Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.08 No.03(2017), Article ID:74485,14 pages

10.4236/jmp.2017.83027

Planck’s h and Structural Constant s0

Milan Perkovac

University of Applied Sciences, Zagreb, Croatia

Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: January 20, 2017; Accepted: February 25, 2017; Published: February 28, 2017

ABSTRACT

Application of Maxwell’s equations and the theory of relativity on the processes in atoms with real oscillator leads to the structural constant of atoms s0 = 8.278692517. Measurements show that the ratio of energy of the photon and its frequency is not constant which means that Planck’s h is not constant. The theory which is consistent with these measurements, has been found. This theory covers processes in electron configuration and also at the core of atoms. Based on the structural constant s0 the maximum possible atomic number Z is determined. In order to encompass all atoms and all nuclides a new measurement unit has been proposed. That is the measurement unit for the order of substance. The introduction of structural constant s0 makes 11 fundamental constants redundant, including Planck’s h. The structural constant of atoms s0 stands up as the most stable constant in a very wide range of measurement, so it may replace variable Planck’s h well. Continuity of the bremsstrahlung is explained.

Keywords:

Boscovich, Bremsstrahlung, Hyperon, Neutron, Order of Substance, Planck, Redundant Constants, Soddy, Structural Constant

1. Introduction

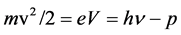

In addition to general interest reaching scientific truth, another motive for publishing this article is finding the answer to Millikan’s question about the linearity of frequency ν and voltage V in the famous Einstein’s formula of the photoelectric effect,  , in which

, in which  is the energy absorbed by the electron from the light wave, p is the work necessary to get the electron out of the metal,

is the energy absorbed by the electron from the light wave, p is the work necessary to get the electron out of the metal,  is the energy with which it leaves the surface, h is known quantity introduced by Planck in 1900 [1] . It is shown here that the answer to this question can only be made in a wide range of measurement, at voltages up to several tens kV, and that these ranges at that time (from just a few volts) were too small, as for other researchers (E. Ladenburg, Verh. d. D. Phys. Ges. 9, 504, 1907), thus also for Millikan’s experiments. Finally, this paper shows that there is no linearity between ν and V. In fact, it can be taken as this linearity exists at low energies (of several eV), and certainly not at high energies (of tens keV). This issue deals with, among others, also several contemporary researchers [2] - [9] .

is the energy with which it leaves the surface, h is known quantity introduced by Planck in 1900 [1] . It is shown here that the answer to this question can only be made in a wide range of measurement, at voltages up to several tens kV, and that these ranges at that time (from just a few volts) were too small, as for other researchers (E. Ladenburg, Verh. d. D. Phys. Ges. 9, 504, 1907), thus also for Millikan’s experiments. Finally, this paper shows that there is no linearity between ν and V. In fact, it can be taken as this linearity exists at low energies (of several eV), and certainly not at high energies (of tens keV). This issue deals with, among others, also several contemporary researchers [2] - [9] .

Planck’s h relates to the energy  of a photon to its frequency (ν) through the equation

of a photon to its frequency (ν) through the equation . This means that Planck’s h is defined as the ratio

. This means that Planck’s h is defined as the ratio

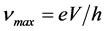

. The American physicists William Duane and Franklin L. Hunt (1915), in the article “On X-Ray Wave-Lengths”, Physical Review [10] , give the maximum frequency

. The American physicists William Duane and Franklin L. Hunt (1915), in the article “On X-Ray Wave-Lengths”, Physical Review [10] , give the maximum frequency  at the edge of the continuous spectrum of X-rays that can be emitted by bremsstrahlung in an X-ray tube by accelerating electrons through an excitation voltage V into a metal target. Afterwards the numerous experiments of other physicists [11] - [16] pointed to the conclusion that the ratios

at the edge of the continuous spectrum of X-rays that can be emitted by bremsstrahlung in an X-ray tube by accelerating electrons through an excitation voltage V into a metal target. Afterwards the numerous experiments of other physicists [11] - [16] pointed to the conclusion that the ratios  of energy and frequency of photon are constant. Thus was declared Duane-Hunt law,

of energy and frequency of photon are constant. Thus was declared Duane-Hunt law,  , where

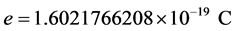

, where  is the elementary charge. This law is used to accurately determine Planck’s h. The three atomic constants, e, m and h are possible to measure with any real precision only in certain combinations, and the three simplest quantities that can thus be determined experimentally are e, e/m and h/e. R. T. Birge (1935) and J. W. M. DuMond (1939) have shown that there is an intolerable discrepancy of about

is the elementary charge. This law is used to accurately determine Planck’s h. The three atomic constants, e, m and h are possible to measure with any real precision only in certain combinations, and the three simplest quantities that can thus be determined experimentally are e, e/m and h/e. R. T. Birge (1935) and J. W. M. DuMond (1939) have shown that there is an intolerable discrepancy of about  to

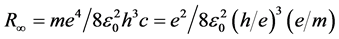

to  of a percent between measuring and calculating the Rydberg constant determined according to Bohr’s formula,

of a percent between measuring and calculating the Rydberg constant determined according to Bohr’s formula,

, where

, where  is electric constant. Because of that DuMond even concludes: “the possibility of revealing an important modification of theory in this way is also present” [17] . My statistical analysis of the results of said experiments has shown that the ratio

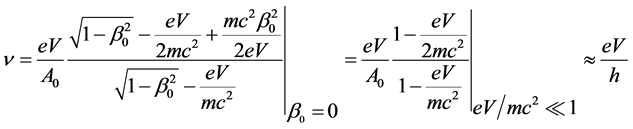

is electric constant. Because of that DuMond even concludes: “the possibility of revealing an important modification of theory in this way is also present” [17] . My statistical analysis of the results of said experiments has shown that the ratio  is not constant, i.e., Planck’s h is not constant [18] - [24] . Harmonious results between theory and measurements are obtained using relativity and one alternative law. The said law is found and used with the help of structural constant of atoms s0 = 8.278692517066260, [20] [24] . This law gives (let’s call it so) an extended Duane-Hunt’s law [24] , Equation (55):

is not constant, i.e., Planck’s h is not constant [18] - [24] . Harmonious results between theory and measurements are obtained using relativity and one alternative law. The said law is found and used with the help of structural constant of atoms s0 = 8.278692517066260, [20] [24] . This law gives (let’s call it so) an extended Duane-Hunt’s law [24] , Equation (55):

, (1)

, (1)

where  is the ratio of initial velocity

is the ratio of initial velocity  of the electron in the atom which is located in the target; the speed of light in vacuum is

of the electron in the atom which is located in the target; the speed of light in vacuum is

stand for the action constant [24] , Equation (48), where

The continuous spectrum of bremsstrahlung can be explained from Equation (1) as a result of the continuity of the initial velocity of the electron

2. Energy Relations in the Atoms

The total mechanical energy E of an electron in an atom is the sum of its kinetic energy K, and its potential energy U [26] [27] :

The kinetic energy of the electron, with mass m, moving at an arbitrary velocity

In [24] was found

where Z is atomic number;

where eV is electrical or (by an amount equal to it) electromagnetic energy Eem required for ionization of atom.

Using Equations (4) and (5) we record the kinetic energy:

We assume that the electron in an atom moves in a circular orbit. There is acceleration perpendicular to the direction of motion. With the Coulomb’s law applies [27] :

or

where r is the radius of curvature of the trajectory (in this particular case it is the radius of the circular orbit of the electron in atom), q = −e is electron charge, Q = Ze is the core charge,

Because of the law of conservation of energy, the part of it that is dissipated from the atom is electromagnetic energy Eem, which, on the other hand, is the amount equal to the total mechanical energy E of an electron, but with a negative sign [22] , which also represents the energy required for ionization of atoms eV:

With Equation (5), Equation (11) gives (see Figure 1):

3. Application of Structural Constant

Previous theoretical considerations and knowledge can be used for several different purposes. Here are three applications that are specifically enabled by the new findings, which enabled the discovery of structural constants of atoms

3.1. Connections of

Stable states and discretization appear in the atom as a result of the harmonization of two different periodical processes; electromagnetic oscillations and the circular motion of electrons [18] [19] and [24] . Equation (13) extended to other states of atoms (not just to the first state, i.e., not just

where

Figure 1. Structural constant of atoms s0 (green); Planck’s h (blue) as the ratio of energy Eem (gray) and frequency ν (golden) of a single photon; eV, the ionization energy of an atom derived theoretically (gray) and by the NIST data [25] (110 data, labeled ・), in a range from hydrogen (Z = 1, eV = 13.6 eV) to darmstadtium (Z = 110, eV = 204.4 keV). The theory is also consistent with other measurements, e.g., it is confirmed by Duane- Hunt and Kulenkampff measurement [20] (10 data, labeled ○). The difference between the measurements and the theory is <0.84%. This figure and calculations shows a theoretical matching with 120 experimental data ranging 1:15000, i.e., from 13.6 eV to 204.4 keV. The ratio Eem/ν in this area is clearly not constant. The only constant is s0. Other particles (for example, neutron and hyperons) subject to the same energy laws as well as a hydrogen atom inside energy states

speed of light,

On the smallest orbit (for

From Equations (13) and (14) results:

For example, by choosing discrete state

The mass M of hydrogen atom in the state of n = 1/126 is equal to the sum of the mass of the proton and the electron mass:

This mass correspond to the mass of neutron

where

stands as a mathematical abbreviation for the length L0 of the world of atoms. For

Now is from Equation (20) and with Z = 1:

According to the classical concept, Equation (23) is the orbital radius of the electron in the hydrogen, but this hydrogen due to the increased mass of the electron has a mass of neutron. As we see, in addition to well-known stable states

3.2. Order of Substance as the New Physical Quantity

There are currently 118 known elements with more than 3100 nuclides,

Table 1. A hydrogen atom in different states takes on the properties of the neutron, hyperon

a. The mass corresponds to the mass of hydrogen (mP + m = 938.272 + 0.511 = 938.783 MeV), 2014 CODATA, http://physics.nist.gov/constants. b. The mass corresponds to the mass of the neutron, 939.5654133 MeV, 2014 CODATA. http://physics.nist.gov/constants, [29] . c. The masses correspond to the masses of hyperon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Table_of_nuclides. A nuclide is an atomic species characterized by the specific constitution of its nucleus, i.e., by its number of proton Z, its number of neutrons N, and its nuclear energy state. The number of protons Z within the atom’s nucleus is called atomic number and is equal to the number of electrons in the neutral (non-ionized) atom. Each atomic number Z identifies a specific element, but not the isotope; an atom of a given element may have a wide range in its number N of neutrons. The number of nucleons (both protons Z and neutrons N) in the nucleus is the atom’s mass number A = Z + N, and each isotope of a given element has a different mass number.

With such a large number of nuclides or isotopes, there is a need for their sorting, classification and marking with the use of today’s knowledge. There are also disputes between nuclide concept and isotope concept. Nuclide refers to a nucleus rather than to an atom, because identical nuclei belong to one nuclide, for example each nucleus of the carbon-15 nuclide is composed of 6 protons and 9 neutrons. The nuclide concept (referring to individual nuclear species) emphasizes nuclear properties over chemical properties, whereas the isotope concept (grouping all atoms of each element) emphasizes chemical over nuclear.

No arbitration between the two concepts, it is best to make a clean substrate, with that later these concepts can any self-build further its goals. The existence of isotopes was first suggested in 1913 by the radiochemist Frederick Soddy, who explained, with Ernest Rutherford, that radioactivity is due to the transmutation of elements, now known to involve nuclear reactions.

Since Frederick Soddy deal and chemistry and a nucleus of atoms, just his name connects both of these areas, isotopes and nuclides. So my suggestion is to recognize and accept the existence of a new physical quantity, named the order of substance, that is signified with Soddy’s name, S, so-called Soddy’s number, covering the whole substances with properties of atoms and their nuclei. Any physical quantity has its own unit of measurement. Because this is not only about counting, but it is a combination of different properties of atoms, as new quality, this current quantitative measurement unit (mole) is not suitable for expression of Soddy’s number. Soddy’s number requires a new unit of measurement. The idea is that each nuclide gets its own unique and easily definable number.

In this sense, can be used the knowledge of the maximum possible number of different atoms,

where

this gives:

It is estimated that number of neutrons in a nucleus certainly not exceeds one thousandth (and therefore we put

The Soddy’s number for the carbon, with Z = 6 and N = 7, for example, is:

The Soddy’s number for vacuum (Z = 0, N = 0) is S(0,0) = 0.000 B, for neutron

3.3. The Redundant Constants

After the discovery of structural constant of atoms

Table 2. The proposal of SI base units with addition of a new physical quantity called the order of substance with a sign of that quantity S, in honor to radiochemists Frederik Soddy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Soddy, and with unit name “boscovich”a, unit symbol B, in honor to Roger Joseph Boscovich (Croatian: Ruđer Josip Bošković), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Joseph_Boscovich, who is the precursor of atomistic.

a. “boscovich” is a unit of order of substance amount B = 1/(2s02 + 1) = 1/138.073499584258 = 0.0072425194046.

is associated with the fine-structure constant

If we share the action constant

Action constant

A point charge Q created at a distance r from the charge (relative to the potential at infinity, where this potential is calculated as a Zero) the electric potential difference

so that the potential energy U of the charge q, according to Equation (10), is

When moving charge q (masses m) is on the potential

whereas according to Equations (11) and (13) applies:

From Equations (1), (5), (11) and (33) results [24] :

If we divide Equation (35) with potential

The Equation (35) we can now write with the help of Equation (36):

The Equation (37) has the same shape as the equation of the frequencies in the alternating-current Josephson effect, (

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josephson_effect, where

From [18] , Equation (70), comes

where

Using Equations (13) and (20) the magnetic dipole moment [26] associated with an electron orbit is given by

where I is the electric current and A is the area of the loop, and T is the time required for one orbit (see Table 3).

Table 3. Initial and derived (redundant) fundamental constants.

a. Difference value in relation to the Committee on Data for Science and Technology, 2014 CODATA. b. Here σ is the structural coefficient of transmission (Lecher) lines representing the electromagnetic oscillator in an atom [19] and Z is atomic number. c. This formula is derived in [30] . d. The difference disappears if true

4. Conclusions

With the current measurement results and with the appropriate theory, Duane- Hunt law which includes Planck’s h has been tested. Using 120 measurements in the range of 13.6 eV to 204.4 keV, i.e., in the range 1:15000, we conclude that Planck’s h is not constant. The results presented here confirm that Planck’s h is approximately constant in the energy range from a few eV, but for energy over a dozen keV h becomes significantly smaller and decreases to zero. That conclusion has been confirmed by statistical analysis of old measurement results from a century ago as well. So far, there was no suitable theory that could explain it, but now this theory exists and it is in accordance with both the old and the new measurements. With this theory it is possible to determine some phenomena in the nucleus of the atom. This theory also shows that the maximum possible atomic number Z is equal to the integer of 2

Further work in this area should include the study of possible stable states of atoms in states below the ground state with the expectation, in addition to the neutron and hyperons, some other particles could be found.

In this article, the voltage to 204.4 kV (Z = 110, darmstadtium) has been covered. The future research should broaden that range to 511 kV. In that process not only the voltage, but also corresponding frequency should be measured.

This article explains the continuous spectrum of bremsstrahlung. The formula for calculating the frequency of this radiation has been shown.

The work is based on the use of Maxwell’s equations and Einstein’s theory of relativity and the use of real oscillators, instead of Planck’s virtual oscillators. The quantization is only a consequence of harmonizing two continuous processes in the atom: the propagation of electromagnetic energy and the circular motion of electrons [18] [24] .

Acknowledgements

The author thanks to Ms. Srebrenka Ursić and Mr. Damir Vuk,

www.systemcom.hr, for useful discussions, to Mr. Branko Balon for the useful discussions, too, to Mr. Velibor Ravlić and Mr. Zlatko A. Voloder for encouragement in the writing this article and for expressing great expectations in benefits of using structural constants s0 instead of Planck’s h, then to Prvomajska TZR, Ltd., Zagreb, Croatia, www.prvomajska-tzr.hr, and to Drives-Control, Ltd., Zagreb, Croatia, www.drivesc.com, for logistic support.

Cite this paper

Perkovac, M. (2017) Planck’s h and Structural Constant s0. Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 425-438. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.83027

References

- 1. Millikan, R.A. (1916) Physical Review, 7, 355-388.

http://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.7.355

https://doi.org/10.1103/physrev.7.355 - 2. Bellotti, G. (2009) Physics Essays, 22, 268-287.

https://doi.org/10.4006/1.3141024 - 3. Bellotti, G. (2011) Physics Essays, 24, 364-378.

https://doi.org/10.4006/1.3601519 - 4. Bellotti, G. (2012) Applied Physics Research, 4, 141-151.

https://doi.org/10.5539/apr.v4n3p141

http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/apr/article/view/19256 - 5. Bellotti, G. (2012) Advances in Natural Science, 5, 7-11.

http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/ans/article/view/3126DOI:10.3968/j.ans.1715787020120504.2014 - 6. Lipovka, A. (2014) Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 2, 61-67.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jamp.2014.25009 - 7. Lipovka, A. and Cardenas, I.A. (2015) Duane—Hunt Relation Improved. Cornell University, 101-108.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.08783 - 8. Lipovka, A.A. and Cardenas, I.A. (2016) Variation of the Fine Structure Constant. Cornell University, 1-9.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.04593v1 - 9. Suchard, E.H. (2014) Physical Science International Journal, 7, 152-185.

http://sciencedomain.org/abstract/9858 - 10. Duane, W. and Hunt, F.L (1915) Physical Review, 6, 166-172.

http://link.aps.org/abstract/PR/v6/p166

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.6.166 - 11. Webster, D.L. (1916) Physical Review, 7, 599-613.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.7.599 - 12. Webster, D.L. and Clark, H. (1917) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 3, 181-185.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.3.3.181 - 13. Kulenkampff, H. (1922) On Thecontinuous X-Rayspectrum [über das Kontinuierliche Röntgenspektrum]. PhD Thesis, Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Munich.

- 14. Geiger, H. And Karl, S. (1926) Handbuch der Physik, Elementare Einheit und Ihre Messung. Verlag von Julius Springer, Berlin.

- 15. Eucken, A., Lummer, O. And Waetzmann, E. (1929) Müller-Pouillets, Lehrbuch der Physik, Band II: Lehre von der strahlenden Energie (Optik). 11th Edition, Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn Akt. Ges., Braunschweig.

- 16. Geiger, H. And Karl, S. (1933) Handbuch der Physik, Band XXIII/1, Quantenhafte Ausstrahlung. Second Edition, Verlag von Julius Springer, Berlin.

- 17. DuMond, J.W.M. (1939) Physical Review, 56, 153-164.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.56.153 - 18. Perkovac, M. (2002) Physics Essays, 15, 41-60.

https://doi.org/10.4006/1.3025509

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/pe/pe/2002/00000015/00000001/art00004

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239010583_Quantization_in_Classical_Electrodynamics - 19. Perkovac, M. (2003) Physics Essays, 16, 162-173.

https://doi.org/10.4006/1.3025572

http://physicsessays.org/browse-journal-2/product/993-2-milan-perkovac-absorption-and-emission-of-radiation-by-an-atomic-oscillator.html

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229020939_Absorption_and_Emission_of_Radiation_by_an_Atomic_Oscillator - 20. Perkovac, M. (2010) Statistical Test of Duane-Hunt’s Law and Its Comparison with an Alternative Law. Cornell University, 1-12.

http://arxiv.org/abs/1010.6083

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286623994_Statistical_Test_of_Duane-Hunts_Law_and_Its_Comparison_with_an_Alternative_Law - 21. Perkovac, M. (2012) Maxwell’s Equations for Nanotechnology. 2012 Proceedings of the 35th International Convention MIPRO, Opatija, 21-25 May 2012, 429-436.

http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6240683/ - 22. Perkovac, M. (2013) Journal of Modern Physics, 4, 899-903.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2013.47121 - 23. Perkovac, M. (2014) Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 2, 11-21.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jamp.2014.23002 - 24. Perkovac, M. (2015) The Structural Constant of an Atom as the Basis of Some Known Physical Constants. Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Physics, Simulation and Computers, Vienna, 15-17 March 2015, 92-102.

http://www.inase.org/library/2015/vienna/bypaper/APNE/APNE-14.pdf - 25. Kramida, A., Ralchenko, Y., Reader, J. and NIST ASD Team (2014) NIST Atomic Spectra Database (Ver. 5.2). National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg.

http://physics.nist.gov/asd - 26. Giancoli, D.C. (1988) Physics for Scientist and Engineers. 2nd Edition, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

- 27. Matveev, A.N. (1989) Mechanics and Theory of Relativity. Mir Publishers, Moscow.

- 28. Boscovich, R.J. (1763) Theoria Philosophiae Naturalis Redacta ad Unicum Legem Virum in Natura Existendum. Ex TypogrphiaRemondiniana, Venice.

- 29. Yavorsky, B. and Detlaf, A. (1977) Handbook of Physics. Mir Publishers, Moscow.

- 30. Perkovac, M. (2016) Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 4, 1899-1905.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jamp.2016.410192