Vol.1, No.3, 101-108 (2011) doi:10.4236/ojpm.2011.13015 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ Open Journal of Preventive Medicine Personality characteristics and health risk behaviors associated with current marijuana use among college students Carla J. Berg1*, Taneisha S. Buchanan2, Linda Grimsley3, Jan Rodd3, Daniel Smith4 1Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Emory University School of Public Health, Atlanta, USA; *Corresponding Author: cjberg@emory.edu 2Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA; 3Department of Nursing, Albany State University, Albany, USA; 4Institutional Effectiveness, Athens Technical College, Athens, Greece. Received 7 September 2011; revised 16 October 2011; accepted 26 October 2011. ABSTRACT Objective: Marijuana is a prevalent substance used among young adults and has serious psy- cho soc ia l and he alth-rel ate d co nsequenc es . Thus, identifying factors associated with marijuana use is critical. The current study aimed to exa- mine personality factors and health risk be- haviors associated with marijuana use. Methods: We administered an online survey to six col- leges in the Southeast. Overall, we recruited 24,055 college students, yielding 4840 respon- ses (20.1% response rate), with complete data from 4,401 students. Results: Current (past 30 day) marijuana use was reported by 13.8% of our sample. Users either reported infrequent use of marijuana (i.e., between 1 and 5 days; 52.3%) or very frequent use of marijuana (i.e., between 26 and 30 days; 18.2%). Mutlivariate analyses modeling correlates of marijuana use (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.323) indicated that signifi- cant factors included being younger (p < 0.001), being male (p = 0.002), being Black (p = 0.002), attending a fou r-year college (p = 0 .00 5) , b eing a nondaily (p < 0.001) or daily smoker (p < 0.001) vs. a nonsmoker, other tobacco use (p < 0.001), greater alcohol use (p < 0.001), greater per- ceived stress (p = 0.009), higher levels of sen- sation seeking (<0.001) and openness to ex- periences (p = 0.02), and lower levels of agree- ableness (p = 0.01) and conscientiousness (p < 0.001). Conclusions: Identifying risk factors re- lated to marijuana use is critical in developing intervent ions targeti ng both use and prev ention. Moreover, understanding different college set- tings and the contextual factors associated with greater marijuana use is critical. Keywords: Marijuana Use ; Toba cco ; A lcoh ol U se; College Students 1. INTRODUCTION Marijuana has been the most common illicit substance used in the United States for several decades [1,2]. It is especially common among young adults, with approxi- mately 16% of young adults (ages 18 to 25) having used marijuana within the past month [1]. In addition, as many as 9.4% of college freshman may have a marijuana use disorder [3], and about 35% of users meet at least one criterion for marijuana dependence [4]. Marijuana use has several important negative implica- tions. In terms of morbidity and mortality, marijuana use plays a major role in motor vehicle crashes [5], has ad- verse effects on the respiratory and cardiovascular sys- tems [6-10], increases susceptibility to cancer [11], and impairs short- and long-term memory functioning [12]. Not only are there health consequences, but marijuana use has important psychosocial effects. Marijuana use is associated with impaired poor school performance, low educational aspirations and expectations [13,14], low educational attainment [15], reduced workplace produc- tivity [16], and the postponement of marriage and em- ployment [17]. Certain intra-individual characteristics are related to marijuana use [18]. For example, one longitudinal study over a 23 year span from early adolescence to adulthood [13] found that chronic marijuana use was associated with poor self-control [13], more externalizing behavior [19], and greater sensation seeking [13]. Higher levels of depressive symptoms have also been found to prospec- tively predict different trajectories of marijuana use  C. J. Berg et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 (2011) 101-108 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 102 through adolescence [20]. In addition, stress has been a factor associated with using marijuana [21]. Moreover, marijuana use has been correlated with other problem behaviors, such as rebelliousness [22], delinquency [22], and risky sexual behavior [22]. It is also associated with an increased risk of use of other substances [22,23], in- cluding cigarette smoking [1,24] and alcohol use [1,24]. Given the aforementioned literature, the present study aimed to examine correlates of marijuana use in a sam- ple of Southeast U.S. college students. Specifically, we examined sociodemographics (age, gender, race, paren- tal education, and type of school attended), other health risk behaviors (cigarette smoking, other tobacco use, alcohol use, sexual activity), and psychosocial correlates (depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and personality traits including sensation seeking, extraversion, agree- ableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and open- ness to experience) in relation to marijuana use. 2. METHODS In October, 2010, students at six colleges in the Southeast were recruited to complete an online survey. A random sample of 5000 students at each school (with the exclusion of two schools who had enrollment less than 5000) were invited to complete the survey (total invited N = 24,055). Students received an e-mail con- taining a link to the consent form with the alternative of opting out. Students who consented to participate were directed to the online survey. To encourage participation, students received up to three e-mail invitations to par- ticipate. As an incentive for participation, all students who completed the survey received entry into a drawing for cash prizes of $1000 (one prize), $500 (two prizes), and $250 (four prizes) at each participating school. Of students who received the invitation to participate, 4840 (20.1%) returned a completed survey. Our current a- nalyses focus on 4401 participants who had complete data. The vast majority of our sample (95.1%) was be- tween the ages of 18 and 30 years old, with the oldest participant being 48 years of age. The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved this study, IRB# 00030631. 2.1. Measures An online survey containing 230 questions assessed a variety of health topic areas, which took approximately 20-25 minutes to complete. For the current investigation, only the following variables were included. Demographic characteristics assessed included stu- dents’ age, gender, ethnicity, highest parental educa- tional attainment, and type of school attended (i.e., two- year versus four-year college). Ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic White, Black, or Other due to the small numbers of participants who reported other race/ethnici- ties. Highest parental educational attainment was cate- gorized as high school graduate or GED, some college, or ≥ Bachelors degree based on the distribution of pa- rental educational attainment. For ease of interpretation, these categorizations were chosen. Current Marijuana Use. To assess current marijuana use, students were asked, “In the past 30 days, on how many days did you use marijuana (pot, weed, hashish, hash oil)?” (ACHA, 2008; CDC, 1997). Current users were considered to be individuals who smoked at least one day in the past 30 days. Smoking Status. To assess smoking status, students were asked, “In the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke a cigarette (even a puff)?” This question has been used to assess tobacco use in the American College Health Association (ACHA) surveys, National College Health Risk Behavior Survey (NCHRBS), and Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), and their reliability and validity have been documented by previous research [25,26]. Students who reported smoking on at least one day in the past 30 days were considered current smokers, and students who reported smoking on all 30 days of the past month were considered daily smokers versus non- daily smokers (i.e., those who smoked from 1 to 29 days of the past 30 days). This is consistent with how ACHA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Association (SAM- SHA), and others have defined “daily smokers” [27,28]. Other Tobacco Use. To assess other tobacco use, stu- dents were asked, “In the past 30 days, on how many days did you: Use chewing tobacco, snuff, or dip, such as Redman, Levi Garrett, Beechnut, Skoal, Skoal Ban- dits, or Copenhagen? Smoke cigars (Please do not in- clude little cigars or cigarillos, such as Black and Milds, when answering this question)? Smoke little cigars (such as Black and Milds)? Smoke cigarillos (such as Swisher Sweets cigarillos)? Smoke tobacco from a water pipe (hookah)?” An aggregate variable for any other tobacco use in the past month was created. Alcohol Use. To assess alcohol use, students were asked, “In the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink alcohol?” (ACHA, 2008; CDC, 1997). Number of Sexual Partners. Participants were asked, “During the past 12 months, with how many people did you have sexual intercourse?” Depressive Symptoms. Participants were asked to complete the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) [29], which is a 2-item depression screening tool, based on DSM-4 diagnostic criteria, assessing frequency of de- pressed mood (“feeling down, depressed or hopeless”) and anhedonia (“little interest or pleasure in doing things”) over the past two weeks. Responses were rated  C. J. Berg et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 (2011) 101-108 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 103 on a 4-point Likert scale and range from “not at all” (0) to “nearly every day” (3). A total score > 3 has been used to reflect clinical depression [29]. Using a mental health professional interview as the criterion standard, a PHQ-2 score ≥ 3 had a sensitivity of 83% and a specific- ity of 92% for major depression, indicating that a PHQ-2 score of 3 is the optimal cutpoint for screening purposes. Perceived Stress. Participants completed the Per- ceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) [30] to assess the amount of stress they experienced in the past month. Higher total scores indicate greater levels of perceived stress. Sensation Seeking. The Brief Sensation Seeking Scale —4 item (BSSS-4) [31] is an abbreviated version of the 8-item Brief Sensation Seeking Scale. The BSSS-4 in- cludes the items from the BSSS after examining the psychometric properties of the BSSS [32] and retaining one item from each of the four original subscales with the highest item-total correlation. The four items are: a) I would like to explore strange places; b) I like to do frightening things; c) I like new and exciting experiences, even if I have to break the rules; and d) I prefer friends who are exciting and unpredictable. Psychometric analy- ses revealed appropriate internal consistency (Cronbach alpha of 0.75), convergent validity, and test-retest reli- ability [31]. Big 5 Personality Traits. The Ten-Item Personality In- ventory (TIPI) [33] is a brief measure that assesses cha- racteristics included in traditional Big Five personality inventories (i.e., Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscien- tiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experi- ence), two items measuring each factor. Each item con- sists of two descriptors, separated by a comma, using the common stem, ‘‘I see myself as:’’. Each of the five i- tems was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (dis- agree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). The TIPI takes a- bout a minute to complete. This measure has demon- strated appropriate internal consistency for two-item scales (Cronbach alphas of 0.68, 0.40, 0.50, 0.73 and 0.45 for the Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscien- tiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experi- ence scales respectively). Although somewhat inferior to standard multi-item instruments, the TIPI demonstrates adequate convergent validity, test–retest reliability, and appropriate patterns of predicted external correlates [33]. 2.2. Data Analysis Participant characteristics were summarized using de- scriptive statistics. Bivariate analyses were conducted comparing current marijuana users versus nonusers us- ing chi-squared tests for categorical variables and inde- pendent samples t-tests for continuous variables. Binary logistic regression was used to examine factors associ- ated with current marijuana use. To control for the po- tential influence of demographic characteristics on the primary outcomes of interest (i.e., marijuana use), age, gender, ethnicity were entered into each model, and then factors associated with marijuana use at the p < 0.10 were entered using backwards stepwise entry. SPSS 18.0 was used for all data analyses. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 for all tests. 3. RESULTS Current (past 30 day) marijuana use was reported by 13.8% of the sample. Figure 1 displays the frequency of use among current users. Notably, the majority (52.3%) of marijuana users reported infrequent use of marijuana (i.e., between 1 and 5 days) and a sizeable proportion (18.2%) reported daily or almost daily use (i.e., between 26 and 30 days). Bivariate analysis indicated that correlates of mari- juana use included being younger (p < 0.001), being male (p < 0.001), coming from a home with less edu- cated parents (p < 0.001), attending a four-year college (p < 0.001), being a current nondaily or daily smoker vs. a nonsmoker (p < 0.001), current other tobacco use (p < 0.001), more days of alcohol use in the past 30 days (p < 0.001), having more sex partners in the past year (p < 0.001), greater likelihood of having significant depres- sive symptoms (p < 0.001), greater perceived stress (p < 0.001), higher levels of sensation seeking (p < 0.001), and lower levels of agreeableness (p < 0.001), conscien- tiousness (p < 0.001), and emotional stability (p = 0.002; see Table 1). Mutlivariate analyses modeling correlates of mari- juana use (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.323) indicated that sig- nificant factors included being younger (p < 0.001), be- ing male (p = 0.002), being Black (p = 0.002), attending a four-year college (p = 0.005), being a nondaily (p < 0.001) or daily smoker (p < 0.001) vs. a nonsmoker, other tobacco use (p < 0.001), greater alcohol use (p < 0.001), greater perceived stress (p = 0.009), higher levels Figure 1. Frequency of marijuana use among current mari- uana users. j  C. J. Berg et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 (2011) 101-108 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/Openly accessible at 104 Table 1. Participant characteristics and bivariate analyses comparing marijuana users and nonusers. Va ri a bl e Total N = 4401 N (%) or M (SD) Nonusers N = 3795 (86.2%) N (%) or M (SD) Users N = 606 (13.8%) N (%) or M (SD) p-value Sociodemographics Age (SD) 23.52 (7.12) 23.81 (7.47) 21.74 (3.90) <0.001 Gender (%) Male Female 1267 (28.8) 3134 (71.2) 1008 (26.6) 2787 (88.9) 259 (42.7) 347 (11.1) <0.001 Ethnicity (%) White Black Other 2009 (45.6) 1714 (38.9) 678 (15.4) 1722 (45.4) 1482 (39.1) 591 (15.6) 287 (47.4) 232 (38.3) 87 (14.4) 0.60 Parental education (%) < Bachelors degree ≥ Bachelors degree 2729 (62.0) 1672 (38.0) 2401 (63.3) 1394 (36.7) 328 (54.1) 278 (45.9) <0.001 Type of school (%) Four-year Two-year 2730 (62.0) 1671 (38.0) 2292 (60.4) 1503 (39.6) 438 (72.3) 168 (27.7) <0.001 Other risk behaviors Cigarette smoking past 30 days (%) Nonsmoker Nondaily smoker Daily smoker 3358 (76.3) 594 (13.5) 449 (10.2) 3058 (80.6) 408 (10.8) 329 (8.7) 300 (49.5) 186 (30.7) 120 (19.8) <0.001 Other tobacco use past 30 days (%) No Yes 3549 (82.0) 778 (18.0) 3281 (87.8) 457 (12.2) 268 (45.5) 321 (54.5) <0.001 Alcohol use past 30 days (SD) 3.29 (5.16) 2.73 (4.68) 6.77 (6.49) <0.001 Sex partners in the past year (SD) 1.51 (3.82) 1.38 (3.97) 2.36 (2.50) <0.001 Psychosocial factors Depressive symptoms (%) No Yes 3632 (91.5) 339 (8.5) 3197 (92.3) 265 (7.7) 435 (85.5) 74 (14.5) <0.001 Perceived stress (SD) 6.17 (3.40) 6.04 (3.38) 7.01 (3.44) <0.001 Sensation seeking (SD) 3.32 (0.90) 3.26 (0.90) 3.70 (0.84) <0.001 Big 5 factors (SD) Extraversion Agreeableness Conscientiousness Emotional stability Openness 8.74 (2.87) 9.97 (2.31) 11.06 (2.43) 9.52 (2.75) 10.80 (2.31) 8.72 (2.85) 10.05 (2.30) 11.21 (2.38) 9.57 (2.74) 10.77 (2.31) 8.93 (3.02) 9.42 (2.32) 10.07 (2.53) 9.18 (2.81) 10.96 (2.29) 0.11 <0.001 <0.001 0.002 0.09 of sensation seeking (<0.001) and openness to experi- ences (p = 0.02), and lower levels of agreeableness (p = 0.01) and conscientiousness (p < 0.001; see Table 2). 4. DISCUSSION The current study documented novel findings, par- ticularly that two-year college students versus four-year college students were less likely to report current use of marijuana. Moreover, findings indicated that lower lev- els of agreeableness and conscientiousness and higher levels of openness to experiences were associated with marijuana use. Prior research documenting that marijuana use is re- lated to lower educational aspirations, expectations [13,14] and attainment [15] might suggest that four-year college students would report lower levels of marijuana use compared to two-year college students. However, we found the opposite, even after controlling for age and other characteristics. Additional research might examine qualitative differences in attitudes toward marijuana use as well as contextual factors associated with marijuana use in different college settings (e.g., technical schools, state schools, liberal arts coleges, private schools, his l  C. J. Berg et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 (2011) 101-108 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 105 Table 2. Binary logistic regression model identifying correlates of marijuana users and nonusers. Variable OR 95% CI p-value Sociodemographics Age 0.95 0.93, 0.98 <0.001 Gender Male Female Ref 0.69 -- 0.55, 0.87 -- 0.002 Ethnicity White Black Other Ref 1.52 0.89 -- 1.16, 1.98 0.63, 1.26 -- 0.002 0.51 Parental education < Bachelors degree ≥ Bachelors degree Ref 1.08 -- 0.86, 1.36 -- 0.50 Type of school Four-year Two-year Ref 0.67 -- 0.50, 0.88 -- 0.005 Other risk behaviors Cigarette smoking past 30 days (%) Nonsmoker Nondaily smoker Daily smoker Ref 1.82 3.38 -- 1.35, 2.45 1.06, 1.10 -- <0.001 <0.001 Other tobacco use past 30 days (%) No Yes Ref 4.37 -- 3.42, 5.58 -- <0.001 Alcohol use past 30 days (SD) 1.08 1.06, 1.10 <0.001 Sex partners in the past year (SD) 1.02 1.00, 1.05 0.06 Psychosocial factors Perceived stress (SD) 1.05 1.01, 1.08 0.009 Sensation seeking (SD) 1.41 1.22, 1.62 <0.001 Big 5 factors (SD) Agreeableness Conscientiousness Openness 0.94 0.88 1.07 0.89, 0.99 0.84, 0.92 1.01, 1.13 0.01 <0.001 0.02 Nagelkerke R2 = 0.323. torically black colleges and universities, tribal colleges, etc.). With regard to personality traits, lower levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness and higher levels of openness to experiences were associated with marijuana use. Although these factors are associated with sensation seeking (agreeableness: r = –0.07; conscientiousness: r = –0.05; and openness: r = 0.25), they are not highly cor- related with this well established correlate of marijuana use. Thus, these findings contribute to literature aimed at identifying individuals at risk for marijuana use and po- tential targets for intervention. Low levels of conscien- tiousness may indicate a risk for marijuana use but also poor school performance, which has been previously associated with marijuana use [13,14]. Moreover, those low in agreeableness but high in openness to experience might indicate that those less receptive to conventional societal norms may be at risk for marijuana use. The data support prior research findings indicating that marijuana use is associated with greater sensation seeking [13], higher levels of depressive symptoms [20], greater stress [21], risky sexual behavior [22], alcohol use [1,24], and cigarette smoking [1,24]. Specifically in regard to cigarette smoking, this is a concern, as concur- rent use of marijuana and tobacco is associated with in- creased symptoms of cannabis dependence [34]. Addi- tionally, both cigarette and marijuana smoke contain carcinogenic compounds [35], which could result in in- creased health risks. Finally, in the combined sample of students from two-year and four-year colleges, we found that approxi- mately 14% used marijuana within the past month, with half of these users smoking marijuana on five days or less. However, the other half used marijuana at a fre-  C. J. Berg et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 (2011) 101-108 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 106 quency equivalent to at least once a week, with one fifth of users smoking marijuana either daily or almost daily. In contrast to national data sets, this study documented a slightly lower rate of marijuana use than national sur- veys [1], which may reflect the fact that the current sam- ple was comprised of young adults attending either two- or four-year colleges. One possibility is that marijuana use may be more prevalent among non-college attending adults [13-15]. The current findings have important implications for research and practice. First, variability in marijuana use among subgroups warrants further research, as our find- ings documented a lower prevalence of marijuana use than national statistics. This may be attributed to the ge- ographic location, educational aspirations, or other cha- racteristics of the participant pool. It is critical to under- stand the underlying factors contributing to marijuana use and develop successful interventions targeting young adult marijuana use and co-occurring health risk behav- iors. In the context of college health and mental health services, providers are advised to comprehensively screen for substance use and other health risks (e.g., number of partners, safe sex practices). Health care providers should be prepared to assess the severity of substance use and determine appropriate interventions which may include stress management and addressing symptoms of depress- sion. 4.1. Limitations A number of important limitations should be consid- ered when interpreting data from this study. First, the survey sample was largely female and drawn from six Southeast colleges. Despite the fact that this sample re- flects the characteristics of these school populations and has good representation of White and Black ethnic back- grounds, it may not generalize to other college popula- tions. Second, the survey response rate was 20.1%, which may seem low and might suggest responder bias. However, previous online research has yielded similar response rates (29% - 32%) among the general popula- tion [36] and a wide range of response rates (17% - 52%) among college students [37]. We are also unable to as- certain how many participants did not open the e-mail or had inactive accounts, which impacts what the true “de- nominator” for this response rate may have been. Prior work has demonstrated that, despite lower response rates, internet surveys yield similar statistics regarding health behaviors compared to mail and phone surveys [38]. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the data prohibits the establishment of causality, as temporality, frequency and dose/response issues cannot be assessed. Moreover, the overall goal of the survey was not to fully assess ma- rijuana use; thus, it lacked comprehensive assessments of marijuana use history, attitudes, beliefs, etc. Finally, data are derived from self-report and may be subject to bias. 4.2. Conclusions This study documents lower reported use of marijuana among two-year college students as well as unique per- sonality factors related to marijuana use among college students, specifically lower agreeableness and conscien- tiousness and greater openness to new experiences. This study suggests that these personality characteristics may assist researchers and practitioners in identifying those at risk for marijuana use and develop targeted interventions to address marijuana use among young adults. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (1K07CA139114-01A1; PI: Berg) and the Georgia Cancer Coalition (PI: Berg). We would like to thank our collaborators across the state of Georgia in developing and administering this survey. REFERENCES [1] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Admini- stration (2009) Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Ap- plied Studies, Rockville. [2] Johnston, L. (2009) Monitoring the Future national sur- vey results on drug use, 1975-2009, Volume I: Secon- dary school students. National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda. [3] Caldeira, K.M., Arria, A.M., O’Grady, K.E., Vincent, K.B. and Wish, E.D. (2008) The occurrence of cannabis use disorders and other cannabis-related problems among first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 397- 411. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.001 [4] Nocon, A., Wittchen, H.U., Pfister, H., Zimmermann, P. and Lieb, R. (2006) Dependence symptoms in young ca- nnabis users? A prospective epidemiological study. Jour- nal of Psychiatry Research, 40, 394-403. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.011 [5] National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2001). Traffic Safety Facts 2001. Washington, DC. [6] Mittleman, M.A., Lewis, R.A., Maclure, M., Sherwood, J.B. and Muller, J.E. (2001) Triggering myocardial in- farction by marijuana. Circulation, 103, 2805-2809. [7] Polen, M.R., Sidney, S., Tekawa, I.S., Sadler, M. and Friedman, G.D. (1993) Health care use by frequent ma- rijuana smokers who do not smoke tobacco. Western Journal of Medicine, 158, 596-601. [8] Tashkin, D.P. (1990). Pulmonary complications of smok- ed substance abuse. Western Journal of Medicine, 152, 525-530. [9] Zhang, Z.F., Morgenstern, H., Spitz, M.R., Tashkin, D.P., Yu, G.P., Marshall, J.R., et al. (1999) Marijuana use and increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head  C. J. Berg et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 (2011) 101-108 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/ 107 and neck. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Pre- vention, 8, 1071-1078. [10] Aryana, A. and Williams, M.A. (2007) Marijuana as a trigger of cardiovascular events: Speculation or scientific certainty? International Journal of Cardiology, 118, 141- 144. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.001 [11] Hashibe, M., Straif, K., Tashkin, D.P., Morgenstern, H., Greenland, S. and Zhang, Z.F. (2005) Epidemiologic re- view of marijuana use and cancer risk. Alcohol, 35, 265- 275. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.008 [12] Pope, H.G. Jr. and Yurgelun-Todd, D. (1996) The resi- dual cognitive effects of heavy marijuana use in college students. Journal of the American Medical Association, 275, 521-527. doi:10.1001/jama.275.7.521 [13] Brook, J.S., Zhang, C. and Brook, D.W. (2011) Devel- opmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: Personal predictors. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 165, 55-60. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.248 [14] Brook, J.S., Kessler, R.C. and Cohen, P. (1999) The on- set of marijuana use from preadolescence and early ado- lescence to young adulthood. Developmental Psychopa- thology, 11, 901-914. doi:10.1017/S0954579499002370 [15] Lynskey, M. and Hall, W. (2000) The effects of adoles- cent cannabis use on educational attainment: A review. Addiction, 95, 1621-1630. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116213.x [16] Lehman, W.E. and Simpson, D.D. (1992) Employee sub- stance use and on-the-job behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 309-321. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.77.3.309 [17] Brook, J.S., Richter, L., Whiteman, M. and Cohen, P. (1999) Consequences of adolescent marijuana use: In- compatibility with the assumption of adult roles. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 125, 193- 207. [18] Tarter, R.E. (1988) Are there inherited behavioral traits that predispose to substance abuse? Journal of Consult- ing and Clinical Psychology, 56, 189-196. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.56.2.189 [19] Brook, J.S., Lee, J.Y., Brown, E.N., Finch, S.J. and Brook, D.W (2011). Developmental trajectories of mari- juana use from adolescence to adulthood: Personality and social role outcomes. Psychological Reports, 108, 339- 357. doi:10.2466/10.18.PR0.108.2.339-357 [20] Windle, M. and Wiesner, M. (2004) Trajectories of ma- rijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: pre- dictors and outcomes. Developmental Psychopathology, 16, 1007-1027. doi:10.1017/S0954579404040118 [21] Hyman, S.M. and Sinha, R. (2009) Stress-related factors in cannabis use and misuse: Implications for prevention and treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse and Treat- ment, 36, 400-413. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.005 [22] Degenhardt, L., Hall, W. and Lynskey, M. (2001) The relationship between cannabis use and other substance use in the general population. Drug and Alcohol De- pendence, 64, 319-327. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00130-2 [23] Lynskey, M.T., Heath, A.C., Bucholz, K.K., Slutske, W.S., Madden, P.A., Nelson, E.C., et al. (2003) Escala- tion of drug use in early-onset cannabis users vs co-twin controls. Journal of American Medical Association, 289, 427-433. doi:10.1001/jama.289.4.427 [24] Magid, V., Colder, C.R., Stroud, L.R. and Nichter, M. (2009) Negative affect, stress, and smoking in college students: Unique associations independent of alcohol and marijuana use. Addictive Behaviors, 34, 973-975. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.007 [25] American College Health Association (2008) American college health association: National college health assess- ment Spring 2007 reference group data report (Abridged). Journal of American College Health, 56, 469-479. doi:10.3200/JACH.56.5.469-480 [26] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1997) Youth risk behavior surveillance: National college health risk behavior survey—United States, 1995. MMWR Surveil- lance Summaries, 46, 1-54. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/0004985 9.htm. [27] American College Health Association. (2009). American college health association: National college health assess- ment Spring 2008 reference group data report (Abridged). Journal of American College Health, 57, 477-488. doi:10.3200/JACH.57.5.477-488 [28] Office of Applied Studies (2006) The NSDUH Report, Edicted by SAMHSA, Rockville. [29] Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L. and Williams, J.B. (2003) The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41, 1284-1292. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [30] Cohen, S. and Lichtenstein, E. (1990). Perceived stress, quitting smoking, and smoking relapse. Health Psychol- ogy, 9, 466-478. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.9.4.466 [31] Stephenson, M.T., Hoyle, R.H., Palmgreen, P. and Slater, M.D. (2003) Brief measures of sensation seeking for screening and large-scale surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 72, 279-286. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.08.003 [32] Hoyle, R.H., Stephenson, M.T., Palmgreen, P., Lorch, E.P. and Donohew, R.L. (2002) Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 401-414. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00032-0 [33] Gosling, S.D., Rentfrow, P.J. and Swann, W.B. (2003) A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504-528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1 [34] Ream, G.L., Benoit, E., Johnson, B.D. and Dunlap, E. (2008) Smoking tobacco along with marijuana increases symptoms of cannabis dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95, 199-208. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.011 [35] Moir, D., Rickert, W.S., Levasseur, G., Larose, Y., Ma- ertens, R., White, P., et al. (2008) A comparison of main- stream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions [Comparative Study]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 21, 494-502. doi:10.1021/tx700275p [36] Kaplowitz, M.D., Hadlock, T.D. and Levine, R. (2004) A comparison of web and mail survey response rates Public Opinion Quarterly, 68, 94-101. [37] Crawford, S., McCabe, S. and Kurotsuchi-Inkelas, K. (2008) Using the web to survey college students: Institu-  C. J. Berg et al. / Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 1 (2011) 101-108 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/Openly accessible at 108 tional characteristics that influence survey quality. Paper presented at the American Association for Public Opin- ion Association. [38] An, L.C., Hennrikus, D.J., Perry, C.L., Lein, E.B., Klatt, C., Farley, D.M., et al. (2007). Feasibility of Internet health screening to recruit college students to an online smoking cessation intervention. Nicotine & Tobacco Re- search, 9, S11-S18. doi:10.1080/14622200601083418

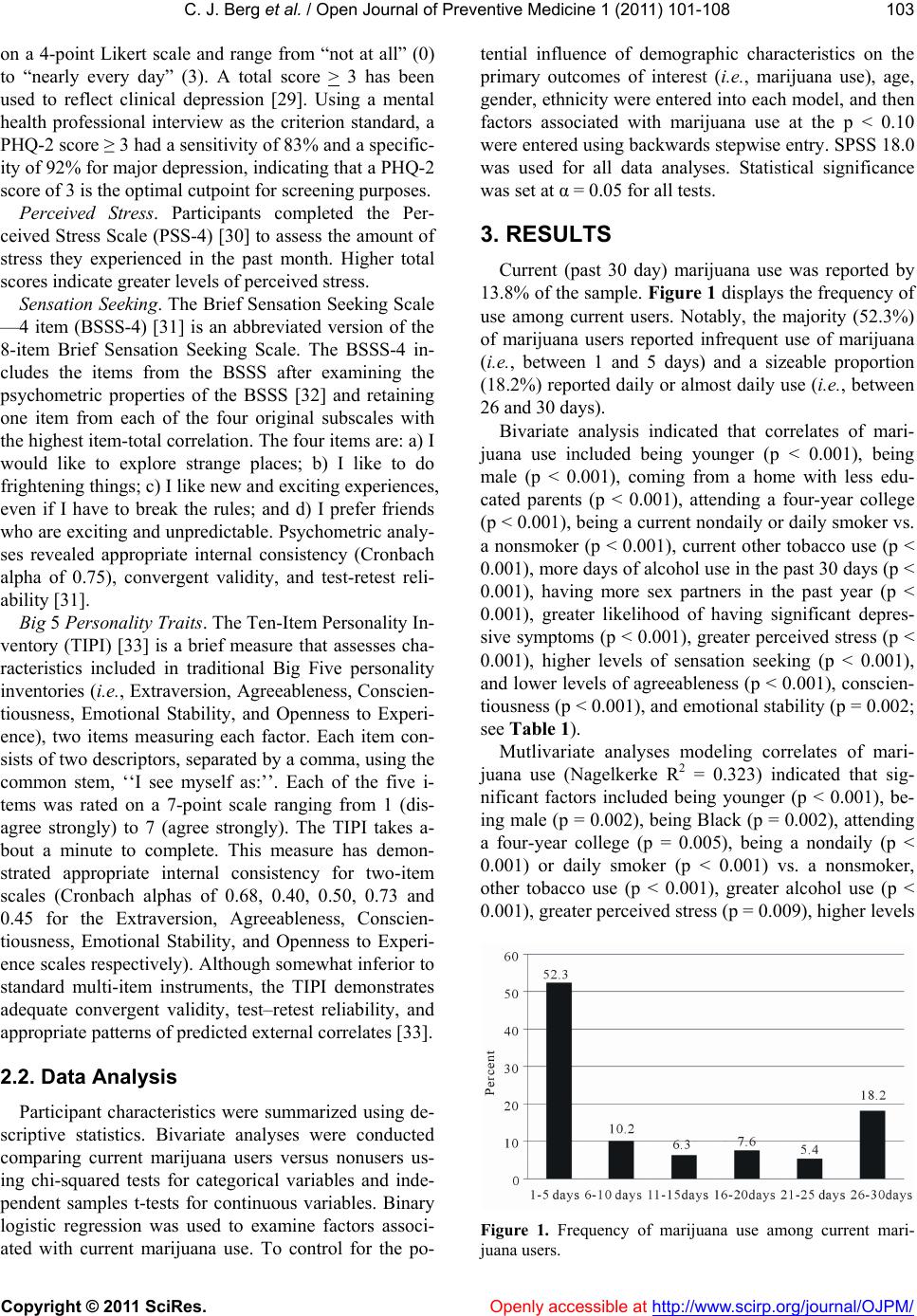

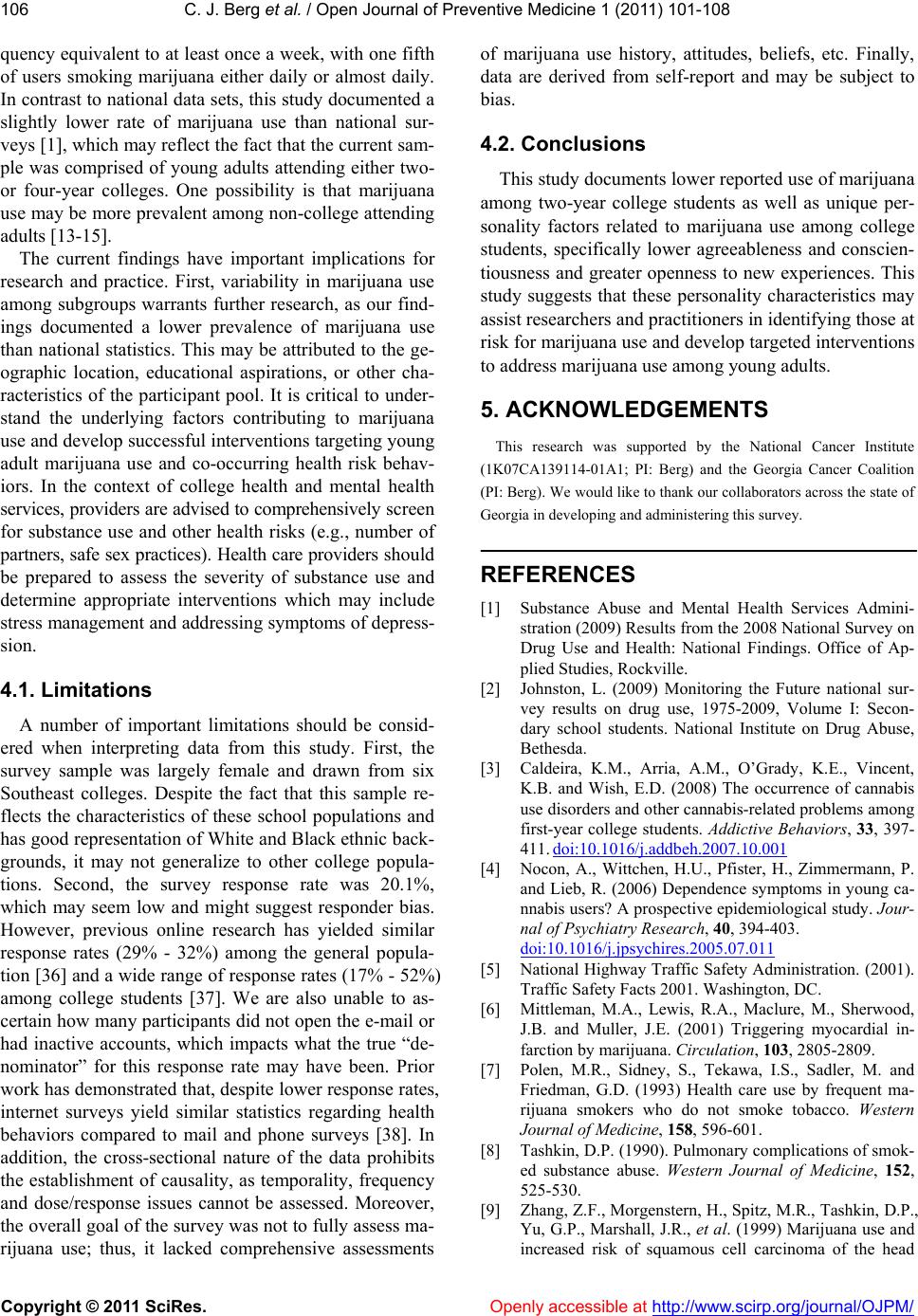

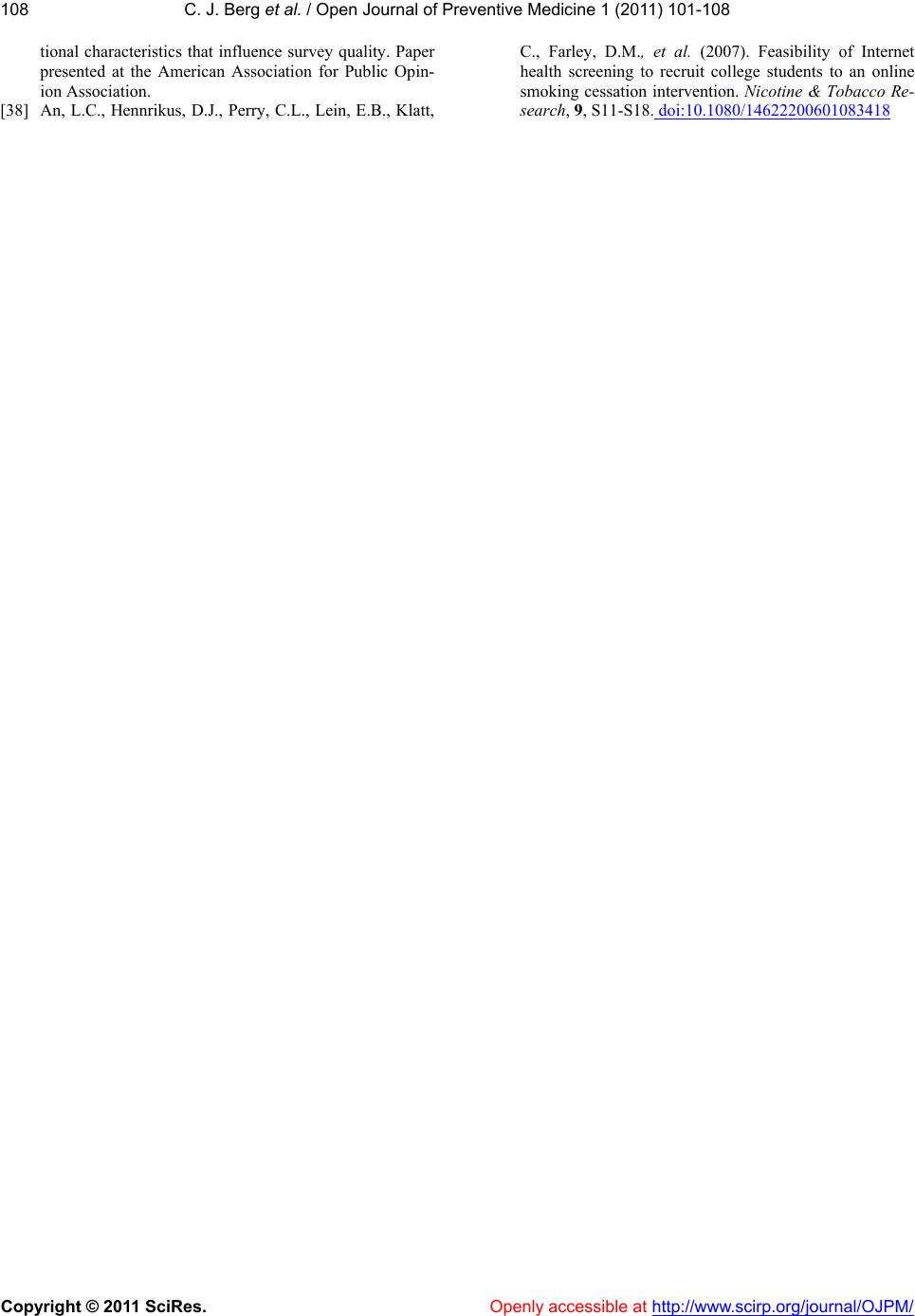

|