Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Vol.3 No.1A(2013), Article ID:27696,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojog.2013.31A033

Reproductive health needs of physical handicapped females in Kinshasa, DR Congo

![]()

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Clinics, Kinshasa, DR Congo

Email: *btanduumba@yahoo.fr

Received 12 November 2012; revised 14 December 2012; accepted 22 December 2012

Keywords: Sex and Reproduction; Disabled Women in Kinshasa; Psycho-Social Limitations

ABSTRACT

Objective: Our study is intended to evaluate mobility impairment’s level in adult females, their sociodemographic status, knowledge, and practices related to reproductive health in order to provide healthcare givers and policy makers with tools to meet appropriate needs of these vulnerable persons in Kinshasa, DR Congo. Study design: A cross-sectional descriptive study from March 20th 2012 throughout July 20th 2012 concerned 138 physical (non mental) disabled attendees of 7 centers for disabled adults in Kinshasa, DR Congo. Concerns about extend of the disability focused on parts of the body concerned, functional capacity (self walking, crutches, prosthesis, wheelchairs) and manual freedom. Participants were interviewed using open-ended questions about sociodemographic status, knowledge, and practices related to reproductive health. Issues concerned included age at menarche, age at first sex experience, marital status, education level, employment status, obstetric history, sex abuse, birth control and sexual transmitted diseases. For statistic analysis OR (CI at 95%) was calculated to seek for possible association between physical impairment and parturition’s characteristics. Results: The mean age of the study group (31.1 ± 5.7 years) ranged from 15 to 40 years. Most were affected by legs and the majority (69.1%) needed crutches or wheelchair for moving. Only 21 (15.2%) were married, most (15) of them with a disabled colleague. Mean parity and gravidity were 2.78 ± 2.3 (range 0 - 11) and 3.4 ± 2.5 (range 0 - 12), respectively. Sex experience was initiated at 17.5 ± 3.7 years (range of 12 - 35), 13 (9.4%) had experienced rape, and 37 (26.8%) had (illegally) aborted. Of the 117 women who had had a child 82 (70.7%) had vaginal delivery. In 24 of 34 cesarean sections fetopelvic disproportion or protracted pelvis was the main indication (68.6%), the risk for cesarean section being somewhat related to involvement of 2 legs. Data concerning the issue of knowledge and practices related to reproductive health were very limited and unreliable. Conclusion: Based on the age at menarche, at first intercourse and having had child reflect obvious interest of disabled in sex and reproduction, even if unmarried. Their limited information on reproductive health education results in unplanned pregnancy, unsafe abortion and risk for HIV and other sexual transmitted diseases. The rate of vaginal delivery is likely to redeem own perception on their health status. This could be basis for adhesion to specific programs devoted to physical, psychological, and social limitations.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [1] persons with disabilities are those with “long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others”. As such, at least 10 per cent of the world’s population are concerned, the large majority (80%) living in developing countries [1]. Although reports have been increasing on their ability to have children [2-4], stigma on their sexual interest and fear to see them pregnant persist, resulting in restriction of information on birth control and other reproductive health issues [5]. This in turn has increased their risk for unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions, sexual abuse, sexually transmitted infection, including HIV contamination, and exclusion from cervical screening options [5-8]. African literature dealing with these challenges is very limited. The 8 participants studied in the Northwest Region of Cameroon by Bremer et al. [9] had poor knowledge of reproductive health issues, many had experienced unplanned pregnancy and pregnancy was often feared. In their investigation of the knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning reproductive health among women with physical disabilities in Senegal Sow [8] reported similar limits concerning HIV and other sexually transmitted infections along with contraceptives methods. Our study is intended to evaluate mobility impairment’s level in adult females, their socio-demographic status, knowledge, and practices related to reproductive health in order to provide healthcare givers and policy makers with tools to meet appropriate needs of these vulnerable persons in Kinshasa, DR Congo.

2. METHODS

A cross-sectional descriptive study approved by the institutional board of our faculty of medicine was conducted from March 20th 2012 throughout July 20th 2012. It concerned 7 centers that serve for housing or professional support for disabled adults in Kinshasa, DR Congo, namely Victoire, Kalembelembe, Gombe, Limete, Lac Moero, N’djili and Sainte Anne. We added Ngobila beach (the Kinshasa side of the Kinshasa-Brazzaville river-crossing) and the boulevard of June 30th, the two highest concentrations of begging in Kinshasa. All disabled attendees with physical impairment that limits mobility or potential handling of baby were consecutively contacted for consent to participate into the study. Mental disabled and women in menopause were excluded. After explanation of the study very few declined. Assuming a prevalence of 5% handicapped people in DR Congo [10], sample size was calculated as 138. Concerns about extend of the disability focused on parts of the body concerned, functional capacity (self walking, crutches, prosthesis, wheelchairs) and manual freedom. Participants were interviewed using open-ended questions about socio-demographic status, knowledge, and practices related to reproductive health. Issues concerned included age at first sex experience, marital status, education level, employment status, obstetric history, sex abuse, birth control, sexual transmitted diseases and cancer screening options.

For statistic analysis OR (CI at 95%) was calculated to seek for possible association between physical impairment and parturition’s characteristics.

3. RESULTS

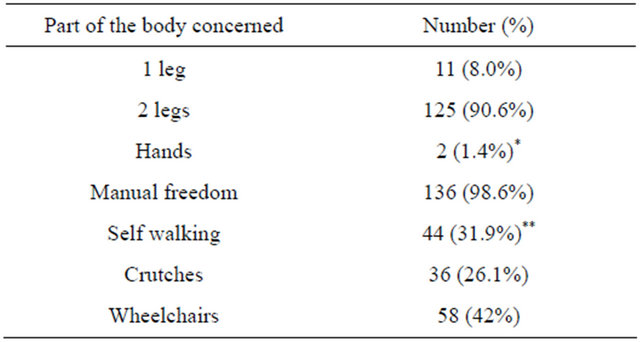

The mean age of the study group (31.1 ± 5.7) ranged from 15 to 40 years. Extend of the disability is presented in Table 1 where it can be seen that legs were the main part of the body concerned by handicap and the majority (69.1%) needed crutches or wheelchair for moving. Only 2 women had hand disability likely to limit baby’s handling.

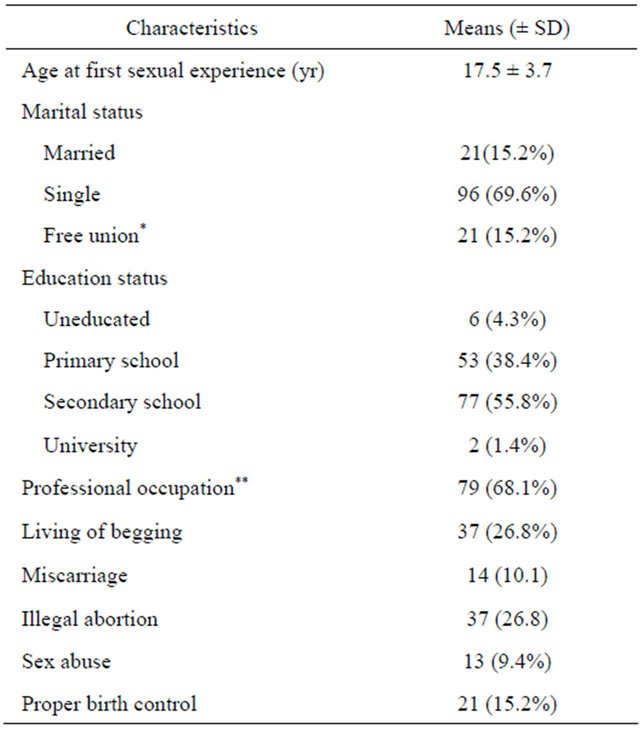

As of socio-demographic conditions (Table 2) only 21 (15.2%) were married, most (15) of them with a disabled colleague. Mean parity and gravidity were 2.78 ± 2.3

Table 1. Physical conditions and mobility of the study groups.

*Both leg and homolateral arm; **Whose 1 with prothesis.

Table 2. General characteristics of study group (N = 138).

*Whose 15 with disabled colleagues; **Whose 28 artists, 41 traders and 25 tailors.

(range 0 - 11) and 3.4 ± 2.5 (range 0 - 12), respectively. Other characteristics are presented in Table 2: 79 (57.2%) were educated and the majority (79 = 68.1%) had a job. Sex experience was reportedly begun at 17.5 ± 3.7 years (range of 12 - 35), 13 (9.4%) had experienced rape, and 37 (26.8%) had (illegally) aborted.

Of the 117 women who had had a child 82 (70.7%) had vaginal delivery. In 24 of 35 cesarean sections fetopelvic disproportion or protracted pelvis was the main indication (68.6%), followed by unknown causes (8 = 22.9%) and macrosomia (6 = 17.1%). Seeking for influence of disabilities on mode of delivery (Table 3) showed that risk for cesarean section and fetopelvic disproportion were 1.5 time and 4 times higher respectively in association with involvement of two legs than one, although

Table 3. Influence of disabilities on way of delivery.

*= Containing 1.

the confidence interval contained 1.

Knowledge and practices related to reproductive health were very limited. The majority i.e. 97 (70.3%) had heard of contraception but only 67 (48.5%) had been offered proper information, the main source being chatting with unqualified colleagues (75/97 = 54%).The correct mode of HIV transmission was known by 125 (90.6%) mostly (113 = 81.9%) from comrades, 9 (6.5%) from media and 6 (4.3%) from campaigns. However, 31 (22.5%) were ignorant of the way to prevent contamination, while 29.6% had heard of HIV as a curable illness.

Names of other sexual transmitted diseases were unknown and their symptoms identified as vulvovaginal pruritus alone (76 = 55.1%) or associated with hypogastralgia (14 = 10.1%) or leucorrhea (16 = 11.6%). The most cited modes of contamination were sexual contact (74 = 53.6%) and sharing textile towels (28 = 20.3%). Although a large portion (74.6%) of participants were informed of the existence of gynecologic cancers, nobody recognized to be informed of breast and cervical cancer screening options. Concerning access to care of handicapped women, 23 (16.7%) claimed not to have ever been properly catered for.

4. DISCUSSION

Reproductive health of disabled persons strongly depends on attitudinal and environmental trends of the society to reverse stigmas that have blinded their interest in sex and reproduction and confined these persons in ignorance [1-9,11-13]. As reported for the general population of Kinshasa [10] most of our sample had had their first intercourse at 17.5 years and the proportion (84.8%) ever having given birth at the time of the study reflects their interest in sex and reproduction. The estimate of 63.8% not married at the mean age of 31 years illustrates a poor potential of marriage that can be owed to reluctance of valid counterparts due to limitations in major household activities. This pushes some (15.2%) to live with disabled comrades. Their limited information on contraception and other important topics of reproductive health education that has been reported elsewhere in Africa [2,8] is basis for unplanned pregnancy, some of women (26.8%) having terminated their pregnancies into illegal and unsafe abortion. Sex abuse and restriction in information on HIV and other sexual transmitted diseases that are common among authors [2,8] are additional challenges to accompany reproductive life of disabled women [11-13]. As of low relevance of information on gynecologic cancer screening it probably reflects that of the overall gynecologic population in our setting. The rate of educated (57.2%) combined with the professional status of most of them (only 26.8% living of begging) are to be considered as assets in comparison with usually alleged financial concerns of disabled women [8]. So, adhesion of disabled women to specific programs likely to provide proper education can be improved by awareness to physical, psychological, and social limitations.

In comparison with developed countries the issue of pregnancy that proceeds in disabled persons until confinement probably sounds more crucial in Africa due to pronatalism of populations. Everyone is expected to reproduce. Yet, fear to see disabled women pregnant is a recurrent issue in respect with challenges posed by difficulties to take a proper position (legs wide open) during parturition/post-partum, specific care necessitated by hemorrhage management and inability to handle the baby in case of limited use of hands [14]. Although Lee and Oh in South Korea [3] reported that disabled women were as likely as valid persons to care for their children, they cannot achieve such huge needs without adequate psychological support and specific family’s involvement [14]. Additional source of fear of pregnancy could also come from potential threat of certain disabilities on child: transmission of an inherited disability, toxic effect of medicines needed for the maternal disability etc. These issues not investigated in our study should be properly addressed by obstetricians and gynecologists.

Our study did not address the question of fear but the rate of vaginal delivery of our sample (70.7%) can be viewed positively and exploited to redeem own perception of disabled on their motherhood capacity. One woman of our series had had 11 deliveries, a performance even scarce in valid, although not recommended in anyone. Risk of cesarean delivery in disabled is to be considered in accordance with maternal pelvis, as it has been observed in the literature [12,13].

Although most of disabled persons live in developing countries [1] only few articles can be found on reproductive health needs of physical handicapped females in Africa. In comparison with previous studies this one added specific physical (mobility impairment’s level) and obstetric/gynecological characteristics for better evaluating relationships between disability and sociodemographic status, knowledge, and practices related to reproductive health. The main weakness of the study might be lack of a control group made of valid women to make more obvious particularities of disabled in issues addressed.

REFERENCES

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. UN Development Programme (UNDP). http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/facts.shtml

- Trani, J.F., Browne, J., Kett, M., Bah, O., Morlai, T., Bailey, N. and Groce, N. (2011) Access to health care, reproductive health and disability: A large scale survey in Sierra Leone. Social Sciences in Medicine, 73, 1477-1489. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.040

- Lee, E.O. and Oh, H. (2005) A wise wife and good mother: Reproductive health and maternity among women with disability in South Korea. Sexuality and Disability, 23, 121-144. doi:10.1007/s11195-005-6728-y

- Lipson, J.G. (2000) Pregnancy, birth, and disability: Women’s health care experiences. Health Care for Women International, 21, 11-26. doi:10.1080/073993300245375

- Schopp, L.H., Sanford, T.C., Hagglund, K.J., Gay, J.W. and Coatney, M.A. (2002) Removing service barriers for women with physical disabilities: promoting accessibility in the gynecologic care setting. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 47, 74-79. doi:10.1016/S1526-9523(02)00216-7

- Vanneste, G. (2004) A crucial implication: Diversifying CBR projects towards AIDS related services. In: Symposium: HIV/AIDS and Disability—A Global Challenge. Frankfurt am Main, Iko Verlag.

- Africa Campaign on Disability and HIV & AIDS: Kampala Declaration on Disability and HIV & AIDS (2008) Declaration on disability and HIV. http://www.dcdd.nl/data/1208782834413_Kampala

- Sow, A. (2006) Reproductive health in disabled women. Mémoire DEA. Cheik Anta Diop University, Dakar, 1- 70.

- Bremer, K., Cockburn, L. and Ruth, A. (2010) Reproductive health experiences among women with physical disabilities in the Northwest Region of Cameroon. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 108, 211-213. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.10.008

- Ulloa, A., Katz, F. and Kekeh, N. (2009) Democratic Republic of the Congo: A study of binding constraints. EDS-RDC. http://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/drodrik/Growth

- Hassoueh-Phillips, D. and Curry, M.A. (2002) Abuse of women with disabilities: State of the science. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 45, 96-104. doi:10.1177/003435520204500204

- Chang, J.C., Martin, S.L., Moracco, K.E., Dulli, L., Scandlin, D., Loucks-Sorrel, M.B., et al. (2003) Helping women with disabilities and domestic violence: Strategies, limitations, and challenges of domestic violence programs and services. Journal of Women’s Health, 12, 699- 708. doi:10.1089/154099903322404348

- Cramer, E.P., Gilson, S.F. and DePoy, E. (2003) Women with disabilities and experiences of abuse. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 7, 183-199. doi:10.1300/J137v07n03_11

- Rogers, J. (2005) The disabled woman’s guide to pregnancy and birth. Demos Health Publishing, New York.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.