A. UTAKA

120

2

2

'''21 1'AMnufMfMf M

0.

1

Therefore, if

2

0'0210Anuf f

(and ), there exists a value

lim 0

MAM

*

that

satisfies (2).

2.3. Existence of Oscillations

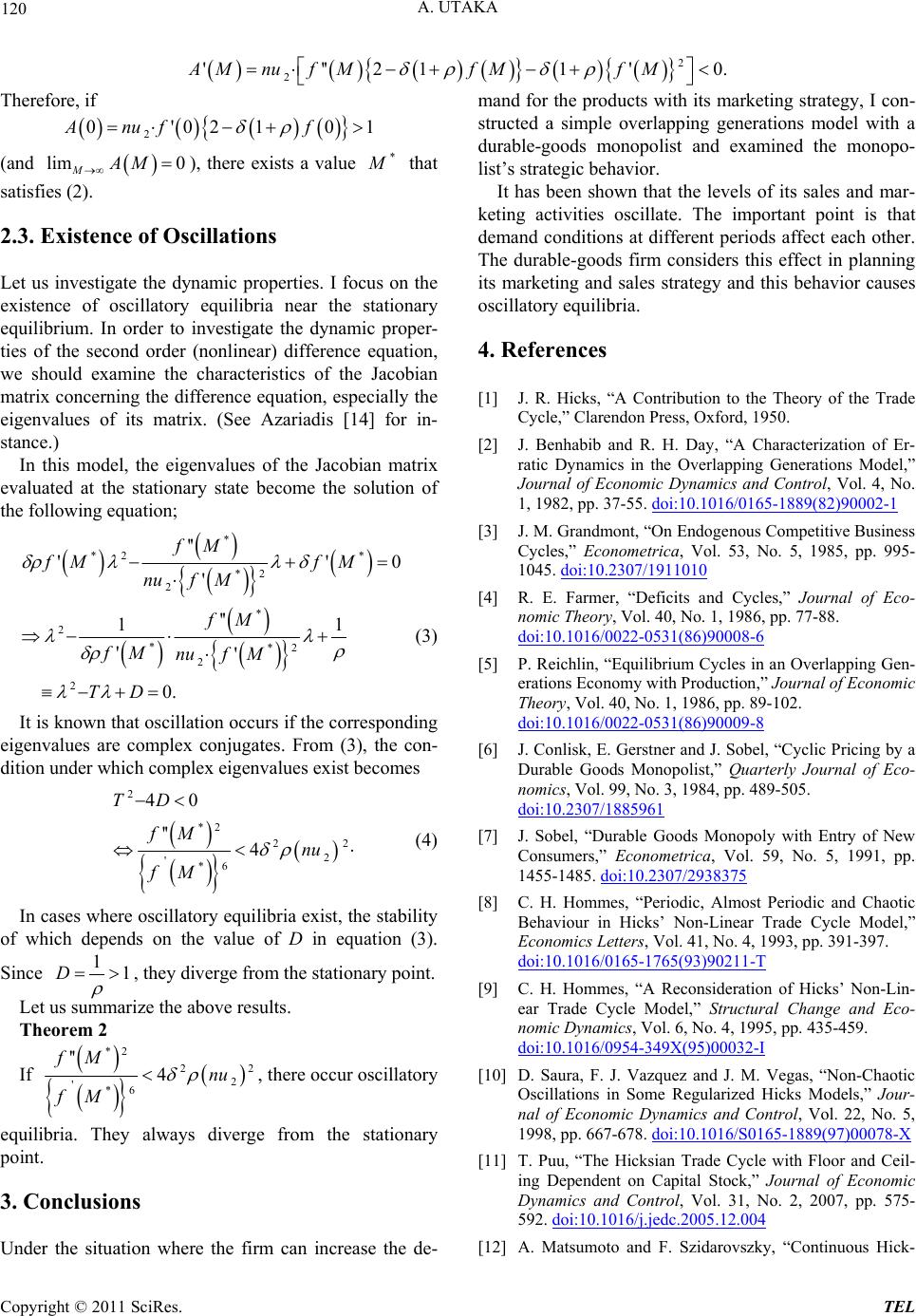

Let us investigate the dynamic properties. I focus on the

existence of oscillatory equilibria near the stationary

equilibrium. In order to investigate the dynamic proper-

ties of the second order (nonlinear) difference equation,

we should examine the characteristics of the Jacobian

matrix concerning the difference equation, especially the

eigenvalues of its matrix. (See Azariadis [14] for in-

stance.)

In this model, the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix

evaluated at the stationary state become the solution of

the following equation;

*

*2 *

*2

2

*

2

**2

2

2

''

'

'

''

1

''

0.

fM

fM fM

nuf M

fM

fM nuf M

TD

'

0

1

(3)

It is known that oscillation occurs if the corresponding

eigenvalues are complex conjugates. From (3), the con-

dition under which complex eigenvalues exist becomes

2

*2

2

2

'*6

40

'' 4

TD

fM nu

fM

2

(4)

In cases where oscillatory equilibria exist, the stability

of which depends on the value of D in equation (3).

Since 11D

, they diverge from the stationary point.

Let us summarize the above results.

Theorem 2

If

*2

2

2

'*6

'' 4

fM nu

fM

2

, there occur oscillatory

equilibria. They always diverge from the stationary

point.

3. Conclusions

Under the situation where the firm can increase the de-

mand for the products with its marketing strategy, I con-

structed a simple overlapping generations model with a

durable-goods monopolist and examined the monopo-

list’s strategic behavior.

It has been shown that the levels of its sales and mar-

keting activities oscillate. The important point is that

demand conditions at different periods affect each other.

The durable-goods firm considers this effect in planning

its marketing and sales strategy and this behavior causes

oscillatory equilibria.

4. References

[1] J. R. Hicks, “A Contribution to the Theory of the Trade

Cycle,” Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1950.

[2] J. Benhabib and R. H. Day, “A Characterization of Er-

ratic Dynamics in the Overlapping Generations Model,”

Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 4, No.

1, 1982, pp. 37-55. doi:10.1016/0165-1889(82)90002-1

[3] J. M. Grandmont, “On Endogenous Competitive Business

Cycles,” Econometrica, Vol. 53, No. 5, 1985, pp. 995-

1045. doi:10.2307/1911010

[4] R. E. Farmer, “Deficits and Cycles,” Journal of Eco-

nomic Theory, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1986, pp. 77-88.

doi:10.1016/0022-0531(86)90008-6

[5] P. Reichlin, “Equilibrium Cycles in an Overlapping Gen-

erations Economy with Production,” Journal of Economic

Theory, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1986, pp. 89-102.

doi:10.1016/0022-0531(86)90009-8

[6] J. Conlisk, E. Gerstner and J. Sobel, “Cyclic Pricing by a

Durable Goods Monopolist,” Quarterly Journal of Eco-

nomics, Vol. 99, No. 3, 1984, pp. 489-505.

doi:10.2307/1885961

[7] J. Sobel, “Durable Goods Monopoly with Entry of New

Consumers,” Econometrica, Vol. 59, No. 5, 1991, pp.

1455-1485. doi:10.2307/2938375

[8] C. H. Hommes, “Periodic, Almost Periodic and Chaotic

Behaviour in Hicks’ Non-Linear Trade Cycle Model,”

Economics Letters, Vol. 41, No. 4, 1993, pp. 391-397.

doi:10.1016/0165-1765(93)90211-T

[9] C. H. Hommes, “A Reconsideration of Hicks’ Non-Lin-

ear Trade Cycle Model,” Structural Change and Eco-

nomic Dynamics, Vol. 6, No. 4, 1995, pp. 435-459.

doi:10.1016/0954-349X(95)00032-I

[10] D. Saura, F. J. Vazquez and J. M. Vegas, “Non-Chaotic

Oscillations in Some Regularized Hicks Models,” Jour-

nal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 22, No. 5,

1998, pp. 667-678. doi:10.1016/S0165-1889(97)00078-X

[11] T. Puu, “The Hicksian Trade Cycle with Floor and Ceil-

ing Dependent on Capital Stock,” Journal of Economic

Dynamics and Control, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2007, pp. 575-

592. doi:10.1016/j.jedc.2005.12.004

[12] A. Matsumoto and F. Szidarovszky, “Continuous Hick-

Copyright © 2011 SciRes. TEL