Psychology

Vol.06 No.06(2015), Article ID:56263,17 pages

10.4236/psych.2015.66072

Ownership or Taking Action: Which Is More Important for Happiness?

Kohji Hayase1, Mitsuhiro Ura2

1Graduate School of Integrated Arts and Sciences, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan

2Faculty of Psychology, Otemon University, Osaka, Japan

Email: hayasekoj@hiroshima-u.ac.jp

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 28 February 2015; accepted 11 May 2015; published 13 May 2015

ABSTRACT

In two studies (2010 and 2011), more than 2000 respondents living in Japan were asked whether they gained more happiness from ownership or from taking action. In the 2010 study, many more individuals preferred taking action to ownership; this preference was greater in women than in men and in older people than in younger people. Reasons for this preference were plainly expressed in respondents’ free writing, and a categorical distinction between ownership and taking action was readily recognized and widely shared. Social desirability concerns probably did not play a role in responses. In the 2011 study, many individuals valued action more than ownership as like as the 2010 study. The preference for taking action over ownership was greater in women than in men, in older people than in younger people, and in people with higher levels of education than in people with lower levels of education. There was no relationship with annual income. The correlations with gender and level of education were similar to results of comparable studies con- ducted in the USA, although in the US studies, experiential purchases were evaluated, rather than taking action; however, the correlation with age was uncertain in the US studies. Further studies with US respondents will be necessary to examine this correlation. Possible reasons why many more people preferred happiness gained from taking action to happiness experienced from ownership were discussed.

Keywords:

Ownership, Taking Action, More Important for Happiness

1. Introduction

Forty years ago, John Lennon sang, “Imagine no possessions, I wonder if you can”. The concept of possession itself is interesting to consider, and investigate, and debate (Curchin, 2007) . A recent report explained happiness and well-being as agential flourishing (Raibley, 2012) . Possession (ownership) and taking action are concepts that contrast with each other, since the former represents stasis or little movement, and the latter is dynamic and movement itself. Thus, we have arrived at a significant question, psychologically and philosophically: Which is more important to achieve happiness, ownership (possession) or taking action? There is little research about the preference for ownership or taking action in relation to happiness. In this paper, we examine the happiness that people feel from possession or ownership in comparison to the happiness they achieve as a result of taking ac- tion. The purpose of this paper is to investigate Japanese people’s preference for ownership (possession) or tak- ing action, to evaluate the correlations of this preference with gender, age, level of education, and annual income, and to discuss reasons for people’s preference.

1.1. Relation between the Feeling of Happiness and Material Ownership (Possession)

It is sometimes assumed that material ownership (possession) disrupts people’s feelings of happiness. Some researchers criticized people in industrialized societies for favoring a “joyless economy” and “having” instead of enjoyment, “being” and self-actualization (Scitovsky, 1976; Fromm, 1976) . Social scientific study seems to back up the assumptions of these researchers, for example, that people who think buying things and acquiring material possessions give them a lot of pleasure report lower levels of happiness than people who do not do so (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996; Belk, 1985, 1988; Richins & Dawson, 1992; Nickerson et al., 2007; Howell & Hill, 2009; Xiao & Li, 2011; Welsch & Kühling, 2011; del Mar Salinas-Jiménez, Artés, & Salinas-Jiménez, 2011; Hudders, & Pandelaere, M., 2012; Howell et al., 2012). Frank (1999) found that across-the-board “increases in our stocks of material goods produced virtually no measurable gains in our psychological or physical well-being. Bigger houses and faster cars, it seems, don’t make us any happier” (p. 6). Delhey (2010) discussed theories of the post-materialization of happiness. Self-determination theory provides another perspective in which paying attention to superficial rewards prevents to self-actualization and disturbs personal integration (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Kasser, 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Dunn et al. (2008) indicated that prosocial spending contributed to life satisfaction, and Xiao & Li (2011) also suggested that happiness was associated with prosocial spending.

1.2. Preference for Ownership (Possession) or Taking Action for the Feeling of Happiness

Some research has investigated the preference for possession (material purchases) or experience (experiential purchases) in feeling happy (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003; Van Boven et al., 2010; Carter & Gilovich, 2010, 2012; Rosenzweig & Gilovich, 2012; Howell et al., 2012). Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) examined whether experiential purchases made people happier than material purchases. They reported that respondents felt much happier from their experiential purchases (57%) than from their material purchases (34%). They also reported correlations between the preference for material purchases or experiential purchases and gender, age, level of education, and annual income in the USA (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003; Witter et al., 1984) , although the significance levels of the correlations were not reported.

On the other hand, there is little research about the preference for ownership (possession) or taking action in relation to happiness. One reason could be the difficulty in differentiating the terms “taking action”, and “experience”. One possible difference between the terms action and experience might be that people valued taking action for its achievement value, in addition to its experiential value (Nozick, 1974) . According to Webster’s New World Dictionary, action is the doing of something and/or state of being in motion or of working, whereas experience is the act of living through an event or events; personal involvement in or observation of events as they occur. These meanings are similar in Japanese. Taking action might have broader meaning beyond its experiential value (i.e., experiencing an event or events), such as work or achievement of value, and/or volunteering and making charitable contributions. Moreover, happiness from taking action is to some extent different from happiness from experience or experiential purchase, in accordance with the distinction between episodic happiness and well-being (Raibley, 2012) , since experience or experiential purchase is related or connected to an episode, an event, or events. We investigated the preference for ownership (possession) or taking action, in relation to hap- piness, considering that the term taking action included the term experience.

We think that ownership is not only related to purchasing behavior, but also related to the monopolization of materials, which is close to being selfish. Psychological study of monopolization materials (Why do some people like to monopolize materials instead of freely transferring them to others?) is a very important and useful topic for the psychology of happiness and/or peace. When we look deeply into the question of ownership, we can find very broad and meaningful aspects in ownership, as like as in taking action. We think that taking action and ownership are also comparable in their broad meanings. Then, we carried out the research about the preference for ownership (possession) or taking action in relation to happiness.

Many substantial cultural variations have been identified between independent (e.g., Euro-American) and interdependent (e.g., Asian) cultures (Uchida et al., 2004; Uchida et al., 2008; Uchida et al., 2009) . Investigating people’s preferences for ownership (possession) versus taking action in an interdependent Asian country is sig- nificant, in order to compare such findings with findings from independent countries such as the US. In the present study, we examine feelings of happiness in Japan, as a representative of an interdependent Asian culture (Hofstede et al., 2010) . We evaluate correlations of the preference for ownership (possession) or taking action with gender, age, level of education, and annual income to reveal many social, physical and psychological cir- cumstances, since there is no such study at present. We performed a nationwide Internet survey in Japan to in- vestigate these correlations.

In Study 1, we investigated the more important contributor to happiness: 1) ownership, or 2) taking action. We asked participants the question, “Which do you attach more importance to, the feeling of happiness from ownership, or the feeling of happiness from taking action?” Participants responded by selecting one of the two alternatives. Then, in response to a question asking their reasons for the selection, participants freely, but concretely, described their reasons. We also assessed participants’ age and gender. In Study 2, we asked participants three types of questions about their preference for ownership, or for taking action, by using questions that dif- fered because they included, or did not include, concrete examples. The response type for these questions also varied, with 2 to 6 alternative response choices. In Study 2, we also assessed participants’ age, gender, education, and income.

2. Study 1 (2010)

2.1. Method

A total of 1062 respondents participated (514 men and 548 women; average age 44.6 years, standard deviation 14.4).

Respondents were registered with a social survey company, INTAGE Inc., which has over one million respondents all over Japan. Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the respondents. Each year within each age decade was represented by a group of respondents (e.g., for men, 15 20-year-olds, 4 21-year olds, 6 22-year-olds, 10 23-year-olds, 7 24-year-olds, 16 25-year-olds, and so on).

There was no correlation between gender and age, and the demographic distribution of the respondents was statistically ideal for the study of correlations of factors with gender and age.

2.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire included a brief demographic survey that asked the respondent’s gender and age. There were also two questions, one a quantitative assessment and the other a qualitative assessment. The quantitative assess- ment about the feeling of happiness from ownership or from taking action was as follows.

The “feeling of happiness from ownership” is the conscious happiness that people get when acquiring something as a possession. The “feeling of happiness from taking action” is the conscious happiness that people get from doing something or experiencing something. At present, which do you attach more importance to, the feeling of happiness from ownership or the feeling of happiness from taking action?

Through this question, we evaluated peoples’ subjective attitudes toward ownership and taking action and assessed their preferences for achieving happiness by these means. We have indicated that the exact Japanese words used for ownership is “motsu” and/or “syoyusuru”, and that the exact Japanese words used for taking action is “okonau” and/or “kohdohsuru” for discussion of the differences in connotation between the meanings of word. Respondents answered by selecting one of the two options (The feeling of happiness from ownership, or The feeling of happiness from taking action). The qualitative question asked respondents to write freely but con- cretely about the reasons for their preference.

2.3. Procedures

The participants were randomly selected from the respondents of INTAGE Inc., and the questionnaire was sent

Table 1. Frequency distributions of responses to Study 1 in 2010 number of respondents that selected the response (numbers in parentheses are its percentage) words (Score 1 and 2) were not written in the questionnaire.

to them through the Internet. The respondents completed the questionnaire some time from the 15th to the19th of January 2010. The respondents received compensation for participating in the survey. All respondents provided informed consent.

Sampling bias of respondents is rather small, since INTAGE Inc. rigorously performs “Identity verification” and “Maintenance after respondent registration”. For example, “Identity verification” is that INTAGE Inc. conducts individual identification by sending a parcel to the respondent’s registered address to verify the individual and their location, and also, INTAGE Inc. prevents double respondent registration by checking duplicate email addresses. “Maintenance after respondent registration” is that INTAGE Inc. conducts quality survey and by checking the cookies stored on the respondent’s computers, when judged that the same PC (computer) is being used by the same person to answer several questionnaires, the respondent is detected and recognized as “inadequate respondent”, thus suspending sending the questionnaire to that respondent.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 1 shows frequency distributions of answers and cross tabulations of scores for each item by gender and age group in study 1. Respondents preferred feelings of happiness from taking action (765: 411 women, 354 men) to feelings of happiness from ownership (297: 137 women, 160 men). This tendency for people in Japan was similar to that for people in the US (Van Boven & Gilovich 2003; Carter & Gilovich, 2010, 2012; Rosenzweig & Gilovich, 2012; Howell et al., 2012) , although the term experience, not taking action, was used in the US study. As mentioned above, there is a difference between taking action and experience or experiential pur- chase. Moreover, while experience or experiential purchase is considered to be related to episodic happiness, as Raibley (2012) has suggested, taking action is closely connected to agential flourishing. Since agential flourishing is different from episodic happiness (Raibley 2012) , taking action and experience or experiential purchase differs to some extent with regard to happiness. Our study is fundamentally different from the study by Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) , because our study is asking a very different question from Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) . However, we cited the study by Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) , because it has certain similarities to our study, such as the effects of attributes. We have discussed their study in relation to ours with regard to aspects such as the effects of attributes on preference.

The path coefficients (standardized partial regression coefficients) between preference for taking action over ownership and gender (men to women) from the above results was +0.065 (p = 0.03). Male and Female gender were dummy coded as 1 and 2, respectively. Ownership and taking action were dummy coded as 1 and 2, respectively. Although dichotomous variables are usually considered to be a nominal scales, or categorical variables, they also fit an interval scales, because there are only two numbers (namely 1 and 2). If there were three numbers, such as 1, 2 and 3, similar to a nominal scale, it would be important to state that it is not an interval scale. However, if there are only two numbers, such as 1 and 2, similar to a nominal scale, mathematically, there is no problem in obtaining averages and/or correlation coefficients by regression analysis and/or path analysis.

The obtained path coefficient (+0.065) indicates that women were more likely than men to prefer feelings of happiness from taking action over those from ownership, while both valued taking action more than ownership. This result is also similar to the results of Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) for US respondents, “whereas the term experience was used in US”. We think that our research is fundamentally different from the study by Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) . Therefore, we compared our results and theirs only with regard to the effect of attributes on preference. We will discuss the correlation of gender with the preference for ownership or taking action in more detail in Study 2. On the other hand, path coefficient between the preference for taking action over ownership and age (young to old) was +0.197 (p < 0.001), indicating that older people, compared to younger people, are more likely to prefer feelings of happiness from taking action over those from ownership, although both valued taking action more than ownership. This is the first demonstration of a correlation between age and preference for taking action or ownership. Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) found a somewhat different tendency in their US study; we will discuss this in detail in Study 2.

This research was intended to discover people’s preference for taking action versus ownership (possession) for the feeling of happiness. In the question, we did not mention concrete examples, such as owning a TV or a car for ownership or driving or working for action. This is because we expected to find a categorical distinction between ownership (possession) and taking action that is recognized and widely shared by people. We will return to this distinction in Study 2.

It may be difficult to classify certain items as being either possessions or actions. But, as Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) point out, at dusk it can be difficult to discern whether it is really day or night, but this does not undermine the utility of the general distinction between night and day. Consider the example of buying art supplies. On the one hand, one may simply enjoy owning nice art supplies, but on the other hand, the very nature of art supplies suggests the action of artistic expression and the happiness that flows from that action. Similarly, while some interpretive difficulties may exist between ownership (possession) and taking action (experience), they do not render the distinction meaningless.

It may be possible to rely on people’s intentions to help assign a concrete item to one category or the other. If a person intends to acquire a material good with the aim of using it to perform a valuable action, then it may fall in the action-taking category. On the other hand, if a person intends to acquire the same good to simply enjoy owning it, it falls into the ownership (possession) category. For example, consider the acquisition of an antique book. A scholar might acquire the book with the intention of using it for research (action), while a collector might acquire the very same book simply to enjoy owning it (possession).

Although our question partly resemble to that used in previous research (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003; Carter & Gilovich, 2010, 2012) , our choice of words differed to some extent: ownership and taking action in our research, and possessions and experiences in theirs. One possible difference between the terms action and experience might be that people might value taking action for its achievement value in addition to its experiential value (Nozick, 1974) . Another difference between our study and theirs is as follows. In past research, such as Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) , each type of purchase (experience vs. possession) was rated on a separate scale. However, we consider that this study is fundamentally different from the study by Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) . In this study, it was considered appropriate to use ratings that essentially involved forced choices on bipolar scales. Our question is useful to distinguish between ownership (possession) and taking action, and the distinction between the feeling of happiness from ownership (possession) and the feeling of happiness from taking action appears to be recognizable for people. Our finding that preference for taking action over ownership (possession) was significantly correlated with gender and age can be taken as evidence that the categorical dis- tinction between ownership (possession) and taking action is readily recognized, sufficiently comparable and widely shared by people.

In the free writing response section of our questionnaire, the respondents expressed many reasons for their preferences. Examples of a preference for ownership (possession) over taking action included “I like things with shape,” “I would like to be surrounded by something I want to have,” and so on. On the other hand, examples of the reasons given for a preference for taking action over ownership included “I can enjoy more when I take action,” “While the feeling of happiness from ownership belongs only to a single person, we can enjoy the feeling of happiness from taking action with many people around us,” “Although the feeling of happiness from ownership fades at some time, happiness from taking action produces a variety of fresh impressions in our lives,” “I feel happiness from the use of material goods, not from the ownership of material goods,” and so on. Space constraints preclude presenting more than a small selection of the free writing responses; although 73 respondents wrote answers such as “no particular reason,” “somehow,” or “for some reason or other,” more than 90% of the respondents wrote answers that presented a clear reason for preferring the feeling of happiness from ownership or from taking action, and each reason seems persuasive. Since most of their reasons were written plainly, there is little possibility that our results are an artifact of social desirability concerns.

4. Study 2 (2011)

We conducted an additional study, Study 2, to extend Study 1 in the following five ways.

1) To change the type of question from two to six alternatives.

2) To examine the frequency distributions of the six alternatives.

3) To include three types of questions about preference for ownership or taking action whose wordings differ, and to include questions that do and do not include concrete examples.

4) To confirm whether or not a latent variable is extracted as a significant factor from the three questions.

5) To examine level of education and annual income as additional attributes.

The six alternative results obtained by using a more precise analysis facilitate deeper discussions and lead to clearer results. Moreover, asking three questions further clarifies the preference factor by showing a higher Cronbach’s alpha for the latent variable. Therefore, we consider that Study 2 is highly significant and well de- signed.

4.1. Method

A total of 1110 respondents participated (559 women, 551 men; mean age 44.7 years, standard deviation 13.7).

As in Study 1, respondents were registered with a social survey company, INTAGE Inc. Table 2 shows the demographic profile of the respondents. Each year within each age decade was represented by a group of respondents (e.g., for women, 9 20-year-olds, 8 21-year olds, 10 22-year-olds, and so on). As in Study 1, there was no correlation between gender and age, and the demographic distribution of the respondents was statistically ideal for the study of correlations of factors with gender and age.

4.2. Measurement of Variables

The questionnaire included a brief demographic survey asking gender Q1 and age Q2. Respondents selected one of the following options to indicate their individual annual income Q3: (1) Less than one million (Japanese) yen, (2) 1 - 2 million yen, (3) 2 - 3 million yen, (4)…(9), (10) 9 - 10 million yen, (11) 10 - 12 million yen, (12) 12 - 15 million yen, (13) 15 - 20 million yen, (14) 20 million yen or more.

Respondents selected one of the following options to indicate their level of education Q4: (1) Graduated from primary school, (2) Graduated from junior high school, (3) Graduated from high school or vocational school, (4) Graduated from specialized vocational school or junior college, (5) Graduated from university, (6) Graduated from graduate school.

Table 2. Cross tabulation scores by gender and age group. Frequency distributions of responses to Q5 of Study 2 in 2011; Number of respondents that selected the response (numbers in parentheses are its percentage); words (Score 1 - 6) were not written in the questionnaire.

Three questions investigated preference for feeling happiness from ownership or from taking action:

Q5: The “feeling of happiness from ownership” is the conscious happiness that people get when acquiring something. The “feeling of happiness from taking action” is the conscious happiness that people get from having done something. At present, which do you attach more importance to: the “feeling of happiness from ownership” or the “feeling of happiness from taking action”? (1) Much more “feeling of happiness from ownership”, (2) “Feeling of happiness from ownership”, (3) Somewhat “feeling of happiness from ownership”, (4) Somewhat “feeling of happiness from taking action”, (5) “Feeling of happiness from taking action”, (6) Much more “feeling of happiness from taking action”.

Q18: Do you feel more enjoyment and/or happiness when you have taken ownership of something or when you are doing something? (1) Much more when doing something, (2) When doing something, (3) Somewhat when doing something, (4) Somewhat when taking ownership of something, (5) When taking ownership of something, (6) Much more when taking ownership of something.

Q29: The “joy of ownership” is the feeling of happiness that people get when acquiring things such as possessions, clothing, vehicles, homes, and so on. The “joy of taking action” is the feeling of happiness that people get from having taken an action such as having made something, having used something, having had fun, or having worked. At present, which do you attach more importance to: the “joy of ownership” or the “joy of taking action”? (1) Much more “joy of taking action”, (2) “Joy of taking action”, (3) Somewhat “joy of taking action”, (4) Somewhat “joy of ownership”, (5) “Joy of ownership”, (6) Much more “joy of ownership”.

The six alternatives were shown in the above order. Items numbered (1) - (6) are response items. However, these numbers were not shown in the questionnaire, in order to avoid pre-evaluation of the responses by respondents. Higher scores for Q5 indicate a preference for taking action, and higher scores for Q18 and Q29 indicate a preference for ownership. As like as in Study 1, we asked people fundamentally their subjective attitudes toward ownership and taking action and assessed their preferences for achieving happiness by these means.

In Study 1, we did not include any examples for the survey question. By contrast, in Study 2, we provided concrete examples in Q29 (acquiring possessions, clothing, vehicles, and homes, and having made something, having used something, having had fun, and having worked), which may have helped the respondents’ deliberations. On the other hand, concrete examples were not provided for Q5 and Q18. This is because we tried to examine whether the categorical distinction between ownership and taking action is recognized and widely shared by people regardless of the presence or absence of concrete examples.

Raibly (2012) discussed episodic happiness and distinguished it from well-being. Now is the time to rethink and re-discuss “What is happiness?” Therefore, we did not assess the present level of happiness, which is very similar to episodic happiness. In order to further investigate the “quest for happiness” (not episodic happiness) and/or kinds and qualities of happiness, we asked people whether they preferred happiness from ownership, or taking action. This method is our original method of investigating real hapiness, as opposed to episodic happiness. We believe that this method will be highly useful for the clarification of real happiness.

4.3. Procedures

As in Study 1, the participants were randomly selected from the respondents of INTAGE Inc., and the questionnaires were sent to them through the Internet. The respondents completed the questionnaires some time from the 4th to the 8th of February 2011. The respondents received compensation for participating in the survey. All respondents provided informed consent.

Sampling bias of respondents is rather small, since INTAGE Inc. rigorously performs “Identity verification” and “Maintenance after respondent registration”, which are already explained in Study 1.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

We selected path analysis (SEM: Structural Equation Modeling) rather than multiple regression analysis for the followings reasons. In the case of analyzing three variables A, B and C, in which A predicts B and B predicts C, it is necessary to consider a model of chaining prediction, which would allow us to discuss different variables and evaluate the appropriateness of the model by path analysis (SEM). However, we cannot analyze such a model by using multiple regression analysis, because in a multiple regression analysis, each A, B or C can be only an independent, or a dependent variable. Moreover, the set for path analysis (SEM) totally includes the set for multiple regression analysis. Therefore, we selected path analysis (SEM) over multiple regression analysis.

4.5. Results and Discussion

We used exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses to demonstrate the statistical validity of the distinction between the feeling of happiness from ownership (possession) and feeling of happiness from taking action.

By exploratory factor analysis, questions Q5, Q18, and Q29 were extracted as a factor. Tables 2-4 show frequency distributions of answers for Q5, Q18 and Q29 and cross tabulations of scores for each item by gender and age group in Study 2. The averages and 95% confidence intervals of the three questions were: Q5: 3.674, 3.6058 - 3.743 (higher than 3.5), Q18 (reversed) = Q18rv: 3.936, 3.877 - 3.994 (higher than 3.5), and Q29 (reversed) = Q29rv: 4.037, 3.976 - 4.098 (higher than 3.5). Having a high confidence average that is higher than 3.5 in question Q5 means that respondents preferred “feelings of happiness from taking action” over “feelings of happiness from ownership”. A high confidence average that is higher than 3.5 in questions Q18rv and Q29rv means that respondents preferred “doing something” over “taking ownership of something” and “joy of taking action” over “joy of ownership”.

More Japanese people preferred the feeling of happiness from taking action, a tendency similar to that found in Study 1. Each of the three questions was asked using different wording. Question Q5 was asked abstractly, with no concrete examples. Question Q18 was asked more concretely, in terms of doing versus taking ownership, but still with no examples. Finally, question Q29 provided actual examples of material goods, such as possessions, clothing, vehicles, and homes for ownership, and having made something, having used something, having

Table 3. Cross tabulation scores by gender and age group. Frequency distributions of responses to Q18 of Study 2 in 2011; Number of respondents that selected the response (numbers in parentheses are its percentage); words (Score 1 - 6) were not written in the questionnaire.

had fun, or having worked for taking action. Despite these differences of wording, responses to all the three questions exhibited the same tendency of showing preference for taking action over ownership. This finding could also be used to define the term “taking action”, since different terms, such as “taking action” in Q5, as “doing something” in Q18 and as “having made something, having used something, having had fun, or having worked” in Q29 were used. Therefore, it is clear that people have a concrete concept regarding the term “taking action”. Above results provide evidence for the existence of a categorical distinction between ownership and taking action that is recognized and widely shared by people regardless of the presence or absence of concrete examples.

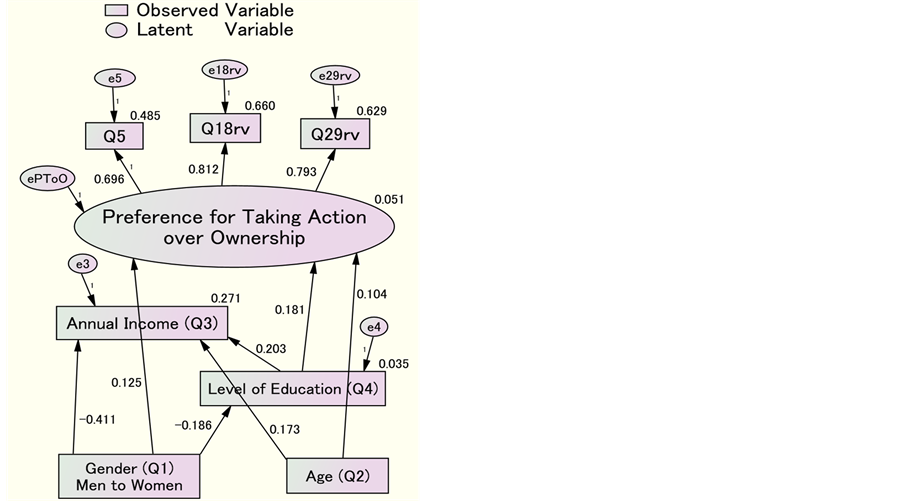

Obtained Cronbach’s alpha for Q5, Q18rv and Q29rv was 0.810. Cronbach’s alpha in this study, 0.810, was sufficiently high. Moreover, Q5, Q18rv and Q29rv could be treated as items that measure a single factor that can be summed as a single scale. It can be confidently stated that these three questions (observed variables) tracked a latent variable as a factor. We named this latent factor “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)” for Q5, Q18rv and Q29rv, because higher response numbers indicated preference for taking action. A confirmatory factor analysis of the factor and structural equation modeling of the latent variables (SEM/LV) were carried out (by Amos19). The analysis included the attributes of gender, age, level of education, and annual income, which predict the factor, as illustrated in Figure 1.

In this path analysis, the relationship with predictivity (not causality) was as follows. We assumed that gender, age, level of education and annual income might predict the preference in Figure 1. Gender and age are basic predictors that are not predicted by anything else and it is reasonable to assume that gender and age might pre-

Table 4. Cross tabulation scores by gender and age group. Frequency distributions of responses to Q29 of Study 2 in 2011; Number of respondents that selected the response (numbers in parentheses are its percentage); words (Score 1 - 6) were not written in the questionnaire.

dict the level of education and annual income. On the other hand, we assumed that the level of education might predict annual income, because the mean level of education is decided at a younger age, around or below twenty years of age, whereas mean annual income from an occupation is decided at a rather older age. Therefore, we assumed that level of education might predict annual income.

In Figure 1, only significant paths are drawn (p < 0.001), and the factor is the latent variable “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)”, and attributes are observed variables as predictors. Since RMSEA was 0.008 (RMSEA ≤ 0.06 or less; Hu & Bentler, 1999 ), CFI was 1.000 and factor loadings were 0.696 for Q5 (p < 0.001), 0.812 for Q18rv (p < 0.001), and 0.793 for Q29rv (p < 0.001), goodness of fit for SEM/LV was acceptable. The model fit was good, because direct paths connected nearly all variables. We clarified the direction of scoring to make the nature of associations between the variables clearer. In Table 5, we have reported more detailed information, such as the matrix of correlations among all variables along with their means, SDs, correlation coefficients and covariance. The significance tests for the paths are based on the standardized coefficients. We also added R2 for each dependent variable in Figure 1.

Wang & Wang (2012) have stated the following in pages 17 and 18 in their book: Structural Equation Modeling (Applications Using Mplus).

The chi square statistic has some explicit limitations. First, the chi-square is defined as N-1 times the fitting function; thus, it is highly sensitive to sample size. The larger the sample size, the more likely it is to reject the model, thus the more likely becomes Type I errors (rejecting the correct hypothesis). The probability of rejecting a model would substantially increase when the sample size increases, even though differences between observed and model estimated variance/covariance matrices are trivial.

Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis of “Preference for taking action over ownership” and SEM/LV including the four attributes (gender, age, level of education and annual income) that predicted the factor. Correlation coefficients between “Preference for taking action over ownership” and the four attributes are written only for paths with p < 0.001. The questions were as follows: [Q1]: Gender (Men to Women); [Q2]: Age; [Q3]: Annual income; [Q4]: Level of education, [Q5] indicated that respondents’ preferences were for “feelings of happiness from taking action” over “feelings of happiness from ownership”. [Q18rv]: Response numbers were reversed from [Q18], such that respondents’ preferences were for “doing something” over “taking ownership of something”, because higher response numbers indicated preference for taking action. [Q29rv]: Response numbers were reversed from [Q29], such that respondents’ preferences were for “joy of taking action” over “joy of ownership”, because higher response numbers indicated preference for taking action. Factor loadings for [Q5], [18rv] and [Q29rv] (all p < 0.001) are indicated along the paths. R2 was indicated on shoulder of each dependent variable.

Since the sample size of our study was over 1000 participants, which is a considerably large sample, it would be inappropriate to use the chi-square. According to the Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics, Cramer’s V is closely related to the chi-square. Therefore, it would also be inappropriate to use Cramer’s V in this study.

We want to mention followings regarding the weighted sum of Q5, Q18rv, and Q29rv. Since observational variable (each Q5, Q18rv, and Q29rv) is equal to true value + errors, sum of the errors are also represented in the weighted sum. Therefore, weighted sum errors do not decrease, and might increase by addition, which is a known as, “rarefied”, or as a “thinner”, which is well known to researchers. It has often observed from data that absolute values of correlation coefficients between observed variables are smaller than absolute values of correlation coefficients between latent factors. This is regarded as a manifestation of “rarefication” or “thinning”. “Rarefication” or “thinning” means that correlations between observed variables that are additions of errors to true values become lower than correlations between true values that are latent factors, without the addition of errors.

As a result, the absolute value of the correlation coefficient between the weighted sums would be lower than that of the correlation coefficient between latent variables obtained by factor analysis. On the other hand, the latent variable in SEM (path analysis) is expected to be rather closer to the true value than the weighted sum, if Cronbach’s alpha is higher and number of observational variables is larger. RMSEA (lower than 0.06) is useful (Hu & Bentler, 1999) for evaluating the goodness of fit for modeling, therefore, we adopted the SEM and attached more importance to RMSEA.

4.6. Demographic Correlations

Figure 1 demonstrates the psychological significance of the correlations between “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)” with gender, age, level of education, and annual income in Japan. Correlation coefficients of “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)” with gender, age, level of education, and annual income are summarized in Table 6, together with comparable correlations from Study 1.

4.7. Correlation of Gender with “Preference for Taking Action over Ownership (Possession)”

The path coefficient between gender (men to women) and “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)” was +0.125 (p < 0.001), indicating that women attached more importance to the feeling of happiness from taking action than did men, while both valued taking action more than ownership. This result is similar to the result of Study 1. We compared effects of attributes on the preference between the study of Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) and our study. In the study of Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) in the USA, 51% (62%) of men (women) indicated that their experiential purchase made them happier than their material purchase, with 38% (30%) indicating the reverse. Our questions and those of Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) were worded somewhat differently (taking action and ownership versus experiential and material purchases, respectively); however, the meanings largely corresponded, although taking action may be considered desirable for its achievement value

Table 5. Mean, standard deviation, correlation coefficient and covariance for Q1, Q2, Q4, Q3, Q5, Q18 and Q29 in Study 2 in 2011.

** p < 0.01.

Table 6. Correlation of the four attributes with “preference for taking action over ownership”.

***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05.

in addition to its experiential value. In the US results, women appeared more likely than men to attach more importance to experiential purchases than to material purchases. Although beta between gender and people’s preference for material or experiential purchases and significance level were not provided by Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) , our results are consistent with their finding of a correlation of gender with “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)”.

This provides evidence that the gender correlation may be similar in Japan and in the US, “where the term experience was used”. It would be valuable to investigate possible reasons why women, as compared to men, attach more importance to the feeling of happiness from taking action than from ownership.

4.8. Correlation of Age with “Preference for Taking Action over Ownership (Possession)”

In the SEM/LV in Figure 1, path coefficient between age and “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)” was +0.104 (p = 0.001). Older people, as compared to younger people, attached greater importance to feelings of happiness from taking action than to those from ownership (possession), although both valued taking action more than ownership. This is similar to the result of Study 1, but comparisons with the results of Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) are difficult. Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) stated that younger individuals were a bit more likely than elderly people to indicate that experiences made them happier. This appears to be the opposite of our results in Studies 1 and 2. However, in their results, 59% of 21 - 34 year olds, 58% of 35 - 54 year olds, and 49% of 55 - 69 year olds indicated that their experiential purchases made them happier than their material purchases, and 36%, 31%, and 38% indicated the reverse. Given such percentages, and the absence of reports of significance and beta values for age and preference for material or experiential purchases, it is difficult to conclude that younger individuals were more likely than elderly people to indicate that experiential purchases made them happier. Therefore, for U.S. respondents, the correlation of age with the feeling of happiness from experiential purchases versus material purchases remains unconfirmed.

On the other hand, the present study provides the first evidence that older people, compared to younger people, in Japan attach greater importance to taking action than to ownership; in other words, younger people value ownership relatively more compared to the amount that older people value it, although both valued taking action more than ownership. In future studies it will be necessary to investigate the correlation of age with the feeling of happiness from ownership (possession) or taking action in the U.S.A.

4.9. Correlation of Level of Education with “Preference for Taking Action over Ownership (Possession)”

In the SEM/LV in Figure 1, the path coefficient of level of education with “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)” was +0.181 (p < 0.001). In other words, people with higher levels of education attached more importance to feelings of happiness from taking action than did people with lower levels of education, although both valued taking action more than ownership. Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) observed that American respondents with the lowest levels of education (some high school or less) were slightly more likely to indicate that material possessions made them happier, whereas respondents with at least a high school degree were likely to indicate that experiences made them happier. Although the significance level and beta between levels of education and people’s preference for material over experiential purchases were not provided in the study of Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) , their results and those of the present study are likely consistent, “even though the term experience was used in the US”.

This provides evidence that education level affects the preference similarly in both Japan and the USA. It remains to be determined if and how more extensive study and/or greater opportunities for education, affects the belief that taking action is more important than ownership for happiness.

4.10. Correlation of Annual Income with “Preference for Taking Action over Ownership (Possession)”

In the SEM/LV in Figure 1, there was no significant correlation between annual income and “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)”. This result differs from the result of Van Boven & Gilovich (2003) for US respondents, for whom level of income was positively associated with the endorsement of experiential over material possessions; respondents with the lowest levels of income were equally likely to indicate that material or experiential purchases made them happier. It is possible that Americans with higher incomes feel happier from experience than people with lower incomes.

On the other hand, for Japanese respondents there was no significant correlation between annual income and the “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)”. Because Van Bowen and Gilovich (2003) pro- vided no statistical evidence, further research is required to investigate the correlation between annual income and “Preference for taking action over ownership (possession)” for US respondents and to clarify or confirm differences in the existing results for Japan and the US, “where the term experience was used”.

5. Taking Action over Ownership

Why do most people prefer taking action to ownership for achieving happiness?

The results of Carter & Gilovich (2010) suggest that experiential purchase decisions are easier to make and more conducive to well-being. Rosenzweig & Gilovich (2012) claim that people’s material purchase decisions are more likely to generate regrets of action (buyer’s remorse), and their experiential purchase decisions are more likely to lead to regrets of inaction (missed opportunities). It is possibly that people may be less satisfied with their material purchases because they are more possibly to ruminate about the material purchase decisions (buyer’s remorse). Howell et al. (2012) reported that non-materialistic values predicted a preference for experiential purchasing, leading to increased psychological need satisfaction, and, ultimately, increased subjective well-being. Life experiences become part of who we are. Carter & Gilovich (2012) noted that people tend to think of their experiential purchases as more connected to the self than their possessions. Knowing a person’s experiential purchases may yield greater insight into that person’s true self.

The free writing of the respondents in Study 1 provides insight on the preference for taking action over ownership. We identified four conspicuous themes, as listed in Table 7. These four themes were based on the number of responses that fell into each of the following categories: Theme 1, shortcoming of material possessions; Theme 2, merits of taking action; Theme 3, direct comparison (contrast) between ownership and taking action; and Theme 4, philosophically transcendent aspects of ownership or taking action.

Theme 1: People do not like something fleeting, untrue to the self, or unspiritual, gained through ownership.

Although material possessions are basically necessary to our lives, we cannot be satisfied only by possessions. Happiness from material possessions is fleeting because things are lost, decay, and cannot be taken when one dies. In contrast, the happiness from action is seen as being lasting because it improves the person and accomplishes things in the world that remain even after one’s death. To be happy, we do not need something that is not heartfelt, untrue to the self (Carter & Gilovich, 2012) , or unspiritual, which can be gained through ownership.

Theme 2: People prefer happiness from doing something valuable for and/or with other people.

People like to do something good or helpful for other people. People also enjoy doing something good with other people, friends, and/or family. These are two reasons why people prefer taking action to ownership. Doing something pleasurable with other people, especially with one’s intimates, is one of the happiest things in the

Table 7. Four main themes and examples of statements from respondents.

world for almost all people, as respondents mentioned in some of their statements and research has confirmed (Whitchurch et al., 2011; Canevell & Crocker, 2010; Murray et al., 2009; Diener & Seligman, 2002; Larson et al., 1986) . Theme 2 corresponds to Raibley’s (2012) observation that realization of one’s values through one’s own action may involve nurturing loved ones, protecting or safeguarding the things one cares about, or nourishing one’s personal relationships. People are generally happy to do something good for and/or with other people, acquaintances, friends, siblings, parents, children, spouses, and/or other intimates. People prefer happiness from taking action to ownership through doing something valuable to and/or with other people.

Theme 3: People pursue happiness in order to be unlimited, active, or more fully developed, rather than being limited, passive, or satiated.

Happiness from taking action and ownership are contrasted as follows. Happiness from taking action is unlimited and active, leads to development, and cannot be satiated. On the other hand, happiness from ownership is limited and passive, reaches an end point, and can be satiated. Since many respondents wrote statements similar to these, it appears that one of the reasons they prefer taking action over ownership is that they would like the pursuit of happiness to be unlimited, active, developmental, and insatiable rather than limited, passive, an end point, and satiable.

Theme 4: Materials are only entrusted to us by the earth.

From a philosophical perspective, one respondent transcendently expressed that we do not own material possessions. This sentence reminds us that there are fundamental philosophical questions about the nature of material ownership (Pendlebury et al., 2001; Uyl & Rasmussen, 2003; Taylor, 2005; Curchin, 2007; Brian, 2010; Ypi, 2011) . Consider the following scenario. There is a pencil thrown away in the box in a room. We suppose that only one person comes to the room and sees that there is a pencil. The person knows she does not own the pencil at the moment, but after she has found it, if she wishes to own it she will take it with her out of the room, and then she can think that she owns it. It can be said that she changed her mind from thinking that she does not own it to thinking that she does own it. The Japanese word Omoi means united. The original meaning of Omoi was “concern”, “consideration”, and the feeling and/or “minding”, among others. People use the word “Omoi” by saying, for example; she changed her Omoi from not owning it to owning it. On the other hand, if she does not want to own it, she would not take it with her. In this case, it can be said that she would not change her mind. If the word Omoi were to be used in this situation, we would usually say that she did not change her Omoi. Thus, ownership of something depends on whether one thinks that one possesses it or not, because there is no objective evidence of who owns it. Thus, with regard to material items, ownership depends just on people’s minds and/or imaginations, and does not depend on absolute criteria. In other word, ownership of something depends only on people’s Omoi. Early modern political philosophers such as John Locke have made similar arguments to show that there is no property in the state of nature (Locke, 1988 originally 1689) . Then, it may be said that any material item intrinsically does not belong to any person. A more detailed investigation about the question of material ownership should be carried out, since little practical psychological study of the question of material ownership has been conducted.

On the other hand, our bodies are directly attached to ourselves. Such conditions are thought to be evidence of ownership (Brian, 2010) ; however, some recent philosophical studies have argued that there is no self-owner- ship of one’s body, to say nothing of material ownership (Pendlebury et al., 2001; Uyl & Rasmussen, 2003; Taylor, 2005; Curchin, 2007; Ypi, 2011) . Further research is necessary to more fully address the question of self-ownership and no ownership both psychologically and philosophically. This is a profound question that re- mains to be answered.

Because more people preferred happiness from taking action to happiness from ownership in both Japan and the USA, we may be able to conclude that taking action, not ownership, is critical to being happy for human be- ings. Moreover, in order to be happy, we have to take into account the importance of “what we take action about”. In future research, it is necessary to study the kinds of actions that contribute to the happiness of human beings, experimentally, psychologically, practically, and philosophically. As John Lennon sang, “Imagine no possessions”; true happiness for human beings may be found and established within a world of “taking action” with “less ownership”.

6. Conclusion

In Japan, as in the US, more people preferred the feeling of happiness from taking action to that from ownership. While further investigation in other countries is necessary, it may be generally said that people usually become happier from taking action than from ownership. On the other hand, analysis of the correlations of the preference with the four demographic measures in our second study produced an inconsistent pattern for the two countries. Specifically, more importance was attached to taking action by both Japanese and American women than by men, and by people with higher levels of education than by those with lower levels. However, older people in Japan attached more importance to taking action than younger people, but this relationship remained unclear in US data. Finally, there was no significant correlation between annual income and the preference in Japan, whereas people of higher income in the US felt happier by experience or experiential purchase compared with people of lower income. Further investigation of correlations (with significant level) with the preference and gender, age, level of education, and annual income in the US will be necessary before further comparisons between Japan and the USA can be achieved.

Possible reasons for people’s preference for happiness from taking action rather than happiness from ownership may include the followings. First, to be happy, we need things that are more heartfelt, rather than things that are fleeting or untrue to the self. Second, people prefer happiness through doing something valuable toward and/or with other people, friends, family, and other intimates. Third, people like to pursue happiness in a way that is unlimited, active, developmental, and insatiable rather than limited, passive, conclusive, and satiable. Fourth, real happiness for human beings may be discovered and attained within a world of “taking action” with “less ownership”.

In future studies, it will be valuable to investigate possible reasons why men, as compared with women, and why younger people as compared with older people, attach more importance to the feeling of happiness from ownership than from taking action, while all four (men, women, younger people, and older people) value taking action more than ownership. Since education level affects this preference similarly in Japan and the US, it remains to be determined if and how more extensive learning and/or greater opportunities for education will affect the belief that taking action is more important for happiness than ownership.

It is suggested that the preference for ownership or taking action to obtain feelings of happiness in the US and other countries, such as those in Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America, should be investigated in the future. It is also important to conduct further investigations of the correlations with these preference and gender, age, level of education, and annual income in the US and other countries.

It is also suggested that a more detailed investigation on the question of material ownership should be undertaken, since very few practical psychological studies on the question of material ownership have been conducted. Further research is necessary to more fully address the question of self-ownership and no ownership, both psy- chologically and philosophically. This topic is a very important question that remains to be answered.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Y. Uchida of Kyoto University, and Professor K. Adachi of Osaka University, the editor of this journal, and several anonymous reviewers for valuable discussion.

References

- Belk, R. W. (1985). Materialism: Trait Aspects of Living in the Material World. Journal of Consumer Research, 14, 113-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/208515

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the Extended Self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 139-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209154

- Brian, M. (2010). The Appeal of Self-Ownership. Social Theory and Practice, 36, 213-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.5840/soctheorpract201036212

- Canevell, A., & Crocker, J. (2010). Creating Good Relationships: Responsiveness, Relationship Quality, and Interpersonal Goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 78-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018186

- Carter, T. J., & Gilovich, T. (2010). The Relative Relativity of Material and Experiential Purchases. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 146-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0017145

- Carter, T. J., & Gilovich, T. (2012). I Am What I Do, Not What I Have: The Differential Centrality of Experiential and Material Purchases to the Self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 1304-1317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0027407

- Curchin, K. (2007). Debate: Evading the Paradox of Universal Self-Ownership. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 15, 484-494. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2007.00288.x

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

- del Mar Salinas-Jiménez, Mª, Artés, J., & Salinas-Jiménez, J. (2011). Education as a Positional Good: A Life Satisfaction Approach. Social Indicators Research, 103, 409-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9709-1

- Delhey, J. (2010). From Materialist to Post-Materialist Happiness? National Affluence and Determinants of Life Satisfaction in Cross-National Perspective. Social Indicators Research, 97, 65-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9558-y

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very Happy People. Psychological Science, 13, 81-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415

- Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending Money on Others Promotes Happiness. Science, 319, 1687- 1688. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1150952

- Frank, R. H. (1999). Luxury Fever: Why Money Fails to Satisfy in an Era of Excess. New York: Free Press.

- Fromm, E. (1976). To Have or to Be? New York: Harper & Row.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Howell, R. T., & Hill, G. (2009). The Mediators of Experiential Purchases: Determining the Impact of Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Social Comparison. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 511-522. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760903270993

- Howell, R. T., Pchelin, P., & Iyer, R. (2012). The Preference for Experiences over Possessions: Measurement and Construct Validation of the Experiential Buying Tendency Scale. Journal of Positive Psychology, 7, 57-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.626791

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hudders, L., & Pandelaere, M. (2012). The Silver Lining of Materialism: The Impact of Luxury Consumption on Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 411-437. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9271-9

- Kasser, T. (2002). The High Price of Materialism. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. (1993). A Dark Side of the American Dream: Correlates of Financial Success as a Central Life Aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 410-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. (1996). Further Examining the American Dream: Differential Correlates of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280-287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167296223006

- Larson, R., Mannell, R., & Zuzanek, J. (1986). Daily Well Being of Older Adults with Friends and Family. Psychology and Aging, 1, 117-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.1.2.117

- Locke, J. (1988). Locke: Two Treatises of Government. P. Laslett (Ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1689). http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511810268

- Murray, S. L., Leder, S., MacGregor, J. C. D., Holmes, J. G., Pinkus, R. T., & Harris, B. (2009). Becoming Irreplaceable: How Comparisons to the Partner’s Alternatives Differentially Affect Low and High Self-Esteem People. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 1180-1191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.07.001

- Nickerson, C., Schwarz, N., & Diener, Ed., the Gallup Organization (2007). Financial Aspirations, Financial Success, and Overall Life Satisfaction: Who? and How? Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 467-515. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9026-1

- Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, State and Utopia (pp. 42-45). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Pendlebury, M., Hudson, P., & Moellendorf, D. (2001). Capitalist Exploitation, Self-Ownership, and Equality. The Philosophical Forum, 32, 207-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0031-806X.00062

- Raibley, J. R. (2012). Happiness Is Not Well-Being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 1105-1129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9309-z

- Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A Consumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 303-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/209304

- Rosenzweig, E., & Gilovich, T. (2012). Buyer’s Remorse or Missed Opportunity? Differential Regrets for Material and Experiential Purchases. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 215-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024999

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Scitovsky, T. (1976). The Joyless Economy: The Psychology of Human Satisfaction. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Taylor, R. (2005). Self-Ownership and the Limits of Libertarianism. Social Theory and Practice, 31, 465-482. http://dx.doi.org/10.5840/soctheorpract200531423

- Uchida, Y., Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., Reyes, J. A. S., & Morling, B. (2008). Is Perceived Emotional Support Beneficial? Well-Being and Health in Independent and Interdependent Cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 741- 754. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167208315157

- Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Kitayama, S. (2004). Cultural Constructions of Happiness: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5, 223-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8785-9

- Uchida, Y., Townsend, S. S. M., Markus, H. R., & Bergsieker, H. B. (2009). Emotions as within or between People? Cultural Variation in Lay Theories of Emotion Expression and Inference. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1427- 1439. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167209347322

- Uyl, D. J. D., & Rasmussen, D. B. (2003). Self-Ownership. The Good Society, 12, 50-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/gso.2004.0019

- Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To Do or to Have? That Is the Question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 1193-1202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1193

- Van Boven, L., Campbell, M. C., & Gilovich, T. (2010). Stigmatizing Materialism: On Stereotypes and Impressions of Materialistic and Experiential Pursuits. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 551-563. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167210362790

- Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2012). Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Welsch, H., & Kühling, J. (2011). Are Pro-Environmental Consumption Choices Utility-Maximizing? Evidence from Subjective Well-Being Data. Ecological Economics, 72, 75-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.04.015

- Whitchurch, E. R., Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2011). “He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not ...”: Uncertainty Can Increase Romantic Attraction. Psychological Science, 22, 172-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797610393745

- Witter, R. A., Okun, M. A., Stock, W. A., & Haring, M. J. (1984). Education and Subjective Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 6, 165-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/01623737006002165

- Xiao, J. J., & Li, H. F. (2011). Sustainable Consumption and Life Satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 104, 323-329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9746-9

- Ypi, L. (2011). Self-Ownership and the State: A Democratic Critique. Ratio, 24, 91-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9329.2010.00485.x