Open Journal of Statistics

Vol.05 No.04(2015), Article ID:57369,22 pages

10.4236/ojs.2015.54033

Linear Dimension Reduction for Multiple Heteroscedastic Multivariate Normal Populations

Songthip T. Ounpraseuth1, Phil D. Young2, Johanna S. van Zyl2, Tyler W. Nelson2, Dean M. Young2

1Department of Biostatistics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AK, USA

2Department of Statistical Science, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA

Email: stounpraseuth@uams.edu, philip_young@baylor.edu, tyler_nelson@baylor.edu, johanna_vanzyl@baylor.edu, dean_young@baylor.edu

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 16 April 2015; accepted 19 June 2015; published 24 June 2015

ABSTRACT

For the case where all multivariate normal parameters are known, we derive a new linear dimension reduction (LDR) method to determine a low-dimensional subspace that preserves or nearly preserves the original feature-space separation of the individual populations and the Bayes pro- bability of misclassification. We also give necessary and sufficient conditions which provide the smallest reduced dimension that essentially retains the Bayes probability of misclassification from the original full-dimensional space in the reduced space. Moreover, our new LDR procedure requires no computationally expensive optimization procedure. Finally, for the case where parameters are unknown, we devise a LDR method based on our new theorem and compare our LDR method with three competing LDR methods using Monte Carlo simulations and a parametric bootstrap based on real data.

Keywords:

Linear Transformation, Bayes Classification, Feature Extraction, Probability of Misclassification

1. Introduction

The fact that the Bayes probability of misclassification (BPMC) of a statistical classification rule does not increase as the dimension or feature space increases, provided the class-conditional probability densities are known, is well-known. However, in practice when parameters are estimated and the feature-space dimension is large relative to the training-sample sizes, the performance or efficacy of a sample discriminant rule may be considerably degraded. This phenomenon gives rise to a paradoxical behavior that [1] has called the curse of dimensionality.

An exact relationship between the expected probability of misclassification (EPMC), training-sample sizes, feature-space dimension, and actual parameters of the class-conditional densities is challenging to obtain. In general, as the classifier becomes more complex, the ratio of sample size to dimensionality must increase at an exponential rate to avoid the curse of dimensionality. The authors [2] have suggested a ratio of at least ten times as many training samples per class as the feature dimension increases. Hence, as the number of feature variables p becomes large relative to the training-sample sizes ,

,  , where m is the number of classes, one might wish to use a smaller number of the feature variables to improve the classifier performance or computational efficiency. This approach is called feature subset selection.

, where m is the number of classes, one might wish to use a smaller number of the feature variables to improve the classifier performance or computational efficiency. This approach is called feature subset selection.

Another effective approach to obtain a reduced dimension to avoid the curse of dimensionality is linear dimension reduction (LDR). Perhaps the most well-known LDR procedure for the m-class problem is linear discriminant analysis (LDA) from [3] , which is a generalization of the linear discriminant function (LDF) derived in [4] for the case . The LDA LDR method determines a vector

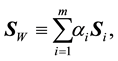

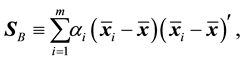

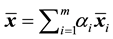

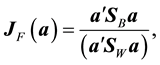

. The LDA LDR method determines a vector  that maximizes the ratio of between- class scatter to average within-class scatter in the lower-dimensional space. The sample within-class scatter matrix is

that maximizes the ratio of between- class scatter to average within-class scatter in the lower-dimensional space. The sample within-class scatter matrix is

(1)

(1)

where  is the estimated sample covariance matrix for the ith class, and the sample between-class scatter matrix is

is the estimated sample covariance matrix for the ith class, and the sample between-class scatter matrix is

(2)

(2)

where  is the sample mean vector for class

is the sample mean vector for class ,

,  is its a priori probability of class membership,

is its a priori probability of class membership,  is the estimated overall mean, and

is the estimated overall mean, and . For

. For  with

with , [4] determined the vector

, [4] determined the vector  that maximizes the criterion function

that maximizes the criterion function

which is achieved by an eigenvalue decomposition of

Extensions of LDA that incorporate information on the differences in covariance matrices are known as heteroscedastic linear dimension reduction (HLDR) methods. The authors [8] have proposed an eigenvalue-based HLDR approach for

Using results by [13] that characterize linear sufficient statistics for multivariate normal distributions, we develop an explicit LDR matrix

where

Moreover, we use Monte Carlo simulations to compare the classification efficacy of the BE method, sliced inverse regression (SIR), and sliced average variance estimation (SAVE) found in [14] -[16] , respectively, with the SY method.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We begin with a brief introduction to the Bayes quadratic classifier in Section 2 and introduce some preliminary results that we use to prove our new LDR method in Section 3. In Section 4, we provide conditions under which the Bayes quadratic classification rule is preserved in the low-dimensional space and derive a new LDR matrix. We establish a SVD-based approximation to our LDR procedure along with an example of low-dimensional graphical representations in Section 5. We describe the four LDR methods that we compare using Monte Carlo simulations in Section 6. We present five Monte Carlo simulations in which we compare the competing LDR procedures for various population parameter configurations in Section 7. In Section 8, we compare the four methods using bootstrap simulations for a real data example, and, finally, we offer a few concluding remarks in Section 9.

2. The Bayes Quadratic Classifier

The Bayesian statistical classifier discriminates based on the probability density functions

the Bayes classifier assigns

This decision rule partitions the measurement or feature space into m disjoint regions

One can re-express the Bayes classification as the following:

Assign

This decision rule is known as the Bayes’ classification rule. Let

The Bayes decision rule (4) is to classify the unlabeled observation

3. Preliminary Results

The following notation will be used throughout the remainder of the paper. We let

The proof of the main result for the derivation of our new LDR method requires the following notation and lemmas. Let

where

(i)

(ii)

We now state and prove three lemmas that we use in the proof of our main result.

Lemma 1 For

(a)

(b)

(c)

Proof. Part (a) follows from the fact that

Lemma 2 For

Proof. Because

Lemma 3 Let

(a)

(b)

(c)

Proof. The proof of part (a) of Lemma 3 follows from (i), and we have that

for each

4. Linear Dimension Reduction for Multiple Heteroscedastic Nonsingular Normal Populations

We now derive a new LDR method that is motivated by results on linear sufficient statistics derived by [13] and by a linear feature selection theorem given in [17] . The theorem provides necessary and sufficient conditions for which a low-dimensional linear transformation of the original data will preserve the BPMC in the original feature space. Also, the theorem provides a representation of the LDR matrix.

Theorem 1 Let

Finally, let

Proof. Let

where

Recall that for

Therefore, the original p-variate Bayes classification assignment is preserved by the linear transformation

Theorem 1 is important in that if its conditions hold, we obtain a LDR matrix for the reduced q-dimensional subspace such that the BPMC in the q-dimensional space is equal to the BPMC for the original p-dimensional feature space. In other words, provided the conditions in Theorem 1 hold, we have that the LDR matrix

With the following corollary, we demonstrate that for two multivariate normal populations such that

Corollary 1 Assuming we have two multivariate normal populations

Proof. The proof is immediate from (7).

5. Low-Dimensional Graphical Representations for Heteroscedastic Multivariate Normal Populations

5.1. Low-Dimensional LDR Using the SVD

If

One method of obtaining an r-dimensional LDR matrix,

Theorem 2 Let

where

Furthermore,

Using Theorems 1 and 2, we now construct a linear transformation for projecting high-dimensional data onto a low-dimensional subspace when all class distribution parameters are known. Let

is a rank-r approximation of

We next provide an example to demonstrate the efficacy of Theorems 1 and 2 to determine low-dimensional representations for multiple multivariate normal populations with known mean vectors and covariance matrices. In the example, we display the simplicity of Theorem 1 to formulate a low-dimensional representation for three populations

5.2. Example

Consider the configuration

We have

Using Theorem 1, we have that an optimal two-dimensional representation space is

The optimal two-dimensional ellipsoidal representation is shown in Figure 1.

We can also determine a one-dimensional representation of the three multivariate normal populations through application of the SVD described in Theorem 2 applied to the matrix M given in (7). A one-dimensional representation space is column one of the matrix F in (8), and the graphical representation of this configuration of univariate normal densities is depicted in Figure 2.

6. Four LDR Methods for Statistical Discrimination

In this section, we present and describe the four LDR methods that we wish to compare and contrast in Sections 7 and 8.

Figure 1. The optimal two-dimensional representation for normal densities from the example in Section 5.2.

Figure 2. The optimal one-dimensional representation for normal densities from the example in Section 5.2.

6.1. The SY Method

In Theorem 1, we assume the parameters

provided

Thus, using the SVD, we let

with

Provided

6.2. The BE Method

A second LDR method presented by [14] is

for

The LDR matrix derived in [14] , which we refer to as the BE matrix, was also obtained when we determined low-rank approximation to

with

The BE LDR approach is based on the rotated differences in the means. The LDR matrix (10) uses a type of pooled covariance matrix estimator for the precision matrices. However, the BE method does not incorporate all of the information contained in the different individual covariance matrices. Another disadvantage of the BE LDR approach is that it is limited to a reduced dimension that depends on the number of classes, m. For

6.3. Sliced Inverse Regression (SIR)

The next LDR method we consider is sliced inverse regression (SIR), which was proposed in [16] . Assuming all population parameters are known, we first define

where

where

6.4. Sliced Average Variance Estimation (SAVE)

The last LDR method we consider is sliced average variance estimation (SAVE), which has been proposed in

[19] -[20] . The SAVE method uses the

where

where,

7. A Monte Carlo Comparison of Four LDR Methods for Statistical Classification

Here, we compare our new SY LDR method derived above to the BE, SIR, and SAVE LDR methods. Specifically, we evaluate the classification efficacy in terms of the EPMC for the SY, BE, SIR, and SAVE LDR methods using Monte Carlo simulations for five different configurations of multivariate normal populations with

For the SY and SAVE LDR approaches, we reduce the dimension to

The five Monte Carlo simulations were generated using the programming language R. Table 1 gives a description of the number of populations and the theoretically optimal rank of the four LDR indices for each configuration. In Figures 3-7, we display the corresponding EPMCs of the four competing LDR methods for the various population configurations and values of

7.1. Configuration 1: m = 2 with Moderately Different Covariance Matrices

The first population configuration we examined was composed of two multivariate normal populations

Table 1. A description of Monte Carlo simulation parametric configurations and singular values in Section 2 with unequal covariance matrices and

Figure 3. Simulation results from Section 7.1. The horizontal bar in each graph represents the

Figure 4. Simulation results from Configuration 2. The horizontal bar in each graph represents the

Figure 5. Simulation results from Section 7.3. The horizontal bar in each graph represents the

and

Figure 6. Simulation results from Configuration 4. The horizontal bar in each graph represents the

Figure 7. Simulation results from Section 7.5. The horizontal bar in each graph represents the

Here,

singular values of

When

dimensional subspaces. Not surprisingly, for

and for

In addition, the SIR LDR method did not utilize discriminatory information contained in the differences of the covariance matrices when

7.2. Configuration 2: m = 3 with Two Similar Covariance Matrices and One Spherical Covariance Matrix

The second Monte Carlo simulation used a configuration with the three multivariate normal populations

Table 2. Summary of singular values for the four competing LDR methods for Configuration 1.

and

In this configuration, the population means are unequal but relatively close. Moreover,

As a result of markedly different covariance matrices, the BE and SIR LDR methods are not ideal because both methods aggregated the sample covariance matrices. The SY LDR method, however, attempts to estimate each individual covariance matrix for all three populations, and uses this information that yielded SY as the superior LDR procedure. Table 3 gives the singular values of each of the LDR methords considered here.

For the larger sample-size scenario,

Table 3. Summary of singular values for the four competing LDR methods applied to Configuration 2.

that

7.3. Configuration 3: m = 2 with Relatively Close Means and Different But Similar Covariance Matrices

In this configuration, we have

and

As in Configuration 1, we have that

For

7.4. Configuration 4: m = 3 with Two Similar Covariance Matrices Except for the First Two Dimensions

In this situation, we have three multivariate normal populations:

Table 4. Summary of singular values for the four competing LDR methods for Configuration 3.

where

and

For the fourth configuration, the covariance matrices are considerably different from one another, which benefits both the SY and SAVE LDR methods. Specifically, the SY LDR procedure uses information contained in the unequal covariance matrices to determine classificatory information contained in

This population configuration illustrated the fact that we cannot always choose

7.5. Configuration 5: m = 3 with Diverse Population Covariance Matrices

In Configuration 5, we have three multivariate normal populations:

with

Table 5. Summary of singular values for the four competing LDR methods for Configuration 4.

and

Here, we have three considerably different covariance matrices. For this population configuration, the SY method outperformed the three other LDR methods for the reduced dimensions

The BE and SIR LDR methods did not perform as well here because of the pooling of highly diverse estimated covariance matrices. While the SAVE LDR procedure was the least effective LDR method for

8. A Parametric Bootstrap Simulation

In the following parametric bootstrap simulation, we use a real dataset to obtain the population means and covariance matrices for three multivariate normal populations. The chosen dataset comes from the University of Califorina at Irvine Machine Learning Repository, which describes the diagnoses of cardiac Single Proton Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) images. Each patient in the study is classified into two categories: normal or abnormal. The dataset contains 267 SPECT image sets of patients. Each observation consists of 44 continuous features for each patient. However, for our simulation, we chose only ten of the 44 features. The ten selected features were F2R, F6R, F7S, F9S, F11R, F11S, F14S, F16R, F17R, and F19S. Hence, we performed the parametric bootstrap Monte Carlo simulation with two populations:

Table 6. Summary of singular values for the four competing LDR methods for Configuration 6.

and

For this dataset,

Figure 8 gives the EPMCs for the reduced dimensions 1, 2, and 3 for each of the LDR methods. In this exam- ple, a considerable amount of discriminatory information is contained in the covariance matrices, which are ex- tremely different. Hence, not surprisingly, neither the BE nor the SIR LDR methods performed well for

For

Table 7. Summary of singular values for the four competing LDR methods for the parametric bootstrap example.

Figure 8. Simulation results from Section 8. The horizontal bar in each graph represents the

9. Discussion

In this paper, while all population parameters are known, we have presented a simple and flexible algorithm for a low-dimensional representation of data from multiple multivariate normal populations with different parametric configurations. Also, we have given necessary and sufficient conditions for attaining the subspace of smallest dimension

We have presented several advantages of our proposed low-dimensional representation method. First, our method is not restricted to a one-dimensional representation regardless of the number of populations, unlike the transformation introduced by [14] . Second, our method allows for equal and unequal covariance structures. Third, the original feature dimension p does not significantly impact the computational complexity. Also, under certain conditions, one-dimensional representations of populations with unequal covariance structures can be accomplished without an appreciable increase in the EPMC.

Furthermore, we have derived a LDR method for realistic cases where the class population parameters are unknown and the linear sufficient matrix M in (7) must be estimated using training data. Using Monte Carlo simulation studies, we have compared the performance of the SY LDR method with three other LDR procedures derived by [14] [16] [19] . In the Monte Carlo simulation studies, we have demonstrated that the full-dimension EMPC can sometimes be decreased by implementing the SY LDR method when the training-sample size is small relative to the total number of estimated parameters.

Finally, we have extended our concept proposed in Theorem 1 through the application of the SVD given in Theorem 2 to cases where one might wish to considerably reduce the original feature dimension. Our new LDR approach can yield excellent results provided the population covariance matrices are sufficiently different.

References

- Bellman, R. (1961) Adaptive Control Processes: A Guide Tour. John Wiley, Princeton University, Princeton.

- Jain, A.K. and Chandrasekaran, B. (1982) Dimensionality and Sample Size Considerations in Pattern Recognition Practice. In: Krishnaiah, P.R. and Kanal, L.N., Eds., Handbook of Statistics, Volume 2, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 201-213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0169-7161(82)02042-2

- Rao, C.R. (1948) The Utilization of Multiple Measurements in Problems of Biological Classification. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 10, 159-203.

- Fisher, R.A. (1936) The Use of Multiple Measurements in Taxonomic Problems. Annals of Eugenics, 7, 179-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.1936.tb02137.x

- McLachlan, G.J. (1992) Discriminant Analysis and Statistical Pattern Recognition. John Wiley, New York. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471725293

- Decell, H.P. and Mayekar, S.M. (1977) Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data via the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 39, 1-38.

- Okada, T. and Tomita, S. (1984) An Extended Fisher Criterion for Feature Extraction―Malina’s Method and Its Problems. Electronics and Communications in Japan, 67, 10-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ecja.4400670603

- Loog, M. and Duin, P.W. (2004) Linear Dimensionality Reduction via a Heteroscedastic Extension of LDA: The Chernoff Criterion. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 26, 732-739. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2004.13

- Fukunaga, K. (1990) Introduction to Statistical Pattern Recognition. 2nd Edition, Academic Press, Boston.

- Hennig, C. (2004) Asymmetric Linear Dimension Reduction for Classification. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 13, 930-945. http://dx.doi.org/10.1198/106186004X12740

- Kumar, N. and Andreou, A.G. (1996) A Generalization of Linear Discriminant Analysis in a Maximum Likelihood Framework. Proceedings of the Joint Statistical Meeting.

- Young, D.M., Marco, V.R. and Odell, P.L. (1987) Quadratic Discrimination: Some Results on Optimal Low-Dimen- sional Representation. The Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 17, 307-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-3758(87)90122-4

- Peters, B.C., Redner, R. and Decell, H.P. (1978) Characterization of Linear Sufficient Statistics. Sankhya, 40, 303-309.

- Brunzell, H. and Eriksson, J. (2000) Feature Reduction for Classification of Multidimensional Data. Pattern Recognition, 33, 1741-1748. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0031-3203(99)00142-9

- Cook, R.D. and Weisberg, S. (1991) Discussion of “Sliced Inverse Regression for Dimension Reduction” by K.-C. Li. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 86, 328-332.

- Li, K.-C. (1991) Sliced Inverse Regression for Dimension Reduction. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 86, 316-327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1991.10475035

- Tubbs, J.D., Coberly, W.A. and Young, D.M. (1982) Linear Dimension Reduction and Bayes Classification with Unknown Population Parameters. Pattern Recognition, 15, 167-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0031-3203(82)90068-1

- Schervish, M.J. (19884) Linear Discrimination for Three Known Normal Populations. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 10, 167-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-3758(84)90068-5

- Cook, R.D. (2000) SAVE: A Method for Dimension Reduction and Graphics in Regression. Communications in Statistics―Theory and Methods, 29, 2109-2121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03610920008832598

- Cook, R.D. and Yin, X. (1991) Dimension Reduction and Visualization in Discriminant Analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Statistics, 43, 147-199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-842X.00164

- Vellila, S. (2012) A Note on the Structure of the Quadratic Subspace in Discriminant Analysis. Statistics and Probability Letters, 82, 739-747. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spl.2011.12.020