Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

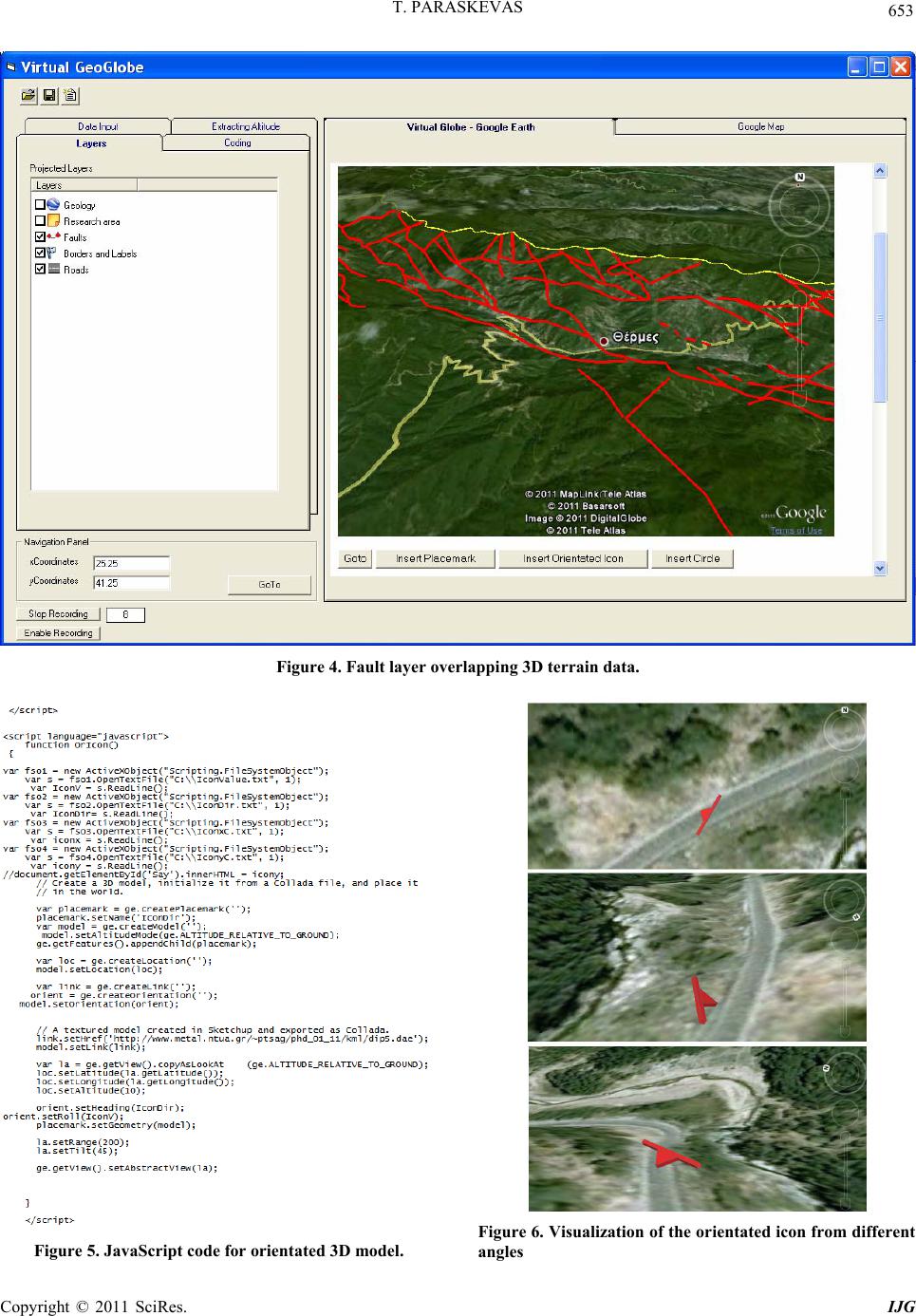

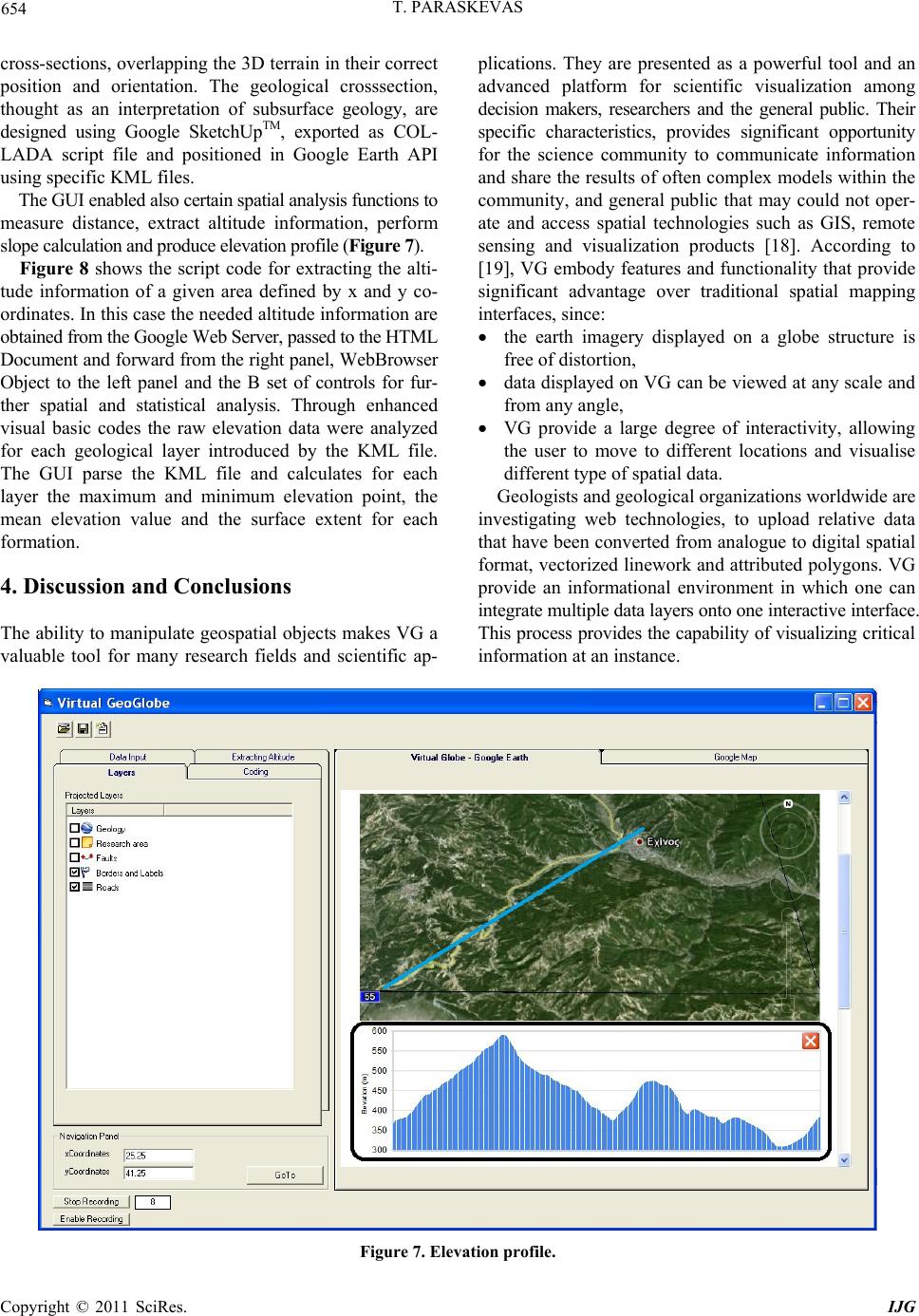

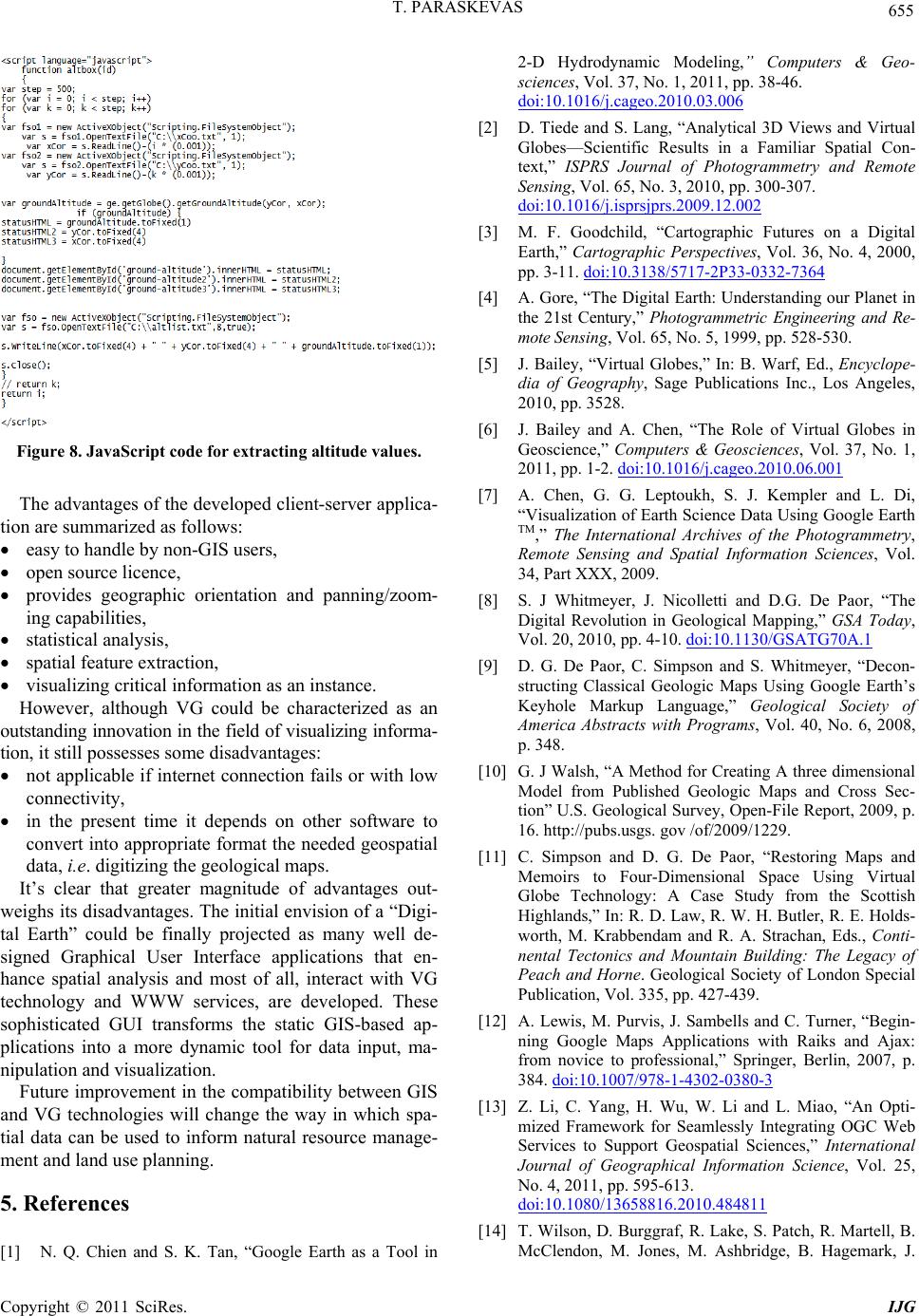

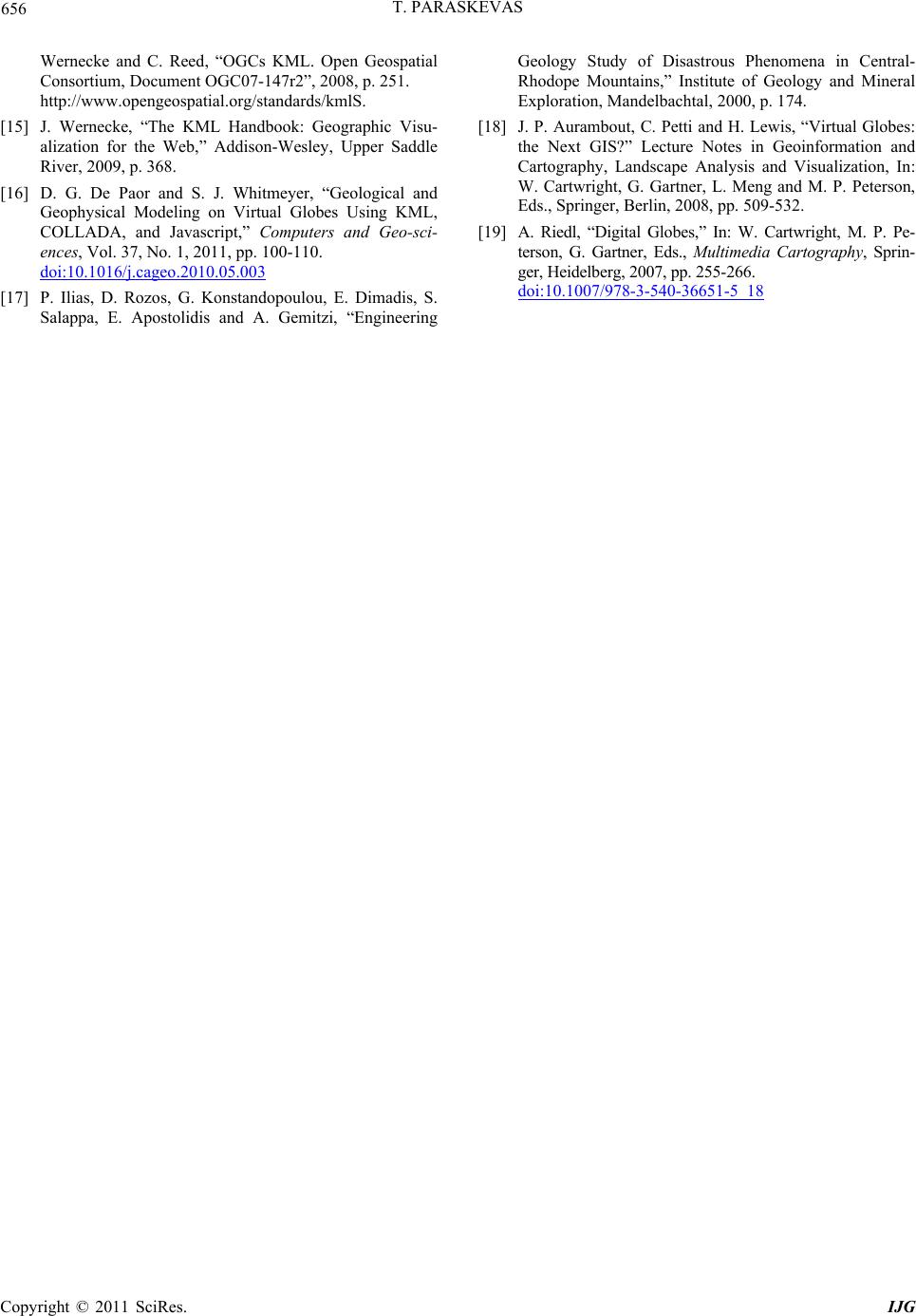

International Journal of Geosciences, 2011, 2, 648-656 doi:10.4236/ijg.2011.24066 Published Online November 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ijg) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG Virtual Globes and Geological Modeling Tsangaratos Paraskevas Laboratory of En gi neeri n g G e ol o gy—Hydrogeol ogy, Sectio n of Geosci ences, Scho ol of Mining and Metallurgical Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece E-mail: ptsag@metal.ntua.gr Received May 27, 2011; July 9, 2011; accepted Septe mber 14, 2011 Abstract Virtual Globes such as Google Earth TM, revolutionize the way scientists conduct their research and the way the general public use geospatial-related data and information. Improvement in the processing power and storage capacities of computers, along with the increased Internet accessibility and connectivity, has sup- ported the usage of Virtual Globes technologies. Even more, software releases of freely downloadable Vir- tual Globes, such as Google Earth and NASA World Wind, has sparked an enormous public interest and in- creased people’s awareness of spatial sciences. In this study, the Virtual Globes (VG) revolution is discussed and a client-server Graphical User Interface (GUI) application is presented. The developed application en- ables Google Earth TM Application Program Interface and activates spatial analysis, through enhanced JavaScripts and Visual Basic script codes. The main scope was to present the methodology followed during geological modeling along with the application capabilities when handling with data derived from digitized geological maps and field measurements. Keywords: Virtual Globe, Geological Modeling, Graphical User Interface, Spatial Analysis 1. Introduction In every geosciences model that simulates a natural sys- tem, interactive data manipulation and visualization, are the most essential tools [1]. The projection of these pro- cedures and their analytical results, are usually presented by the form of digital or analogous thematic maps [2]. Digital or analogous, maps actually help users to under- stand the spatial context of things, concepts, conditions, process or events, simulating parts of the environment and every day life. However, due to limitations of the procedure following the construction of analogous maps and in some extent 2D digital maps, this form of com- munication among scientists and the general public is not fully appreciated. Maps are flat, providing only a single level of detail, they are static and the constructio n is usu- ally slow [3]. Al Gore, former vise president of USA, envisioned a “Digital Earth”, a multi-resolution, 3D rep- resentation of the planet, into which we could embed vast quantities of geo-referenced d ata [4]. Displaying the real-world, either as a “mirror” of what we see, or as spe- cialized display of social, economic, infrastructure or environmental data. This form of representation over- comes the limitations that an alogo us and 2D digital maps own. By the end of the millennium, it was well estab- lished the idea of a computer application, allowing users to browser and search geographically indexed informa- tion, projected on a cartographic representation of the Earth in various scales and projections [5]. The materi- alization of this idea was based on technological advan- tages, such as orbiting satellites with spatial resolution of a few meters, improvements in hardware and software and the growth of broadband internet, where users have World Wide Web (WWW) access without slow speed and telephone line disruption [6]. Modeling a Virtual Earth or a Virtual Globe (VG), for effective communica- tion, enhancing science, distributing knowledge, under- stand and insight phenomena and natural process, that was the idea. The advantages of implying such an idea are fully un- derstood when trying to visualize geoscientific data. The impact that those images have on viewers, are certainly more direct and more powerful than those produced by analogous and 2D static digital maps. Geology and ge- ology-based scien ce are not an exceptio n. The geological surface extent and lithological structure, the spatial dis- tribution of faults and zones of discontinuities, the hy- drographical network and other points of interest, are basic knowledge, necessary for understanding and inter- preting the geological model that represents the studied  T. PARASKEVAS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG 649 area. The better they are visualized, the better they are understood. However, the over mentioned processes of- ten requires a working knowledge of image processing and 3D modeling software and the ability to write script codes from the side of the end-user. The main scope of this study was to provide a meth- odology through a well designed Graphical User Inter- face application that enables the Virtual Globe technol- ogy providing a helpful tool for handling geological data in a more sophisticated manner. 2. VG Technology and Geological Data VG are presented as 3D software models, which are ca- pable of modelling the Earth or other environments of the universe, like Moon, Venus and Jupiter. They pro- vide the user with the ability to freely move around by changing the viewing angle and position. Compared to a convention al globe, VG have the add itional capability of representing many different layers of information on the surface of the Earth. These information layers concern spatial and non-spatial attributes. Specifically, VG can display, man-made features such as infrastructure net- works and buildings, elevation data or representations of demographic quantities such as population or outcrop production. They pro vide the ability to browse maps and geospatial data on the internet using the relative servers. They can handle data such as geodatabases, shapefiles, KML/KMZ, GPX and raster formats (JPEG, GeoTIFF, MrSID) and integrate a wide variety of context like pho- tos, videos, documents, 3D models and place them in a geographic content. Recen t applications of 3D modelling software, such as Google SketchUpTM have led to the development of 3D earth science models that can be di- rectly incorporated into VG scenes. However, unlike GIS maps, VG display this information in photorealistic, life - like three dimensions. Few of them can perform spatial functions, e.g. visib ility, modelling , and prox imity search, ArcGIS Explorer. Finally, add-ons and small extensions, written in C#, VB or J# scripts can be loaded and com- piled, adding new functionality to the programs. One of the fields, in which VG technology have dy- namically entered, is in the geoscientific domain. A gr eat number of VG applications have been used in research fields such as, global climate change, weather forecasting, natural disasters (e.g. tsunamis, hurricanes), environment conservation, travel, nature, people and culture, history illustration, avian flu, online gaming, etc. [7]. As it can be ascertained, map compilation and visualization of geological related data, are undergoing a revolution in the way they are performed. Assisted by Global Posi- tioning System (GPS), Geographic Information System (GIS), Web Map Services (WMS) and Virtual Globe (VG) technology, the process and methods of geological modelling have marked a major advance [8]. Consider- ing the performance of various procedures that are im- plemented for geological modeling through the use of VG technology, [9] demonstrated a map deconstruction process, named “GIS-ification”. During the process, the analogue geological maps are transformed into interact- tive maps and are introduced in Google Earth TM. Each lithological unit of the map is scanned and introduced as a separate layer having transparent mask. A similar step by step process is described by [10], who presented a relatively inexpensive and rapid method for creating a 3D model of geology from published quadrangle scale maps and cross-sections, using Google Earth TM and Google SketchUpTM software. Analogous procedure was presented by [11]. Another method for coupling VG with geophysical hydrodynamic models was presented by [1]. Firstly, users draw p olygons on the Goog le Earth screen. These features are then saved in a KML file which is read using a script file written in Lua programming lan- guage. After the hydrodynamic simulation is being per- formed, another script file is used to convert the resulting output text file int o a KML file for visualization, where t he depths of inundation are represented by the colour of dis- crete point icons. The visualization of a wind speed vector field was also included as a supplementary example. All of those procedures share the same characteristic. They are developed by Earth scientists in order to effect- tively distribute their research outcomes to both, other scientists and the general public. However, at the present time, the available software has limitations when it comes to mapping and modeling features such as geo- logical orientation data, dip and dip directions values for faults, and geological structure features. In ad dition, they do not perform spatial nor sta tistical functions over areas of interest, limiting the usage of the VG, to be a tool for data input and visuali zat i on. The main scope of this study is to develop a form of client-server GUI application, transforming the static GIS-based applications into a more dynamic tool for data input, manipulation and visualization. A GUI that pro- vides the end user, with spatial analysis functions, having also the ability of presenting data in a familiar spatial context, easily to be found online and accessed any time and in any place, though VG technology. 3. Methods and Material It is well known that there has been an increasing num- ber of amazing technologies that can boost our software application to a higher level of power and usability. Ajax (Asynchronous JavaScript +XML) model is one of them [12,13]. It seems that these technologies have renewed  T. PARASKEVAS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG 650 the main objective of the Web development community which is to create applications that are powerful and re- sponsive, like any desktop based application, having though the advantage of accessibility via the WWW. With Ajax, web applications can retrieve data from the server asynchronously in the background without inter- fering with the display and behaviour of the existing page. The use of Ajax techniques has led to an increase in interactive and dynamic interfaces on web pages. Google Earth API, Google Maps and its Java Script API, are free services, allowing anyone to build sophisticated 3D map applications that embraces the Ajax model. The Google Earth API can display placemarks, lines, poly- gons, overlays and 3D models, on the imagery just as the standalone version of Google Earth can. The plug-in supports several of the Google Earth layers of informa- tion, including terrain data, infrastructure network, bor- ders and buildings. The Google Earth API can be used to develop dy- namic Client Server and Web based applications. In this study, a Client-Server Application (CSA) was devel- oped. A typical CSA describes an application architect- ture in which the client requests an action or service from the provider of service, the server. Considering a Web browser and a Web server, when we address a URL in the browser window, it requests a page from a Web server. The server returns an HMTL page to the client, which parses the page (data) and displays it on the computer. In this study, the role of the client is played by the devel- oped GUI, while the Google Web Server acts as the re- quired Web server that returns to the client requested data. The developed GUI is a CSA for displaying very large, global scale, terrain models. The terrain database is stored on a Google Web Server and the client program fetches the data required for generating an image on our screen with the wanted resolution. As moving around, the program loads and displays data as needed. 3.1. Data Format The process of data input using Google Earth, adopts Keyhole Markup Language (KML) as many of the avail- able VG do. KML is used as the format for describing, organizing and visualizing geographical objects [14]. It represents a hierarchical data system where the geo- graphical objects can be populated in a n ested tree struc- ture [15]. There are mainly three types of methods that can be used to handle geospatial data with the use of KML format [7]: using binary values, that can be stored and organized as KML elements namely: points, linestring, linear- ring, polugon, multigeometry, using image in the format of png, jpeg, gif, that can be introduced as KML elements namely: photoOver- lay, screenOverlay and groundOverlay, using 3D models, which can be modeled base on bi- nary values, images, Sketchup models, etc. The description for every object is provided by fol- lowing a certain structure, using pairs of KML tags, in which, information about the number of objects, their coordinates and style, is presented. For displaying a point, the KML file takes the following form: <Point>, opening tag of Object <name> TestPoint_A </name>, naming the point <coordinates> 24.015, 38.174 </coordinates>, speci- fying the coordinates of the object </Point>, closing tag of Object KML’s full abilities are presented when using 3D mod- els, combined with COLLADA (COLLAborative Design Activity) model. COLLADA is defined as an open stan- dard XML schema for exchanging digital assets among various graphics software applications, usually id entified with a “.dae” (digital asset exchange) filename extension. Models are constructed and defined independently of the Google Earth application, having their own coordinate space and using applications such as SketchUpTM, 3D Studio Max, Softimage XSI or Maya. However, when a 3D model is imported into Google Earth, it is translated, rotated and scaled to fit in to the Google Earth coordinate system. As already mentioned, many software that enables VG technology, have the ability to handle ESRI shapefiles and import simple text files which refer to geospatial data. To upload a point ESRI file, the first action is to transform the file into a plain text format. The next thing is to parse the needed information, by applying a simple rule searching script and retrieve the corresponding value, which has to do with coordinates, altitude and name or ID of the observation point. Finally, the text’s structure is reformed and saved in a KML format. 3.2. System Architecture and Main Characteristics The developed CSA was designed and compiled using Visual Basic programming language, enabling the Google Earth Application Program Interface. It consists of a sin- gle form that contains all the specific scripts and codes that are capable of performing spatial and statistical analy- si s functions . The form contains a split panel control oriented verti- cally. The left part contains the controls that are used to add and manipulate the available data. There are two sets of controls in this panel. The first set contains all the necessary controls for the data input and the data trans- formation procedures. The second set of controls is de-  T. PARASKEVAS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG 651 signed to perform spatial and statistical analysis, from the available or the requ ested data. The right panel of the control contains a WebBrowser Object, docked into it. This control contains objects such as HTML Document or others. In the case presented, the HTML Document was the Google Earth API. Events that occur in the Google Earth API which is contained in the WebBrowser Object are captured and forward to a procedure in the left panel of the Form. A Visual Basic script which is embodied in the form’s source code, executes specific functions in response to the forwarded Events. The same procedure is executed with Events and Scripts performed in the Form and forwarded to Google Earth HTML Object (Figure 1). Google Earth API does not include the option of up- loading a KML file from the local disk of a user, mainly for security reasons set by the Internet Explorer protocol. There are few ways to bypass this obstacle, the latest of which is adopted by the developed GUI: Writing a proxy that uses an HTML Form to upload the file to a server and then make it available on the local machine. Changing the security settings of the HTML object by adding it to the “trusted sites” and changing it from “disab le” to “prompt”, th e “initialize and script Ac tiveX controls not marked safe for scripting” checkbox. This option uses the ActiveXObject (“Scripting. FileSyste- mObject”). Getting a string of the local KML file and pass this string to the parse KML method of the API. One of the main features of the developed VG is its ability to handle orientated geological data and present them in a way they don’t loose their spatial characteris- tics. The KML file that references the COLLADA file contains a Lat-Long insertion point and information con- cerning orientation, and scale information. The KML file also contained information about the lithological unit in which each observation was placed. With the use of a few script lines introduced in the source code of the GUI, the dip/dip direction icon was dynamically orientated relative to the geographic north, so that when the view orientation was changed, the dip/dip direction icon ro- tates, so as to maintain a constant azimuth. A similar code can be found in the paper presented by [16], how- ever in the developed GUI, the user is able to introduce an orientated icon without producing any programming code. The user simply imports the icon referring to the field measurements that are introduced into the form of the GUI. The developed VG embodies additional functions and spatial analysis tools, such as 3D distance measurement, slope calculation, terr ain section an alysis, know ledg e and information that help the users understand the actual geo- graphical and geological environment. Specifically, the user has the ability to profile the surface and export screen- shots, as an image file but also to export the elevation data into a text format file, for further spatial calcula- tions. 3.3. Research Area The study area concerns the wider area of the Perfection of Xanthi, ap proximately 800 Km2, bounded to the north by the Greek-Bulgarian borders and extended to the south up to the Neogene Thrace basin (Figure 2). The geological structure consisted of a marble unit (marbles and schists), a gneissic unit (magmatites, gneisses, am- phibolites and ultra maf ic ro c ks) o f Palaeo zoic ag e an d th e Tertiary mollasic and igneous rocks. The elevation values of the area, varied between 30 to 1800 m approximately. However, from a morphological point of view, the area is characterized as mountainous. The available data came by digitizing the prev ious conducted geo logical map [17], at 1:50,000 scale as well as by field observations that represent the geological structure. Figure 1. The general schema design. Figure 2. Research area.  T. PARASKEVAS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG 652 Each GIS geological map is represented by a number of ESRI shapefiles (Figures 3 and 4). Specifically, the files contain: geological arcs and polygons shape files (.SHP), geological symbols shape files (.SHP), base map image file (.tif, .jpeg, .bmp). Each of the projected layers was converted from EGSA’87, Greek Geodetic Reference System (1987), to WGS84 Geographic Coordinate Sys- tem. During the implementation, named and scaled place- mark icons were placed in order and exported as KML files. 3.4. Evaluating the Developed Application In order to test the efficiency of the developed GUI, the case of visualizing the field observations was investi- gated (dip and dip direction) while evaluating the pro- duced images and projections for the tectonic feature that was plotted. Dip and dip direction, refer to the orientation of a geo- logical observation point. The dip direction of a fault, or a joint, is projected as a line, representin g the intersec tion o f the observation point with a horizontal plane and it is characterized by a positive angle between 0˚ - 360˚. On a static 2D geological map, this is represented by a short straight line segment oriented, parallel to the dip direc- tion line. The baseline orientation is north but this could be true north, grid north or magnetic north. A dip value is actually the steepest angle of descent of a titled observation point relative to a horizontal plane and is characterized by a positive angle between 0˚ - 90˚. The symbol used in a static 2D map, is a short line at- tached to the symbol of the dip direction, pointing in the direction which the planar surface is dipping down. As mentioned by De Paor et al. 2010, Google Earth by de- fault handles placemark icons, as dip and dip direction are, dynamically orientated relative to the viewer, creat- ing though a false visualization of the observation point when the user choose to change the view angle. In the developed GUI, the dip and dip direction values are imported through the left panel while after been transformed into KML file they are forward to the right panel, the WebBrowser Object. The HTML Document which contains the Google Earth API, also includes action buttons that, when clicked, perform certain functions. In the case of placing the oriented placemark icons the function is written using Javascript code as the one pre- sented in Figure 5. The outcome of this procedure is the projection of the oriented observatio n poin ts in su ch a manner that it cou ld produce a true visualization of the observation point, even when the user changes the view angle (Figure 6). A similar procedure was adopted for placing geological Figure 3. Geological layer overlapping 3D terrain data.  T. PARASKEVAS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG 653 Figure 4. Fault layer overlapping 3D terrain data. Figure 5. JavaScript code for orientated 3D model. Figure 6. Visualization of the orientated icon from different angles  T. PARASKEVAS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG 654 cross-sections, overlapping the 3D terrain in their correct position and orientation. The geological crosssection, thought as an interpretation of subsurface geology, are designed using Google SketchUpTM, exported as COL- LADA script file and positioned in Google Earth API using specific KML files. The GUI enabled also certain spatial analysis functions to measure distance, extract altitude information, perform slope calculation and produce elevation profile (Fi gure 7). Figure 8 shows the script code for extracting the alti- tude information of a given area defined by x and y co- ordinates. In this case the needed altitu de information are obtained from the Google Web Server, passed to the HTML Document and forward from the right panel, WebBrowser Object to the left panel and the B set of controls for fur- ther spatial and statistical analysis. Through enhanced visual basic codes the raw elevation data were analyzed for each geological layer introduced by the KML file. The GUI parse the KML file and calculates for each layer the maximum and minimum elevation point, the mean elevation value and the surface extent for each formation. 4. Discussion and Conclusions The ability to manipulate geospatial o bjects makes VG a valuable tool for many research fields and scientific ap- plications. They are presented as a powerful tool and an advanced platform for scientific visualization among decision makers, researchers and the general public. Their specific characteristics, provides significant opportunity for the science community to communicate information and share the results o f often complex models within the community, and general public that may could not oper- ate and access spatial technologies such as GIS, remote sensing and visualization products [18]. According to [19], VG embody features and functionality that provide significant advantage over traditional spatial mapping interfaces, since: the earth imagery displayed on a globe structure is free of distortion, data displayed on VG can be viewed at any scale and from any angle, VG provide a large degree of interactivity, allowing the user to move to different locations and visualise different type of spatial data. Geologists and geological organizations worldwide are investigating web technologies, to upload relative data that have been converted from analogue to digital spatial format, vectorized linework and attributed polygons. VG provide an informational environment in which one can integrate multiple data layers onto one interactive interface. This process provides the capability of visualizing critical information at an instance. Figure 7. Elevation profile.  T. PARASKEVAS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG 655 Figure 8. JavaScript code for extracting altitude values. The advantages of the developed client-server applica- tion are summarized as follows: easy to handle by non-GIS users, open source licence, provides geographic orientation and panning/zoom- ing capabilities , statistical analysis, spatial feature extraction, visualizing critical information as an instance. However, although VG could be characterized as an outstanding innovation in the field of visualizing informa- tion, it still possesses some disadvantages: not applicable if intern et connection fails or with low connectivity, in the present time it depends on other software to convert into app ropriate format the needed geospatial data, i.e. digitizing the geological maps. It’s clear that greater magnitude of advantages out- weighs its disadvantages. Th e initial envision of a “Digi- tal Earth” could be finally projected as many well de- signed Graphical User Interface applications that en- hance spatial analysis and most of all, interact with VG technology and WWW services, are developed. These sophisticated GUI transforms the static GIS-based ap- plications into a more dynamic tool for data input, ma- nipulation an d vi sual i zat i on. Future improvement in the compatibility between GIS and VG technologies will change the way in which spa- tial data can be used to inform natural resource manage- ment and land use planning. 5. References [1] N. Q. Chien and S. K. Tan, “Google Earth as a Tool in 2-D Hydrodynamic Modeling,” Computers & Geo- sciences, Vol. 37, No. 1, 2011, pp. 38-46. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2010.03.006 [2] D. Tiede and S. Lang, “Analytical 3D Views and Virtual Globes—Scientific Results in a Familiar Spatial Con- text,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Vol. 65, No. 3, 2010, pp. 300-307. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2009.12.002 [3] M. F. Goodchild, “Cartographic Futures on a Digital Earth,” Cartographic Perspectives, Vol. 36, No. 4, 2000, pp. 3-11. doi:10.3138/5717-2P33-0332-7364 [4] A. Gore, “The Digital Earth: Understanding our Planet in the 21st Century,” Photogrammetric Engineering and Re- mo t e S ensing, Vol. 65, No. 5, 1999, pp. 528-530. [5] J. Bailey, “Virtual Globes,” In: B. Warf, Ed., Encyclope- dia of Geography, Sage Publications Inc., Los Angeles, 2010, pp. 3528. [6] J. Bailey and A. Chen, “The Role of Virtual Globes in Geoscience,” Computers & Geosciences, Vol. 37, No. 1, 2011, pp. 1-2. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2010.06.001 [7] A. Chen, G. G. Leptoukh, S. J. Kempler and L. Di, “Visualization of Earth Science Data Using Google Earth TM,” The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Vol. 34, Part XXX, 2009. [8] S. J Whitmeyer, J. Nicolletti and D.G. De Paor, “The Digital Revolution in Geological Mapping,” GSA Today, Vol. 20, 2010, pp. 4-10. doi:10.1130/GSATG70A.1 [9] D. G. De Paor, C. Simpson and S. Whitmeyer, “Decon- structing Classical Geologic Maps Using Google Earth’s Keyhole Markup Language,” Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, Vol. 40, No. 6, 2008, p. 348. [10] G. J Walsh, “A Method for Creating A three dimensional Model from Published Geologic Maps and Cross Sec- tion” U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report, 2009, p. 16. http://pubs.usgs. gov /of/2009/1229. [11] C. Simpson and D. G. De Paor, “Restoring Maps and Memoirs to Four-Dimensional Space Using Virtual Globe Technology: A Case Study from the Scottish Highlands,” In: R. D. Law, R. W. H. Butler, R. E. Holds- worth, M. Krabbendam and R. A. Strachan, Eds., Conti- nental Tectonics and Mountain Building: The Legacy of Peach and Horne. Geological Society of London Special Publication, Vol. 335, pp. 427-439. [12] A. Lewis, M. Purvis, J. Sambells and C. Turner, “Begin- ning Google Maps Applications with Raiks and Ajax: from novice to professional,” Springer, Berlin, 2007, p. 384. doi:10.1007/978-1-4302-0380-3 [13] Z. Li, C. Yang, H. Wu, W. Li and L. Miao, “An Opti- mized Framework for Seamlessly Integrating OGC Web Services to Support Geospatial Sciences,” International Journal of Geographical Information Science, Vol. 25, No. 4, 2011, pp. 595-613. doi:10.1080/13658816.2010.484811 [14] T. Wilson, D. Burggraf, R. Lake, S. Patch, R. Martell, B. McClendon, M. Jones, M. Ashbridge, B. Hagemark, J.  T. PARASKEVAS Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJG 656 Wernecke and C. Reed, “OGCs KML. Open Geospatial Consortium, Document OGC07-147r2”, 2008, p. 251. http://www.opengeospatial.org/standards/kmlS. [15] J. Wernecke, “The KML Handbook: Geographic Visu- alization for the Web,” Addison-Wesley, Upper Saddle River, 2009, p. 368. [16] D. G. De Paor and S. J. Whitmeyer, “Geological and Geophysical Modeling on Virtual Globes Using KML, COLLADA, and Javascript,” Computers and Geo-sci- ences, Vol. 37, No. 1, 2011, pp. 100-110. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2010.05.003 [17] P. Ilias, D. Rozos, G. Konstandopoulou, E. Dimadis, S. Salappa, E. Apostolidis and A. Gemitzi, “Engineering Geology Study of Disastrous Phenomena in Central- Rhodope Mountains,” Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration, Mandelbachtal, 2000, p. 174. [18] J. P. Aurambout, C. Petti and H. Lewis, “Virtual Globes: the Next GIS?” Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography, Landscape Analysis and Visualization, In: W. Cartwright, G. Gartner, L. Meng and M. P. Peterson, Eds., Springer, Berlin, 2008, pp. 509-532. [19] A. Riedl, “Digital Globes,” In: W. Cartwright, M. P. Pe- terson, G. Gartner, Eds., Multimedia Cartography, Sprin- ger, Heidelberg, 2007, pp. 255-266. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-36651-5_18 |