Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.2(2013), Article ID:32473,7 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.32029

Latina mothers feeding their children: A focus group pilot study

![]()

1Department of Sociology, University of California, Irvine, USA

2Department of Social Ecology, University of California, Irvine, USA

3Program in Nursing Science, University of California, Irvine, USA

4Newport Mesa Unified School District, Costa Mesa, USA

Email: banyja@gmail.com

Copyright © 2013 James A. Bany et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 30 March 2013; revised 30 April 2013; accepted 15 May 2013

Keywords: Obesity; Preschool Children; Latino Health; Nutrition

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to better understand current knowledge of health and nutrition, barriers to improving eating habits, and preferences for schoolbased interventions among low-income Latina mothers. Qualitative research methods and analysis were employed. Eighteen mothers of preschool-aged children participated in a focus group interview. Findings indicate that mothers have an understanding of healthy eating, but identified issues with connecting food with weight and in understanding definitions of “obese”. Further, respondents identified barriers to incorporating healthier foods and cooking methods into daily life, due to family food preferences, cultural practices, and schedules. Mother’s concerns about the future weight and the health of their children appeared to motivate interest in improving feeding behaviors. Desired interventions of mothers highlight the importance of culturally relative solutions to behavior change towards healthy eating.

1. INTRODUCTION

“I have noticed that many kids, even before they get to preschool age, they seem to already be overweight. As mothers, we do not have the information to help our children from birth because if we helped them earlier we may avoid them getting to a point where now they are eating out of control and already overweight and it is harder for them to change that once it has already started. We need, I think, to get information to parents a lot sooner. And not wait until kids are 12 or 16 years old to tell us that our children are overweight.”

Focus group participant Obesity rates in the US among preschool-aged Latino children hovers around 22%, which remains the second highest prevalence of obesity among all children in this age group [1,2]. As Latino children grow toward adolescence, so does the proportion of obesity: thirty-three percent of Latino children in the US are considered overweight or obese [3] while 44% of Mexican-American adolescents aged 12 - 19 are overweight or obese [4]. With the rise in obesity comes a rise in chronic illness. Particularly concerning is the increase of children presenting with illnesses thought to occur predominantly in the adult population, such as high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, and Type 2 diabetes [5,6]. Although studies have attempted to understand effective interventions that promote healthier eating habits, the adoption of dietary and fitness lifestyle changes known to reduce obesity and chronic disease risks has not occurred in any meaningful proportion [7]. Presented here are preliminary data on the question of whether parents perceive the problem of childhood obesity, and what struggles parents face in helping their children to be healthy. The aim of this study was to better understand current health and nutrition knowledge, barriers to improving eating habits, and preferences for school-based interventions among low-income Latina mothers through the use of focus group interviews.

2. BACKGROUND

While obesity rates in the US continue to rise, the adoption of dietary and fitness lifestyle changes known reduce chronic disease risks has not occurred in any meaningful proportion [7]. Many parents are aware of the issue of obesity, but often struggle to feed their children what they view as a healthy diet, and/or facilitate physical activity. In fact, parents reveal a strong interest in improving the diets they feed their children and themselves, in understanding what constitutes a healthy weight for children, and a concern for the physical and psychological ramifications of carrying excess weight [7-9]. Many studies show that Latino parents actually possess a fair amount of knowledge about good nutrition and exercise, and possess a strong perception of self-efficacy in their ability to control their child’s weight [5,10,11]. Snethen and colleagues [5] found that time, money, transportation, and the lack of a safe community environment were the primary factors that prevented parents from preparing healthier meals, and from knowingly using food as a reward or to placate distress. Even the children interviewed recognized the problem of time, and of using food as a reward. Further, Latino parents are knowledgeable of the risks of using unhealthy feeding strategies and aware of their own habits as providing a model for their children [12]. The problem, it seems, lies in the application of generalized knowledge to one’s own child [10].

Identifying specific needs that could help parents better implement improved nutrition and exercise for their children has been the subject of several studies. Some needs identified include brief written materials (not videos) of “how to” information that is age appropriate for feeding, and that provides health-related knowledge [13]. How to prepare traditional foods in a healthy way was another need identified by Latina mothers [5]. Studies have endeavored to elucidate effective interventions that promote healthier eating habits, yet the adoption of positive behavior changes toward addressing obesity remains challenging. As monies are increasingly available to support child obesity interventions, it is important to discover the key ingredients necessary to effect change, and those factors that pose barriers to implementing effective strategies. This paper presents parents’ existing knowledge of health, obesity, and eating practices, and parental preferences for intervention programs, as explored through focus groups. The findings will be used to develop culturally specific interventions for this population.

3. METHODS

This research was a collaborative effort between the University of California, Irvine and an Orange County school district serving a primarily low-income, Latino population. The data in this paper present the qualitative aspect of a larger study looking at obesity among Latino preschool children. Participants were included in the study if they were Latino, and had at least one child attending preschool in the district. Although three fathers participated in the larger study, only mothers volunteered to participate in the focus group. Prior to the focus groups, mothers and children had their height and weight measured for BMI calculation and also completed a brief questionnaire to gather demographic information. A bilingual, bicultural Latina nurse-practitioner student facilitated two focus groups of participants. Both focus groups were conducted entirely in Spanish, lasted approximately 60 minutes each, and were audio recorded. A bilingual staff member transcribed each tape verbatim and then translated the text from Spanish to English.

Transcripts were analyzed and coded utilizing an inductive methodology [14]. Emergent and frequent themes related to mothers’ knowledge, barriers to change, and educational preferences. An iterative process developed thematic subcategories. Initial coding and subcategory identification was completed separately by investigators, followed by meetings where discussion of analytical procedures, evaluation of findings, and reaching a final consensus occurred.

4. RESULTS

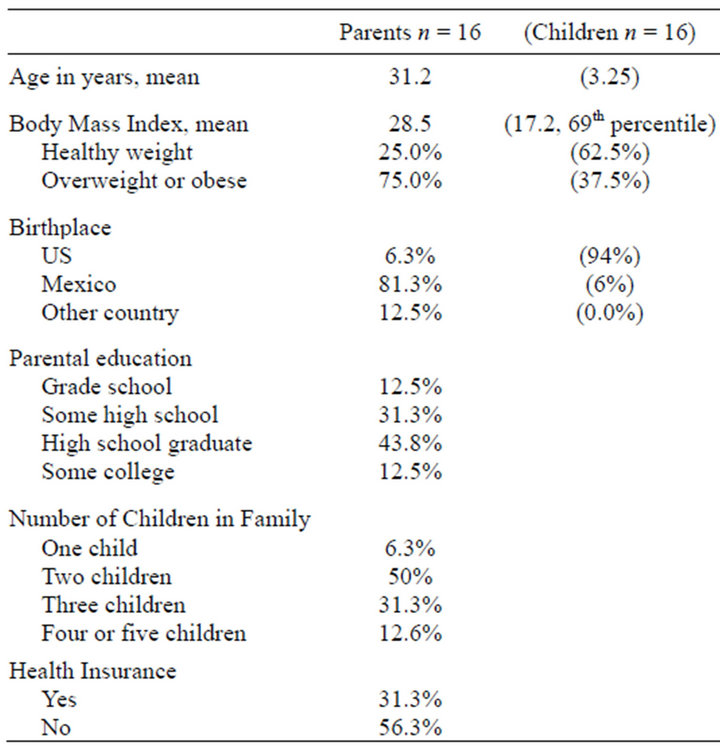

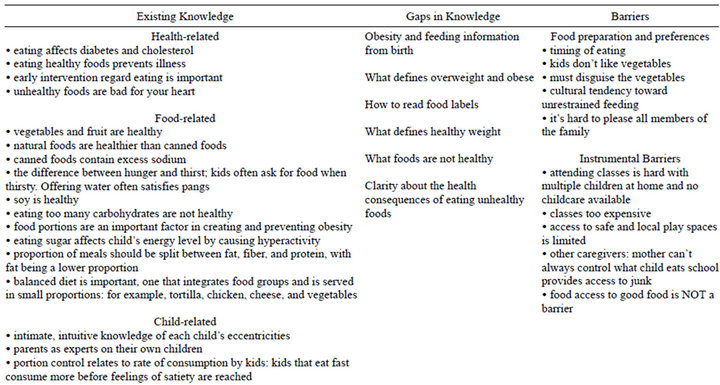

Of the 18 participants, two were missing BMI and survey data. Of the remaining 16, seventy-five percent of mothers were overweight or obese, with an average BMI of 28.5 (overweight). Thirty-eight percent of children were overweight or obese, with an average BMI in the 69th percentile (overweight = 80th percentile). Forty-four percent of mothers were high school graduates, with 13% having attended some college. Eighty-one percent of parents were born in Mexico, and 56% had no health insurance (see Table 1). Content regarding knowledge, barriers to ideal feeding, and educational preferences is summarized in Table 2.

Respondents demonstrated a general understanding that food affects one’s health, and that eating healthy foods can help prevent illness. One respondent explained: “food is definitely related to being healthy—doesn’t the saying go—you are what you eat? If we eat a lot of fatty foods, our hearts is what suffers the most. We must try to eat as healthy as possible in order to be role models for our children to eating healthy, such as fruits and vegetables”. Respondents identified fruits and vegetables, fresh foods rather than canned, and soy as healthy foods.

Food components also came up in the discussion, where carbohydrates and fats were identified as unhealthy, fiber and protein as healthier components, and that the balance and proportions between components is important. Sodium contained in canned foods, and convenience foods, such as cookies and cakes, were also mentioned as un-

Table 1. Demographics.

healthy. Respondents also demonstrated knowledge about the importance of portion size to their children’s health. However, while respondents possessed existing knowledge of healthy eating, they were less certain about how it related to weight.

Mothers’ expressed confusion and ambiguity in the messages they received about healthy weight, complicating the implementation of healthy feeding practices. One mother explains her frustration with information received from her child’s doctor: “...we take them to the doctor and all they say is, ‘they’re fine,’ but what is fine?” Mothers reported confusion in understanding definitions of “obese,” and how information received from schools and health professionals pertained to their child and family in particular. Commenting on the lack of clarity in the information she received from her child’s doctor, one mother explained: “... they do tell us, but I still don’t know what it means.” As a result of this ambiguity in information received, many mothers perceived their children’s weight inaccurately, mostly through underestimation. Even so, many mothers reported concern regarding their child becoming overweight in the future if they did not adhere to healthy feeding practices. However, mothers reported a lack in their knowledge of how to feed their children in a way that prevents obesity. Illustrating the common frustration between messages of healthy eating and weight and implementation in feeding practices, one mother states: “Many times it seems that we may be feeding our babies because they are crying and maybe they are not even hungry. If we learn to know what to do and how to do it, we may avoid having overweight children.”

During the focus groups respondents identified numerous barriers to providing healthy foods to their children, including time management, access to affordable and healthy food, family schedules, and challenges getting their children to eat food they prepared. The following respondent illustrates the struggle to implement healthy food practices into their daily lives: “I think that natural foods are the most healthy because sometimes I think that we as moms are so busy running around because of work and it’s easy for us to grab a canned food, like beans, and I think that is not very nutritious, even though it says it is.” Respondents also expressed frustration with changing food preferences of their children to incorporate healthy foods. A primary complaint was that kids simply do not like vegetables. Mothers felt they must hide or disguise vegetables for them to be eaten. One respondent explained: “Sometimes I make meatballs, so the vegetables are hidden in them. I have to hide them or else they won’t eat them!” Respondents generally agreed that it is a battle to get kids to eat the foods they prepare. They stated a lack of repertoire and/or skills to cook food that was both healthy and that their families would eat.

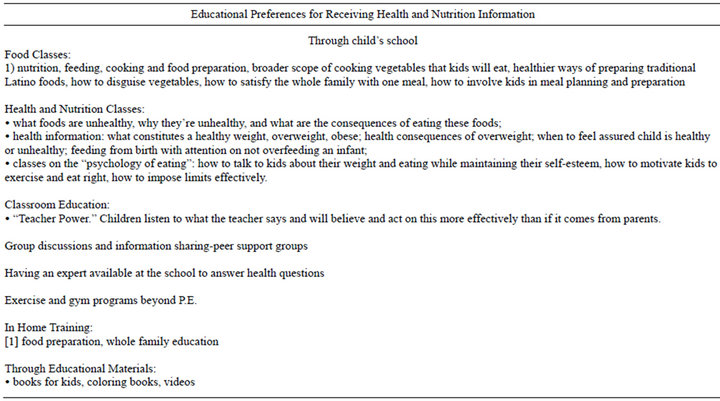

Working against ingrained habits posed further difficulties for mothers, though they might learn tools for healthy cooking from school programs or health professsionals, continuing it at home was a great challenge. One respondent explained the challenge of implementing healthy eating habits into existing routines: “…you need to practice it every day and begin a routine. Many times we may do it for 2 or 3 days and forget about it, and go back to the old ways-need to change our habits.” Some mothers cooked multiple meals to suit all family members’ varying preferences and often felt defeated by responses to their efforts. Finally, mothers cited Latino culture as a barrier to healthy eating, including cultural dishes being unhealthy and serving larger portions. One respondent states: “As a Latin person, I have seen that if a child asks for more we give them more and more and then they start to get used to eating big portions, so portions I think is very important.” Mothers identified interventions to address their barriers including programs at school that helped mothers incorporate healthier foods, cooking methods, schedules, and varying food preferences into daily life. Mothers also thought classroom education, and dissemination of educational materials to children might be useful.

5. DISCUSSION

The results of this study expand on previous studies, by providing additional insights into food-, weight-, and lifestyle-related issues specific to a Mexican-American population. Many issues raised are of general concern as well.

Table 2. Knowledge, barriers to change, and educational preferences.

1) Mothers in our study inaccurately perceived their child’s weight status. While this is not unique among Latinos, many Latinos perceive excess weight as representing a healthy, strong, and safe child [15]. Mothers often consider heavier children safer—less fragile—than thinner children. Inaccurate weight perceptions of children by parents have been theorized to inhibit parents’ attempt to promote more healthful practices in their children [16]. However, accurate weight perceptions have not been shown to increase engagement in healthier activity and dietary behaviors, but instead, may lead to poorer health behaviors (such as controlling and restrictive feeding) that increase children’s weight in the long run [17]. Furthermore, because mothers often define the health of their children as the ability to play and engage in all aspects of life, and define obesity as declining physical abilities, focusing more on a healthy home environment that promotes healthy eating and physical activity (than focusing on weight specifically) may be a more effective approach in slowing children’s weight gain [18].

2) Children’s unwillingness to eat vegetables and other healthier foods was a key barrier mothers identified. Studies focused on understanding factors that contribute to greater fruit and vegetable (FV) consumption find that accessibility and taste preferences [19], habits [20], and cognitive development [21] are prime determinants. In terms of cognitive development, likes and dislikes of 4 to 5-year olds are based on appearance and texture, which grows toward taste attributes in 11 and 12-year olds. Other determinants of increased FV intake include age and gender (girls and younger children have higher or more frequent FV intake than boys and older children), SES, and parental intake [22]. Aldridge, Dovey and Halford [23] also discuss aspects of food familiarity in relation to enthusiasm for, or fear of, trying new foods, specifically in terms of visual, taste, contextual (how foods should be prepared), and categorical (which family certain foods belong to) familiarity. Exposing toddlers to picture books about fruit and vegetables may increase familiarity with the origins and appearance of unfamiliar foods, thereby increasing children’s willingness to accept FV’s into their diets [24].

3) Mothers stated that they had difficulty sustaining healthy behavior changes longer than a few days, mainly due to an unclear understanding of the link between healthy foods and weight, time management, and children’s preferences. Understanding how important the changes are to the health of their children may provide motivation toward more permanent lifestyle and food consumption changes. Connecting the dots between weight, food consumption patterns, and their child’s health may help to establish sustaining behavior changes. Framing messages in a way that resonate with parents and reflect their concerns may improve intervention efficacy and longevity [25].

4) An unanticipated findings was that mothers in our study discussed that the focus group itself was helpful in understanding obesity and challenges around feeding their families. Many respondents considered the focus group an intervention in and of itself. Group intervenetions can also incorporate techniques that promote sharing existing parental knowledge, which may empower whole groups in their efforts toward more healthful eating. Parent groups may provide a support system for shared understanding, problem solving, and contributing personal experiences and ideas about effective ways to talk with children about their weight, without damaging their self-esteem [26].

5) Several mothers in our study reported learning to cook from their mothers and past generations, which strengthen suggestions made for interventions that enhance traditional meals with healthier alterations. Traditional Mexican diets can be characterized as typically healthy, with regular consumption of beans, corn tortillas, salads, soups, stews, fresh chilies, tomatoes, onions, and meat. Vegetable and fruit consumption is generally high in Mexican diets [27]. Selective acculturation however, may pose as a food-related determinant of obesity in Latina women, where some traditional health behaviors are maintained while new health behaviors are acquired as they settle into American culture [28]. Thus, culturally-aware nutritionists, dietitians, or RN-led groups that facilitate peer connections and discussions about traditional and American culture in relation to nutrition, feeding, weight, and cooking may foster home environments that promote healthier eating and physical activity, thus providing more effective and sustainable interventions [29].

6) Finally, mothers in our sample highlighted the power teachers have over students’ receptivity to new information. Because children have a high degree of trust in what teachers say, mothers felt that teachers educating kids about eating vegetables might increase their feeding success at home. Teachers don’t always feel they have the knowledge, time, and resources to teach nutrition in the classroom, however [30]. “Team teaching”, where teachers implement programs in conjunction with nutritionists, dietitians, or health educators, has been offered as a possible way to reduce constraints on classroom nutritional education [31].

7) Limitations of this study include the small sample size and single focus group meetings, which may limit the generalization of our results to the larger population, or to the broader Mexican-American population. Selfselection for participation by mothers that may be more interested in or knowledgeable about the study topic, and the absence of fathers’ input, may also bias our results. Future research should involve greater numbers of participants, repeated interviews to validate conclusions, include fathers, and perhaps focus on separate origins of Latino ethnicity in order to ascertain where interventions might overlap or diverge due to cultural differences.

6. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, Latina mothers of preschool-aged children may inaccurately classify the weight categories of their children, but concern for the future weight and health of their children appears to drive interest and motivation for improved feeding behaviors. Latina mothers may have general knowledge of healthy eating, but the lack of clarity in information they receive from various sources leaves them with unclear understandings of healthy eating as it relates to their child’s weight. Further, barriers make it difficult to implement healthy eating practices. Thus, interventions that focus on creating a healthier home environment and that are culturally relative to Latinos, rather than weight-oriented interventions, are likely to be more impactful.

REFERENCES

- Sharma, A.J., Grummer-Strawn, L.M., Dalenius, K., Galuska, D., Anandappa, M., Borland, E., Mackintosh, H. and Smith, R. (2009) Obesity prevalence among low-income, preschool-aged children—United States, 1998- 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 58, 769- 773.

- Anderson, S.E. and Whitaker, R.C. (2009) Prevalence of obesity among US preschool children in different racial and ethnic groups. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163, 344-348. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.18

- Rosas, L., Guendelman, S., Harley, K., Fernald, L.H., Neufeld, L., Mejia, F. and Eskenazi, B. (2011) Factors associated with overweight and obesity among children of mexican descent: Results of a binational study. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13, 169-180. doi:10.1007/s10903-010-9332-x

- Ogden, C.L., Carroll, M.D., Kit, B.K. and Flegal, K.M. (2012) Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among us children and adolescents, 1999-2010. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 307, 483- 490. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.40

- Snethen, J.A., Hewitt, J.B. and Petering, D.H. (2007) Addressing childhood overweight: Strategies learned from one latino community. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 18, 366-372. doi:10.1177/1043659607305197

- Yin, L., Wills, H., Clarke, N., Shacks, J., Bottrell, C. and Poulsen, M.K. (2009) Cardiovascular risk in preschool children. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition, 1, 197-204.

- Kones, R. (2011) Is prevention a fantasy, or the future of medicine? A panoramic view of recent data, status, and direction in cardiovascular prevention. Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease, 5, 61-81. doi:10.1177/1753944710391350

- Hughes, C.C., Sherman, S.N. and Whitaker, R.C. (2010) How low-income mothers with overweight preschool children make sense of obesity. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 465-478. doi:10.1177/1049732310361246

- James, K.S., Connelly, C.D., Gracia, L., Mareno, N. and Baietto, J. (2010) Ways to enhance children’s activity and nutrition (WE CAN)—A pilot project with Latina mothers. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 15, 292-300. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6155.2010.00252.x

- Kersey, M., Lipton, R., Quinn, M.T. and Lantos, J.D. (2010) Overweight in Latino preschoolers: Do parental health beliefs matter? American Journal of Health Behavior, 34, 340-348. doi:10.5993/AJHB.34.3.9

- Glassman, M.E., Figueroa, M. and Irigoyen, M. (2011) Latino parents’ perceptions of their ability to prevent obesity in their children. Family & Community Health, 34, 4-16. doi:10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181fdeb7e

- Gomel, J.N. and Zamora, A. (2007) Englishand Spanishspeaking Latina mothers’ beliefs about food, health, and mothering. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 9, 359-367. doi:10.1007/s10903-007-9040-3

- McGarvey, E.L., Collie, K.R., Fraser, G., Shufflebarger, C., Lloyd, B. and Norman Oliver, M. (2006) Using focus group results to inform preschool childhood obesity prevention programming. Ethnicity & Health, 11, 265-285. doi:10.1080/13557850600565707

- Lofland, J., Snow, D.A., Anderson, L. and Lofland, A.L.H. (2005) Analyzing social settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis. Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont.

- Sosa, E.T. (2012) Mexican American mothers’ perceptions of childhood obesity: A theory-guided systematic literature review. Health Education & Behavior, 39, 396- 404. doi:10.1177/1090198111398129

- Towns, N. and D’Auria, J. (2009) Parental perceptions of their child’s overweight: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 24, 115-130. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2008.02.032

- Neumark-Sztainer, D., Wall, M., Story, M. and van den Berg, P. (2008) Accurate parental classification of overweight adolescents’ weight status: Does it matter? Pediatrics, 121, e1495-e1502.

- Guerrero, A.D., Slusser, W.M., Barreto, P.M., Rosales, N.F. and Kuo, A.A. (2011) Latina mothers’ perceptions of healthcare professional weight assessments of preschool-aged children. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15, 1308-1315. doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0683-7

- Blanchette, L. and Brug, J. (2005) Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among 6 - 12-year-old children and effective interventions to increase consumption. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 18, 431-443. doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00648.x

- Reinaerts, E., de Nooijer, J., Candel, M. and de Vries, N. (2007) Explaining school children’s fruit and vegetable consumption: The contributions of availability, accessibility, exposure, parental consumption and habit in addition to psychosocial factors. Appetite, 48, 248-258. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2006.09.007

- Zeinstra, G., Koelen, M., Kok, F. and de Graaf, C. (2007) Cognitive development and children’s perceptions of fruit and vegetables; a qualitative study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 4, 30. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-30

- Rasmussen, M., Krolner, R., Klepp, K.-I., Lytle, L., Brug, J., Bere, E. and Due, P. (2006) Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Part I: quantitative studies. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 3, 22.

- Aldridge, V., Dovey, T.M. and Halford, J.C.G. (2009) The role of familiarity in dietary development. Developmental Review, 29, 32-44. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2008.11.001

- Heath, P., Houston-Price, C. and Kennedy, O.B. (2011) Increasing food familiarity without the tears. A role for visual exposure? Appetite, 57, 832-838. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.315

- Slater, A., Bowen, J., Corsini, N., Gardner, C., Golley, R. and Noakes, M. (2010) Understanding parent concerns about childrens’ diet, activity and weight status: An important step towards effective obesity prevention interventions. Public Health Nutrition, 13, 1221-1228. doi:10.1017/S1368980009992096

- Slusser, W., Prelip, M., Kinsler, J., Erausquin, J.T., Thai, C. and Neumann, C. (2011) Challenges to parent nutrition education: a qualitative study of parents of urban children attending low-income schools. Public Health Nutrition, 14, 1833-1841. doi:10.1017/S1368980011000620

- Waldstein, A. (2010) Popular medicine and self-care in a Mexican migrant community: Toward an explanation of an epidemiological paradox. Medical Anthropology, 29, 71-107. doi:10.1080/01459740903517386

- Yeh, M.-C., Viladrich, A., Bruning, N. and Roye, C. (2009) Determinants of Latina obesity in the United States: The role of selective acculturation. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20, 105-115. doi:10.1177/1043659608325846

- Carnell, S., Edwards, C., Croker, H., Boniface, D. and Wardle, J. (2005) Parental perceptions of overweight in 3 - 5 years olds. International Journal of Obesity, 29, 353- 355.

- Henry, B.W., White, N.J., Smith, T.J. and LeDang, L.T. (2010) An exploratory look at teacher perceptions of school food environment and wellness policies. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition, 2, 304-311.

- Sharma, M. (2011) Dietary education in school-based childhood obesity prevention programs. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal, 2, 207S-216S.