Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

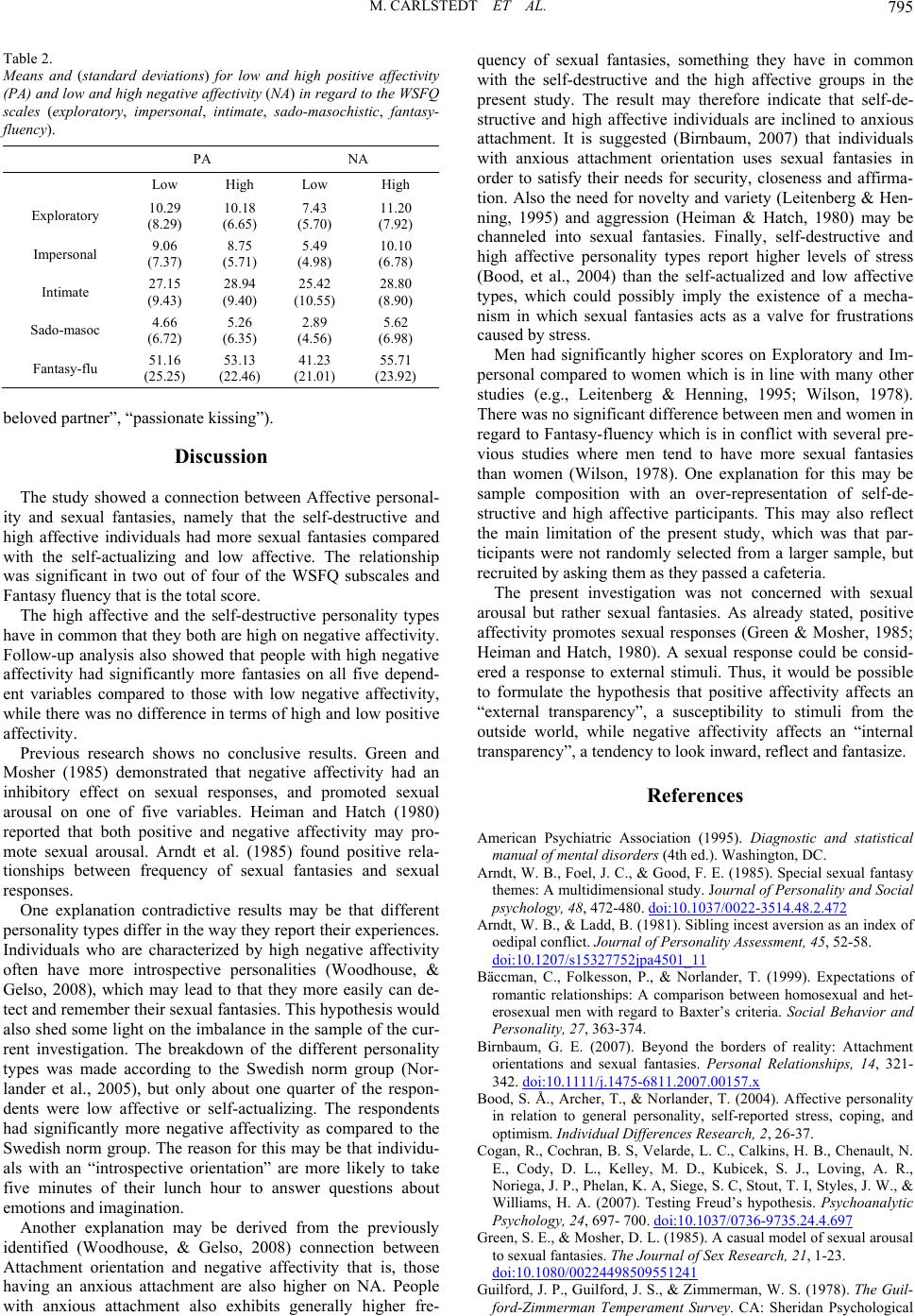

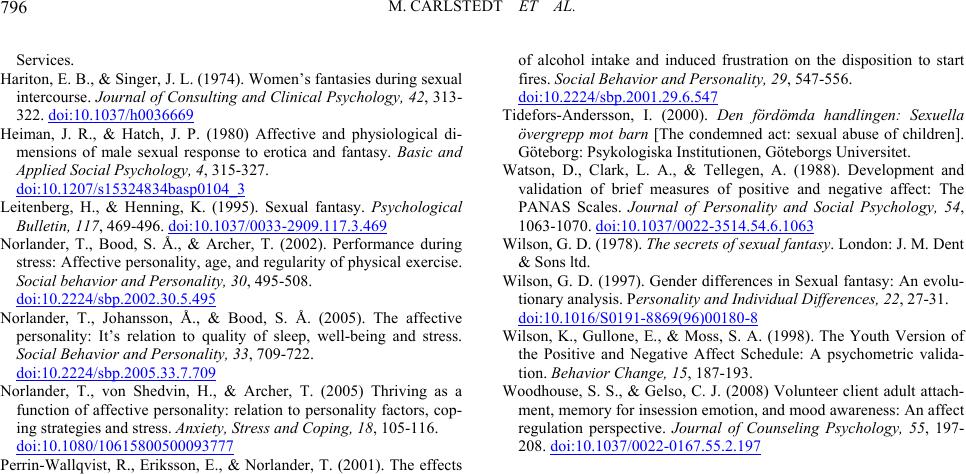

Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.8, 792-796 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.28121 The Affective Personality and Its Relation to Sexual Fantasies in Regard to the Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire Mathias Carlstedt, Sven A. Bood, Torsten Norlander Department of Psychology, Karlstad University, Karlstad, Sweden. Email: torsten.norlander@kau.se Received April 29th, 2011; revised August 29th, 2011; accepted October 6th, 2011. The present study investigated associations between affective personality types, sex and sexual fantasies. Par- ticipants were 209 students, 75 men and 134 women who completed the Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionaire (Wil- son 1978) and the Positive and Negative Affect Scales (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Results showed that self-destructive and high affective personality types had more sexual fantasies compared to self-actualizing and low affective types. Men had significantly higher scores on exploratory and impersonal sexual fantasies com- pared to women. It was suggested that positive affectivity is associated with “external transparency” that is, a susceptibility to stimuli from the outside world, while negative affectivity is associated with “internal transpar- ency” that is a tendency to look inward, reflect and fantasize. Keywords: Sexuality, Fantasy, PANAS, Affective Personality Introduction A sexual fantasy may be defined as an erotic yearning or constellation of mental images that evoke sexual arousal (Segen’s Medical Dictionary, 2011). In sexual fantasies a per- son may experience whatever he or she wants no matter how dangerous, illegal, socially unacceptable or impossible it would be to experience that in reality. Results indicate (Leitenberg, & Henning, 1995; Wilson, 1997) that sexual fantasies provide a better picture of a person’s sexuality compared to actual sexual behavior since the latter must take into account social conven- tions. Sexual fantasies may be memories of experiences, or plans for future activities, or experiences that seldom happen in real life. They may be things one wants to experience as well as things one never desires to transform into reality. They may be sudden daydreams in a moment of boredom or conscious strategies for enhancing the experience of masturbation or sex- ual intercourse. In any case, sexual fantasies are something most people occasionally experience (Leitenberg, & Henning, 1995; Wilson, 1978). Frequency of sexual fantasies has been shown to correlate positively with the frequency of orgasms, ability to become sexually aroused, and sexual satisfaction (Arndt, Foel, & Good, 1985; Cogan, Cochran, Velarde, Calkins, Chenault, Cody, Kel- ley, Kubicek, Loving, Noriega, Phelan, Siege, Stout, Styles, & Williams, 2007) and it is now considered pathological not to have sexual fantasies (American Psychiatric Association, 1995). However, it is not clear whether or not frequent sexual fantasies contribute to a satisfying sex life, or are the result of good sex life (Cogan et al., 2007). There are a number of factors that may be related to the unique profile of sexual fantasies of an individual. Biological sex is probably the most investigated factor associated with sexual fantasies. Men report more sexual fantasies than women (Leitenberg, & Henning, 1995; Wilson 1978; Wilson 1997). Different themes occur with different frequency between men and women. Men fantasize about a wider variety of imaginary partners, and more about having multiple partners simultane- ously. Men more often fantasize about having sex with anony- mous strangers. Women fantasize about having sex with fa- mous people, and with other women. Men are generally more active in their fantasies, while women are more passive. Men fantasize about performing sexual acts while women are more inclined to have fantasies being the subject of sexual acts. Men also have more dominance fantasies (fantasies that dominate someone else) while women have more submission fantasies (fantasies of being dominated) (Leitenberg, & Henning, 1995). Finally, men more often fantasize about rape: both to rape and being raped (Wilson 1978). There have also been studies showing the link between sex- ual fantasies and personality. Hariton and Singer (1974) found correlations between women’s personality and types of sexual fantasies. For example, women with great variation in their fantasies tended to be more impulsive, independent, and non- conformist, while women with sado-masochistic themes were more controlled, serious, and reclusive. Arndt et al. (1985) examined various sexual fantasies in men and women in regard to the Guilford-Zimmerman Temperament Survey (Guilford, Guilford & Zimmerman, 1978), and The Sibling Incest Aver- sion Scale (Arndt & Ladd, 1981). Guilford-Zimmerman Tem- perament Survey measures personality based on ten different dimensions, such as self-control, kindness and emotional stabil- ity. The authors found links between different themes in sexual fantasies on both instruments. Green and Mosher (1985) investigated responses to sexual stimuli in relation to five affective variables: fear, guilt, disgust, joy, and interest. Their hypothesis was that positive emotions (joy and interest) promote sexual arousal, while negative emo- tions (fear, guilt, disgust), inhibited sexual arousal. They found only one significant effect for positive affectivity, which, how- ever, did promote sexual arousal. There were no significant effects for negative affectivity. Another study (Heiman & Hatch, 1980) examining influences from various different emo- tions on men's sexual responses, reported that both positive and negative affectivity may promote sexual arousal. Birnbaum (2007) investigated two strategies to deal with problems that involve forging secure emotional ties to other people: anxious attachment and avoidant attachment. A person  M. CARLSTEDT ET AL. 793 with avoiding attachment avoids close relationships with other people (to avoid confronting the uncertainty for proximity), while a person with an anxious attachment on the contrary, frantically cultivate their close relationships and have an insa- tiable need for closeness and tenderness (to compensate for emotional insecurity). Birnbaum hypothesized that people with anxious attachment also have more sexual fantasies. Further- more, it was found that men with anxious attachment had more romantic fantasies and focus on satisfying their partner, while women with anxious attachment had more impersonal and un- fettered imagination, so it was concluded that people with anx- ious attachment seem to have less sexual fantasies. Individuals with avoidance attachment have fewer romantic fantasies. Woodhouse and Gelso (2008) found that people with anxious attachment also experience a high negative affect, while those with avoidance attachment behavior deny and repress negative feelings. A frequently used scale assessing affect is the PANAS (Posi- tive Affect and Negative Affect Scales) (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Wilson, Gullone, and Moss (1998) demon- strated that there usually is no significant correlation between positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). Therefore, Nor- lander, Bood, and Archer (2002) concluded that it was possible, at the level of the individual, to have different combinations of high or low PA and NA values. Norlander, et al. (2002) com- bined the scales into a model with four affective personality types: Self-actualizing with a high PA and low NA; High affec- tive with a high PA and high NA; Low affective with a low PA and low NA, and Self-destructive with a low PA and high NA. Since then, a growing research has been conducted on affec- tive personality. Results indicate, among other things, that indi- viduals with a Self-actualizing affective personality experience the least stress and those with a Self-destructive personality the most stress, whereas the Low affective personality type experi- ences the second lowest and the High affective type the second highest level of stress of the four affective personality types (Bood, Archer, & Norlander, 2004). Concerning affective per- sonality and posttraumatic experiences, results indicate (Nor- lander, von Schedvin, & Archer, 2005) a greater ability to re- cover by the High Affective personality type compared with the Self-destructive and Low affective types. The Self-actualizing showed an intermediary response. With regard to sleep quality (Norlander, Johansson, & Bood, 2005) individuals who display high positive affect, optimism and a high level of energy achieve a better sleep quality, and that this phenomenon may be true even when these individuals simultaneously experience high levels of stress and negative affectivity. The aim of the present study was to investigate possibly as- sociations between Affective personality types and sexual fan- tasies. To our knowledge there are presently no such studies available necessitating that the current study is exploratory in nature. Methods Participants The present study had 209 participants, 75 men and 134 women. Their mean age was 26.1 years (SD = 8.81, range = 19 to 87). Participants were grouped in terms of Affective person- ality (that is, Self-actualizing with a high PA and low NA; High affective with a high PA and high NA; Low affective with a low PA and low NA, and Self-destructive with a low PA and high NA). Statistics by ANOVA revealed no significant differ- ences in age either for Affective personality or Sex. Design The study had two independent variables, namely Affective personality (consisting of the four personality types: self-de- structive, low affective, high affective, self-actualizing) and Sex of participants (men, women). The four affective personality types were derived from the PANAS test (Watson, et al., 1988) by a method developed by Norlander, et al. (2002). There were 89 people in the Self-destructive group (38 men and 51 women), 27 in the Low affective group (12 men and 15 women), 67 of the High affective group (20 men and 46 women), and finally 26 people in the Self-actualizing group (4 men and 22 women). Dependent variables were various types of sexual fantasies as measured by the Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire (Wilson, 1978). Instruments Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scales. The PANAS- instrument (Watson, et al., 1988; Norlander et al., 2002) pro- vides information on the degree of positive and negative affec- tivity. It consists of ten adjectives for positive affectivity (PA), for example, “committed” “proud” and “active” and ten adjec- tives for negative affectivity (NA), such as “upset” “hostile” and “frightened”. The adjectives describe feelings and emo- tional states. For each word respondents are allowed to indicate, on a five-point scale, how often they had that feeling during the last week. The scores for the positive words are then summoned to a PA-value and likewise a NA-value is created. Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .75. Norlander, et al. (2002) improved on the PANAS instrument by deriving four different personality types. This was achieved by dividing the results on the PA-scale into two halves, one with high PA and one with low PA. The same procedure was used regarding the NA scale, yielding four different groups. In the current study the distribution was based on the Swedish norm group for the PANAS instrument (N = 1010). Cut-off points for low PA = 35 or less, for high PA = 36 or above, for low NA = 17 or less and finally for high NA = 18 or above. Wilson Sex Fantasy Questionnaire. The WSFQ-test (Wil- son, 1978) consists of 40 examples of sexual fantasies. Re- spondents may indicate how often they have a sexual fantasy, on a six-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 5 (regularly). The fantasies are divided into four groups with ten imaginative ex- amples in each. The categories are Exploratory, Impersonal, Intimate, and Sado-masochistic. Examples of the exploration category are “Being promiscuous” and “Incestuous relation- ships”. Examples of the impersonal category are “Watching other people having sex” and “Using objects for stimulation (e.g., vibrators). Examples of the intimate category are “Love in the romantic surroundings” and “Sexual intercourse with loved partners.” Examples of the sado-masochistic category are: “Be bound” and “Whip or spank someone.” The sum of the respon- dents score on all four types of imagination also gives a meas- ure of how often he/she has sexual fantasies at all. This fifth variable is here called Fantasy-fluency. Cronbach’s alpha for Fantasy-flue ncy in the cu r rent study was .91. Procedure Questionnaires with a cover sheet with instructions, back- ground data and the tests were distributed to students who wanted to participate. This was primarily done by asking them when they dwelt or passed through one centrally located large  M. CARLSTEDT ET AL. 794 open space at the university. This space includes a cafe and is crowded especially at lunchtime. Through using screens was it possible to organize a demarcated area. Then people who passed were asked whether or not they wanted to participate in the survey. Those who accepted were headed to the demarcated area where they were allowed to complete the questionnaire. Approximately one in five people, who were approached, ac- cepted to participate in the study. Two individuals decided to terminate participation after first h a v i n g accepted participati o n. When it seemed reasonably to suspect that people who vol- untarily agree to complete a questionnaire concerning their sexual fantasies during their lunch break, may be more sexually outspoken than those who abstain, the theme of sexual fantasies was not mentioned when potential respondents were ap- proached. They were instead asked to participate in a study dedicated to “Affectivity and Fantasy”. It was only when they had the opportunity to read the survey cover letter that they found out that it was about sexual fantasies. They then also received the information that they had the right at any time to discontinue participation and to do that without having to jus- tify themselves. The questionnaires were completed anony- mously and respondents submitted their questionnaires in a sealed box. In order to provide as much privacy as possible, it was never more than five respondents in the demarcated area at the same time. For further privacy respondents were given writing pads so they did not have to crowd around the tables. They were also asked to place themselves as far apart as from each other as possible. Statistical analyses were performed by using the statistical software SPSS, version 18. Results Affective Personality and Gender in Regard to WSFQ A Pillais’ MANOVA (4 × 2 factorial design) was conducted with Affective personality and Sex of participants as independ- ent variables and with the WSFQ scales (i.e., Exploratory, Im- personal, Intimate, Sado-masochistic and Fantasy-fluency) as dependent variables. The analysis yielded significant effects for Affective personality (p = .024, Eta2 = .08, power = .92) and for Sex of participants (p = .003, Eta2 = .08, power = .92), but not the interaction (p = .108, Eta2 = .03, power = .82). The results from the univariate F-tests concerning Affective person- ality and Sex of participants are given below. For means and standard deviations see Table 1. Affective personality. Univariate F-tests showed significant effects for Exploratory [F (3, 200) = 3.25, p = .023], Impersonal [F (3, 200) = 7.04, p < .001], and for Fantasy-fluency [F (3, 200) = 4.49, p = .004]. Post hoc testing (Tukey-HSD, 5% level) showed that concerning Exploratory high affective and self- destructive participants scored higher as compared to the self- actualizing, whereas the low affective fell in between. Con- cerning Impersonal the self-destructive and the high affective had more fantasies than both the self-actualizing and the low affective. Finally, regarding Fantasy-fluency the same pattern was repeated i.e., the self-destructive and the high affective had more fantasies than both the self-actualizing and the low affec- tive. Sex of participants. Univariate F-tests showed significant effects for Exploratory [F (1, 200) = 9.43, p = .002] and Imper- sonal [F (1, 200) = 4.93, p = .027]. Descriptive analysis showed that men scored higher compared to women for both Explora- tory and Impersonal. Low and High PA and NA in Regard to WSFQ The above performed analysis indicated that affective per- sonality types with high negative affectivity (i.e., High affective and Self-destructive) were the ones who experienced most sex- ual fantasies. In order to further investigate this relationship a Pillais’ MANOVA (2 × 2 factorial design) was conducted with Positive affectivity (low, high) and Negative affectivity (low, high) as independent variables and with the WSFQ scales (i.e , Exploratory, Impersonal, Intimate, Sado-masochistic and Fan- tasy-fluency) as dependent variables. The analysis revealed significant effects of Negative affectivity (p = .001, Eta2 = .09, power = .96) but not for Positive affectivity (p = .717, Eta2 = .01, power = .18) or interaction (p = .767, Eta2 = .01, power = .16). The results of the univariate F-tests in regard to Nega- tive aff ectivity are giv en below. For mean s and standard dev ia- tions see Table 2. Univariate F-tests showed significant effects for Exploratory [F (1, 205) = 10.27, p = .002], Impersonal [F (1, 205) = 20.17, p < .001], Intimate [F (1, 205) = 5.70, p = .018], Sado-masochis- tic [F (1, 205) = 7.30, p = .007], and Fantasy-fluency [F (1, 205) = 15.75, p < .001]. Post hoc-testing (Tukey-HSD, 5% level) showed the same pattern for all dependent variables i.e., par- ticipants with high Negative affectivity had more sexual fanta- sies. A subsequent comparison between the two personality types with high negative affectivity on item level showed (Mann-Whitney U-test, 5% level) only significant differences for three items where the High affective had more romantic oriented fantasies compared to the Self-destructive (“love out- doors in the romantic surroundings”, “sexual intercourse with a Table 1. Means and (standard devia tions ) for affective personality (self-destructive, low affective, high affective, self-actualizing) and gender (man, women) in regard to the WSFQ scales (exploratory, impersonal, intimate, sado-masochistic, fantasy-fluency). Self-destructive Low affective High affective Self-actualizing Man Wom Man Wom Man Wom Man Wom Exploratory 15.74 (9.44) 7.47 (6.37) 10.08 (3.99) 6.27 (6.75) 13.25 (6.72) 10.61 (6.56) 8.00 (3.74) 6.68 (5.84) Impersonal 13.89 (8.83) 7.43 (5.22) 5.50 (3.12) 5.27 (6.01) 11.60 (6.14) 9.20 (5.08) 6.50 (4.43) 5.45 (5.40) Intimate 30.79 (8.70) 25.51 (9.60) 22.42 (9.19) 27.27 (8.34) 28.65 (8.16) 30.89 (7.74) 31.00 (10.80) 24.77 (12.42) Sado-masoc 6.42 (8.64) 4.35 (5.62) 1.42 (1.68) 3.80 (6.33) 4.80 (5.40) 6.50 (7.31) 3.50 (3.42) 2.95 (4.45) Fantasy-flu 66.84 (27.85) 44.76 (20.54) 39.42 (13.37) 42.60 (22.98) 58.30 (22.06) 57.20 (20.19) 49.00 (18.20) 39.86 (24.16)  M. CARLSTEDT ET AL. 795 Table 2. Means and (standard deviations) for low and high positive affectivity (PA) and low and high negative affectivity (NA) in regard to the WSFQ scales (exploratory, impersonal, intimate, sado-masochistic, fantasy- fluency). PA NA Low High Low High Exploratory 10.29 (8.29) 10.18 (6.65) 7.43 (5.70) 11.20 (7.92) Impersonal 9.06 (7.37) 8.75 (5.71) 5.49 (4.98) 10.10 (6.78) Intimate 27.15 (9.43) 28.94 (9.40) 25.42 (10.55) 28.80 (8.90) Sado-masoc 4.66 (6.72) 5.26 (6.35) 2.89 (4.56) 5.62 (6.98) Fantasy-flu 51.16 (25.25) 53.13 (22.46) 41.23 (21.01) 55.71 (23.92) beloved partner”, “passionate kissing”). Discussion The study showed a connection between Affective personal- ity and sexual fantasies, namely that the self-destructive and high affective individuals had more sexual fantasies compared with the self-actualizing and low affective. The relationship was significant in two out of four of the WSFQ subscales and Fantasy fluency that is the total score. The high affective and the self-destructive personality types have in common that they both are high on negative affectivity. Follow-up analysis also showed that people with high negative affectivity had significantly more fantasies on all five depend- ent variables compared to those with low negative affectivity, while there was no difference in terms of high and low positive affectivity. Previous research shows no conclusive results. Green and Mosher (1985) demonstrated that negative affectivity had an inhibitory effect on sexual responses, and promoted sexual arousal on one of five variables. Heiman and Hatch (1980) reported that both positive and negative affectivity may pro- mote sexual arousal. Arndt et al. (1985) found positive rela- tionships between frequency of sexual fantasies and sexual responses. One explanation contradictive results may be that different personality types differ in the way they report their experiences. Individuals who are characterized by high negative affectivity often have more introspective personalities (Woodhouse, & Gelso, 2008), which may lead to that they more easily can de- tect and remember their sexual fantasies. This hypothesis would also shed some light on the imbalance in the sample of the cur- rent investigation. The breakdown of the different personality types was made according to the Swedish norm group (Nor- lander et al., 2005), but only about one quarter of the respon- dents were low affective or self-actualizing. The respondents had significantly more negative affectivity as compared to the Swedish norm group. The reason for this may be that individu- als with an “introspective orientation” are more likely to take five minutes of their lunch hour to answer questions about emotions and imagination. Another explanation may be derived from the previously identified (Woodhouse, & Gelso, 2008) connection between Attachment orientation and negative affectivity that is, those having an anxious attachment are also higher on NA. People with anxious attachment also exhibits generally higher fre- quency of sexual fantasies, something they have in common with the self-destructive and the high affective groups in the present study. The result may therefore indicate that self-de- structive and high affective individuals are inclined to anxious attachment. It is suggested (Birnbaum, 2007) that individuals with anxious attachment orientation uses sexual fantasies in order to satisfy their needs for security, closeness and affirma- tion. Also the need for novelty and variety (Leitenberg & Hen- ning, 1995) and aggression (Heiman & Hatch, 1980) may be channeled into sexual fantasies. Finally, self-destructive and high affective personality types report higher levels of stress (Bood, et al., 2004) than the self-actualized and low affective types, which could possibly imply the existence of a mecha- nism in which sexual fantasies acts as a valve for frustrations caused by stress. Men had significantly higher scores on Exploratory and Im- personal compared to women which is in line with many other studies (e.g., Leitenberg & Henning, 1995; Wilson, 1978). There was no significant difference between men and women in regard to Fantasy-fluency which is in conflict with several pre- vious studies where men tend to have more sexual fantasies than women (Wilson, 1978). One explanation for this may be sample composition with an over-representation of self-de- structive and high affective participants. This may also reflect the main limitation of the present study, which was that par- ticipants were not randomly selected from a larger sample, but recruited by asking them as they passed a cafeteria. The present investigation was not concerned with sexual arousal but rather sexual fantasies. As already stated, positive affectivity promotes sexual responses (Green & Mosher, 1985; Heiman and Hatch, 1980). A sexual response could be consid- ered a response to external stimuli. Thus, it would be possible to formulate the hypothesis that positive affectivity affects an “external transparency”, a susceptibility to stimuli from the outside world, while negative affectivity affects an “internal transparency”, a tendency to look inward, reflect and fantasize. References American Psychiatric Association (1995). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.) . Washington, DC. Arndt, W. B., Foel, J. C., & Good, F. E. (1985). Special sexual fantasy themes: A multidimensional study. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 48, 472-480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.2.472 Arndt, W. B., & Ladd, B. (1981). Sibling incest aversion as an index of oedipal conflict. Journal of Personality Assessmen t, 4 5, 52-58. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4501_11 Bäccman, C., Folkesson, P., & Norlander, T. (1999). Expectations of romantic relationships: A comparison between homosexual and het- erosexual men with regard to Baxter’s criteria. Social Behavior and Personality, 27, 363-374. Birnbaum, G. E. (2007). Beyond the borders of reality: Attachment orientations and sexual fantasies. Personal Relationships, 14, 321- 342. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00157.x Bood, S. Å., Archer, T., & Norlander, T. (2004). Affective personality in relation to general personality, self-reported stress, coping, and optimism. Individual Differences Research, 2, 26-37. Cogan, R., Cochran, B. S, Velarde, L. C., Calkins, H. B., Chenault, N. E., Cody, D. L., Kelley, M. D., Kubicek, S. J., Loving, A. R., Noriega, J. P., Phelan, K. A, Siege, S. C, Stout, T. I, Styles, J. W., & Williams, H. A. (2007). Testing Freud’s hypothesis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 24, 697- 700. doi:10.1037/0736-9735.24.4.697 Green, S. E., & Mosher, D. L. (1985). A casual model of sexual arousal to sexual fantasies. Th e J ou r n al o f S ex Research, 21, 1-23. doi:10.1080/00224498509551241 Guilford, J. P., Guilford, J. S., & Zimmerman, W. S. (1978). The Guil- ford-Zimmerman Temperament Survey. CA: Sheridan Psychological  M. CARLSTEDT ET AL. 796 Services. Hariton, E. B., & Singer, J. L. (1974). Women’s fantasies during sexual intercourse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 313- 322. doi:10.1037/h0036669 Heiman, J. R., & Hatch, J. P. (1980) Affective and physiological di- mensions of male sexual response to erotica and fantasy. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 4, 315-327. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0104_3 Leitenberg, H., & Henning, K. (1995). Sexual fantasy. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 469-496. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.469 Norlander, T., Bood, S. Å., & Archer, T. (2002). Performance during stress: Affective personality, age, and regularity of physical exercise. Social behavior and P ersonality, 30, 495-508. doi:10.2224/sbp.2002.30.5.495 Norlander, T., Johansson, Å., & Bood, S. Å. (2005). The affective personality: It’s relation to quality of sleep, well-being and stress. Social Behavior and Personality, 33, 709-722. doi:10.2224/sbp.2005.33.7.709 Norlander, T., von Shedvin, H., & Archer, T. (2005) Thriving as a function of affective personality: relation to personality factors, cop- ing strategies and stress. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 18, 105-116. doi:10.1080/10615800500093777 Perrin-Wallqvist, R., Eriksson, E., & Norlander, T. (2001). The effects of alcohol intake and induced frustration on the disposition to start fires. Social Behavior and Personality, 29, 547-556. doi:10.2224/sbp.2001.29.6.547 Tidefors-Andersson, I. (2000). Den fördömda handlingen: Sexuella övergrepp mot barn [The condemned act: sexual abuse of children]. Göteborg: Psykologisk a Institutionen, Göt eborgs Universitet. Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 Wilson, G. D. (1978). The secrets of sexual fantasy. London: J. M. Dent & Sons ltd. Wilson, G. D. (1997). Gender differences in Sexual fantasy: An evolu- tionary analysis. Personality and Individual Differenc es, 22, 27-31. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00180-8 Wilson, K., Gullone, E., & Moss, S. A. (1998). The Youth Version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: A psychometric valida- tion. Behavior Change, 15, 187-193. Woodhouse, S. S., & Gelso, C. J. (2008) Volunteer client adult attach- ment, memory for insession emotion, and mood awareness: An affect regulation perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 197- 208. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.197 |