International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol.4 No.3(2013), Article ID:29193,5 pages DOI:10.4236/ijcm.2013.43031

Impact of Chronic Pelvic Pain on Female Sexual Function

![]()

1Department of Neurosciences and Behavioral Sciences, School of Medicine, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; 2Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, School of Medicine, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; 3Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil; 4Department of Surgery and Anatomy, University Hospital, Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil.

Email: adrianapeterson@uol.com.br, apeterson@hcrp.fmrp.usp

Received December 20th, 2012; revised January 23rd, 2013; accepted March 16th, 2013

Keywords: Chronic Pelvic Pain; Sexual Function; Depression; Women

ABSTRACT

The objective of the present study was to determine the prevalence of sexual dysfunction and depression in women with chronic pelvic pain (CPP). A case-control study was conducted on 66 women, 36 of them with CPP and 30 without this diagnosis. Depression was evaluated using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and sexual dysfunction was evaluated using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Data were analyzed statistically by the Mann-Whitney test, Fisher exact test, chi-square test, and Spearman correlation test. Regarding sociodemographic data, no significant differences were detected between populations with respect to the variables studied (age, schooling, number of children, income, salary, and marital status), indicating group homogeneity and thus increasing the reliability of the data. A cut-off of 26.55 points was used to calculate the total score for sexual function. In the group of women with CPP, 94.4% were at high risk for sexual dysfunction. Comparison of FSFI scores showed that the domains of sexual function, such as orgasm, lubrication and pain differed significantly between women with and without CPPP. Correlations were detected between the following items: orgasm × age (r = −0.01904), orgasm × number of children (r = −0. 00947), orgasm × body mass index (BMI) (r = −0.00 955), relationship × age (r = 0.03952), income × relationship (r = −0.014680), relationship × number of children (r = −0.03623), depression × relationship (r = −0.16091), desire × age (r = −0.45255), desire × number of children (r = −0.01824), lubrication × excitement (r = 0.04198), and lubrication × BMI (r = −0.01608). The prevalence of depression detected in the present study was 38.9% among women with pain and 3.3% among control women. It was observed that women with CPP suffer a negative interference regarding sexual function compared to controls. Thus, it can be seen that a specific approach related to sexuality is extremely important within the context of women with CPP. Depression was clearly associated with CPP and therefore an interdisciplinary approach is fundamental in order to solve this problem.

1. Introduction

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) has been defined as pain not exclusively of menstrual origin lasting at least six months and possibly interfering with habitual activities, requiring clinical and/or surgical intervention [1]. Its etiology is not clear and usually results from a complex interaction between the gastrointestinal, urinary, gynecological, musculoskeletal, neurological, psychological and endocrinologic systems, being also influenced by sociocultural factors [2]. CPP is a common and complex syndromic disease often of unidentified causes, rendering the diagnosis and treatment more difficult. The importance of this topic is reflected on the impact the disease has on the well-being of affected patients, interfering with their marital, social, professional and sexual life.

There is a strong association between depression and CPP [3-5]. In general, individuals with chronic pain have a long history of pain, marked psychic suffering, work and physical impairment, and distrust of treatment. These conditions may favor lack of adherence to treatment, prolong pain and suffering, impair physical and psychic functionality, and cause deterioration of quality of life [5,6].

The psychological factor may be present alone or in concomitance with others in up to 60% of cases [5]. According to the cited study, among the psychiatric disorders related to CPP the most common is depression, 25% to 50%, and anxiety, 10% to 20%. However, in a significant number of cases, a single and clear etiology of pain is not identified by means of medical exams [7].

There is an important relationship between depression and sexual function, mainly when the latter is reduced [8]. The medications used for the treatment of depression also have a negative influence on the sexual functioning of women [9]. However, Michelson et al. (Michelson, 2001) [10] evaluated the effects of fluoxetine for the treatment of depression and detected improved sexual function in most patients.

Studies (Romao, Gorayeb et al., 2011) [6] have demonstrated that CPP may involve multiple aspects of a physiological, psychic or social nature, continuing to be a challenging disease. Several authors have suggested that CPP is directly related to depression and sexual function. However, few studies have evaluated the association between pain, sexual function and depression. Thus, the objective of the present study was to assess the prevalence of sexual dysfunction and its subtypes in women seen at the Chronic Pelvic Pain Outpatient Clinic of a public university hospital in Brazil.

2. Patients and Methods

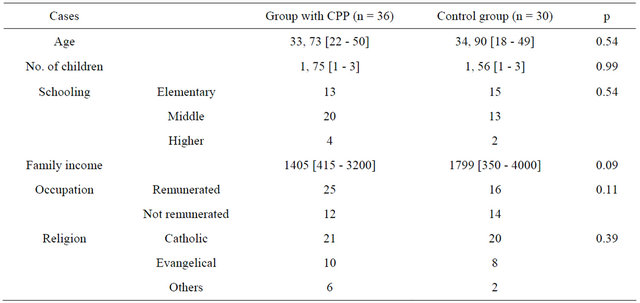

A case-control study was conducted on 66 female patients aged 18 to 45 years, 36 of whom had a diagnosis of CPP and were being treated in the Chronic Pelvic Pain Outpatient Clinic of a public university hospital, and on 30 women without CPP in the same age range and with the same sociodemographic conditions (Table 1). The following exclusion criteria were used for both groups: a history of psychiatric disorder (psychosis) preceding the disease, presence of other chronic diseases such as systemic arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cancer, presence of pregnancy, illiteracy or precarious education, i.e., patients who would be unable to understand the scales used for evaluation, and deficient patients. All patients responded to the inventories without the help of the investigator. The following instruments were used for evaluation: semi-structured interview, Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) [11,12]; Beck Depression Inventory [13-15]. Data were analyzed statistically using the GraphPad Prism 4.0* software. The instruments were analyzed according to the criteria established by the authors of the versions translated into Portuguese [12,16, 17]. The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee and all patients gave written informed consent to participate. The patients who required psychological treatment were referred to the Service of Medical Psychology of the institution.

3. Results and Discussion

No significant differences were observed between groups regarding the variables analyzed (age, schooling, number of children, monthly income, remuneration, and marital status), reflecting group homogeneity and thus increasing the reliability of the data.

Regarding the calculation of the total score for sexual function based on the cut-off of 26.55 points [18], 84.4% of the women in the CPP group showed a high risk of sexual dysfunction (Table 2). Comparison of the FSFI score showed that sexual function in the lubrication, orgasm and pain domains was significantly lower in women without CPP, as shown in Table 2, it differs from other studies that put prejudice of sexual response. Regarding the general aspects of sexual dysfunction, many studies have demonstrated a prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women (Verit, 2006) [19] reported higher rates of sexual dysfunction in women with CPP than in women without the condition (67.8% × 32.2%). (Cayan, 2004) [20] reported a 46.9% prevalence of sexual dysfunction determined by the FSFI in Turkish women aged

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the chronic pelvic pain (CPP) and control groups.

Age: median [range]; Schooling: Elementary: one to eight years of study; Middle: 9 to 14 years of study; Higher: more than 15 years of study; Family income (MW): minimum wages in Reais. p < 0.05.

Table 2. Differences in FSFI scores (median) between the group with chronic pelvic pain (CPP) and the control group regarding the specific domains.

*p < 0.05 (Fisher test). Data are reported as median. The instrument used for evaluation was the FSFI adapted to the Portuguese language (Pacagnella et al., 2008).

18 to 66 years, as opposed to a 69.6% prevalence among women with CPP. Several studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of sexual difficulties among patients with CPP [21,22]).

According to Verit et al. (2006) [19], patients with CPP express sex fantasies frequently associated with fear of experiencing pain during the intimate episode, resulting in sexual anxiety. These authors concluded that motivational, affective, cognitive and unconscious aspects may influence sexual desire. In the cited study, women with CPP reported worse sexual function regarding desire, excitement, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. Ambler et al. (Ambler, 2001) [23] demonstrated that a great majority of women with CPP had a combination of difficulties regarding excitement and performance and had problems in finding a comfortable position, fear of worsening of the pain, relationship problems and loss of self-confidence.

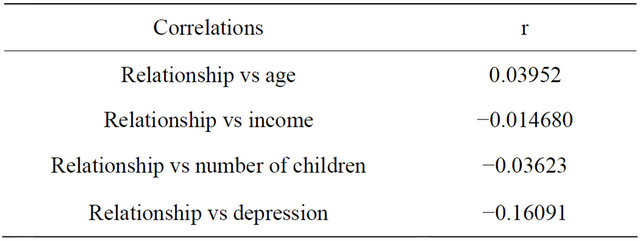

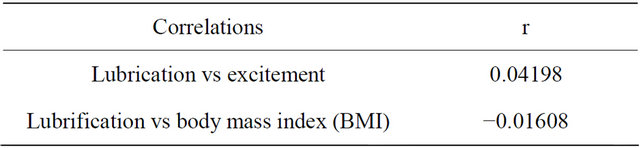

In the present study, analysis of inter-domain correlation, which provides additional information about the association between domains, revealed statistically significant results according to Tables 3-6.

In the present study there was a negative correlation between desire and age, in agreement with other studies that have demonstrated a close relationship between sexual function and age in the general population: the older the age, the greater the risk to develop sexual dysfunction [24-26].

Another factor associated with the presence of sexual dysfunction is a low educational level, as also reported by others [20,23,27]. Women with a higher educational level have a lower chance of presenting sexual dysfunction than women with a low educational level [20,28].

Blumel et al. [29] used the same instrument to assess sexual function in Chilean women aged 18 to 59 years and detected a 40% prevalence among women with sexual dysfunction, with an increase in prevalence with age.

Table 3. Significant correlations for orgasm in women with chronic pelvic pain.

Table 4. Significant correlations for relationship in women with chronic pelvic pain.

Table 5. Significant correlations for desire in women with chronic pelvic pain.

Table 6. Significant correlations for lubrification in women with chronic pelvic pain.

In the United States, Laumann and Rosen (1999) [27] reported that about 43% of women aged 18 to 59 years had some type of sexual dysfunction, and Lewis et al. (2004) published a review study which showed a prevalence of 40% to 45% in this age range. In a Brazilian study, Abdo et al. [30] reported that 28.5% of the women interviewed mentioned some sexual difficulty, although 50.9% would be considered to have sexual difficulties if specific problems such as difficulty in desire, orgasm, excitement, were summed.

The prevalence of depression detected in the present study was 38.9% among women with pain and 3.3% among control women (Table 4). Previous studies have demonstrated a significant association between CPP and depression regardless of the gynecological disease involved [22,31-33]. The prevalence of depression among women with CPP ranges from 38% to 87% [5,34,35] and from 12% to 17.2% (DSM-IV-TR 2002) [36]. Regarding depression, the present results agree with those reported by others, showing that patients with CPP have higher depression scores compared to controls.

A negative interference of the disease with sexual function was detected in women with CPP compared to control. Women with CPP have pain during sexual relations, a reduced lubrication, and anorgasmia. Thus, it was concluded that a specific approach linked to sexuality is of extreme importance for women with CPP. Also, depression is clearly associated with CPP, so that interdisciplinary care is of fundamental importance for the resolution of these problems

REFERENCES

- A. Milburn, R. C. Reiter and A. T. Rhomberg, “Multidisciplinary Approach to Chronic Pelvic Pain,” Obstetrics & Gynecology Clinics of North America, Vol. 20, No. 4, 1993, pp. 643-661.

- F. M. Howard, “The Role of Laparoscopy in the Evaluation of Chronic Pelvic Pain: Pitfalls with a Negative Laparoscopy,” Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1996, pp. 85-94. doi:10.1016/S1074-3804(96)80116-2

- G. P. Kurita, “Adesão ao Tratamento da dor Crônica: Estudo de Variáveis Demográficas, Terapêuticas e Psicossociais,” Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, Vol. 61, No. 2B, 2003, pp. 416-425. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2003000300017

- C. P. Lorençatto and M. J. Navarro, “Depression in Women with Endometriosis with and without Chronic Pelvic Pain,” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, Vol. 85, No. 1, 2006, pp. 88-92. doi:10.1080/00016340500456118

- A. P. Romao, R. Gorayeb, et al., “High Levels of Anxiety and Depression Have a Negative Effect on Quality of Life of Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain,” International Journal of Clinical Practice, Vol. 63, No. 5, 2009, pp. 707- 711. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02034.x

- A. P. Romao, R. Gorayeb, et al., “Chronic Pelvic Pain: Multifactorial Influences,” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, Vol. 17, No. 6, 2011, pp. 1137-1139. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01485.x

- T. A. Gelbaya and H. E. El-Halwagy, “Focus on Primary Care: Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women,” Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, Vol. 56, No. 12, 2001, pp. 757- 764. doi:10.1097/00006254-200112000-00002

- R. Basson, “Human Sex-Response Cycles,” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2001, pp. 33-43. doi:10.1080/00926230152035831

- J. M. Ferguson, “The Effects of Antidepressants on Sexual Functioning in Depressed Patients: A Review,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 62, Suppl. 3, 2001, pp. 22-34.

- D. Michelson, M. Schmidt, J. Lee and R. Tepner, “Changes in Sexual Function during Acute and SixMonth Fluoxetine Therapy: A Prospective Assessment,” urnal of Sex & Marital Therapy, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2001, pp. 289-302. doi:10.1080/009262301750257146

- R. Rosen, C. Brown, J. Heiman, S. Leiblum, C. M. Meston, R. Shabsigh, D. Ferguson and R. D’Agostinho, “The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A Multidimensional Self-Report Instrument for the Assessment of Female Sexual Function,” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2000, pp. 191-208. doi:10.1080/009262300278597

- R. V. Pacagnella, O. M. Rodrigues Jr. and C. Souza, “Adaptação Transcultural do Female Sexual Index,” Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2008, pp. 416- 426. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2008000200021

- G. V. Hamilton and K. Macgrowan, “What Is Wrong with Marriage?” 1929.

- A. W. Beck, M. Mendelson, J. Mock and G. Erbaugh, “An Inventory for Measuring Depression,” Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol. 4, No. 6, 1961, pp. 53-63. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

- A. T. Beck, R. A. Steer and M. G. Garbin, “Psychometric Properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: TwentyFive Years of Evaluation,” Clinical Psychology Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1988, pp. 77-100. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5

- C. A. M Pimenta, D. A. L. M. Cruz and J. L. F. Santos, “Instrumentos Para Avaliação de Dor: O Que há de novo em Nosso Meio,” Arq Brasil Neurocirurg, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1988, pp. 15-24.

- M. P. A. Fleck, S. Louzada, M. Xavier, E. Chachamovich, G. Vieira, L. Santos and V. Pinzon, “Apliocação da Versão em Português do Instrumento Abreviado de Avaliação de Qualidade de vida Whoqol-Bref,” Revista de Saúde Pública, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2000, pp. 178-183. doi:10.1590/S0034-89102000000200012

- M. Wiegel, C. Meston and R. Rosen, “The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): Cross-Validation and Development of Clinical Cutoff Scores,” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2005, pp. 1-20. doi:10.1080/00926230590475206

- F. F. Verit, A. Verit and E. Yeni, “The Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction and Associated Risk Factors in Womem with Chronic Pelvic Pain: Cross-Sectional Study,” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 274, No. 5, 2006, pp. 297-302. doi:10.1007/s00404-006-0178-3

- S. Cayan, E. Akbay, M. Bozly, B. Canpolat and D. Acar, “The Prevalence of Female Sexual Dysfunction and Potential Risk Factors That May Impair Sexual Function in Turkish Women,” Urologia Internationalis, Vol. 72, 2004, pp. 52-57. doi:10.1159/000075273

- T. Maruta, D. Osborne, D. W. Swanson and J. M. Halling, “Chronic Pain Patients and Spouses: Marital and Sexual Adjustment,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Vol. 56, No. 5, 1981, pp. 307-310.

- T. N. Monga, G. Tan, H. J. Ostermann, U. Monga and M. Grabois, “Sexuality and Sexual Adjustment of Patients with Chronic Pain,” Disability and Rehabilitation, Vol. 20, No. 9, 1998, pp. 317-329. doi:10.3109/09638289809166089

- N. Ambler, A. C. Williams, P. Hill, R. Gunary and G. Cratchley, “Sexual Difficulties of Chronic Pain Patients,” Clinical Journal of Pain, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2001, pp. 138- 145. doi:10.1097/00002508-200106000-00006

- S. Kingsberg, “The Impact of Aging on Sexual Function in Women and Their Partners,” Archives of Sexual Behavior, Vol. 31, No. 5, 2002, pp. 431-437. doi:10.1023/A:1019844209233

- R. Hayes and L. Dennerstein, “The Impact of Aging on Sexual Function and Sexual Dysfunction in Women: A Review of Population-Based Studies,” Journal of Sexual Medicine, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2005, pp. 317-330. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20356.x

- N. D. Vogeltanz, S. C. Wilsnack, et al., “Sociodemographic Characteristics and Drinking Status as Predictors of Older Women’s Health,” Journal of General Psychology, Vol. 126, No. 2, 1999, pp. 135-147. doi:10.1080/00221309909595357

- E. O. Laumann, A. Paik and R. C. Rosen, “Sexual Dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and Predictors,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 281, No. 6, 1999, pp. 537-544.

- R. Shabsigh, “Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction,” In: P. C. Walsh, A. B. Retik, E. D. Vaughan and A. J. Wein, Eds., Campbell’s Urology, 8th Edition, W. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2002.

- J. B. Blumel, P. Cataldo, A. Carrasco, H. Izaguirre and S. Sarrá, “Índice de Function Sexual Femenina: Un Test Para Evaluar la Sexualidad de la Mujer,” Revista Chilena de Obstetricia y Ginecología, Vol. 69, No. 2, 2004, pp. 118-125. doi:10.4067/S0717-75262004000200006

- C. H. N. Abdo, W. M. Oliveira Jr., E. D. Moreira Jr. and J. A. S. Fittipaldi, “Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction and Correlated Conditions in a Sample of Brazilian Women: Results of the Brazilian Study on Sexual Behavior (BSSB),” International Journal of Impotence Research, Vol. 16, 2004, pp. 160-166. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3901198

- R. Renaer, H. Vertommen, P. Nijs, et al., “Psychological Aspects of Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 134, No. 1, 1979, pp. 75-80.

- H. Gomibuchi, M. Doi, et al., “Is Personality Involved in the Expression of Dysmenorrhea in Patients with Endometriosis?” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 169, No. 3, 1993, pp. 723-725.

- G. Tan, U. Monga, J. Thornby and T. Monga, “Sexual Functioning, Age, and Depression Revisited,” Sexuality and Disability, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1998, pp. 77-86. doi:10.1023/A:1023023924804

- M. J. Bair, W. Katon and K. Kroenke, “Depression and Pain Comorbidity: A Literature Review,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 163, No. 20, 2003, pp. 2433-2445. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433

- M. M. C. Castro, L. Quarantini, S. Batista-Neves, et al., “Validade da Escala Hospitalar de Ansiedade e Depressão em Pacientes com dor Crônica,” Revista Brasileira de Anestesiologia, Vol. 56, No. 5, 2006, pp. 470-477. doi:10.1590/S0034-70942006000500005

- DSM-IV-TR, “Manual Diagnóstico e Estatístico de Transtornos Mentais,” Porto Alegre, 2002.