Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.9, 917-924 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.29138 Psychologists’ Diagnostic Processes during a Diagnostic Interview Marleen Groenier1, Vos R. J. Beerthuis2, Jules M. Pieters3, Cilia L. M Witteman4, Jan A. Swinkels5 1Instructional Technology, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands; 2Psychiatry, GGZ inGeest, Amstelveen, The Netherlands; 3Curriculum Design & Educational Innovation, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands; 4Diagnostic Decision Making, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; 5Adult Psychiatry, AMC de Meren, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Email: m.groenier@utwente.nl Received September 20th, 2011; revised October 23rd, 20 11; accepted November 26th, 2011. In mental health care, psychologists assess clients’ complaints, analyze underlying problems, and identify causes for these problems, to make treatment decisions. We present a study on psychologists’ diagnostic processes, in which a mixed-method approach was employed. We aimed to identify a common structure in the diagnostic processes of different psychologists. We engaged an actor to simulate a client. Participants were asked to per- form a diagnostic interview with this “client”. This interview was videotaped. Afterwards participants first wrote a report and then were asked to review their considerations during the interview. We found that psychologists were comprehensive in their diagnostic interviews. They addressed the client’s complaints, possible classifica- tions, explanations, and treatments. They agreed about the classifications, more than about causal factors and treatment options. The content of the considerations differed between the interviews and the reports written af- terwards. We conclude that psychologists continuously shifted between diagnostic activities and revised their decisions in line with the dynamics of the interview situation. Keywords: Clinical Decision Making, Diagnostic Interview, Stimulat ed Recall, Simulated Patient Introduction Psychological assessment is a diagnostic decision making process aimed at describing, classifying, explaining, predicting, and often also changing the behavior of a client (Fernández- Ballesteros, 1999). The result of the diagnostic process is an integrated representation of a client’s complaints and problems together with an explanation for the problems and a treatment proposal (Nelson-Gray, 2003). Guidelines have been developed to support psychologists in structured gathering and interpreting diagnostic information (see e.g. Groth-Marnat, 2003; Nezu & Nezu, 1995) to make sure that a thorough assessment is carried out and correct diagnostic decisions are made to reach the most adequate treatment proposal. Unfortunately, as Garb (1998) concluded, reliability and validity of these diagnostic decisions are low, although the final treatment proposals are often ade- quate. An explanation is provided in studies showing that psy- chologists do not always carry out all parts of the diagnostic process appropriately, even when explicitly asked to do so (Eells, Kendjelic, & Lucas, 1998; Groenier, Pieters, Hulshof, Wilhelm, & Witteman, 2008). In most of these studies assess- ment situations were artificial, and it remains unclear whether psychologists in actual practice would perform and report all parts of the diagnostic process. The current study is aimed at identifying common structures in psychologists’ diagnostic in- formation gathering processes in an authentic assessment situa- tion. The diagnostic process involves using different instruments, such as tests, interviews, and observations, as well as perform- ing different diagnostic activities, such as diagnostic classifica- tion and diagnostic formulation (Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2001). Diagnostic classification and diagnostic formulation are essential in the diagnostic process and described in many pre- scriptive diagnostic decision models (e.g. Nezu & Nezu, 1995; De Bruyn, Ruijssenaars, Pamijer, & Van Aarle, 2003). These models have been introduced to support psychologists in struc- turing the diagnostic process. The underlying assumption is that psychologists should adhere to a systematic inquiry method, by generating and testing hypotheses, to obtain relevant knowledge about a client (Haynes, Smith, & Hunsley, 2011). Also, these prescriptive models require psychologists to perform a set of distinct diagnostic activities in a specific sequence. Despite differences between these models (e.g. see Groth-Marnat, 2003; Nezu & Nezu, 1995), there are important commonalities in the kind and order of the diagnostic activities. First, the client’s complaints and referral question are identi- fied and analyzed (referred to as Complaint Analysis). Second, the severity of the client’s problems is assessed and the prob- lems are grouped into a disorder (Diagnostic Classification). Third, possible explanations for the problems are generated and tested, and the psychologist develops an integrated client model (Diagnostic Formulation). Finally, based on the integrated model a treatment is selected (Treatment Selection). These four activities are performed iteratively throughout the diagnostic process. Client models may differ depending upon psychologists’ theoretical orientations (see Eells, 2007, for an overview). For example, behavior therapy models emphasize relationships between antecedents and consequences, cognitive therapy models emphasize dysfunctional attitudes and thoughts, and psychodynamic models emphasize core conflictual relation- ships (cf. Persons, 1991). However, the main goal of diagnostic formulation is the same in all models: to identify and analyze  M. GROENIER ET AL. 918 causal factors and mechanisms underlying client problems (Haynes, Smith, & Hunsley, 2011; Westhoff, Hagemeister, & Strobel, 2007). In actual practice the information gathered is often incom- plete and ambiguous, problems can be explained by multiple causes (Haynes, Mumma, & Pinson, 2009), and the relation between diagnosis and treatment is far from obvious (Lichten- berg, 1997). Decision makers, i.c. psychologists, will then re- sort to efficient strategies that limit the amount of processing needed (Smith & Gilhooly, 2006; Garb, 2005; Gigerenzer, 2000). Indeed, earlier studies (e.g. Bus & Kruizenga, 1989; Groenier et al., 2008) pointed out that psychologists did not follow the resource-demanding formal rules of hypothesis gen- eration and testing. They tended to rely on routine and to focus on analyzing the client’s complaints and problems and selecting a treatment method, rather than on generating and testing pos- sible explanations for problems. These studies suggest that psychologists’ diagnostic processes are adapted to the con- straints of clinical practice rather than to the formal rules (cf. also Eells, Kendjelic, & Lucas, 1998). In this study we do not aim to test whether heuristic processing or following rules is the better process in terms of treatment utility, but we aim to find the structure in psychologists’ diagnostic processes. Previous studies have predominantly used written case de- scriptions or required written case formulations (see also e.g. Eells, Lombart, Kendjelic, Turner, & Lucas, 2005; Hillerbrand & Claiborn, 1990) instead of more authentic assessment tasks, as used in the current study where we engaged an actor to por- tray a client. This is a major advantage of our study, since the use of more authentic, ecologically valid assessment situations can contribute to identifying and understanding diagnostic processes in actual practice. Also, most studies have used only one method to examine the diagnostic process, thereby limiting comparability of results from studies using different methods, a limitation we overcome by using different methods. The Current Study The purpose of this study is to investigate psychologists’ di- agnostic activities in a authentic assessment situation represen- tative of psychological practice, using a mixed-method ap- proach. First (phase I), psychologists performed a diagnostic interview with a simulated client. Second (phase II), they wrote a report summarizing their findings. Third (phase III), we used stimulated recall in which psychologists reviewed the videotape of their diagnostic interview (cf. Kagan, Krathwohl, & Miller, 1963). The innovative design of the study allows us to study the assessment process in three different ways, based on an authen- tic diagnostic interview, the report, and the stimulated recall, tracing the diagnostic activities of each participant. This design is closely related to the approach suggested by Caspar (1997) for studying psychologists’ diagnostic processes, combining experimental and naturalistic research methods. We expected that: 1) Psychologists would not perform all of the prescribed di- agnostic activities described above during the diagnostic inter- view (cf. Groenier et al., 2008); 2) Psychologists would reflect on all diagnostic activities in the stimulated recall session, since they would post hoc attempt to “fill the gaps of their developing theory” (Brammer, 1997: p. 345) about the client; 3) The report would be more concise than the stimulated re- call, given its summarizing nature; 4) The contents of the report and stimulated recall would be similar. Psychologists would describe their final decisions on diagnostic classification, diagnostic formulation and treatment selection in the written report, thereby discarding some of the options they would have reflected on during the stimulated recall. Method Participants Psychologists who were part of the active networks of the first and second author were invited to participate. Participants came from all over The Netherlands and included certified clinical psychologists (n = 17), psychologists in training for certification (n = 6) and psychology students who were doing their final internship (n = 4). In total 27 psychologists partici- pated, aged between 22 and 65 years (M = 44.9, SD = 14.3); 12 male (mean age = 54.9, SD = 6.5) and 15 female (mean age = 36.9, SD = 13.8). On average, the participants had 14.8 years of work experience (SD = 12.8, Median = 12.0, range = 0 - 35 years). We found no significant effect of experience on the type and sequence of decisions, therefore, this factor was excluded from further analyses. Participants either worked in a mental health care centre (74%) or in a private practice (26%), and they mainly worked with adults (89%). Participants’ theoretical backgrounds were diverse. The majority (56%) did not work from any specific theoretical background. A previous study (Groenier et al., 2008) showed that theoretical background, together with other background variables, explained less than 10% of variance in activities psychologists would perform. The Diagnostic Interview All participants interviewed one and the same actor, who portrayed the same client throughout. Participants were told that they would either talk to an actor or to an actual patient. In addition, the client role was based on a real client with a de- pressive disorder without psychotic features, and adapted to the actor’s personal situation. To ensure identical performance across interviews, the actor received intensive training before the experiment, reread the script each time prior to being seen by a new participant, and was given feedback about the consis- tency of his performance after each interview. Procedure Before starting the interview with the actor, participants re- ceived information about the client’s name, gender, date of birth, residence, reason for referral by the family doctor (de- pressive and suicidal thoughts), the client’s occupation, psychi- atric history (none), marital status (married), number of chil- dren (two, a boy aged 16 and a girl aged 14), physical history (recently diagnosed with arteriosclerosis), current medication (no antidepressants), and the request from the family doctor for assessment and further treatment. Participants were given the instruction to “read the referral letter and interview the client as you would do in your own practice”. In phase I of the study, participants interviewed the simulated client for at most thirty minutes. The interview was videotaped. The participants were allowed to take notes during the inter- view, which enhanced authenticity. In phase II, participants wrote a report, and were required to give a diagnostic classifi- cation (DSM-IV classification; APA, 2000), a diagnostic for- mulation, and a treatment proposal. Phase II lasted a maximum of 15 minutes. In phase III, the stimulated recall session, par-  M. GROENIER ET AL. 919 ticipants were instructed to watch the videotape of their diag- nostic interview and to reflect on their own process by reporting any thoughts they had had during the actual interview. Duration varied from 30 to 90 minutes. The stimulated recall session started with two standard questions from the experimenter: 1) What did you think when you read the referral letter from the family doctor, and 2) What did you think when you first saw the client? Each time the participants indicated that they re- membered a thought, the experimenter stopped the video and the participant verbally reported it. When participants did not report anything for more than two minutes, the experimenter reminded them to verbalize their thoughts. The stimulated re- call session was recorded on videotape. Finally, participants answered questions about their back- ground (gender, age, work experience, theoretical orientation, work setting, and time spent on treating clients). Participants received a gift, i.e. a game or a gift certificate, for their partici- pation. Coding We developed one coding schema to assess the number of questions, remarks, and reflections related to the diagnostic activities during the diagnostic interviews and stimulated recall sessions as well as evaluate the contents of the diagnostic ac- tivities described in the reports. This coding schema was based on the Diagnostic Cycle (DC; De Bruyn et al., 2003). We chose the DC because it provides a complete and comprehensive in- ventory of the diagnostic activities psychologists are expected to perform. The schema consisted of five categories, described below, and the first four correspond with the diagnostic activi- ties that diagnostic decision models have in common: 1) Com- plaint Analysis, 2) Diagnostic Classification, 3) Diagnostic Formulation, 4) Treatment Selection, and 5) Other. Complaint Analysis consisted of complaints reported by the client, complaints and symptoms inferred by the participant (such as symptoms of depression, libido, suicidal thoughts, manic episodes, psychotic features, anxiety), and the client’s verbal and non-verbal behavior. Diagnostic Classification consisted of the type and severity of the disorder (e.g. a DSM-IV classification), the client’s awareness of an illness or a differential disorder. Diagnostic Formulation consisted of potential stressors and protective factors related to the client’s psychiatric history, family, physical or social history, the client’s biography, per- sonality or to biological/genetic factors. This category could also consist of descriptions of a psychological, biological or socio-cultural mechanism explaining (the development of) the client’s disorder. Treatment Selection consisted of the client’s or the partici- pant’s expectations about treatment options, a future therapeutic intervention, treatment methods and goals, suicide prevention, the therapeutic intervention’s intensity, medication, the client’s motivation for treatment, or performing therapeutic interven- tions during the diagnostic interview. The category Other consisted of utterances about the thera- peutic relationship, the client’s personal details, reason for re- ferral, substance abuse, duration of the interview, awareness of the test situation, supportive remarks, further assessment, own method of working, (counter) transference, and non-classifiable remarks. Examples of each of the categories are described in Appendix A. Both the protocols of the diagnostic interviews with the actor and of the stimulated recall sessions with the participants were first divided into meaningful units and then coded into one of the five ca tegories. We defined a meaningful unit as a sentence or part of a sentence that expresses a single idea and receives only one code. The computer program Sequence Viewer (Dijkstra, 2002) was used to divide the diagnostic interviews and stimulated recall sessions into meaning units and consecu- tively assign them to one of the coding categories. A standard coded diagnostic interview and a standard stimulated recall protocol were created by the first and second author. These were used to train coding assistants and to assess each coder’s reliability afterwards. The reports were already structured according to the catego- ries Diagnostic Classification, Diagnostic Formulation and Treatment Selection (see Method, Procedure). The categories Complaint Analysis and Other were not used in the reports. Reliability of the Coding For the diagnostic interview, six independent coding assis- tants (bachelor degree medical and psychology students) were used. Coder’s reliability was assessed by Sequence Viewer’s Delta (Dijkstra & Taris, 1995). This statistic calculates agree- ment taking differences in the number of meaningful units identified into account. An advantage of this statistic is thus that reliability only needs to be calculated once, for the seg- mentation and coding together instead of separately. Delta var- ied from .75 to .85 and was considered satisfactory. For the segmentation and coding of the stimulated recall ses- sions, two independent coding assistants (bachelor degree psy- chology students) and the first author were used. Reliability varied from .75 to .90, which was quite satisfactory. Analysis Due to malfunctioning of the digital compact discs used to record the diagnostic interviews, three of the diagnostic inter- views and two of the stimulated recall sessions had to be re- moved from further analysis. This resulted in 24 participants for the diagnostic interview and 25 participants for the stimulated recall. The mean percentage of meaningful units for each diagnostic activity was calculated both for the interview and for the recall. To examine differences between the diagnostic interview and the stimulated recall, we used the non-parametric Wilcoxon test. For the diagnostic interview and the stimulated recall separately, we examined differences in the percentages of each diagnostic activity using Friedman tests. Wilcoxon tests were used to fol- low up on significant findin gs. A Bonferroni procedure was used to maintain an overall significance level of .05. Effect sizes were measured using r (-scorenumber of observa tionsz; see Field, 2000). To compare the content of the diagnostic activities between the report and the stimulated recall session, we counted the number of participants who described (report) or reflected on (stimulated recall session) a Diagnostic Classification (includ- ing a differential diagnosis), Diagnostic Formulation (including potential stressors and explanatory mechanisms), and Treat- ment Selection (including treatment method and goal). A dif- ferent measure was used compared to assessing the reliability of coding to assess the agreement between the report and stimu- lated recall because for this analysis we did not assess interrater reliability. We calculated percentage agreement between the content of the report and the stimulated recall as the number agreed on divided by the number disagreed and agreed on taken together.  M. GROENIER ET AL. 920 Results The mean total number of meaningful units, a sentence or part of a sentence that expresses a single idea (see Method), was 195.2 (SD = 46.2, range = 109 - 290) for the diagnostic interview and 96.44 (SD = 40.76, range = 29 - 192) for the stimulated recall session. The mean percentages of meaningful units for each diagnostic activity are described in Table 1 for both the diagnostic interview and stimulated recall session. Diagnostic Interview Compared with Stimulated Recall Session As can be seen in Table 1, there were differences in percent- ages of meaningful units in the four diagnostic activities (Com- plaint Analysis, Diagnostic Classification, Diagnostic Formula- tion and Treatment Selection). For the stimulated recall session the percentages of meaningful units were significantly higher for the activities Complaint Analysis (z = –3.29, p < .001, r = –.47), Diagnostic Classification (z = –3.10, p < .001, r = –.45) and Treatment Selection (z = –2.66, p = < .001, r = –.38). The percentage of meaningful units for Diagnostic Formulation was significantly lower (z = –4.29, p < .001, r = –.62) for the stimu- lated recall session. The percentage of meaningful units of the category other (see Appendix A) did not differ significantly (r = –.06). Diagnostic Activities in the Diagnostic Interview Complaint Analysis, Diagnostic Classification, Diagnostic Formulation, and Treatment Selection differed from each other in the mean percentage of meaningful units (χ2(4) = 84.879, N = 24, p < .001). The diagnostic activities Complaint Analysis and Diagnostic Formulation did not differ significantly from each other (r = .03). Both activities differed significantly from every other activity (all z < –3.702, all p < .001, all r < –.53). All participants asked or remarked at least once about Com- plaint Analysis, Diagnostic Formulation, and Treatment Selec- tion. Out of 24 participants, 17 discussed the classification with the client. Diagnostic Activities in the Stimulated Recall Session Complaint Analysis, Diagnostic Classification, Diagnostic Formulation, and Treatment Selection differed from each other in the mean percentage of meaningful units (χ2(4) = 83.322, N = 25, p < .001). The diagnostic activity Complaint Analysis differed significantly from every other type of activity (all z < –3.589, all p < .001, all r < –.51). Diagnostic Formulation dif- fered significantly from Diagnostic Classification (z = –.3.589, p < .001, r = –.51), but not from Treatment Selection (r = –.28). Treatment Selection did not differ significantly from Diagnostic Classification ( r = –.19). All participants reflected at least once on Complaint Analysis and Diagnostic Formulation. Out of 25 participants, 21 and 22 participants reflected at least once on Diagnostic Classification and Treatment Selection respectively. Content of Diagnostic Activities: From Interview to Report Diagnostic Classification Participants reflected on eight different Diagnostic Classifi- cations for the client’s problems during the stimulated recall sessions (range = 0 - 5) and described 10 DSM-IV Diagnostic Classifications on Axis I and II in the reports (range = 0 - 3). In Table 2 the content of these classifications and the numbers of participants reflecting on or describing each classification are displayed. Most participants (84%) considered the same classification: depression. Seven participants (28%) reflected on a differential diagnosis (range = 0 - 4). Apart from depression, which was always stated as being present by these participants, other clas- sifications (psychosis, anxiety disorder, manic episode, person- ality disorder, adjustment disorder, obsessive-compulsive dis- order and dysthymic disorder) were considered as differential diagnoses or were discarded during the interview. Percentage agreement between the Diagnostic Classifications reflected on during the stimulated recall sessions and those described in the reports was 38%. Diagnostic Formulation Participants reflected on 11 different potential stressors and 13 different explanatory mechanisms during the stimulated recall sessions. They described nine different potential stressors and seven different explanatory mechanisms in the Diagnostic Formulations (see Table 3). Three participants did not reflect on the conflict at work or the client’s physical illness. The majority of participants re- flected on (stimulated recall session) and described (report) more than one type of potential stressor (92%, range = 0 - 8, and 80%, range = 0 - 3, respectively). The minority of participants reflected on and described more than one type of explanatory mechanism (24%, range = 0 - 4, and 12%, range = 0 - 3, respectively). Percentage agreement between the types of potential stress- ors reflected on during the simulated recall sessions and de- scribed in the written Diagnostic Formulations was 67%. Per- centage agreement for the explanatory mechanisms was 11%. Treatment Selection Participants reflected on 13 different types of treatment methods and/or goals during the stimulated recall sessions and Table 1. Mean percentage of meaningful units, Standard Deviations (SD) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for Each di- agnostic activity and type of method. Diagnostic Interview (n = 24) Stimulated R ecall Session (n = 25) Diagnostic Activity Mean SD CI Mean SD CI Complaint Analysis 25.3 7.8 22.0 - 28.632.5 6.5 29.8 - 35.2 Diagnostic Classification 1.6 1.6 0.8 - 2.2 4.8 4.3 3.0 - 6.6 Diagnostic Formulation 2 5.9 7.1 22.9 - 28.911.4 6.4 8.7 - 14.0 Treatm ent Selection 4.1 3.4 2.7 - 5.5 7.1 5.2 4.9 - 9.2 Other 43.2 9.0 39.4 - 47.044.2 12.1 39.2 - 49.2  M. GROENIER ET AL. 921 Table 2. Content of diagnostic classifications reflected on (Stimulated recall session) and described (Report). Content of diagnostic cl assifications Stimulated recall Report Depression, depressive episode or depressed mood 21 20 Psychosis or psychotic features 3 10 Anxiety disorder 3 Manic episode 2 (Avoidant) personality disorder or traits 2 5 Adjustment disorder 1 4 Obsessive -compulsive disorder or f eatures 1 1 Dysthymic disorder 1 Axis II diagnosis delaye d 17 Problems a t work 2 Loneliness 1 Life phase pro blems 1 Post-traumatic stress disorder 1 described 14 different types of treatment goals and methods in the treatment proposals of the reports (see Table 4). Nine participants (36%) reflected on more than one type of treatment method or treatment goal during the stimulated recall session (range = 0 - 3). About half of the participants (56%) described more than one type of treatment method in their re- ports (range = 0 - 3), while only 22% described more than one treatment goal (range = 0 - 3). The majority of participants (70%) described antidepressant or antipsychotic medication in the reports, while only two participants mentioned that topic during the stimulated recall session. Also, participants more often described specific therapies (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy) in the reports, while treatment goals were more often mentioned in the stimulated recall sessions. Percentage agree- ment between the treatment methods and goals reflected on during the stimulated recall sessions and those described in the treatment proposals was 37%. Conclusions and Discussion The current study investigated psychologists’ diagnostic processes during a diagnostic interview. Specifically, we aimed to examine whether psychologists would explicitly focus on identifying and classifying the client’s complaints, symptoms, and problems during a diagnostic interview, while implicitly reflecting on all diagnostic activities necessary to make treat- ment decisions. Furthermore, we examined whether the content of psychologists’ reports matches with the content of the activi- ties considered during the interview. We found that psycholo- gists perform and consider all diagnostic activities throughout the diagnostic interview. Also, content of psychologists’ reports was only partly similar to the content of diagnostic activities considered during the interview with the simulated client. Our results emphasize the adaptive nature of the diagnostic decision making process in actual clinical practice as a con- tinuous shifting between diagnostic decision activities. Psy cholo- gists analyzed the client’s complaints and symptoms, consid- ered possible classifications, started a diagnostic formulation, and planned the treatment. They continuously reconsidered Table 3. Content of diagnostic formulations reflected on (Stimulated recall session) and described (Report). Content of diagnostic formulation Stimulated recall Report Potential stressors or predi sposing expe riences Conflict or problems at work 15 15 Physical illness 15 21 Personality tra its 14 1 Genetic factors 11 7 Family o f or i gin and/or affective neglect in childhood 9 2 Current role in own family 6 1 Experiences of loss 5 Upcoming surgery 5 4 Cycling accident 3 2 Relationship problems 3 Other neurological or physical conditions 2 Lack of social support 1 Explanatory mechanisms Physical problems, head injury, or medication 9 Inefficient coping with quicker, younger colleague s at work 3 Phase of life problems 3 Losing social support or not accepting social support 2 Dysfunctional thoughts 2 Reactive to multiple curre n t, but unidentified, stressors 2 2 Psychological conflict about father 1 Psychological conflict about male identi ty 2 Insecurity or fear about failing b od y 1 2 Burn-out 1 Relationship problems 1 Transgenerational problems 1 Emotion regula ti on 1 Setting high d emands for one self 3 (Avoidant) coping style 2 Reversal of caregiver’s role 1 Psychologic al “hurt ” 1 Fear of bec oming like hi s mother 1 these diagnostic activities throughout the whole process. Agree- ment about possible explanations for the problems seemed to be low and psychologists’ decisions described in the reports dif- fered from their reflections on the diagnostic activities reflected on while talking to a client. Psychologists tended to agree with each other about diagnos- tic classification, while agreement on diagnostic formulation (su ch as explanatory mechanisms) and treatment options seemed to be moderate to low. Diagnostic classifications, diagnostic formulations, and treatment options considered during the in- terview partly recurred in the reports, contrary to our expecta-  M. GROENIER ET AL. 922 Table 4. Content of treatment selection reflected on (Stimulated recall session) and described (Report). Content of treatment methods and goa ls Stimulated recall Report Ask client about goals or expectations 6 3 Referral to psychiatrist 4 8 Antidepressant or antipsyc hotic medication 2 19 Strengthen clie nt’s own responsibility for solving problems 2 Coping with s is ter’s de p ression 2 Strengthen role as a father 1 Consult others and/or explore other topics 1 11 Suicide contract or attend to suicide risk 1 8 Hospitalization 1 System or f amily therapy, (involve partner) 1 7 Crisis intervention 1 Change daily routine 1 2 Coping with life phase problems 1 Cognitive be h avioral therapy 8 Interpersonal therapy 2 Supportive therapy 2 Psychotherapy not otherwise spec i f ied 1 Perform relaxation or activation exercises 4 Attend to negative thoughts or feelings 3 tions. We found a larger number of diagnostic classifications and treatment goals and methods in the report and a smaller number of potential stressors and explanatory mechanisms compared to the stimulated recall. A possible explanation for the differences in the content could be that the report elicited a different task expectation compared to the stimulated recall session. Writing a report is a reflective task and psychologists might make inferences based upon the information they have gathered during the diagnostic interview. Also, it is commonly used to communicate assessment findings to others, which re- quires psychologists to make their considerations explicit in terms that are commonly shared (such as DSM-IV classifica- tions) and easily understandable. The findings in this study confirm previous findings from a study by Groenier et al. (2008), which showed that psycholo- gists judge an analysis of the client’s complaints and symptoms to be more important than diagnostic formulation. The prescrip- tions of for example the Diagnostic Cycle (De Bruyn et al., 2003) do not seem to be fully followed. An explanation for the inconsistency between what psychologists do and what they reflect back on could be that they iteratively gather information for later use. Psychologists might return to previous diagnostic activities later on in the diagnostic and treatment process for various reasons, e.g. to verify information, gather more specific information or adjust previous decisions. Another explanation could be that they gather information routinely. Guidelines prescribe which information should be collected, including information relevant for diagnostic formulation. Psychologists’ diagnostic processes seemed to be unstruc- tured and deviate from prescriptions of diagnostic decision models to some extent, however, the majority arrived at an appropriate diagnosis and reasonably comprehensive treatment plan. Most psychologists in the current study classified the client’s problems as a depression. Alternative diagnostic classi- fications did not seem to be discussed or considered very often in any part of the interview. Considering few alternative diag- nostic classifications is consistent with results from previous studies on psychiatric diagnoses (Garb, 1998; Haverkamp, 1993). An explanation could be that psychologists “satisfice” (Simon, 1957): as soon as they find a classification that suffi- ciently describes the client’s condition and differentiates be- tween treatments, they choose that classification and stop searching. They then seem to gather more information relevant to deciding between specific treatments. This can be inferred from the remarks and considerations about treatment selection, which psychologists already considered early on in the diag- nostic process, during a first interview with the client. Psychologists’ diagnostic processes in the current study show commonalities in the type of diagnostic activities deliberately performed and considered, despite differences in theoretical orientation and experience. They did consider a wide range of potential causal factors, explanatory mechanisms and treatment options for the same client and agreed less with each other about this kind of information than about the diagnostic classi- fication. These results are in line with results from a study by Müller (2011) on graphical representations of psychologists’ case formulations showing that psychologists consider multiple, interrelated causes to explain a disorder. Furthermore, Kuyken et al. (2005) found that reliability of diagnostic formulations decreased when more theory-driven inferences were made. Variations in judgments about treatment of depression have been found in medical decision making as well (Smith, Gil- hooly, & Walker, 2002). To cope with cognitive limitations in a dynamic situation psychologists adapt their diagnostic proc- esses in similar ways, they are boundedly rational (Gigerenzer, 2000). In the current study, an authentic assessment situation was used with a simulated client and time constraints to resemble clinical practice as much as possible. This assessment situati on closely resembles actual practice and can be regarded as exter- nally or ecologically valid. With a simulated client, realistic interaction is possible, non-verbal behavior can be observed and a therapeutic relationship can be established, in contrast to artificial task situations using written case descriptions. How- ever, there are also some limitations to our methodology and further studies may provide additional information. Although stimulated recall is designed to measure psychologists’ thoughts at the time of the actual diagnostic interview, thoughts after the fact may also be included. Therefore, the data are not an actual reflection of what happened, but are used to assess reflections on actions. We assumed that these reflections would not have changed much from the diagnostic interview and writing the report to the stimulated recall session, but they did differ between the reports and the stimulated recall session. This suggests that reflections might also have changed in be- tween the diagnostic and stimulated recall session. However, using alternative methods such as thinking aloud during the task would have disrupted the authenticity of the interview. The use of only one case describing a single disorder, de- pression, limits generalization of the results to other disorders. The time and labor intensive methods we used prohibited the inclusion of more cases, but in future research, multiple cases presenting different disorders could be used. The most impor- tant question for future studies is the effect of deviating from the prescribed guidelines for making diagnostic decisions on  M. GROENIER ET AL. 923 the quality of the decisions made and eventually on therapy outcome. Acknowledgements The research project was partially supported by a grant from the Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ (Foundation for Support, Christian Union for Care of Mentally Ill). We would like to thank our coding assistants, Anja Kuijer, Lotte Croese, Hilde Mees, Milou Kievik, Marjon Stijntjes, Ludwig Fritzsch, Petra Hagens, Helena Boering, and Gery Zoer for their hard work and enthusiasm for this project. Also, we would like to thank Stasja Draisma and Sander Overdevest for their time and support on working with the Sequence Viewer program. References American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th revised ed.). Washington, DC: Au- thor Brammer, R. (1997). Case conceptualization strategies: The relation- ship between psychologists’ experience levels, academic training, and mode of clinical inquiry. Educational Psychology Review, 9, 333-351. doi:10.1023/A:1024794522386 Bus, A. G., & Kruizenga, T. H. (1989). Diagnostic problem-solving behavior of expert practitioners in the field of learning disabilities. Journal of School Psychology, 27, 277-287. doi:10.1016/0022-4405(89)90042-3 Caspar, F. (1997). What goes on in a psychotherapist’s mind? Psycho- therapy Research, 7, 105-125. doi:10.1080/10503309712331331913 De Bruyn, E. E. J., Ruijssenaars, A., Pameijer, N. K., & Van Aarle, E. J. M. (2003). The diagnostic cycle. Learning from practice. Leuven: Acco. Dijkstra, W. (2002). Sequence viewer 3.0. Amsterdam: Department of Social Research Methods, Vrije Universite it. Dijkstra, W., & Taris, T. (1995). Measuring the agreement between sequences. Sociological Methods & Research, 24, 214-231. doi:10.1177/0049124195024002004 Eells, T. D. (2007). Handbook of psychotherapy case formulation (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. Eells, T. D., Kendjelic, E. M., & Lucas, C. P. (1998). What’s in a case formulation? Development and use of a content coding manual. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 7, 144-153. http://jppr.psychiatryonline.org/ Eells, T. D., Lombart, K. G., Kendjel ic, E. M., Turner, L. C., & Lucas, C. P. (2005). The quality of psychotherapy case formulations: A comparison of expert, experienced, and novice cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic therapists. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 579-589. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.579 Fernández-Ballesteros, R. (1999). Psychological assessment: Future challenges and progresses. European Psychologist, 4, 248-262. doi:10.1027//1016-9040.4.4.248 Fernández-Ballesteros, R., De Bruyn, E. E. J., Godoy, A., Hornke, L. F., Ter Laak, J., Vizcarro, C., Westhoff, K., Westmeyer, H., & Zac- cagnini, J. L. (2001). Guidelines for the assessment process (GAP): A proposal for discussion. European Journal of Psychological As- sessment, 17, 187-200. doi:10.1027//1015-5759.17.3.187 Field, A. (2000). Discovering statistics using SPSS for windows. Thou- sand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd. Garb, H. N. (1998). Studying the clinician: Judgment research and psychological assessment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Garb, H. N. (2005). Clinical judgment and decision making. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 67-89. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143810 Gigerenzer, G. (2000). Adaptive thinking: Rationality in the real world. New York: Oxford University Press. Groenier, M., Pieters, J. M., Hulshof, C. D., Wilhel m, P., & Witteman, C. L. M. (2008). Psychologists’ judgments of diagnostic activities: Deviations from a theoretical model. Clinical Psychology and Psy- chotherapy, 15, 256-265. doi:10.1002/cpp.587 Groth-Marnat, G. (2003). Handbook of psychological assessment (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Haverkamp, B. E. (1993). Confirmatory bias in hypothesis testing for client-identified and counselor self-generated hypotheses. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 40, 303-315. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.40.3.303 Haynes, S. N., Mumma, G. H., & Pinson, C. (2009). Idiographic as- sessment: Conceptual and psychometric foundations of individual- ized behavioral assessment. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 179- 191. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.12.003 Haynes, S. N., Smith, G. T., & Hunsley, J. D. (2011). Scientific founda- tions of clinical assessment. New York, NY: Routledge. Hillerbrand, E. T., & Claiborn, C. D. (1990). Examining reasoning skill differences between expert and novice counselors. Journal of Coun- seling & Development, 68, 684-691. www.counseling.org Kagan, N., Krathwohl, D. R., & Miller, R. (1963). Stimulated recall in therapy using video tape: A case study. Journal of Counseling Psy- chology, 10, 237-243. doi:10.1037/h0045497 Kuyken, W., Fothergill, C. D., Musa, M., & Chadwick, P. (2005). The reliability and quality of cognitive case formulation. Behavior Re- search and Therapy, 43, 1187-1201. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.007 Lichtenberg, J. W. (1997). Expertise in counseling psychology: A con- cept in search of support. Educational Psychology Review, 9, 221- 238. doi:10.1023/A:1024783107643 Müller, J. M. (2011). Evaluation of a therapeutic concept diagram. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27, 17-28. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000053 Nelson-Gray, R. O. (2003). Treatment utility of psychological assess- ment. Psychological Assessment, 15, 521-531. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.15.4.521 Nezu, C. M., & Nezu A. M. (1995). Clinical decision making in every- day practice: The science in the art. Cognitive and Behavioral Prac- tice, 2, 5-25. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(05)80003-3 Persons, J. B. (1991). Psychotherapy outcome studies do not accurately represent current models of psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 46, 99-106. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.2.99 Simon, H. A. (1957). Models of man: Social and rational. New York: Wiley. Smith, L., & Gilhooly, K. (2006). Regression versus fast and frugal models of decision-making: The case of prescribing for depression. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 265-274. doi:10.1002/acp.1189 Smith, L., Gilhooly, K., & Walker, A. (2002). Factors influencing pre- scribing decisions in the treatment of depression: A social judgement theory approach. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17, 51-63. doi;10.1002/acp.844 Westhoff, K., Hagemeister, C., & Strobel, A. (2007). Decision-aiding in the process of psychological assessment. Psychology Science, 49, 271-285. http://www.doaj.org/  M. GROENIER ET AL. 924 Appendix A Examples of the categories from the coding schema. Diagnostic Interview Stimulate d Recall Sessio n Report Complaint Analysis “So you feel like you are an old man already?” “You are going through some intense experiences.” “Do you fee l sad all day lo ng?” “I noticed his date of birth.” “He really looks depressed.” “I should ask ab out his suicidal thoughts.” N/A Diagnostic Classification “Your depression can also b e seen as a n illness.” “I am sure y ou are suffering from a depression.” “He has be en depressed for about two months now.” “Possibly a personality d is order as well.” “Depressi v e disorde r, severe.” “Single depressive episode.” “Depression w ith psychotic features.” Diagnostic Formulation “Did you ever experience a depressive episode before?” “Does depression run in the family?” “Is the arteriosclerosis a hereditary condition?” “Do you have any serious debts?” “You mentioned sports means a lot to you.” “What kind of education have you had ?” “Are you usually an optimistic person?” “To what extent did he get support from his father when he was young?” “He seems to have a hereditary defect.” “I try to find out more about the supp ort he ge t s from his family.” “His sense of wor thlessness w as increased by his own thoughts about the conflict at work.” “I wondered whether his cycling accident involved a head injury which might have caused his mood change.” “His depre s sion is a reaction to his loss of health.” “He has a p os it ive family history for depression.” “Depressi on trigger ed by his problems at wo rk and physical condition, possi bly complicated by medication us e.” “He feels a fraid about losing his health.” “He experiences a lack of support.” Treatment Selection “Would you be wi l ling to take antidepre s s ants?” “Depression can be treated.” “His condition can certainly be treated.” “I thought: I s hould offer him some future prospects.” “Refer to a psychiatrist.” “Medication first, then cognitive-behavioral therapy.” Other “I read in the referral lette r t hat you have t alked to your physician.” “We have only 5 minutes le ft .” “I would refer him to a psychiatrist.” “I usually start an interview with questions about the referral letter.” N/A

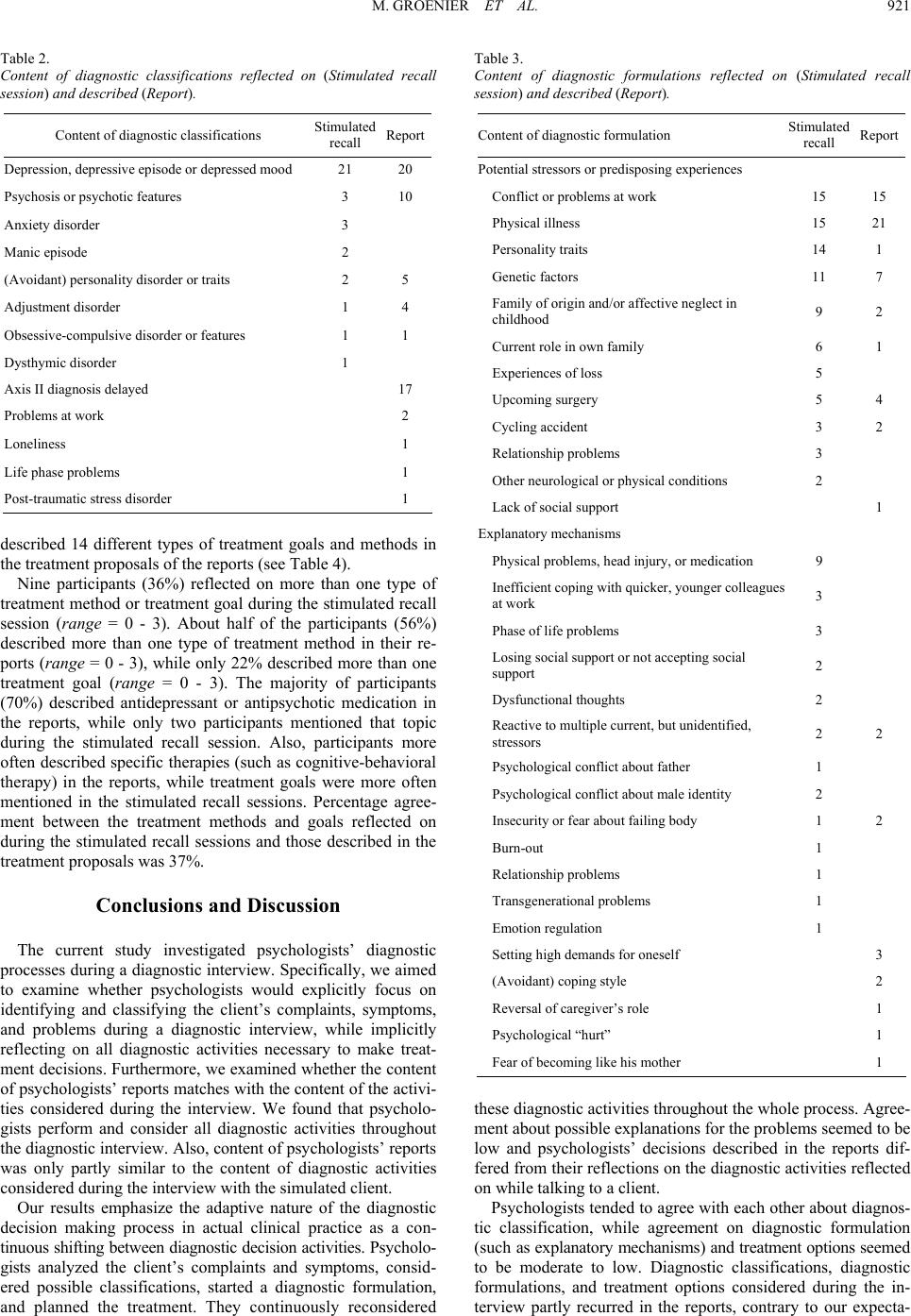

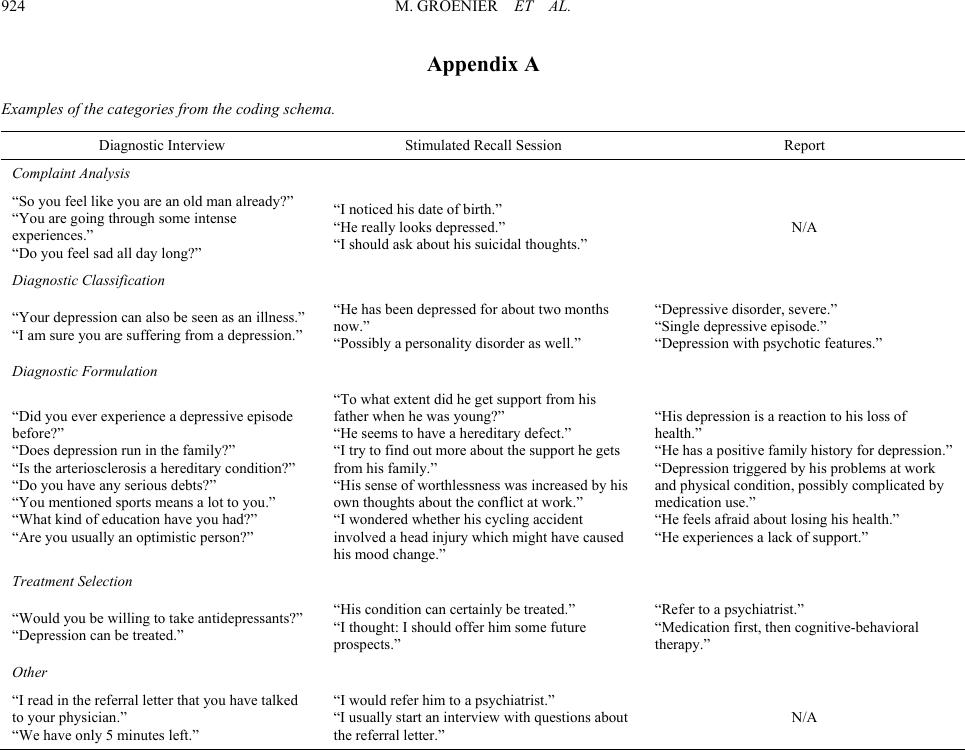

|