Vol.3, No.11, 677-683 (2011) doi:10.4236/health.2011.311114 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Quit smoking improves gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and quality of life Kou Nakajima1, Akihito Nagahara1*, Akihiko Kurosawa1, Kuniaki Seyama2, Daisuke Asaoka1, Taro Osada1, Mariko Hojo1, Sumio Watanabe1 1Department of Gast r o e n t e r ology, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; *Corresponding Aut hor: nagahara@juntendo.ac.jp 2Department of Res p i r a tory Medicine, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan. Received 11 September 2011; revised 6 October 2011; accepted 21 October 2011. ABSTRACT Background: Smoking is considered to be risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The present study aimed to reveal whether quit smoking improves GERD symp- toms and QOL of patients. Methods: In this pro- spective study, 33 patients who participated in a 12-week quit smoking program filled out the Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of GERD (FSSG) questionnaire, and SF8 QOL question- naire. Patients filled out the questionnaires at baseline and during the program at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 8 weeks and 12 weeks. In the FSSG, the responses were scored and the reflux score (RS), dysmotility score (DS) and total score (TS) were calculated. Results: There were 22 males and 11 females. Their mean age was 54.8 ± 13.0 (mean ± SD) yr, BMI was 22.9 ± 4.0, and duration of smoking was 33.5 ± 12.5 years. Ten patients belonged to GERD subgroup (baselineFSSGscore ≥ 8). All patients were successful at quit smok- ing. Scores of TS/RS/DS are 8.6 ± 1.8 (mean ± SE)/4.2 ± 0.9/4.5 ± 0.9 at baseline, 4.7 ± 1.6**/2.5 ± 0.9**/2.3 ± 0.7** at 2 w, 5.7 ± 1.3**/2.6 ± 0.6*/3.0 ± 0.7* at 4 w, 4.5 ± 1.4*/2.2 ± 0.8*/2.3 ± 0.8* at 8 w and 3.7 ± 1.2**/1.7 ± 0.6**/2.0 ± 0.7** at 12 w, re- spectively (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs. baseline). Among GERD subgroup, Scores of TS/RS/DS are 18.0 ± 2.9/8.9 ± 1.6/9.1 ± 1.5 at baseline, 8.8 ± 3.0/5.1 ± 1.7/3.7 ± 1.6 at 2 w, 10.8 ± 2.9/5.4 ± 1.6/5.4 ± 1.5 at 4 w, 7.6 ± 2.9*/4.1 ± 1.6/3.5 ± 1.5* at 8 w and 7.1 ± 2.9*/3.2 ± 1.6*/3.9 ± 1.5* at 12w, respectively. Regarding QOL, physical compo- nent score has significantly improved at 2, 4, 8 and 12 w and mental component score at 4w, respectively. Conclusions: Quit smoking sig- nificantly improved not only GERD symptoms but also QOL, indicating that quit smoking might be an option in the treatment strategy of GERD symptoms. Keywords: Quit Smoking; FSSG; GERD; SF8 1. INTRODUCTION Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are known to be re- lated to the habit of smoking, which is reportedly an aggravating factor of especially GERD symptoms in- cluding heartburn [1-3]. Quit smoking is well known to have positive effect on personal health, on the contrary, some reports described that quit smoking brought about insomnia, obesity, restlessness, stress, or psychological instability [4] and was followed by constipation [5]. However, there has been no report describing the rela- tionship between quit smoking and GERD symptoms. To reveal whether quit smoking could improve GERD symptoms and QOL, patients who participated in the quit smoking program at the outpatient clinic of the De- partment of Respiratory Medicine in Juntendo Univer- sity Hospital were asked to fill out the Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of GERD (FSSG) questionnaire and SF8 QOL questionnaire. 2. METHODS In this prospective study, patients who joined a 12- week quit smoking program at the outpatient clinic of the Department of Respiratory Medicine in Juntendo University Hospital between June 2008 and April 2009, were asked to fill out the FSSG questionnaire as well as the SF8 QOL questionnaire. All patients were not ad- ministered proton pump inhibitors. The FSSG was designed to evalu ate GERD symptoms in the Japanese population. The FSSG consists of 12 items; 7 items concern gastric acid reflux and 5 items  K. Nakajima et al. / Health 3 (2011) 677-6 83 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 678 concern dysmotility sy mptoms (Figure 1). Patients were asked to rate each item on a scale of 0 to 4. Comparisons of the scores were made for each item between before and after starting (at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks) the quit smoking program. The RS was calculated as the sum of the scores of the 7 items concerning gastric acid reflux, and DS was calculated as the sum of the scores of the 5 items concerning dysmotility symptoms. TS was calcu- lated as the sum of the scores of all 12 items. The SF8 QOL questionnaire was composed of the physical com- ponent score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS) and included 8 items. Similar to the FSSG, the scores were compared for each item between before and after starting (at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks) the quit smoking pro- gram. Patients in the quit smoking program were initially prescribed varenicline tartrate. In patients who could not tolerate varenicline tartrate, it was changed to Nicotine Patch. Varenicline tartrate was taken at a daily dose of 1 tablet containing 0.5 mg from day 1 to 3, 1 tablet twice a day from day 4 to 7, and 2 tablets containing 1 mg in each twice a day thereafter. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation in patients’ characteristics and QOL scores, and mean ± standard error in FSSG scores. Data were analyzed with the Wilcoxon test. Physicians explained in detail the purpose of this study to each patient and obtained in- formed consent from them. 3. RESULTS Thirty-three patients in the 12-week quit smoking pro- gram were enrolled in the present study. There were 22 males and 11 females. Their age was 54.8 ± 13.0 yr, BMI was 22.9 ± 4.0. Duration of smoking was 33.5 ± 12.5 years and number of daily smoked cigarettes was 26.0 ± 11.9/day. The Brinkman index was 902.6 ± 561.4. The Brinkman index was calculated by multiplying the number of years of smoking and the number of daily smoked cigarettes. Seventeen patients received vareni- cline tartrate, while the other 16 patients were switched to a nicotine patch. Regarding underlying disease, 2 pa- tients suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary dis- ease, 3 patients suffered from asthma and 2 patients suf- fered from hypert ensi o n. Figure 1. Frequency Scale for the Symptom of GERD (FSSG) questionnaire is diagnostic tool of GERD consisting of 12 items that are most commonly being complained by GERD patients and it has 7 questions related to reflux symptoms and 5 questions related to ysmotility symptoms. d  K. Nakajima et al. / Health 3 (2011) 677-6 83 679679 Four of the 33 patients were excluded from the analy- sis d 2 weeks (2.3 ± 0.7, p < 0.01), 4weeks (3.0 ± 0.7, p < ue to missing data in the baseline FSSG question- naire. Of the remaining all 29 patients succeeded in quit smoking. Patients who did not fill out the FSSG ques- tionnaires completely were excluded from the analysis of TS, DS, and RS. Data analyses on TS, DS, and RS were performed on 22 patients at 2 weeks, 25 patients at 4weeks, 23 patients at 8 weeks, and 23 patients at 12 weeks. Evaluation of the responses to each questions of the FSSG was performed on individual patients who answered each question at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. In the FSSG before quit smoking, bloat, feeling heavy in the stomach after meals, unpleasant sensation in the throat, and burps were commonly complained as 50% or more of the patients as shown in Figure 2. Regardless severity of smoking habit (duration of smoking, the number of daily smoked cigarettes and Brinkman index), GERD symptoms after quit smoking were improved. TS at baseline was 8.6 ± 1.8, and significant im- provement was seen at 2 weeks (4.7 ± 1.6, p < 0.01), 4 weeks (5.7 ± 1.3, p < 0.01), 8 weeks (4.5 ± 1.4, p < 0.05) and 12 weeks (3.7 ± 1.2, p < 0.01) compared with that at baseline (Figure 3(a)). RS at baseline was 4.2 ± 0.9, and significant improvement was seen at 2 weeks (2.5 ± 0.9, p < 0.01), 4 weeks (2.6 ± 0.6, p < 0.05), 8 weeks (2.2 ± 0.8, p < 0.05) and 12 weeks (1.7 ± 0.6, p < 0.01) com- pared with that at baseline (Figure 3(b)). DS at baseline was 4.5 ± 0.9, and significant improvement was seen at 0.05), 8 weeks (2 .3 ± 0.8, p < 0.05) and 12 weeks (2.0 ± 0.7, p < 0.01) compared with that at baseline (Figure 3(c)). In this program, 15 received varenicline tartrate and the other 14 patients received a nicotine patch be- cause of intolerance to varenicline tartrate. However, as for FSSG score, there was no significant difference be- tween varenicline tartrate and nicotine p atch group at the end of this program. Regarding the change of scores of each item in FSSG, all items in the FSSG except for Q8 (“feel full while eating meals”) and Q9 (“stuck”) significantly improved during the program. Particularly, significant improve- ments were observed in Q3 (“feel heavy after meals”), Q7 (“unusual sensation in the throat”), Q10 (“acid into the throat”), and Q11 (“burp”) at only 2 weeks after starting the program and thereafter (Figure 4). Since cutoff score of FSSG is 8 points [6], we ana- lyzed GERD subgroup (n = 10) whose score >8. TS at baseline was 18.0 ± 2.9, and significant improvement was seen at 8weeks (7.6 ± 2.9, p < 0.05), 12 weeks (7.1 ± 2.9, p < 0.05) compared with that at baseline (Figure 5(a)). RS at baseline was 8.9 ± 1.6, and significant im- provement was seen at 12 weeks (3.2 ± 1.6, p < 0.05) compared with that at baseline (Figure 5(b)). DS at baseline was 9.1 ± 1.5, and significant improvement was seen at 8weeks (3.5 ± 1.5, p < 0.05) and 12 w eeks (3.9 ± 1.5, p < 0.05) compared with that at baseline (Figure 5(c)). Figure 2. Distributions of FSSG score at baseline. In the FSSG before quit smoking, bloat, feeling heavy in the stomach after meals, unusual sensation in the throat, and burps were commonly com- plained as 50% or more of the patients. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/  K. Nakajima et al. / Health 3 (2011) 677-6 83 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 680 Figure 3. Change of FSSG-Total score (TS) by quit smoking program (a) upper panel. TS showed significant improvemen 8 QOL score was 47.3 ± 5.4/48.9 ± 6.6 at baseline, 50.6 ± 4.9*/51.1 ± n rapidly absorbed into the body of nic- otine-naïve people, acts on parasympathetic ganglions as ings, resulting in stimula- tio t at 2 weeks (p < 0.01), 4 weeks (p < 0.01) 8 weeks (p < 0.05) and 12 weeks (p < 0.01) compared with that at baseline, re- spectively. Change of FSSG-Reflux score (RS) by quit smok- ing program (b) middle panel. RS showed significant im- provement at 2 weeks (p < 0.01), 4weeks (p < 0.05) 8 weeks (p < 0.05) and 12 weeks (p < 0.01) compared with that at baseline, respectively. Change of FSSG-Dysmotility score (DS) by quit smoking program (c) lower panel. DS showed significant im- provement at 2 weeks (p < 0.01), 4 weeks (p < 0.05) 8 weeks (p < 0.05) and 12 weeks (p < 0.01) compared with that at base- line, respectively. 6.7 at 2 weeks, 51.2 ± 4.7**/51.1 ± 4.6* at 4 weeks, 51.3 ± 5.8**/50.7 ± 5 As shown in Figure 6, PCS/MCS in SF .2 at 8 weeks and 50.6 ± 5.6*/50.2 ± 7.0 at 12 weeks, respectively (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs. baseline). PCS showed significant improvements at 2 to 12 weeks after quitting smoking compared with those at baseline, while MCS improved at 4 weeks. There was no significant difference in PCS/MCS score between vare- nicline tartrate and nicotine patch group at the end of this program. 4. DISCUSSION Nicotine, whe well as cholinergic nerve end n of peristaltic movement of the GI tract and thus bringing on nausea and diarrhea [7]. In contrast, chronic long-term ingestion of nicotine alters the peristaltic movement of the GI tract, influences the function of multiple endocrine organs, and injures defense mecha- nisms of the GI tract [8]. It also induces the release of mediators as well as hormones that affect the structural integrity of the epithelium and mucosa [9,10]. Further- more, reducing LES pressure may result in symptom generation of GERD [11]. Kahrilas PJ et al. described that the mechanisms of acid reflux during cigarette smoking were mainly dependent on the coexistence of diminished LES pressur e and the majority of acid reflux occurred with cough ing o r d eep in spiration d uring wh ich abrupt increases in intra-abdominal pressure overpow- ered a feeble sphincter rather than transient LES relaxa- tion [12]. Accordingly, cigarette smoking may correlate GE RD s ymptom through various mechanisms. Kusano et al. [6] reported the FSSG to evaluate GERD symptoms. They reported that it showed a sensi- tivity of 62%, specificity of 59%, and accuracy of 60% when the cscore was set at 8 points and Futoff SSG is widely used to evaluate GERD symptoms thereafter [13-15]. In this study, mean score of FSSG before start- ing the program was 8.6 and 30% of patients was equal or more than 8 points. According to the recent review form Japan, ratio of GERD was reported as 1.3 to 13.7% in general population [16]. Although the patient number of this study is a few, ratio of GERD might be more fre- quent than expected among smokers. Intervention stud- ies with patients with GERD symptoms, RS and DS are ameliorating associated with PPI administration [17,18]. Consequently, the FSSG is useful for evaluation of GERD symptoms and therapeutic effect. GERD consists of three concept, which are reflux esophagitis (RE) with symptoms, reflux symptoms with- out RE and RE without symptoms [16]. Upper GI endo-  K. Nakajima et al. / Health 3 (2011) 677-6 83 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 681681 Figure 4. Change of scores of each item in FSSG, all items in the FSSG except for “feel full while eating meals” and “stuck when you swallow” significantly improved during the program. Particularly scopy is nece hysicians who don’t have endoscopic equipment should , significant improvements were observed in “feel heavy after meals”, “unusual sensation in the throat”, “acid into the throat” and “burp” at only 2 weeks after starting the program and thereafter. ssary to diagnose RE, however, general p deal with GERD patients. Therefore, some study was focused on uninvestigated GERD, which is diagnosed by symptoms [17,19]. Indeed, GERD management guide- line which was published by The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology described that initial therapy could be performed without endoscopy for patient with GERD symptoms [20]. Accordingly, control of GERD symp- toms should be clinical significance regardless endo- scopic findings. TS, RS, and DS were improved in all patient in this study (Figure 3). Surprisingly, GERD subgroup whose FSSG scor e >8 reveled that FSSG score significantly improved at 12 week (Figure 5). Among these patients group, 12.5%, 11.0% ,33.3% and 40.0% of these recognized complete symptom relief at 2, 4, 8 and 12 week respectively. These result suggested that quit smoking may be an option of treatment of GERD symp- toms, or at least lead of quit smoking for patients with GERD symptom could have additive therapeutic effect. Quit smoking, as evaluated with the FSSG, improved the following GERD symptoms promptly only 2 weeks; “f g also allevi- ated the “unusual sensation in your throat” in a short uld benefit from quit smoking in terms of lt as these pr eeling heavy after meals”, “acid in the throat” and “burp”. This was because quit smoking might improve the nicotine-induced decline in esophageal lower sphincter pressure, which had led to frequent occurrence period of time in this study. Chang-Chun Lin et al. [21] and Belafsky P.C. et al. [22] pointed out in their studies using RSI (reflux symptom indexes) scores that smoking provoked symptoms related to the vocal cord or the laryngopharynx. Therefore, quit smoking seemed to ease such symptoms. Our result indicated that improvement of GERD symptoms brought about by quit smoking was not re- lated to Brinkman index. Hence, it seems that even a heavy smoker wo of reflux symptoms [3,11,12]. Quit smokin improvement of GERD symptoms. There are reports that indicated that quit smoking im- proved self-control and health transition and that quit smoking improved the QOL of asthmatic ex-smokers [23,24]. In this study showed the similar resu evious studies. Especially, PCS kept improving sig- nificantly during the program. Moreover, both PCS and MCS exceeded 50 points which is mean Japanese na- tional level after starting the program at only 2 weeks and maintained until the end of program. In this study, quit smoking led prompt improvement in some symp- toms, might direct impact on QOL particularly PCS which is concerning physical health. In this study, it is unclear whether patients had reflux  K. Nakajima et al. / Health 3 (2011) 677-6 83 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 682 Figure 5. Change of FSSG-Total score (TS) by quit smoking program among GERD subgroup (a) upper panel. TS showed significant improvement at 8weeks (p < 0.05) and 12 weeks < 0.05) compared with that at baseline, respectively. Change of (p FSSG-Reflux score (RS) by quit smoking program among GERD subgroup (b) middle panel. RS showed significant im- provement at 12 weeks (p < 0.05) compared with that at base- line, respectively. Change of FSSG-Dysmotility score (DS) by quit smoking program among GERD subgroup (c) lower panel. DS showed significant improvement at 8 weeks (p < 0.05) and 12 weeks (p < 0.05) compared with that at baseline, respec- tively. Figure 6. Change of SF8 QOL by quit smoking program. Physical component summary (PCS) significant improved at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks versus baseline. Mental component sum- mary (MCS) significant improved at 4 weeks versus baseline Both PCS and MCS exceeded 50 points promptly after starting t. Moreover, it remains to be studied whether y: Lower oeso- implications. Lancet, 7853, 347-349. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(74)93088-8 . the program at only 2 weeks and maintained until the end of program. esophagitis or peptic ulcer since we did not perform an endoscopy. We focused on change of “symptoms” of GERD by quit smoking program and revealed its im- rovemenp quit smoking induced improvement of symptoms is maintained for a long period of time since our follow-up period was short. These points are limitation of this study. We hope that a large-scale long-term study will be conducted in the future. In Conclusions, Quit smoking improved not only GERD symptoms but also QOL. We showed that quit smoking has the poten tial of being one of the therap eutic strategic options for GERD symptom treatment. 5. CONFLICT OF INTEREST There is no conflict of interest. REFERENCES [1] l Surve Salter, R.H. (1974) Occasiona phageal sphincter. Therapeutic Bennett, J.R. (1972) Smoking and l reflux. British Medical Jounal, 30, [2] Stanciu, C. and Gstroo-oesophagea 793-795.doi:10.1136/bmj.3.5830.793 [3] Chattopadhyay, D.K., Greaney, M.G. and Irvin, T.T. (1977) Effect of cigarette smoking on the lower oeso- phageal sphincter. Gut, 18, 833-835. doi:10.1136/gut.18.10.833 [4] Gritz, E.R., Carr, C.R. and Marcus, A.C. (1991) The . (2003) Stopping pation. Addiction, 98, 1563- tobacco withdrawal syndrome in unaided quitters. British Journal of Addiction, 86, 57-69. [5] Hajek, P., Gillison, F. and McRobbie, H smoking can cause consti  K. Nakajima et al. / Health 3 (2011) 677-6 83 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 683683 1567. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00497.x [6] Kusano, M., Shimoyama, Y., Sugimoto, S., et al. (2004) Development and evaluation of FSSG: frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD. Journal of Gastroenterology, 39, 888-891. doi:10.1007/s00535-004-1417-7 [7] Massarrat, S. (2008) Smoking and Gut. Archives of Ira- d secretin ffects of prostaglandins d East- ., van Leeuwen, J.A., Schoots, I.G. ) Mechanisms of acid nian Medicine, 11, 293-305 [8] Murthy, S.N., Dinosi, V.P. Jr, Clearfield, H.R. and Chey, W.J. (1977) Simultaneous measurement of basal pancre- atic, gastric acid secretion, plasma gastrin, an during smoking. Gastroenterology, 73, 758-761. [9] Miller, T.A. (1983) Protective e against gastric mucosal damage: current knowledge and proposed mechanisms. American Journal of Physiology, 245, G601-G623. [10] Quimby, G.F., Bonnice, C.A., Burstein, S.H. an wood, G.L. (1986) Active smoking depresses pros- taglandin synthesis in human gastric mucosa. Annals of Internal Medicine, 104, 616-619. [11] Smi,t C.F., Copper, M.P and Stanojcic, L.D. (2001) Effect of cigarette smoking on gastropharyngeal and gastroesophageal reflux. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology, 11 0, 190-193. [12] Kahrilas, P.J., Gupta, R.R. (1990 reflux associated with cigarette smoking. Gut, 31, 4-10. doi:10.1136/gut.31.1.4 [13] Miyamoto, M., Haruma, K., Takeuchi, K. and Kuwabara, M. (2008) Frequency scale for symptom of gastroe- f epatology, 23, 746-751. sophageal reflux disease predicts the need for addition of prokinetics to proton pump inhibitor therapy. Journal o Gastroenterology and H doi: 10 .1111 /j .1440-1746.2007.05218.x [14] Oridate, N., Takeda, H., Mesuda, Y., et al. (2008) Evalua- tion of upper abdominal symptoms using the Frequency Scale for the Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflu toms. Journal of Gastroenterology, 43, 5x symp- 19-523. doi:10.1007/s00535-008-2189-2 [15] Danjo, A., Yamaguchi, K., Fujimoto, K., et al. (2009) Comparison of endoscopic findings with symptom as- sessment systems (FSSG and QUEST) for gastroe- sophageal reflux disease in Japanese centres. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 24, 633-638. doi: 10 .1111 /j .1440-1746.2008.05747.x [16] Fujiwara, Y. and Arakawa, T. (2009) Epidemiolo clinical characteristics of GERD in the gy and Japanese popula- tion. Journal of Gastroenterology, 44, 518-534. doi:10.1007/s00535-009-0047-5 [17] Nagahara, A., Asaoka , D., Hojo, M., et al. (2010 vational comparative trial of the ef) Obser- ficacy of proton pump inhibitors versus histamine-2 receptor antagonists for uninvestigated dyspepsia. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 25, S122-128. doi: 10 .1111 /j .1440-1746.2009.06218.x [18] Hongo, M., Miwa, H., Kusano, M., J-F Effect of rabeprazole treatment on heal AST group. (2011) th-related quality of life and symptoms in patients with reflux esophagitis: a prospective multicenter observational study in Japan. Journal of Gastroenterology, 46, 297-304. doi:10.1007/s00535-010-0342-1 [19] Thomson, A.B., Barkun, A.N., Armstron (2003) The prevalence of clinicallyg, D., et al. significant endo- scopic findings in primary care patients with uninvesti- gated dyspepsia: the Canadian Adult Dyspepsia Empiric Treatment—Prompt Endoscopy (CADET-PE) study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 17, 1481- 1491.doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01646.x [20] The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology. GERD man- agement guideline. (2009) The Japanese Society of Gas- ngeal symptoms with troenterology, Tokyo,(in Japanese) [21] Lin, C.C., Wang, Y.Y., Wang, K.L., et al. (2009) Associa- tion of heartburn and laryngophary endoscopic reflux esophagitis, smoking, and drinking. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 141, 264-271. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.05.017 [22] Belafsky, P.C., Postma, G.N. and Koufman, J.A. (2002) Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). Journal of Voice, 16, 274-277. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00097-8 [23] Hays, J.T., Croghan, I.T., Baker, C.L. and Bushmakin, AG. (2010) Change , Cappelleri, J.C. s in health-related quality of life with smoking cessation treatment. Eur J Public Health. 30 September 2010. [Epub ahead of print] [24] Jang, A.S., Park, S.W., Kim, D.J., et al. (2010) Effects of smoking cessation on airflow obstruction and quality of life in asthmatic smokers. Allergy, Asthma and Immu- nology Research, 2, 254-259. doi:10.4168/aair.2010.2.4.254

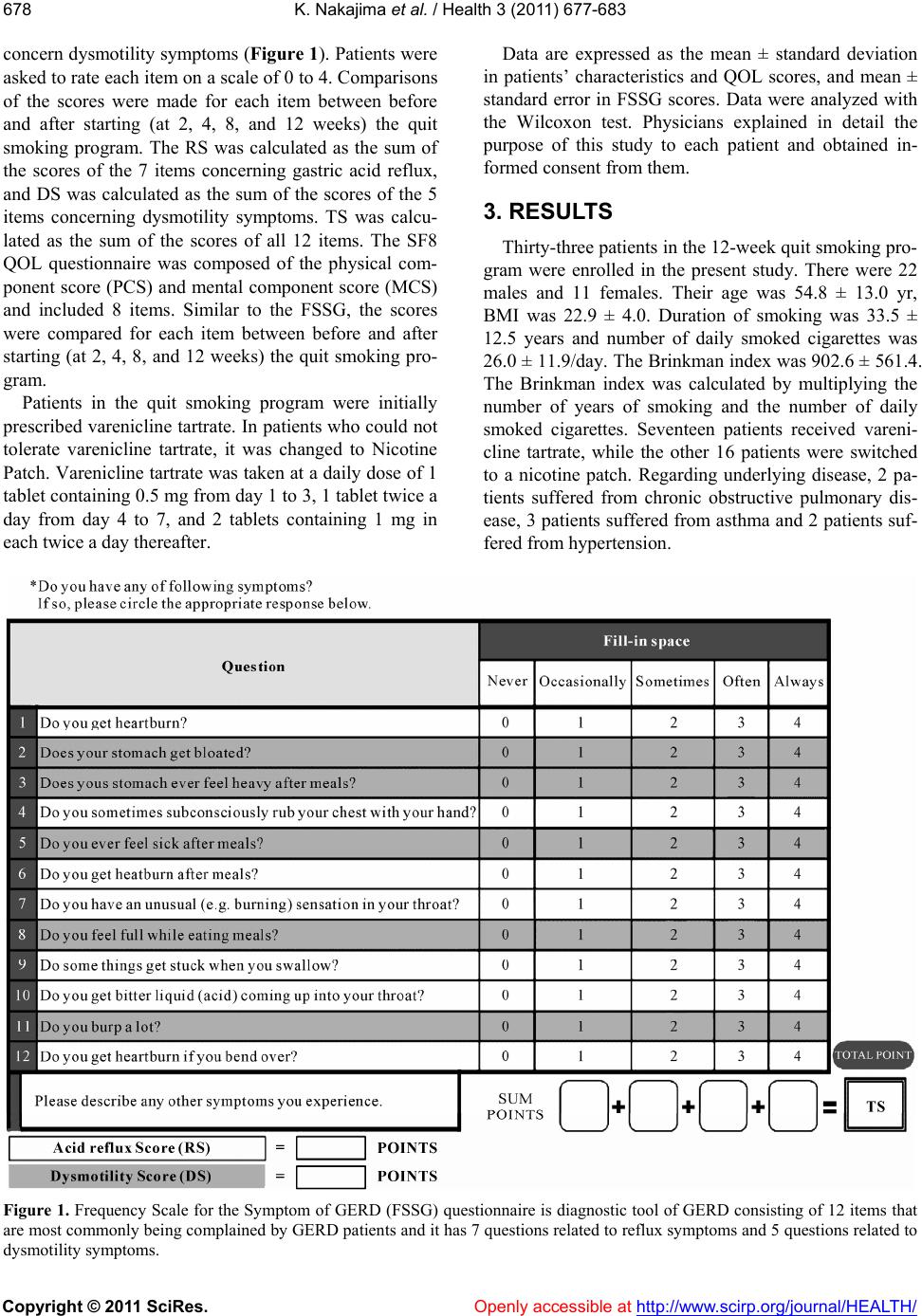

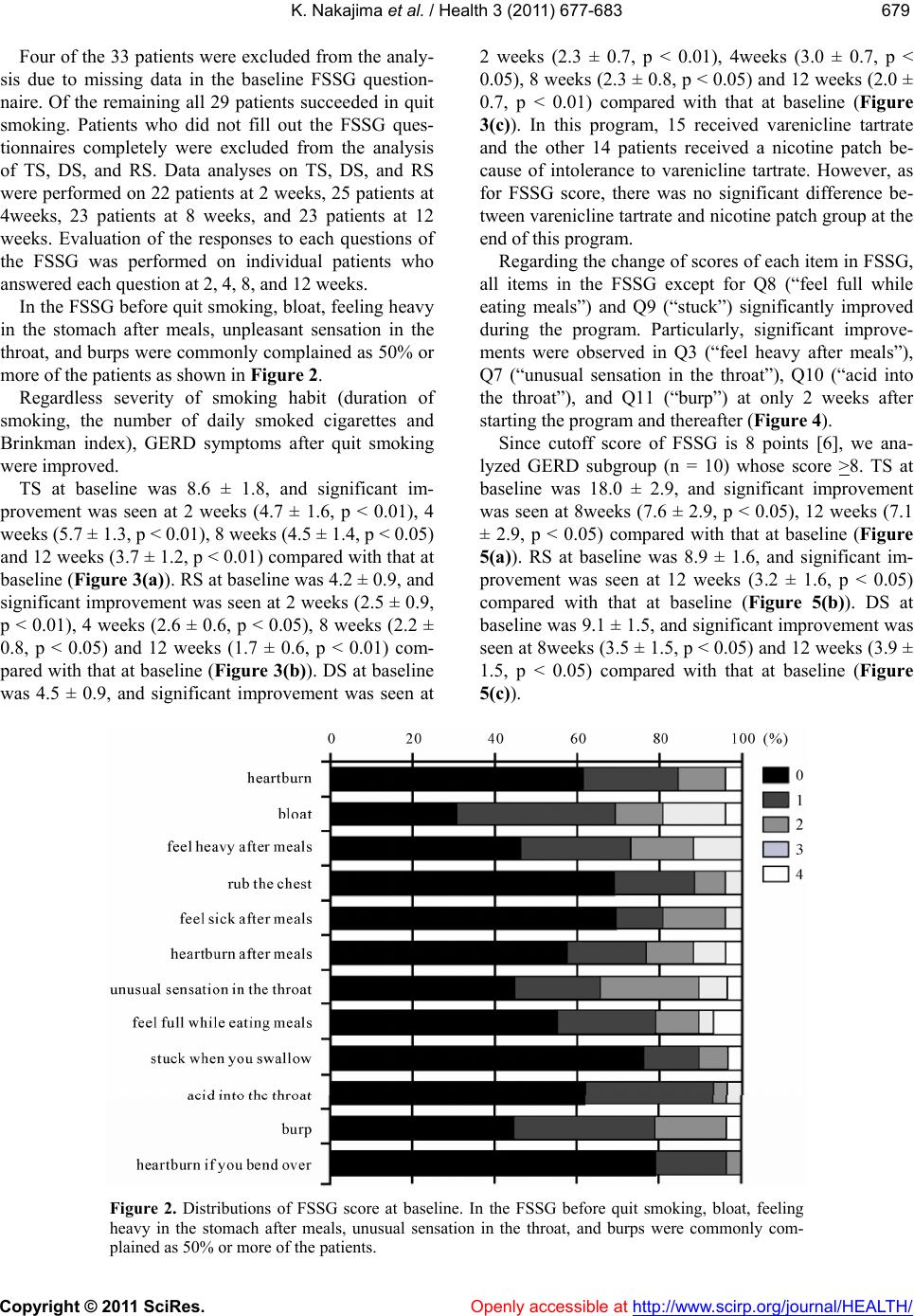

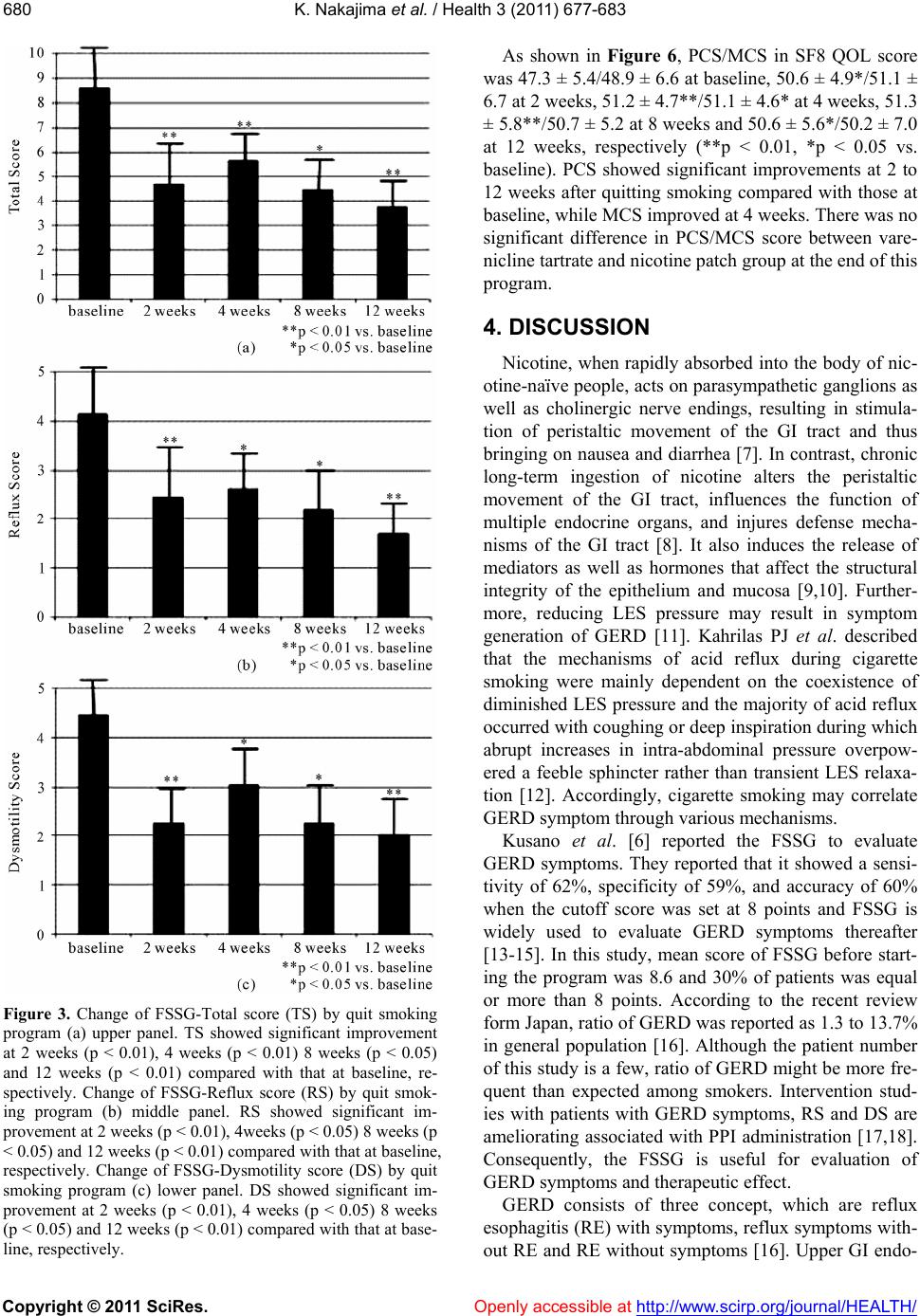

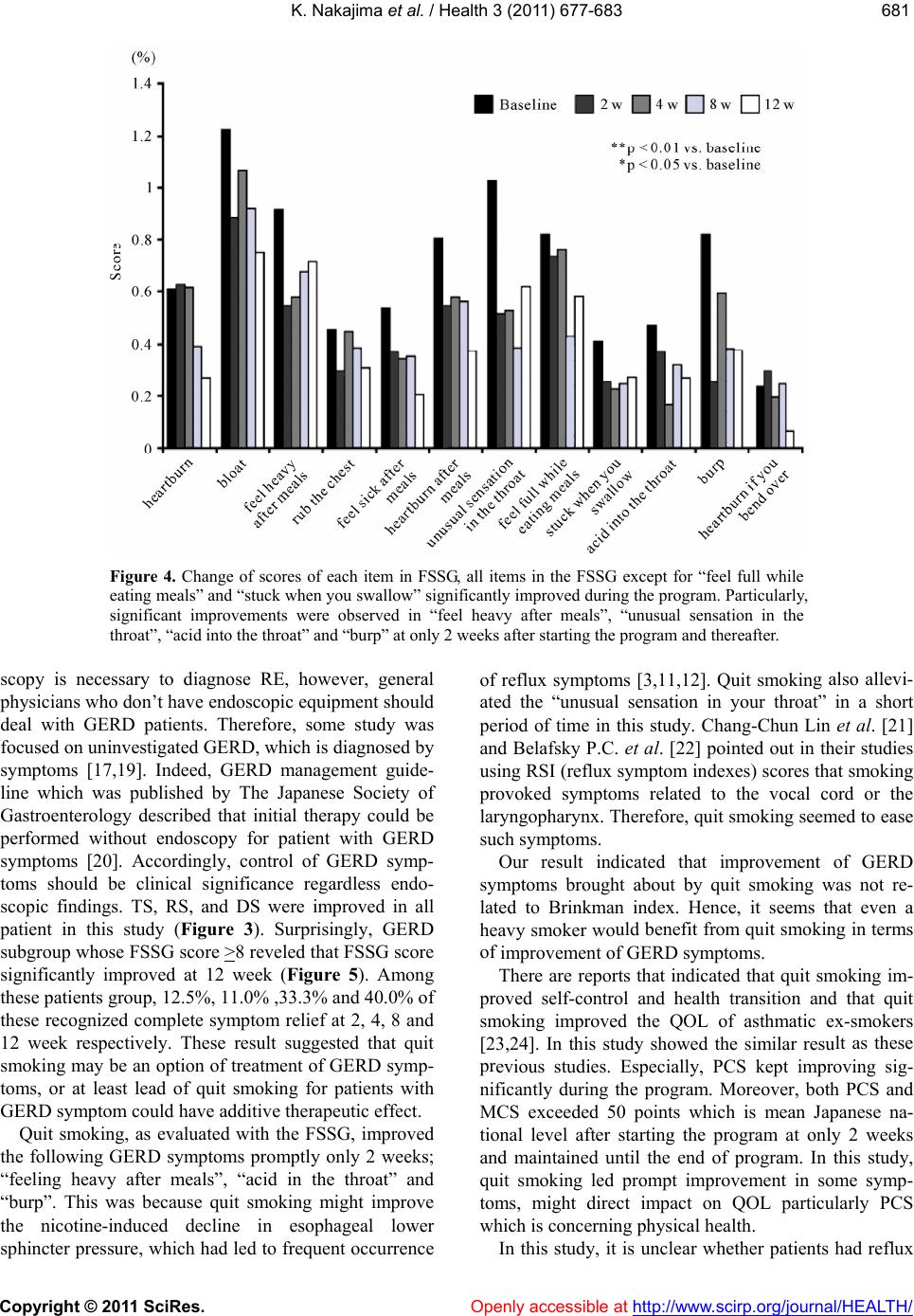

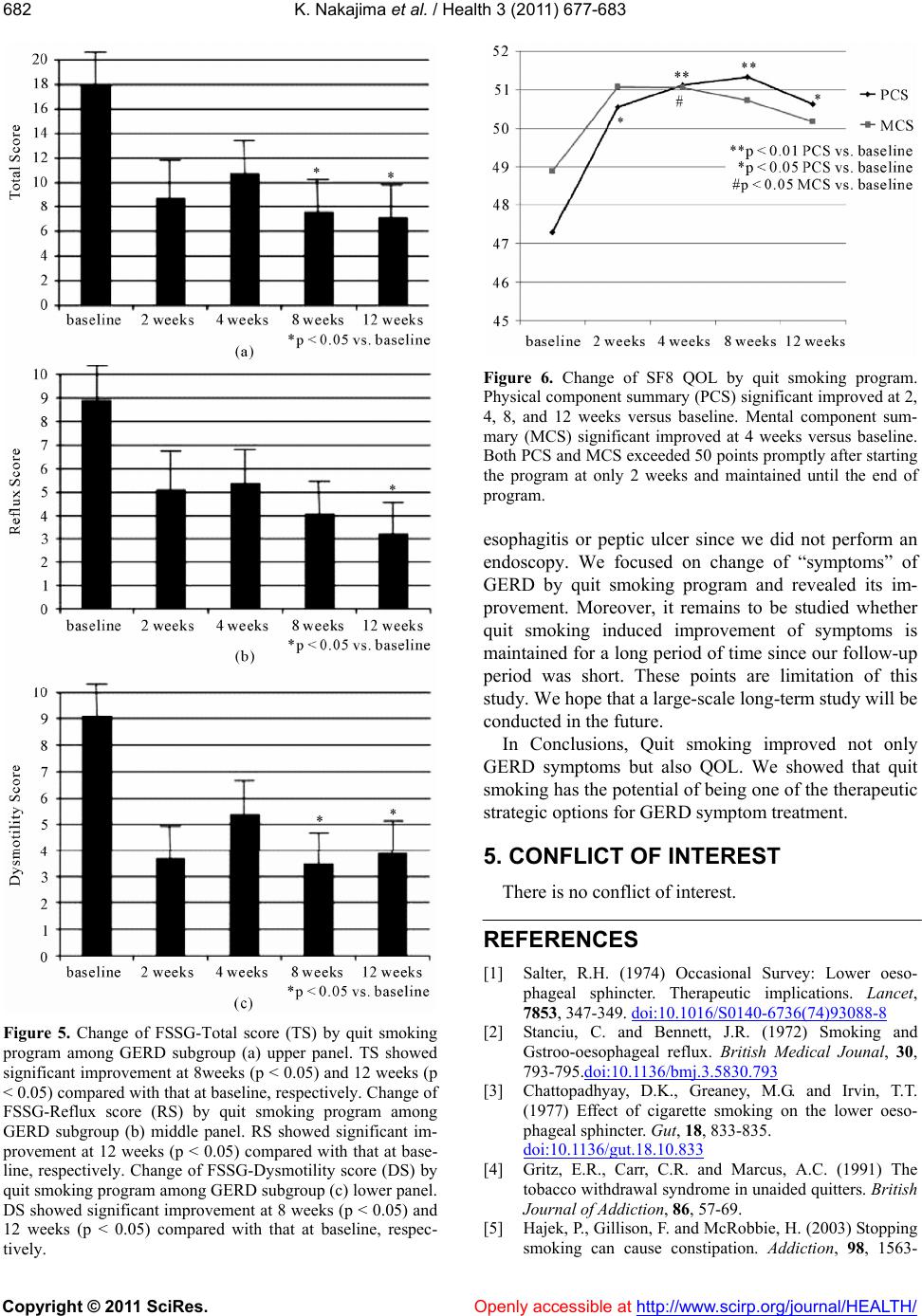

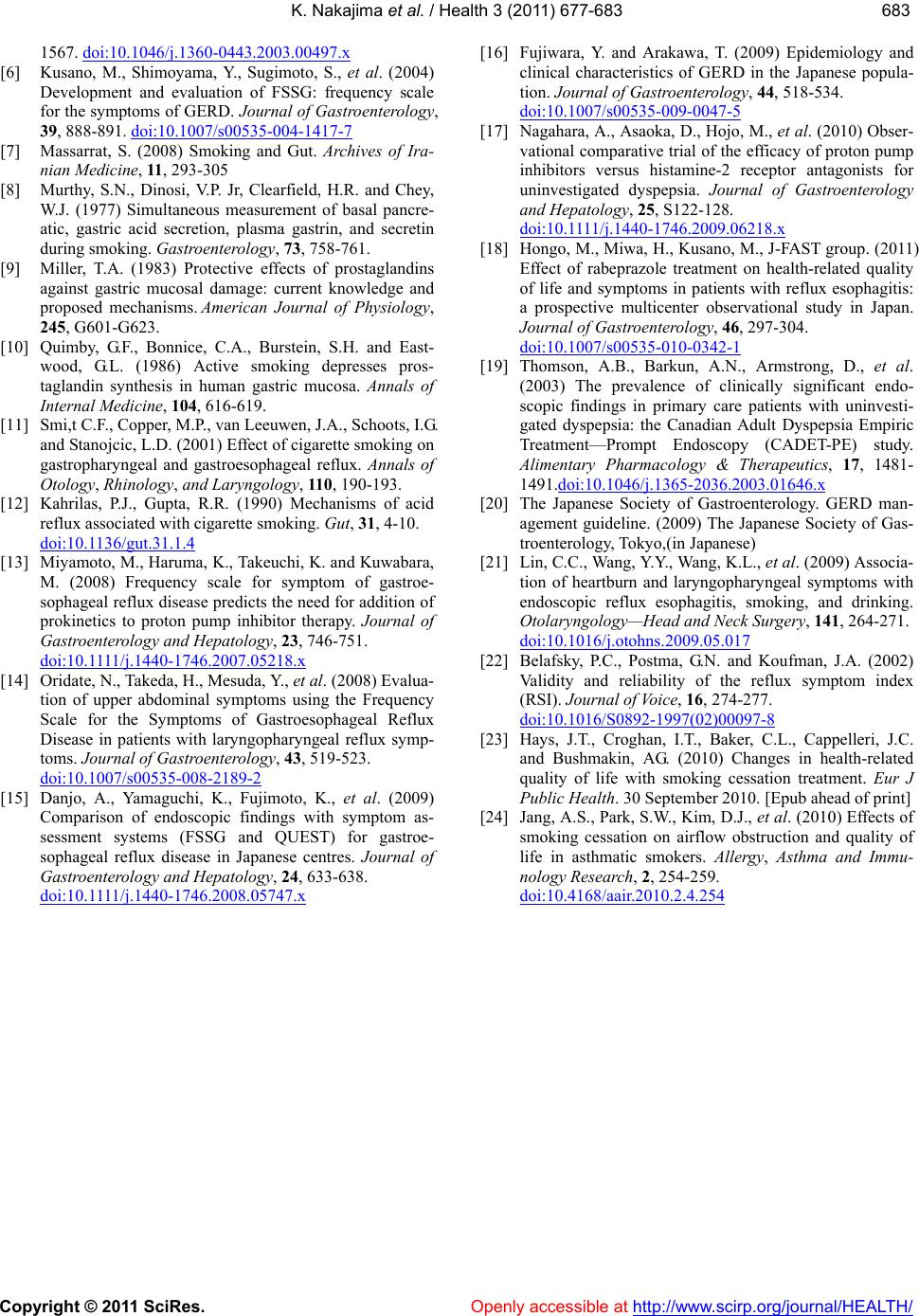

|