Vol.2, No.4, 424-431 (2011) doi:10.4236/as.2011.24054 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ Agricultural Scienc es Influence of agronomic variables on quality of tomato fruits Marcos Hernández Suárez1, Eladia Peña Méndez2, Beatriz Rodríguez Galdón3, Elena Rodríguez Rodríguez2, Carlos Díaz Romero2* 1Agriculture Technology National Centre “Extremadura” CTAEX, Villafranco del Guadiana, Badajoz, Spain; 2Analytical Chemistry, Nutrition and Food Science Department, La Laguna University, La Laguna, Spain; *Corresponding Aut hor: cdiaz@ull.es 3Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Department, Extremadura University, Badajoz, Spain. Received 4 August 2011; revised 18 September 2011; accepted 11 October 2011. ABSTRACT In order to study interactions between agro- nomic variables and chemical composition that determine the quality of tomato fr uit s, a group of statistical techniques were applied: discriminant analysis (DA), cluster analysis (CA) and prince- pal component analysis (PCA) combined with ANOVA. The results of DA when characterizing the agronomic parameters were successful, es- pecially when the collection date was used as a factor for classification. CA showed the impor- tance of the chemical variables related to the metabolic relationships, w hile the principal com- ponent analysis and ANOV A provide information on the interaction between variables related to the production and chemical composition of tomatoes. The combined use of PCA and ANOVA is a suitable tool for studying the complex in- teractions between agronomy and chemical composition. Collection date was the main ag- ronomic parameter effected the chemical com- position, while variety and production system had a minor effect. The application of PCA- ANOVA showed that the taste of tomato de- pends on three factors: sugars (glucose and fructose), acidity (citric, malic and ascobirc acids), an d mine ral s (Na and Mg). F or the tom a- toes with same maturity degree, the taste de- pends on interaction of date collection and system production. Keywords: Tomato; Chemical Composition; Agronomy; Multivariate Analysis 1. INTRODUCTION The tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) is not only one of the world’s most important vegetables, but it is also the most widely used as well as being a versatile vegetable crop. They are consumed fresh and are also used to manufacture a wide range of processed products. These are some of the reasons why the scientific community has recently become interested in the tomato [1]. It is an excellent source of the following nutrients and second- dary metabolites which are important for human health: minerals, vitamins C and E, β-carotene, lycopene, fla- vonoids, organic acids, phenolics and chloroph yll [2-4]. In the case of plant foods, fruit ripening is a geneti- cally programmed process culminating in changes in color, texture, flavor, and chemical compositions [5]. As a result, the chemical composition of the tomato fruit depends on factors such as cultivar, maturity and the environmental conditions in which they are grown [6-8]. Foodstuffs are a physico-chemical complex matrix of several interacting factors. A complete understanding of the complex interactions between environment, metabo- lism, and chemical composition of crops would require the input of information fro m a multidiscip lin ary team of scientists and the use of tools to in terpret those relations, by example multivariate analysis [9]. In previous reports [10-13], the chemical composition of the tomato has been widely described according to several agronomic variables such as variety, date of col- lection, cultivation area and production system. The aim of this work is to characterize and unravel the relation- ship between agronomy and chemical composition of tomatoes by using the combination of several chemom- etric tools. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Samples One hundred and sixty seven samples, belonging to five cultivars of tomatoes (Dorothy, Boludo, Thomas, Dominique, Dunkan), were provided by ACETO (Aso-  M. H. Suárez et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 424- 431 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 425425 ciación Provincial de Cosecheros Exportadores de To- mates de Tenerife) and other companies from different farms located in the southern and western regions of the island of Tenerife (Spain). Four samples (1 kg of weight) of each of the five cultivars were collected during dif- ferent periods. Agronomic parameters such as variety, production system, date of collection and cultivation area were considered (Tab le 1). Additional information relating to the tomato samples can be found in previous research [10-13]. 2.2. Analytical Methods Three tomatoes selected from each sample were hand-rinsed with ultrapure water, shaken to remove any excess water and gently blotted with a paper towel. The tomatoes were then mixed and homogenised to a homo- geneous puree using a model T-25 Basic Turmix (Ika- Werke, Staufen, Germany). The puree was stored in a polyethylene tube at –80˚C. Several sub-samples were taken in duplicate from this puree to measure the differ- ent parameters. Moisture content was determined by drying the sam- ples to a constant weight at 105˚C according to AOAC [14]. Ash content was measured by calcinations at 550˚C to a constant weight, according to AOAC [14]. Nitrogen content was determined according to the Kjeldahl method and nitrogen value was multiplied by 6.25 as conversion factor [14]. Total fibre was determined ac- cording to the method proposed by Prosky et al. [15]. Ascorbic acid was determined by the 2,6-dichlorophe- nol-indophenol titration procedure [14]. The acidity was determined by means of titration with NaOH 0.1 mol/L until pH 8.1, expressing the results in grams of anhy- drous citric acid per 100 g. The pH was determined by potenciometric measurement at T = 20˚C with a pH- meter [14]. The content of total phenolics was deter- mined according to the Folin-Ciocalteu method [16]. Lycopene concentration was determined spectropho- tometrically [17]. The mineral content was determined by atomic ab- sorption spectrophotometry previous to nitric digestion [11], except for phosphorous which was measured by a colorimetric method, using the Vanadate-Molybdate re- agent [18]. The analytical HPLC methods were used to measure the contents of sugars were proposed by Li et al. [19] and modified by Hernández et al. [12]. The analyti- cal method used to measure the content of organic acids was proposed by Hernández et al. [13]. Hydroxycin- namic acids were determined according the methos pro- posed by Martínez-Valverde et al. [20] and modified by Hernández et al. [10]. 2.3. Statistical Analysis All the statistics were performed by means of the SPSS version 17.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). Each quantitative variable was standard- ized according to a typical z-standarization. A linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was applied on chemical composition to classify the tomato samples according to the agronomical parameters such as variety, production system, date of collection and the cultivation area. The variables used for the classification of tomato samples Stepwise LDA was applied using Wilk’s lambda and F-statistic as the selection criterion for the quantita- tive variables, thereby enhancing the discrimination be- tween established groups. Cluster analysis (CA) is one of the most useful chemo- metric tools for studying the classification tendency of the samples. Moreover, CA was applied to find out the underlying relationships between the chemical parame- ters used in this study. Among several clustering algo- rithms, Ward’s method was selected as the linkage method using Euclidean distance as the measure of similarity. Table 1. Distribution of the tomato samples analyzed according to cultivar, cultivation method, sampling period, and region of pro- duction. Production system Date of collection Cultivation area* Variety Total Intensive Organic HydroponicOct 04-Nov 04Dec 04-Jan 05Feb 05-Mar 05Apr 05-Jun 05 WestSouth Dorothy 50 25 14 11 14 16 12 8 16 9 Boludo 46 28 14 4 12 12 11 11 15 13 Dominique 19 10 9 0 4 8 5 2 0 0 Thomas 25 16 9 0 8 8 4 5 0 0 Dunkan 27 4 12 11 2 10 9 6 0 0 Overall 167 83 58 26 40 54 41 32 31 22 *Only in intensive cultivation.  M. H. Suárez et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 424- 431 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 426 Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to explore the complex relationships/connections between the parameters regarding the agronomical uses and the chemical composition. One way ANOVA was performed to investigate which agronomical parameters influence each principal component (PC) and clarify the results obtained. 3. RESULTS AND DIS CUSSION Some scientists suggest that multivariate analysis should be performed with those independent variables without a clear relationship between them [21]. In a pre- vious papers [10-13], we reported that pH, acidity and ash depend on other analyzed variables, organic acids and minerals respectively. Besides, in this moisture showed an inverse relationship with the rest of the vari- able studied due to the fact that an increase in water content reduces the concentration of other parameters [10-13]; these facts are consistent with data from other authors [22]. Therefore, the variables moisture, ash, pH, and acidity were not consid ered in this paper. 3.1. Characterization of Agronomic Variables by LDA When the tomato variety is used as the criterion for classification, a very low classification, 32.3% (27.5% after cross-validation) was obtained and the selected variables in this stepwise-LDA were Fe, glucose and ferulic acid. This percentage of classification suggests that the chemical parameters analyzed were not good enough to characterize the varieties. Alth ough the results appear to contradict other studies that report a change in chemical composition with the tomato variety [7,8,20], in our case the variety has a limited influence on the chemical composition. This could be attributed to dif- ferences in the ripening stage of tomatoes belonging to different varieties, although, in this work, tomato sam- ples did not show significant difference between each other regarding the maturity index [12]. Tomatoes undergo a wide range of biosynthetic as well as degradative reactions that markedly affect the final chemical composition of the fruit during ripening [23]. These changes are highly coordinated and modified by genetic and environmental factors. This aspect is impor- tant because the consumer chooses the tomatoes for their appearance (color, size, shape, freedom from physio- logical disorders, and decay), firmness, texture, dry mat- ter, and organoleptic (flavor) and health properties [24]. In the case of the date of collection as th e criterion for classification, a high percentage of classification (91.6%, 89.8% after cross-validation) was observed when select- ing the following variables: glucose, lycopene, and py- ruvic, malic, citric, fumaric, and p-c ou maric acids, Na, K, Mg, P, and Ca. Figure 1 presents the classification of the tomato samples on the two firsts discriminant functions. This percentage of classification suggests that the physi- co-chemical matrix of data selected can be used to char- acterize the tomatoes according to the date of collection satisfactorily (Figure 1). An analysis of the results shows the relationship of the variables selected in the stepwise-LDA with temperature. The synthesis of glu- cose (photosynthesis) and organic acids (pyruvic, malic, citric and fumaric) of the Krebs cycle are regulated by the temperature [25], and lycopene synthesis is com- pletely inhibited at 32˚C and temperatures higher than 30˚C - 35˚C notably reduced the lycopene content [26]. Adverse environmental conditions can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cherry tomato fruits, which attack all types of biomolecules, causing several altera- tions in the fruit [26-28]. This could explain why lyco- pene and p-coumaric acids, both antioxidants, were se- lected to characterize the date of collection. As regards the minerals, the deficiency of Ca in the tissues can cause physiological disorders. Besides which, salinization also limits the absorption of Ca. Both proc- esses involve a regulation of ion concentrations (Ca, Na and K), especially in the summer [29,30]. When the production system was the criterion of clas- sification, a low percentage of classification, 69.3% (63.9% after cross-validation) was obtained after select- ing the following variables: glucose, lycopene, P, Na, Mg, Mn, and total fibre. Therefore, no clear relationship Figure 1. Scores plot of tomato samples according to the date of collection on the space of two first discriminant functions.  M. H. Suárez et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 424- 431 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 427427 between the quantitative variables with the production system was found. Few studies have shown that there are no differences in the physico-chemical and sensory qual- ity of conventional tomatoes grown in soil or in rock- wool slabs (a kind of hydroponic culture) [31]. However, it has been shown that organic foods seem to have higher levels of vitamin C, certain essential minerals (Ca, Mg, Fe) and phytochemicals such as lycopene in tomatoes, polyphenols in potatoes or flavonols in apples [31-33 ]. Organic tomatoes contained more salicylic acid but less vitamin C and lycopene when compared to crops grown using conventional and organic methods [31,34, 35]. Organic fruits had a slightly higher protein content than conventionally cultivated fruits, perhaps because the plants were grown und er stressful conditions [36,3 7]. Cultivation area was considered as the fourth factor for classification. Only intensively cultivated Dorothy and Boludo varieties were considered in this case. The following variables: pyruvic acid, ascorbic acid, total fibre, Na, Ca, Mg, and Mn were selected and gave a high percentage of classification, 92.3% (90.8% after cross- validation). The good results suggest that when the pro- duction system is homogeneous, the differences between tomatoes varieties grown in different areas could mainly be due to the mineral composition of soils as well as to climatic factors. Low levels of Ca in soil may influence the content of total fibre in tomatoes [38]. The presence of ascorbic acid in the selected variables could be ex- plained by two reasons: firstly because Na increases ascorbic acid in the tomato fruit [36], and secondly be- cause light exposure is favourable to vitamin C accumu- lation [26,39]. Metabolic relationships could explain the presence of Mg, Mn and pyruvic acid. Mg active en- zymes such as phosphoenol pyruvate carboxylase and Mn are involved in photosynthesis [25]. 3.2. Characterization of Chemical Composition by CA Figure 2 presents the dendrogram obtained using Ward’s linkage method (Euclidean distance). Five main groups were considered: A, B, C, D and E, where there are several subgroups withi n each group. Group A included two subgroups, sugars (fructose and glucose) and certain organic acids (malic, citric,and fu- maric acids). These variables are associated with or- ganoleptic properties which are mainly attrib uted to their aroma compounds, sugars, and organic acid contents [31]. Glucose and fructose account for about 95% of the total sugars in the tomato whereas sucrose is detected in trace amounts [40,41]. The rest of groups are linked to the nu tritional quality. Worthington [31] defined nutritional quality o f a fruit for the content in minerals, vitamins, and bioactive com- pounds such as carotenoid and flavonoid contents. Group B included chemical parameters essential for good plant development. A first subgroup: oxalic and pyruvic acids; and a second subgroup with protein and Fe. Pyruvic and oxalic acids are precursors of the Krebs cycle and Fe is the main micronutrient, often linked to proteins or enzymes [25]. Figure 2. Dendrogram obtained by cluster analysis of variables using Ward’s method of linkage.  M. H. Suárez et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 424- 431 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 428 The several subgroups of parameters included within group C have clear relationships between them. The availability of Mg depends on K concentration and both minerals are involved in the synthesis of carotenoid compounds [42]. Salt enrichment (Na) in the nutrient solution of plants is known to increase the ascorbic acid content, which adds acidic taste to the fruit [43]. As re- gards phenolic compounds, although genetic control is the main factor in determining their accumulation in vegetable foods, external factors may also have a sig- nificant effect on this. In many plant species the flavonol content may be enhanced in response to elevated light levels, in particular to increased UV-B radiation and the level of P. Tomato plants grown under high light accu- mulate a higher soluble phenol content (rutin and chloro- genic acid) than low-light plants [44-47]. Chemical parameters related with structural function appear in group D. Ca plays an essential role in this process by preserving the structural and functional in- tegrity of plant membranes, stabilizing cell wall struc- tures and regulating ion transport [48,49]. Group E consisted of the main antioxidants, such as hydroxycinnamic acids and lycopene, and of Cu. The data available on the effect of mineral nutrients on the antioxidant compounds of tomato are either scarce or not very reliable or appl icabl e [26 ] . 3.3. Characterization of Agronomic Variables and Chemical Composition by PCA After performing PCA analysis, 71.3% of the variance could be explained by eight main components having eigenvalues higher than 1. Table 2 shows the first six PCs for the characterization of tomatoes. The chemical variables had low loads on PC7 and PC8, and therefore, they are not shown. The last column of Tab l e 2 shows the result of one way ANOVA on each PC. Figure 3 shows the loading p lot of the considered variables in the PCA projected on the plane of PC1 vs PC2. Table 2. Results of PCA without rotation. Total variance explained: 71.3%. PC % variance Main quantitative variables included Agronomic parameters that influences in the PC§ PC1 16.4 Glucose, fructose, malic acid, citric acid, ascorbic acid, Na, Mg* Date of collection, production system, cultivation area† PC2 13.3 Lycopene, oxalic acid, protein, Zn, Fe, Cu Date of collection, cultivation area† PC3 11.1 p-Coumaric acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, Ca, Mn, P Date of collection, production system, cultivation area† PC4 9.1 Total fibre, pyruvic acid, chlorogenic acid Production system PC5 7.1 K, Mg* Date of collection, production system PC6 5.8 Phenolic compounds, fumaric acid Variety *The PCA included the Mg in two PCs, 1 and 5, with similar load; §ANOVA on each PC (P < 0.05); †Only for the intensive Dorothy and Boludo varieties. Figure 3. Loading plot of Principal Components Analysis (PCA) projected on the space of PC1 vs PC2.  M. H. Suárez et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 424- 431 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 429429 PC1 explains 16.4% of the variance and is formed by the chemical variables that define the organoleptic prop- erties of the tomato (Table 2): sugars (glucose and fruc- tose), the main organic acids (malic, citric and ascorbic acids) and the minerals Na and Mg together (Mg is also included in PC5). Date of collection, production system and the cultivation area are the agronomic variables which influence this PC. As has already been mentioned, the organic acids are related with organoleptic properties and they contribute to increasing ascorbic acid as well as adding acidic taste to the fruit [36]. PC2 explains 13.3% of the variance and groups the following variables together: lycopene, oxalic acid, pro- tein, Zn, Fe and Cu. This PC contains variables directly influenced by date of collection and the cultivation area and suggests a metabolic relationship that depends on the environmental conditions. The synthesis of lycopene is influenced by temperature [26]. Therefore, the synthe- sis of this carotenoid starts at temperatures above 16˚C, is optimal at 22˚C - 25˚C and decreases from 30˚C [26]. Furthermore, the accumulation of lycopene blocks radia- tion with values greater than 650 W/m2 thereby affecting the homogeneous red color of the fruit [23]. With respect to the proteins, plants grown under stressful conditions may provide a storage form of nitrogen that is re-utilized when the stress is over, the protein may also be synthe- sized in response to salt stress, such as happens in crop fertilization [48,49]. The presence of Zn, Fe and Cu in this PC may be due to a metal-protein association, such as the synthesis of isoenzymes of superoxide dismutase linked to Zn and Cu which is a vegetable defense me- chanism [25]. Hydroxycinnamic acids (p-coumaric, caffeic and fer- ulic acids) and the minerals Ca and P and the trace ele- ment, Mn, are associated to PC3. This PC could be asso- ciated to antioxidant activity and to some minerals. Plants synthesize antioxidant compounds such as the hydroxyl- cinnamic acid (p-coumaric, caffeic and ferulic acids) which frequently occur in foods as simple esters with quinic acid or glucose, as well as flavonoids and phenol- lic compounds to prevent oxidation reactions [50]. Fla- vonoids and pheno lic acids are componen ts der ived fr om the route of the pentose phosphate, which is involved in maintaining and providing antioxidant defense functions and they may accumulate because of a deficiency of N, P and Fe [51]. The presence of P in this PC could be ex- plained by the fact that an appropriate level of P is cru- cial not only for normal growth and development of the plant, but also for the synthesis of various secondary metabolites [47]. Mn participates in the electron trans- port of photosynthesis and Ca is a structural element of the membrane through which the exchange of electrons takes place [25]. PC4 groups the following variables together: total fi- bre, pyruvic acid and chlorogenic acid. The percentage of variance explained was 9.1% and the production sys- tem was the agronomic variable associated to this PC. PC5 explains 7.1% of variance, the variables associated were K and Mg; which depend on date of collection and production system. PC6 is the only PC that depends on variety. It groups phenolic compounds and fumaric acid together and it explains only 5.8% of the variance. Each of the remaining PCs should be formed by at least 4 variables in order to interpret their meaning cor- rectly [21]. An intuitive interpretation could be taken from reviews in the literature. Thus, PC5 is formed by K and Mg which are related with the synthesis of carote- noids and pigments. The application of K fertilizers, especially lycopene, can increase the carotenoid conten ts in tomatoes and Mg is a component of chlorophyll [26, 52]. Note that PC6 is the only principal component where variety is the variable with the greatest load. Some authors have used the metabolic compounds asso- ciated to the second metabolites, as a quick classification of samples according to their origin or biological prove- nance [53]. 4. CONCLUSIONS Multivariate statistical analysis is a suitable tool for the evaluation of extensive data tables but in some cases it is essential the combination of several techniques to obtain good results. The application of PCA-ANOVA was an effective tool to analyze the chemical composi- tion of tomato and to know the agronomic variables that influence the composition. For the same maturity, the organoleptic quality of tomato expressed as the sugar content, organic acids and mineral content (Na) only depends on interaction of production system and date of collection. REFERENCES [1] Giovanelli, G. and Paradiso, A. (2002) Stability of dried and intermediate moisture tomato pulp during storage. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 50, 7277- 7281. doi:10.1021/jf025595r [2] Madhavi, D.L. and Salunkhe, D.K. (1998) Production, composition, storage, and processing. New York. [3] Lavelli, V., Peri, C. and Rizzolo, A. (2000) Antioxidant activity of tomato products as studied by model reactions using xanthine oxidase, myeloperoxidase, and copper- induced lipid peroxidation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 48, 1442-1448. doi:10.1021/jf990782j [4] Leonardi, C., Ambrosino, P., Esposito, F. and Fogliano, V. (2000) Antioxidative activity and carotenoid and to- matine contents in different typologies of fresh con- sumption tomatoes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 48, 4723-4727. doi:10.1021/jf000225t  M. H. Suárez et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 424- 431 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 430 [5] Giovanelli, G., Lavelli, V., Peri, C. and Nobili, S. (1999) Variation in antioxidant components of tomato during vine and post-harvest ripening. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 79, 1583-1588. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199909)79:12<1583::AID -JSFA405>3.0.CO;2-J [6] Van Boekl, M. and Jongen, W.M. (1997) Product quality and food processing: How to quantify the healthiness of a product. Cancer Letters, 114, 65-69. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(97)04627-2 [7] Abushita, A.A, Daood, H.G. and Biacs, P.A. (2000) Change in carotenoids and antioxidants vitamins in to- mato as a functional of varietal and technological factors. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 48, 2075- 2081. doi:10.1021/jf990715p [8] Thompson, K.A., Marshall, M.R., Sims, C.A., Wei, C.I., Sargent, S.A. and Scott, J.W. (2000) Cultivar, maturity and heat treatment on lycopene content in tomatoes. Journal of Food Science, 65, 791-795. doi:10.1111/j. 13 65-2621.2000.tb13588.x [9] Grattan, S.R. and Grieve, C.M. (1999) Salinity—Min- eral nutrient relations in horticultural crops. Scientia Horticulturae, 78, 127-157. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(98)00192-7 [10] Hernández, M., Rodríguez, E. and Díaz, C. (2007a) Free hydr oxycin namic a cids, lycope ne and color paramet ers i n tomato cultivars. Journal of Agricultural and Food Che- mistry, 55, 8604-8615. doi:10.1021/jf071069u [11] Hernández, M., Rodríguez, E.M. and Díaz, C. (2007b) Mineral and trace element concentrations in cultivars of tomatoes. Food Chemistry, 104, 489-499. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.11.072 [12] Hernández, M., Rodríguez, E.M. and Díaz, C. (2008b). Chemical c omposi tion of tomat o (Lycopersi con es c ulen tum ) from Tenerife, the Canary Islands. Food Chemistry, 106, 1046-1056. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.07.025 [13] Hernández, M., Rodríguez, E. and Díaz, C. (2008a) Analysis of organic acid content in cultivars of tomato harvested in Tenerife. European Food Research and Technology, 226, 423-435. doi:10.1007/s00217-006-0553-0 [14] AOAC (1999) Food composition; additives; natural con- taminants. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC, 2, AOAC, Arlington. [15] Prosky, L., Asp, N., Furda, I., De Vries, J., Schweizer, T. and Harland, B. (1985) Determination of total dietary fi- ber in foods and food products: Collaborative study. Journal of Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 68, 677-679. [16] Kujala, T.S., Loponen, J.M., Klika, K.D. and Pihlaja, K. (2000) Phenolic and betacyanins in red beetroot (Beta vulgaris) root: Distribution and effect of cold storage on the content of total phenolic and three individual com- pounds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 48, 5338-5342. doi:10.1021/jf000523q [17] Fish, W., Perkins-Veazie, P. and Collins, J. (2002) A quantitative assay for lycopene that utilizes reduced volumes of organic solvents. Journal of Food Composi- tion and Analysis, 15, 309-317. doi:10.1006/jfca.2002.1069 [18] BOE (1995) Boletín Oficial del Estado. R.D. 2257/1994, de 25 de noviembre, por el que se aprueban los métodos oficiales de piensos o alimentos para animales y sus materias primas. No. 52 de 2 de marzo de 1995, 7161- 7235. [19] Li, B.W., Andrews, K.W. and Pehrsson, P. R. (2002) Indi- vidual sugars, soluble, and insoluble dietary fiber con- tents of 70 high consumption foods. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 15, 715-723. doi:10.1006/jfca.2002.1096 [20] Martínez-Valverde, I., Periago, M., Provan, G. and Ches- son, A. (2002) Phenolic compounds, lycopene and anti- oxidant activity in commercial varieties of tomato (Ly- copersicon esculentum). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 82, 323-330. doi:10.1002/jsfa.1035 [21] Díaz, V. (2002) Técnicas de análisis multivariante para investigación social y comercial. Ejemplos Prácticos Utilizando SPSS, Versión 11, Madrid. [22] Nielsen, S. (2003) Food analysis. 3rd Edition, Kluwer Academic, New York. [23] Giuntini, D., Graziani, G., Lercari, B., Fogliano, V., Soldatini, G.F. and Ranieri, A. (2005) Changes in carote- noid and ascorbic acid contents in fruits of different to- mato genotypes related to the depletion of UV-B radia- tion. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 53, 3174-3181. doi:10.1021/jf0401726 [24] Grierson, D. and Kader, A.A. (1986) The tomato crop, a scientific basis for improvement. Springer, London. [25] Azcón-Bieto, J. and Talon, M. (2008) Fundamentos de fisiología y bioquímica vegetal. Interamericana McGraw- Hill, Madrid. [26] Dumas, Y., Dadomo, M., Di Lucca, G. and Grolier, P. (2003) Effects of environmental factors and agricultural techniques on antioxidant content of tomatoes. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 83, 369-382. doi:10.1002/jsfa.1370 [27] Adams, S.R., Cockshull, K.E. and Cave, C.R.J. (2001) Effect of temperature on the growth and development of tomato fruits. Annals of Botany, 88, 869-877. doi:10.1006/anbo.2001.1524 [28] Rosales, M.A., Cervilla, L.M., Ríos, J.J., Blasco, B., Sánchez-Rodríguez, E., Romero, L. and Ruiz, J.M. (2009) Environmental conditions affect pectin solubilization in cherry tomato fruits grown in two experimental Mediter- ranean greenhouses. Environmental and experimental botany, 67, 320-327. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.07.011 [29] Cuartero, J. and Fernández-Muñoz, R. (1999) Tomato and salinity. Scientia Horticulturae, 78, 83-125. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(98)00191-5 [30] Bertin, N., Guichard, S., Leonardi, C., Longuenesse, J.J., Langlois, D. and Navez, B. (2000) Seasonal evolution of the quality of fresh glasshouse tomatoes under Mediter- ranean conditions, as affected by air vapour pressure deficit and plant fruit load. Annals of Botany, 85, 741- 750. doi:10.1006/anbo.2000.1123 [31] Worthington, V. (2001) Nutritional quality of organic versus conventional fruits, vegetables, and grains. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 7, 61-173. doi:10.1089/107555301750164244 [32] Magkos, F., Arvaniti, F. and Zampelas, A. (2003) Or- ganic food or food for thought? A review of the evidence. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 54,  M. H. Suárez et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 424- 431 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/Openly accessible at 431431 357-371. doi:10.1080/09637480120092071 [33] Thybo, A.K., Edelenbos, M., Christensen, L.P., Sørensen, J.N. and Thorup-Kristensen, K. (2006) Effect of organic growing systems on sensory quality and chemical com- position of tomatoes. LWT—Food Science and Technol- ogy, 39, 835-843. [34] Jin, S., Chen, C.C. and Plant, A.L. (2000) Regulation by ABA of osmotic-stress-induced changes in protein syn- thesis in tomato roots. Plant, Cell and Environment, 23, 51-60. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2000.00520.x [35] Senaratna, T., Touchell, D., Bumm, E. and Sixon, K. (2000) Acetyl salicylic (Aspirin) and salicylic acid in- duce multiple stress tolerance in bean tomato plants. The Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 30, 157-161. doi:10.1023/A:1006386800974 [36] Pastori, G.M. and Foyer, C.H. (2002) Common compo- nents, networks, and pathways of cross-tolerance to stress. The central role of “redox” and abscisic acid-me- diated controls. Plant Physiology, 129, 7460-7468. [37] Rossi, F., Godani, F., Bertuzzi, T., Trevisan, M., Ferrari, F. and Gatti, S. (2008). Health promoting substances and heavy metal content in tomatoes grown with different farming techniques. European Journal of Clinical Nutri- tion, 47, 266-272. doi:10.1007/s00394-008-0721-z [38] Poovaiah, B.W., Glenn, G.M. and Reddy, A.S.N. (1988) Calcium and fruit softening: Physiology and biochemis- try. Horticultural Reviews, 10, 107-152. [39] Lee, S.K. and Kader, A.A. (2000) Preharvest and post- harvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horti- cultural crops. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 20, 207-220. doi:10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00133-2 [40] Haila, K., Kumpulainen, J., Hakkinen, U. and Tahvonen, R. (1992) Sugar and organic acid contents of vegetables consumed in Finland during 1988-1989. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 5, 100-107. doi:10.1016/0889-1575(92)90024-E [41] Young, T.E., Juvik, J.A. and Sullivan, J.G. (1993) Accu- mulation of the components of total solids in ripening fruits of tomato. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 118, 286-292. [42] Chapagain, B.P. and Wiesman, Z. (2004) Effect of potas- sium magnesium chloride in the fertigation solution as partial source of potassium on growth, yield and quality of greenhouse tomato. Scientia Horticulturae, 99, 279- 288. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(03)00109-2 [43] Zushi, K. and Matsuzoe, N. (1998) Effect of soil water deficit vitamin C, sugar, organic acid, amino acid and carotene contents of large-fruited tomatoes. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science, 67, 927- 933. doi:10.2503/jjshs.67.927 [44] Macheix, J.J., Fleuriet, A. and Billot, J. (1990). Fruit phenolics. CRC Press, Boca Raton. [45] Brandt, K., Giannini, A. and Lercari, B. (1995) Pho- tomorphogenic responses to UV radiation III: A com- parative study of UVB effects on anthocyanin and fla- vonoid accumulation in wild type and aurea mutant of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Photochemistry and Photobiology, 62, 1081-1087. doi:10.1111/j. 17 51-1097.1995.tb02412.x [46] Wilkens, R.T., Spoerke, J.M. and Stamp, N.E. (1996) Differential responses of growth and two soluble pheno- lics of tomato to resource availability. Ecology, 77, 247- 258. doi:10.2307/2265674 [47] Raghothama, K.G. (1999) Phosphate acquisition. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology, 50, 665-693. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.665 [48] Asami, D.K., Hong, Y.J., Barrett, D.M. and Mitchell, A.E. (2003) Comparison of the total phenolic and ascorbic acid content of freeze-dried and air-dried marionberry, strawberry, and corn using conventional, organic, and sustainable agricultural practices. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 51, 1237-1241. doi:10.1021/jf020635c [49] Ashraf, M. and Harris, P. (2004). Potential biochemical indicators of salinity tolerance in plants. Plant Science, 166, 3-16. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2003.10.024 [50] Matilla, P. and Kumpulainen, J. (2002). Determination of free and total phenolic acid in plant-derived foods by HPLC with diode-array detection. Journal of Agricul- tural and Food Chemistry, 50, 3660-3667. doi:10.1021/jf020028p [51] Dixon, R.A. and Paiva, N.L. (1995). Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell, 7, 1085-1097. [52] Trudel, M.J. and Ozbun, J.L. (1971). Influence of potas- sium on carotenoid content of tomato fruit. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 96, 763-765. [53] Fiehn, O. (2001). Combining genomics, metabolome ana l y - sis, and biochemical modelling to understand metabolic networks. Comparative and Functional Genomics, 2, 155-168. doi:10.1002/cfg.82 LEGEND Cou: p-coumaric acid, Cu: copper, Lyc: lycopene, Zn: zinc, Mn: manganese; Fer: ferulic acid, Caf: caffeic acid, P: phosphorus, Pyr: pyruvic acid, Oxa: oxalic acid, Pro: protein, Fe: iron, Fum: fumaric acid, Cit: citric acid, Fru: fructose, Glu: glucose, Mal: malic acid, AA: ascorbic acid, TF: total fibre, Phe: phenolic compounds, Mg: magnesium, Na: sodium, Chlo, chlorogenic acid, K: po- tassium, Ca: calcium

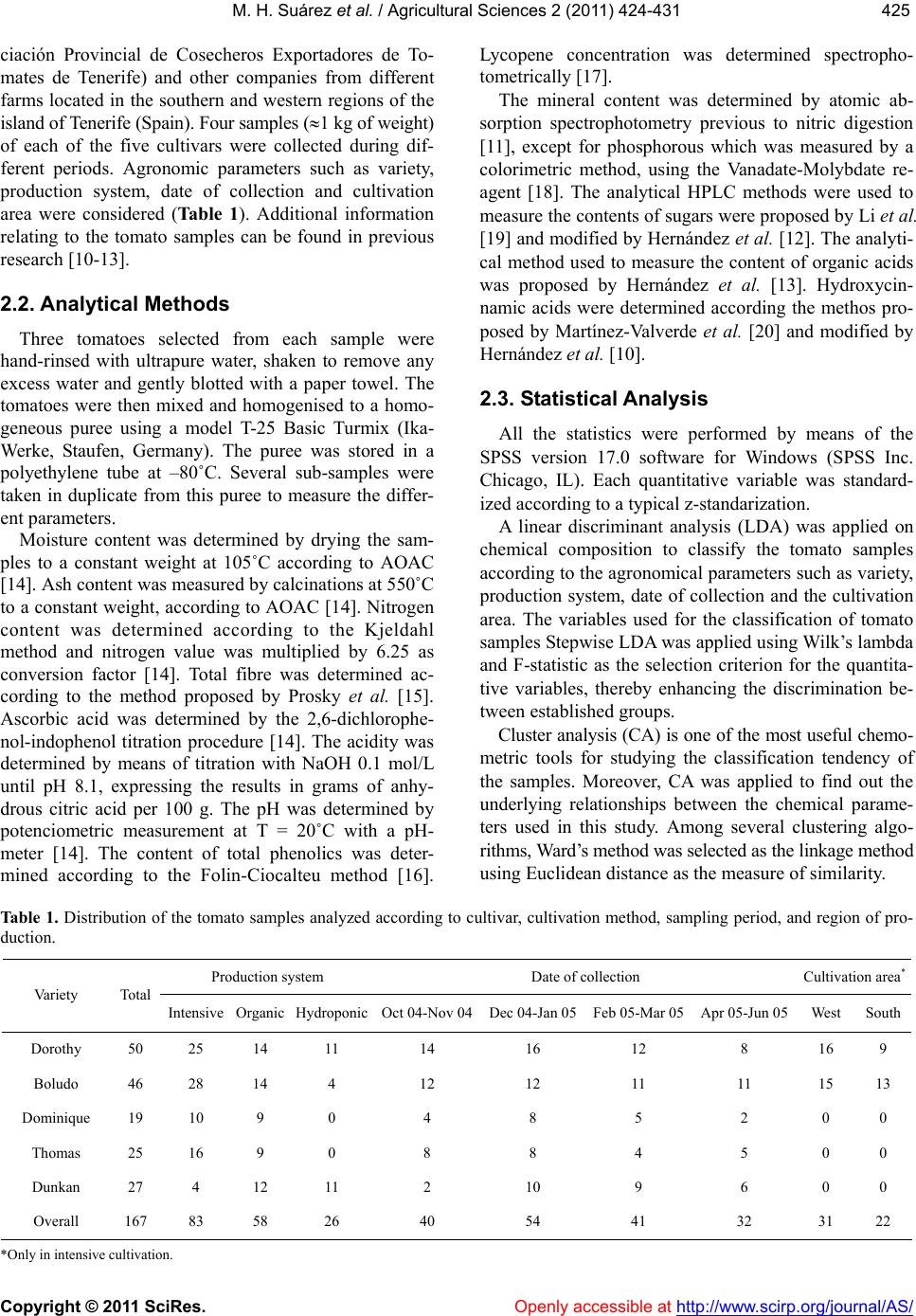

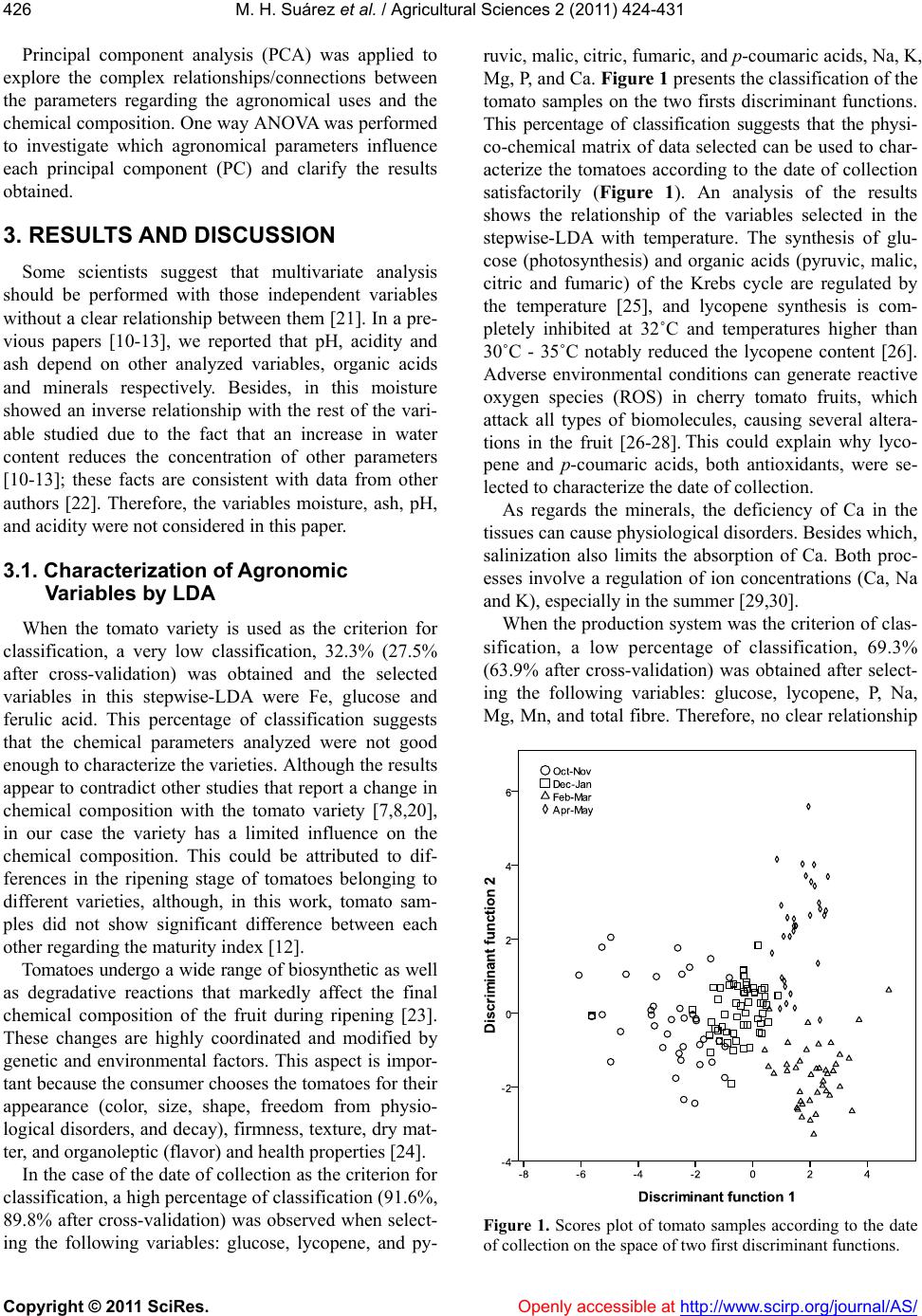

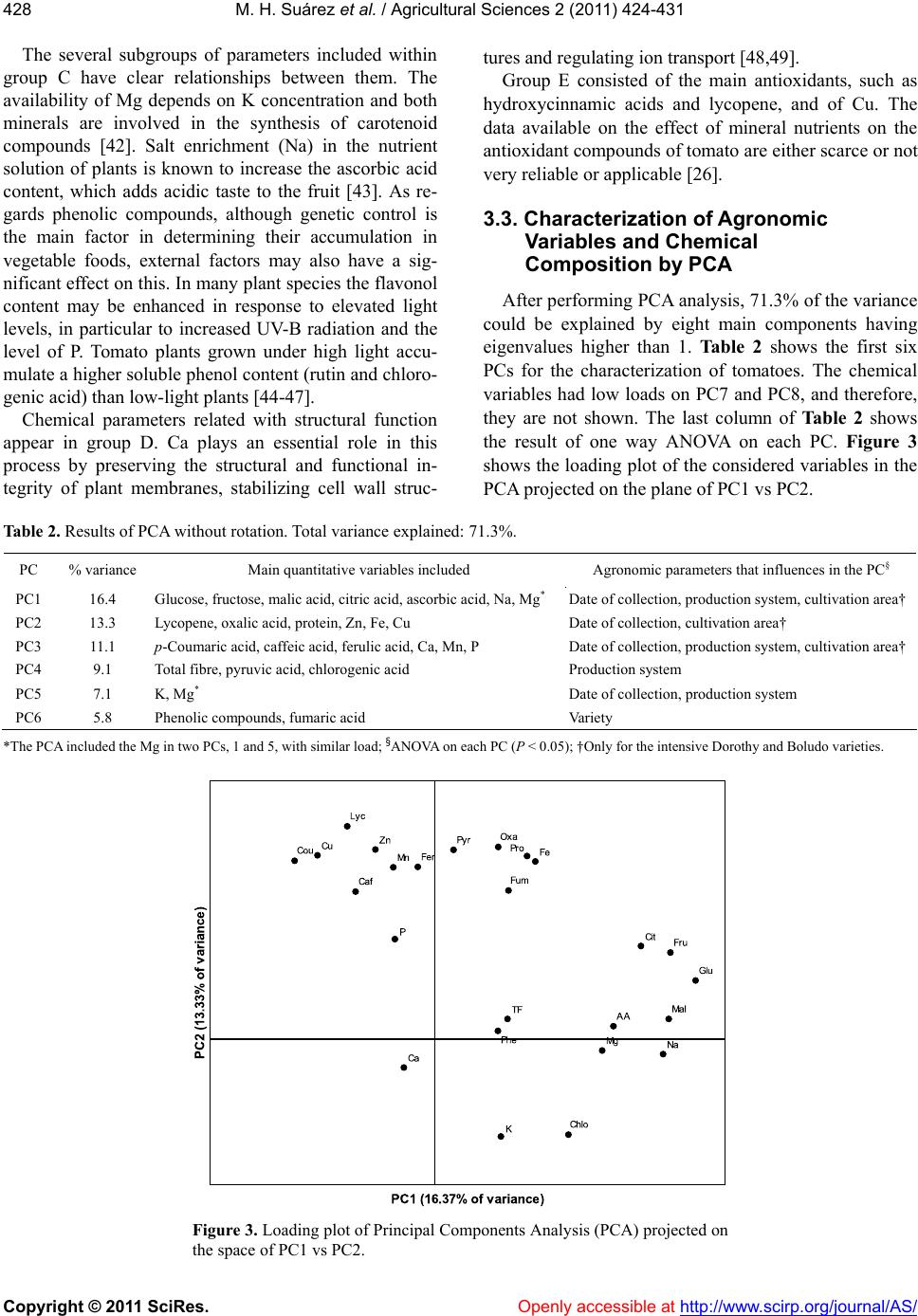

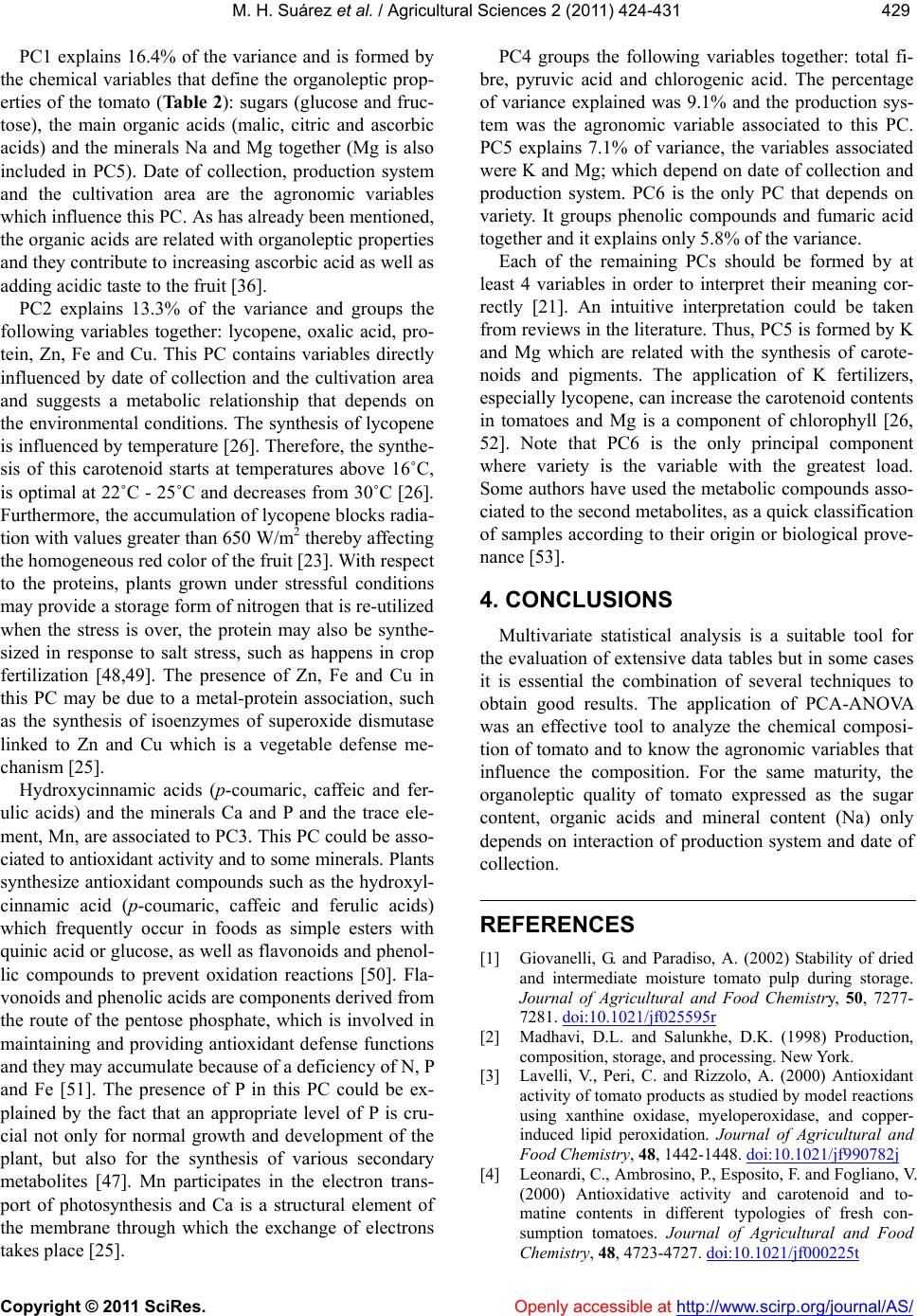

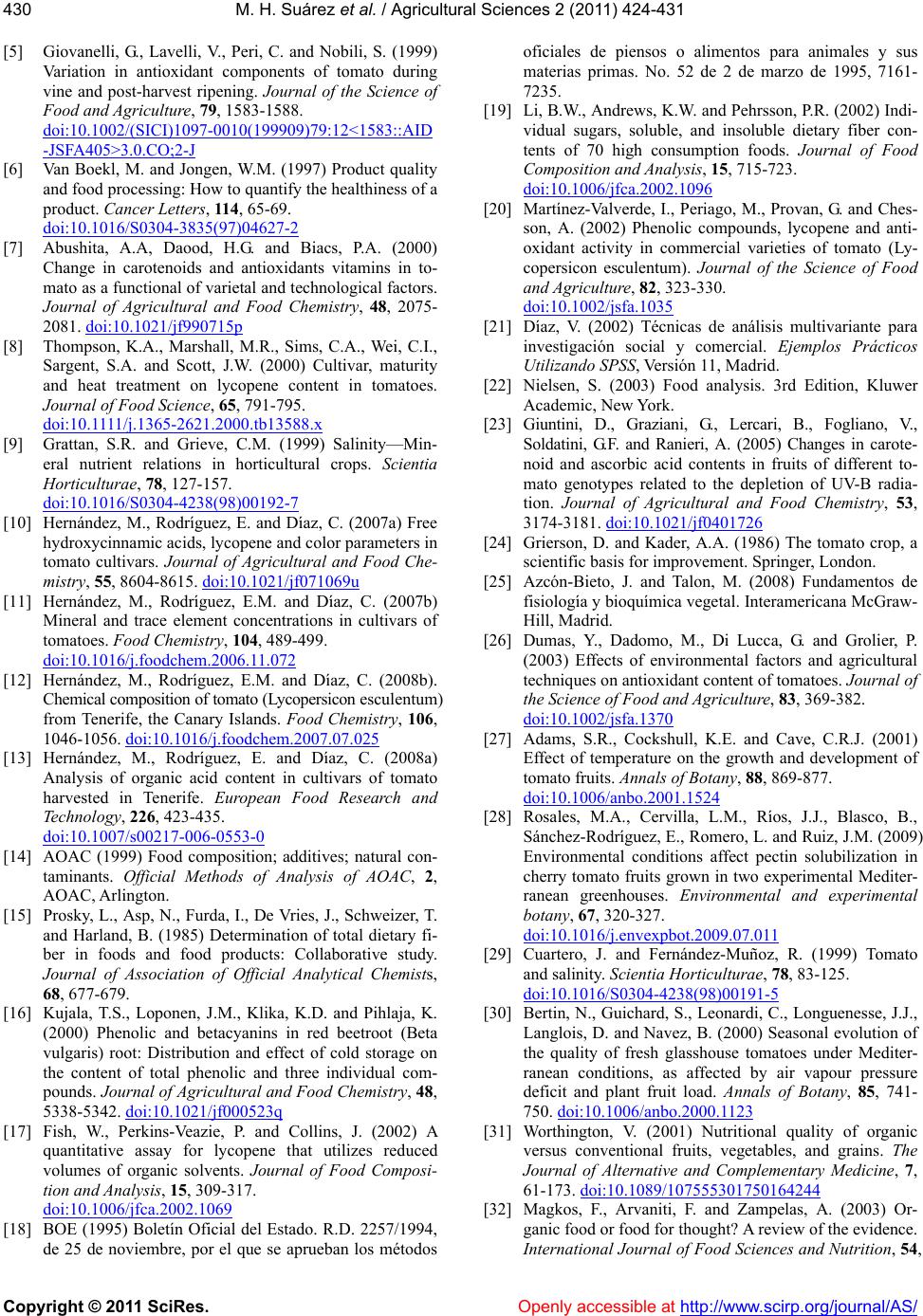

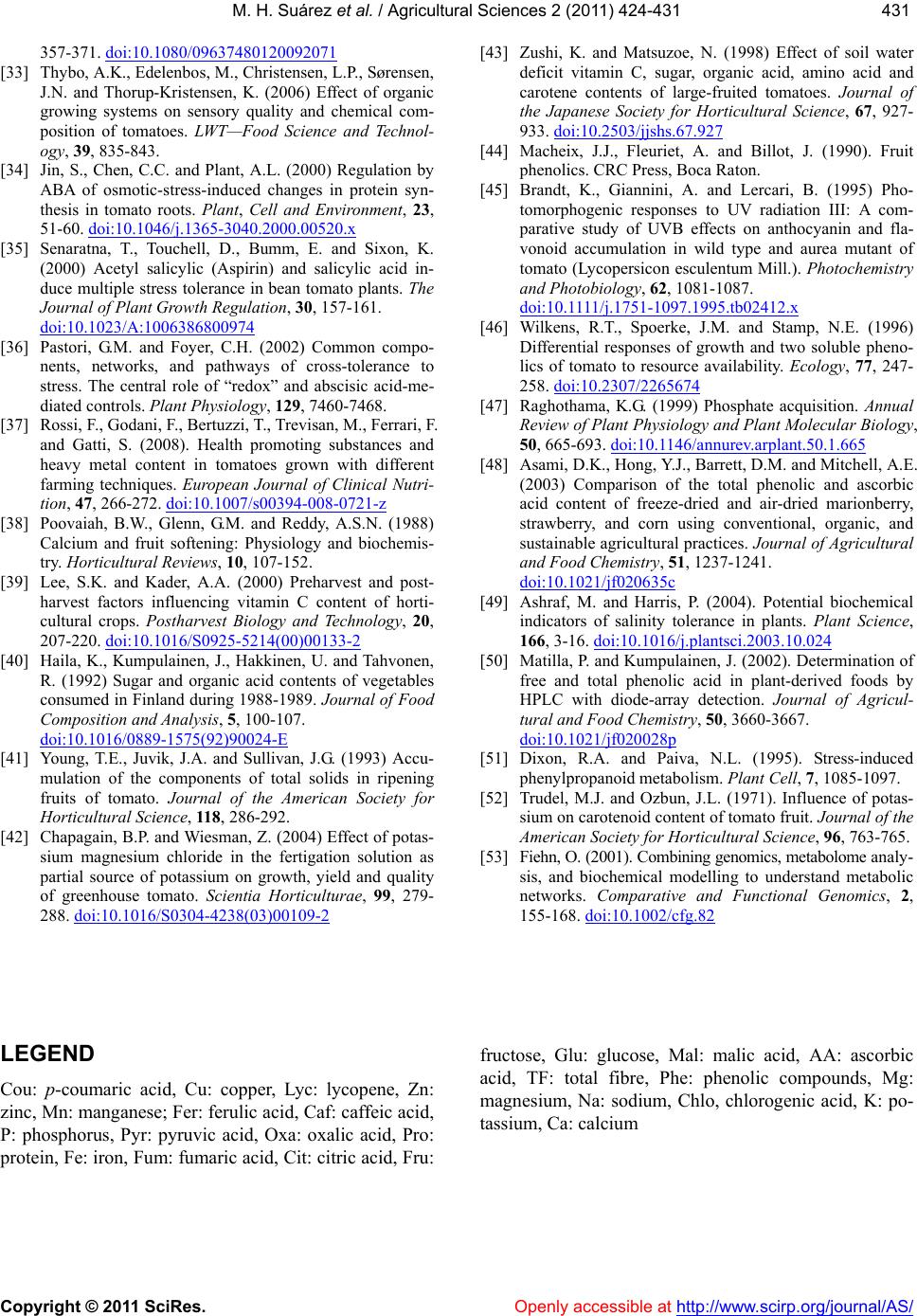

|