Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 901-909 doi:10.4236/me.2011.25101 Published Online November 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 901 An Economic Evaluation of New Optional Calling Plans in Telephone Service Sung Ho Seol1, Moon-Soo Kim2* 1Electronics & Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI), Daejeon, Korea 2Department of Industrial & Management Engineering, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Yongin-si, Korea E-mail: *kms@hufs.ac.kr Received August 31, 2011; revised October 12, 2011; accepted October 26, 2011 Abstract With the growth of competition in the telecommunication market, optional calling plans were introduced in 1980s, have expanded dramatically in 1990s and now have become widespread rate systems in many coun- tries. In this respect, the Korean telephone market also provided various rates. Compared to other countries, however, a special optional calling plan has activated in Korean market. It is a unique calling plan where rates are based on previous calls made. That plan provides high market performance, yet it arouses criticism in the industry. There are questions raised by professionals in the industry if that plan based on previous call made is fair to consumers and is it more effective than other type of calling plan. Considering this circum- stance, we theoretically analyzed and compare between rate system based on previous call made and differ- ent rate system including unlimited flat-rate and BOT, by mainly the perspective of efficiency. The results show that rate system based on past calling patterns will be economically more efficient compared to other types. Therefore, it is necessary not to prohibit this rate system, rather selectively regulating or other flexible means of regulation is desirable, nevertheless it has some week point. Keywords: Optional Calling Plans, Telephone Service, Pricing Scheme, Social Welfare, Regulation, Korea 1. Introduction The first OCP (optional calling plan) introduced in June 1984 by AT & T in the name of the “Reach-out Amer- ica,” became popular and a marketing success [1]. Once into the 1990s, with the accelerating competition in the telephone market, optional calling plans which allow consumers to freely choose a rate structure had expanded dramatically and were offered in many countries although it drives up congestion costs to consumers due to a large variety of rate structures. US provider Verizon provides several different pricing options for its long-distance services (flat rate pricing for local calls), including a flat tariff, two-part tariff and per-minute charge. Optional plans, applying to bundles including local and long-dis- tance calls, and internet access service, are also gaining popularity in the US and another example, UK provider BT offers a two-part tariff, partial flat pricing and flat rate plan. It has also discontinued its standard rate plan, a per-minute pricing plan, in favor of more flexible pricing plans [2]. Development of attractive OCPs has emerged as one of the key factors to succeed in the telephone business, especially under market situation which is get- ting much faster in substitution mobile traffics for fixed telephone ones and rapidly decreasing calling demand of fixed telephone. In past, there were so many researches to examine economic welfare on telephone pricing scheme including optional plan and calling patterns such as Alleman [3], Mictchell [4], Wilkinson [5], Park, Wetzel & Mitchell [6], Park, Mitchell, Wetzel & Alleman [7] and Train, McFadden & Ben-Akiva [8], etc. Those studies have emphasized the theoretical analysis of various tariffs in telecommunications industry, especially; Train et al. [8] indicated the necessity that evaluation on the welfare implications of numerous voluntary calling options is an important direction for future research. Several studies analyzing efficiency of optional calling plans in tele- phone service are as follows. Martins-Filho and Mayo [9] evaluated welfare effects of the geographic patterns of  S. H. SEOL ET AL. 902 telephone pricing like adoption of extended area service in the 4 major metropolitan areas in Tennessee US which noticeably enhanced consumer surplus. More in recent, Miravete [10] suggested that a menu of optional two-part tariffs dominates any other pricing strategy from analyz- ing the expected welfare associated with standard nonlinear pricing and optional tariffs by using informa- tion directly linked to the type of individual consumers. And Masuda and Whang [11] developed the optimal menu of FUT (fixed-up-to) plans which is almost same to BOT-type plan in our paper and showed it delivers as good performance as any nonlinear pricing scheme. Oth- erwise, Jensen [12] showed some examples from tele- communications industry where firms offer two part tar- iffs with free call minutes to low demand segments. KT, the dominant telephone service provider in Korea, has planned a new OCP, ARPU (Average Revenue Per User)-based pricing, to activate the call effectively to decreasing the volume of call traffic and its revenue due to the substitution between fixed and mobile call as well as Internet telephony. But the Korean regulator has been anxious about decreasing the consumers’ surplus consid- ering that the new OCP can be operated like a price-dis- crimination by the dominant provider. This study ana- lyzes economic effects of the ARPU-based pricing in terms of provider- and consumer-side with the existing OCPs including a linear pricing and examines regulatory implication for Korean telephone service industry. The rest of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 examines the background of introduction of ARPU- based pricing system and economic research method for the new OCP in Korean telephone industry. Section 3 describes a simple economic model used in this study and presents the range of optional calling plans consid- ered and under the model analyzes a theoretical explora- tion of the economic effects of each of the optional call- ing plans and their comparative analysis. In Section 4, we discuss the validation of the potential benefits of the ARPU-based pricing system in terms of the social wel- fare, price discrimination and predatory pricing-related issues. Finally, in Section 5, we present policy implica- tions derived from our findings and directions for future research. 2. A New Optional Calling Plan Unlike in the advanced countries, in Korea, over 70% of fixed-line telephone users are subscribed to standard rate plan such as a simple two-part tariff. This has much to do with the meager choice of available optional calling plans; there is only one optional pricing model in use in Korea. The standard rate-centered pricing policies among Korean telephone service providers, as they fail to ad- dress diverse needs of consumers, are responsible, at least in part, for the current stagnancy of the fixed-line market and are contributing to the acceleration of the phenomenon of substitution of fixed-line services by mobile services. As shown Figure 1, while the mobile call volume has been continuously increased in originat- ing call from mobile network as well as terminating call on one, the total volume of fixed-telephone call has been decreased since 1996, in particular, it shows steep de- creasing in fixed to fixed call. In order to activate fixed telephone call demand, KT looked into offering an ARPU-based optional calling plan, whereby the rate is determined according to the average past usage. At first, this was not approved by the Korean Ministry of Information and Communication (MIC)1, which recommended that it be replaced by a BOT (Block of Time)-type plan or an unlimited flat rate plan, finding price discrimination under the former to be more than others. The purpose of new optional calling plans adoption is increasing consumer surplus nonetheless enduring a de- gree of price discrimination in the pricing. Thus, the regulatory stance toward optional calling plans must be based on an economic analysis determining which of the optional pricing models (ARPU-based pricing, BOT or unlimited flat rate model) are more likely to enhance consumer surplus, all the while enduring the discrimina- tory effect against users which their use entails. KISDI [14] analyzed different types of pricing combinations, to determine the optimal price range, related consumer sur- plus and social welfare under the scenario that the tele- phone market is a monopoly market, assuming that het- erogeneous consumers exist in this market and that the goal of the monopoly supplier is to maximize the profit. They concluded the OCP was more efficient than the existing linear pricing and two-part tariff. And Yeom [15], assuming a situation where a monopoly supplier Figure 1. The trend of Fixed and mobile call traffic in Ko- rea [13]. 1It was renamed KCC (Korea Communications Commission) in 2008. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  903 S. H. SEOL ET AL. with a constant marginal cost and a single pricing system adds an optional calling plan, calculated the price range and costs which can increase both provider profit and consumer surplus. Meanwhile, Byun [16] explored opti- mal designs for a BOT rate system, allowing a monopoly supplier to maximize profits in a market where consum- ers are heterogeneous. And in real world, a similar plan to ARPU-based pricing, so-called Tailored Flat Pricing (TFP) plan for only three months in 2002 by KT ap- peared a marketing success that the churning number of existing subscribers to TFP was more than 6.2 million as of end of May 2009 and took the No. 1 ranking among fixed telephony plans except for standard pricing plan as well as increased about 31% in call amount compared with previous call amount under the standard pricing plan [17]. This study is to examine the validity of introducing a new ARPU-based rate system in telephone service mar- ket of Korea. This analysis, assuming that an optional calling plan is added to an existing per-minute charge system, looks for the call pricing scheme most beneficial for consumers by comparing ARPU-based pricing with other types. We considered a wider variety of pricing structures, including APPU-based and BOT-style models, to derive policy implications for this latest issue. 3. A Simple Model and Comparative Analysis 3.1. A Simple Model and Analytical Method A theoretical analysis conducts in this study rests on a number of assumptions. First of all, we assume that the price decided by a monopoly supplier covers the entire cost of providing services, and that the marginal cost is 0. Further, fixed-line telephone services provided by the monopoly supplier, whilst serving a large number of cus- tomers, are assume to yield different benefits to different consumers. To capture the diversity of consumption pat- tern, consumers are classified into different types, and different types of consumers are assigned the t, i.e., be- cause consumer is heterogeneous, instead of aggregated demand function which used in many cases of economic analysis, individual demand function is used in this model. For all t, a uniform distribution is assumed. In other words, the probability density function of t is f(t) = 1 for t [0, 1]. The demand curve for an individual cus- tomer with the above characteristics assumes to be p = t – qt. Although there are many types for individual demand function used in economic analysis, an individ- ual demand function in this paper is supposed to be lin- ear for simplicity and has equal slope not to cross be- tween demand curves, then all consumer’s characteristics are described by his maximum value t. Further, we as- sume that the operator’s behavior is driven by maximiz- ing profits, and that the regulatory body is only con- cerned by the type of optional calling plans which the operator offers, and does not interfere with the price it- self. This is because the new OCP can’t be designed to be unduly high or low if existing standard rate plan (as a based plan) is assumed to be unchanged, and each con- sumer is rational. Thus potential problems for regulator to consider are closely connected with structure or type of OCP. Then the possible maximum of social welfare sum- med the producer profits and consumer surplus will be 12 0 11 d 26 tt . We consider a simplified scenario that the fixed-line telephone service market being studied practices only a standard pricing like per-minute charge system, and that the operator is looking into introducing one of the four pricing models: unlimited flat fee, ARPU-based unlim- ited flat fee, BOT-style plan and ARPU-based plan with free calling times. Although there are some kinds of OCP in real world, as far as we know in telephone service market of Korea, they all do not have so many subscrib- ers except for TFP, which belongs to the type of ARPU- based flat fee plan, and new potential customer can’t subscribe to the TFP due to subscription restriction as mentioned. Therefore, the model simplifies the actual situation as if only standard pricing plan existed before new OCP adopted with the view of new consumer. Un- der the assumption of demand function and market con- ditions, after analyzing the economic effect of per-min- ute charging system, that of four-possible OCPs with the per-minute charging system is sequentially analyzed and carried out comparison of economic effects among 5 pricing schemes. 3.1.1. Per-Mi nute Charging System Alo ne Assume that the current standard tariffs are the rates de- termined through the service provider’s optimization behavior. If the provider charges its fixed-line telephone services at the rate “p”, only those consumers for whom t > p will purchase them. In this case, the objective func- tion of this provider will be expressed as follows. 1 max πd p pptp t (A-1) Then, the first derivative condition for maximizing profit would be (A-2) whereby the profit function, dif- ferentiated with respect to p, equals 0, given below: 2 dπ31 2 d2 2 pp p0 (A-2) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. H. SEOL ET AL. 904 The optimum per-minute rate, calculated using (A-2), is p* = 1/3, and the provider profit, * = 2/27 = 0.0741. Meanwhile, the consumer surplus (CS) is 2 1 1/3 11 d 0.0494 23 tt at p* = 1/3. 3.1.2. Unlimited Flat Fee Plan In this case, p* = 1/3, the existing metered rate, calcu- lated using (A-2), remains in place, even after the new unlimited flat fee system is introduced, as an optional plan. Let us assume t1 marginal consumers who are un- sure whether or not they should go for a per-minute charge plan and t2 borderline consumer hesitating be- tween a per-minute charge plan and a flat fee plan. Then the function of profit for the provider must satisfy the incentive compatible constraint, requiring that utility gained by t2-type consumers through the flat fee plan be equal to that gained through the per-minute charge plan. 2 12 1 11 2 max πd t tt pt ptFt d (B-1) s.t. 2 21 2 22 1 22 tp tF (incentive compatible constraint equation for type t2) 1 1 3 p (existing standard tariff pricing maintained) t1 and t2, solved using the first derivative condition for the maximization of provider profit, yield t1 * = 1/3 and t2 * = 5/6. If one substitutes these values into the incentive compatible constraint equation, this yields an optimum flat rate price (F2 *) of 2/9. Further, by substituting this value of optimum price and consumer type t1 * into (B-1), we obtain the provider profit of 17/216=0.0787. In this case, the consumer surplus is 2 5/61 2 1/3 5/6 11 12 dd 0.0540 23 29 tt tt indicating a clear increase in user welfare over the situa- tion in which no other price option existed except per- minute charge. 3.1.3. A RPU-Based Flat Fee Plan Now suppose that the optional calling plan added is an ARPU-based flat fee plan, instead of a simple flat fee plan. An ARPU-based flat fee plan allows consumer “t” to make unlimited calls for a fixed fee corresponding to his or her average spending call under the per-minute charging plan (ARPUt) plus ARPUt, as illustrated in the graph in Figure 2. “A” in the graph in Figure 2 is the Figure 2. Change in consumer surplus when switching to ARPU-based flat fee plan. additional payment incurred by the customer switching to this plan, and B, the gain in utility realized by the same customer. The change in net utility, therefore, is equal to B – A. Hence, a rational consumer would not switch to the new pricing model, unless B – A > 0. Let us refer to marginal consumers who are wondering whether they subscribe or not as t1, and the other border- line category of consumers hesitating between the ARPU- based optional plan and the per-minute charge subscrip- tion as t2. Especially, in this case heavy consumers re- main to the per minute charge plan, middle-ranged con- sumers go to the ARPU-based flat fee plan and lighter users do not subscribe. The objective function of the provider, then, is (C-1), given below: 2 12 1 11 11 max π1dd t tt pt ptpt pt (C-1) s.t. 2 1 12 12 p pt p (area A = area B in Figure 2, incentive compatible constraint for type t2) 1 1 3 p (existing standard tariff pricing maintained) We can now determine the first derivative condition for maximizing the provider profit. The first partial de- rivative of objective function by t2 is positive for all t2. That means the boundary condition, t2 = 1 and the opti- mum *, which can induce many consumers including heavy consumers, is 1/4 = 0.25. In this case, the provider profit is 5/54 = 0.0926, and the consumer surplus, 2 1 1/3 11 1 1d11/162 0.0679 2433 ttt . 3.1.4. A BOT-Type Plan We will now suppose that the new optional calling plan added is a BOT-type plan. A BOT-type plan has a three- tier pricing system, consisting of (F2, h2, p), as shown in Figure 3. Here, F2 is a fixed fee, h2 is the maximum min- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  905 S. H. SEOL ET AL. Figure 3. Pricing structure in a BOT-type plan. utes of call at no additional charge over the fixed fee, and “p”, the rate per minute charged on calls over and above the maximum minutes of call. Let us call t1 marginal consumers who are wondering whether they should go for a per-minute charge subscrip- tion, and t2 borderline subscribers who straddle between the per-minute charge and the BOT-type calling plan. The provider’s objective function, in this case, will be written as (D-1) below. The reason why the profit func- tion in (D-1) has three terms is because those customers, belonging to the [t2, 1] group subscribed to the BOT-type calling plan, who meet the condition, t > h2 + p, are charged an additional cost of p(t – p – h2) for their over usages above h2. Each customer who belongs to the sub- group [t2, h2 + p] pays only F2 for her call usage. For example, borderline customer’s individual demand for price p is t – p = (h2 + p) – p = h2. That means borderline customer fully uses amount of maximum minutes of call without additional charge by customer rationality. How- ever, each customer who belongs to other sub-group [h2 + p, 1] pays F2 as a fixed fee plus p(t – p – h2) as an ad- ditional charge which is proportionate to over usage above h2. 2 122 11 11 22 max πdd t tthp pt ptFtpt pht d (D-1) s.t. 2 21 2 22 1 22 tp tF (incentive compatible constraint equation for subscriber type t2) 1 1 3 p (existing standard tariff pricing maintained) The incentive compatible constraint equation requires that utility gained by t2 consumer through BOT-style plan be equal to that gained through per-minute charging plan. If we denote optimal free calling times to maximize objective function as h2 *, then optimal BOT scheme is expressed as (F(h2 *), h2 *, p(h2 *)). To maximize global objective function, firstly F must satisfy to incentive compatible constraint equation and p must be such a price to maximize local objective function, which is revenue through additional charge2. After substituting two first derivative conditions into objective function of (D-1), total differential by the h2 gives optimal solution h2 * = 2/3. Hence, the optimal BOT pricing system would have (F2 * = 16/81, h2 * = 2/3 and p* = 1/9)3. Thus, the provider’s profit, 7/9 1 1/3 7/9 11 1617 dd 0.07956 33 8199 tt tt , and the consumer surplus, 2 7/9 1/3 22 2 1 7/9 11 CS d 23 161 2 17 d0.05487. 281232 9 tt tttt 3.1.5. ARPU-Based Plan with Free Calling Times An ARPU-based plan with free calling times is similar to BOT-type plans, insofar as a fixed fee covers a set num- ber of free minutes, and users pay an overage charge for minutes beyond the free minutes. It is similar also to the ARPU-based flat fee system, discussed earlier, in that the fixed fee is set to an amount roughly equivalent to a user’s monthly payment under the per-minute charging system. Concretely, the fixed fee paid by a customer switching to an ARPU-based plan with free calling times corre- sponds to (1 + ′)ARPUt, and this fee allows him or her to talk for a total duration corresponding to (1 + ) of the habitual call time. Minutes beyond this are charged “p” per minute. Let us assume t1 marginal consumers who are unsure whether or not they should subscribe and t2 borderline consumer hesitating between an ARPU-based plan with free calling times and a per-minute charge plan. Then the objective function of the provider, where the increase of first term is larger than the sum of decreases of second and of third term due to the marginal increase of t2, is (E- 1) given below: 2 1 1 1 2 11 1 1 1 11 maxπ1d 1d d t t pp t t pt pt pt pt pt pt pt (E-1) 2First derivative conditions are respectively F(h2) = h2/3 – (h2 h2)/18 and p(h2) = (1 – h2)/3. 3This solution was checked numerically by computer simulation. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. H. SEOL ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 906 s.t. 2 221 2121 11 2 tp tp ptp 2 (incentive compatible constraint for t2) an ARPU-based flat fee plan, by keeping the free min- utes to a moderate number, and instead, setting the over- age rate to a reasonable range, for example, not exces- sively low compared to the standard rate. 1 1 3 p (existing standard tariff pricing maintained) Consumer surplus, on the other hand, is smaller under an ARPU-based plan with free calling times, designed to maximize the provider’s profit, than under an ARPU- based flat fee plan; The optimal design for the provider to realize maxi- mum profit should have many consumers up to the type t = 1 become the subscriber of the ARPU-based plan with free calling times. This would mean ′ = 1/4, if 1/2 and ′ = – 2, if < 1/2. Subscribers to a ARPU-based plan with free calling times may be distinguished into sub-group [t1, t3] whose usage exceeds the set limit of free calls, and sub-group [t3, 1] whose usage is most of- ten within this limit. Further t3 the boundary subscribers between these two sub-groups, must satisfy the equation (1 + )(t3 – p1) = t3 – p; in other words, t3 = (1 + )/3 – p/ . The function of provider profit, meeting these con- ditions, would be as follows: 2 1 1/3 13 13 4 CSd 0.0576 81 812 tt t . 3.2. Comparison of Economic Effects 1 3 1 1 11 1 2 2 max π1d 1d 21 1 2723 t t t pt pt pt pt pt pp (E-2) The economic effects of each optional calling plans ex- amined above are listed in the Table 1. Figures in the Table 1 reveal that optional call plans, regardless of their type, result in an increase in consumer surplus, over the per-minute charge only pricing system, as long as there are a sufficient number of subscribers to cover the cost of offering the new plan. This result, consistent with the basic arguments of Samuelson’s revealed preference theory, points to the potentially beneficial effect of the introduction of optional calling plans on the Korean fixed-line telephone service market, a market where few price options are available. “p” and “ ” satisfying the first derivative conditions of (E-2) are respectively 1/9, 1/3. Substituting those into (E- 2) yields a maximum profit of 0.09876. What this sug- gests is that the provider can realize greater profit through an ARPU-based plan with free calling times than Which of these plans, then, would be the best and most beneficial for the Korean market? The results shown in the Table 1 provide theoretical evidence that both an ARPU-based flat fee plan and an ARPU-based Table 1. Comparison of economic effects. Per-minute Charge Per-minute Charge + Flat fee plan Per-minute Charge + ARPU-based flat fee plan Per-minute Charge + BOT plan Per-minute Charge + ARPU- ased plan with free calling times Charge per minute 1/3 1/3 1/3 1/3 1/3 Fixed fee 2/9 125% of ARPU 16/81 122% of ARPU Free minutes 2/3 150% of ARPU Overage rate 1/9 1/9 Provider profit 0.0741 0.0787 0.0926 0.07956 0.09876 Consumer surplus 0.0494 0.0540 0.0679 0.05487 0.0576 Social welfare (SW) 0.1235 0.1327 0.1605 0.13443 0.15636 % of SW to maximum SW(1/6) 74.1% 79.6% 96.3% 80.7% 93.8%  907 S. H. SEOL ET AL. plan with free calling times are superior to a flat fee plan or a BOT-style plan. It should be of course remembered that this conclusion assumes rational decision-making on the part both of the provider and consumers. An ARPU-based plan results in more substantial in- creases in provider profit and consumer surplus than a flat fee or BOT-style plan, very simply because it is more attractive to consumers and will generate a stronger market response. Let us suppose that there are five con- sumers we will call A, B, C, D and E, as in Figure 4, and that the average number of minutes spent on fixed-line calls is in increasing order, it being the lowest for A and the highest for E. The flat fee plan will only attract peo- ple like E with a high level of usage. The concentration may be somewhat less for a BOT-style plan, which could attract D, in addition to E. In comparison, an ARPU- based plan can interest most users except A, whose usage is so low that he or she may not consider signing up even for a per-minute charging plan. As the subscriber base includes B, C, D and E, an ARPU-based plan will natu- rally result in a larger increase in consumer surplus. In other words, an ARPU-based pricing model will yield greater effect as it is likely to be adopted by both heavy and less heavy to moderate users of fixed-line calls. 4. Discussions for Pricing Regulation on Telephone Market In what preceded, we examined whether an ARPU-based optional calling plan can contribute to the increase of consumer surplus and whether the increase of consumer surplus was greater in size than the corresponding in- creases that may be expected from other alternatives, such as a flat fee or BOT-style plan, using a simple eco- nomic analysis model. In this section, we will attempt a more global assessment of ARPU-based optional calling plans, by examining consumer surplus from an empirical perspective and considering issues such as potential price discrimination of users and predatory pricing associated with the practice of calling plans. We will begin by tak- ing a close look at a concrete example of an optional calling plan, the one by KT, which considered. For the sake of convenience, we will refer to this plan as Y; as can be seen in the Table 2 below, the actual values of ′, Table 2. Product concept of calling plan Y. Item Additional Charge Free Minutes Discount for calling more than Free Minutes ′ of ARPU ′ of ARPU Calling Plan Y ″ of ARPU ″ of ARPU % ″, ′, ″, , being confidential business information, were kept undisclosed. As the calling plan Y is to be introduced in addition to the existing standard pricing system, consumer-side util- ity should remain at its previous level or exceed it, pro- vided that the new option does not entail congestion costs. The question, therefore, is whether the introduc- tion of calling plan Y, detailed in the Tabl e 1, can result in a meaningful increase in consumer surplus. The an- swer, according to our analysis, is “Yes”. This is because the increase in utility can be sizeable, as long as the value of ′ or ″, the number of free minutes under Y, is large enough. Benefits for consumers will include no longer having to think about incurring additional costs when staying on the phone for extended periods [18], the ability provided by the fixed fee, of hedging against fu- ture uncertainties and risks associated with fluctuating demand [19], and having the option of choosing a rate scheme more advantageous to one’s usage pattern [1]. Based on these considerations, we calculated the dis- tribution of surplus among economic players, assuming that subscribers to Y will enjoy about a half of the addi- tional utility brought about by an ARPU-based flat fee plan, over and above that provided by a per-minute charging system, which was measured through a con- sumer survey. The distribution of surplus between con- sumers and producers, according to this calculation, was approximately 71% vs. 29%. This result suggests that the profit realized by a monopoly supplier, through the in- troduction of calling plan Y, was far from excessive, and that the benefit for consumers being significantly more important than the latter, the plan was in fact a win-win product, for mutual gain of the provider and customers. As has been mentioned earlier, Y is a calling plan, whereby the price of a call is in part determined by the past call volume of a user or the average telephone ser- vice spending. This pricing practice may, therefore, be liable to accusations of price discrimination. According to Stigler [20]4, price discrimination is inevitable and inherent in all optional calling plans. The question is not whether or not price discrimination is practiced, but rather whether it is practiced within an acceptable level. Y being a calling plan using a non-linear pricing struc- ture, price discrimination involved in it falls into the category of second order price discrimination. It is, however, undeniable that the degree of price discrimina- tion involved in Y is more marked than ordinary non- inear pricing-based call products. l 4Stigler [20] states that a firm price discriminates when the ratio o rices is different from the ratio of marginal costs for two goods of- fered by a firm. And Stole [21] has advanced a broader definition tha rice discrimination exists when prices vary across customer segments that cannot be entirely explained by variations in marginal cost. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  S. H. SEOL ET AL. 908 Figure 4. Subscr ibe r c a te gories by type of OCPs. To determine whether price discrimination practiced in calling plan Y is excessive and unfair, we resorted to the four criteria proposed by Bonbright [22]; 1) Is the price discrimination intended to generate needed revenue? 2) Do all parties stand to benefit from the practice? 3) Is there sufficient proof that the practice contributes toward covering long-run incremental cost increase? 4) What are the effects of the practice on competitors? Our analysis revealed that Y satisfied three of the four conditions, except criterion (1). KT being not a government-owned firm, criterion (1), in this case, was less relevant than the others. Of the four criteria formulated by Bonbright, criterion (3) is the one most closely related to whether a pricing method is predatory. Predatory pricing refers to selling products or services at very low prices with the intent to keep newcomers from entering the market or driving competitors out of the market. A two-tier rule is com- monly used to determine whether a pricing method is predatory. The first tier is the range above the average cost, and a price within this range clears a provider of the suspicion of predatoriness. If the price is below the av- erage cost, situated somewhere between the average variable cost and the average cost, considered as the gray zone, further inquiries are undertaken to establish whether or not the pricing is predatory. Prices under calling plan Y, detailed in the Table 2, are clearly above the average cost—evidence that no predatory pricing is involved in this plan. In order to ver- ify whether prices under calling plan Y are above the average cost, one needs to estimate the increase in call volume among subscribers switching from a per-minute charge plan to Y. We judged that the increase in call volume would not exceed 30%, given that Y is a plan having a pricing structure that is only partially flat fee- based. We therefore concluded that the pricing method under Y is not predatory. 5. Concluding Remarks ARPU-based pricing is clearly a very original pricing model, as the rate is decided on the basis of the past us- age or average call spending of a customer. The obvious disadvantage of this pricing method is that it involves a greater degree of price discrimination than other non- linear pricing-based calling plans such as BOT-type plans. This disadvantage comes with the offsetting ad- vantage that ARPU-based calling plans are more effec- tive in achieving improvement both in providers’ profit and consumer surplus than others of its kind, and are more likely candidates to successfully stimulate the fixed- line telephone service market. This study examined whether ARPU-based optional calling plans can be more efficient than other optional calling plans, using both a theoretical and empirical ap- proach. We found that an ARPU-based plan, similar to Y, will bring about a sizeable increase in consumer surplus. Furthermore, this study found no evidence warranting the concern of price discrimination or predatory pricing: the degree of price discrimination in the calling plan Y was moderate, well within the acceptable range, and the prices offered under the plan did not constitute predatory pricing. There are currently in Korea, ARPU-based optional calling plans, similar to Y, offered by service provider providers. Consumers are responding positively to these products, and a substantial number of users are switching to the new plans. Allowing these plans, we believe, has been a judicious course of action on the part of the regu- lator, having carefully weighed the pros and cons of ARPU-based pricing, decried as irregular or odd pricing practices and accused of price discrimination, on the one hand, and praised for contributing to consumer surplus and balanced industrial growth, on the other. A unilateral stance against ARPU-based pricing must be avoided, and related plans examined on a case-by-case basis, to de- termine their potential benefits and ramifications, using various criteria of judgment. This study has the following limitations which need to be addressed in future research: First, we used a simpli- fied model which assumes a uniform distribution of consumers. Hence, future research should verify whether the increase in consumer surplus brought about by ARPU-based calling plans will still be greater than that by other plans, when using the gamma distribution or other models more closely capturing the actual call vol- ume distribution. Second, we treated BOT-type calling plans as a single category, whereas, in reality, there are Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME  909 S. H. SEOL ET AL. many variants of this pricing model. Third, more impor- tant thing, although subscribers to ARPU-based plan in Korea showed a considerable increase in call amount compared with previous one, practical reductions in call traffic of fixed telephony service from longer term, which result by demand uncertainty, will be more critical issue from carrier as well as policy maker. This uncer- tainty problem on amount of call traffic needs to consider a factor of demand model. Future research should, there- fore, make appropriate changes to the research model to remedy this. 6. Acknowledgements This work was supported by Hankuk University of For- eign Studies (HUFS) Research Fund of 2011. 7. References [1] H. W. Choi, I. J. Kim and T. S. Kim, “Contingent Claims Valuation of Optional Plan Contracts in Telephone In- dustry,” International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2002, pp. 433-448. [2] OFCOM (Office of Communications), “Investigation against BT about Potential Anti-Competitive Exclusion- ary Behavior,” 2004. [3] J. Alleman, “The Pricing of Local Telephone Service,” Office of Telecommunications Special Report, US De- partment of Commerce, Vol. 77, No. 14, 1977. [4] B. M. Mitchell, “Optimal Pricing of Local Telephone Service,” American Economic Review, Vol. 68, No. 4, 1978, pp. 517-537. [5] G. Wilkinson, “The Estimation of Usage Repression un- der Local Measured Service: Empirical Evidence from the GTE Experiment,” In: L. Courville, , A. de Fontenary and R. Dobell Eds., Economic Analysis of Telecommuni- cations: Theory and Applications, North-Holland Press, Amsterdam, 1983. [6] R. Park, B. Wetzel and B. Mitchell, “Price Elasticities for Local Telephone Calls,” Econometrica, Vol. 51, No. 6, 1983, pp. 1699-1730. doi:10.2307/1912113 [7] R. Park, B. Mitchell, B. Wetzel and J. Alleman, “Chang- ing for Local Telephone Calls: How Household Charac- teristics Affect the Distribution of Calls in the GTE Illi- nois Experiment,” Journal of Economics, Vol. 22, 1983, pp. 339-364. [8] K. Train, D. McFadden and M. Ben-Akiva, “The Demand for Local Telephone Service: A Fully Discrete Model of Residential Calling Patterns and Service Choices,” RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1987, pp. 109-123. doi:10.2307/2555538 [9] C. Martins-Filho and J. Mayo, “Demand and Pricing of Telecommunications Services: Evidence and Welfare Implications,” RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 24, No. 3, 1993, pp. 439-454. doi:10.2307/2555967 [10] E. J. Miravete, “The Welfare Performance of Sequential Pricing Mechanisms,” International Economic Review, Vol. 46, No. 4, 2005, pp. 1321-1360. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2354.2005.00369.x [11] Y. Masuda and S. Whang, “On the Optimality of Fixed- up-to Tariff for Telecommunications Service,” Informa- tion Systems Research, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2006, pp. 247-253. doi:10.1287/isre.1060.0097 [12] S. Jensen, “Implications of Competitive Nonlinear Pric- ing: Tariffs with Inclusive Consumption,” Review of Economic Design, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2006, pp. 9-29. doi:10.1007/s10058-006-0002-3 [13] KISDI, “An Empirical Analysis and Its Strategic Implica- tions for Call Substitution from Fixed to Mobile,” 2007. [14] KISDI (Korea Information Society Development Insti- tute), “Toward a Comprehensive Pricing Policy Adapted to the Competitive Market System,” 1997. [15] M. B. Yeom, “Economic Analysis of ICT Service Op- tional Calling Plans,” Economic Papers, Vol. 14, 1998, pp. 61-87. [16] J. W. Byun, “Block of Time Tariff with Heterogeneous Consumers,” ICT Policy Studies, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2005, pp. 125- 148. [17] S. H. Seol and S. C. Kweon, “Economic Effect Analysis of the Introduction of Tailored Flat Pricing for Fixed Line Telephone Service,” Electronics & Telecommunications Research Institute, Daejeon, 2005. [18] D. Prelec and G. Loewenstein, “The Red and the Black: Mental Accounting of Savings and Debt,” Marketing Sci- ence, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1998, pp. 4-28. doi:10.1287/mksc.17.1.4 [19] B. Hayes, “Competitions and Two-Part Tariffs,” Journal of Business, Vol. 60, No. 1, 1987, pp. 41-54. doi:10.1086/296384 [20] G. Stigler, “The Theory of Price,” Macmillan, New York, 1987. [21] A. Stole, “Price Discrimination and Imperfect Competi- tion,” Mimeo, 2003. [22] J. C. Bonbright, “Principles of Public Utility Rates,” Co- lumbia University Press, New York, 1961. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME

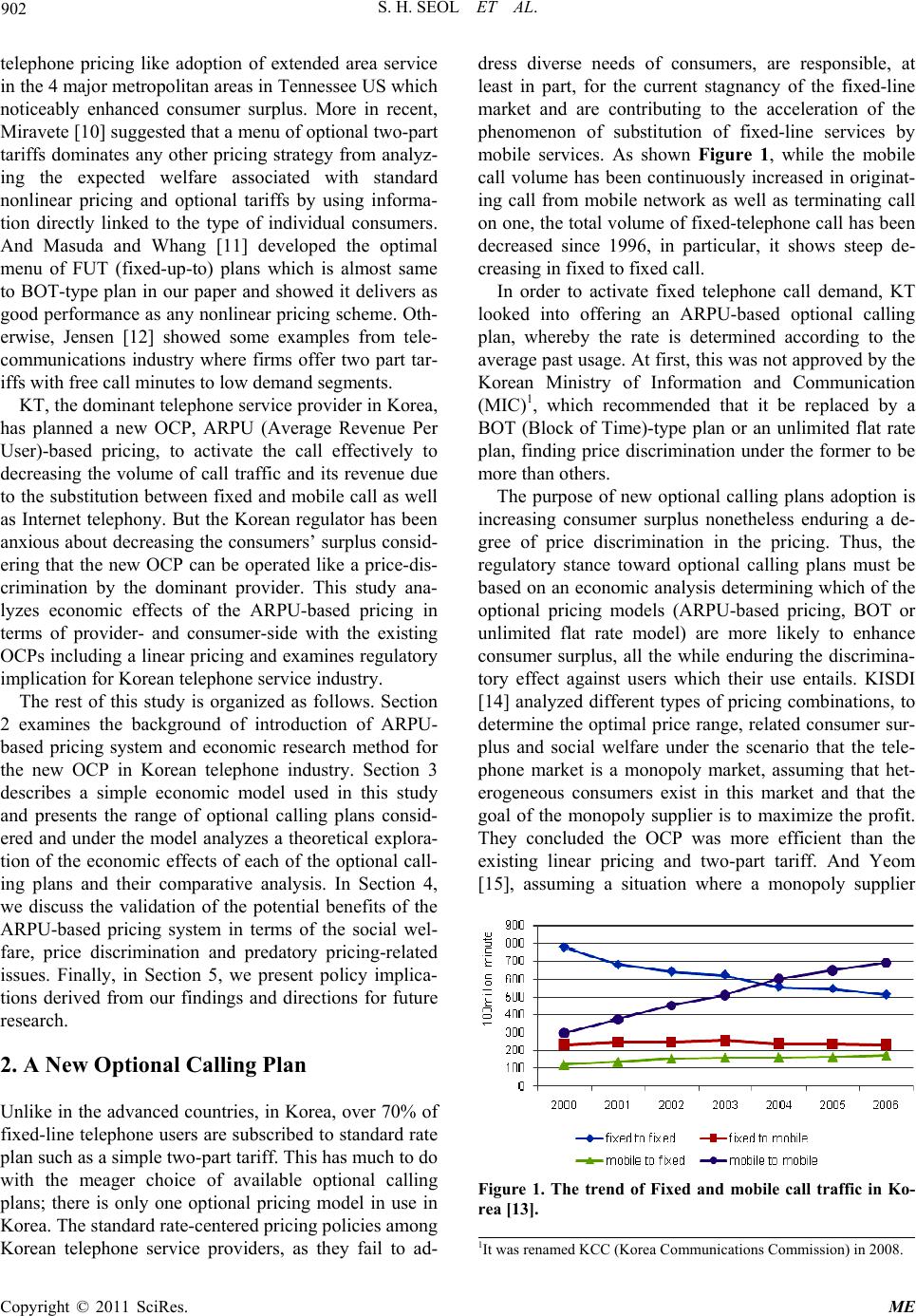

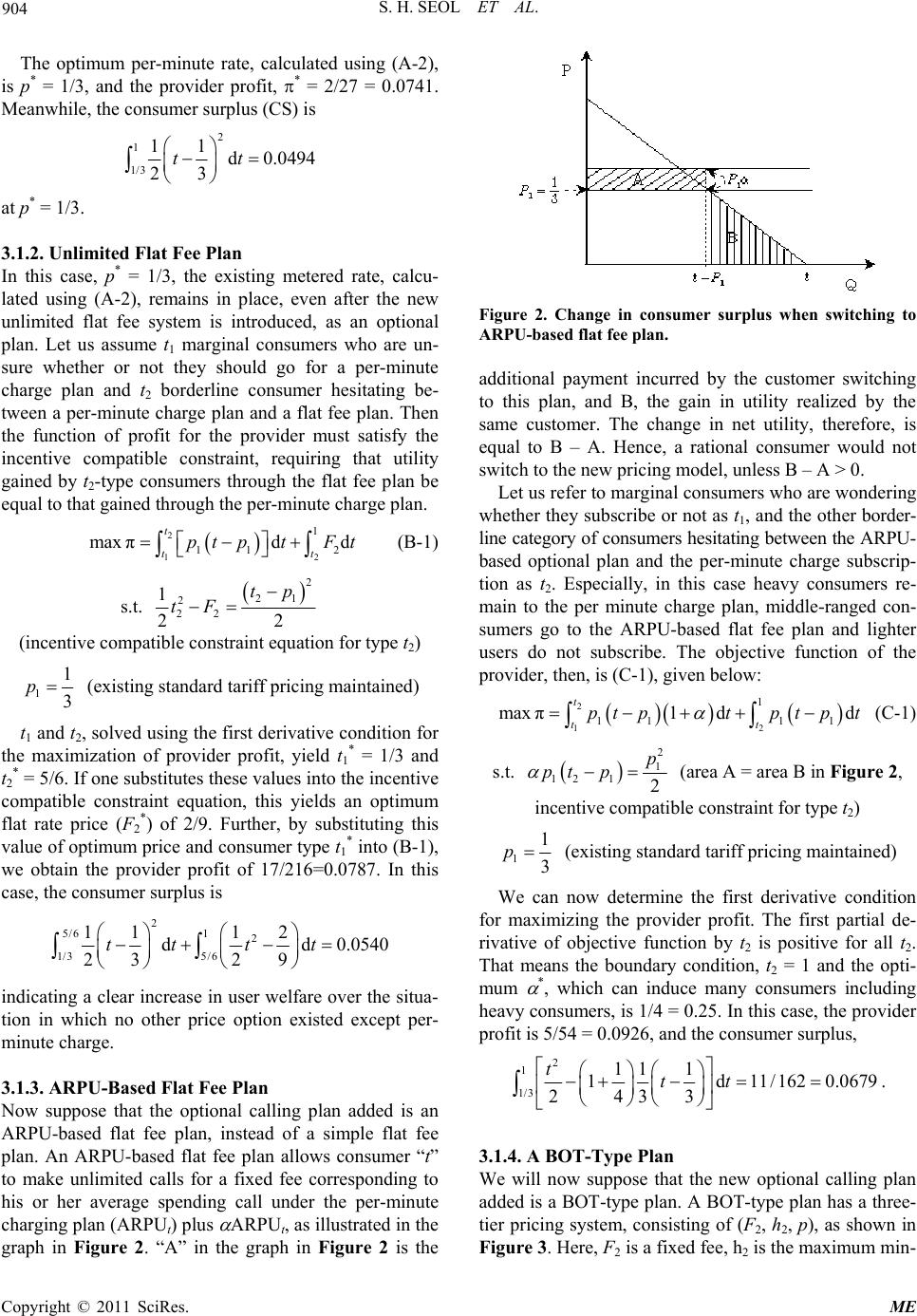

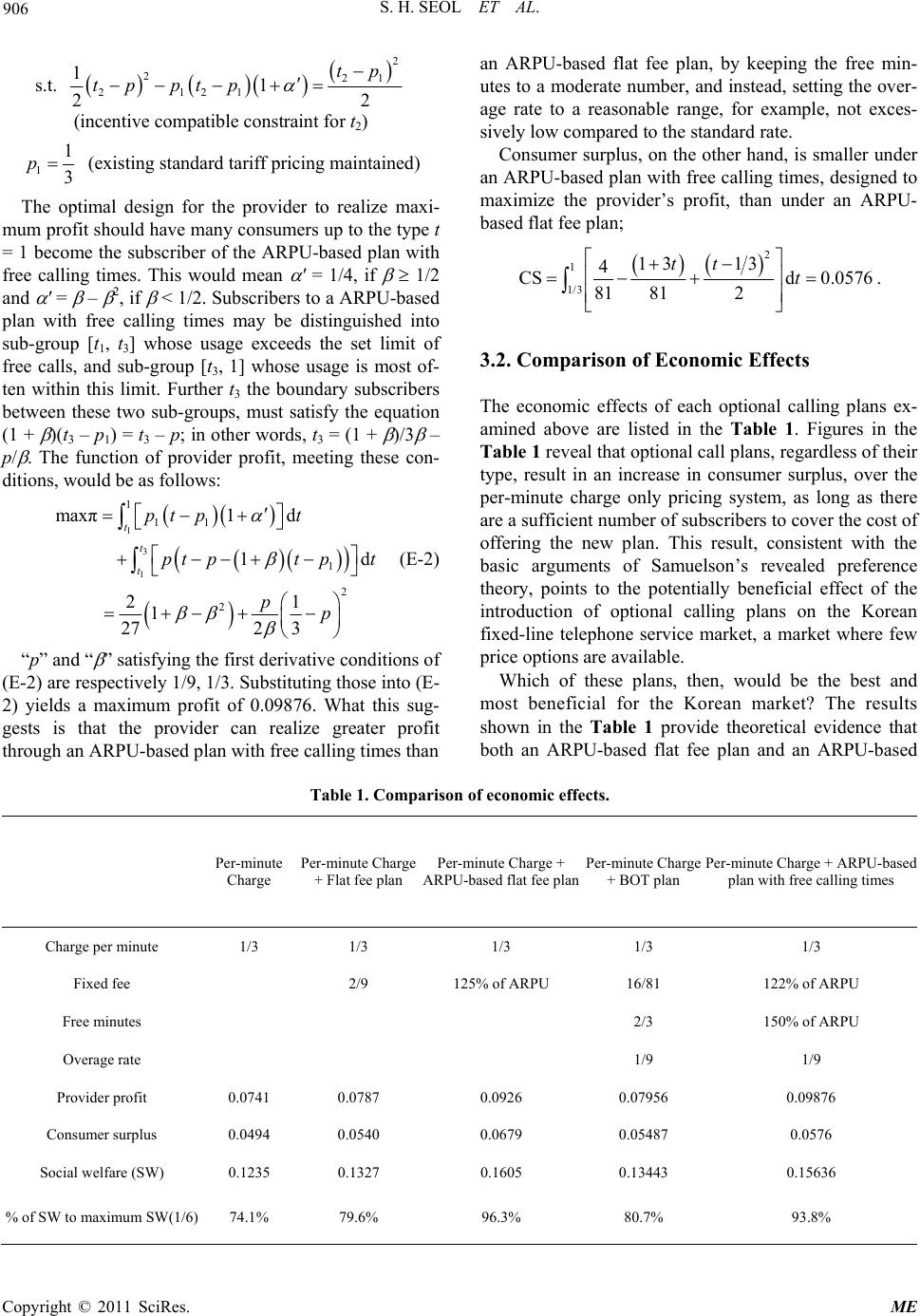

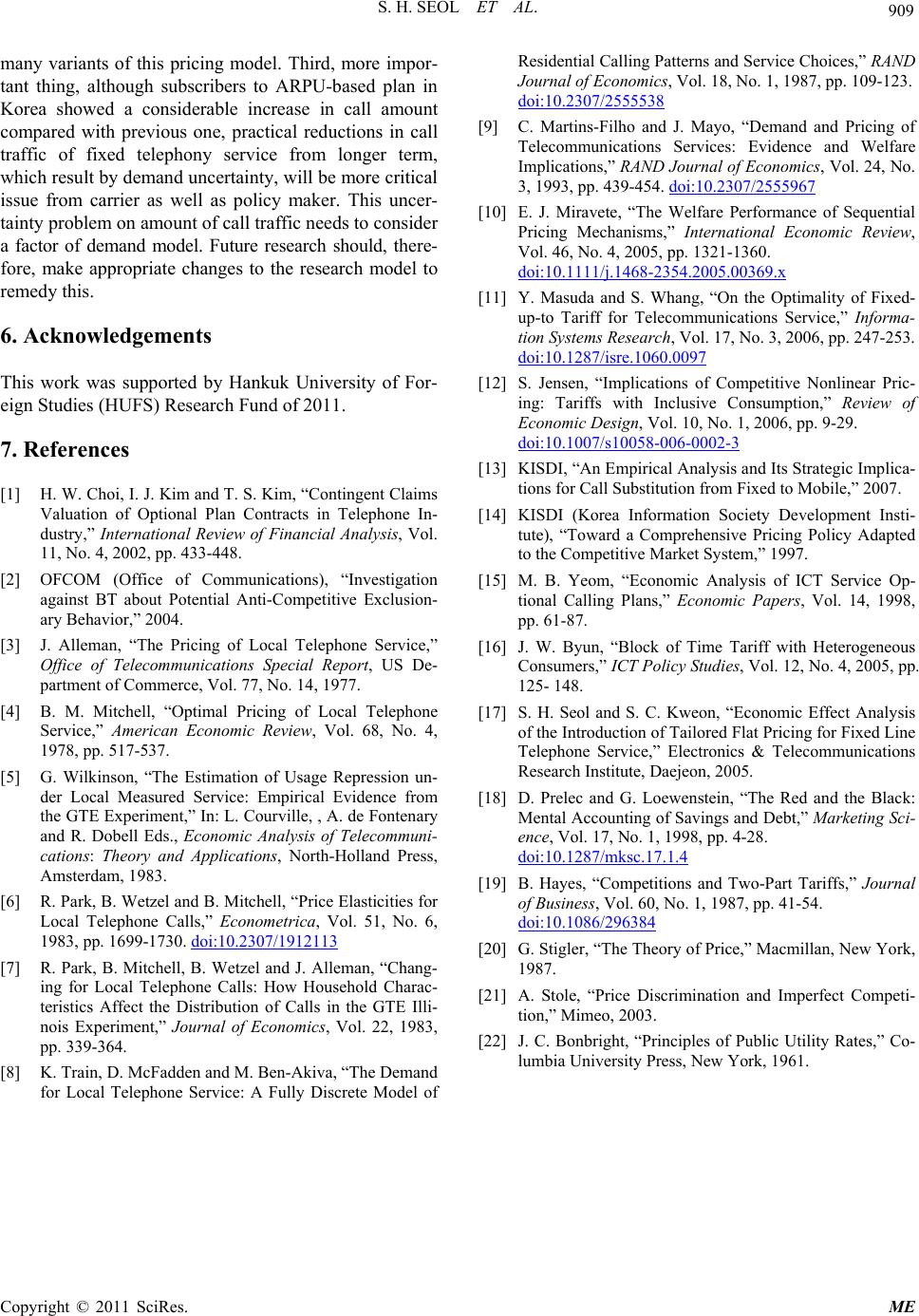

|