World Journal of AIDS, 2011, 1, 198-207 doi:10.4236/wja.2011.14029 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/wja) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea Marie Lucy Aska, Jiraporn Chompikul*, Boonyong Keiwkarnka ASEAN Institute for Health Development, Mahidol University, Salaya, Thailand. E-mail: *adjcp@mahidol.ac.th Received July 22nd, 2011; revised September 29th, 2011; accepted October 11th, 2011. ABSTRACT The objective of this study was to identify determinants of fertility d esires in HIV positive women living in the Western Highlands Province, Papua New Guinea, a male-dominated, patrimonial society. A cross-sectional study was con- ducted to collect data in February, 2010. Two hundred and ninety one HIV-infected women participated in personal interviews using a structured questionnaire. Sixty-six percent of the respondents were in polygamous relationships. Thirty-four percent of the participants desired a child in the future. Chi-square tests revealed that variables associated with desire for a child were age, marital status, number of children, current co-habitation with a partner, duration of time with a partner, receipt of the bride price, domestic physical violence, sexual activity in the previous th ree months, partner’s desire for a child, and current contraceptive use. Using multiple logistic regression, a partner’s positive de- sire for a child was th e strongest predictor, with an odds ratio of 13.04 (95% CI = 5.68 - 29.91). Fertility desires were largely influenced by dominant culturally sensitive issues and the family-oriented culture. The integration of effective counseling and reproductive health care service into HIV clinics is recomm ended. Holistic , culturally-relevant and fam- ily-oriented reproductive health counseling should provide more positive outcomes for both HIV-infected women and their children. Keywords: Fertility Desires, HIV Positive Women, Papua New Guinea, Reproducti v e H ea lth, Patrimonial Society 1. Introduction As HIV treatment has become more widely available and improved the life expectancy and overall health of HIV positive men and women, there is an increasing need to understand the reproductive desires and sexual behavior of women living with HIV/AIDS. Women of reproduc- tive age constitute one of the fastest growing and largest groups infected with HIV/AIDS according to UNAIDS [1,2]. Of the 14,000 infections per day worldwide, 1600 are through vertical transmission, that is, from mother to child transmission of HIV [3]. In the past, pregnancy has been discouraged among women living with HIV/AIDS (WLWHA) because of ethical and clinical concerns about vertical transmission and maternal health [4]. However, more recently, as HIV treatment has improved and be- come more widely available, there is interest in the re- productive desires and sexual behavior of WLWHA. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is one reason people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in Nigeria have reconsidered or resumed sexual relationships and childbearing [5]. Vertical transmission has been reduced by the introduc- tion of Zidovudine proph ylaxis [6,7 ] an d through electiv e caesarean section [8]. Though not available in Papua New Guinea (PNG), advanced western medical technol- ogy, including assisted techniques such as artificial in- semination and in vitro fertilization (IVF), have also re- duced the risk of horizontal transmission [9,10]. More- over, mentors like Amnesty International and the Inter- national Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS have promoted human rights and fundamental freedoms, especially in the areas of sexual and reproductive rights, addressing the reproductive health care needs of WLWHA [11,12]. These medical advances and ART are not widely available in all provinces in PNG, and are therefore inef- fective in reducing the childbearing risks faced by WLWHA in this region. Because of the strong family oriented cu lture and the cultural expectations fo r women,  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands 199 Province of Papua New Guinea this makes it increasingly important to address the issue of reproductive counseling and management for HIV individuals during their reproductive years. It is also im- portant to determine factors related to fertility desires. Psychosocial, cultural and medical factors greatly influ- ence the reproductive decisions of WLWHA [13]. How- ever, no such study has been carried out in PNG which may have unique cultural and social traditions, not often encountered in other countries. In the United States of America (USA), HIV infected women are put in a difficult position when it comes to reproductive decisions [14]. WLWHA struggle to decide between their personal desires and socio-cultural expec- tations concerning fertility, wh ile simultaneo usly fighting psychological condemnation and stigmatization regard- ing HIV infection, pregnancy and fear of vertical trans- mission [14,15]. Despite this dilemma, studies have shown that WLWHA still express their desires to bear children even after learning their status [15-21]. In Nige- ria, wh ere marri age and famil y are impo rtant, res earch in 2007 indicated that PLWHA whose health has been re- stored by ART have strong desires for marriage and children. This poses a very real and practical danger as public health messages and infection preventative meas- ures clash with social expectations [5]. PNG is known as one of the world’s most culturally diverse countries. Eighty-seven percent of the population lives in rural areas with little access to basic health care services due to the difficult terrain. PNG is a male domi- nated society with strong cultural practices [22]. Gender inequities, sexual violence and social acceptance of vio- lence against women in PNG have been identified as major factors contributing to the rapid spread of HIV/ AIDS in the country [23]. PNG has one of the highest HIV prevalence of 1.28% in 2008 in the Pacific region with heterosexual sexual intercourse being the most common mode of transmis- sion [24-25]. Infection in females is highest in younger women aged 19 to 29, at the peak of their reproductive lives [25]. Reproductive decisions in PNG are further complicated by social issues and the traditional practices of paying a bride price and polygamous marriages [26]. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) and prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) services are currently bein g implemented across the country, now in their fifth year [27]. It has been observed that HIV positive women are becoming pregnant. Therefore, there is ample need for this study in the country; it may establish a baseline for preventio n of mother-to- child HIV infection. As it is be- coming increasingly important to address the issue of reproductive counseling and management for HIV indi- viduals during their reproductive years, it is also impor- tant to understand the issues and factors related to their fertility desire. This study, therefore, identifies factors associated with the fertility desires of WLWHA in the Western Highlands Province (WHP) of PNG as they face the challenges of living with HIV infection in a strongly male dominated culture. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Study Design and Study Sites This was a cross-sectional descriptive study conducted in February 2010. The study took place in the WHP of PNG, where HI V p revalence was high [25]. 2.2. Target Population The target population was women aged 18 to 45 years old who had been confirmed as HIV positive using blood tests at the Tininga or Rebiamul Clinics at least three months prior to the interview, and who were residing in the WHP. Sexual and marriage traditions are similar throughout the Highlands region [26]. Women were ex- cluded from the study if they were single, had HIV stage 3 or 4 at the time of interview, had a history of or current psychiatric problems, or had a history of tubal ligation or hysterectomy. The exclusion of women at HIV stages 3 and 4 from the study was due to medical concerns that such women would be too sick to be interviewed and also because, at those stages, they could be distracted and be unable to complete the interview completely. Women younger than 18 years were excluded because of con- cerns about guardians’ permission and disclosure of their HIV status. 2.3. Data Collection Methods and Tools Participation was voluntary; participants were recruited during follow-up visits to the clinics on their appoint- ment dates, and after the purpose of the study had been made known in the clinics. Those who volunteered were given further information in a private room in one of the clinics, where a consent form was signed and interviews were conducted by a trained and experienced interviewer. Interviews lasted 15 to 20 minutes. Because the lead au- thor was also the principal researcher and interviewer and had had extensive experience working as a medical practitioner in the two clinics for over 2 years, a strong degree of mutual trust and respect had been developed with most of the participants. There was, in fact, no re- luctance or prevarication on their part in answering the questions posed. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data. It was designed to elicit information about participants’ demographical background, relationship status, psycho- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands 200 Province of Papua New Guinea social factors, medical factors, and fertility desires. Psy- chosocial factors included experience of domestic vio- lence, sexual activity in the previous three months, sex- ual assault in the relationship, payment of the br ide price, and disclosure of status. Medical factors included ART status and duration of treatment, time since HIV diagno- sis, clinical stage for HIV at the time of diagnosis, knowledge regarding prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT), contraceptive use, and accessi- bility and efficacy of the reproductive services provided in the clinics. Fertility desires is defined as a psychological state in which someone has the personal motivation to have a child. Such motivatio n represents the first step towards a decision to act, typically followed by an intention to do so [28-29]. One question in the structured interview in particular asked about fertility desires: “What best de- scribes your thinking about having a child in the near future?”. Respondents could answer: 1) “I want a child in the near future”; 2) “I am unsure or undecided now”; 3) “I have decided that I do not want to have a child in the future”. Additional open-ended questions were asked about the reasons for their particular fertility desire choice, and the results were grouped into main themes, and used to sup port the findings obtained from the stat is- tical analysis. Five questions were asked about PMTCT. For a possi- ble maximum score of five; correct answers scored 1 while incorrect or unsure answers scored 0. Using Bl- oom’s criteria, a total score of 80% or more indicated good knowledge; 60% - 80% indicated moderate knowl- edge; and a score of less than 60% indicated poor knowledge. Before data collection, the questionnaire was pretested on a group of 30 HIV positive women aged 18 to 45 years from a HIV clinic in the WHP of PNG. The reliability of the questions regarding PMTCT, using the Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20), was 0.5. 2.4. Ethical Aspects The study proposal was approved by the Mahidol Uni- versity Institutional Review Board and also by the PNG National AIDS Council Secretariat Research Advisory Committee. All participants were informed of the objec- tives of the study and of their right to choose to partici- pate or not and of th eir righ t to leav e th e study at anyti me they wished. The purpose of the study was explained to all participants before informed written consents were obtained. Women who could not read or write had the consent read and explained to them; those volunteering to participate made a mark on the consent form with their right index fingers as a sign of their willingness to par- ticipate. Data were kept strictly confidential. 2.5. Data Analysis Data were analyzed using Minitab; results have been analyzed with descriptive statistics and inferential statis- tics, using Chi-square tests and multiple logistic regres- sion. The confidence interval was set at 95% and the p-value was <0.05 for a significant association. Re- sponses to the open-ended questions indicated why par- ticipants had a positiv e or negative desire for a ch ild. The reasons were then grouped into main theme areas; some representative quotes are presented to illustrate their re- sponses. 3. Results A total of 296 HIV positive women were interviewed. Five did not meet the criteria (two were single, two had a history of tubal ligation and one was not from the High- lands provinces of interest in this study). Therefore, the final sample size used for analysis was 291. 3.1. Reasons for and against Fertility Desires Out of the 291 participants, 34% desired a child, 59% had no desire for a child and 7% were unsure or unde- cided about whether they wanted a child in the near fu- ture or not, as shown in Table 1. The participants in this study offered a co mplex range of reasons for and against having a child. The most common reasons given for not having a child were related to medical concerns. Some respondents feared infecting a new partner (31%); some feared of infecting the child (23%) and some were con- cerned about the det eri o rat i o n of their o wn heal t h (2 5%). Reasons for a positive desire for a child seemed to be more socially and culturally oriented. The most common reasons for wanting a child were that the participants wanted someone to replace them (35%), followed by their desir e for protection and suppor t in old age (22%). 3.2. Socio-Demographic, Medical and Psychosocial Characteristics Table 2 shows most participants were aged 26 - 35 years, were in polygamous marriages, and were subsistence farmers with very low incomes. Forty percent were childless. Table 3 shows most patients had AIDS when they were first diagnosed, had received ART for over 18 months and had a fair degree of knowledge about PMTCT. Table 4 shows 45% of patients had been the subject of bride price payments in their marriages; 54% had experienced domestic physical assault; 52% had ex- perienced sexual violence in their marriages; and 42% were sexually active. 3.3. Factors Associated with Fertility Desires Chi-squ are tests indic ated age, numb er of children, mari- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA 201 Table 1. Fertility desires and reasons for fertility desires. Number Percent Fertility Desire Desire for a child No desire for a child Unsure Concern or fears about fertility desires (more than one answer possible) Fear of infecting a new partner Fear of my health deteriorating during and after childbirth My family is complete Fear of having an infected child Economic burden o f raising a fami ly Partner dead or absent (I’m alone) Stigmatization by the community Reasons for positive fertility desires (more than one answer possible) I need a replacement in the future For protection, support and to look after me I have no children I want a child I have only one child I want another Partner wants a child I want a boy To strengthen marriage Community pressure I want surplus land Believes ART/PMTCT allows for an uninfected baby Still young Replacing baby who died 99 173 19 192c 59 48 46 44 37 18 14 99d 35 22 20 18 16 12 8 6 5 4 4 3 34.02 59.45 6.53 30.73 25.00 23.96 22.91 19.27 9.38 7.29 35.35 22.22 20.20 18.18 16.16 12.12 8.08 6.06 5.05 4.04 4.04 3.03 cNumber of r espondents who were unsure or desired not to have a child; dNumber of respondents who desired to have a child. tal status, current co-habitation with a partner, period of time living with a partner, bride price payment, physical assault, sexual activity in the previous three months, partner’s desire for a child, and use of contraception each had a significant association with fertility desires (Table 5). Women aged 18 to 25 years were six times more likely to desire a child than those women over the age of 36. Women who had had no children were four times more likely to desire a child than those who had more than two child ren alread y. Cov ariates (educatio n , religion , position in a polygamous marriage, occupation, history of child death due to HIV, having a female child, HIV stage, ART status, duration on ART, PMTCT knowledge, and accessibility and efficacy of reproductive services) which had no significant association are not included in Table 5. Having a male child in the family and disclo- sure of HIV status to a partner were found to be strongly but not significantly associated with fertility desires. The results of multiple logistic regression (Table 5) revealed that predictors for desires for a child were: younger age, having no children, and having a partner who desired a child. A partner’s positive desire for a child, as perceived by their wives, was the strongest pre- dictor, with an odds ratio of 13.04 (95% CI = 5.68 - 29.91). 4. Discussion and Conclusions This study found that 34% of HIV positive women ex- pressed a desire for a child in the future. Women who desired a child were younger, married, in a sexually ac- tive relationship with no children, and had partners who desired a child. Most factors associated with fertility desires in this study are related to the influence of a patrimonial society, culture, gender inequ ities and psycho so cial issues of such variables as bride price and domestic violence, spousal desires, and number of children. Traditional PNG High- lands society places a very strong belief in male domin- ion over the land and family. The man is the leader of th e family. Family decisions are final when the husband speaks. Women hold an inferior position. It was, there- fore, not surprising to find that the strongest pred ictor for  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands 202 Province of Papua New Guinea Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants. Characteristics Number (%) Characteristics Number (%) Age Group 18 - 25 years old 26 - 35 years old 36 - 45 years old Mean = 29.61, SD = 5.43 Min = 18 , Max = 45 Origin (Province) Western Highlands Southern Highlands Enga Simbu Education No education Primary Secondary University/Tertiary collage Occupation Subsistence farmer Laborer Government employee Private company employee Small business operator Housewife Average monthly income (PNG Kina) Less than K100 K100 - K500 K500 and over Mean = K191 SD = 319, Min = K10, Max = K3000 78 (26.80) 169 (51.08) 44 (15.12) 198 (68.04) 41 (14.09) 40 (13.75) 12 (4.12) 113 (38.38) 114 (39.18) 56 (19.75) 8 (2.75) 189 (64.95) 8 (2.75) 8 (2.75) 16 (5.05) 35 (11.34) 37 (12.71) 203 (69.76) 69 (23.71) 19 (6.53) Religion Roman Catholic Lutheran Baptist Seventh Day Adventist Pentecostal Other small denominations Marital status Married/Cohabiting Separated/divorced Widowed Position in polygamous marriage 1st & only wife 1st wife with subsequent wives 2nd wife 3rd or more wif e Have a male chi l d Nil One or more Have a female child Nil One or more History of child death due to HIV/AIDS Yes No Currently living with a partner Yes No Duration of time with current partner Less than 1 year 1 - 5 years More than 5 years 75 (25.77) 43 (14.78) 8 (2.75) 42 (14.43) 106 (36.43) 17 (5.84) 156 (53.16) 87 (29.90) 48 (16.49) 99 (34.02) 90 (30.93) 63 (21.65) 39 (13.40) 176a 49 (27.84) 127 (72.16) 226a# 60 (34.09) 166 (65.91) 65 (22.34) 226 (77.66) 166 (57.04) 125 (42.96) 166b 14 (8.43) 61 (36.75) 91 (54.82) aTotal number of respondents who currently have biological son; a# Total number of respondents who currently have biological daughter; b Total number of respondents currently living with a partner. fertility desires was the male partners’ desires for a child. Bride price payment is a psychosocial issue. A woman whose husband and family have paid a bride price to her family feels obligated to bear a child. Bride price pay- ment by a male spouse and his clan generates reciprocal expectations and demands to bear a child to contribute to the male’s kin and community. Child bearing and nur- turing largely defines a woman’s social identity and status in PNG. Being childless is a disappointment to and a disgrace for a couple. Children, especially male chil- dren, are a valuable asset in terms of security, strong tribal alliances and support [30]. Studies from Brazil [18], South Africa [21], Uganda [31], and the USA [19] also show that the number of children is associated with the desire for a child. Age is also a predictor for fertility desires. As the HIV epidemic has spread in PNG, the highest rate of infection has occurred in women aged 15 to 29 [24,25] and coin- cides with the beginning and peak of their reproductive lives. It is, therefore, critical to establish reproductive service programs in HIV clinics to assist WLWHA in the prevention of unwanted pregnancies and also to ensure that desired conception and birth take place as safely as possible. The need for reproductive counseling is all the more urgent in light of the study finding that about 80% of respondents in this study had never asked questions about or discussed their reproductiv e health issues with a health worker in the clinics. Male child preference is still evident in the Highlands of PNG, as it is in the African [31] and Asia regions Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands 203 Province of Papua New Guinea Table 3. Medical characteristic s of study participants. Characteristics Number (%) Characteristics Number (%) HIV Clinical Stage at the first diagnosis 1 2 3 4 Time since HIV dia gnosis <6 months 6 - 18 months >18 months ART status Yes No Duration on ART <6 months 6 - 18 months >18 months Knowledge regarding PMTCT High Moderate Low Mean = 3.60, SD = 0.96, Max = 5, Min = 0 15 (5.15) 59 (20.27) 164 (56.36) 53 (18.21) 63 (21.65) 79 (27.15) 149 (51.20) 240 (82.47) 57 (17.53) 44 (18.33) 72 (30.00) 127 (51.67) 35 (12.03) 216 (74.23) 40 (13.73) Accessibility and efficacy of reproductive service Ever asked questions about reproductive intention, PMCTC or family planning to health worker Yes No Health workers’ attitude and role towards reproductive intentions, PMTCT and family planning services Do not talk about this at all Provide very little information They seem to ignore or discourage the topic They are helpful Current use of contraception Yes No 59 (20.27) 232 (79.73) 107 (36.77) 105 (36.08) 22 (7.56) 57 (19.59) 85 (29.21) 206 (70.79) Table 4. Psychosocial characteristics of study participants. Characteristics Number (%) Characteristics Number (%) Bride price payments in marriage Yes No Physical assaults/violence Yes No Sexual assault Yes No Sexually active in last 3 months Yes No 131 (45.02) 160 (54.98) 156 (53.66) 135 (46.39) 152 (52.23) 139 (47.77) 123 (42.27) 168 (57.73) Disclosure of HIV status a) To Partner Yes No b) To Public community Yes No Partner’s desire for a child Yes Unsure No 238 (81.79) 53 (18.21) 89 (30.58) 202 (69.49) 79 (27.15) 173 (59.45) 39 (13.40) [32,33]. A male heir in this patrimonial society is valu ed, especially because of customary land rights. Sons and brothers form strong alliances [30]. This is true espe- cially in parts of the Highland s of PNG where tribal con- flicts and ethnic clashes are frequent [34]. Although there was a strong but not significant association in this study, preference for a male child was a common reason for wanting a child. There was no significant association between medical factors and fertility desires, except for use of contracep- tion. Respondents who used contraception tended to be more likely to desire a child, although a similar study in Canada found no such association [20]. In the present study, women who used contraception were more likely to desire a child than those who did not. There may well be a simple explanation for this apparent paradox. The use of contraception did not necessarily indicate a desire not to have a child. Rather, the use of contraception was intended to control the timing of conception and birth. Those women who had not experienced domestic physical violence/assaults were more likely to desire a child than those who experienced domestic violence in their relationships (OR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.01 - 2.68), although this was not a predctor after multiple logistic i Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands 204 Province of Papua New Guinea Table 5. Relationships between independent variables and fertility desires. Characteristics Total n = 291 Desire a child (%) Unadjusted OR (95% CI) P-value Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) P-value Age group 36 - 45 26 - 35 18 - 25 Number of children 2 & more 1 0 Having a male c h ilde Yes No Marital Status f Married/cohabiting Separated/divorced Widowed Currently living with partner Yes No Duration of time with partnerg >5 years 1 - 5 years <1 years Bride price payment in marriage No Yes Physical violence in marriage Yes No Sexually active in last 3 months Yes No Disclosure of HIV status to partner Yes No Partner’s desire for a child Not sure/No Yes Use of contraception No Yes 44 169 78 101 75 115 n = 176a 127 49 156 87 48 166 125 n = 166b 91 61 14 160 131 156 135 123 168 238 53 212 79 206 85 11.36 36.09 42.31 17.82 34.67 47.83 21.26 34.69 43.59 31.03 8.33 45.78 18.40 36.16 62.30 42.86 26.88 42.75 28.85 40.00 49.59 22.62 36.55 22.64 17.45 78.48 32.37 56.47 1 4.41 (1.65 - 11.77) 5.72 (2.03 - 16.08) 1 2.45 (1.22 - 4.91) 4.23 (2.26 - 7.92) 1 1.97 (0.95 - 4.07) 1 0.58 (0.33 - 1.01) 0.12 (0.04 - 0.34) 1 0.27 (0.15 - 0.46) 1 3.05 (1.55 - 5.97) 1.38 (0.44 - 4.34) 1 2.03 (1.24 - 3.32) 1 1.64 (1.01 - 2.68) 1 0.30 (0.18 - 0.49) 1 0.51 (0.25 - 1.02) 1 17.25(9.07 - 32.82) 1 3.94 (2.31 - 6.67) 0.003 0.001 0.012 <0.001 0.068 0.056 <0.001 <0.001 0.001 0.518 0.005 0.046 <0.001 0.056 <0.001 <0.001 1 4.37 (1.20 - 15.97) 5.51 (1.36 - 22.38) 1 2.04 (0.81 - 5.11) 3.63 (1.48 - 8.90) 1 0.76 (0.27 - 2.13) 1 1.09 (0.54 - 2.20) 1 1.71 (0.89 - 3.30) 1 1.11 (0.44 - 2.80) 1 1.37 (0.55 - 3.42) 1 13.04(5.68 - 29.91) 1 0.43 (0.18 - 1.02) 0.026 0.017 0.130 0.005 0.601 0.801 0.107 0.825 0.494 <0.001 0.056 atotal number of respondents who currently have biological son; btotal number of respondents currently living with a partner; eHaving a mal e chi ld was no t us ed in multiple logistic regression as n was only 176; fMarital status was not included in multiple logistic regression as it was a cofounder of currently living with partner; gDuration of time with partner was not used in multiple logistic regression as n was less than 291, even though significant. regression analysis. The women who desired children were also more likely to live in stable, happy relation- ships with their partners. However, over 50% of the par- ticipants experienced domestic violence and other studies have also shown that the majority of PNG women report having been beaten by their boyfriends or husbands be- cause of sexual jealously or for refusal of sex on demand. These were the most common reasons given for violence in an established relationship [35-36]. In explaining her reason for wanting a child, one participant in this study said, “I want a child because my husband demands it and he beats me up”. Physical domestic violence in WLWHA, therefore, also needs to be investigated, and appropriate counseling and reproductive options made available to Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands 205 Province of Papua New Guinea the victims of such behavior. Over 50% of the respondents had been sexually as- saulted in their relationships. Sexual assault is an issu e of great concern in PNG. Of the 152 respondents who had experienced sexual assaults, about 30% were using con- traception, meaning that about 70% were not, and that sexual assault may contribute to unwanted pregnancies and an increased chance of pediatric HIV transmission. This, in turn, further emphasizes the need for family planning counseling and contraception to be more easily accessible. Almost half of the women interviewed who had been sexually active in the previous three months did not de- sire a child, and of those, 56% were not on any form of contraception. This constitutes risky sexual behavior among HIV positive women and increases the risk of transmitting an ART resistant virus to their sexual part- ners if ART resistance had been developed by one part- ner through poor ART adherence. A Ugandan study by Maier et al found no significant association between be- ing sexually active and fertility desires [37]. A partner’s positive desire for a child was very strongly associated with positive fertility desires. This is consistent with studies from Northeast Brazil [18,38]. Despite rapid social changes and westernization, PNG still maintains its patriarchal traditions and gender based power in relationships [23]. Masculine dominance is pronounced and very evident in PNG communities. The male is the family leader and the final decision maker, and in most communities it has become the norm to physically assault the female spouse [23]. Female inferi- ority and lack of power are also evident at the national level, where currently there is only one female in the national House of Representatives out of a total of 109 representatives. In Uganda, the most common reasons for women wanting a child included the desire for a successor, not already having a boy, and having no children at all [31]. The similarity with this present study may lie in the socio-cultural backgrounds of Uganda and PNG. Both are male dominated societies; both accord lower status to women; and both are polygamous. The desire to ensure family continuity in the future, to have offspring of their own to perpetuate their name and lineage after they die, and to be supported in old age are all reasons for the importance of a child in a patrimonial society. The practice of polygamy still remains a threat to married women and a child may strengthen and seal a marriage. WLWHA may be willing to sacrifice the health of an unborn child and their own health to save their re- lationships. Moreover, reasons such as community pres- sure and surplus lan d area show how culture and tradition influence fertility desires. In summary, the findings of this research relate mainly to the culture, customs and psychosocial status of women in PNG. Nevertheless, they demonstrate that medical professionals practicing in this environment need to dis- cuss and counsel WLWHA, and their partners, about contraception and reproductive health more holistically. They need to take into account that a patient is a social being and not just an indiv idual with medical needs. It is also extremely important to integrate reproductive health and family planning services into the programs and rou- tines of HIV clinics. Spousal expectations, community pressure, domestic violence, sexual assault and bride price payments all signify the influence of male domi- nance. There still needs to be more advocacy at the community level for the empowerment of women. Fur- ther research into sexual behavior and contraceptive use involving WLWHA and their spouses also needs to be conducted, with the ultimate goal of reducing the inci- dence of HIV infection and helping WLWHA and their partners live happier and longer lives. The most interesting finding is that PMTCT knowl- edge did not correlate with desire for a child: women independently desire a child regardless of whether they know how to avoid vertical transmission or not. PNG’s PMTCT services are only in the second year of operation in the WHP and do not yet exist at all in oth er provinces of PNG. More extensive advocacy, awareness and pro- motion of PMTCT services, therefore, are particularly urgent. Awareness of the possibilities and choices of- fered through these services may be expected to contrib- ute to the empowerment of WLWHA in particular. 5. Acknowledgements We are greatly indebted to the women living with HIV/AIDS in the Western Highlands Province of PNG for participating in this study. We thank Mr. Peregrine W.F. Whalley for his comments and suggestions about language and style. We also acknowledge WHO and the PNG National Aids Counsel Secretariat for partially funding the study. REFERENCES [1] UNAIDS, “2008 Report on Global AIDS Epidemic (Full Report),” 2009. http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/Gl obal Report/2008/2008Global report.asp [2] UNAIDS, “AIDS and Gender Fact Shee,” 2008. http://womenandaids.unaids.org/publications_facts [3] WHO, “World Health Organization Constitution,” 2010. http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands 206 Province of Papua New Guinea [4] Centre of Disease Control and Prevention, “Current Trends Recommendation for Assisting in the Prevention of Perinatal Transmission of Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type III Lymphadenopathy-Associated Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 34, 1985, pp. 721-726. [5] D. J. Smith and B. C. Mbakwem, “Life Projects and Therapeutic Itineraries: Marriage, Fertility, and Antiret- roviral Therapy in Nigeria,” AIDS, Vol. 21, Suppl. 5, 2007, pp. S37-S41. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000298101.56614.af [6] Centre of Disease Control and Prevention, “Recommen- dations of the US Public Health Service Task Force on the Use of Zidovudine to Reduce Perinatal Transmission of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 43, 1994, pp. 235-238. [7] L. Mandelbrot, L. J. Chenadec, A. Berrebi, et al., “Peri- natal HIV-1 Transmission: Interaction between Zido- vudine Prophylaxis and Mode of Delivery in the French Prenatal Cohort,” Journal of the American Medical Asso- ciation, Vol. 280, No. 1, 1998, pp. 55-60. doi:10.1001/jama.280.1.55 [8] C. Kind, C. Rudin and C. A. Siegrist, “Prevention of Ver- tical HIV Transmission: Additive Protection Effect of Elective Caesarean Section and Zidovudine Prophylaxis,” AIDS, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1998, pp. 205-210. doi:10.1097/00002030-199802000-00011 [9] S. Marina, F. Marina, R. Alcolea, et al., “Human Immu- nodeficiency Virus Type 1—Serodiscordant Couples Can Bear Healthy Children after Undergoing Intrauterine In- semination,” Fertil Steril, Vol. 70, No. 1, 1998, pp. 35-39. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00102-2 [10] A. E. Semprini, P. Levi-Setti, P. Bozzo, et al. , “Insemina- tion of HIV Negative Women with Processed Semen of HIV Partners,” Lancet, Vol. 340, No. 8831, 1992, pp. 1317-1319. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)92495-2 [11] Amnesty International Public Statement, “International Women’s Day: Failure to Respect the Rights of Women Deprives Us All,” 2010. http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/ACT77/004/2009/ [12] ICW, “International Community of Women Living with HIV/AIDS Goals,” 2010. http://www.icw.org/ [13] A. Kline, J. Strickler and J. Kempf, “Factors Associated with Pregnancy and Pregnancy Resolution in HIV Sero- positive Women,” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 40, No. 11, 1995, pp. 1539-1547. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)00280-7 [14] D. Ingram, S. Hutchinson, “Double Binds and the Re- productive and Mothering Experiences of HIV-Positive Women,” Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2000, pp. 117-132. doi:10.1177/104973200129118282 [15] M. S. Craft, R. O. Delaney, D. T. Bautista, et al., “Preg- nancy Decisions among Women with HIV,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 11, No. 6, 2007, pp. 927-935. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9219-6 [16] B. Nattabi, J. Li, C. S. Thompson, et al., “A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing Fertility Desires and Inten- tions among People Living with HIV/AIDS: Implications for Policy and Service Delivery,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2000, pp. 949-968. [17] H. Aka-Dago-Akribi, A. Desgrees Du Lou, P. Msellati, et al., “Issues Surr ounding Reprod uctive Choices for Women Living with HIV in Abidjan, Coted’Ivoire,” Reproductive Health Matters, Vol. 7, No. 13, 1999, pp. 20-29. [18] A. A. Nobrega, A. F. Oliveira, T. M. Galvoa, et al., “De- sire for a Child among Women Living with HIV/AIDS in Northeast Brazil,” AIDS Patient Care and STDs, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2007, pp. 261-267. doi:10.1089/apc.2006.0116 [19] L. J. Chen, K. A. Phillips, D. E. Kanouse, et al., “Fertility and Intentions of HIV-Positive Men and Women,” Fam- ily Planning Perspectives, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2001, pp. 144- 152. [20] M. R. Loutfy, T. A. Hart, S. S. Mohammed, et al., “Fer- tility Desires and Intentions of HIV Positive Women of Reproductive Age in Ontarrio, Canada: A Cross-Sectional Study,” PLos One, Vol. 4, No. 12, 2009, pp. 1-10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007925 [21] L. Myer, C. Morroni and K. Rebe, “Prevalence and De- terminants of Fertility Intentions of HIV-Infected Women and Men Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy in South Af- rica,” AIDS Patient Care and STDs, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2007, pp. 278-285. doi:10.1089/apc.2006.0108 [22] World Health Organization, “Papua New Guinea Country Profile,” 2010. http://www.who.int/countries/png/en/ [23] Amnesty International, “Violence against Women in Papua New Guinea,” September 2006. http://asiapacific.amnesty.org/library/ [24] UNAIDS, “PNG UNGASS Country Report,” 2010. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/papua_new_guine a_2008_country_progress _report_en.pdf [25] National AIDS Council Secretariat and National Depart- ment of Health (NACS and NDOH), “The 2007 Estima- tion Report on the HIV Epidemic in Papua New Guinea,” Port Moresby, 2007. [26] C. Jerkins, “HIV/AIDS; Culture and Sexuality in Papua New Guinea. Executive Summary,” 2010. http://www.adb.org/Documents/Books/Cultures-Contexts -Matter/HIV-PNG.pdf [27] UNAIDS, “PNG UNGASS Country Report,” 2010. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2008/papua_new_guine a_2008_country_progress report_en.pdf [28] W. B. Miller, “Childbearing Motivations, Desires, and Intentions: A Theoretical Framework,” Genetic, Social & General Psychology Monographs, Vol. 120, No. 2, 1994, pp. 225-255. [29] M. Perugini and R. P. Bagozzi, “The Distinction between Desires and Intentions,” European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2004, pp. 69-84. doi:10.1002/ejsp.186 [30] N. McDowell, “Reproductive Decision Making and the Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA  Determinants of Fertility Desires among HIV Positive Women Living in the Western Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea Copyright © 2011 SciRes. WJA 207 Value of Children in the Rural Papua New Guinea,” Papua New Guinea Institute of Applies Social and Eco- nomic Research, Port Moresby, 1981. [31] S. Nakayiwa, B. Abang, L. Packel, et al., “Desire for Children and Pregnancy Risk Behaviours among HIV- Infected Men and Women in Uganda,” AIDS and Behav- ior, Vol. 10, Suppl. 1, 2006, pp. 95-104. doi:10.1007/s10461-006-9126-2 [32] N. Ko and M. Muecke, “Reproductive Decision-Making Among HIV Positive Couples in Taiwan,” Journal of Nursing Scholarship, Vol. 37, No. 1, 2005, pp. 41-47. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00008.x [33] P. Oosterhoff, N. Anh Thu, N. Hnah Thuy, et al., “Hold- ing the Line: Family Responses to Pregnancy and the De- sire for a Child in the Context of HIV in Vietnam,” Cul- ture, Health and Sexuality, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2008, pp. 403-416. doi:10.1080/13691050801915192 [34] S. Garap, “Kup Women for Peace: Women Taking Action to Build Peace and Influence Community Decision Mak- ing,” State, Society and Governance in Melanesia, 2004. http://dspace-prod1.anu.edu.au [35] M. Maier, I. Andia, N. Emenyonu, et al., “Antiretroviral Therapy Is Associated with Increased Fertility Desires, but Not Pregnancy or Live Birth, among HIV+ Women in the Early HIV Treatment Program in Rural Uganda,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 13, Suppl. 1, 2009, pp. 28-37. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9371-7 [36] S. Toft, “Domestic Violence in Papua New Guinea,” Law Reform Commission of Papua New Guinea, Port Mo- resby, 1985. [37] C. Bradley, “Family and Sexual Violence in Papua New Guinea: An Integrated Long-Term Strategy,” Report to the Family Violence Action Committee of the Consulta- tive Implementation and Monitoring Council, Discussion Paper No. 84, Institute of National Affairs, Port Moresby, 2001. [38] R. A. da Silverira, G. A. Fonsechi-Carvasan, M. Y. Ma- kuch, et al., “Factors Associated with Reproductive Op- tions in HIV-Infected Women,” Contraception, Vol. 71, No. 1, 2004, pp. 45-50. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.07.001

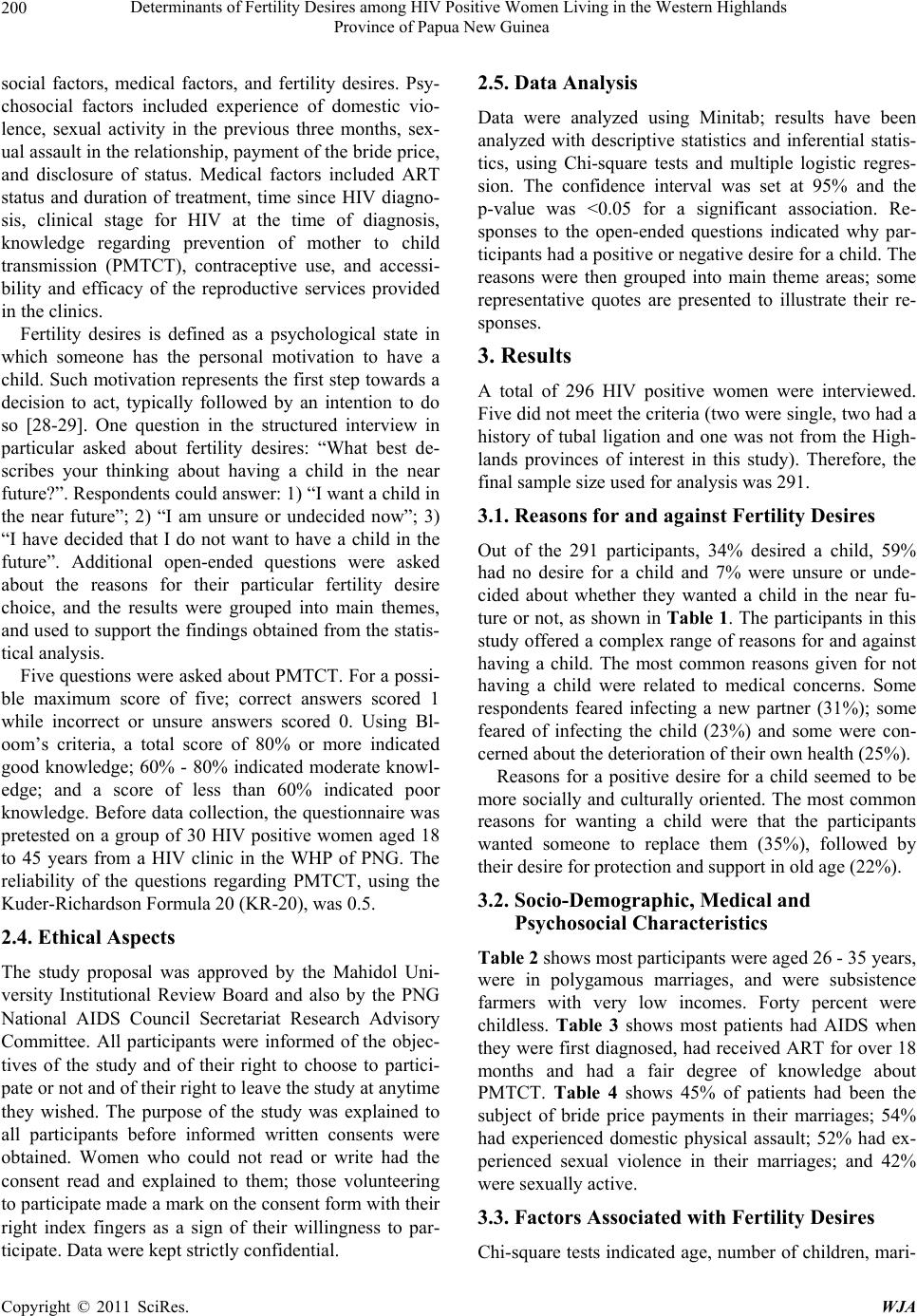

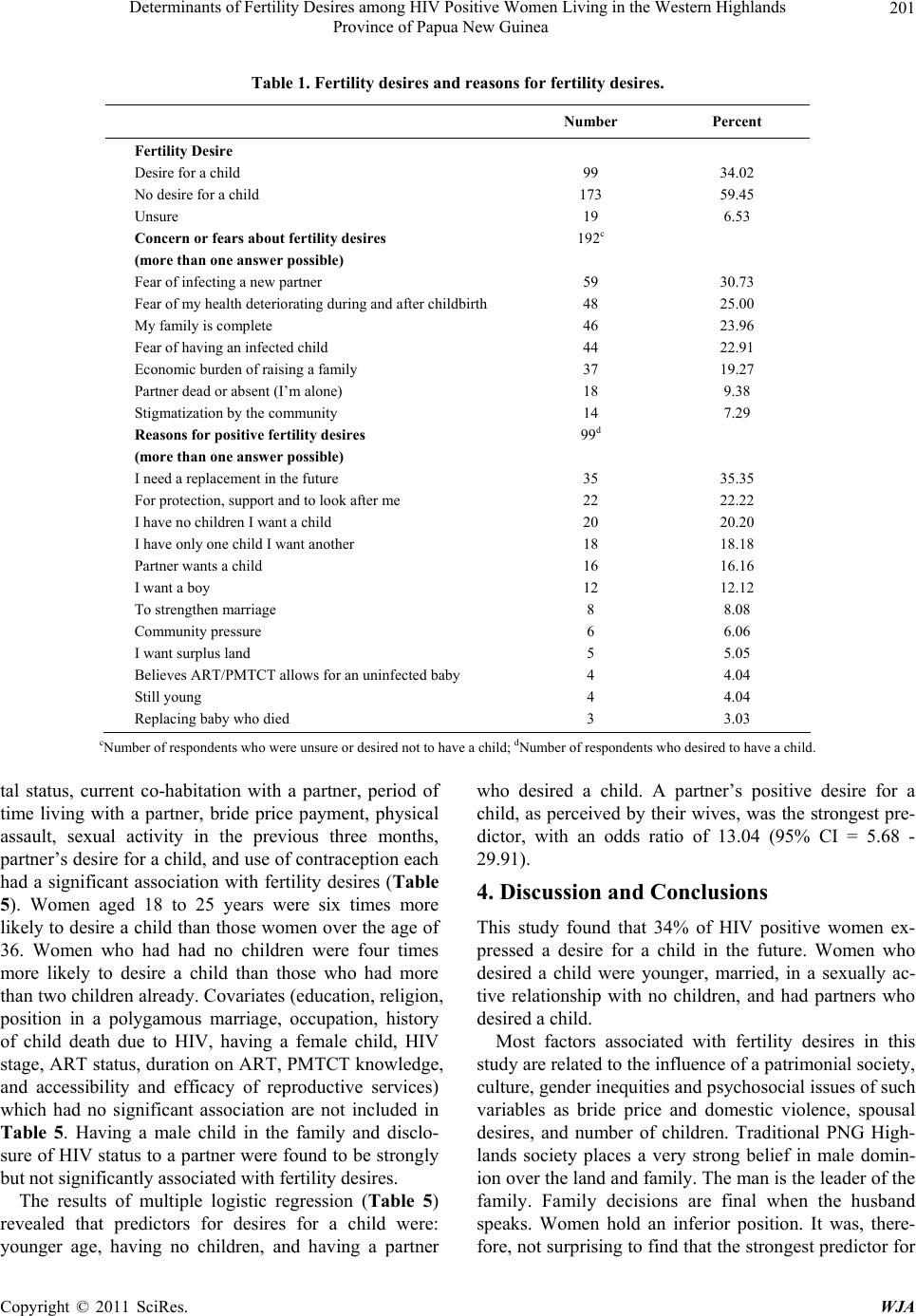

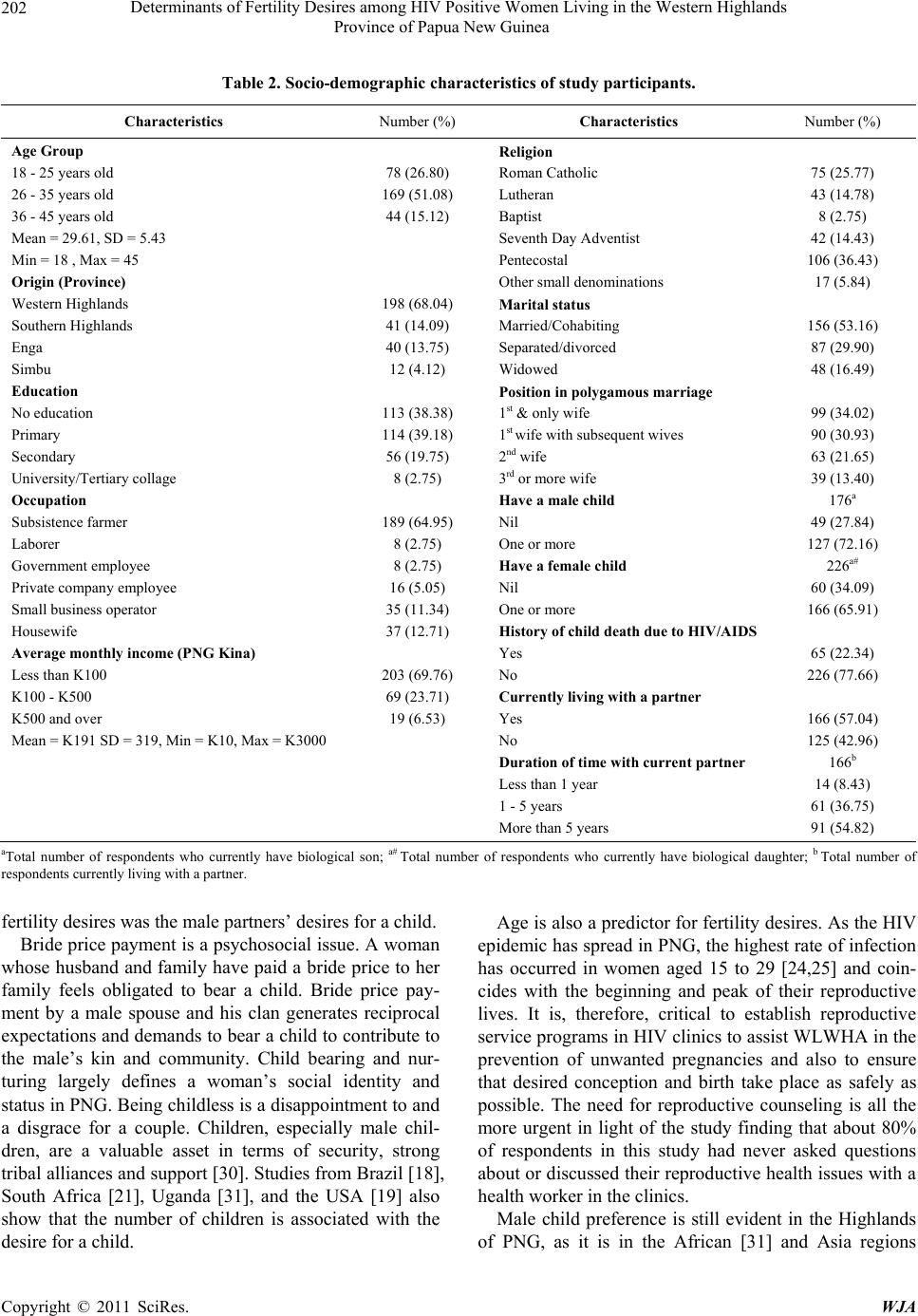

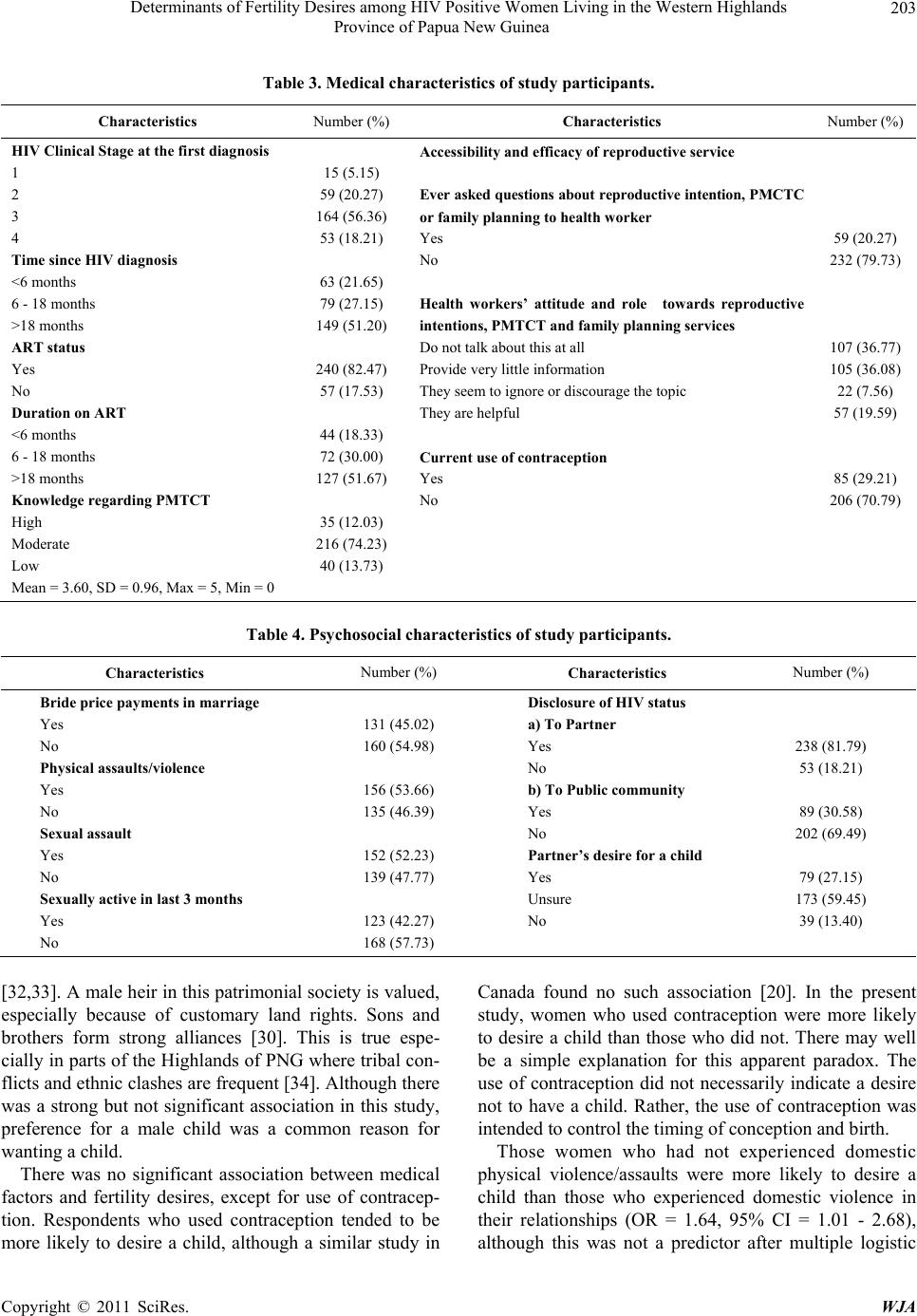

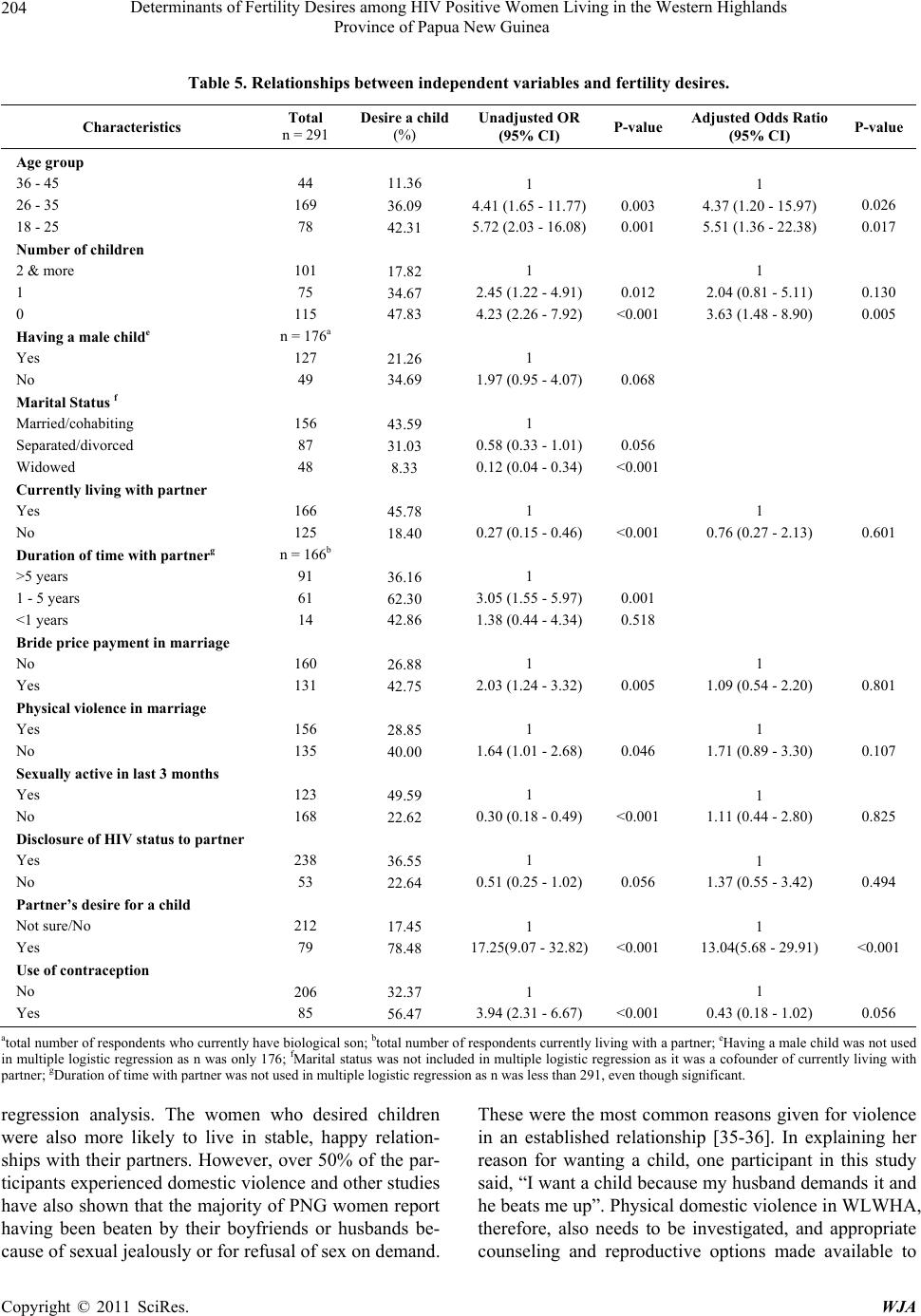

|