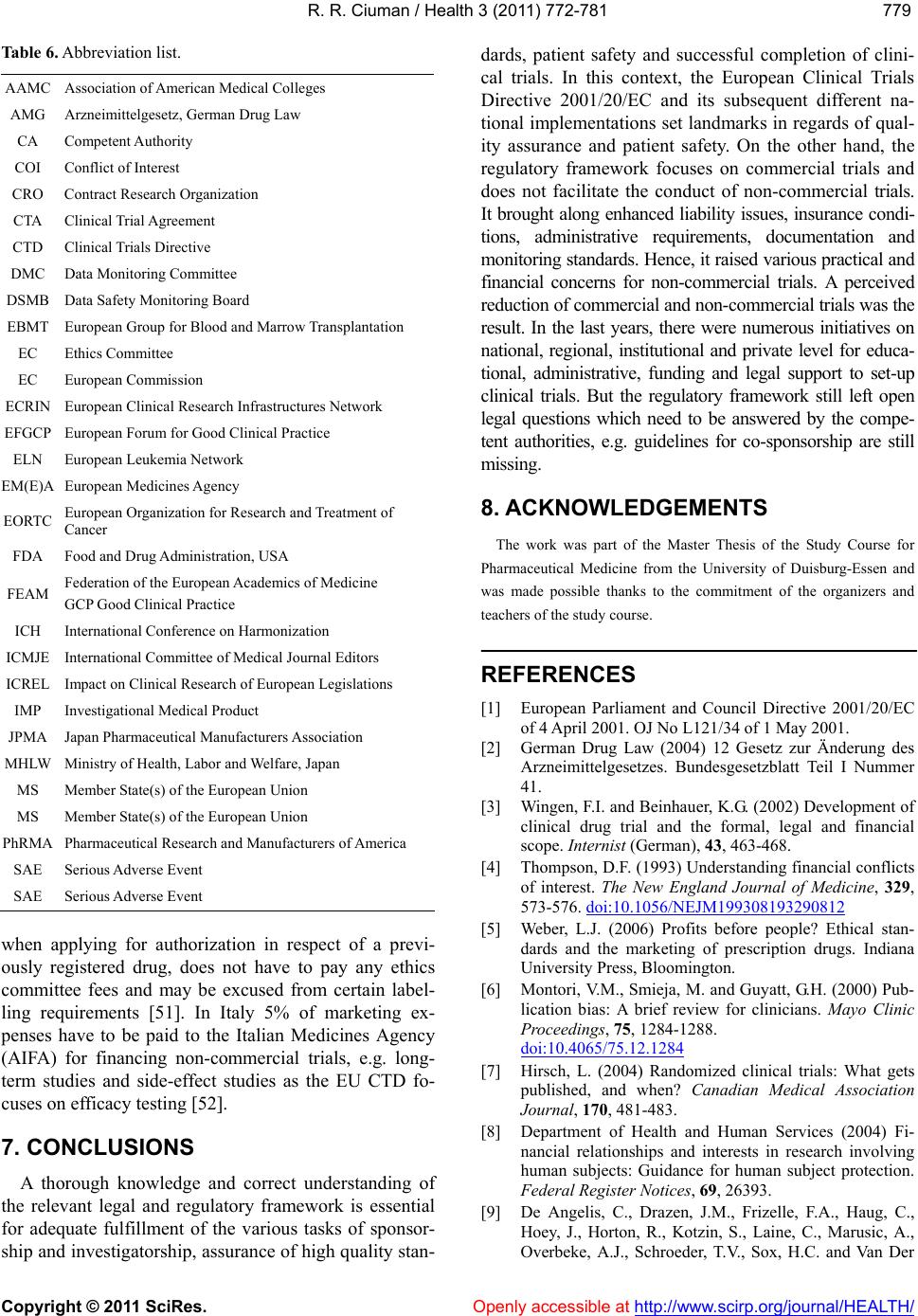

Vol.3, No.12, 772-781 (2011) doi:10.4236/health.2011.312128 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Sponsor-investigator-relationship: challenges, recent regulatory developments and future legislative trends Raphael Richard Ciuman Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Marienhospital Gelsenkirchen, Gelsenkirchen, Germany; ciuman.raphael@cityweb.de Received 22 September 2011; revised 10 November 2011; accepted 26 November 2011. ABSTRACT Correct definition and management of sponsor- investigator relationship is of central impor- tance for planing and executing clinical trials. During the last decade, there have been nu- merous modifications of guidelindes, interna- tional and national legislations and regulations. This implicated various alterations and shifts of essential responsibilities and tasks relating to the investigator, sponsor or sponsor-investiga- tor what raised financial, clinical and ethical issues. First experiences with these new regu- lations and legislations are discussed together with international differences and their impacts on clinical trials. Regarding non-commercial trials and institutional sponsorship, there are still open organizational and legal questions after national implementation of the Europeam Clinical Trials Directive in 2004, although vari- ous approaches have been suggested in recent years in Europe. Current trends and controver- sies are discussed as well. A literature review was performed summarizing recent experiences with current legislations and risen controver- sies of these new legislations showing impact on future trends. Keywords: Investigator; Sponsor; Clinical Trial; Non-Commercial Trial; European Clini ca l Trials Directive; Conflict of Interest 1. INTRODUCTION Sponsor investigator relationship is characterized by dealing with numerous sensitive tasks like trial man- agement structure, required sponsor company qualities and various conflict of interest issues. Correct under- standing of their distinct responsibilities as well as man- agement of various possible controversies is essential for executing clinical trials successfully. Therefore, solicitude about the regulations concerning the sponsor and the investigator and their relationship is crucial. The intro- duction of the European Clinical Trials Directive (CTD) 2001/20/EC [1] and its national implementations, lead- ing to the 12th amendment of the German Drug Law (AMG, Arzneimittelgesetz) in August 2004 [2], have brought along a new legislative terminology and the necessitiy of a thorough distinction between the various kinds of sponsorship and investigatorship and associ- ated trial forms. The CTD does not apply to non-interventional trials, where trial authorization is not required in most member states. The European Clinical Trials Directive and its incorporations into the member states legislative and regulative framework followed and were a result of the recommendations for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) which was founded by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMEA), the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), the Pharmaceu- tical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associates (EFPIA) and the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA) in 1990. 2. RESPONSIBILITIES AND REQUIREMENTS OF SPONSORSHIP AND INVESTIGATORSHIP A thorough knowledge and correct understanding of the relevant legal and regulatory framework is essential for adequate fulfillment of the various tasks of sponsor- ship and investigatorship, assurance of high quality standards, patient safety and successful completion of clinical trials. The increasing formal, legal and financial framework in the last decades directly resembled and had immediate impact on the complexity of the investiga- tor-sponsor relationship and clinical trials conduct [3]. To ensure a successful outcome, it is indispensable to achieve harmony of objectives and approaches through an ideally constructive professional relationship. Be- fore the start of an investigational new drug clinical  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http:// www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 773773 investigation, the trial protocol is written and signed by both the sponsor and the investigator. Responsibilities of the investigator are discussed and a Statement, the Investigator Form is compiled by the investigator. The European CTD states that even when the sponsor dele- gates any or all of his trial-related responsibilities, he remains ultimately responsible for ensuring that the conduct of the trial complies with all applicable re- quirements. The sponsor need not to be located in Europe, but has to have a legal representative there. In Switzerland, the sponsor, in the case of a legal entity, need to be registered or, in a case of a person, has to be domiciled within the country. Ta ble s 1 and 2 summa- rize the Responsibilities of Investigatorship and Spon- sorship. 3. GENERAL CHALLENGES OF SPONSOR-INVESTIGATOR- RELATIONSHIP Clinical trials imply a number of specific regulatory requirements beyond those mandated for protection of human subjects in clinical research. These regulatory requirements for drug studies address the safety and ef- ficacy issues unique to the use of pharmaceuticals in the clinical research setting. Failing to meet the regulations can have legal and financial implications for the indi- viduals conducting the trials as well as the organizations related to the research activities. Of central importance is the Investigator’s agreement, as sponsors may delegate investigative any or all duties to other persons and enti- ties (Table 3). Conflict of interests (COIs) can be defined as set of conditions, financial and non-financial, in which profess- sional judgment concerning a primary interest tends to be unduly influenced by a secondary interest [4]. It is obvious that conflicts of interest are common and inevi- Table 1. Investigator responsibilities. The Investigators first duty belongs to the patient Risk/Benefit determination Trial conductance according to the study protocol/investigational plan Supervision of the research staff Truly given informed consent by the participants Report and judgment of all adverse events to the sponsor and EC r together with the sponsor depending on Retention of study records and documentation Review of all adverse event reports sent by the sponsor EC approval (alone o country regulations) Report of study data to the sponsor Table 2. Sponsor responsibilities. Reporting and evaluating preclinical data Trial design, trial management, data handling, record keeping Trial initiation and approvals from the CAs/ECs Confirmation of review by the ECs Information on investigational product Providing information to the investigators of historical and changed safety data and drug interactions Data monitoring/in larger trials usage of a Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), or named Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) in the USA Collection of adverse event report forms and judgment of a relation to study treatment Together with the investigator jointly responsible for a site-specific informed consent Arrangement of patient indemnity Providing of Investigator’s Brochure (IB) Information of study end to CA and EC Quality assurance and Quality Control Request of EUDRACT No or registration within national databases Providing the IMP or import of the IMP Manufacturing, packaging, labelling, coding Availability of Qualified Person (QP) Notification of SUSARs to CAs/Ecs Annual Safety report to CAs/Ecs Summary of final report to CAs/Ecs Financing and compensation to subjects and investigators table in the academic field. The challenge is not to eradi- cate them, but to recognize them and manage them prop- erly. The only acceptable way to do this is by full dis- closure and involvement of all participants, namely the research subject, the researcher, the institution where the research is taken place, the sponsor, the ethics committee, the regulating agencies, the scientific community and society. Regulatory bodies, scientific journals and insti- tutions set up various guidelines and thresholds for dis- closure in the past. However, confusion and concern about the resolution of conflicting evidence exists. There is agreement on the necessity of declaring COIs, but there is no agreement on what constitutes a permissible degree of COI. At a maximum the investigator has to abandon either the research interest or proprietary inter- est to avoid running afoul of regulatory requirements and incurring serious litigation and public relations risks. Also, the important matter of complete reporting of data remains incompletely addressed. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) emphasizes the fact that institutional financial interests, as much as those of an individual investigator, may threaten a study. It  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http:// www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 774 Table 3. Challenges of sponsor-investigator-relationship. General challenges Variabile responsibility in different countries of trial approval and notification to the CAs/Ecs National differences in timelines of applications, adverse event reporting, data storing Clear communication and input channels Risk/Benefit determination Structural and educational support for trial set-up Conflict of interest Challenges to consider in the investigator’s agreement Regulatory compliance Confidentiality Termination rights Data monitoring and data analysis Intellectual property and patent rights Publication Subject injury Insurance Indemnification and liability Payments Third-party reimbursements goes well beyond the requirement for full financial dis- closure of investigators and recommend that individuals who hold a financial interest in a particular area of re- search should not be involved in clinical research in that area [5]. Criteria for data ownership and access, data design, collection and analysis (including outside analysis) are common claims a long time to adequately manage the reasons for publication bias [6], which clearly extends to non-commercial research [7]. Besides, data ownership issues start to play a distinctive role inside definitions of non-commercial sponsors. In the US, the Department of Health and Human Services recommends that responsi- bilities involving design of the study and analysis of the results should be shared between a sponsor and investi- gators in order to prevent potential influence of financial relationships on the outcome of the trial [8]. The Inter- national Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) has set guidelines of sponsored research regarding au- thors’ access to data, integrity of data, accuracy of data analysis, authors publishing rights and trial registration in a data base to qualify for publication [9]. The majority of quality general medicinal journals require disclosure of the role of the sponsor and a written assurance that the investigators accept full responsibility for the conduct of the study, have had access to all the data and had the authority to publish it. In addition, these guidelines re- quire editors to verify (if necessary, by inspecting re- search contracts and study protocols) that researchers had full access to all study data and that there were no restrictions on publication [10]. Concerns about bias, research fraud and the ethics of clinical trials can be addressed by truly independent and properly constituted data and safety monitoring boards (DSMBs). The DSMB is an independent group of clini- cians and statisticians and meets periodically to review the unblinded data that the sponsor has received so far. The DMSB has the power to recommend termination of the study based on their review, for example if the study treatment is causing more deaths than the standard treat- ment, or seems to be causing unexpected and study-re- lated serious adverse events. Truly independent and properly constituted data and safety monitoring boards are of particular importance when academic investiga- tors or universities have a large financial conflict. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) requires a Data Sa- fety Monitoring Board (DSMB) for all Phase III trials and a safety monitoring plan for Phase I and II trials. The FDA issued in 2006 guidance for clinical trial spon- sors for the establishment and operation of clinical trials monitoring committees [11]. The FDA requires a DSMB for long-term trials with mortality or major morbidity outcome measures, when serious adverse events (SAE) are expected, with novel and/or potentially high-risk treatments, when very little prior information about the study treatment is available, when studying an at-risk population consisting of vulnerable subjects (e.g., eld- erly or paediatric patients) or with a multicenter or long- term study. Conversely, an external DSMB is not re- quired in early phase trials (with the exemption of gene therapy trials), trials with symptom-only endpoints, and short-term trials. In the last decade, numerous studies addressed the problems of selective data presentation [12-14], data suppression, named authorship and that industry-spon- sored trials report less often negative outcomes than in- dependent studies. Positive and significant results are more often published than negative and insignificant results [15-17] and in the past only 25% - 50% of ap- proval studies were published according to comparisons with FDA data [18]. Consequently, there have been nu- merous calls for publicly available study protocols and results, as industrial financing tends to affect study pro- cedures, results and publication in multiple ways which cannot be explained by methodological study quality [19, 20]. In this context, the new trial databases and the ini- tiatives of publishers of medical journals addressed and tried to set guidelines to ensure high-standard publica- tion. In contrast to Europe, in the USA all clinical trials have to be registered in a database with free public ac-  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http:// www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 775775 cess. In Europe this is not legally enforced but due to an initiative. In addition, in the USA study publication be- came mandatory in 2008 [21,22]. The passage of Title VIII (Section 801) of the FDA Amendment Act (FDAAA) of 2007, made it federal law to register most intervene- tional clinical trials at outset and to disclose trial results (for marketed products) by twelve months after study completion [23,24]. There exists general agreement by the industry to make clinical trial results public [25]. Besides PhRMA recently extended its policy to go be- yond the current FDAAA requirements, calling on its members to register and disclose results of all studies involving patients for all products marketed and those investigational products whose development has been discontinued [26]. Due to increased regulation and legislation in the last decades bringing along higher research costs and slower patient recruitment, many research-based companies seek to outsource some of their trials to Third World countries with less stringent regulation like China, India, Indonesia or Thailand. Nevertheless, the laws and regu- lations might differ in substantial manner. Sponsors and investigators must deal with multiple legal jurisdictions, with different laws regulations and other rules and has to understand regional differences. Consequently, the spon- sor often needs to fall back on local resources and con- tract research organizations (CROs). In India for example, which is a particularly attractive site for clinical research due to its genetically diverse population, sponsors do not have exclusive rights to the clinical data they generate, as trial reports are in the public domain. Consequently, manufacturers of generic drugs can use the data to get regulatory approval for their own versions of drugs. China has a long regulatory clinical trial approval proc- ess, which may take up to one year, minimum 195 days to review an application for a multinational study [27]. Intellectual property rights are only sporadic enforced. In contrast, Latin American countries like Argentina, Brazil and Mexico generally comply with ICH guidelines. Vio- lation of Western standards might be the ground for li- ability claims in Western and Third World countries in a jointly manner. The Abdullahi vs. Pfizer Case underlines the need to ensure that a company conducting clinical trials in Third World Countries keeps regulatory and ethical requirements. In this case an US sponsor who conducted a clinical trial in Nigeria was sued under the Alien Tort Statue [28], which allows United States courts to hear human rights cases brought by foreign citizens for conduct com- mitted outside the United States. 4. CHALLENGES OF THE EUROPEAN CLINICAL TRIALS DIRECTIVE The goals of the CTD 2001/20/EC were primarily en- forcement of patient protection, enhanced drug quality standards for clinical trials and enhanced transparency. These goals were obviously met. In this context, the Eu- ropean Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC and its sub- sequent different national implementations set land- marks in regards of quality assurance and patient safety, as a GCP-inspection system and trial amendment and termination provisions were established. On the other hand the challenges and deficiencies of this framework are wide-ranging as summarized in Table 4. Challenges and Deficiences of the European Clinical Trials Direc- tive 2001/20/EC and its national implementations. The most challenging of the European CTD is the concept of the sponsor. Originally, the CTD defined a sponsor as an individual, company, institution or organi- sation which takes responsibility for the initiation, man- agement and/or financing of a clinical trial. In contrast, the European Commsson stated in its Notice to Appli- cants in 2009 that a number of parties may agree in writ- ing to form organisation and to distribute the sponsors tasks and duties between various sponsors and organisa- tions [29]. UK legislation with its Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004 maintained its provisions for multiple and shared sponsorship, defined Ta b l e 4 . Challenges and Deficiences of the European Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC and its national implementations. Deficiences and Challenges of the European Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC No addressment of multiple, joint or co-sponsorship No addressment of non-commercial sponsorship and facilities beyond labelling No risk assessment classification for graded clinical trial applications Lack of addressment of facilities for informed consent in disabled populations or emergency cases No definition of substantial amendments; No grouping possibility for amendments No substantive liability rules EudraCT is not publicly available and does not include non-commercial trials/no public available database for study protocols and results Increased costs due to increased authorization, monitoring and documentation requirements/increased need for managing competencies SAE reporting to ECs and distribution to all investigators regardless of causality provides information overload and information of little value Challenges of national implementations Definition of IMP and related provisions vary across the MS Differences in timelines and regulations for clinical trial approval, adverse event reporting, study record retention Differences of insurance policies and liability issues across the MS Lack of EU-wide insurance for multinational trials  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http:// www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 776 as follows: single sponsorship—one organization accepts all sponsor’s responsibilities; joint sponsorship―two or more organizations act jointly to accept all of the sponsor’s responsibilities; co-sponsorship―two or more organizations take ultimate responsibility for discrete sponsor respon- sibilities; e.g. one organisation is responsible for GCP and conduct the other for pharmacovigilance and the third for authorisation and EC opinion [30]. The implementation of the European CTD into na- tional law lead to various regulatory differences in the EU member states (MS). Significant differences exist in insurance coverage and liability issues throughout Eu- rope. Patients are EU-wide covered by the trial insurance, but differences remained in place regarding the amounts (total and individual per trial) specified by each MS. Due to its complicated nature it is obvious that different countries handle the compensation to the injured re- search patient differently, including the extent and dura- tion of coverage and the assignment of responsibility for paying compensation, the kind of compensable injuries including death, serious harm pain suffering and eco- nomic losses, the compensability of harms and of health problems which are inevitable in a trial. The nature of the insurance is optional according to US federal regula- tions and compulsory in Europe [31]. Different interpret- tations of the European CTD lead to various regulatory differences in the MS making multinational trials more difficult. The timelines for Competent Authority (CA) or Ethics Committee (EC) approval, adverse event report- ing or retention of study records differ in the MS. In Spain and France missing response by the CA means approval. Information of any urgent safety measure to the CA or EC is required in Germany and Belgium im- mediately, in England within three days. Most MS re- quire immediate reporting of Suspected Unexpected Se- rious Adverse Reactions (SUSARs). In France a declara- tion SUSARs to the the CA and EC is required every six months. In France, UK and Sweden it is possible to ap- peal against negative EC decision. Besides, Germany and Italy have not established a national ethics review committee. Both countries continue to have regional ethics boards. Researchers must apply to each local ju- risdiction where a proposed trial takes place. The European CTD does not address procedures in patients who are unable to give informed consent. Re- search in populations with difficulties to get informed consent, e.g. emergency medicine psychiatry, neurology, has been impacted due to variable and often restrictive consenting procedures for incapacitated subjects, with some countries requiring a court-appointed representa- tive, while others recognise consent from family mem- bers and occasionally professional representatives [32]. In this context, regulations for strict risk/benefit analysis, involvement of ECs, relatives and request procedures for informed consent subsequently are necessary. 5. FIRST EXPERIENCES WITH THE EUROPEAN CLINICAL TRIALS DIRECTIVE So far, there is no simplification or acceleration of administrative processes contrasting the goal of facilitat- ing faster access to novel therapies through harmoniza- tion of administrative regulatory requirements and de- fining binding timelines for the review and approval processes. Concern of delays of 4 to 11 months before trial initiation of cancer studies were expressed [33]. Since the implementation of the ICH-GCP, sponsors are not only responsible for initiation but also for the management of clinical trials. It was reported that the initial response for clinical trials to the implementation of the ICH-GCP guideline were clinical trial price in- creases and a decrease in the number of study contracts [34]. Similar developments were assumed and feared for the implementations of the European CTD. Because reg- isters and statistics about clinical trials were not rou- tinely maintained in the past, every estimation on the quantitative impact of the CTD 2001/20/EC on the number of trials remains rudimentary. A perceived re- duction of commercial and non-commercial trials was described by numerous authors. The consortium of European Forum for Good Clinical Practice (EFGCP) that is comprised by the European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN), the European Organi- zation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna and Hospital Clinic I de Barcelona established the pro- ject Impact on Clinical research of European Legislation (ICREL), a one year project to analyze the impact of the CTD on on the number, size and nature of clinical trials, on workload, required resources, costs and performance of European clinical research. An online survey was launched in May 2008. In 2008 ICREL stated a slight decrease in commercial trials [35]. Further results were summarized as follows: performing clinical trials has become considerably more difficult and costly; each year about 21,000 substantial amendments are notified to the national competent authorities; each national competent authority gets approxi- mately 5700 SUSAR reports per year, a 6-fold in- crease compared to 2003 (multi-reporting, over- reporting). Contrastingly to the ICREL results EORTC, the larg- est independent cancer research network in Europe,  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http:// www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 777777 anlysed in 2005 its data and concluded that instead of benefiting patients, the European CTD had hindered their access to new treatments. The number of new trials fell from 19 in 2004 to 7 in 2005, and only a third of patients were enrolled in these trials. Simultaneously, trial costs increased by 85% and insurance costs from 70 million to 140 million Euros. Trial initiation was about five months slower than in 2004, mostly the result of the increased workload of ECs. Besides paperwork and documentation increased substantially [36]. In Finland, the number of approved applications in surgery and oncology trials decreased by 42%, from 120 in 2002 to 70 in 2005. Academic drug trials decreased from 20 to 5 between 2003 and 2005. Nevertheless, the workload of the ethics committees and competent au- thorities increased [37]. The national implementation of the European Clinical Trial Directive has profoundly changed the face of clini- cal research. Since the regulatory framework is focused much more on commercial trials and does not address facilities for the conduct of non-commercial trials be- yond labeling issues, concerns have been expressed that non-commercial research projects will be reduced and the vital medical research conducted at academic institu- tions curtailed. One of the chief reasons behind the con- cerns was the increased bureaucracy and related required paperwork for monitoring and auditing processes. It was stressed out that it has to be possible to fulfill the bu- reaucracy of the trials in the daily care setting to avoid bias introduction. Another concern was that it would be too onerous for public institutions with limited resources. One editorial published in The Lancet went so far to ask if the European CTD would be the death of academic clinical trials [38]. The first numbers confirmed the wor- ries about the future of investigator initiated clinical tri- als. A study published in the British Medical Journal in August 2008 concluded that for Denmark, there was no decreasement in non-commercial trials after implemen- tation of the European CTD, however a decline since 1993 could be shown; may be as a result of the introduc- tion of the GCP guidelines. However, in Denmark the underlying circumstances for non-commercial research are quite outstanding compared with other MS as uni- versities and university hospitals fund good clinical practice units that provide free assistance to academic clinical researchers [39]. In contrast, a report from Aus- tria based on data of an University hospital mentioned a decrease of non-commercial trials of 66%. There was no decline in industry-sponsored trials [40]. Prior to the directive, academic-sponsored clinical trials in the United Kingdom required approval only from the EC. Accord- ing to figures from the Medicines and Healthcare Prod- ucts Regulatory Agency 1085 clinical trials were carried out in the UK in 2005 compared with 1252 in 2008 [41]. Consequently, it can be concluded that there is no causal relationship between reduced numbers of non-commer- cial clinical trials and the EU CTD. However, there is a need for adequate resource allocation, environmental setting and financial circumstances. In this relationship, not each country can handle this so that a need for clear regulations for non-commercial trials regarding specific alleviations for academic research exists. In this relation- ship, the GCP-Directive 2005 gives member states more flexibility, to rule investigator-initiated trials as it states that the conditions under which the non-commercial research is conducted by public researchers and the places where this research takes place, make the applica- tion of certain of the details of good clinical practice unnecessary or guaranteed by other means [42]. The Di- rective simplifies requirements for manufacturing, im- portation and labeling of investigational medical prod- ucts (IMPs) in non-commercial trials. 6. FUTURE TRENDS OF SPONSOR-INVESTIGATOR- RELATIONSHIP AND THE EUROPEAN CLINICAL TRIALS DIRECTIVE The above mentioned controversies, deficiences and challenges lead to numerous ongoing initiatives and dis- cussions among academics, industry, patient organiza- tions and regulatory bodies. Multiple initiatives to ad- dress the deficiencies and refine the European CTD were set up. Their results of discussion should be summarized in the following. The Roadmap Initiative for clinical Research in Eu- rope with several stakeholders (EFGCP (the European Forum for Good Clinical Practice), EORTC, ECRIN, EBMT (the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation), CLINT (which facilitates international stem cell transplantation trials), European Leukemia Network (ELN), and ICREL) identified five bottlenecks for clinical research in Europe in March 2010 [43]: Necessity for a single clinical trial application across the MS; Necessity for co-sponsorship regulation; Risk-based regulatory approaches for IMPs; Harmonisation of ethical review procedures; Harmonisation and reduction of overload for pharmacovigilance reporting. The Federation of the European Academics of Medi- cine (FEAM) that was founded 1993 in Brussels with the objective of promoting cooperation between the national Academies of Medicine and of extending to the political and administrative authorities of the European Union the advisory role that the Academies exercise in their own countries on matters concerning medicine and public  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http:// www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 778 health summarized their suggestions for further devel- opments of the European regulative framework as fol- lows in August 2010 [44]: Necessity for streamlining assessment of multina- tional studies by the competent authorities and na- tional ethics committees; Necessity for definition of substantial amendments; Necessity for definition of special research populations; Necessity for definition of multiple sponsorship; Development of a consistent risk-based insurance system across Europe; Necessity for a responsible body for SUSARs and avoiding of adverse event reporting to ECs (only annual safety report); Necessities for further strategies for improving the EU clinical research environment and funding. The term non-commercial trial emerged from the Eu- ropean CTD. However, no common definition exists in the EU to explain what a non-commercial trial is. Re- garding non-commercial trials and institutional spon- sorship, there are still open organizational and legal questions, although various approaches have been sug- gested in recent years. The European Forum for Good Clinical Practice (EFGCP) pointed out the necessity to set-up public sponsors for national as well as interna- tional studies in May 2005 [45]. Consequently, in the last years, there were numerous initiatives on national, regional, institutional and private level for educational, administrative, funding and legal support to set-up clinical trials on multiple levels, European, national, institutional and scientific or investigator-driven, as summarized in Ta bl e 5 Initiatives for non-commercial trial support since implementation of the European Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC. As a consequence EU-wide infrastructure networks and disease-oriented scientific networks were set up or existing networks were reinforced to overcome these obstacles [46,47]. Bergmann et al. suggested an expanded role for expert organizations like the EORTC. They could provide a forum for academics and industry to plan within a regulatory framework and work closely with the regu- latory authorities and legislative bodies [48]. EORTC already coordinates multicenter trials. Other authors called for a network of centers of excellence in clinical research in Europe, where clinical trials should be re- ferred to and conducted [49]. Investigator-driven trials often deal with potential di- agnostic and therapeutic innovations that do not attract commercial interests, e.g. proof of concept studies, stud- ies on orphan diseases, comparison of diagnostic or therapeutic interventions, surgical therapies or novel indications for registered drugs. Very few public entities (universities hospitals, funding bodies, charitable or- Ta ble 5. Initiatives for non-commercial trial support since im- plementation of the European Clinical Trials Directive 2001/ 20/EC. Initiatives for non-commercial t r i a l support European Clinical Research Infrastructures Network (ECRIN) founded in 2004 supports investigators and sponsors with consultan- cies (such as information on regulatory and ethical requirements, consulting on centre selection, insurance) and services (such as in- teraction with competent authorities and ethics committees, study monitoring ) to overcome the national legislative differences in mul- tinational trials Regulatory facilitations on national level were set up Coordinating centers for clinical research, the Koordinierungszentren für klinische Studien (KKS) were established at collective centers at several universities by the BMBF in Germany Public-limited companies (Sponsor GmbHs) and private hospital units were set up at hospitals in Germany Networks and disease-oriented scientific networks were set up or ex- isting networks were reinforced, e.g. EORTC, ELN Calls for national or European funding agencies like the NIH Calls for network of centers of excellence in clinical research in Europe, where clinical trials should be referred to and conducted Calls for expanded role for expert organizations like the EORTC which already coordinate multicenter trials, as they could provide a forum for academics and industry to plan within a regulatory frame- work and work closely with the regulatory authorities and legislative bodies Calls for Academic Research Organizations (AROs) allocated at the universities which provide almost all services that are required from a commercial sponsor Calls for clinical trial networks of universities and hospitals similar to the USA which receive with from both industry and NIH ganizations) had the necessary infrastructure to handle the increased administrative and legal requirements. Funding was usually insufficient to pay for the increased administrative costs. In this context, the Guidance docu- ment on specific modalities for non-commercial trials mentions in recital 11 of the 2005/28/EC Directive states that the data from non-commercial trials cannot be used for registration [50], which is a major obstacle to aca- demic-sponsored research and to the development of new indications for marketed medicines, especially in rare diseases. Consequently, it exists a need for further definition and facilitations for non-commercial trials across the MS. A waiver-system for non-commercial trials and a waiver for the sponsor to purchase the IMP in non-commercial trials or harmonizing and providing uniform models for insurance coverage and liability for non-commercial trials by the public health system, by the public hospitals or by the university hospitals might constitute mile stones in this direction. For example, in Belgium the sponsor of a non-commercial trial does not file certain quality data with the government authority  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http:// www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 779779 Table 6. Abbreviation list. AAMC Association of American Medical Colleges AMG Arzneimittelgesetz, German Drug Law CA Competent Authority COI Conflict of Interest CRO Contract Research Organization CTA Clinical Trial Agreement CTD Clinical Trials Directive DMC Data Monitoring Committee DSMB Data Safety Monitoring Board EBMT European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation EC Ethics Committee EC European Commission ECRIN European Clinical Research Infrastructures Network EFGCP European Forum for Good Clinical Practice ELN European Leukemia Network EM(E)A European Medicines Agency EORTC European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer FDA Food and Drug Administration, USA FEAM Federation of the European Academics of Medicine GCP Good Clinical Practice ICH International Conference on Harmonization ICMJE International Committee of Medical Journal Editors ICREL Impact on Clinical Research of European Legislations IMP Investigational Medical Product JPMA Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association MHLW Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan MS Member State(s) of the European Union MS Member State(s) of the European Union PhRMA Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America SAE Serious Adverse Event SAE Serious Adverse Event when applying for authorization in respect of a previ- ously registered drug, does not have to pay any ethics committee fees and may be excused from certain label- ling requirements [51]. In Italy 5% of marketing ex- penses have to be paid to the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) for financing non-commercial trials, e.g. long- term studies and side-effect studies as the EU CTD fo- cuses on efficacy testing [52]. 7. CONCLUSIONS A thorough knowledge and correct understanding of the relevant legal and regulatory framework is essential for adequate fulfillment of the various tasks of sponsor- ship and investigatorship, assurance of high quality stan- dards, patient safety and successful completion of clini- cal trials. In this context, the European Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC and its subsequent different na- tional implementations set landmarks in regards of qual- ity assurance and patient safety. On the other hand, the regulatory framework focuses on commercial trials and does not facilitate the conduct of non-commercial trials. It brought along enhanced liability issues, insurance condi- tions, administrative requirements, documentation and monitoring standards. Hence, it raised various practical and financial concerns for non-commercial trials. A perceived reduction of commercial and non-commercial trials was the result. In the last years, there were numerous initiatives on national, regional, institutional and private level for educa- tional, administrative, funding and legal support to set-up clinical trials. But the regulatory framework still left open legal questions which need to be answered by the compe- tent authorities, e.g. guidelines for co-sponsorship are still missing. 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work was part of the Master Thesis of the Study Course for Pharmaceutical Medicine from the University of Duisburg-Essen and was made possible thanks to the commitment of the organizers and teachers of the study course. REFERENCES [1] European Parliament and Council Directive 2001/20/EC of 4 April 2001. OJ No L121/34 of 1 May 2001. [2] German Drug Law (2004) 12 Gesetz zur Änderung des Arzneimittelgesetzes. Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I Nummer 41. [3] Wingen, F.I. and Beinhauer, K.G. (2002) Development of clinical drug trial and the formal, legal and financial scope. Internist (German), 43, 463-468. [4] Thompson, D.F. (1993) Understanding financial conflicts of interest. The New England Journal of Medicine, 329, 573-576. doi:10.1056/NEJM199308193290812 [5] Weber, L.J. (2006) Profits before people? Ethical stan- dards and the marketing of prescription drugs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. [6] Montori, V.M., Smieja, M. and Guyatt, G.H. (2000) Pub- lication bias: A brief review for clinicians. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 75, 1284-1288. doi:10.4065/75.12.1284 [7] Hirsch, L. (2004) Randomized clinical trials: What gets published, and when? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 170, 481-483. [8] Department of Health and Human Services (2004) Fi- nancial relationships and interests in research involving human subjects: Guidance for human subject protection. Federal Register Notices, 69, 26393. [9] De Angelis, C., Drazen, J.M., Frizelle, F.A., Haug, C., Hoey, J., Horton, R., Kotzin, S., Laine, C., Marusic, A., Overbeke, A.J., Schroeder, T.V., Sox, H.C. and Van Der  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http:// www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 780 Weyden, M.B. (2004) Clinical trial registration: A state- ment from the International Committee of Medical Jour- nal editors. The New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 1250-1251. [10] Davidoff, F., DeAngelis, C.D., Drazen, J.M., Nicholis, M.G., Hoey, J., Hojgaard, L., Horton, R., Kotzin, S., Nylenna, M., Overbeke, A., Sox, H.C., Weyden, M. and Wilkes, M.S. (2001) Sponsorship, authorship and ac- countability. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 165, 786-788. [11] FDA (2006) Guidance for clinical trial sponsors on the establishment and operation of clinical trial data moni- toring committees, 71FR 15421. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/G uidances/ucm127073.pdf [12] Ahmer, S., Haider, I.J., Anderson, D. and Arya, P. (2006) Do pharmaceutical companies selectively report clinical trial data. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 22, 338-346. [13] House of Commons Health Committee (2005) The in- fluence of the pharmaceutical industry. Fourth Report of Session, The Stationary Office Limited, London. [14] Ferner, R. (2005) The influence of big pharma. BMJ, 330, 855-856. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7496.855 [15] Turner, E.H., Matthews, A.M., Linardatos, E., Tell, R.A. and Rosenthal, R. (2008) Selective publication of antide- pressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. The New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 252-260. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa065779 [16] Melander, H., Ahlqvist-Rastad, J., Meijer, G. and Beer- mann, B. (2003) Evidence based medicine-selective re- porting from studies sponsored by pharmaceutical indus- try: Review of studies in new drug applications. BMJ, 326, 1171-1173. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1171 [17] Lee, K., Bachetti, P. and Sim, I. (2008) Publication of clinical trials supporting successful new drug applica- tions: a literature analysis. PLoS Medicine, 5, e191. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050191 [18] Rising, K., Bachetti, P. and Bero, L. (2008) Reporting bias in drug trials submitted to the Food and Drug Ad- ministration: Review of publication and presentation. PLoS Medicine, 5, e217. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050217 [19] Schott, G., Pachl, H., Limbach, U., Gundert-Remy, U., Ludwig, W.D. and Lieb, K. (2010) The financing of drug trials by pharmaceutical companies and its consequences. Part 1: A qualitative, systematic review of the literature on possible influences on the findings, protocols, and quality of drug trials. Deutsches Aerzteblatt International (German), 107, 279-285. [20] Schott, G., Pachl, H., Limbach, U., Gundert-Remy, U., Ludwig, W.D. and Lieb, K. (2010) The financing of drug trials by pharmaceutical companies and its consequences. Part 2: A qualitative, systematic review of the literature on possible influences on authorship, access to trial data, and trial registration and publication. Deutsches Aerzte- blatt International (German), 107, 295-301. [21] Kaiser, J. (2008) Making clinical data widely available. Science, 322, 217-218. doi:10.1126/science.322.5899.217 [22] PloS Medicine Editors (2008) Next stop, don’t block the doors: Opening up access to clinical trials results. PloS Medicine, 5, e160. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050160 [23] US Department of Health and Human Services (2007) Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007, P.L. 110-185. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/F ederalFoodDrugandCosmeti- cActFDCAct/SignificantAmendmentsto- theFDCAct/FoodandDrugAdministrationAmendment- sActof2007/FullTextofFDAAA Law/default.htm [24] Hirsch, L. (2008) Trial registration and results disclosure: Impact of US legislation on sponsors, investigators, and medical journal editors. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 24, 1683-1689. doi:10.1185/03007990802114849 [25] Mayor, S. (2005) Drug companies agree to make clinical trial results public. BMJ, 330, 109. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7483.109 [26] PhRMA (2009) Revised clinical trial principles reinforce PhRMA’s commitment to transparency and strengthen authorship standards (press release), Washington DC. http://www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/800/042009_clin ical_trial_principles_final.pdf [27] Taylor, P. (2009) Emerging clinical trial locations— China. Market dynamics and regulatory environment. Business Insights Ltd, London. [28] Abdullahi vs. Pfizer Inc., 562 F.3d 163, 169 (2nd Cir. 2009). [29] European Commission (2005) Notice to Applicants. Questions & answers: Clinical trial documents, F2/BL D 2005, Brussels. http://www.ct-toolkit.ac.uk/_db/_documents/ClinicalTrial Q&A_24-01-05.pdf [30] Department of Health, UK. (2004) EU Clinical Trials Directive: Sponsorship responsibilities in publicly funded trials. Medicines for human use (Clinical Trials) regula- tions 2004. http://www.ct-toolkit.ac.uk/_db/_documents/sponsorship. pdf [31] Gainotti, S. and Petrini, C. (2010). Insurance policies for clinical trials in the United States and in some European countries. Journal of Clinical Research & Bioethics, 1, 1-8. doi:10.4172/2155-9627.1000001 [32] Robinson, K. and Andrews, P.J. (2010) More trials and tribulations: The effect of the EU directive on clinical tri- als in intensive care and emergency medicine, five years after its implementation. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36, 322-325. doi:10.1136/jme.2009.035261 [33] Meunier, F. and Lacombe, D. (2003) European Organisa- tion for Research and Treatment of Cancer’s point of view. Lancet, 23, 663. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14163-3 [34] Ono, S. and Kodama, Y. (2000) Clinical trials and the new good clinical practice guideline in Japan. An eco- nomic perspective. Pharmacoeconomics, 18, 125-141. doi:10.2165/00019053-200018020-00003 [35] ICREL (2011) Report of project “Impact on Clinical Research of European Legislation”. http://www.efgcp.be/icrel [36] Therasse, P., Eisenhauer, E.A., Buyse, M. (2006) Update in methodology and conduct of cancer clinical trials. European Journal of Cancer, 42, 1322-1330. doi:10.1016/J.ejca.2006.02.006  R. R. Ciuman / Health 3 (2011) 772-781 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 781781 [37] Hemminki, A. and Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P.L. (2006) Harmful impact of EU clinical trials directive. BMJ, 332, 501-502. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7540.501 [38] Morice, A.H. (2003) The death of academic clinical trials. Lancet, 361, 1568. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13211-4 [39] Berendt, L., Hakansson, C., Bach, K.F., Dalhoff, K., Andreasen, P.B., Petersen, L.G,. Andersen, E. and Poulsen, H.E. (2008) Effect of European clinical trials directive on academic drug trials in Denmark: Retrospective study of applications to the Danish Medicines Agency, 1993-2006. BMJ, 336, 33-35. doi:10.1136/bmj.39401.470648.BE [40] Singer, E. (2007) Future of investigator initiated trials in EU academia. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxi- cology, 101, 11. [41] Gulland, A. (2009) Number of global clinical trials done in UK fell by two thirds after EU directive. BMJ, 338, 1052. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1052 [42] The Commission of the European Communities (2005) Commission Directive 2005/28/EC of 8 April 2005. OJL, 91, 13-19. [43] European Forum for Good Clinical Practice (EFGCP) (2010) A road map initiative for clinical research in Europe. http://www.efgcp.be [44] Federation of the European Academics of Medicine (FEAM) (2011) Opportunities and challenges for reforming the EU clinical trials directive: An academic perspective: State- ment. http://www.leopoldina.org/fileadmin/user-upload/politik/ Empfehlugen/FEAM/FEAM_Statement_EU-clinical-trial s-directive_2010.pdf [45] European Forum for Good Clinical Practice (EFGCP) (2011) Conference report: Examining the value and the impact of the EU clinical trials directive-one year into the new European GCP reality. http://www.efgcp.be/Downloads/EFGCP%20News%20 Winter%202005.pdf [46] Demotes-Mainard, J. and Ohmann, C. (2005) European clinical research infrastructures network: Promoting harmo- nization and quality in European clinical research. Lancet, 365, 107-108. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17720-4 [47] Demotes-Mainard, J., Chene, G., Libersa, C. and Pignon, J.P. (2005) Clinical research infrastructures and networks in France: Report on the French ECRIN workshop. Therapie, 60, 183-199. doi:10.2515/therapie:2005023 [48] Bergmann, L., Berns, B., Dalgleish, A.G., von Euler, M. and Hecht, T.T. (2010) Investigator-initiated trials of tar- geted oncology agents: Why independent research is at risk? Annals of Oncology, 21, 1573-1578. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq018 [49] Clumeck, N. and Katlama, C. (2004) Call for network of centers of excellence in clinical research in Europe. Lan- cet, 363, 901-902. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15757-7 [50] European Commission (2006) Guidance document on specific modalities for non-commercial clinical trials re- ferred to in commission directive 2005/28/EC laying down the principles and detailed guidelines for good clinical practice. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/pharmacos/docs/doc2006/ 07_2006/guide_noncommercial_2006_07_27_en.pdf [51] Moniteur Belge, Belgium. Loi relative aux Experimenta- tions sur la Personne Humaine; 7 May 2004. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?lan guage=fr&la=F&cn=2004050732&table_name=loi [52] Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) (2010) Research and development working group. Feasibility and challenges of independent research on drugs: The Italian medicines agency experience. European Journal of Clinical Inves- tigation, 40, 69-86. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02226.x

|