Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.2 No.3(2012), Article ID:23147,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.23031

The unexpected emotional similarities and behavioral differences of Japanese men experiencing parenthood in Japan and the USA

![]()

Department of Nursing Human Health Science, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan

Email: htaniguc@hs.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp

Received 20 April 2012; revised 16 May 2012; accepted 26 May 2012

Keywords: Japanese Men; Becoming a Father; Comparative View Points; Phenomenological Approach

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to understand the impact of childbirth and the experience of fatherhood on Japanese men in Japan and a foreign country. Descriptive phenomenology was used to study a total of 14 Japanese men who attended childbirth and experienced parenting in the United States and Japan. The Colaizzi method of data analysis was used to analyze responses to open-ended questions. Responses to these questions showed several similarities between the two groups of men. First, men in both countries felt closer to with their spouses having gone through the experience of childbirth together. Second, both groups nevertheless recognized a strong bond between mother and the baby, leading them to feel at times isolated. Third, both groups were concerned about their wives’ emotional swings during pregnancy and child rearing. Finally, both groups were more focused on their wives and babies than themselves. There were also several interesting differences. Japanese men who were living in Hawaii were more involved in taking care of their children and in helping with household chores than those living in Japan. This was due to living in a more family-oriented society, as well as a result of limited support from their extended families back in Japan. A result of spending more time with their wives and babies was that Japanese men in the United States understood more fully the stress of childcare. On the other hand, due to Japan’s work-oriented society, men in Japan relied more on support from their extended families, leaving them less time with their wives and children. This study clearly shows that social support systems alter gender roles and behavior, leading to significant differences in the experience of parenthood in Japan and a foreign country.

1. INTRODUCTION

Family roles have changed across the globe in the last few decades with men taking on much more of the responsibility for child rearing, including contributing to household management. In Japan, men have traditionally been the breadwinners. This boundary became a symbol of masculinity for Japanese men with each generation being raised to maintain this order. In the cultural traditions surrounding childbirth, men were outsiders. Japanese have a distinct childbirth custom called “satogaeri bunben” that allows pregnant women to be treated with special care [1]. “Satogaeri bunben” means that pregnant women return to their family homes for the delivery and then stay with their families to get sufficient support, resting physically and psychologically for a few months after childbirth. During this period, expectant fathers or new fathers are separated from their new families for several months. Recently, women’s participation in the workforce has increased so that Japanese men have been forced to alter the traditional role of father by increasing their participation in the nuclear families [2]. Therefore, attending childbirth has recently become more popular among Japanese men [3,4]. However, the tradition of “satogaeri bunben” is still widely practiced. It is not easy for young fathers to change such customs, for they are confronted by gender roles that are deeply rooted in Japanese social structure. [5]. Conversely, in American society, fathers have become routine participants in labor, delivery, and child rearing, with birth being a time when men are most receptive to being involved in the lives of their children [6]. In addition, after childbirth, they play a crucial role in being active childcare participants [7]. When Japanese men who were born and raised in Japan become fathers in the United States, how does the responsibility of having a new family with limited support affect their gender role? How do they grow and change through the experience of parenthood and under the influence of other cultural norms? The purpose of this study was to use a comparative approach to understand the impact of fatherhood on Japanese men in Japan and a foreign country.

2. METHODS

The research design of this study was descriptive, using a phenomenological approach [8]. The goal was to obtain an understanding of the meaning of the lived experience of childbirth and parenting in a foreign country and Japan, focusing particularly on a comparative view of Japanese men in Japan and the United States. The inclusion criteria for Japanese men was that they were born and raised in Japan, that they have attended childbirth, that they be experiencing parenting for the first time, and that they have a living child around 1 year of age and a Japanese partner. This study was conducted after receiving ethical approval from IRB of the University of Hawaii at Manoa and Kyoto University.

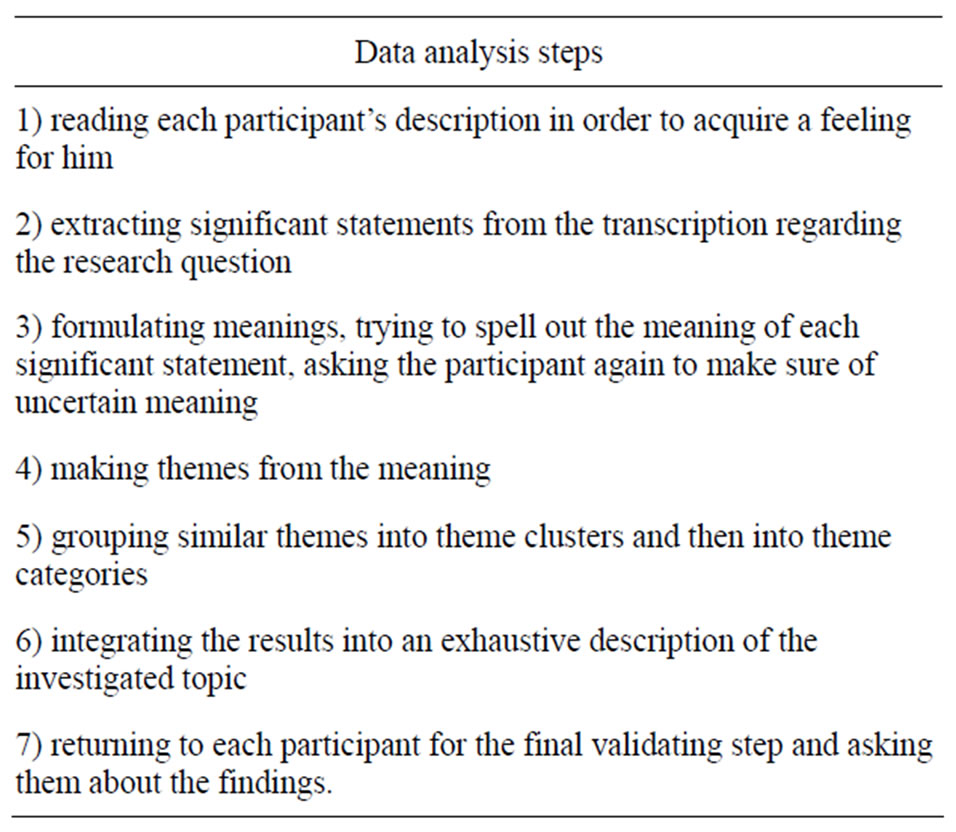

Participants were identified through word of mouth from participants of a previous study [9] and the social net work. Sample size was determined by consideration of obtaining maximum information and to reach saturation on the phenomenon under study [10]. All interviews were conducted using an open-ended, in-depth interview under IC recording. The researcher began each interview with the following question. “Tell me about your experience of becoming a father. What was the best and/or most challenging part of becoming a father?” Each interview lasted 45 minutes to an hour and took place in a location that was the most comfortable and convenient for the participants. The analysis used Colaizzi method [11] as well as the computer software NVIVO 8. All IC records of interviews were transcribed and analyzed according to the procedure for the analysis of written protocols by Colaizzi in Table 1.

3. FINDINGS

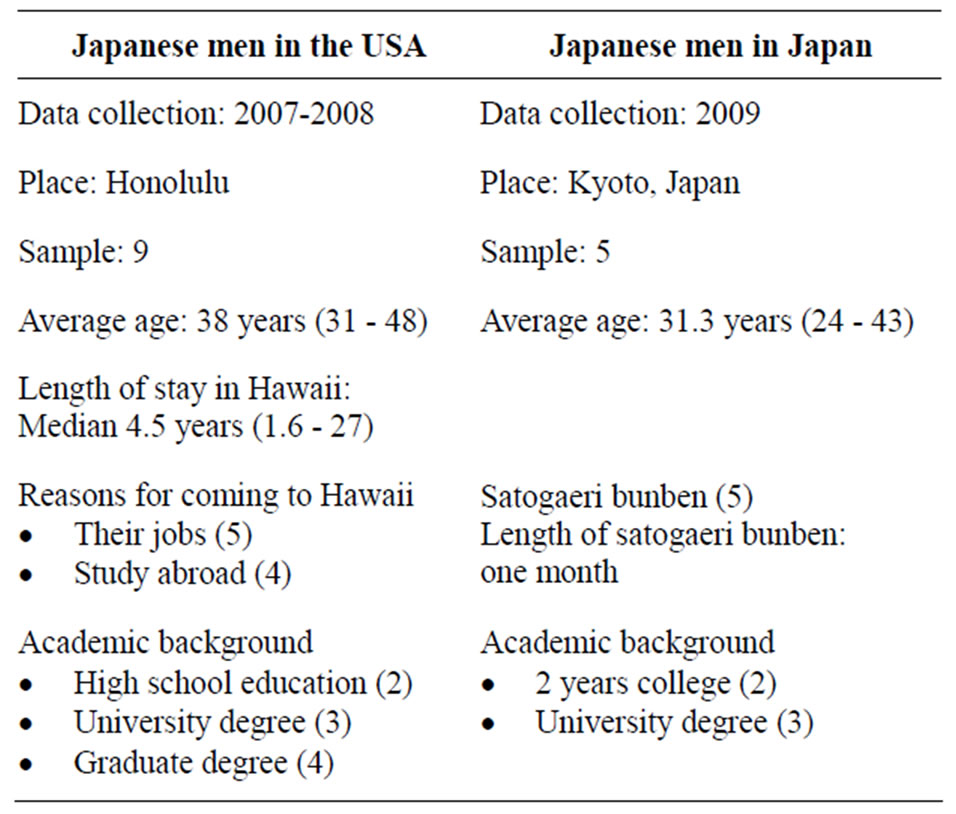

For Japanese men in the United States, interviews were conducted in Honolulu. The sample size was 9. The average age was 38 years. The length of stay in Hawaii was 1.6 to 27 years. Reasons for coming to Hawaii and academic backgrounds are shown on Table 2. For Japanese men in Japan, interviews were conducted in Kyoto. The sample size was 5. The average age was 31.3 years, which is the average age for Japanese men to become fathers. Academic backgrounds are shown on Table 2. All the wives of participants in Japan practiced “satogaeri-bunben” for about one month.

By comparing the impact of parenthood on Japanese men in Japan and the United States, this study found unexpected emotional similarities and behavioral differences between the two groups. Emotional similarities involved the following: both groups of men felt a strong bond with their spouses having together experienced

Table 1. Data analysis steps of Colaizzi method.

Table 2. Profiles of both Japanese men in Japan and the USA.

childbirth for the first time, and both groups were also awed by the strength of their wives and came to hold a general respect for women who had gone through childbirth and parenting.

Despite feeling a closer to their spouses, both groups also recognized a strong bond between mother and baby, leading them to experience feelings of isolation. Other similarities include both groups being concerned about their wives’ emotional swings during their pregnancy. Finally, the men in both groups began to focus more on their wives and babies than themselves. The followings are among the most significant statements.

“After giving birth, I always think that fathers can never take the place of mothers, even if they have the strongest will. It was a very good opportunity for me to attend childbirth. I now am able to respect my wife and even other women who give birth.”

“It is precious for me to have overcome a difficult situation (during pregnancy, childbirth and child rearing) with my wife, isn’t it? By having my own child, I realized that I grew from a child into a real adult.”

Another significant statement for their wives’ emotional swings:

“She doesn’t have anyone to talk to during the day. My son could not speak yet. I have to become an outlet for her complaints when I return home because she has been alone all day.”

Fathers who responded with such comments tried to listen to their wives’ complaints and make them feel comfortable at the end of day by giving them emotional support.

Differences between the two groups of men were also evident. In Japan, men live in a work-oriented society with only limited involvement with parenting. They typically rely on their own extended family. In particular, the maternal family is more willing to help with, for example, satogaeri-bunben. Men tended to be left out of the childbirth environment. After finishing satogaeri and returning to their own homes, women played the central role in family life as husbands were limited in the amount of time they could spend with their family. It was only on weekends when they could spend more time with their family at home. The followings are the most proper significant statements.

“On weekdays, I can see only his cute sleeping face before going to work. When I return to home, it is a time for him to sleep. As a result, at the most, I can look at him and hug him only shortly.”

“If we don’t have support from our family and others, I have to be involved myself into child rearing. We are so happy to now have such a comfortable environment with their support.”

On the other hand, in the United States, men live in a family-oriented society. Men were more involved in taking care of their families because of limited support from their extended families and due to the practice of early discharge from hospitals. They supported their family by taking parental leave and also working more flexible hours. For this reason, they could spend more time with their families at home. Women were totally dependent on their husbands, with the result that men actually played central roles in their families. The following are proper significant statements.

“It is very good for me to be living in Hawaii, to work a flexible schedule and to also gain social support here, some men also take parental leave. It is a very nice society to be concerned with the welfare of a family”.

“It is normal here that co-workers go straight home after working. By following them, I became increasingly interested in my wife. So, I was able to spend the rest of the day with my family”.

4. DISCUSSION

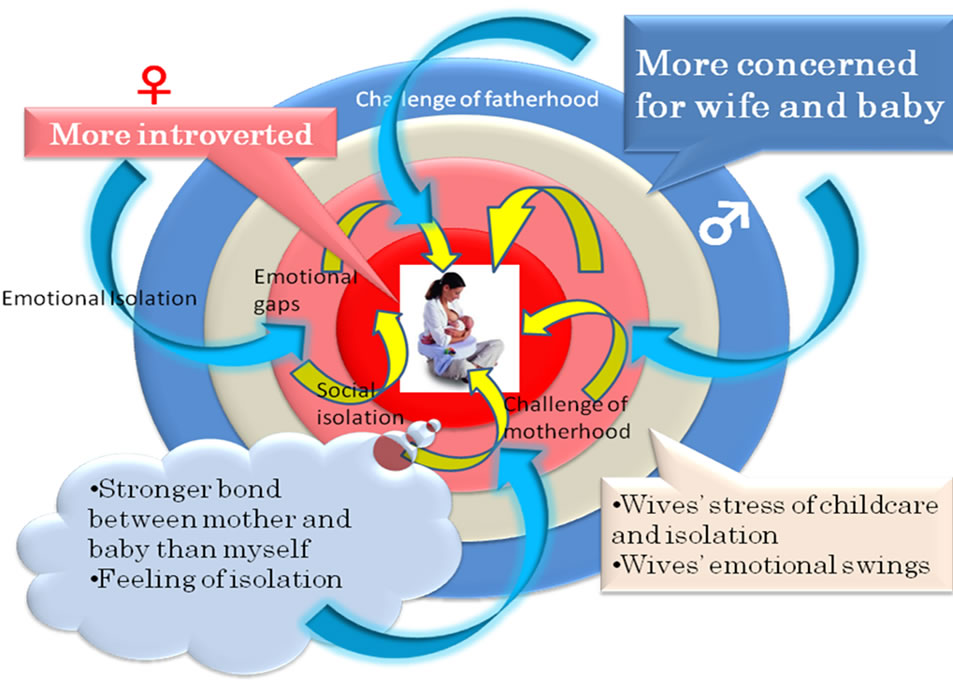

Figure 1 is a conceptual map of the emotional and behavioral differences between men and women. It shows that while women become more introverted during pregnancy and following childbirth [12], men become nervous with their wives’ emotional swings and the stress of childcare. In addition, while feeling at the time isolated from their families, they become increasingly concerned for wives and babies. As a result, even while feeling isolated men from both groups attempted to draw close to their wives and children.

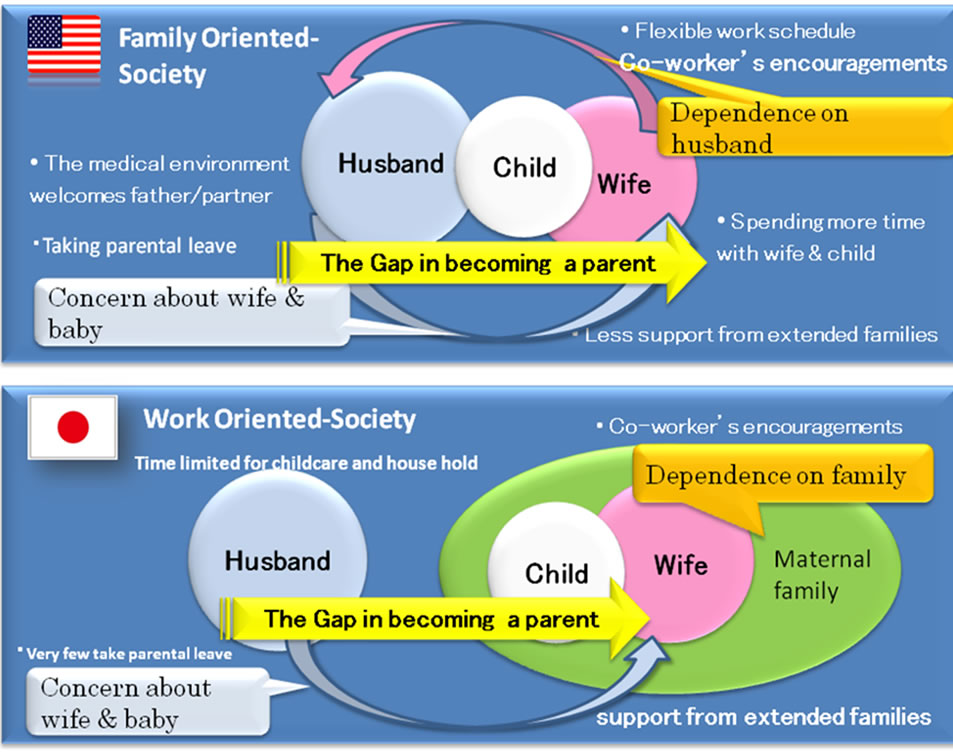

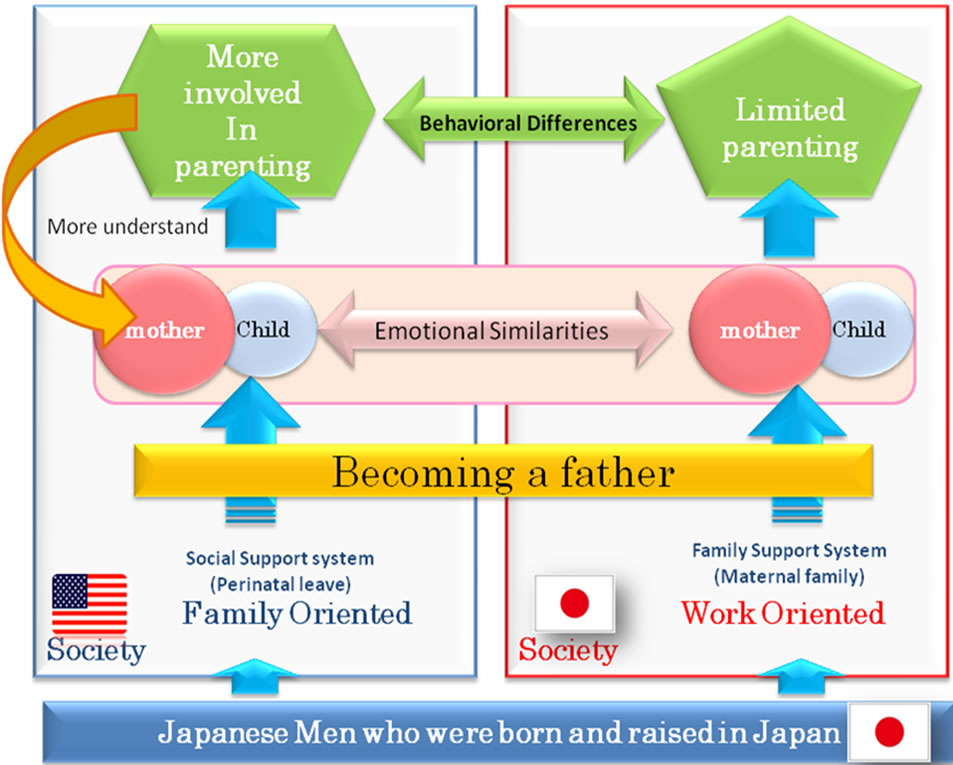

Figure 2 illustrates behavioral differences between the two groups of men. The differences between Japanese fathers in the United States and Japan are clear. Japanese wives in the United States relied on their husbands while

Figure 1. A conceptual map of the emotional and behavioral differences between men and women: while women become more introverted during pregnancy and following childbirth, men become increasingly concerned for wives and babies.

Figure 2. The different family relationships between Japan and the United States: Japanese wives in the United States relied on their husbands while Japanese wives in Japan relied on their maternal family members by social structure.

Figure 3. The different processes of becoming a father between two groups Japanese men who lived in the United States were more involved in parenting. Therefore, they had a better understanding of the stress of childcare.

Japanese wives in Japan relied on their maternal family members. This and other differences are tied to social structure (family-oriented society vs. work-oriented society), healthcare systems (early discharge from hospital), family structure (support system), and childbirth customs (satogaeri-bunben) [13].

Figure 3 shows how Japanese men who were born and raised in Japan followed different behavior patterns when living in the United States. When both groups became fathers, they felt similarly concerned about their wives and babies, but showed different behavior depending on the country where they were living. Japanese men who lived in the United States were more involved in parenting. Therefore, they had a better understanding of the stress of childcare through their involvement with their children, and they recognized that parenting should be shared with their wives because it contributes not only to producing a richer life, but also reduces their wives’ stress [14].

5. CONCLUSION

The behavioral differences were clearly evident between Japanese fathers in Japan and the United States, with systems of social support and social structure easily changing gender roles and behaviors. It is important that healthcare providers emphasize to expectant parents the satisfaction of sharing parenting by supporting each other and establishing their new life, together.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Japanese men who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- Shinagawa, N., Nomura, Y. and Katagiri, S. (1978) Social and medical discussion on Satogaeri Bunben. Nihonishikai Zasshi, 80, 351-355.

- Iwata, H. (2003) A concept analysis of the role of father hood: a Japanese perspective. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 14, 297-304. doi:10.1177/1043659603256456

- Aono, M., Takagi, K., Sasagawa, I., et al. (2005) Effect of witnessing the births of their children on husbands’ emotions—A comparison between two groups of husbands: those who did and did not witness the births. Boseieisei, 45, 530-539.

- Nakashima, M. and Uchinohama, H. (2007) The awareness of husbands after being present at their child-birth. Boseieisei, 48, 82-89.

- Shinozawa, M., Ishida, S. and Hagihara, Y. (2007) Aware ness of paternal childrearing during the early postpartum period—Mothers’ expectation to their partners, views of gender roles and parenting class. Boseieisei, 47, 582-589.

- Kaplan, W. (2004) New dads in labors: An opportunity for involvement. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 19, 14-17.

- Genesoni, L. and Tallandini, M.A. (2009) Men’s psychological transition to fatherhood: An analysis of the literature, 1989-2008. Birth, 36, 305-318. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00358.x

- Moustakas, C.E. (2004) Phenomenological research methods. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Taniguchi, H. and Magnussen, L. (2009) Expatriate Japanese women’s growth and transformation through child birth in Hawaii, USA. Nursing and Health Sciences, 11, 271-276. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00452.x

- Morse, J. and Richards, L. (2002) Read me first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods. Saga publications, inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Colaizzi, P.F. (1978) Psychological research as a phenomenologist views it. In: Valle, R.S. and King, M., Eds., Existential-Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology, Oxford University Press, New York, 48-71.

- Fontenot, H.B. (2007) Transition and adaptation to adoptive motherhood. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 36, 175-182. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00134.x

- Castillo, J., Welch, G. and Sarver, C. (2010) Fathering: The relationship between father’s residence, father’s sociodemographic characteristics, and father. Maternal Child Health Journal, 15, 1342-1349. doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0684-6

- Premberg, A., Hellström, A.-L. and Berg, M. (2008) Experiences of the first year as father. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22, 56-63. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00584.x