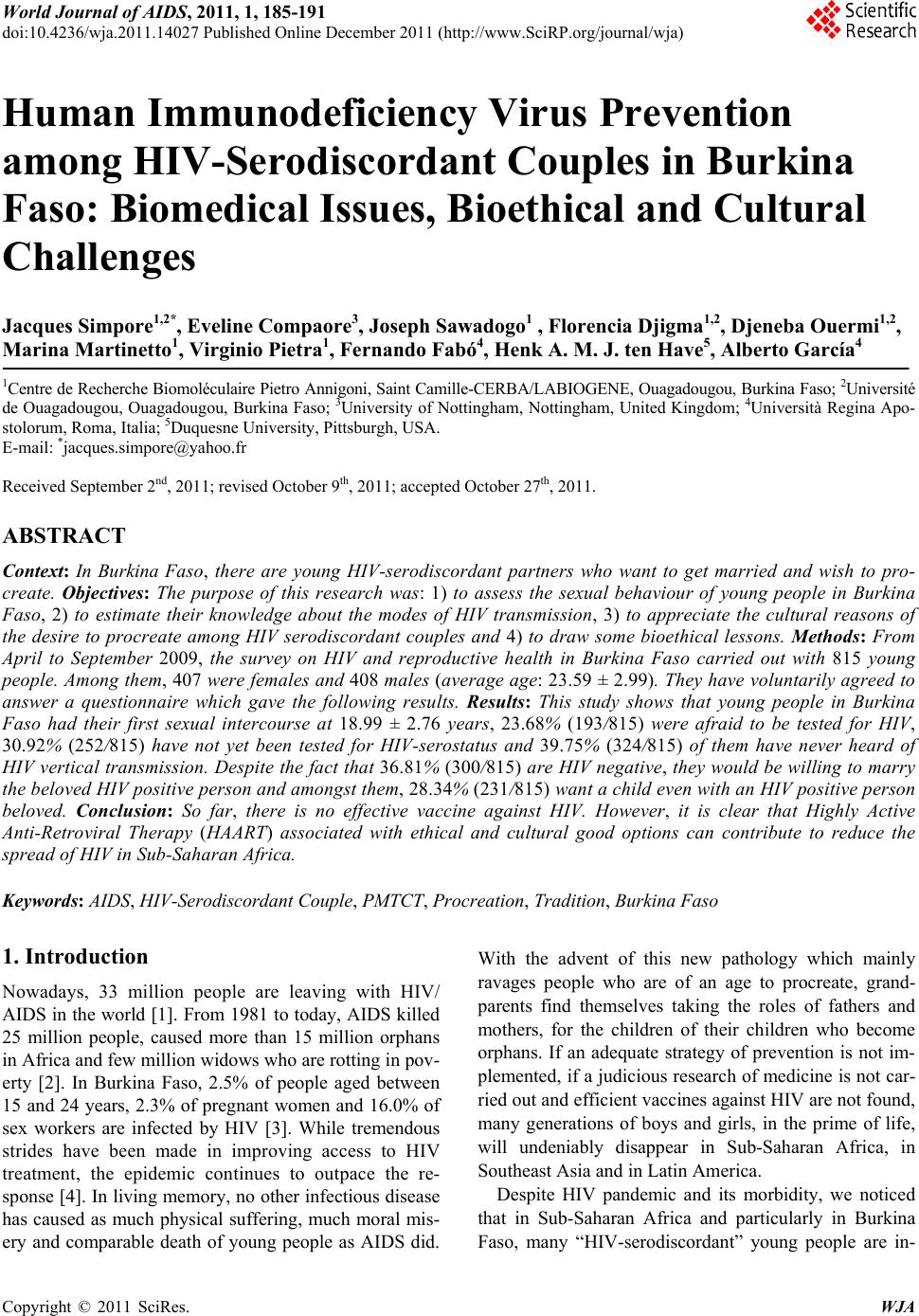

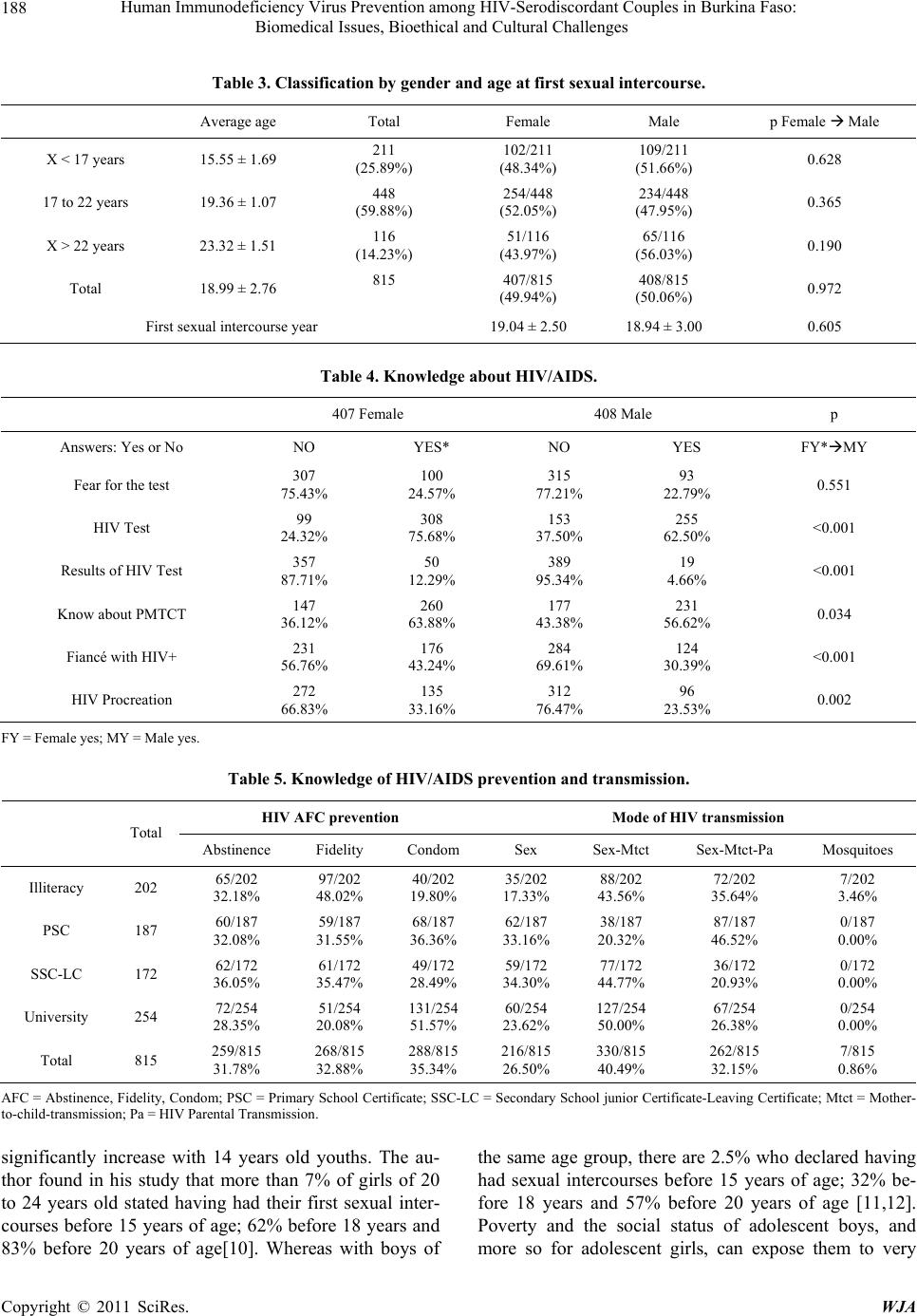

World Journal of AIDS, 2011, 1, 185-191 doi:10.4236/wja.2011.14027 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/wja) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA 185 Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention among HIV-Serodiscordant Couples in Burkina Faso: Biomedical Issues, Bioethical and Cultural Challenges Jacques Simpore1,2*, Eveline Compaore3, Joseph Sawadogo1 , Florencia Djigma1,2, Djeneba Ouermi1,2, Marina Martinetto1, Virginio Pietra1, Fernando Fabó4, Henk A. M. J. ten Have5, Alberto García4 1Centre de Recherche Biomoléculaire Pietro Annigoni, Saint Camille-CERBA/LABIOGENE, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; 2Université de Ouagadougou, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; 3University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom; 4Università Regina Apo- stolorum, Roma, Italia; 5Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, USA. E-mail: *jacques.simpore@yahoo.fr Received September 2nd, 2011; revised October 9th, 2011; accepted October 27th, 2011. ABSTRACT Context: In Burkina Faso, there are young HIV-serodiscordant partners who want to get married and wish to pro- create. Objectives: The purpose of this research was: 1) to assess the sexual behaviour of young people in Burkina Faso, 2) to estimate their knowledge about the modes of HIV transmission, 3) to appreciate the cultural reasons of the desire to procreate among HIV serodiscordant couples and 4) to draw some bioethical lessons. Methods: From April to September 2009, the survey on HIV and reproductive health in Burkina Faso carried out with 815 young people. Among them, 407 were females and 408 males (average age: 23.59 ± 2.99). They have voluntarily agreed to answer a questionnaire which gave the following results. Results: This study shows that young people in Burkina Faso had their first sexual intercourse at 18.99 ± 2.76 years, 23.68% (193/815) were afraid to be tested for HIV, 30.92% (252/815) have not yet been tested for HIV-serostatus and 39.75% (324/815) of them have never heard of HIV vertical transmission. Despite the fact that 36.81% (300/815) are HIV negative, th ey would be willing to marry the beloved HIV positive person and amongst them, 28.34% (231/815) want a child even with an HIV positive person beloved. Conclu s io n: So far, there is no effective vaccine against HIV. However, it is clear that Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy (HAART) associated with ethical and cultural good options can contribute to reduce the spread of HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. Keywords: AIDS, HIV-Serodiscordant Couple, PMTCT, Procreation, Tradition, Burkina Faso 1. Introduction Nowadays, 33 million people are leaving with HIV/ AIDS in the world [1]. From 1981 to today, AIDS killed 25 million people, caused more than 15 million orphans in Africa and few million widows who are rotting in pov- erty [2]. In Burkina Faso, 2.5% of people aged between 15 and 24 years, 2.3% of pregnant women and 16.0% of sex workers are infected by HIV [3]. While tremendous strides have been made in improving access to HIV treatment, the epidemic continues to outpace the re- sponse [4]. In living memory, no other infectious disease has caused as much physical suffering, much moral mis- ery and comparable death of young people as AIDS did. With the advent of this new pathology which mainly ravages people who are of an age to procreate, grand- parents find themselves taking the roles of fathers and mothers, for the children of their children who become orphans. If an adequate strategy of prevention is not im- plemented, if a judicious research of medicine is not car- ried out and efficient vaccines against HIV are not found, many generations of boys and girls, in the prime of life, will undeniably disappear in Sub-Saharan Africa, in Southeast Asia and in Latin America. Despite HIV pandemic and its morbidity, we noticed that in Sub-Saharan Africa and particularly in Burkina Faso, many “HIV-serodiscordant” young people are in-  Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention among HIV-Serodiscordant Couples in Burkina Faso: 186 Biomedical Issues, Bioethical and Cultural Challenges creasingly claiming the possibility to start a family. In addition, many HIV-serodiscordant partners wish to pro- create. This strong need of these couples, also called “HIV-serodifferent”, probably results from multifaceted elements: On the one hand, the increase in the number of HIV positives in the world and therefore the probability of meeting a HIV positive partner is very high; from the culture of some African societies, which are pronatalist and cannot allow a young girl or a young boy to live un- married, whatever her or his physical condition is. On the other hand, from therapeutic progresses in the treatment of HIV positives with multi antiretroviral therapies; from new technologies in reproductive biology which avoid the risks of infection through artificial in- semination [5]; and from the fact that under the Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy (HAART), some AIDS patients return to their professional activities, which they thought lost forever, develop projects and think with great hope about the future. Indeed, thanks to the ad- vancement of medicine, AIDS could become, in a near future, even in Sub-Saharan Africa, just a simple chronic affection [6,7]. The present study, the objective of which is the pre- vention of the transmission of HIV, intends: 1) to assess the sexual behaviour of young people in Burkina Faso, 2) to estimate their knowledge about the modes of HIV transmission, 3) to appreciate the cultural reasons of the desire to procreate among HIV serodiscordant couples and 4) to draw some bioethical lessons. 2. Method From April to September 2009, we have carried out a survey with 815 people from 18 to 32 years old who have been casually selected in public places in the city of Ouagadougou: at the markets, on the streets and at the university. These people were in average 23.59 ± 2.99 years old. Among them 407 were females and 408 males. They voluntarily accepted to answer our questionnaire about: grade level, age of first sexual intercourse, know- ledge concerning prevention and transmission of HIV, desire to marry and to have children with HIV positive person. Ethical aspects: The Ethics Committee of the Centre de Recherche Biomoléculaire Pietro ANNIGONI, CERBA and that of the Centre Médical Saint Camille approved the protocol of the study and all the young people who took part to this research have orally given their informed consent. Data analysis: Statistical analyses were done with Epi-Info version 6 and SPSS version 12. The value of p ≤ 0.05 is considered significant. 3. Results Table 1 shows the classification of frequencies of the 815 individuals of the sample study according to their age and gender. We obtain statistically significant dif- ferences of frequencies in the classification of males and females from 18 to 20 years old (p < 0.001) and from 24 to 26 years old (p = 0.004). There is also a statistically significant difference between the average age of females (22.93 ± 3.04) and of males (23.89 ± 2.92) p < 0.001. Table 2 shows that with regard to illiteracy (p = 0.676), the success in secondary school junior certificate (SSC) and in the leaving certificate (LC) (p = 0.098) and the attendance of university faculties (p = 0.383), there are no statistically significant differences between the two sexes. However, as regards those who hold a primary Table 1. Classification of age groups by gender. Age groups Years Average age Total Number Female Male p FM 18 to 20 19.4 ± 0.8 99 (12.15%) 74 74.75% 25 25.25% <0.001 21 to 23 22.1 ± 0.8 376 (46.13%) 194 51.60% 182 48.40% 0.536 24 to 26 24.8 ± 0.6 252 (30.92%) 103 40.87% 149 59.13% 0.004 27 to 29 27.6 ± 0.7 59 (7.24%) 23 38.98% 36 61.02% 0.099 30 to 32 31.4 ± 0.8 29 (3.56%) 13 44.83% 16 55.17% 0.588 Total 815 407 49.94% 408 50.06% 0.972 Average age 23.59 ± 2.99 22.93 ± 3.04 23.89 ± 2.92 <0.001 X2: 18 20 years. p < 0.001; X2: 20 26 years. p = 0.004. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention among HIV-Serodiscordant Couples in Burkina Faso: 187 Biomedical Issues, Bioethical and Cultural Challenges Table 2. Level of education and knowl e dge about HIV by gender. Level of education Total Female Male p Illiteracy 202/815 (24.79%) 98/202 48.51% 104/202 51.49% 0.676 PSC 187/815 (22.94%) 114/187 60.96% 73/187 39.04% 0.002 SSC-LC 172/815 (21.10%) 75/172 43.60% 97/172 56.40% 0.098 University 254/815 (31.17%) 120/254 47.24% 134/254 52.76% 0.383 Total 815 407 49.94% 408 50.06% 0.972 PSC = Primary School Certificate; SSC-LC = Secondary School junior Certificate-Leaving Certificate. school certificate (PSC), there is a surprising statistically significant difference between the two sexes (p = 0.002). According to Table 3, males state having had their first sexual intercourse (18.94 ± 3.00 years) earlier than females (19.04 ± 2.50). However, there is no statistically significant difference between the two sexes regarding the stated dates of the first sexual intercourses (p = 0.605). Table 4 shows that the group of females has done more HIV test than males, 75.68% versus 62.50 (p < 0.001); that they know more about Preventing Mother-to- Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV than their hus- bands 63.88% versus 56.62% (p = 0.034); that with re- spect to marriage, they would be disposed to get married to an HIV positive 43.24% versus 30.39% (p < 0.001) and would be predisposed to beget a child with the be- loved HIV positive man 33.16% versus 23.39% (p = 0.002). Table 5 presents the knowledge of the modes of HIV transmissions according to the level of study. In this in- vestigation, 47.03% (95/202) of those who are illiterate; 44.77% (77/172) of those who have been to primary/ secondary school (SSC-LC) and 50.00% (127/254) of those who have been to University, did not fully answer the questions, showing thus that they do not clearly know the ways of HIV transmission: sexual transmissions, through parental and vertical transmissions. In addition, 3.46% (7/202) of illiterate people think that mosquito bites transmit HIV. In this table, only 35.34% (288/815) of young people of the survey think that AIDS preven- tion through condoms is the most trustworthy method, whereas some people think that fidelity for couples (32.88%) and abstinence for unmarried individuals (31.78%) are the best ways to avoid HIV/AIDS infection. 4. Discussion The analyses and interpretations of the collected data show: 1) A link between ignorance of HIV transmission, tra- ditional culture, sexual promiscuity and propagation of HIV/AIDS among young people in Burkina Faso: This study shows that the spread of the retroviral infection is caused by the ignorance of the mechanism of HIV trans- mission and juvenile sexual promiscuity. From the sur- vey with the 815 young people (407 girls and 408 boys) aged between 18 and 32 years (average age: 23.59 ± 2.99) in Burkina Faso about HIV/AIDS and procreation, it fol- lows that from now, we know that 30.9% (252/815) of these young people never did their HIV test; 39.8% (324/ 815) never heard about “Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV” (Table 4). However, since 2002, there is a program developed by WHO and the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso for PMTCT [8]. The group of young people who know better of HIV ver- tical transmission is not that of the illiterate (35.64%), nor university graduates (26.38%) or SSC-LC group (20.93%) but the middle educated class: young people who are closer to the popular mass with no more than the primary school certificate (PSC) (46.52%) (Table 5). It is more likely that the girls who are more than 20 years old and do not continue their studies at university have already had their marital experiences and therefore are able to go to health services which address PMTCT. It can be underlined that young people of our study had their first sexual intercourses when they were 18.99 ± 2.76 years old: at 19.04 ± 2.50 for girls against 18.93 ± 3.00 for boys (p = 0.605). In contrast, individuals who have had sex before 17 years old had their first sexual intercourses at 15.55 ± 1.69 years. In this perspective, according to GUIELLA et al., 2006, the sexual life of the Burkinabe starts, for the majority of them, during ado- lescence, because 27% of girls and 22% of boys between 12 and 19 years of age, in their lives, had sexual inter- courses [9,10]. Indeed, during our study, some boys were very proud to say that they had their first intercourses when they were 8 or at 11. According to GUIELLA and collaborators (2006), the proportion of sexually active young people would increase rapidly with age and would Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention among HIV-Serodiscordant Couples in Burkina Faso: 188 Biomedical Issues, Bioethical and Cultural Challenges Table 3. Classification by gender and age at first sexual intercourse. Average age Total Female Male p Female Male X < 17 years 15.55 ± 1.69 211 (25.89%) 102/211 (48.34%) 109/211 (51.66%) 0.628 17 to 22 years 19.36 ± 1.07 448 (59.88%) 254/448 (52.05%) 234/448 (47.95%) 0.365 X > 22 years 23.32 ± 1.51 116 (14.23%) 51/116 (43.97%) 65/116 (56.03%) 0.190 Total 18.99 ± 2.76 815 407/815 (49.94%) 408/815 (50.06%) 0.972 First sexual intercourse year 19.04 ± 2.50 18.94 ± 3.00 0.605 Table 4. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS. 407 Female 408 Male p Answers: Yes or No NO YES* NO YES FY*MY Fear for the test 307 75.43% 100 24.57% 315 77.21% 93 22.79% 0.551 HIV Test 99 24.32% 308 75.68% 153 37.50% 255 62.50% <0.001 Results of HIV Test 357 87.71% 50 12.29% 389 95.34% 19 4.66% <0.001 Know about PMTCT 147 36.12% 260 63.88% 177 43.38% 231 56.62% 0.034 Fiancé with HIV+ 231 56.76% 176 43.24% 284 69.61% 124 30.39% <0.001 HIV Procreation 272 66.83% 135 33.16% 312 76.47% 96 23.53% 0.002 FY = Female yes; MY = Male yes. Table 5. Knowledge of HIV/AIDS prevention and transmission. HIV AFC prevention Mode of HIV transmission Total Abstinence Fidelity Condom Sex Sex-Mtct Sex-Mtct-Pa Mosquitoes Illiteracy 202 65/202 32.18% 97/202 48.02% 40/202 19.80% 35/202 17.33% 88/202 43.56% 72/202 35.64% 7/202 3.46% PSC 187 60/187 32.08% 59/187 31.55% 68/187 36.36% 62/187 33.16% 38/187 20.32% 87/187 46.52% 0/187 0.00% SSC-LC 172 62/172 36.05% 61/172 35.47% 49/172 28.49% 59/172 34.30% 77/172 44.77% 36/172 20.93% 0/172 0.00% University 254 72/254 28.35% 51/254 20.08% 131/254 51.57% 60/254 23.62% 127/254 50.00% 67/254 26.38% 0/254 0.00% Total 815 259/815 31.78% 268/815 32.88% 288/815 35.34% 216/815 26.50% 330/815 40.49% 262/815 32.15% 7/815 0.86% AFC = Abstinence, Fidelity, Condom; PSC = Primary School Certificate; SSC-LC = Secondary School junior Certificate-Leaving Certificate; Mtct = Mother- to-child-transmission; Pa = HIV Parental Transmission. significantly increase with 14 years old youths. The au- thor found in his study that more than 7% of girls of 20 to 24 years old stated having had their first sexual inter- courses before 15 years of age; 62% before 18 years and 83% before 20 years of age[10]. Whereas with boys of the same age group, there are 2.5% who declared having had sexual intercourses before 15 years of age; 32% be- fore 18 years and 57% before 20 years of age [11,12]. Poverty and the social status of adolescent boys, and more so for adolescent girls, can expose them to very Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention among HIV-Serodiscordant Couples in Burkina Faso: 189 Biomedical Issues, Bioethical and Cultural Challenges unequal or even constrained sexual relationships. There- fore, these early and frequent sexual intercourses before marriage could account for the high prevalence of HIV infection in Burkina Faso [13]. AIDS epidemic spreads through the weak bonds of so- cieties. It develops where some backward sexual customs are maintained; where access to information, to preven- tion, economic autonomy and respect of human rights are not guaranteed for all. In Burkina Faso, a lot of tradi- tional practices favored the propagation of HIV. Among the causes of HIV infection, we can mention polygamy, forced marriage, levirate and sororate marriage. Indeed, these three traditions are socio-cultural realities that are still practiced in some ethnic groups in Burkina Faso. One can find, in villages and in big cities, men who get married to many women (two, three, even four or six, according to their social rank and their economic capa- bilities). Therefore, one can find young girls of 17 years old who become the sixth or eighth spouse of a 70 years old rich man or chieftain. According to the traditional law of the Moose, a gerontocratic patrilineal ethnic group in Burkina Faso, it is the head of lineage (head of family, bùud-kasma) or of a segment of lineage, who decides marital unions. Marriage is after all a covenant between two lineages. In this perspective, “marital relationships result from social and political strategies, the making and implementation of which are not opened to the par- ticipation of young men and young women” [14]. Thus, social pressure is often so strong in these socie- ties that it does not leave a place to individual freedom and compels young people to dangerous options, such as getting married, no matter what, despite one’s serious pathology or accepting principles of levirate, taking as wife the spouse of a brother who died from AIDS. Paradoxically, according to Bernard Taverne, the Moose traditional law is fundamentally unequal in its distribution of rights and duties according to gender. It makes a very clear sexual distinction regarding fidelity between husband and wife: the wife has the duty to strictly remain faithful, in comparison to her man who has the right to extramarital sexual intercourses. Besides, the wife has the duty to tolerate extramarital intercourses of her spouse [15]. From this perspective, the duty of women to be faithful is strongly related to the principles of patrilinearity and of “lineage fertilization” which are the foundations of the social structure of the Moose [16]. The child is the property of the lineage of the husband, whereas the wife who is considered within the lineage as a stranger, would be the receiver of a vital principle transmitted through agnatic bond by the ancestors, through the father: the “Sigré” [17]. Thus, female marital fidelity is fundamental in order to control fertilization and the extension of the family (“bùudu”) of the husband. Transgression of the law of marital fidelity by the wife is considered as a serious act which should be punished not only by the husband’s family, but also by his ancestors. 2) Marriage between HIV serodifferent persons and the problematic of HIV transmission: In this research, 36.80% (300/815) of young people, although they are HIV negative would accept to get married to the beloved HIV positive person. There is statistically speaking a significant difference between the two sexes: 43.24% of girls and 30.39% of boys would accept marriage in the case of serodifference (p < 0.001) (Table 4). This obser- vation could be explained by the fact that, as our study shows it, some young people still ignore the modes of HIV infection and think that AIDS is a disease caused by mosquito bites or by sorcerers [18]. 3) Culture and HIV serodifferent partners’ need for a child: In this investigation, 28.34% (231/815) of young people would accept to have a child with a HIV positive spouse: in the case of serodifference, 33.16% of girls against 23.53% of boys would accept to have a child in their couple (p = 0.002) (See Table 4). Despite the fact that girls know more of the principles of Mother-to-Child Transmission (63.88%) than boys (56.62%) (p = 0.034), they would accept more freely, because of cultural rea- sons, to get married, even with a HIV positive spouse, in order to be fulfilled as women through procreation. In- deed, in Burkina Faso, many cultural principles make young girls and young boys get married, no matter what, in order to have children. In some cultures, a single woman, free, without a husband and a child cannot be allowed. Every woman should get married and procreate. A girl without a hus- band is considered to be either a child or an easy woman who is open to any proposal. If she does not find her ful- fillment as a mother, she would be viewed as a sterile woman, with all the contempt that this involves. A boy should get married at a certain age, otherwise he could never be part of the group of adults and deserve having funerals after his death. As a single man, he will be considered to be like a child. These facts would ex- plain in part that there is a strong need to get married no matter what, and then have progenitors. In this perspec- tive, a married man, if he is not sexually active and if he is not able to have a child, cannot avoid having affairs with another woman outside the conjugal family to try his chance. It is difficult to make such a person under- stand the dangers of sexual promiscuity. That man, who experiences a kind of social shame because he did not procreate, finds necessary to try his chance with many women, even with strangers. In these situations, it be- comes very difficult to stop the propagation of AIDS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention among HIV-Serodiscordant Couples in Burkina Faso: 190 Biomedical Issues, Bioethical and Cultural Challenges because of that obsession for procreation, and the blatant ignorance of the modes of transmission of HIV [19]. Everything being considered, generally speaking, we see that the need for a child in serodifferent couples clearly exists today in African societies where the dif- ferent tribes or ethnics have a pronatalist culture. In Africa, more than half of HIV positive persons have access to anti-retroviral medicines. Therefore, patients who are not under ARV treatment, and who see them- selves losing their forces, develop an instinct for procrea- tion and put into contribution their remaining energy to perpetuate their name through the life they will bring about in the child. There is no doubt that there are multiple dangers of infections which threaten HIV serodifferent couples. The fundamental question which follows from that is this: how do we make these individuals who are infected by the virus understand the highly dangerous problematic of the sexual infection and the vertical transmission of HIV? With respect to procreation, certain scholars are for non protected sexual intercourses in HIV serodiscordant couples who have the chance to be under ARV treatment and whose “viremy” cannot be detected. According to doctor VERNAZZA, a specialist on HIV sexual trans- mission, the risk of transmission in that context during non protected sexual intercourse is “very low”, around one out of one million sexual intercourses [20]. For Professor Patrick YENI, at present, the practice of non protected sexual intercourses between serodiscordant couples cannot in any case be recommended in natural conception, because of the risk of contamination that it involves [21]. According to professor Lino CICCONE, objectively, non protected sexual intercourse in a serodiscordant cou- ple, even for the purpose of procreation, is tantamount to an attempt to the life of the healthy spouse. For him, every time a case is sent to court because of HIV trans- mission in a serodiscordant couple, judges always con- demn the infected spouse for a homicide/murder at- tempt21. In the light of these condemnations from courts, CICCONE states that we cannot severely judge these types of behaviour as irresponsible. Thus, it is actually a pity that through a gesture of conjugal love, through a sentiment full of interpersonal love communion, such as the practice of “procreation”, an act of murder is com- mitted which irrevocably leads to the slow physiological degradation of the beloved person, then to his/her death [22] from AIDS. In Sub-Saharan Africa, intra uterine artificial insemi- nation of treated spermatozoids of HIV positive man and that of ICSI (Intra Cytoplasmic Injection of Spermato- zoids) are not yet developed in order to enable HIV sero- discordant couples to procreate. However, in the case in which the man is HIV negative and the woman HIV positive, it would exist self insemination which is easy to do and does not have any risk for the couple. Nonetheless, this technique does not eliminate/prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission. 5. Conclusions This study demonstrated that many young people in Burkina Faso have never been tested for HIV. They have their first sexual intercourse early; they ignore the trans- mission modes and types of HIV prevention. Many young people, due to obsolete traditions, without precau- tion, want to marry the HIV positive person beloved even desiring to have children with him/her. In spite of the fact that HIV serodiscordant couples are aware of the risks related to HIV/AIDS, they remain at- tached to their aspirations to procreate [23]. The extent of this pandemic requires therefore of tradition bearers (re- source persons of ancestral traditions), researchers, health professionals, public health decision-makers, interna- tional organizations and religious leaders, to coordinate their education strategies and their actions. Until now, there is no zero risk in biomedical sciences. For this rea- son, the following questions come to my mind: do we have to give birth to a child even if the child was to be- come orphan, HIV positive and morbid? In developing countries, where AIDS is raging, because less that 50% of the patients have access to antiretroviral medicine: do we stigmatize and discriminate HIV positive people by refusing to celebrate their marriage [24]? Can we advise them to get married but abstain to procreate? Any person of good will and of common sense cannot avoid these multiple vital questions about human relations and mari- tal bonds related to HIV serodiscordant couples or ignore the concerns regarding assisted medical procreation (AMP) for HIV serodifferent couples. There is, indeed, a need for further pluridisciplinary thought to be given to the issue, in order to avoid leading engaged or serodis- cordant couples to make a bad choice which, later, will condemn them or put the lives of other people in danger. In the current context, any HIV positive person should live his/her situation with responsibility by being con- cerned for the good of his/her partner because, for the moment, the discovery of a vaccine or an efficient treat- ment seems implausible in a near future. And through this stressing search for solutions to the pandemic, only wise and just options, from ethical, cultural and bio- medical points of view, can enable the human species to stand together and collectively initiate a new battle to maintain and protect our common humanity, by devel- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention among HIV-Serodiscordant Couples in Burkina Faso: Biomedical Issues, Bioethical and Cultural Challenges Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA 191 oping in us a more responsible behavior. 6. Acknowledgements The Authors are deeply grateful to the staff of Saint Camille laboratory and CERBA. They are grateful to Mr Armand Natewindé SAWADOGO for the translation of the manuscript into English and to Dr André Kaboré and Miss Rebecca COMPAORE for the correction of the manuscript. The authors declare no competing interest. REFERENCES [1] Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, “AIDS Epidemic,” 2009. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/JC1700/Epi/Updat e/2009/en.pdf [2] ONU, “Les Femmes et le VIH/sida: Sensibilisation, Prévention et Emancipation, Journée Internationale de la Femme 2004,” Publication du Département de l’infor- mation de l’ONU-DPI/2343, 2004. http://www.un.org/fr/events/women/iwd/2004/background- erF.pdf [3] Présidence du Faso conseil national de lutte contre le SIDA et les IST, “Revue à Mi-Parcours du Cadre Stratégique de Lutte Contre le SIDA et les IST 2006- 2010,” Document du SP_CNLS, 2008. [4] C. Enah, L. Moneyham, G. Childs and C. A. Gakumo, “Cameroonian Preadolescents’ Perspectives of an HIV Prevention Intervention,” World Journal of AIDS, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2011, pp. 43-49. [5] AVIS, “Problèmes Ethiques Posés par le Désir d’enfant chez les Couples où l’homme est Séropositif et la Femme Séronégative,” N°056 - 10 février, 1998. http://www.ccne-ethique.fr/docs/fr/avis056.pdf [6] A. Ndyakira, “Défis et Espoirs: La Culture Africaine Vulnérabilise les Femmes Séropositives,” http://www.imul.com [7] N. Meda, P. Msellati, P. Van de Perre and R. Salamon “Réduction de la Transmission Mère-Enfant du VIH dans les Pays en Développement: Stratégies d’Intervention Disponibles, Obstacles à Leur Mise en œuvre et Per- spectives,” Cahiers Santé, Vol. 7, No. 2, 1997, pp. 115- 125. [8] OMS, “Prévention de la Transmission Mère-Enfant du VIH/Sida au Burkina Faso,” ONUSIDA, Département du VIH/SIDA, http://www.who.int/hiv/en [9] G. Guiella and N. J. Madise, “HIV/AIDS and Sexual- Risk Behaviors among Adolescents: Factors Influencing the Use of Condoms in Burkina Faso,” African Journal of Reproductive Health, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2007, pp.182-196. [10] G. Guiella and V. Woog, “Santé Sexuelle et de la Reproduction des Adolescents au Burkina Faso: Résultats de l’Enquête Nationale sur les Adolescents du Burkina Faso 2004, Occasional Report,” Guttmacher Institute, New York, 2006, p. 152. [11] A. Gal-Régniez, G. Guiella, C. Ouédraogo, V. Woog, D. Bassonon, L. Darabi, et al., “Protéger la Prochaine Génération au Burkina Faso,” Guttmacher Institute, New York, 2007. [12] World Health Organization, “Enquête Démographique et de Santé, Burkina Faso,” ORC Macro, Measure DHS Statcompiler, 2003. www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/countries/bfa.pdf [13] J. Simpore, V. Pietra, S. Pignatelli, D. Karou, W. M. C. Nadembega, D. Il-boudo, et al., “Effective Program against Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV at Saint Camille Medical Centre in Burkina Faso,” Journal of Medical Vi- rology, Vol. 79, No. 7, 2007, pp. 873-879. doi:10.1002/jmv.20913 [14] J. Capron and J. M. Kohler, “Migration de Travail et Pratique Matrimoniale; Introduction, Exploitation de l’ enquête par Sondage,” Document de travail, Ouaga- dougou, ORSTOM, 1975, p. 63. [15] B. Taverne, “Valeurs Morales et Messages de Prévention: La ‘Fidélité’ Contre le sida au Burkina Faso,” 1999. http://www.codesria.org/Links/Publications/aids/taverne. pdf. [16] D. Bonnet, “Corps Biologique, Corps Social. Pro- création et Maladies de l’enfant en Pays Mossi, Burkina Faso,” ORSTOM, Paris, 1988, p.138. [17] J. Simpore, “Personalism in the Cultural Area of the Africa,” Medicina e morale, Vol. 54, No. 2, 2004, pp. 353-360. [18] R. Mburano, “Facteurs Contextuels de la Transmission Sexuelle du Sida en Afrique Subsaharienne: Une Syn- thèse,” 1999. www.codesria.org/Links/Publications/aids/rwenge.pdf [19] J. Simpore, “Enjeux Culturels, Biomédicaux et Ethiques de Procréation Chez les Couples VIH Sérodiscordants,” Acçao Medica, Vol. 70, No. 2, 2006, pp. 89-103. http://csgois.web.interacesso.pt/revista/setembro2006.pdf [20] P. L. Vernazza, L. Hollander, A. E. Semprini, D. J. And- erson and A. Duerr, “HIV-Discordant Couples and Par- enthood: How Are We Dealing with the Risk of Trans- mission?” AIDS, Vol. 20, No. 4, 2006, pp. 635-636. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000210625.06202.c2 [21] P. Yeni, “Prise en Charge Médicale des Personnes In- fectées par le VIH,” Recommandations du groupe d’ex- perts, 2006. http://www.sante.gouv.fr/ [22] L. Ciccone, “Bioetica, Storia, Principi, Questioni,” Ares, Milano, 2003, pp. 1-383. [23] M. K. McClellan, R. patel, G. Kadzirange, T. Chipatod, and D. Katzenstein, “Fertility Desires and Condom Use among HIV-Positive Women at an Antiretroviral Roll- Out Program in Zimbabwe,” African Journal of Repro- ductive Health, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2010, pp.27-35. [24] E. Monjok, A. Smesny and E. J. Essien, “HIV/AIDS- Related Stigma and Discrimination In Nigeria: Review of Research Studies and Future Directions for Prevention Strategies,” African Journal of Reproductive Health, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2009, pp. 21-35.

|