Psychology 817 2011. Vol.2, No.8, 817-823 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. doi:10.4236/psych.2011.28125 The Role of Anxiety Sensitivity, Fear of Pain and Experiential Avoidance in Experimental Pain Ana Isabel Masedo Gutiérrez1, María Rosa Esteve Zarazaga1, Stefaan Van Damme2 1Department of Personality, Assessment and Psychological Treatment, Universit y of Mal aga, Málaga, Spain; 2Department of Psychology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. Email: masedo@uma.es Received June 1st, 2011; revised August 9th, 2011; accepted September 11th, 2011. The aim of this study was to investigate whether distraction is less effective when pain is perceived as threaten- ing. Forty-one female undergraduate participants were assigned to distraction and not distraction conditions that consisted in performing a distraction task and the threat value of the pain stimuli was manipulated using instruc- tions. AS, EA and FP were considered as covariates. Results indicated that distraction manipulation had a main effect on less pain intensity, more tolerance and less catastrophic thoughts. Interestingly, the covariate AS had a significant effect over tolerance and EA had an effect on distress and anxiety related to pain. These results sug- gest that AS and EA are distinct processes and that each could play a different role in the response to pain. Anxiety sensitivity involves behavioural avoidance, whereas EA is a rejection of the internal experience that contributes to an increase in emotional distress. Keywords: Distraction, Threat Value, Experiential Avoidance, Anxiety Sensitivity, Fear to Pain, Experimental Pain Introduction Distraction is a commonsense strategy used to control pain, and attention diversion training is an important element in most types of cognitive behavioural therapy. Nevertheless, the effec- tiveness of distraction in controlling pain is still a controversial matter and the results from clinical and experimental research are inconclusive (Ahles, Blanchard, & Leventhal, 1983; Cioffi, 1991; Goubert, Crombez, Eccleston, & Devulder, 2004; Hodes, Howland, Lightfoot, & Cleeland, 1990; Leventhal, 1992; McCaul & Malott, 1984; Morley, Shapiro, & Biggs, 2003; Roelofs, Peters, Van der Zijden, & Vlaeyen, 2004; Seminowicz & Davis, 2007; Turk, Meichenbaum & Genest, 1983; Ville- mure & Bushnell, 2002). Several studies have suggested that the effect of distraction or attention seems to be influenced by dispositional variables and the history of chronic pain (Fanurik, Zeltzer, Roberts, & Blount, 1993; Goubert et al., 2004; Heyne- man, Fremouw, Gano, Kirkland, & Heiden, 1990). Current cognitive-behavioural models of chronic pain (Le- them, Slade, Troup, & Bentley, 1983; Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000) suggest that fear of pain plays a crucial role in the transition from acute to chronic pain. Anxiety sensitivity (AS) has been proposed as an explanation for individual differences regarding pain-related fear (Norton & Asmundson, 2003) and pain-related avoidance behaviour, even after controlling for the effects of pain severity (Asmundson & Taylor, 1996; Plehn, Peterson, & Williams, 1998). AS is defined as a tendency to be specifically fearful of anxiety-related sensations such as arousal and to be alert to more possible threats (Keogh & Cochrane, 2002; Reiss & McNally, 1985) and, consequently, to avoid threatening stimuli (Lethem et al., 1983; Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000). The fear-avoidance model conceives of fear of pain as a specific phobia (Lethem et al., 1983; Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000), since fear responses will be specifically linked to potentially painful stimuli. In contrast, the so-called AS approach considers that fear of pain is a manifestation of a more fundamental fear: the fear of anxiety symptoms (Asmundson & Hadjistavpoulos, 2007; Norton & Asm undson, 2003). Several studies have postulated that the relationship between AS and fear of pain could be explained by attentional processes. Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally (1986) were the first to propose that high AS may be characterized by hypervigilant self-monitoring of internal physical sensations. Moreover, AS is related to cognitive biases toward physically threatening and pain-related stimuli (Keogh, Dillon, Georgiou, & Hunt, 2001; Stewart, Conrod, Gignac, & Pihl, 1998). Asmundson, Kuperos and Norton (1997) found that individuals with chronic pain and low AS were able to shift their attention away from stimuli related to pain, in contrast to the subjects with high AS. Keogh and Cochrane (2002) found that the tendency to negatively interpret ambiguous bodily sensations related to panic mediated the association between AS and emotional responses to cold pressor pain. Of note, AS was still related to affective pain scores when controlling for fear of pain . Experiential avoidance (EA) is another related construct which is defined as the general tendency to avoid internal events, to make excessively negative evaluations of unwanted private thoughts, feelings and sensations, to be unwilling to experience these private events and to make deliberate efforts to control or escape from them (Kashdan, Barrios, Forsyth and Steger, 2006). Several studies have indicated that individuals reporting higher levels of EA had lower pain endurance and tolerance and recovered more slowly from these particular types of aversive events (Marx & Sloan, 2002; Orsillo & Batten, 2005; Feldner, Hekmat, Zvolensky, Vowles, Secrist, & Leen-Feldner, 2006). Although AS and EA are related con- structs, they only share 9% of their variance (Hayes et al., 2004). However, it seems that the effect of distraction on pain de- pends on fear of pain and AS. Keogh and Mansoor (2001)  A. I. M. GUTIÉRREZ ET AL. 818 found that high AS individuals reported more pain in the avoidance condition than when they used focused strategies to cope with pain. Roelofs, Peters, Van der Zijden and Vlaeyen (2004) found that high fear of pain individuals obtained more benefit from focalization strategies than from distraction strate- gies. Apart from any individual differences that make individuals more prone to avoid internal events and sensations related to pain, the evaluative context of the noxious stimuli affects the pain it evokes, specifically any perceived tissue damage and its meaning (Moseley & Arntz, 2007). It has been argued that the selection of pain by the attentional system is strongly guided by the evolutionary adaptive urge to escape bodily threat (Crom- bez, Van Damme, & Eccleston, 2005). Standford, Kersh, Thorn, Rich and Ward (2002) found that the self-reported appraisal of threat was related to decreased tolerance to experimental pain. Van Damme et al. (2008) hypothesized that a high threat value of pain may interfere with the effects of distraction, and thus, that giving threatening instructions to the participants would reduce the effect of distraction on pain. They found that a high threat value of pain did not interfere with distraction, whereas performance worsened in the distraction task when threatening instructions were given. However, this study did not explore any vulnerability factors that might possibly influence the ef- fects of threat on the effectiveness of distraction. The present study investigates the interaction between some dispositional variables related to avoidance and the evaluative context to determine the influence of distraction on the experience of pain. To recapitulate, in the light of previous research, it was pos- tulated that the effectiveness of distraction to control pain would be less in a negative and threatening evaluative context and when the levels of FP, AS and EA were higher. Methods Participants Thirty-six female undergraduate psychology students (mean age = 20.21 years) voluntarily participated for course credits. All participants gave their informed consent and were free to terminate the experiment at any time. Exclusion criteria were the presence of a circulatory disorder, hypertension, diabetes, Raynaud’s disease, or a heart condition. No participants were excluded for any of these reasons. As indicated by Cohen (1988), the size of the experimental groups meant that the analysis had medium-high power (0.65) to detect medium-size effects (0.25) at a 0.05 significance level with one degree of freedom. Apparatus and Measures Cold Pressor Task. The cold pressor apparatus consisted of two 50 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm metal containers. One of the con- tainers was filled with water at room temperature (approxi- mately 21˚C). The other container was divided into two sec- tions by a wire screen. It was filled with water and the ice was placed on one side of the wire place, with the subjects hand and forearm immersed in the ice-free side. The water was main- tained at 6˚C - 7˚C via a circulating pump. Water temperature was measured using a digital thermometer immersed in the water and fixed to the container. A colder temperature was not considered appropriate for the purpose of this study, since a sufficiently large range of tolerance effects was required; how- ever, a limit of three hundred seconds was established to avoid any physical risk (Turk, 1984). Tolerance. Tolerance time is the length of time that the hand and forearm is under the cold water. The immersion time, measured in seconds, was recorded using a digital stopwatch. Distraction task. For the purposes of the study, the distraction task had to fulfil the following requirements: 1) there had to be no effort to suppress their thinking, sensations or emotions because paradoxical effects (Masedo & Esteve, 2007); 2) all the participants had to find the task easy to do. These requirements were fulfilled by designing a detection task that used LEDs. A panel was placed between the containers and the partici- pants. The panel contained two LEDs 5 cm above the holes where each hand was to be placed. The left-to-right distance between the LEDs was 31 cm. The participant’s head was maintained in a median position by a chin-rest device. When performing the distraction task the participants responded to the LEDs by means of two pedals, left and right, pressed by the dominant foot. The distraction task consisted of presenting one of the LEDs (left or right) for 200 ms and the participants had to press the corresponding left or right pedal as soon as possible. The duration of the task depended on the duration of immersion in the water. A maximum number of 135 trials were presented (corresponding to the limit of 300 seconds of immersion in the cold water) and time responses were recorded. The mean reac- tion time was 589 ms (SD = 216 ms). The inter-trial interval ranged between one and three seconds to avoid temporal pre- dictability and increase atten t ional engagement. Self-Report Instruments Anxiety Sensitivity was assessed using the Spanish version of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; Peterson, & Reiss, 1992; Sandin, Chorot, & McNally, 1996) which is fully equivalent to the original and whose construct and concurrent validity have been supported by cross-cultural evidence (Sandin, Chorot, & McNally, 1996). The Spanish version of the ASI has shown good psychometric properties for both reliability and validity (Sandín, Valiente, Chorot, & Santed, 2005). This is a 16-item questionnaire in which participants are asked to indicate the degree to which they fear the negative consequences of anxiety symptoms on a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 0 = very little to 4 = very much). The original ASI has very high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability (Peterson & Plehn, 1999; Peterson & Reiss, 1992). The total score was used as the global AS factor. Fear of pain was measured using the Spanish version of the Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FPQ-III; Camacho & Esteve, 2005; McNeil & Rainwater, 1998). It consists of 30 items that are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (ex- treme). It has three subscales related to three painful stimulus situations: fear related to severe pain (eg, breaking your arm); fear related to minor pain (e.g., having sand in your eye) and fear related to medical pain (e.g., receiving an injection in your mouth). The English version has suitable psychometric proper- ties (Osman, Breitenstein, Barrios, Gutierrez, & Koper, 2002) and the Spanish version has proven high internal consistency and a factorial structure similar to the former. It yielded a cor- related three-factor structure which corresponds to the three subscales of the instrument (Camacho & Esteve, 2005). The total fear of pain score was used. Experiential avoidance. The Acceptance and Action Ques- tionnaire (AAQ; Hayes et al., 2004; Barraca, 2004) consists in 9 items that are scored on a 7-point Likert scale. It assesses tendencies to make negative evaluations of private events (e.g.,  A. I. M. GUTIÉRREZ ET AL. 819 anxiety is bad), unwillingness to be in contact with private events, the need/desire to control or alter the form and fre- quency of private events and the inability to take action in the face of negatively evaluated private events. The Spanish ver- sion (Barraca, 2004) shows high internal consistency and valid- ity. Appraisal of the Experience of Pain Participants also completed items related to the pain experi- ence on 11-point rating scales adapted from Van Damme et al (2008). The items assessed the following: a) pain intensity (0 = no pain; 10 = the worst imaginable pain) using 4 items measur- ing pain during and after the cold pressor procedure; b) distress (0 = no distress; 10 = worst imaginable distress) using 3 items related to distress associated with pain; and c) general anxiety, using four items measuring how anxious and fearful they felt during the cold w a t er procedure. Catastrophic thinking about pain during the cold water pro- cedure was assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS; Sullivan et al., 1995) adapted to the experimental pain context. The original instrument is a 13-item scale that measures the level of catastrophic thinking about past pain episodes. Items more appropriate for the experimental pain situation were se- lected and translated into a 8-item scale where participants were asked to reflect on the experimental painful experience and to indicate the degree to which they experienced these thoughts or feelings during the pain task (e.g., Helplessness “I felt I couldn’t stand it anymore”, rumination “I was thinking all the time about when the pain was going to be over” and magnifica- tion “I was thinking the pain was horrible and was overwhelm- ing me”). The internal consistency of the total scale was high and the total score was used. Procedure First, the participants completed the ASI, AAQ and FPQ in class several days before the experimental session and were then scheduled for the experimental studies. When the partici- pants arrived the experimenter were told that the aim of the study was to examine pain perception by use of a cold pressor test. Exclusion criteria were checked and the participants signed an informed consent document. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions based on the manipulation of attention (distraction versus no distraction task) and threat (threatening information versus neutral information). Threat was manipulated by means of verbal instructions. Par- ticipants assigned to the threat condition received instructions about the cold pressor task adapted from previous studies (Jackson et al., 2005; Van Damme et al., 2008). They were told that “exposure to cold water can lead to freezing in the long term and that this may be associated with pain, tingling and numbness in the immersed hand”. In the neutral condition par- ticipants were told that “exposure to cold water is harmless, but it can be associated with some discomfort or pain, which is absolutely normal and has no further consequences”. Attention was manipulated by means of the distraction task. Only the participants in the distraction condition performed the task, but no information about the purpose of this task was given. They were asked to respond to visual targets as quickly as possible by pressing a foot pedal. They were instructed to immerse their non-dominant hand in the basin filled with room-temperature water to standardize its temperature for later immersion in cold water, and to keep their hand there for as long as possible. However, it was emphasized that they could withdraw their hand at any time during the cold water proce- dure. The participants in the distraction condition were in- structed to do the task at the same time as they had their hand in the cold water, whereas the participants in the non-distraction condition had to undergo the cold pressor condition but without performing any task. Tolerance time was measured using a stopwatch. When par- ticipants withdrew their hand from the container they were given a towel to dry themselves and then completed the rating scales and the adapted PCS. Results To assess the effect of distraction and threat manipulations, ANCOVAs were performed to determine whether the groups differed in relation to the pain experience (tolerance, reported pain and distress, general anxiety and catastrophizing ratings) after controlling for the influence of AS, EA and FP. Table 1 shows the means of the dependent variables as a function of conditions. The analyses showed a significant main effect for the distrac- tion manipulation. The distraction group showed more toler- ance (F(1) = 10,08, p = .004), reported less pain (F(1) = 5,54, p = .026) and had fewer catastrophic thoughts (F(1) = 11,34, p = .002) compared to the group that did not perform any task. The threat group was compared to the neutral group. No sig- nificant group differences were found regarding catastrophic thoughts (F(1) = .074, p= .787), pain reports (F(1) = .018, p = 895) and tolerance (F(1) = .019, p = .890). The threat group showed more general anxiety (F(1) = 4,88, p = .035) and more distress (F(1) = 2,89, p = .09), but distress rating differences showed a tendency to be significant. The interaction between the distraction and threat manipulation factors did not reach significance for any of the dependent variables (all F(s) < 1.65, Sig.(s) > 0.30). The covariates had significant effects on the experience of pain. AS had a significant influence on tolerance (F(1) = 6,81, p = .014), EA had a effect on distress (F(1) = 5,17, p = .031) and general anxiety (F(1) = 7,07, p = .013 ) and FP did not have any Table 1. Mean and standard deviations of dependent variables in function of distr action and threat. Total (N = 36) Threat (N = 16) Neutral (N = 20) Mean (SD) Distract (8) Non distract (8) Distract (11) Non distract (9) Tolerance Pain Catastrophizing Anxiety Distress 135,97 (109,47) 6.95 (1.31) 9.75 (5.72) 22.83 (11,68) 19,58 (8,34) 193,87 (118,51) 6.71 (1,30) 8,12 (5,43) 30,25 (11,12) 20,00 (7,01) 85.12 (89,16) 7.21 (1.12) 11.75 (5.20) 22,37 (7,20) 23.62 (9,60) 164,36 (111,75) 6.30 (1.55) 5.91 (3.83) 20,27 (12.08) 14,72 (9,37) 95,00 (92,93) 7,74 (.68) 14.11 (5.23) 19.77 (13,64) 21,55 (4,24)  A. I. M. GUTIÉRREZ ET AL. 820 effect on the dependent variables. Figure 1 summarizes the significant relationships found be- tween the dispositional variables (fear of pain, AS and EA), contextual variables (distraction and threat), and the dependent variables. Discussion The aim of this study was to investigate whether distraction is less effective when pain is perceived as threatening. Several notable results emerged from this study. The participants in the distraction condition reported less pain intensity, showed longer tolerance times to the cold water and reported fewer catastro- phic thoughts than participants who were not distracted. The effect of distraction did not interact with the threatening in- structions. These results are in line with a previous study (Van Damme et al., 2008) that failed to find any interaction between distraction and threat manipulations in a cold pressor procedure. They also obtained similar results: specifically, distraction ma- nipulation resulted in less pain once the cold pressor procedure was stopped and there tended to be less catastrophic thinking. The authors did not measure tolerance time, but they found that fewer participants withdrew from the cold pressor procedure when they were distracted. Both studies seem to show the bene- ficial effects of distraction (also see Hodes et al., 1990; James & Hardardottir, 2002; Johnson & Petrie, 1997; Miron et al., 1989; Petrovic et al., 2000). A number of reports show that pain is perceived as less intense when individuals are distracted from the pain (Bushnell & Duncan, 1999; Miron et al., 1989) despite the threat value of pain. Clinical applications would incorporate distraction only as a contextual key. In the present study, it had beneficial effects on a simple task in which the subjects had to respond to another sensory modality stimulus which competed with pain and that would not involve controlled and demanding processes (Koster, Rassin, Crombez, & Naring, 2003; Van Damme et al., 2007). Participants in Keogh and Mansoor’s (2001) study were instructed to ignore the sensations in the distraction condition and it was found that focused strategies were clearly superior. Moreover, these results are in line with previous studies which suggested that when distraction is ap- plied in the form of direct instructions or auto-instructions (“Think about this and try not to think about pain), paradoxical effects could be enhanced (Cioffi & Holloway, 1993; Masedo & Esteve, 2007). According to these results, the best form of distraction is to engage in daily activities. This result is consis- tent with therapeutic principles of acceptance, which suggest that avoidant behaviours often lead to disability and social iso- lation, and which aim at training patients to actively contact their experience while behaving effectively (Hayes et al., 1999). The threat conditi o n resulted in a more distressing experience of pain. The effect of threat on anxiety during the cold pressor did not reach significance; however, the scores were in the predicted direction. Jackson et al. (2005) found that threatening instructions led to the decreased use of distraction strategies, and Van Damme et al. (2007) found that threat led to less en- gagement in the distraction task. An important technical limita- tion of the present study is that engagement with the distraction task and reaction times were not measured. Nevertheless, threatening instructions elicited negative emotional reactions that could be expected to affect the general performance of a task and even the overall experience of pain. In line with previous studies, AS, as a dispositional variable which promotes avoidance, was associated with tolerance times (Asmundson & Norton, 1995; Asmundson & Taylor, 1996; Plehn, Peterson & Williams, 1998; Esteve & Camacho, 2008). In the context of experimental pain, tolerance could be consid- ered the behavioural measure of pain avoidance (Camacho & Esteve, 2007). Although AS was associated with shorter toler- ance time, no significant association was found between fear of pain and the experience of pain. These results support the AS approach (Asmundson & Hadjistavpoulos, 2007; Esteve & Camacho, 2008). Nevertheless, AS was not significantly asso- ciated with the subjective distress ratings, which contrasts with previous studies that only found differences between AS groups regarding subjective ratings of pain (Keogh & Birkby, 1999; Figure 1. Relationships between psicosocial antecedent variables, factors and dependent variables.  A. I. M. GUTIÉRREZ ET AL. 821 Schmidt & Cook, 1999; Keogh & Mansoor, 2001), but none in relation to tolerance. In contrast to the association between AS and behavioural avoidance, a significant association was found between EA and the subjective experience of pain which is consistent with pre- vious findings (Kashdan et al., 2006). Similarly, EA has been related to the ability to tolerate physical and psychological dis- tress which is a key determinant of emotional adaptation to aversive events (Feldner, Eifert, & Brown, 2001; Feldner et al., 2006). Thus, the potential importance of EA as a broad-based vulnerability to emotional distress has been supported by the present study (Feldner et al., 2006). Of further interest is the fact that the clinical implications of this result lend support to an approach based on acceptance of pain as the antithesis of EA (Orsillo, Roemer, & Barlow, 2003). Acceptance studies suggest that emotional avoidance processes may increase the intensity of pain experiences and acceptance strategies lead to better pain-related emotional adjustment (Hayes et al., 1999). These results suggest that AS and EA are distinct processes and that each could play a different role in the response to chronic pain. Anxiety sensitivity involves behavioural avoid- ance, whereas EA is a rejection of the internal experience that contributes to an increase in emotional distress. A disconnec- tion between subjective experience and behaviour could lead to this behaviour persisting despite increased distress. Future studies could test whether AS is more related to avoidance and EA to endurance coping as a maladaptative pain-related coping style to bear chronic pain (Hassenbring, Hallner, & Rusu, 2009). The findings of this study showed that vulnerability variables play a relevant role in the avoidance of pain and in the subjec- tive experience of pain. Studies with chronic pain population show also that certain clinical personality patterns were associ- ated with poor adjustment to chronic pain, concretely cognitive appraisal of harm predicted higher anxiety levels and greater perceived pain in chronic pain patients (Herrero, Ramírez- Maestre, & González, 2008). This has important implications since prevention programs could be optimized regarding effi- cacy if specific therapeutic approaches were designed to treat individuals with high scores in EA and AS. The present study has important limitations. The ability to generalize the results is limited because of the small sample size. Furthermore, this study was conducted with undergradu- ates. Caution should be exercised in generalizing these results to clinical populations until these effects have been examined more extensively. Like previous studies (Keogh & Mansoor, 2001; Roelof, Peters, Van der Zijden, & Vlaeyen, 2004), this study was limited to women since previous research has found that women often score higher on the ASI than men. Future research may be designed to further explore the relationship between AS and gender. Acknowledgements This research was supported by grants from the University of Málaga, Dirección General de Enseñanza Superior (BSO2002- 02939) and the Junta de Andalucía (HUM-566). References Ahles, T., Blanchard, E., & Leventhal, H. (1983). Cognitive control of pain: Attention to the sensory aspects of the cold pressor stimulus. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 7, 159-177. doi:10.1007/BF01190070 Asmundson G. J. G., & Taylor S. (1996). Is high fear of pain associ- ated with attentional biases for pain-related or general threat? A categorical reanalysis. Journal of Pain, 8, 11-18. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2006.05.008 Asmundson G. J. G., Kuperos, J. L., & Norton G. R. (1997). Do pa- tients with chronic pain selectively attend to pain-related information: Preliminary evidence for the mediating role of fear. Pain, 72, 27-32. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00010-9 Sandín, B, Valiente, R. M., Chorot, P., & Santed, M. A. B. (2004). Propiedades psicométricas del índice de sensibilidad a la ansiedad. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 4, 505-515. Bushnell, M. C., D uncan, G. H., Hofb auer, R. K., Ha, B., Ch en, J. I., & Carrier, B. (1999). Pain perception: Is there a role for primary soma- tosensory cortex? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 96, 7705-7709. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.14.7705 Camacho L., & Esteve M. R. (2008). Anxiety sensitivity, body vigi- lance and fear to pain. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 715- 727. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.012 Cioffi, D. (1991). Sensory awareness versus sensory impression: Affect and attention interact to produce somatic meaning. Cognition and Emotion, 5, 275-294. doi:10.1080/02699939108411041 Cioffi, D., & Holloway, J. (1993). Delayed costs of suppressed pain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 274-282. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.274 Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Crombez G., Eccleston C., Baeyens F., & Eelen P. (1998). When so- matic information threatens, catastrophic thinking about pain en- hances attentional interference. Pain, 75, 187-198. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00219-4 Crombez G., Van Damme S., & Eccleston C. (2005). Hypervigilance to pain: An experimental and clinical analysis. Pain, 116, 4-7. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.035 Eccleston C., & Crombez G. (1999). Pain demands attention: a cogni- tive biases and the experience of pain. European Journal of Pain, 4, 37-44. Esteve M. R., & Camacho L. (2008). Anxiety sensitivity, body vigi- lance and fear of pain. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 715- 727. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.012 Fanurik D., Zeltzer L. K., Roberts M. C., & Blount R. L. (1993). The relationship between children’s coping styles and psychological in- terventions for cold pre sso r pain. Pain, 52, 255-257. Feldner, M. T., & Hekmat, H. (2001) Predictions of pain behaviors in a cold pressor task. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 32, 191-202. doi:10.1016/S0005-7916(01)00034-9 Feldner, M. T., Hekmat, H., Zvolensky, M. J., Vowles, K. E., Secrist, Z., & Leen-Feldner, E. W. (2006). The role of experiential avoidance in acute pain tolerance: A laboratory test. Journal of Behavior Ther- apy and Experimental Psychiatry, 37, 146-158. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.03.002 Goubert L., Crombez G., Eccleston C., & Devulder J. (2004). Distrac- tion from chronic pain during a pain-inducing activity is associated with greater post-activity pain. Pain, 110, 220-227. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.034 Hayes, S., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Guilford. Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., Wilson, K. G., Bissett, R. T., Pistorello, J., Toarmino, D., Pol usny, M. A ., Dykstra, T. A., Batten, S. V., Berg an, J., Stewart, S. H., Zvolensky, M. J., Eifert, G. H., Bond, F. W., For- syth, J. P., Karekla, M., & McCurry, S. M. (2004). Measuring expe- riential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psy- chological Record, 54, 553-578. Hassenbring, M., Hallner, D., & Rusu, A. C. (2008). Fear-avoidance and endurance-related r esponses to pain: Development and validation of the Avoidance-Endurance Questionnaire (AEQ). European Jour- nal of Pain, in press. Heyneman N. E., Fremouw W. J., Gano D., Kirkland F., & Heiden L. (1990). Individual differences in the effectiveness of different coping strategies for pain. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 63-77. doi:10.1007/BF01173525 Herrero, A., Ramírez-Maestre, C., & González, V. (2008). Personality,  A. I. M. GUTIÉRREZ ET AL. 822 cognitive appraisal and adjustment in chronic pain patients. The Spanish Journal of Psy chology, 11, 531-542. Hodes R. L., Howland E. W., Lightfoot N., & Cleeland C. (1990). The effects of distraction on responses to cold pressor pain. Pain, 41, 109-114. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(90)91115-Y Jackson T., Pope L., Nagasaka T., Fritch A., Lezzi T., & Chen H. (2005). The impact of threatening information about pain on coping and tolerance. British Journal of Health Psych ia tr y , 10, 441-451. doi:10.1348/135910705X27587 James J. E., & Hardardottir D. (2002). Influence of attention focus on pain. British Journal of Health Psychiatry, 7, 149-162. doi:10.1348/135910702169411 Kashdan, T. B., Barrios, V., Forsyth, J. P., & Steger, M. F. (2006). Experimential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behav- ior Research and Therapy, 9, 13011320. Keogh E, & Birkby J. (1999). The effect of anxiety and gender on the experience of pain. Cognitive Emotion, 13, 813-329. doi:10.1080/026999399379096 Keogh E., Dillon C., Georgiou G., & Hunt C. (2001). Selective atten- tion biases for physical-threat anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorder, 15, 299-315. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(01)00065-2 Keogh E., & Mansoor L. (2001). Investigating the effects of anxiety sensitivity and coping on the perception of cold pressor pain in healthy women. European Journal of Pain, 5, 11-25. doi:10.1053/eujp.2000.0210 Keogh E., & Cochrane M. (2002). Anxiety sensitivity, cognitive biases and the experience of pain. Journal of Pain, 3, 320-329. doi:10.1054/jpai.2002.125182 Lethem J., Slade P. D., Troup J. D. G., & Bentley G. (1983). Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perceptions. Behavior Research and Therapy, 21, 401-408. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(83)90009-8 Keogh E., Thompson T., & Hannent I. (2003). Selective attentional bias, conscious awareness and fear of pain. Pain, 104, 85-91. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00468-2 Koster, E. H., Rassin, E., Crombez, G., & Näring, W. B. (2003). The paradoxical effects of suppressing anxious thoughts during imminent threat. Behavior Research and Therapy, 41, 113-1120. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00144-X Leventhal, H. I. (1992). Know distraction works even though it doesn’t. Health Psychology, 11, 20 8-209. doi:10.1037/h0090350 Lillienfeld S. O. (1997). The relation of anxiety sensitivity to higher and lower order personality dimensions: Implications for the aetiol- ogy of panic attacks. Jour na l of Abnormal Psychiatry, 106, 539-544. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.106.4.539 Masedo A. I., & Esteve M. R. (2007). Effects of suppression, accep- tance and spontaneous coping on pain tolerance, pain intensity and distress. Behav ior Re searc h and Ther apy, 45, 199-209. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.02.006 Marx, B. P., & Sloan, D. M. (2002). The role of emotion in the psy- chological functioning of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Behavior Therapy, 33, 563-577 . doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80017-X McCaul K. D., Monson N., & Maki R. H. (1992). Does distraction reduce pain-produced distress among college students? Health Psy- chology, 11, 210-217. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.11.4.210 McNeil D. W., & Rainwater A. J. (1998). Development of the fear of pain questionnaire-III. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25, 389-410. doi:10.1023/A:1018782831217 Miron D., Duncan G. B., & Bushnell M. C. (1989). Effects of attention on the intensity and umpleasantness of thermal pain. Pain, 39, 345- 352. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(89)90048-1 Moseley G. L., & Arntz A. (2007). The context of a noxious stimulus affects the pain it evokes. Pain, 133, 64-71. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.002 Morley, S., Shapiro, D. A., & Biggs, J. (2003). Developing a treatment manual for attention management in chronic pain. Cognitive and Behavior Therapy, 32, 1-12. Norton P. J., & Asmundson G. J. G. (2003). Amending the fear-avoid- ance model of chronic pain: What is the role of physiological arousal? Behavior Therapy, 34, 17-30. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80019-9 Peterson R. A., & Reiss S. (1992). Anxiety sensitivity index manual (2nd ed.). Worthi ngt on, OH: International Diagnostic Syste ms. Peterson R. A., & Plehn K. (1999). Measuring anxiety sensitivity. In: S. Taylor (ed.), Anxiety sensitivity: Theory, research and treatment of the fear of anxiety (pp. 61-81), London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associ- ates. Petrovic P., Peterson K. M., Ghatan P. H., Stone E. S., & Ingvar M. (2000). Pain related cerebral activation is altered by a distracting cognitive task. Pain, 85, 19-30. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00232-8 Plehn K., Peterson R. A., & Williams D. A. (1998). Anxiety sensitivity: It relationship to funtional status in patients with chronic pain. Jour- nal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 8, 213-222. doi:10.1023/A:1021330607652 Osman A., Breitenstein J. L. L., Barrios F. X., Gutiérrez P. M., & Ko- per B. A. (2002). The fear of pain questionnaire-III: Further reliabil- ity and validity with nonclinical samples. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25, 155-173. doi:10.1023/A:1014884704974 Orsillo, S. M., Roemer, L., & Barlo w, D. H. (2003). Integrating accep- tance and mindfullness into existing cognitive-behavioral treatment for GAD: A case study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10, 222- 230. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80034-2 Reiss S., & McNally R. J. (1985). Expectancy model of fear. In S. Reiss and R. R. Bootzin (Eds.), Theoretical issues in behaviour ther- apy (pp. 107-121). San Diego: Academic Press. Reiss S., Peterson R. A., Gursky M., & McNally R. J. (1986). Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Be- havior Research and Therapy, 24, 1-8. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9 Roelofs J., Peters M. L., Van der Zijden M., & Vlaeyen J. W. S. (2004). Does fear of pain moderate the effects of sensory focusing and dis- traction on cold pressor pain in pain free individuals? The Journal of Pain, 5, 250-256. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2004.04.001 Sandin B., Chorot P., & McNally R. J. (1996). Validation of Spanish version of the anxiety sensitivity index in a clinical sample. Behavior Research and Therapy, 34, 283-290. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(95)00074-7 Schmidt N. B., Lerew D. R., & Jackson R. J. (1997). The role of anxi- ety sensitivity in the pathogenesis of panic: Prospective evaluation of spontaneous panic attacks during acute stress. Journal of Abnormal Psycholy, 106, 355-364. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.106.3.355 Schmidt N. B., & Cook B. H. (1999). Effects of anxiety sensitivity on anxiety and pain during a cold pressor challenge in patients with panic disorder. Behavior R esearch and Therapy, 37, 313-323. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00139-9 Seminowicz D. A., & Davis K. D. (2007). A re-examination of pain-cognition interactions: Implications for neuroimaging. Pain, 130, 8-13. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.036 Standford, S., Kersh, B., Thorn, B., Rich, M. A., & Ward, L. C. (2002). Psychosocial mediators of sex differences in pain responsivity. Journal of Pain, 3, 58-64. doi:10.1054/jpai.2002.xb30066 Stewart S. H., Conrod P. J., Gignac M., & Pihl R. O. (1998). Selective processing biases in anxiety-sensitive men and women. Cognition and Emotion, 12, 105-133. doi:10.1080/026999398379808 Sullivan M. J. L., Bishop S. R., & Pivik J. (1995). The pain catastro- phizing scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assesment, 7, 524-532. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524 Sullivan M. J. L., & Neish N. (1999). The effects of disclosure on pain during dental hygiene treatment: The moderating role of catastro- phizing. Pain, 79, 155-163. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00163-8 Sullivan M. J. L., Thorn B., Haythornthwaite J., Keefe F. J., Martin M., Bradley L. et al. (2001). Theoretical perspectives on the relation be- tween catastrophizing and pain. Clinical Journal of Pain, 17, 103- 115. doi:10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008 Taylor S., Koch W. J., & McNally R. J. (1992). How does anxiety vary across the anxiety disorders? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 6, 249- 259. doi:10.1016/0887-6185(92)90037-8 Turk D. C., Meichembaum D., & Genest M. (1984). Pain and behav- ioral medicine: A cognitive behavioural perspective. New York: Gu- ildford Press. Vallis T. M. (1984). A complete component analysis of stress inocula- tion for pain tolerance. Cognitive Therapy and Resear ch, 8, 313-329. doi:10.1007/BF01173001 Vancleef L. M. G., & Peters M. L. (2006). Pain catastrophizing, but not injury/illness sensitivity or anxiety sensitivity, enhances attentional  A. I. M. GUTIÉRREZ ET AL. 823 interference by pain. The Journal of Pain, 7, 23-30. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2005.04.003 Van Damme S., Crombez G., Bijttebier P., Goubert L., & Van Houden- hove B. (2002). A confirmatory factor analysis of the Pain Catastro- phizing Scale: Invariant factor structure across clinical and non- clinical populations . Pain, 96, 319-324. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00463-8 Van Damme S., Crombez G., Van Nieuwenborgh-De Wever K., & Goubert L. (2008). Is distraction less effective when pain is threat- ening. An experimental investigation with the cold pressor task. European Journal of Pain, 12, 66-67. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.03.001 Van Damme S., Legrain V., Vogt J., & Crombez G. Keeping pain in mind: A motivational account of attention to pain. Neuroscience Biobehaviorist Review, in press. Villemure C., & Bushnel M. C. (2002). Cognitive modulation of pain: How do attention and emotion influence pain processing? Pain, 95, 195-199. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00007-6 Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Linton, S. J. (2002). Fear-avoidance and its con- sequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain, 85, 317-332. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0 Zvolensky M. J., Goodie J. L., McNeil D. W., Sperry J. A., & Sorrell J. T. (2001). Anxiety sensitivity in the prediction of pain-related fear and anxiety in a heterogeneus chronic pain population. Behavior Re- search and Therapy, 39, 6 83-696. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00049-8

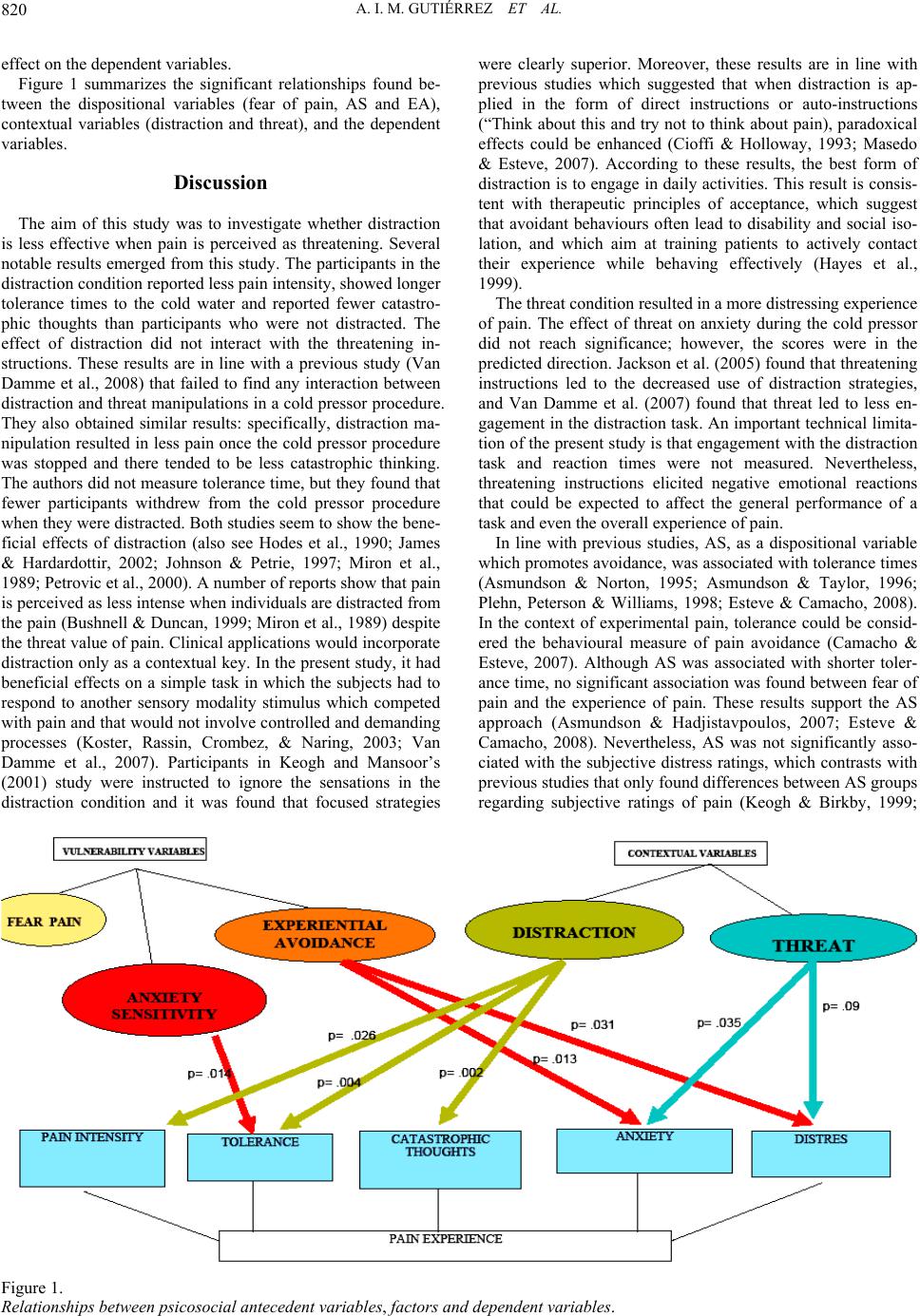

|