Journal of Service Science and Management, 2011, 4, 499-506 doi:10.4236/jssm.2011.44057 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies Andrew Sulle Mzumbe University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. E-mail: sullea@yahoo.co.uk Received June 7th, 2011; revised August 3rd, 2011; accepted September 2nd, 2011. ABSTRACT One element of the NPM-inspired reforms is the adoption of result-based management in the Tanzanian public sector. This paper examines the implementation of this type of reform by focusing on executive agencies. Executive agencies were especially created to be result-oriented public organizations. Our empirical question is whether or not and to what extent the management of executive agencies has shifted to result-based approach as promised by NPM-reform doctrine. Our findings indicate that result-based approach has only been partially implemented in the Tanzanian public sector. There is less emphasis on managing fo r results and management processes have continued to be predominantly based on inputs and processes. Keywords: Public Administration, Result-Based Management, NPM, Executive Agencies an d Reform in Tan zania 1. Introduction One of the central features of the current public sector reforms is the emphasis on performance results. Manag- ing for results requires the government to focus on the performance outputs/outcomes of its organizations in- stead of their administrative processes. This new approa- ch has been enthusiastically embraced by many countries [1] following the rise of New Public Management (NPM) doctrine. The NPM doctrines suggest that improving the performance of public services demands a focus on re- sults while providing public managers greater authority over their fiscal and human resources management. In addition, this reform requires political leaders to set out performance objectives and results, determine the level of resources to be used and devolve implementation tasks to low level administrative managers [2,3]. Result-based management approach is clearly related to the NPM reform movement that began initially in the West, notably in Australia, the UK, the US and New Zealand [1]. However, in recent years a number of de- veloping countries have also adopted this approach as a “management tool” to restructure and improve the per- formance of their public sector organizations [3,4]. In Tanzania, the recent public sector reforms also embraced this management approach. For many developing coun- tries such as Tanzania, th e adoption of this reform strate- gy has been partly based on their inspiration for such reforms in the West. The role of international donors such as the World Bank and IMF in encouraging develo- ping countries to adopt result-based management app- roach has also been recognized in the literature [4,5]. What is, however, not very clear up until now is whether and to what extent the result-based management approa- ch has been implemented in the Tanzanian public sector. It is now more than ten years since this reform was in- troduced in Tanzan ia, and yet little has been documented regarding its success or drawbacks. In the West, Moyni- han [1] reports that although there is a widespread adop- tion of the result-based management reform, definitive empirical evidence on whether these reforms have had desired outcomes were not forthcoming. For Tanzania, our knowledge is even limited as to whether this reform has moved further from the point of adoption1. This arti- cle examines the introduction and the practice of result- 1In our study we distinguish between a reform adoption and its imple- mentation. Adoption in our case refers to a situation where reform olicy is officially enacted (declared) whereas policy implementation means that reform is actually put to practice. In reality, policy statement (adoption) may never be fully or only partially implemented. Therefore in this sense, a policy adoption can be distinguished from the policy implementation process.  Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies 500 based management in the Tanzanian public sector, using executive agencies as its focal point. Executive agencies operate at arm’s length from their parent ministries and by their design, they are task-specific and result-focused public organizations. They are thus ideal organizations for our study. The main aim of the paper is to contribute to our understanding of how result-based management works in practice in Tanzania by addressing the follow- ing questions: To what extent is the resu lt-based manage- ment practice used in managing agencies? How has it worked in practice? The paper will proceed as follows. Following the in- troduction above, the next section provides an overview of the ‘managing for results approach’. Its central argu- ments will be discussed in connection to the cu rrent pub- lic sector reforms. The subsequent sections provide ba- ckground to the public sector reforms in Tanzania; data analysis on the implementation of th e result-based reform; a discussion and conclusions. 2. Managing for Results: An Overview Since the 1990s, the public sector has globally experien- ced a tidal wave of reforms that, among other things, fo- cused on performance management. The main focus of this reform brand was managing for results. Moyn ihan [6 ] describes management by results as a combination of strategic planning (systems that set organizational goals), performance measurement (systems that track and pro- vide information on cost and accomplishments of gove- rnment tasks), and some form of strategic/performance management (systems that shape working relationships and structure discretion in a way consistent with organi- zational goals). The appeal of this approach lies in its promise to enhance the performance of public sector or- ganizations. According to th e NPM, the traditional pub lic administration model performs poorly because it lacked explicit standards of performance and that there was no a strong result-based accountabilit y. Propon ents of NPM a- rgue that efficiency and effectiveness of public services can be achieved if governments adopt a focus on results while increasingly allowing managerial flexibility for policy implementation [1]. The result-based reform thus seeks to transform public sector into a flexible, dynamic, efficient and mission-driven institution. Managing for results requires governments to move away from an administrative culture of compliance, error avoidance, rigid rules and procedures, and presumed in- efficiency to a more efficient and effective public service management systems. It demands multiple changes to the existing public administrative systems that, for years, were based on the Weberian model [7]. First, the reform seeks to introduce a new role for parent ministries that of being strategic leaders while the task of implementing policies is delegated to professional bureaucrats, a proce- ss that can be described as the agencification of public service management [8]. This distribution of work bet- ween central ministries and their executive agencies en- tails decentralization. Following this distribution of roles and responsibilities, a further important element in the implementation of the result-based management is the identification and definition of objectives and indicators of expected performance results [9]. The political leader- ship (the parent ministry) must formulate clear perfor- mance goals and targets to be achieved, and give subor- dinate bodies a leeway and discretion in achieving these goals. Goals are to be defined in measurable terms that would allow a comparison of ex post performance with exante targets [10]. In addition, the government is ob- liged to provide enough resources for agencies to accom- plish their responsibilities [8]. Result-based management approach can be regarded as a management process that consist of interrelated su- bsystem [11]: a planning system (setting goals for agen- cies), a monitoring system (measuring agency perfor- mance results) and lastly an evaluation and feedback sys- tem (where sanctions and rewards are applied). As Lae- greid et al. [10], suggest the emphasis should be given to planning and the measurement of performance results. In addition, parent ministries must use information on re- ported results to reward good performance and punish bad. Moreover, central to the NPM reform prescription is the promise of greater efficiency in the public organiza- tions as a result of prov iding managers with greater free- dom to allocate resources, while holding them accounta- ble for results [7]. As a management tool, result-based approach is therefore a double-edged sword. It advocates both centralization and decentralization of public sector management [2]. The argument is that public managers would need some freedom to allocate resources in pursuit of their organizational goals. Line-item budgets should be discarded in favour of global budgets2 and that com- petencies for resources management should be devolved to the agencies [6,9]. In the context of the public sector this means that the agency is exempted from centrally determined rules and regulations regarding inputs man- agement [11]. Theoretically, agencies are thus free to make their own decisions on human resources and f inan- cial management issues such as recruitment, salary grad- ing, dismissal, promotions, evaluation of performance, and on financial management aspects such as setting tari- ffs, generating revenues and shifting budgets between 2In this arrangement, the resources (inputs) for policy delivery are as- signed for group of products as lump sum while specification for re- sources along categories of costs as in detailed resources plan is omit- ted. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies 501 different financial years, and in taking loans for further investment. These elements are traditionally the preroga- tive of central ministries such as the Civil Service De- partment and the Ministry of Finance. In the literature [11] the scope of managerial autonomy can further be sub-divided into strategic and operational managerial au- tonomy. Strategic autonomy is about the agen cy’s power to determine rules that governs human resources while operational autonomy is simply the ability of the agency to confer secondary benefits to its employees [11]. Owing to the intensification of pubic sector reforms in the past years, there is a need for detailed empirical scru- tiny of how such reforms have been implemented and to what extent the government of Tanzania has actually shifted the management of its organizations from the Weberian-based model to the result-based approach as advocated by NPM doctrines. As Christensen and Lae- greid [2] have argued, while certain reform effects are often promised and expected, they are seldom reliably documented. This study seeks to contribute to the grow- ing body of reform literature by studying the intro duction of result-based management in the public sector in Tan- zania. This article is of considerable interest to reformers and practitioners. For ex ample, by highlighting the ex tent to which result-based reforms were implemented or not, political actors may start to take stock of what has not worked and why. 3. Public Sector Reforms in Tanzania: Towards Result-Based Management System The background to the public sector reform in Tanzania is not very much different from that in other countries in Africa. The economic crisis in the 1980s and poor per- formance of public sector ignited far reaching public sector reforms. The reforms aimed at halting the expan- sion of the public sector size and to enhance its opera- tional efficiency. For example, since independence up until the 1990s, there has been a steady rise in the num- ber of people recruited in the public sector in Tanzania. As McCourt and Solla [12] noted, the policy of africani- zation3 between 1961 and 1970s saw an increase in a number of civil servants in many professional areas. The situation was further exacerbated by the politicization of civil service especially when Tanzania adopted the so- cialist policy in 1967. Under socialism, employment in the public sector was rather driven by the socialist ideo- logy and political patronage rather than clear manage- ment rationality. This not only compromised the produc- tivity of public secto r but it also expand ed the size of pu- blic service. Thus by 1984, more than 72% of formal sector emplo- yment was in public sector, and in 1989 a Report by the World Bank found that between 1970 and 1984, public service employment had expanded at roughly twice the rate of government revenues [12]. In addition, civil ser- vice was poorly performing, riddled with corruption, de- motivated and lacked the capacity to manage market-led economic policies which the government had embraced in the 1980s [13]. The government of Tanzania officially launched the Civil Service Reform Programme (CSRP) in 1993 with the objective of creating a ‘smaller, affordable, well-co- mpensated, efficient and effectively performing civil se- rvice’ [13]. The reform focused not only on institutional restructuring of the civil service but also in introducing new ideas and techniques in the management of public services. As result of the reform efforts, the government instituted a number of r eform measures inclu ding the crea- tion of executive agencies that are placed at arm’s length from their parent ministries [14]. Executive agencies are an important element of the result-based management system. Agencies can best be described as a tool for “unbundling the traditional bu- reaucracy” in order to create more flexible, and per- formance-oriented public organizations [15]. As Caul- field [2] noted, their appeal follows a widespread shift to business-like forms of managing public sector in pursuit of improving efficiency and effectiveness of public ser- vice delivery. The creation of agencies with clearly specified, single-purpose tasks will, it is assumed, in- crease transparency of government operations [2]. In an ideal-agency model, agencification allows for managerial autonomy by decentralizing decision-making competence in all areas of their management (including financial and human resource management) to Chief Executive Offi- cers (CEOs). In turn, the CEO is made accountable for achieving specified results. In general, the relationship between the parent ministry and their agencies is to be regulated through performance contracts than through normal government—wide public sector regulations. The executive agency programme was officially adop- ted in Tanzania in 1997. The policy expectation is that agencies will conform to the modern management prac- tices by developing strategic and business plans. Follow- ing years of poor performance of the public sector, the agency model was seen as an organizational solution, which would keep public services within the government, while promising efficiency and effectiveness of public service delivery [2]. Since the 1990s executive agencies have been created in various ministries. As of August, 2007 there were 24 executive agencies scattered in dif- ferent ministries. They perform various public tasks and are formally managed at arm’s length by their parent mi- 3This was about replacing departing colonial bureaucracy with indige- nous Tanzanians. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies 502 nistries. The agency is headed by a CEO, who is recrui- ted through an op en competition for a renewable contract of 5 years. According to the agencification policy, parent ministries would set out performance goals, targets and monitor their agencies on the bases of performance re- sults. This reform policy demands ministers and parent ministries in general to refrain from interfering in the day-to-day management of the agencies (The Executive Agenc y Act no .3 0.1 997 ). It has b een in s ist ed tha t th e ro le of parent ministries should be limited to that of setting strategic direction for agencies and to ensure that agen- cies are held accountable for achieving performance re- sults. Since executive agencies are, by their design, result- focused organizations, we expect result-based manage- ment practice to be more robust. As elaborated earlier, the working relationship between agencies and their par- ent ministries is expected to be based on performance contracts in which agencies are given more managerial autonomy in return fo r performance-based accountability. This article seeks to explore to what extent this policy rhetoric has been put to practice in Tanzania. 4. Data Base This study is empirically based on the public sector in Tanzania. Following a review of the current literature on public sector reforms in Tanzania, we draw on a survey questionnaire addressed to the CEO of all 24 executive agencies in Tanzania. This survey was conducted at the beginning of 2008. CEOs were asked to fill in a survey questionnaire covering all aspects related to autonomy, control and the agencies’ performance. The response rate was 78%, thus making us conclude that the respondents are quite representative of the population of agencies in Tanzania. In Tanzania all executive agencies are estab- lished under a single legislation, the Executive Agency Act, No.30, 1997, and it is thus easy to delineate agen- cies from other public organizations. 5. Empirical Findings Results-Based Management in Tanzania As elaborated earlier, there are two aspects of the result- based management approach in general. The first aspect is that of parent ministries setting performance goals for agencies, then monitoring, evaluating and applying sanc- tions and rewards according to the agencies’ performance level. This can be summarised as “making managers ma- nage”. The seco nd asp ect is that of “letting manag ers ma- nage”. This entails giving agencies more managerial au- tonomy. In this analysis, we first examine the managerial autonomy of agencies in Tanzania before we present the data on the extent to which agencies are subjected to a result-based control. 6. Agencies’ Managerial Autonomy Empirical findings for the level of agencies’ managerial autonomy are provided in Table 1. The table shows both the level of strategic and operational managerial auton- omy for agencies. As indicated, executive agencies in Tanzania have less strategic managerial autonomy in hu- man resources and in some aspects of financial manage- ment. These data indicate that most agencies, if not all, are not allowed to have their own human resources pol- icy or strategic decisions on vital areas such as employ- ment and salary levels for their employees. The extent of agencies’ autonomy is lowest on decisions about salary setting (5.6%), setting condition for employing new staff (22%), and in determining the work force size (33.3%). These strategic managerial elements are still predomi- nantly centrally controlled (Public Service Management and Employment Act, 1999). More specifically, employ- ment needs in the agencies must be approved centrally by the Civil Service Department and the Treasury [16]. This is contrary to the NPM doctrine which requires the eli- mination of centralized human resources rules and regu- lations. The aim of the NPM administrative reform was to remove the centralized Weberian rules, which make it hard for public managers to hire, fire, redeploy and set their salary policies according to their circumstances. After a decade of the agencification reforms, the Tanza- nian government seems to be reluctant to provide agen- cies with these key elements of managerial autonomy. Further more, whereas 77.8% of agencies responded that they can effect promotion, 88.9% agree that they can as well evaluate the performance of individual staff. In addition, most agencies (83%) have gained the freedom to set themselves the level of fees they can charge their customers for the goods and services they produce. There are however, some sensitive public services that the go- vernment can not let the agencies to set charges freely, even at the prevailing market price. For instance, one agency, (TEMESA) runs several fer- ries in some major rivers, lakes and along the Indian O- cean coast, mainly for the purpose of providing public transport. Despite huge running costs, these ferries still charge the lowest possible fare (eg. US$ 0.13 per adult for a Dar es Salaam-Kigamboni trip, a distance of about 0.5 km) and although the agency may wish to increase that fare, the final decision was still in the hand of the parent ministry. Tanzania Building Agency (TBA) also faces a similar fate. The agency’s core task is to build houses, first for public servants and individuals, but it can also sell or let to private firms or individuals. Whereas for private firms and private individuals, the agency has the liberty to set charges according to the prevailing market rates, but with respect to houses for public servants the rate is normally determined by the government. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 503 . Table 1. The level of agencies’ autonomy along various managerial dimensions. Response from agencies in categories Variable: Autonomy in Measurement: Whether the agency is allowed do the followin g Yes % No % Total N- 1. Setting salary level 1 5.6 17 94.4 18 2. Setting general conditions for promotion 8 44.4 10 55.6 18 3. Determining the size of agency (number of staff) 6 33.3 12 66.7 18 Strategic Human Re- sources Management 4. Setting conditions for Employment 4 22 14 77.8 18 1. Rewarding well performing staff 15 83.3 3 16.7 18 2. Promoting individual staff 14 77.8 4 22.2 18 3. Wage increase for individual staff 2 11.1 16 88.9 18 4. Evaluating individual staff 16 88.9 2 11. 1 18 Operational Human Resources Management 5. Transferring staff between uni ts within t he agency 17 94.4 1 5.6 18 1. Taking loans. 3 16.7 15 83.3 18 2. Setting tariffs/prices for their goods and services 15 83.3 3 16.7 18 3. Participating in private law 1 5.6 17 94.4 18 4. Shifting budget between Personnel & other costs 2 11.1 1 6 88.9 18 Financial Managerial Autonomy 5. Shifting funding/budget between different years 14 77.8 4 22.2 18 Source: Survey, 2007. Following these two examples, it seems that to some extent, in politically sensitive public services, the gov- ernment may intervene in setting charging rates for a- gencies’ services. It is also worth noting that there is of- ten a general resistance within the government to let a- gencies charge for services that are “consumed” by gov- ernment departments. At the launch of the agency pro- gramme, the government had anticipated internal markets for agencies’ services when it said “agencies will receive income from trading with government departments and other customers”. This has turn out to be problematic for agencies, particularly those whose major customers are government ministries and departments. For example, Public Service Report Programme (PSRP 2006) observ ed that although many agencies would want to charge mar- ket-level fees for their products so as to generate reve- nues, government departments and ministries took a tra- ditional view and resent to pay for services they received from the agencies. Similarly, Caulfield [2] argues that mi- nistries have failed to see why they should pay for the services provided by their units. She also notes that the general public in Tanzania had a trouble of coming to terms with new “user fees” environment. One reason for this could be the legacy of Ujamaa4 policy, in which pu- blic services were heavily subsided or were provided freely by the government. Agencies seem to have gained considerable discretion over how they can manage their global budgets. As noted in the Table 1, agencies can retain unspent monies and transfer the same budget between different financial years (77%). They cannot, however, shift budget between per- sonnel and other costs for obvious reasons. In almost all agencies, personnel salary is still paid by the treasury and therefore agencies do not have any discretion over it. 7. Managing Results for Executive Agencies The creation of agencies was expected (theoretically) to result in agencies being controlled by performance re- sults. In principle, control on inputs was supposed to be replaced by a result-based control. Key elements of the result-based control have been identified as goal/object- tive setting together with their quantifiable performance indicators against which the results are measured; the process of performance monitoring and evaluations fol- lowed by rewards and sanctions according to the level of performance achieved. In what follows these manage- ment aspects are empirically examined. Our empirical data indicate that parent ministries are not largely involved in setting performance goals and in- dicators for their agencies. In most cases, executive agen- cies have been left to develop their own performance objectives. For example, most agencies (83%) indicated that they set their own performance goals as well as per- formance targets. Similar observations can also be drawn 4This is the Tanzanian version of Socialism.  Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies 504 from some previous research. According to Ronsholt and Andrew [17] agencies have been left to develop their own performance target without necessarily getting ap- proval from their parent ministries. In our research we observed that it was only the Tanzania National Roads Agency (TANROADS) whose performance objectives are set by the government through the Ministry of Infra- structure Development and the Road Funds Board5. In addition, TANROADS is the only agency that signs an- nual performance contracts with these two oversight au- thorities that are jointly responsible for its performance. For example, while all road maintenance works are funded by the Road Funds Board (RFB) the development of new road projects is generally funded by the parent ministry, mainly through donor funds. In this scenario, TANROADS signs two performance contracts annually: one with the parent ministry and other with the Road Funds Board. Each oversight authority develops its own performance goals for TANROADS and then monitors the implementation. The reason why the government was interested in the performance of this agency is beyond the scope of this work. Another aspect of result-based management approach is the presence of performance indicators that would help political leadership to evaluate how agencies have achie- ved their performance objectives. In the UK, these are called the minister’s performance indicators and they are developed by the parent ministry [2]. In Tanzania, parent ministries are not generally involved in developing per- formance indicators for their agencies. As part of their annual business plans, agencies develop their own per- formance indicators and these business plans are dis- cussed during the annual meetings of the Ministerial Ad- visor y Board s (MA B). In ad dition , ag enc ies also eva lua te their own performance (50%) and only a few (38%) said that their respective parent ministries do evaluate their performance. In Tanzania, the notion of monitoring the perfor man c e of ex e cutive agen c ie s th rou gh th e pr o c es s of measuring and evaluating results is poorly developed. Ronsholt and Andrew [17] also noted a real lack of par- ent ministries in developing indicators and in monitoring the performance of agencies. According to them the real interest of parent ministries is to extract financial surplus from their agencies than to see how agencies performing their tasks. Earlier Caulfield [2] also noted a seriou s lack of performance monitoring for agencies in Tanzania: no parent ministry we visited has a performance monitoring regime in place…there have been no pressure on the agencies to produce an annual reports. Indeed, result-b ased accountab ility was supposed to be linked to clear incentives for results and possibly sanc- tions for bad performance [6]. Yet, our empirical data indicate that Tanzan ia is lagging behind in implementing this reform aspect. The overall picture from our analysis is that sanctions and rewards are not strongly emphasized in the management of agencies. First, if parent ministries are, as we have already seen, less interested in setting performance objectives for agencies and are not doing actual evaluation of their agencies’ performance, there is no strong way the government can reward good per- formance and punish the bad ones. Improved information about the performance of agencies could have been used to allocate praise or blame, and indeed the same can be used to inform decisions about resources allocation to agencies including their staffing levels. In Tanzania these monitoring elements are not emphasized in managing the agencies. 8. Concluding Discussion The main focus of this article was on the imp lementation of the result-based management in Tanzania by focusing on the executive agencies. Informed by NPM ideas the initial assumption was that agencies would be managed on the basis of results and that their managerial auton- omy will be enhanced. When the agencification pro- gramme was introduced in Tanzania in the 1990s the official rhetoric was to move away from inputs and pro- cess focused-management approach to outputs-based management approach [14]. The policy intention of the agencification reform was to dis-bundle monolithic tradi- tional bureaucracies into tasks specific and results-focu- sed agencies that are to be given more managerial auto- nomy in delivering public services within a prescribed resources and performance accountability. It was insisted that parent ministries would set strategic direction and performance objectives for their agencies while monitor- ing them on the basis of performance outputs (Executive Agency Act, No.30, 1997). Instead of hierarchical con- trol, the agency model was formed on the precepts of principal-agent model where the relationship between agencies and their parent ministries was to be moderated through performance contracts. As demonstrated, our main finding in this research is that the government of Tanzania has continued to man- age executive agencies mainly on the basis of the Webe- rian model (inputs and processes), than the expected re- sult-based control. Although the NPM doctrine calls for the creation of performance-based accountability while dismantling traditional financial and personnel control systems, this has not been fully embraced in Tanzania. The traditional civil services systems have remain largely in place in managing agencies, and the government has 5This is a special and dedicated Fund established by the Act of Parlia- ment to ensure that Roads works have a stable and identifiable source o funding. The Fund mainly receives its revenue from fuel levy taxed fo every litre of petrol sold at a pump in the countr y. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies 505 even continued to enforce this approach, sometimes th- rough legislation (Public Service Management and Em- ployment Policy, 1999). Th is Policy, although developed at a time when policy makers in Tanzania were already aware of the basics of the NPM doctrine, has further cen- tralized and placed the management of Civil Service in the hands of PO-PSM. The PO-PSM (the Civil Service Department) has retained its traditional power to formu- late, review and evaluate human resources policies in the entire public service, leaving line ministries and agencies with very little freedom [16].This contrasts the NPM’s philosophy of giv ing agen cies more autonomy to manage their staff in a businesslike way. While NPM ideas seem to have been ab le to partially influ ence structural reforms (we mean the process of putting agencies at arm’s length from their parent ministries), this reform process was not able to break the institutional th inking and thus the pro c- ess of controlling agencies. The preference for h ierarchi- cal control, which is embedded in the management of pu- blic sector in Tanzania, is most visible when we look at the agencies’ managerial autonomy. Most agencies dis- play low strategic managerial autonomy. Agencies still need prior approval from their parent ministries and in- deed from central ministries such as the PO-PSM and the Treasury for most of the HRM and financial management. Within the agencies, the tradition of financial audit also seems to be more dominant than the result-based audit, which is encouraged by the NPM doctrines so as to a- chieve the so called ‘value for money’ [18]. It was also striking to note a general absence of the strategic steering by ministries as envisaged by NPM doctrines. According to NPM reform doctrine elected o- fficials or parent ministries would set the goals and hold bureaucrats accountable for achieving those goals [6]. This promise, has however, not been fulfilled in Tanza- nia. As noted earlier, the task of developing performance goals was mainly left to agencies themselves and in ma- ny instances agencies have taken themselves a lead in e- valuating their own performance. In her research in 2002, Janice Caulfield also reported the same observations. She noted that… most agencies have been left to develop their own operational targets without necessarily even getting formal approval from their parent ministries about what they should be. Moreover, Permanent Secre- taries appear to be unsure about their role as strategic managers and that parent ministries were disinterred in monitoring and evaluating agencies performance. This paper’s observation is not dissimilar. Agencies face a weak result-based control. Performance monitoring and evaluation are weak and performance results plans are poorly developed. To some extent, parent ministry’s in- terest was in the financial performance. In this regard, one senior manager has this to say ‘since Permanent Se- cretary is the accounting officer in the ministry, financial management in the agencies is of great interest to him to avoid public or Parliamentaty Committee queries for any misuse of funds in the agencies’ [18]. Furthermore, in the ideal-NPM agency model, it is the contractual relationship which provides the link between agencies and their parent ministries. In Tanzania the pat- tern of control is rather complex and the tools of govern- ing agencies are somehow ambiguous. There is much use of traditional bureaucratic mechanisms in controlling a- gencies, but these are also not used in any systematic and sophisticated way. Our general conclusion is that the age- ncification reform in Tanzania has not resulted in a shift from the traditional (Weberian) approach to the result- based approach as envisioned in the NPM doctrines. Bo- th agencies’ autonomy and result-control are weak when examined from the NPM perspectives. Management of public human resources in Tanzania is politically salient and may not be easily delegated to the agencies. It in- volves both resources and patronage distribution in the public sector, things that are politically sen sitive. As a re- sult the finding in this paper suggests that the result- based control has only been partially introduced in Tan- zania. 9. Further Research This research paper is generally a descriptive analysis of the implementation of the result-based management re- form for the executive agencies in Tanzania. It highli- ghted the limited implementation of the reform without delving into the question of why reform has not been successfully implemented. Further research could addr- ess the question of why this reform has only been par- tially implemented in Tanzania. Such research could be done from many interesting theoretical perspectives. For example, one important argument in the literature is that most developing countries do no have the required ad- ministrative capacity to implement sophisticated admin- istrative reforms based on NPM ideas [19]. Likewise, others have suggested that most NPM ideas are somehow incompatible with administrative cultures of most devel- oping countries [20]. These factors may shed light into the question of why NPM reform elements such as the result-based management approach has failed to take root in the Tanzanian public sector. REFERENCES [1] D. D. Moynihan, “Managing for Results in State Gov- ernment: Evaluating a Decade of Reform,” Public Ad- ministration Review, 2006. [2] T. Christensen and P. Laegreid, “Regulatory Agencies- The Challenges of Balancing Agency Autonomy and Po- litical Control,” Governance, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2007, pp. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 506 499-520. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00368.x [3] J. Caulfield, “Executive Agencies in Tanzania: Liberali- zation and Third World Debit,” Public Administration and Development, Vol. 22, No. 200, pp. 2209-2220. [4] G. Larbi, “Performance Contracting in Practice; Experi- ence and Lessons from the Water sector in Ghana,” Pub- lic Management Review, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 305-324. doi:10.1080/14616670110044018 [5] C. Polidano, “Why Civil Service Reforms Fail; IDPM Public Policy and Management,” Working Paper no.16. 2001. [6] D. Moynihan, “Why and How Do State Governments Adopt and Implement Managing for Results Reforms? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Vol. l, No. 15, 2005, pp. 219-243. [7] R. Norman and R. Gregory, “Paradoxes and Pendulum Swings: Performance Management in New Zealand’s Public Sector,” Australian Journal of Public Administra- tion, Vol. 62, No. 4, 2003, pp. 35-49. doi:10.1111/j..2003.00347.x [8] M. Tiili, “Strategic Political Steering: Exploring the Qualitative Change in the Role of Ministers after NPM reforms,” International Review of Administrative Science, Vol. 73, No. 81, 2007, pp. 81-94. doi:10.1177/0020852307075691 [9] I. Proeller, “Outcome-Orientation in Performance Con- tracts: Empirical Evidence Rom Swiss Local Govern- ments,” International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 73, 2007, pp. 95-110. doi:10.1177/0020852307075692 [10] P. Lægreid, P. Roness and K. Rubecksen, “Performance Management In Practice: He Norwegian Way, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2006, pp. 251-270. doi:10.1111/j.0267-4424.2006.00402.x [11] K. Verhoest, B. Peters, G. Bouckaert and B. Verschuere, “The Study of Organizational Autonomy: A Conceptual Review,” Public Administration and Development, Vol. 24, 2004, pp. 101-118. doi:10.1002/pad.316 [12] W. McCourt and N. Solla, “Using Training to Promote Civil Service Reform: A Tanzanian Local Government Case Study,” Public Administration and Development, Vol. 19, 1999, pp. 21-32. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-162X(199902)19:1<63::AID-PA D55>3.3.CO;2-6 [13] D. Ntukumazina, “Civil Service Reform in Tanzania: A Strategic Approach,” In S. Rugumamu, Ed., Civil Service Reform In Tanzania: Proceedings of the National Sympo- sium, Dar es Salaam, 1998. [14] J. Rugumyamheto, “Innovative Approaches to Reforming Public Services in Tanzania,” Public Administration and Development, Vol. 24, 2004, pp. 437-446. doi:10.1002/pad.335 [15] C. Pollitt, C. Talbot, J. Caulfield and A. Smullen, “Agen- cies: How Governments do Things through Semi-Au- tonomous Organizations,” Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2004. [16] B. Bana and W. McCcourt, “Institutions and Governance: Public Staff Management in Tanzania,” Public admini- stration and development, Vol. 26, 2006, pp. 395-407. doi:10.1002/pad.423 [17] F. Ronsholt and M. Andrews, “Getting it Together or Not: An Analysisof the Early Period of Tanzania’s Move To- wards Adopting Performance Management Systems,” In- ternational Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 28, 2004, pp. 313-336. [18] A. Sulle, “The Application of New Public Management Doctrine in Developing World: An exploratory study of Autonomy and Control of Executive Agencies in Tanza- nia,” Public Administration and Development, Vol. 30, No. 5, 2010, pp. 345-354. doi:10.1002/pad.580 [19] A. Sarker, “New Public Management in Developing Countries: An Analysis of Success and Failure with Par- ticular Reference to Singapore and Bangladesh,” Interna- tional Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2006, pp. 180-203. doi:10.1108/09513550610650437 [20] A. Schick, “Why Most Developing Countries Should Not Try New Zealand’s Reforms,” The World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1998, pp. 123-131.

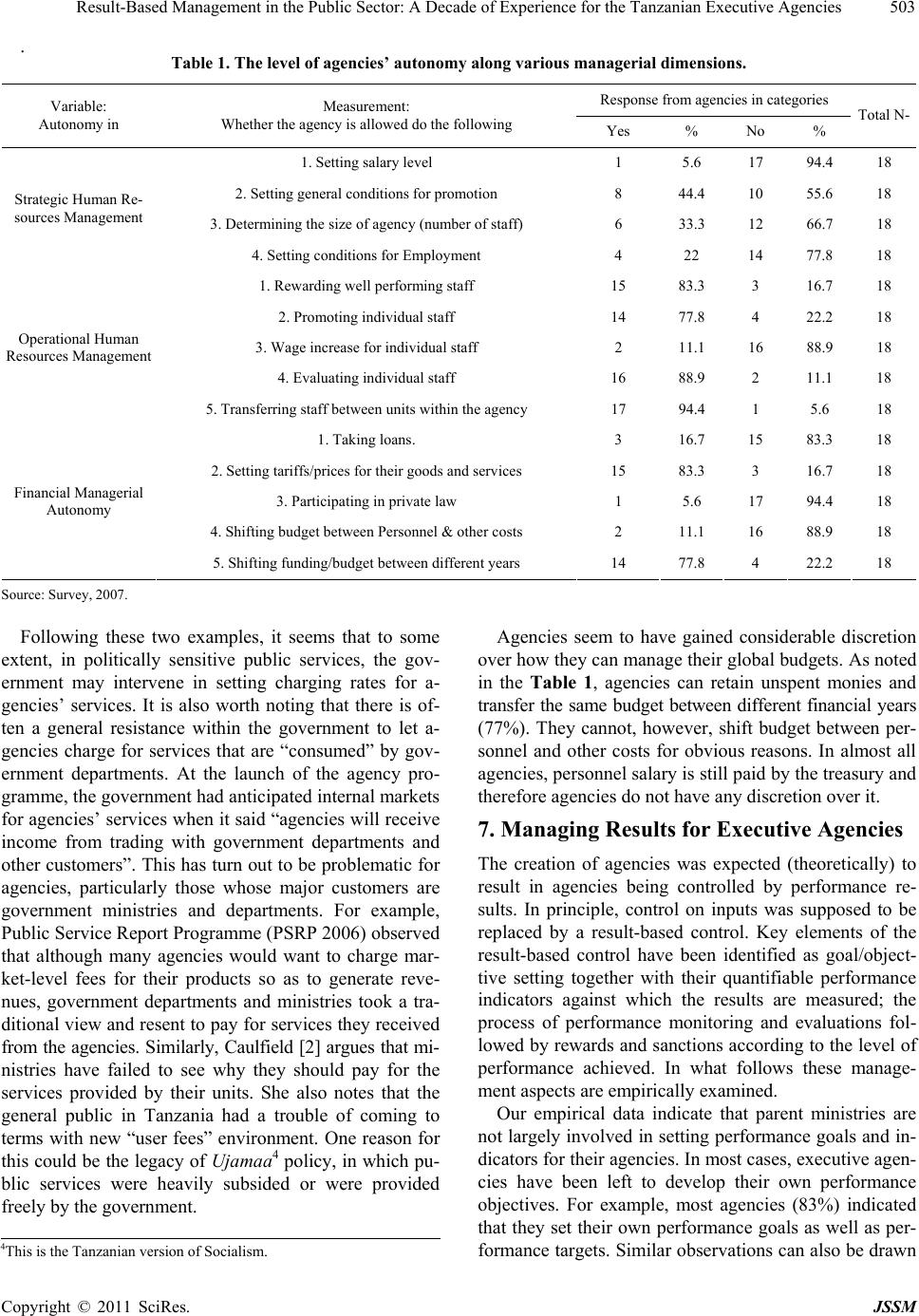

|