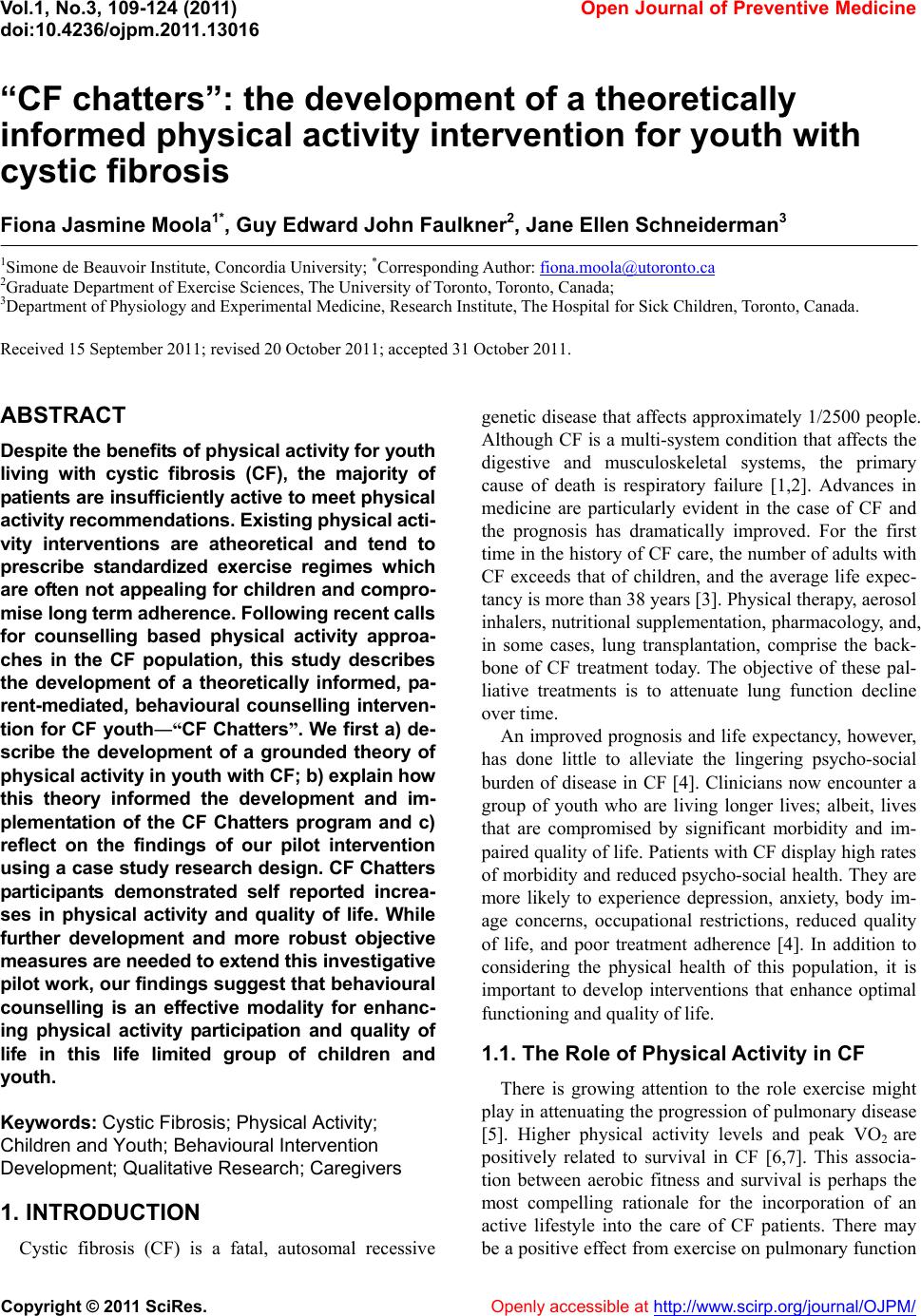

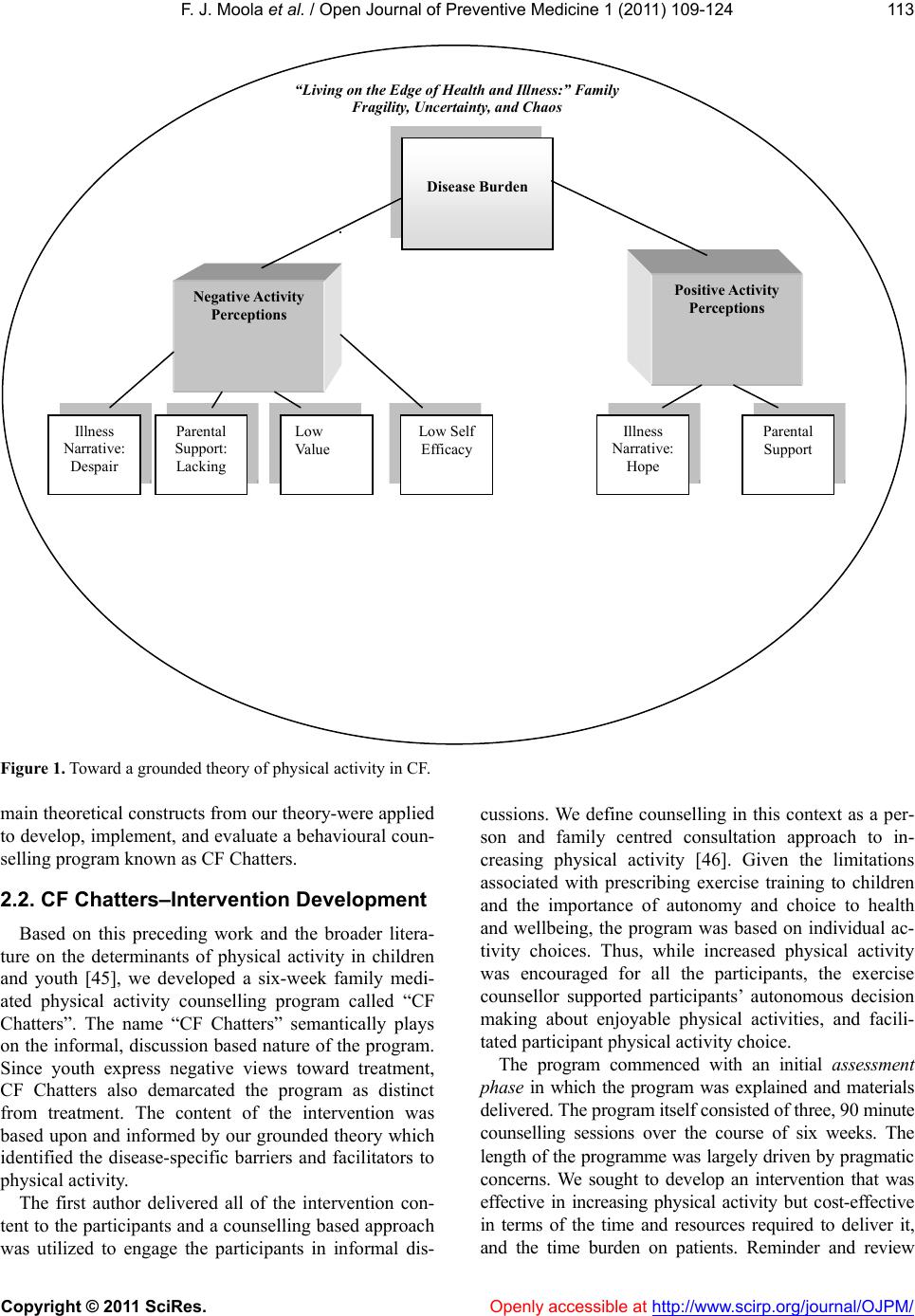

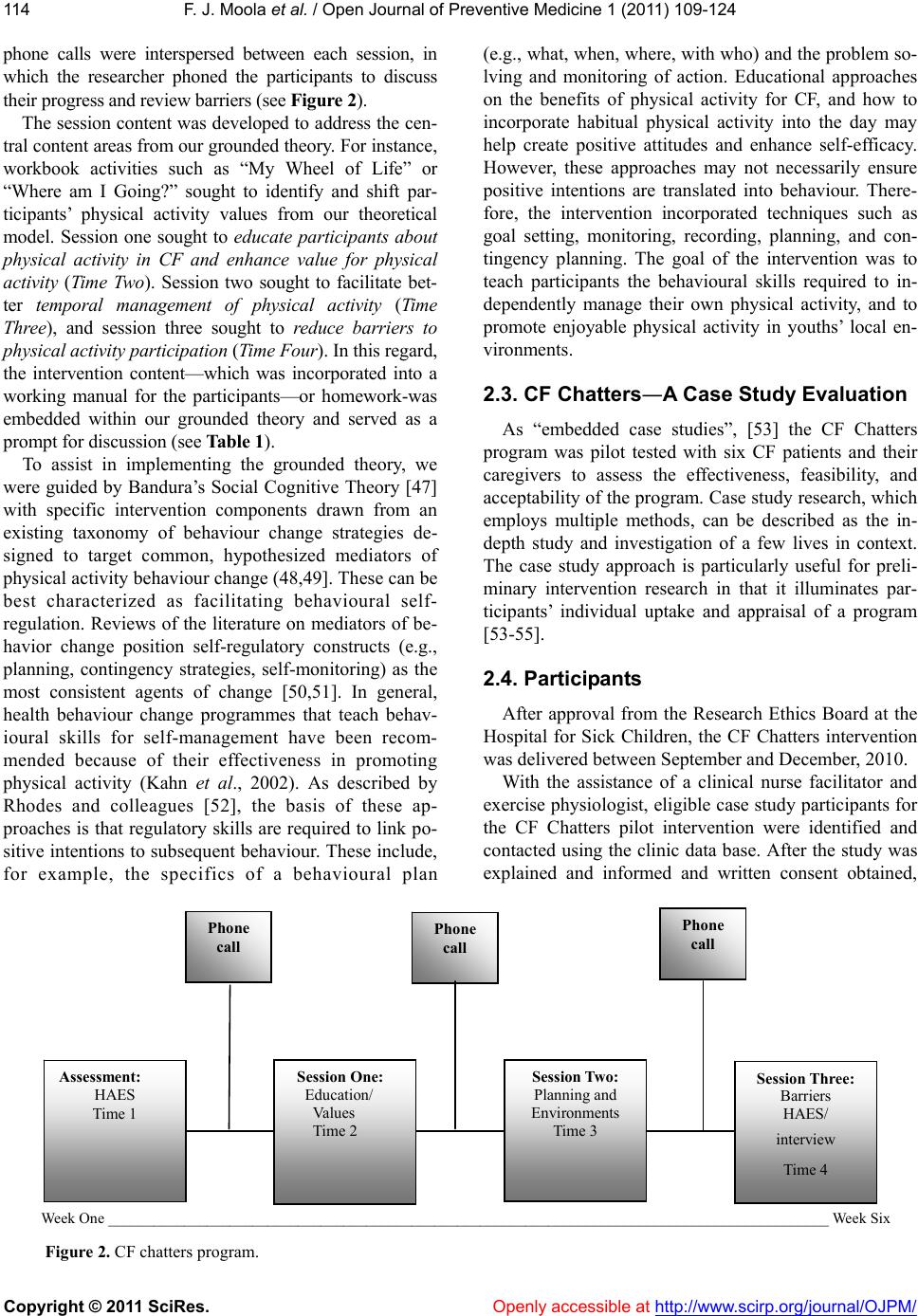

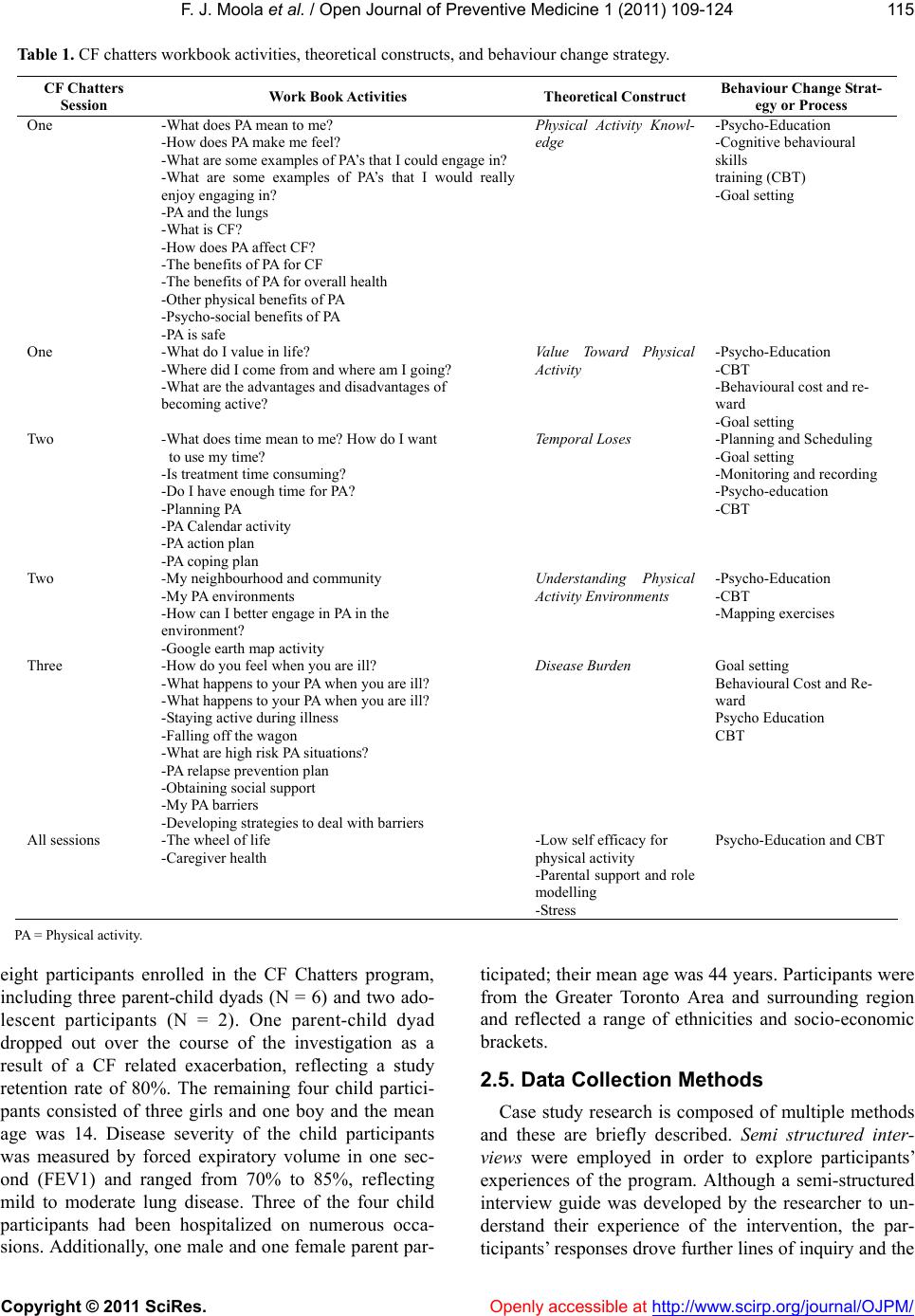

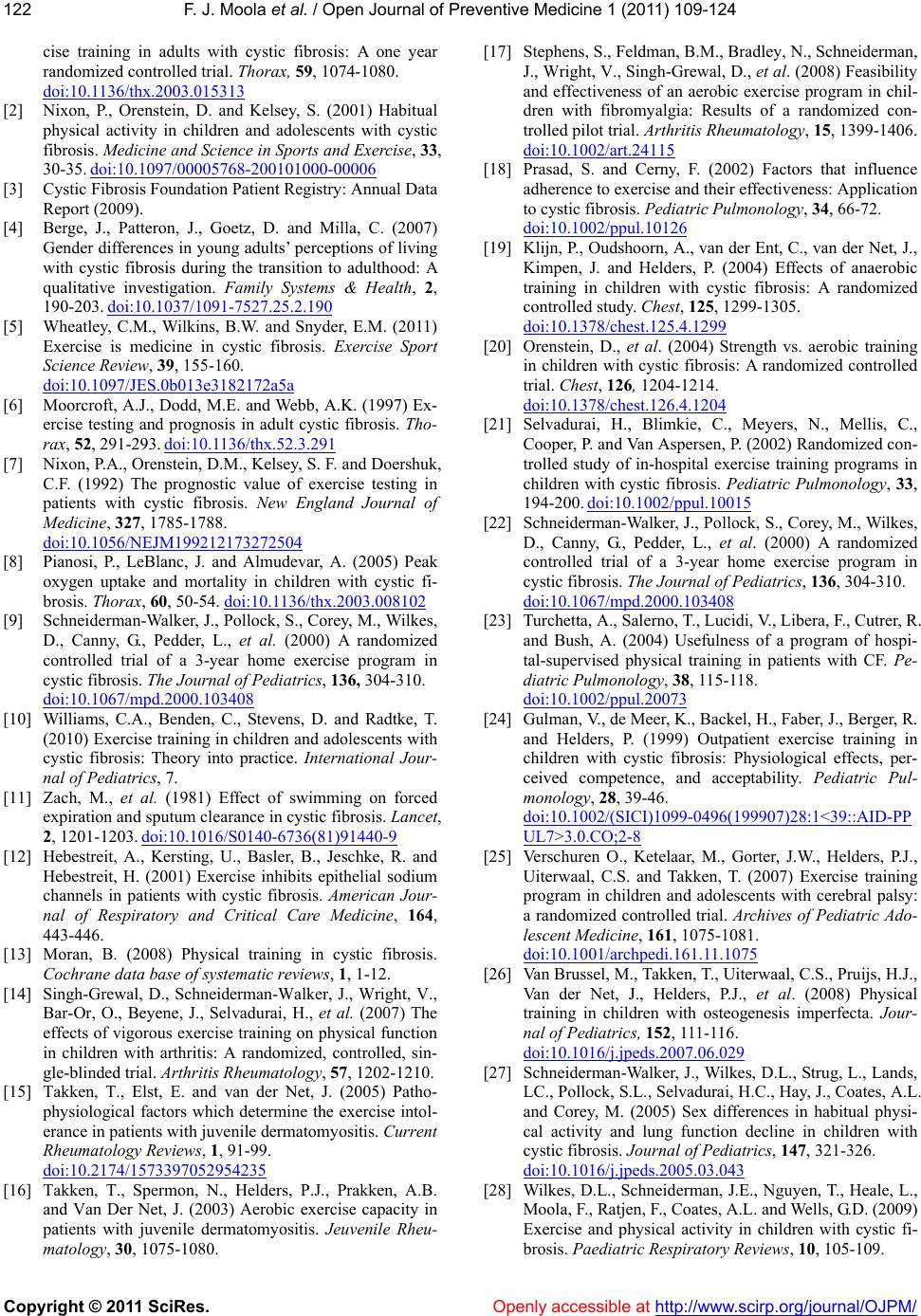

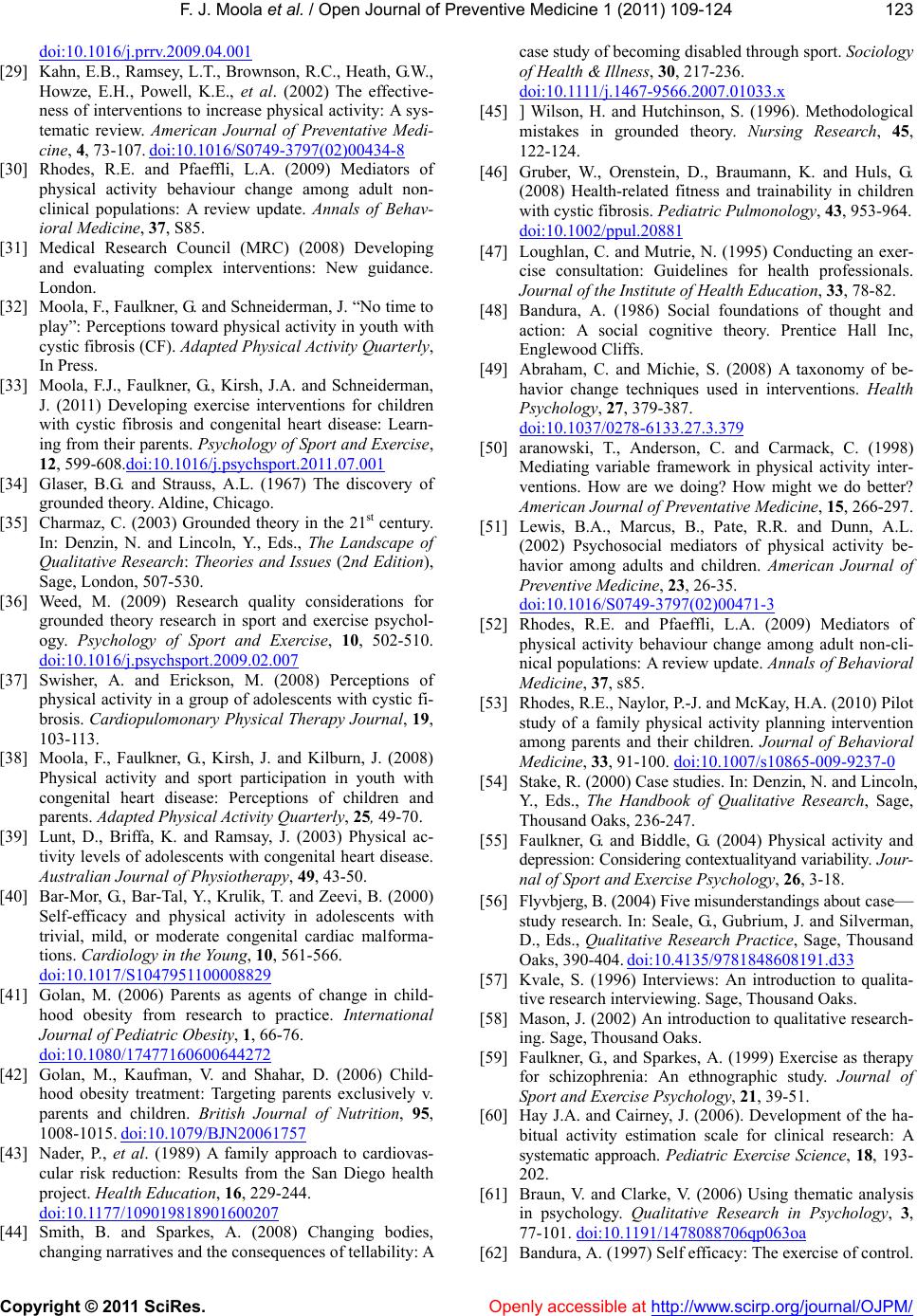

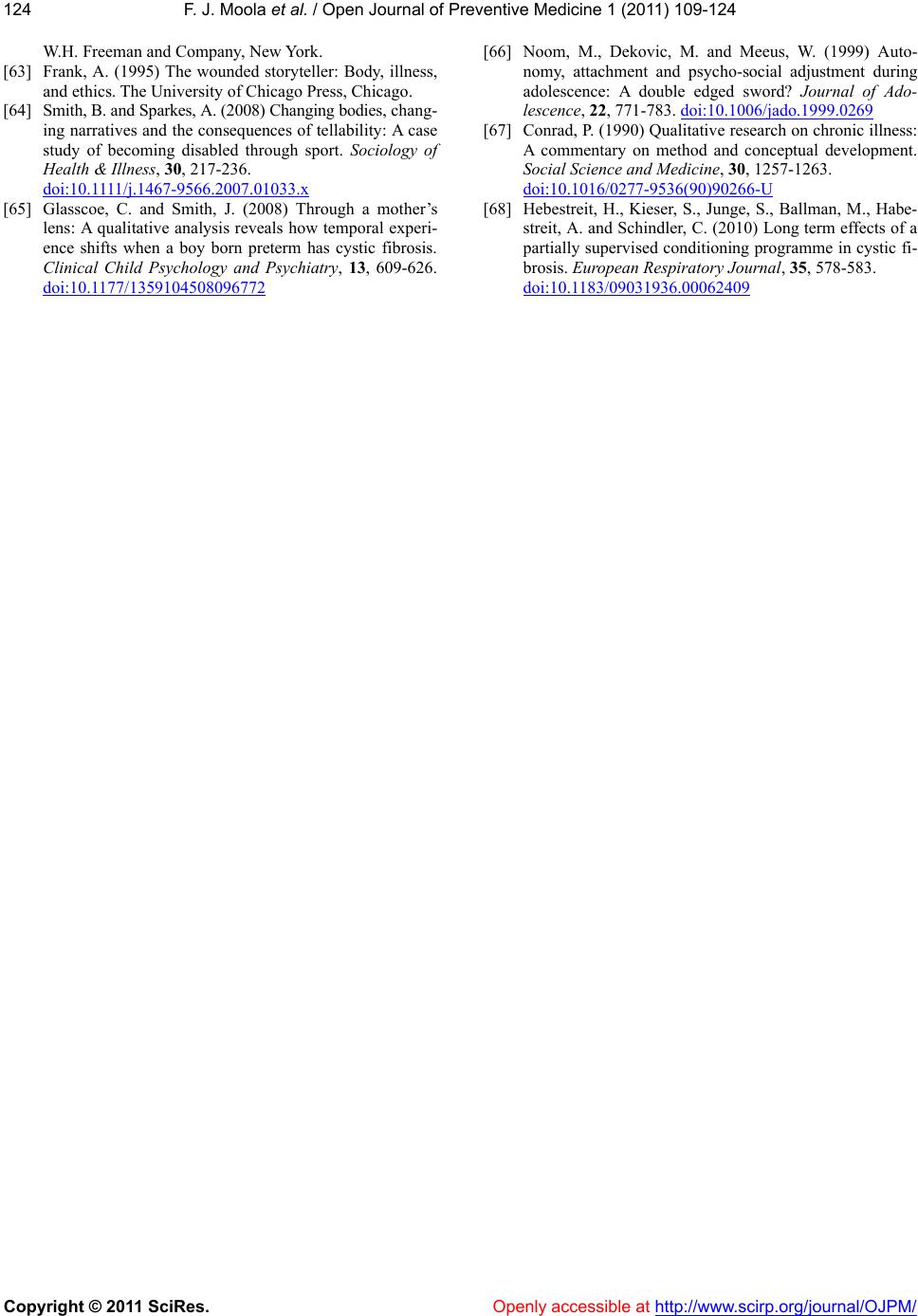

Vol.1, No.3, 109-124 (2011) doi:10.4236/ojpm.2011.13016 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ Open Journal of Preventive Medicine “CF chatters”: the development of a theoretically informed physical activity intervention for youth with cystic fibrosis Fiona Jasmine Moola1*, Guy Edward John Faulkner2, Jane Ellen Schneiderman3 1Simone de Beauvoir Institute, Concordia University; *Corresponding A uthor: fiona.moola@utoronto.ca 2Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences, The Univ e r s i t y of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; 3Department of Physiology and Experimental Medicine, Research Institute, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. Received 15 September 2011; revised 20 October 2011; accepted 31 October 2011. ABSTRACT Despite the benefits of physical activity for youth living with cystic fibrosis (CF), the majority of patients are insufficiently active to meet physical activity recommendations. Existing physical acti- vity interventions are atheoretical and tend to prescribe standardized exercise regimes which are often not appealing fo r children and compro- mise long term adherence. Following recent calls for counselling based physical activity approa- ches in the CF population, this study describes the development of a theoretically informed, pa- rent-mediated, behavioural counselling interven- tion for CF youth―“CF Chatters”. We first a) de- scribe the development of a grounded theory of physical activity in youth with CF; b) explain how this theory informed the development and im- plementation of the CF Chatters program and c) reflect on the findings of our pilot intervention using a case study research design. CF Chatters participants demonstrated self reported increa- ses in physical activity and quality of life. While further development and more robust objective measures are needed to extend this investigative pilot work, our findin gs suggest that beha vioural counselling is an effective modality for enhanc- ing physical activity participation and quality of life in this life limited group of children and youth. Keywords: Cystic Fibrosis; Physical Activity; Children and Youth; Behavioural Interve ntion Development; Qualitative Research; Ca regivers 1. INTRODUCTION Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a fatal, autosomal recessive genetic disease that affects approximately 1/2500 people. Although CF is a multi-system condition that affects the digestive and musculoskeletal systems, the primary cause of death is respiratory failure [1,2]. Advances in medicine are particularly evident in the case of CF and the prognosis has dramatically improved. For the first time in the history of CF care, the number of adults with CF exceeds that of children, and the average life expec- tancy is more than 38 years [3]. Physical therapy, aerosol inhalers, nutritional supplementation, pharmacology, and, in some cases, lung transplantation, comprise the back- bone of CF treatment today. The objective of these pal- liative treatments is to attenuate lung function decline over time. An improved prognosis and life expectancy, however, has done little to alleviate the lingering psycho-social burden of disease in CF [4]. Clinicians now encounter a group of youth who are living longer lives; albeit, lives that are compromised by significant morbidity and im- paired quality of life. Patients with CF display high rates of morbidity and reduced psych o-social health. They are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, body im- age concerns, occupational restrictions, reduced quality of life, and poor treatment adherence [4]. In addition to considering the physical health of this population, it is important to develop interventions that enhance optimal functioning and qua lity of life. 1.1. The Role of Physical Activity in CF There is growing attention to the role exercise might play in attenuating the progression of pulmonary disease [5]. Higher physical activity levels and peak VO2 are positively related to survival in CF [6,7]. This associa- tion between aerobic fitness and survival is perhaps the most compelling rationale for the incorporation of an active lifestyle into the care of CF patients. There may be a positive effect from exercise on pulmonary function  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 110 by increasing aerobic and anaerobic capacity [8] and strengthening ventilatory muscles, with chronic exercise programs being associated with a slower rate of pulmo- nary function decline [9]. Furthermore, exercise stimu- lates mucus clearance [10]; by blocking the sodium channels of the respiratory epithelium, exercise also con- tributes to lower mucus viscosity and the easing of mu- cus clearance [11,12]. Conversely, inactivity in patients with CF may worsen lung disease and compromise participation in activities of daily living [13]. Chronically ill children, including those with CF, may suffer from exercise intolerance- these children have poor fitness, spend less time exer- cising, and are often deconditioned [14,15]. Many chro- nic illnesses place a greater energy demand on children– walking and other tasks may require more energy ex- penditure [15-17]—which leads to fatigue, lower physi- cal function, and ultimately lower social participation and reduced quality of life. Accordingly, most youth with CF are less active than healthy age-matched peers and activity levels diminish further during adolescence [18]. However, there are four randomized control trials examining the physical and functional benefits associ- ated with exercise training for CF children and these intervention studies demonstrate that aerobic and st reng th training can significantly improve pulmonary function, aerobic fitness, and strength [19-22]. From an intervention perspective, there are two cen- tral limitations in this research field. First, existing re- search adopts a conventional exercise training approach. Although hospital-based programs facilitate a high de- gree of patient supervision and monitoring [23], such programs may lack sensitivity to children’s local envi- ronments, interests, and contexts and may not be inher- ently enjoyable and appealing for children. In addition, they are cost and resource intensive, and, upon termina- tion of the program, they invariably encounter difficul- ties with sustainability [22,23]. The issue of sustainabil- ity deserves considerable attention, given that a fre- quently encountered problem for chronically ill patients is the deconditioning that occurs after the cessation of the structured exercise training program [24,25]. A com- plementary yet arguably more realistic approach is to encourage increases in physical activity by integrating opportunities for physical activity into daily routines. There is some evidence that habitual physical activity is positively associated with lung function (FEV1) at least in girls with CF and that FEV1 is associated with long-term survival in CF [26]. Interventions aimed at increasing ha- bitual physical activity may be more successful with re- spect to long term compliance compared to conventional exercise training interventions [27]. However, we are not aware of any interventions that hav e atte mp ted to increa se habitual physical activity among children with CF and examined whether increased physical activity is associ- ated with improved quality of life. Second, in reviewing the existing research, it is clear that there is no explicit theoretical approach informing the development and delivery of the described exercise intervention. That is, it is not clear how investigators intend to change th e behaviour of their p articipants either in terms of short term adherence to a program or longer term maintenance of exercise behaviour. Theory-based physical activity interventions in the general adult popu- lation have been shown to be more effective at increasing activity than atheoretical interventions [28]. Theory also provides a roadmap to help clinicians promote behaviour change more efficiently. At the least, teaching the behav- ioural self regulation skills necessary for families to in- dependently regulate physical activity behaviours and to adhere to physical activity over time is necessary [29]. To our knowledge, existing research has not explicitly en- gaged in this process. The development and application of a theoretical framework grounded in the realities of living with a chronic disease, such as CF, is necessary. Before developing large scale interventions, the Medical Research Council [30] framework encourages researchers to engage in preliminary, developmental work with potential users, to ensure that interventions address areas of concern that are relevant to users. Methodological research suggests that this vital pre- paratory work is often overlooked [30]. Thus, this paper has three objectives. First, given the atheoretical nature of the literature, we describe the development of a grounded theory of physical activity for CF youth. Sec- ond, w her e grou nded th eor ies are rarely applied, we then describe the application of this theory in informing the development of a behavioural counselling program for CF youth known as “CF Chatters”. Finally, d rawing on a case study approach, we describe and reflect on a pilot evaluation of the pr o gram. 2. METHODS: OVERVIEW We have conducted qualitative research with CF chil- dren and their parents to identify disease specific barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation [31,32]. This developmental work has allowed us to identify key barriers and facilitators of physical activity in this pop u- lation, and develop a grounded theory of physical activ- ity participation in CF you th. Using a case-study design, we then piloted an intervention based on a self-regula- tory approach to behaviour change that engaged both youth and their primary caregivers. These steps are now described. 2.1. Developing a Grounded Theory We conducted two qualitative studies that sought to  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 111 examine how CF youth and their parents perceive and experience physical activity [31,32]. Informed by the grounded theory qualitative research tradition, we then conducted an in-depth qualitative analysis—or crystalli- zation—of the findings from these two studies to create a theory of physical activity in CF. Grounded th eory is a total qualitative research design that encompasses both methodology–or how knowledge about the social world should be produced, as well as methods or tools for the collection of data in the social world. Although grounded theory is a hotly debated and contentious research design, and reflects great evolution over time, it is a theory driven qualitative tradition that facilitates greater comprehen- sion of a particular groups’ social experience in natural- istic settings. As in the case of physical activity for youth with CF, grounded theory is particularly useful for the investigation of unknown or poorly understood social experiences as they unfold in the social world [33-35]. While a detailed discu ssion about th e grounded theory research tradition is beyond the scope of the present study, a few points related to this research tradition are important to discuss. Sp ecifically, ground ed theory relies on a process of abduction for the production of know- ledge. Researchers may be theoretically sensitized to a particular area; having read literature on physical activ- ity and CF, they do not arrive to the research field as a tabula rasa. However, despite being theoretically sensi- tized by the literature, the process is data driven. Thus, the analytic process remains grounded and embedded within the data itself. In this regard, novel information arises in and through the data and all interpretations are data driven and empirically supported [35]. Additionally, it is also critical to discuss the episte- mological assumptions that lie at the heart of grounded theory. Although grounded theory has changed from a largely post positivist articulation, in this study, we em- ploy Charmaz’s social constructivist version of grounded theory. We acknowledge that the data analysis process is always an interpretive act, and, rather than discovering or “excavating” true facts, the findings are co-created interpretations that arise at the interface between the researchers and the participants. Thus, we concur with Charmaz’s reflection on the data collection process when she states that “data do not provide a window on reality. Rather, the discovered reality arises from the interactive process and its temporal, cultural, and structural con- texts” [34,35]. In developing our grounded theory of physical activity in CF, we were guided by Weed’s eight principles for “full fat” grounded theory. Seeking to avoid methodo- logical policing and fundamentalism, these criterion are not hard and fast rules. Rather, Weed’s grounded theory criterion ensure that researchers employ all aspects of the GT tradition, rather than selectively “handpick.” Adhering to these criteria enhances the internal micro level consistency of the study itself, as well as macro level consistency to larger bodies of knowledge [35]. Following Weed [35], first, we adopted an iterative stance toward the data collection and analysis process. Thus, data collection and analysis were not divorced from one another, and, rather, the emerging data analysis guided the data collection process. Furthermore, we em- ployed theoretical sampling. Thus, the findings that emerged during the data analysis process were further “fleshed out,” expanded, and explored during data col- lection. Thirdly, we strov e to attain theoretical sensitivity. As such, while the researchers’ bias invariably influ- ences the analysis process, we strove to be cognizant of the assumptions that drive the investigation and re- mained open to new and emergent lines of inquiry. Fourth, the constant comparative method guided the data analysis process. While we did not adopt open, axial, and selective coding, a) the 30 transcribed interviews were thoroughly read multiple times both individually and across the data corpus, b) coded for relevant units of meaning that relate to physical activity in CF youth, c) sorted and collated into named conceptual themes, d) collapsed and refined into higher order concepts, and e) searched for the inter-relationship between themes. To aid the analytic process, we used memos–or notes-to assist with the coding of the data. Sixth, by being aware of how our personal biographies influence the research process itself, we adopted a self reflexive stance. Sev- enth, in both the ch ildren’s and p arents study, the collec- tion of fresh data failed to render new theoretical in- sights or to expand our concepts. In this regard, the data was theo retically saturated . Eighth, while d ifferent crite- rion are used to ensure the micro-level internal consis- tency and quality of a qualitative analysis, the princip les of fit, work, relevance, and modifiability guided our judgments about research quality. In this regard, the resulting theory accurately fits and describes the data. Furthermore, the theory offers explanations to problems that are observed within the research context, such as parental stress, and reflects the concerns that are relevant to the participants. Finally, the theory is modifiable and open to further extensions and insights that may be of- fered in the future about the data. Finally, we “thought theoretically” from the beginning of the investigation and strove to develop a parsimonious substantive grounded theory of this particular social experience [35]. In sum- mary, we employed the grounded theory qualitative re- search tradition to conduct an in-depth analysis of the transcribed interview data from our children’s and par- ents’ study [31,32], and, in doin g so, developed an in itial conceptual framework that describes and explains how  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 112 CF youth and their parents experience physical activity. Our theory is described and illustrated within th e context of the literature (see Figure 1). For CF youth and parents, the burden of disease was described as the most noxious barrier toward physical activity. By making participants feel unwell, symptoms such as breathlessness, fatigue, and dizziness led youth to avoid physical activity. The detrimental impact of disease symptoms on the ability to be active has been reported by other CF youth [31,36], as well as youth with chronic diseases more broadly. Interventions must remain sensitive to youths’ real and perceived symptoms and work toward the minimization of disease related burden. Furthermore, CF youth and parents reported low value toward physical activity. Within the context of feeling unwell–and lacking mastery experiences that confirmed feelings of success–youth gradually reparti- tioned their energy away from physical activity and did not define it as an important or valuable pursuit. Physical activity value shifts have been reported in youth with other chronic diseases [37,38], suggesting that such value changes may serve a self protective function that prevents further damage to self esteem losses. As such, physical activity interventions should work toward en- hancing the value that youth ascribe toward physical activity itself. Parents stated that low self-efficacy for physical activity-or lacking experiences of success–was a detrimental barrier that led their children to avoid physical activity. Th e social environments in which chil- dren undertook physical activity, such as physical educa- tion settings or community physical activity groups, were often not self-efficacy supportive and were charac- terized by experiences of exclusion and hostility from healthy, able body peers. Youth often encountered bul- lying and discrimination on account of their non-norma- tive embodiments. Low self-efficacy for physical activ- ity is well documented [37,39], and appears to be a ge- neric experience that characterizes youth with chronic diseases more broadly. Interventions for this population should work toward self efficacy enhancement for physical activity. CF youth underscored the importance of parental support for physical activity. Youth that lacked parental physical activity support lamented the absence of this important instrumental and emotional function, and wished that th eir par ents would eng age in physical activ- ity with them. Regardless of whether they were positive or negative role models, parents also discussed the im- portance of parental role modeling of physical activity behaviours. While previous interventions have not en- gaged parents as important sources of social and emo- tional support for physical activity– and critical role models–literature from the field of pediatric obesity un- derscores parents’ important role modeling function. In particular, due to the facts that a) parents are “gatekeep- ers” to health behaviour change who either facilitate or hinder physical activity, b) individual behaviours are strongly influenced by contextual, familial, and envi- ronmental factors, c) social modeling and observation is critical to the development of healthy behaviours in children, and d) members of the same family tend to be genetically and behaviourally similar, there are compel- ling rationales for the inclusion of parents in physical activity interventions [40-42]. Additionally, youth ado- pted different illness narratives to articulate their ex- perience of living with CF. While some youth reported a sense of hope and resilience in which physical activity was employed as “proof” of the ability to conquer CF, others expressed an overwhelming sense of despair and hopelessness as a result of CF. Interestingly, youths’ ill- ness perspective influenced physical activity perceptions, with more hopeful youth ad opting more positive evalua- tions of physical activity. While the relationship between illness narratives and physical activity perceptions re- quires future investigation, sociology of health and ill- ness scholars have emphasized the importance of narra- tive and story telling in making meaning out of experi- ence, and facilitating a sense of coherence [43]. Inter- ventions should consider the relationship between youths’ illness ou tlook and attitud e, and work toward the facilitation of more positive ways of storying one’s ill- ness experi ence. Finally, the higher order concept of “Living on the Edge of Health and Illness” within our grounded theory refers to the precarious and fragile grasp that these chil- dren and parents have on health, and the tremendous effort they demonstrate to prevent the encroachment of illness into their everyday lives. Children and parents live with a constant sense of stress and impending dan- ger, and sources of stress include child non-adherence to treatment and living with a life shortening disease. In particular, given the life limiting nature of the disease, and the time consuming nature of treatment, CF patients and parents negotiate significant temporal losses, mak- ing them more sensitive to temporal stress and proper time use. “Living on the Edge of Health and Illness” comprises the broader context in which these families negotiate physical activity and influences the perceptions they adopt toward physical activity. It is critical for in- terventionists to remain sensitive and empathetic to the enduring sense of stress that these families negotiate, and understand that physical activity experiences are inseparable fr o m health. Grounded theories are often not applied and this is a significant limitation associated with the gr ounded theory approach [44]. In the following section, we describe the process by which our grounded theory—and each of the  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 113 Disease Burden Negative Activity Perceptions Positive Activity Perceptions Illness Narrative: Despair Low Value Parental Support: Lacking Illness Narrative: Hope Parental Support Low Self Efficacy “Livin g on the Ed g e of Health and Il ln es s: ” Fa mily Fragility, Uncertainty, and Chao s Figure 1. Toward a grounded theory of physical activity in CF. main theoretical constructs from our th eory-were applied to develop, implement, and evaluate a behavioural coun- selling program known as CF Chatters. 2.2. CF Chatters–Intervention Development Based on this preceding work and the broader litera- ture on the determinants of physical activity in children and youth [45], we developed a six-week family medi- ated physical activity counselling program called “CF Chatters”. The name “CF Chatters” semantically plays on the informal, discussion based nature of the program. Since youth express negative views toward treatment, CF Chatters also demarcated the program as distinct from treatment. The content of the intervention was based upon and informed by our grounded theory which identified the disease-specific barriers and facilitators to physical activity. The first author delivered all of the intervention con- tent to the participants and a counselling based app roach was utilized to engage the participants in informal dis- cussions. We define counselling in this context as a per- son and family centred consultation approach to in- creasing physical activity [46]. Given the limitations associated with prescribing exercise training to children and the importance of autonomy and choice to health and wellbeing, the program was based on individual ac- tivity choices. Thus, while increased physical activity was encouraged for all the participants, the exercise counsellor supported participants’ autonomous decision making about enjoyable physical activities, and facili- tated participant physical activity choice. The program commenced with an initial assessment phase in which the program was explained and materials delivered. The program itself consisted of three, 90 minut e counselling sessions over the course of six weeks. The length of the programme was largely driven by pragmatic concerns. We sought to develop an intervention that was effective in increasing physical activity but cost-effective in terms of the time and resources required to deliver it, and the time burden on patients. Reminder and review Openly accessible at  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 114 phone calls were interspersed between each session, in which the researcher phoned the participants to discuss their progress and review barriers (see Figure 2). The session content was developed to address the cen- tral content areas from our grounded theory. For instance, workbook activities such as “My Wheel of Life” or “Where am I Going?” sought to identify and shift par- ticipants’ physical activity values from our theoretical model. Session one sought to educate participants about physical activity in CF and enhance value for physical activity (Time Two). Session two sought to facilitate bet- ter temporal management of physical activity (Time Three), and session three sought to reduce barriers to physical activity participation (Time Four). In this regard, the intervention content—which was incorporated into a working manual for the participants—or homework-was embedded within our grounded theory and served as a prompt for di scussi on (see Table 1). To assist in implementing the grounded theory, we were guided by Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory [47] with specific intervention components drawn from an existing taxonomy of behaviour change strategies de- signed to target common, hypothesized mediators of physical activity behaviour change (48,49]. These can be best characterized as facilitating behavioural self- regulation. Reviews of the literature on mediators of be- havior change position self-regulatory constructs (e.g., planning, contingency strategies, self-monitoring) as the most consistent agents of change [50,51]. In general, health behaviour change programmes that teach behav- ioural skills for self-management have been recom- mended because of their effectiveness in promoting physical activity (Kahn et al., 2002). As described by Rhodes and colleagues [52], the basis of these ap- proaches is that regulatory skills are required to link po- sitive intentions to subseq uent behaviour. These include, for example, the specifics of a behavioural plan (e.g., wh at, when, where, with who) and the problem so- lving and monitoring of action. Educational approaches on the benefits of physical activity for CF, and how to incorporate habitual physical activity into the day may help create positive attitudes and enhance self-efficacy. However, these approaches may not necessarily ensure positive intentions are translated into behaviour. There- fore, the intervention incorporated techniques such as goal setting, monitoring, recording, planning, and con- tingency planning. The goal of the intervention was to teach participants the behavioural skills required to in- dependently manage their own physical activity, and to promote enjoyable physical activity in youths’ local en- vironments. 2.3. CF Chatters―A Case Study Evaluation As “embedded case studies”, [53] the CF Chatters program was pilot tested with six CF patients and their caregivers to assess the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of the program. Case study research, which employs multiple methods, can be described as the in- depth study and investigation of a few lives in context. The case study approach is particularly useful for preli- minary intervention research in that it illuminates par- ticipants’ individual uptake and appraisal of a program [53-55]. 2.4. Participants After approval from the Research Ethics Board at the Hospital for Sick Children, the CF Chatters intervention was delivered between September and December, 2010. With the assistance of a clinical nurse facilitator and exercise physiologist, eligible case study participants for the CF Chatters pilot intervention were identified and contacted using the clinic data base. After the study was explained and informed and written consent obtained, Assessment: HAES Time 1 Session One: Education/ Values Time 2 Session Two: Planning an d Environments Time 3 Session Three: Barriers HAES/ interview Time 4 Phone call Phone call Phone call Week One ____________________________________ __________________________________ _________________________ Week Six Figure 2. CF chatters program .  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 115 Table 1. CF chatters workbook activities, theoretical constructs, and behaviour change strategy. CF Chatters Session Work Book Activities Theoretical Construct Behaviour Change Strat- egy or Process One -What does PA mean to me? -How does PA make me feel? -What are some examples of PA’s that I could engage in? -What are some examples of PA’s that I would really enjoy engaging in? -PA and the lungs -What is CF? -How does PA affect CF? -The benefits of PA for CF -The benefits of PA for overall health -Other physical benefits of PA -Psycho-social benefits of PA -PA is safe Physical Activity Knowl- edge -Psycho-Education -Cognitive behavioural skills training (CBT) -Goal setting One -What do I value in life? -Where did I come from an d where am I going? -What are the advantages and disadvantages of becoming active? Value Toward Physical Activity -Psycho-Education -CBT -Behavioural cost and re- ward -Goal setting Two -What does time mean to me? How do I want to use my time? -Is treatment time consuming? -Do I have enough time for PA? -Planning PA -PA Calendar activity -PA action plan -PA coping plan Temporal Loses -Planning and Scheduling -Goal setting -Monitoring and recording -Psycho-education -CBT Two -My neighbourhood and community -My PA environments -How can I better engage in PA in the environment? -Google earth map activity Understanding Physical Activity Environments -Psycho-Education -CBT -Mapping exercises Three -How do you feel when you are ill? -What happens to your PA when you are ill? -What happens to your PA when you are ill? -Staying active du ri n g il l n e s s -Falling off the wagon -What are high risk PA situations? -PA relapse preventi on plan -Obtaining social support -My PA barriers -Developing strategies to deal with barriers Disease Burden Goal setting Behavioural Cost and Re- ward Psycho Education CBT All sessions -The wheel of life -Caregiver health -Low self efficacy for physical activity -Parental support and role modelling -Stress Psycho-Education and CBT PA = Physical activity. eight participants enrolled in the CF Chatters program, including three parent-child dyads (N = 6) and two ado- lescent participants (N = 2). One parent-child dyad dropped out over the course of the investigation as a result of a CF related exacerbation, reflecting a study retention rate of 80%. The remaining four child partici- pants consisted of three girls and one boy and the mean age was 14. Disease severity of the child participants was measured by forced expiratory volume in one sec- ond (FEV1) and ranged from 70% to 85%, reflecting mild to moderate lung disease. Three of the four child participants had been hospitalized on numerous occa- sions. Additionally, one male and one female parent par- ticipated; their mean age was 44 years. Participants were from the Greater Toronto Area and surrounding region and reflected a range of ethnicities and socio-economic brackets. 2.5. Data Collection Methods Case study research is composed of multiple methods and these are briefly described. Semi structured inter- views were employed in order to explore participants’ experiences of the program. Although a semi-structured interview guide was developed by the researcher to un- derstand their experience of the intervention, the par- ticipants’ responses dr ove fur ther lines of inqu iry and the  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 116 interview proceeded in terms of a recursive conversation. Thus, the semi-structured interview provided a useful lens to understand participants’ experiences of CF and physical activity and their perceptions of the program. These interviews were digitally taped and transcribed verbatim [56,57]. A detailed field note journal was used throughout the study to record, describe, and characterize participants’ responses to the CF Chatter’s program, institutional ob- servations, personal reflections, and novel insigh ts about the program. Over 150 pages of field work data was col- lected over the course of the CF Chatters program and observations were recorded before, during, and after each session. The field work data further corroborated the interviews and provided an excellent forum to un- derstand the unique facets of participants’ lives as well as their response to the program [58]. The Habitual Activity Estimation Scale (HAES) was employed as a self report measure of physical activity to track changes in physical activity as a result of the Chatters program [59] Th e HAES is a reliable an d valid tool that was developed by pediatric researchers to as- sess level of habitual physical activity in children with chronic diseases. 2.6. Data Analysis In order to analyze the case studies, first, a thematic analysis of the transcribed interview data and field diary data was generated [60]. Interview question responses, such as the program impact on physical activity and quality of life, were coded, named, and grouped into broader themes. Novel responses that were not a com- ponent of the interview guide, such as how the program facilitated “tough talks” or the psychological benefits of the program, were also named, coded, and grouped into themes. This thematic analysis of the transcribed data allowed us to understand participants overall perception s toward the CF Chatters intervention. The HAES esti- mates the percentage of time that children and parents in this case, spend being a) inactive b) somewhat inactive c) somewhat active or d) active. Data was collected based on one typical weekday or weekend day and entered into a spreadsheet to calculate the percen tage of th e day sp ent in each of the four categories of activity. These values were compared from baseline to week six. 3. RESULTS Eight participants enrolled in the CF Chatters program. However, after the first session, one parent-child dyad (two participants) dropped out due to a CF related exac- erbation. The remaining six participants (two parent- child dyads and two adolescent participants) attended all sessions, reflecting 100% attendance. The participants also completed all of the workbook or homework activi- ties prior to each session as instructed, and actively par- ticipated in weekly phone call sessions, reflecting good intervention compliance. The participants described the program as easy, convenient, relevant to their physical activity concerns and enjoyable, suggesting that the in- tervention was feasible and acceptable. Physical Activity Self reported physical activity levels measured by the HAES and as described in qualitative interviews in- creased among the majority of the participants over the course of the investigation (see Table 2). In particular, percentage daily physical activity in- creased from pre to post test, as well as hours of active category physical activity. For instance, during her qualitative interview, 16 year old Layla explained that over the course of the program, she changed from a state of inactivity to engaging in three, 20 minute sessions of basketball/week as well as walking to school on most days of the week: My activity did change. Now, whenever I am sitting around and doing nothing, I am starting to think that “maybe I could go aside and run around or play basketball or soccer.” It gets you active and it also helps your body. In addition to self-reported increases in physical activ- ity, there were seven themes that captured the benefits of the program for the participants. Increases in Physical-Related Quality of Life: The participants consistently stated that the CF Chatters pro- gram facilitated enhanced quality of life in the physical- domain; engaging in more physical activity led to con- Table 2. Changes in physical activity as a result of the chatters intervention. Name Age Pre to Post Test Change, % Total Daily Activity Pre to Post Test Change in Hours of Daily PA Pre to Post Test Change, Active Category Outcome Layla 16 7.9% 1.89 hours 3.3% 0.8 hours Increase daily PA Chase 17 6.6% 1.58 hours 1.9% 0.46 hours Increase daily PA Emily 11 18.5% 4.44 hours 24.7% 5.93 hours Increase daily PA Zoe 12 –7.6% –1.83 hours 1.1% 0.25hours Decrease daily PA P A = physical activity.  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 117 sequent improvements in how they felt about their phy- sical health and functioning. Since the program bettered youths’ self reported endurance and ability to partake in activities of daily living and peer group activity, it im- proved their physical well-being and reduced exclusion from physical tasks that contribute toward poor percep- tions of physical health. For instance, one 17 years old participant, Chase, explained that the program enhanced his running ability. Since he is less likely to be excluded from physical activities with his friends and feel “down” about himself, his physical quality of life greatly im- proved. Reflecting on the meaning of quality of life, Chase stated that: My quality of life altered a little. With the running- wanting to run more and then actually changing to run more-that is only going to help. So, my quality of life did raise a little. It helped the physical part of quality of life, with endurance and being able to run more. Endur- ance comes up all of the time with CF. It does not have to be running. It could be who knows- whatever kind of activity. Endurance and stamina are important. I can avoid situations that bring me down, because I am not able to do someth ing. I will be able to avo id those things with better endurance and have a better quality of life. Enhanced Physical Activity Knowledge: The program also enhanced education and awareness about the bene- fits of physical activity for CF. Although participants had good knowledge about cystic fibrosis, the program fa- cilitated specific increases in knowledge about the rela- tionship between physical activity participation and re- duced disease symptoms. Additionally, participants also learned about the psychological benefits of physical ac- tivity: But I learned that physical activity help s your psycho- logical-and your think ing and stuff and your lungs. And, I learned that I never knew that it could help that much, but it can (Emily, age 11). For participants with lower levels of baseline physical activity–that is, Layla, Zoe, and Gretchen-psycho-edu- cation, or educating participants about the benefits of physical activity for CF and identifying, modifying, and challenging thought misconceptions, was the most effec- tive technique. For instance, Layla was misinformed about physical activity and falsely believed that it was injurious to health. Indeed, while increased sputum clea- rance and coughing during activity is beneficial for CF patients, this may frighten or confuse misinformed youth, leading them to consider physical activity as injurious. Similarly, Zoe and Gretchen were not aware of just how important physical activity is for lung health in CF, and such psycho-educational discussions facilitated better understanding. Enhanced Self Knowledge: Additionally, the program enhanced knowledge “about the self,” equipping par- ticipants with a greater understanding of who they are as unique individuals. In this regard, participants suggested that the program facilitated a greater degree of self re- flexivity, awareness, and insight into personal barriers to physical activity and individual coping and resiliency: Yes, like the questions in the book make you think about things and the kind of person that you are. Well, the program has made me think more about myself, and to think about what I need to do to stay healthy and to have a good life (Layla, age 16) Value Shifts: The program also appeared to facilitate important value shifts in which participants came to as- cribe greater value to the importance of physical activity within the context of their daily lives. Participants dis- cussed how the program facilitated an understanding of why physical activity should be a priority and contrib- uted toward a different perspective on the importance of physical activity: The program gave me a different perspective. To say, “What can we do to change things and to make things a priority in all of our lives and not just their lives?” That dynamic in the family does need to shift to be more ac- tive. To becoming more of a social aspect, rather than a “oh, we have to do this, aspect …What I got more out of it, was the change in attitude and the knowledge that there was-that we needed to have a different perspective to get active-that is what I will come away with (Gret- chen, parent). Reduced Disease Barriers: The program assisted youth in identifying and dealing with disease related barriers to physical activity. Participants devised novel coping strategies to deal with the negative impact of di- sease symptoms on physical activity–such as creating a relapse prevention plan–thereby arguably attenuating perceived helplessness related to inactivity. For instance, rather than remaining completely inactive when hospi- talized, Emily and her parent, Erik, suggested that they could reduce the negative impact of the disease on physical activity by taking brief walks in the hospital u- nit or on the hosp ital grounds outdoor s. They also appre- ciated a proactive approach to thinking about physical activity barrier reduction: And even what we talked about today with the barri- ers ... lik e “here a re the barr iers and how c an you plan to overcome the barriers?” You start to think about it before it happens. And I think that is a very good thing because then you are not caught off guard, when it does happen. I think that it was important to talk about, so, again, you can plan it out ahead of time. Get used to think ing about it, ahead of time. “Like, Emily is going into the hospital. What can I do? We can walk up the stairs, right. We can walk around” (Erik, father).  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 118 Accordingly, contingency planning–or planning what one will do if original efforts and intentions to be active are not successful–was the most effective strategy for those participants that were experiencing greater disease symptoms and burden, such as Layla, Emily, and Erik. For instance, Emily and Erik proposed a contingency plan that consisted of attending at least one dance class a week during times of illness, rather than skipping class altogether, or assisting with household chores at home rather than remaining sedentary on the basement couch. Tough Talks The participants suggested that the program offered important psychological benefits by facilitating “tough talks” that would have been difficult to have in the ab- sence of a counsellor. For instance, participants valued the opportunity to discuss the social and psychological impact of living with CF with a counsellor in a safe and supportive setting. One mother in particular commented on the absence of psychology in the care of patients with CF as a limitation of clinical practice, and the impor- tance of adopting psychological approaches to manage the psycho-social impact of caring for a CF child: I mean, we get familiar with the medical staff. We know the respiratory therapist, we know the nutritionist, we know the nurses, and we know the doctors. But, we do not know the psychological side of things. That is because we only see psychology unless we ask for that. If you do not have a significant issue, then, you will just coast along, as though it is just a part of your lif e. This is a significant issue within our lives. Not just from the kids perspective, but from our perspective as well. So, having the opportunity to talk through some of those issues-even if you say “everything is fine” or, rather “maybe we do need to talk about that, a little more” … As a parent, we tend not to have the time to have these conversations with our children. We tend to be focused on our day to day existence. We do not have the time to have an in-depth conversation and we do not have the time to spend time together, with somebody leading the discussion. It has been excellent, from that perspective “Distinctly Different”. The participants described the pro- gram as distinctly different from routine clinical appo int- ments in that the sessions were non medical and discus- sion focused. They appreciated that the program did not include measures of respiratory function and other medical tests and that they were given the opportunity to engage in free and open discussions about their health, values, past, and personal beliefs. The participants ex- pressed favourable and positive perceptions toward the distinctly different nature of the CF Chatters program: I have never had to do this before. The program felt new. Interviewer: Did new feel good or bad? It felt good because I did not have to get any shots, and I did not have to do the breathing thing. So it was actually cool (Zoe, age 12). They are completely different appointments. When I come here, it is very structured and pretty much the same every time. I come here, do PFT’s, other tests, talk to doctors, give blood work, and then I am out. This feels different. It is like I am coming here for a meeting and it does not feel like I am here for a clinic visit. I like it. Generally, people like talking about themselves. I enjoy it. Same area of the hospital, but it feels different (Chase, age 17). The program appeared to enhance temporal reparti- tioning for physical activity in which participants dis- cussed the benefits of devoting more time toward physi- cal activity and increased their ability to plan for physi- cal activity in their daily lives. The program also en- hanced youths’ ecological acuity, or awareness of the places in their local environments that were physical ac- tivity supportive. For instance, using Google Earth maps and cognitive maps, participants identified places in the familial, school, community, and neighbourhood environ- ment that were health and physical activity supportive. In summary, the CF Chatters program was well at- tended and described as easy, convenient, relevant, and acceptable for the participants. The participants de- scribed the program as distinctly different from clinical care, and expressed favourable opinions toward the non medical, child centred, discussion oriented nature of the program. Although objective measures of physical activ- ity were not employed, the pr ogram was associated with increases in self-reported physical activity levels and quality of life in the physical domain. In addition to in- creased physical activity k nowledge, p lanning skills, and reduced physical activity barriers, the program appeared to afford therapeutic benefits to participants, reduce caregiver stress, and increase knowledge about the self and the environment. 4. DISCUSSION The findings from the CF Chatters pilot case study in- tervention can be interpreted within the context of our grounded theory of physical activity in CF and other relevant health behavior change theories. Specifically, the intervention assisted patients and parents in dimin- ishing barriers toward physical activity, most especially, disease related burdens. Described as the most noxious and unpleasant physical activity barrier, symptoms such as fatigue and breathlessness led youth to feel bad about themselves in physical activity, contributing toward ac- tivity avoidance. The negative impact of disease symp- toms on the ability to be physically active is well docu- mented in the literature-and the vicious, “chicken or egg” cycle of inactivity and escalating disease symptoms  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 119 that this may contribute toward [2]. By enhancing par- ticipants’ capacity to manage disease related barriers and identify and strategize ways of coping, the program di- minished disease burden and perceptions of disease re- lated helplessness. It is important to note that partici- pants found discussions about the burden of disease to be “extremely important” and “something that you have to talk about and should no t avoid”—wh ile also “sligh tly upsetting”. Thus, while participants suggested that dis- cussions about the burden of disease and its impact on physical activity were very important, such discussions must occur with the utmost sensitivity. Interventionists should follow youths’ lead with respect to how much and what aspects of their disease and its impact they want to discuss. Youth with CF and other chronically ill children are at risk of physical activity “value shifts [37,38]”. Within the context of feeling unwell and lacking self efficacy enhancing mastery experiences, they shift attention away from physical activity to protect self esteem, and de- scribe it as “not important”. As described by one parent [32], such progressive repartitioning of attention away from physical activity, can, over time, lead the child to develop a set of non-active interests and pursuits. The CF Chatters program appeared to facilitate slight value shifts for the participants over the course of the program. For previously active participants, the program served to reinforce the importance of activity to their broader value system. For less active participants, such as Layla, the program fostered broader discussions about what would need to change in her life for physical activity to become more valuable. In this regard, it appears that th e CF Chatters program may assist youth in better identi- fying and discussing the importance of physical activity to their broader value system. Future interventionists should work with youth to enha nce the value and impor- tance ascribed to this construct. Low self efficacy for physical activity among children with chronic diseases is perhaps one of the most well documented barriers toward physical activity. Often ex- cluded from same age peer group activity, these children lack mastery experiences in physical activity and often report negative experiences that compound self efficacy losses, such as bullying and demoralization on account of their non-normative embodiments [37]. Where good physical health, verbal persuasion and encouragement, mastery experiences, and vicarious learning are critical to the development of self efficacy [61], these youth are often deprived of the critical antecedents to healthy self efficacy formation. Although self efficacy was not a central chapter in our manual or a component of our in- terview guide, the CF Chatters program was broadly self efficacy supportive. By providing constant praise, en- couragement, and positive reinforcement for goal at- tainment, we sought to enhance children’s physical ac- tivity self efficacy throughout the program. Participants either displayed enhanced physical activity self efficacy, or, rather, the ability to identify situations and contexts that were self efficacy enhancing. For instance, through discussions and counselling, Chase recognized that he does not “suck at all sports”. In contrast, he recognized that while swimming and sprinting exasperate disease symptoms and make him feel badly about himself, ac- tivities such as cycling are self efficacy enhancing. In this regard, the program facilitated a more contextual conceptualization of self efficacy, rather than a static view of this construct. It appears that CF Chatters is self efficacy enhancing and future interventionists should continue to work toward buffering youths’ fragile physi- cal activity self efficacy. While it is beyond the scope of the current paper, the attitudes that youth adopted toward their illness–and illness narratives—was a very important theoretical con- struct that served to demarcate and differentiate the case study participants in this pilot study. The participants who displayed narratives of hope, optimism, and resil- ience–or what Arthur Frank [62] terms the “overcoming, restitution narrative”—reported fewer barriers toward physical activity and greater interest in adopting a physically active lifestyle. For instance, despite the fatal nature of CF, Emily, Chase, and Zoe discussed the im- portance of undertaking health behaviours that would slow the progression of the disease over time, such as engaging in physiotherapy, staying active, and eating well. Evidence on the benefits only confirmed their de- sire to be active, and they were eager to reap the health related benefits. In stark contrast, case patient Layla de- scribed a “chaotic” illness narrative [62], emphasizing her sense of futility, hopelessness, and depression. Layla often engaged in self sabotaging behaviours; since CF is ultimately fatal, she often did not see the point in treat- ing her illness and engaged in treatment non-adherence. It is important to note that despite her negative disease outlook, Layla did display increases in physical activity behaviour and physical quality of life that exceeded those of other participants in the program. However, it was more challenging to engage Layla in the program and encourage her to be active, and her all encompassing negative world view was a difficult mindset to engage with. While all other participants maintained physical activity after the termination of the program, Layla quickly resumed her previously inactive state and “silent treatment” mode of communicating with adults. It is important for future interventions to take stock of the ways in which the illness narratives that patients con- struct influence not only their understanding and coping  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 120 with illness [63], but also, their affinity and interest in physical activity. Interventionists should listen and hear [63] youths’ illness narratives, and work toward devel- oping more positive ways of storying their health and illness experiences. Finally, the findings from this study further extend and complicate our original theoretical construct of re- duced time for physical activity, suggesting that greater theoretical and methodological attention is required. Gi- ven the life shorten ing nature of the disease and the time consuming nature of treatment, participants in previous studies stated that they have “no time to play” [31]. Sur- prisingly, in the current intervention, all participants de- scribed the program as a worthwhile time investment that should be longer in duration. It is not clear if, with counselling, the program facilitated temporal repartion- ing for the participants in which they came to desire spending more time engaged in activities that were per- ceived to be valuable. Alternatively, CF patients may be “masters of their time” who do not waste time and more carefully negotiate their temporal outputs. In any case, the CF Chatters program was not regarded as wasteful of time and was a worthwhile temporal investment. This also suggests that the intervention could be developed, perhaps with top-up sessions to reinforce behavioral skills training without overburdening participants. Al- though the literature has repeatedly underscored the ways in which the body, self, and relationships are pro- foundly changed through CF and the illness experience [64], it is critical that more research on CF youths’ tem- poral negotiations-an d the impact on physical activ ity-be conducted. In this regard, our theory of physical activity in CF served as a useful template fo r the interpretation of study findin gs. Given the multiple component and multiple behaviour nature of complex interventions, the Medical Research Council [30] encourages researchers to undertake early developmental and feasibility work to explore potential users intervention needs and interests, and relevant con- textual issues. Furthermore, before larger scale, cost in- tensive research programs are undertaken [30], exploring the feasibility and likelihood of intervention work is strongly advocated. Although RCT’s serve as the “gold standard” of research based evidence, there are situations that impair their feasibility and in which common sense must guide best practice. Early developmental work to explore issues of feasibility assists researchers in assess- ing whether an RCT should be undertaken. Participants suggested that the intervention was easy, convenient, enjoyable, and relevant to their physical activity concerns. By completing all the intervention workbook activities and participating in phone calls and sessions, they also displayed excellent intervention com- pliance. In addition to goo d clinical utility and not over- burdening the clinic, the intervention appears to be ac- ceptable and feasible for the participants. For the CF po- pulation in particular who manage an arduous treatment burden, suffer from poor physical health, and display poor long term compliance with exercise training re- gimes, issues of feasibility are arguably of great impor- tance. For instance, Gruber et al. [45] note that althou gh their daily, home based cycling program for CF youth resulted in improved physiological and psycho-social health, the program was not perceived to be acceptable or enjoyable for the participants. From our developmen- tal qualitative pilot work, it can be concluded that our program is feasible and that an RCT can safely be un- dertaken. In developing such a larger scale trial, we will be able to ensure that the intervention is sensitive to the needs of this fragile population. Limitations There were several conceptual and pragmatic limita- tions associated with th e CF Chatters program. Based on our grounded theory of physical activity in CF, and lit- erature that underscores the importance of engaging parents in ill youths’ physical activity [40], the program was designed as a parent mediated intervention and se- parate child and parent manuals were developed. Upon starting the program, however, the adolescent case pa- tients—Chase and Layla—opted to participate without their parents. Instead, their parents facilitated transport to the counselling sessions and waited for them in the hospital cafeteria or clinic. In contrast, the child partici- pants Emily and Zoe activity engaged in the program with their parents. While this limitation required us to slightly modify our intervention delivery and prevented us from deliver- ing a uniform parent mediated program to all the par- ticipants, it is instructive. While there are invariably dif- ferences between biological and developmental age, the results from our case studies suggest that younger child participants desire to engage in the program with their parents. Indeed, they found the presence of parents to be satisfying and comforting and parents are valuable sources of knowledge for information that the child may forget. In contrast, the older adolescent participants de- sire to participate without their parents, or rather, with the informal facilitative support of their parent. It has been suggested that the central task for adolescents is individuation from the parent and the development of an autonomous self and distinct identity [65]. Concerns related to autonomy may be particularly heightened dur- ing this fragile developmental period. As such, it is likely that future CF Chatters child participants will en- gage in the program with parents. In contrast, adoles-  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 121 cents may wish to engage in the program alone and their desire for autonomy should be supported and encour- aged. Interventionists may wish to provide patients with a choice of parental involvement. Three sessions was adequate time to deliver the con- tent and to counsel the particip ants to enhance their phy- sical activity. The program is feasible, suggesting that it can easily be incorporated into clinical practice. With respect to the limitations of the intervention itself, the reminder and review phone calls home—which were interspersed between sessions–were often difficult for the researcher to conduct. Patients and parents were of- ten not at home at the time of the phone call, and were attending other scheduled activities. This was time con- suming for the researcher and required multiple phone calls home. Future interventionists should schedule a weekly reminder and review phone call to avoid this time expense. Additionally, given that the CF clinic is very busy during day time hours, sessions were sched- uled in the late afternoons and evenings. Given that children did not have to miss school, parents were plea- sed with the time of the appoint ments. As well, since the program did not interfere with the clinical day time pro- gram, clinical staff was appreciative of the program time. It was also pleasant to work with the participants in a quiet setting, free of day time interruptions. Thus, future interventionists should consider CF Chatters as an after- school or evening hospital program. Finally, there are clear limitations associated with adopting a qualitative, descriptive approach to investi- gate participants’ perceptions toward a physical activity program, and reliance on self report data collection tools. Such a participant centred evaluative approach is critical to ascertaining participants’ perceptions toward the pro- gram and offers valuable descriptive, interpretative, and exploratory information to ensure th at later interventions are grounded in the lives and experiences of potential users. However, in the absence of objective physical activity measures, and a well powered sample that is representative of the CF populace at large, the results are not generalizable beyond the study sample itself in the “classic” sense of generalizability. However, as sug- gested by Conrad and others [66], the findings may offer case generalizability or tran sferability to similar co ntexts, people, and places, serving as “proof of concept.” In this regard, the findings from this pilot study may account for how other CF patients resolve similar physical activ- ity dilemmas in other contexts. Such transferability as- sessments should be made by readers of this work who should judge the relevance of the findings to their clini- cal context based on a gradient of similarity. Guided by the MRC framework [30], the development of a CF Chatters feasibility trial is the next step. Such a feasibility trial should be characterized by a well pow- ered sample, objective measures of physical activity, and the inclusion of a usual care condition that does not re- ceive the CF Chatters interven tion. A feasibility trail will allow researchers to further address theoretical con- structs within our grounded theory, and tease out media- tors of physical activity b ehaviour change. We found that different techniques were effective for different partici- pants. Further research is required to stipulate the self regulatory skills that are most appropriate for the CF Chatters program. Psycho-education and contingency planning was the most effective approach for our more inactive patients and parents—Layla, Zoe, and Gretchen, and those participants that were experiencing greater disease burden—Layla and Emily. Alternatively, goal setting, planning, and recording were most effective for those already active patients and parents who were mo- tivated to further enhance their physical activity–Chase and Erik. Future research initiatives should work to- wards unraveling which behavioural self regulation skills and strategies are most appropriate for the diverse participants in the program. Generating such evidence will allow researchers to assess whether a definitive RCT should be conducted, examining the effectiveness of the physical activity behavioural counselling approach for the CF population. 5. CONCLUSIONS Despite the many benefits of physical activity for the CF population, many of these youth are not meeting the guidelines for physical activity for optimal growth and development. Existing intervention research is atheo- retical and tends to prescribe exercise training, rather than enjoyable physical activities of one’s choice. Fol- lowing a recent call by Hebestreit [67]—that behavioural counselling is critical for sustained physical activity in CF–the intervention described in this paper is timely. In addition to demonstrating the utility of the qualitative paradigm in developing conceptual models and theoreti- cally informed behavioural interventions, the CF Chat- ters program facilitated increased physical activity and quality of life. Where measures of psycho-social health and quality of life have not typically been included in intervention research, enhanced ph ysical quality of life is a particularly noteworthy finding. While further research and development is required to assess the effectiveness of CF Chatters, this study provides a usefu l template for the design of programs that are suitable and sensitive to the complex health and physical activity needs of this life limited population. REFERENCES [1] Moorcroft, A. (2004) Individualized unsupervised exer-  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 122 cise training in adults with cystic fibrosis: A one year randomized contro l l e d trial. Thorax, 59, 1074-1080. doi:10.1136/thx.2003.015313 [2] Nixon, P., Orenstein, D. and Kelsey, S. (2001) Habitual physical activity in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33, 30-35. doi:10.1097/00005768-200101000-00006 [3] Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry: Annual Data Report (2009). [4] Berge, J., Patteron, J., Goetz, D. and Milla, C. (2007) Gender differences in young adults’ perceptions of living with cystic fibrosis during the transition to adulthood: A qualitative investigation. Family Systems & Health, 2, 190-203. doi:10.1037/1091-7527.25.2.190 [5] Wheatley, C.M., Wilkins, B.W. and Snyder, E.M. (2011) Exercise is medicine in cystic fibrosis. Exercise Sport Science Review, 39, 155-160. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e3182172a5a [6] Moorcroft, A.J., Dodd, M.E. and Webb, A.K. (1997) Ex- ercise testing and prognosis in adult cystic fibrosis. Tho- rax, 52, 291-293. doi:10.1136/thx.52.3.291 [7] Nixon, P. A., Orenstein, D.M., Kelsey, S. F. and Doershuk, C.F. (1992) The prognostic value of exercise testing in patients with cystic fibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 327, 1785-1788. doi:10.1056/NEJM199212173272504 [8] Pianosi, P., LeBlanc, J. and Almudevar, A. (2005) Peak oxygen uptake and mortality in children with cystic fi- brosis. Thorax, 60, 50-54. doi:10.1136/thx.2003.008102 [9] Schneiderman-Walker, J., Pollock, S., Corey, M., Wilkes, D., Canny, G., Pedder, L., et al. (2000) A randomized controlled trial of a 3-year home exercise program in cystic fibrosis. The Journal of Pediatrics, 136, 304-310. doi:10.1067/mpd.2000.103408 [10] Williams, C.A., Benden, C., Stevens, D. and Radtke, T. (2010) Exercise training in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: Theory into practice. International Jour- nal of Pediatrics, 7. [11] Zach, M., et al. (1981) Effect of swimming on forced expiration and sputum clearance in cystic fibrosis. Lancet, 2, 1201-1203. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(81)91440-9 [12] Hebestreit, A., Kersting, U., Basler, B., Jeschke, R. and Hebestreit, H. (2001) Exercise inhibits epithelial sodium channels in patients with cystic fibrosis. American Jour- nal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 164, 443-446. [13] Moran, B. (2008) Physical training in cystic fibrosis. Cochrane data base of systematic reviews, 1, 1-12. [14] Singh-Grewal, D., Schneiderman-Walker, J., Wright, V., Bar-Or, O., Beyene, J., Selvadurai, H., et al. (2007) The effects of vigorous exercise training on physical function in children with arthritis: A randomized, controlled, sin- gle-blinded trial. Arthritis Rheumatology, 57, 1202-1210. [15] Takken, T., Elst, E. and van der Net, J. (2005) Patho- physiological factors which determine the exercise intol- erance in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Current Rheumatology Reviews, 1, 91-99. doi:10.2174/1573397052954235 [16] Takken, T., Spermon, N., Helders, P.J., Prakken, A.B. and Van Der Net, J. (2003) Aerobic exercise capacity in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Jeuvenile Rheu- matology, 30, 1075-1080. [17] Stephens, S., Feldman, B.M., Bradley, N., Schneiderman, J., Wright, V., Singh-Grewal, D., et al. (2008) Feasibility and effectiveness of an aerobic exercise program in chil- dren with fibromyalgia: Results of a randomized con- trolled pilot trial. Arthritis Rheumatology, 15, 1399-1406. doi:10.1002/art.24115 [18] Prasad, S. and Cerny, F. (2002) Factors that influence adherence to exercise and their effectiveness: Application to cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology, 34, 66-72. doi:10.1002/ppul.10126 [19] Klijn, P. , Oudshoorn, A., van der Ent, C., van der Net, J., Kimpen, J. and Helders, P. (2004) Effects of anaerobic training in children with cystic fibrosis: A randomized controlled study. Chest, 125, 1299-1305. doi:10.1378/chest.125.4.1299 [20] Orenstein, D., et al. (2004) Strength vs. aerobic training in children with cystic fibrosis: A randomized controlled trial. Chest, 126, 1204-1214. doi:10.1378/chest.126.4.1204 [21] Selvadurai, H., Blimkie, C., Meyers, N., Mellis, C., Cooper, P. and Van Aspersen, P. (2002) Randomized con- trolled study of in-hospital exercise training programs in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology, 33, 194-200. doi:10.1002/ppul.10015 [22] Schneiderman-Walker, J., Pollock, S., Corey, M., Wilkes, D., Canny, G., Pedder, L., et al. (2000) A randomized controlled trial of a 3-year home exercise program in cystic fibrosis. The Journal of Pediatrics, 136, 304-310. doi:10.1067/mpd.2000.103408 [23] Turchetta, A., Salerno, T., Lucidi, V., Libera, F., Cutrer, R. and Bush, A. (2004) Usefulness of a program of hospi- tal-supervised physical training in patients with CF. Pe- diatric Pulmonology, 38, 115-118. doi:10.1002/ppul.20073 [24] Gulman, V., de Meer, K., Backel, H., Faber, J., Berger, R. and Helders, P. (1999) Outpatient exercise training in children with cystic fibrosis: Physiological effects, per- ceived competence, and acceptability. Pediatric Pul- monology, 28, 39-46. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199907)28:1<39::AID-PP UL7>3.0.CO;2-8 [25] Verschuren O., Ketelaar, M., Gorter, J.W., Helders, P.J., Uiterwaal, C.S. and Takken, T. (2007) Exercise training program in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatric Ado- lescent Medicine, 161, 1075-1081. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1075 [26] Van Brussel, M., Takken, T., Uiterwaal, C.S., Pruijs, H.J., Van der Net, J., Helders, P.J., et al. (2008) Physical training in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Jour- nal of Pediatrics, 152, 111-116. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.06.029 [27] Schneiderman-Walker, J., Wilkes, D.L., Strug, L., Lands, LC., Pollock, S.L ., Selva durai, H.C., Hay, J., Coates, A.L. and Corey, M. (2005) Sex differences in habitual physi- cal activity and lung function decline in children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatrics, 147, 321-326. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.03.043 [28] Wilkes, D.L., Schneiderman, J.E., Nguyen, T., Heale, L., Moola, F., Ratjen, F., Coates, A.L. and Wells, G.D. (2009) Exercise and physical activity in children with cystic fi- brosis. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 10, 105-109.  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 123 doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2009.04.001 [29] Kahn, E.B. , Ramsey, L.T., Brownson, R.C., Heath, G.W., Howze, E.H., Powell, K.E., et al. (2002) The effective- ness of interventions to increase physical activity: A sys- tematic review. American Journal of Preventative Medi- cine, 4, 73-107. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00434-8 [30] Rhodes, R.E. and Pfaeffli, L.A. (2009) Mediators of physical activity behaviour change among adult non- clinical populations: A review update. Annals of Behav- ioral Medicine, 37, S85. [31] Medical Research Council (MRC) (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: New guidance. London. [32] Moola, F., Faulkner, G. and Schneiderman, J. “No time to play”: Perceptions toward physical activity in youth with cystic fibrosis (CF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, In Press. [33] Moola, F.J., Faulkner, G., Kirsh, J.A. and Schneiderman, J. (2011) Developing exercise interventions for children with cystic fibrosis and congenital heart disease: Learn- ing from their parents. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12, 599-608.doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.07.001 [34] Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L. (1967) The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine, Chicago. [35] Charmaz, C. (2003) Grounded theory in the 21st century. In: Denzin, N. and Lincoln, Y., Eds., The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues (2nd Edition), Sage, London, 507-530. [36] Weed, M. (2009) Research quality considerations for grounded theory research in sport and exercise psychol- ogy. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10, 502-510. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.02.007 [37] Swisher, A. and Erickson, M. (2008) Perceptions of physical activity in a group of adolescents with cystic fi- brosis. Cardiopulomonary Physical Therapy Journal, 19, 103-113. [38] Moola, F., Faulkner, G., Kirsh, J. and Kilburn, J. (2008) Physical activity and sport participation in youth with congenital heart disease: Perceptions of children and parents. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 25, 49-70. [39] Lunt, D., Briffa, K. and Ramsay, J. (2003) Physical ac- tivity levels of adolescents with congenital heart disease. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 49, 43-50. [40] Bar-Mor, G., Bar-Tal, Y., Krulik, T. and Zeevi, B. (2000) Self-efficacy and physical activity in adolescents with trivial, mild, or moderate congenital cardiac malforma- tions. Cardiology in the Young, 10, 561-566. doi:10.1017/S1047951100008829 [41] Golan, M. (2006) Parents as agents of change in child- hood obesity from research to practice. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 1, 66-76. doi:10.1080/17477160600644272 [42] Golan, M., Kaufman, V. and Shahar, D. (2006) Child- hood obesity treatment: Targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. British Journal of Nutrition, 95, 1008-1015. doi:10.1079/BJN20061757 [43] Nader, P., et al. (1989) A family approach to cardiovas- cular risk reduction: Results from the San Diego health project. Health Edu cat ion, 16, 229-244. doi:10.1177/109019818901600207 [44] Smith, B. and Sparkes, A. (2008) Changing bodies, changing narratives and the consequences of tellability: A case study of becoming disabled through sport. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30, 217-236. doi:10. 1111/j.1 467-9566.2007.01033.x [45] ] Wilson, H. and Hutchinson, S. (1996). Methodological mistakes in grounded theory. Nursing Research, 45, 122-124. [46] Gruber, W., Orenstein, D., Braumann, K. and Huls, G. (2008) Health-related fitness and trainability in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology, 43, 953-964. doi:10.1002/ppul.20881 [47] Loughlan, C. and Mutrie, N. (1995) Conducting an exer- cise consultation: Guidelines for health professionals. Journal of the Institute of Health Education, 33, 78-82. [48] Bandura, A. (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall Inc, Englewood Cliffs. [49] Abraham, C. and Michie, S. (2008) A taxonomy of be- havior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27, 379-387. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379 [50] aranowski, T., Anderson, C. and Carmack, C. (1998) Mediating variable framework in physical activity inter- ventions. How are we doing? How might we do better? American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 15, 266-297. [51] Lewis, B.A., Marcus, B., Pate, R.R. and Dunn, A.L. (2002) Psychosocial mediators of physical activity be- havior among adults and children. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 26-35. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00471-3 [52] Rhodes, R.E. and Pfaeffli, L.A. (2009) Mediators of physical activity behaviour change among adult non-cli- nical populations: A review update. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37, s85. [53] Rhodes, R.E., Naylor, P.-J. an d McKay, H.A. (2010) Pilot study of a family physical activity planning intervention among parents and their children. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 33, 91-100. doi:10.1007/s10865-009-9237-0 [54] Stake, R. (2000) Case studies. In: Denzin, N. and Lincoln, Y., Eds., The Handbook of Qualitative Research, Sage, Thousand Oaks, 236-247. [55] Faulkner, G. and Biddle, G. (2004) Physical activity and depression: Considering contextualityand variabilit y. Jour- nal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26, 3-18. [56] Flyvbjerg, B. (2004) Five misund erstandi ngs abou t c ase— study research. In: Seale, G., Gubrium, J. and Silverman, D., Eds., Qualitative Research Practice, Sage, Thousand Oaks, 390-404. doi:10.4135/9781848608191.d33 [57] Kvale, S. (1996) Interviews: An introduction to qualita- tive research interviewing. Sage, Thousand Oaks. [58] Mason, J. (2002) An introduction to qualitative research- ing. Sage, Thousand Oaks. [59] Faulkner, G., and Sparkes, A. (1999) Exercise as therapy for schizophrenia: An ethnographic study. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 21, 39-51. [60] Hay J.A. and Cairney, J. (2006). Development of the ha- bitual activity estimation scale for clinical research: A systematic approach. Pediatric Exercise Science, 18, 193- 202. [61] Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [62] Bandura, A. (1997) Self efficacy: The exercise of control.  F. J. Moola et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 ( 2011) 109-124 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/Openly accessible at 124 W.H. Freeman and Company, New York. [63] Frank, A. (1995) The wounded storyteller: Body, illness, and ethics. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [64] Smith, B. and Sparkes, A. (2008) Changing b odies, chang- ing narratives and the consequences of tellability: A case study of becoming disabled through sport. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30, 217-236. doi:10. 1111/j.1 467-9566.2007.01033.x [65] Glasscoe, C. and Smith, J. (2008) Through a mother’s lens: A qualitative analysis reveals how temporal experi- ence shifts when a boy born preterm has cystic fibrosis. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13, 609-626. doi:10.1177/1359104508096772 [66] Noom, M., Dekovic, M. and Meeus, W. (1999) Auto- nomy, attachment and psycho-social adjustment during adolescence: A double edged sword? Journal of Ado- lescence, 22, 771-783. doi:10.1006/jado.1999.0269 [67] Conrad, P. (1990) Qualitative research on chronic illness: A commentary on method and conceptual development. Social Science and Medicine, 30, 1257-1263. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(90)90266-U [68] Hebestreit, H., Kieser, S., Junge, S., Ballman, M., Habe- streit, A. and Schindler, C. (2010) Long term effects of a partially supervised conditioning programme in cystic fi- brosis. European Respiratory Journal, 35, 578-583. doi:10.1183/09031936.00062409