Theoretical Economics Letters, 2011, 1, 57-62 doi:10.4236/tel.2011.13013 Published Online November 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/tel) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. TEL Licensing Contracts in Hotelling Structure Tarun Kabiraj1, Ching Chyi Lee2 1Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India 2The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China E-mail: tarunkabiraj@hotmail.com Received June 1, 2011; revised August 11, 2011; accepted August 22, 2011 Abstract This paper discusses the question of optimal licensing contracts in Hotelling structure and focuses on the unique features of this structure in this context. We show that a royalty equilibrium exists if and only if transport cost lies in a specified interval, but the royalty rate can be higher than the amount of cost saving. While fee licensing only is never profitable, the optimal licensing contract consists of both fee and royalty. In equilibrium the market is fully covered with monopolistic goods. Keywords: Technology Transfer, Royalty Licensing, Fee Licensing, Hotelling Structure 1. Introduction Technology transfer from a low cost firm to a high cost firm is a common phenomenon. By transferring its supe- rior technology the patent holder can achieve a larger profit. There is already a vast literature on technology licensing. One aspect of this literature is to discuss the question of optimal licensing contracts1. Generally tech- nology transfer occurs under a fee contract or royalty contract, and sometimes the contract takes a hybrid form consisting of both fee and royalty2. However, which par- ticular form of contract is optimal from the viewpoint of the transferor depends on a number of factors such as: the structure of the product market, the nature of market competition, the degree of product differentiation, the extent of cost saving, whether the patentee is an insider or outsider, whether there is asymmetric information, etc. Given the existing literature, it seems that the question of technology licensing in the Hotelling [5] structure is not yet fully explored. One motivation of the present paper is to draw attention to the special features of the Hotelling model in this context as distinct from the other models of product differentiation. The important ques- tions we like to discuss in this paper are the following. Can there be a technology transfer under a fee contract? Does a royalty contract always exist? Is the market fully covered under the optimal licensing contract? Can the optimal royalty rate exceed the extent of cost saving? Can the transferor extract all surplus of the transferee by means of a royalty alone? Is such transfer beneficial to the consumers? We restrict our analysis to the scenario where the patentee is an insider and firms’ locations are exogenous. Initially the firms have asymmetric tech- nologies. The low cost firm then designs a contract to transfer its technology to the other firm. To our knowledge, only two papers, Poddar and Sinha [6] and Matsumura and Matsushima [7], have provided some analysis on the issue of technology licensing in Hotelling structure. While Poddar and Sinha discuss the question of optimal licensing contracts between the two firms, their solution for a royalty contract is incorrectly formulated. And Matsumura and Matsushima examine how licensing activities affect the location of the firms and their incentives for R & D investment. Both the pa- pers assume a priori that a royalty cannot exceed the amount of cost saving, but neither explains why such an assumption is needed. In our paper we investigate this issue when the royalty rate is endogenously determined. Further, in our analysis there is an outside good; hence we examine whether in equilibrium the market is fully covered with the monopolistic good. In all the models, however, fee licensing is never profitable. The main results derived in the paper are the following, and it may be pointed out that some of these results are driven by the unique qualities of the Hotelling model of duopoly. For instance, we show that the optimal output and profit levels are independent of the marginal cost of production when the firms are equally efficient; so with 1See, for instance, Kabiraj [1], Sen and Tauman [2]), and Mukherjee [3]. 2In a survey of firms, Rostoker [4] finds that 39% of cases have royalty alone, 13% have fee alone and the remaining cases have fee plus roy- alty.  T. KABIRAJ ET AL. 58 technology transfer marginal cost has no effect on the equilibrium levels of market share or firm profits. In ad- dition, under transfer the transferee’s profit is unaffected by the royalty rate and the transferor’s profit is linear in royalty rate. In no other differentiated product models we have these features. In our paper the transport cost plays an important role in determining and characterizing the licensing equilibrium. A royalty licensing equilibrium exists if and only if the transport cost belongs to a speci- fied interval. In equilibrium the market is fully covered; thus segmented market equilibrium will never occur. The optimal royalty rate when licensing equilibrium exists can be higher than the amount of cost reduction. Since the transferor cannot extract all surplus of the transferee by means of a royalty only, a royalty-fee contract is op- timal in the Hotelling structure. To briefly outline the literature in his context, we note that in a homogeneous good duopoly, with the patentee being insider, in equilibrium royalty licensing dominates fee licensing and the optimal royalty is equal to the amount of cost saving (Wang [8]). Then if the model is extended to the case of usual Dixit [9] type product dif- ferentiation, qualitative results remain almost unchanged (Wang [10]). One distinctive result, however, is that a drastic innovation may be transferred when the goods are imperfect substitute. Li and Song [11] have studied technology licensing in a vertically differentiated du- opoly. It is shown that the high-quality firm always transfers its superior technology to the low-quality firm, irrespective of the forms of the licensing contracts. Fi- nally, Kabiraj and Lee [12] have shown that when the products are both vertically and spatially differentiated a fee licensing can be a profitable option. The layout of the paper is the following. In section 2 we present the model and results. Finally, section 3 is a conclusion. 2. Model and Results Consider two firms producing homogeneous goods but located at two end points of a Hotelling linear city of length 1. Assume that firm 1 is located at 0 and firm 2 at 1. Consumers are uniformly distributed over the length of the city; each consumer buys at most one unit of the monopolistic good. We say that the market is fully cov- ered if all consumers buy the good. Assume further that there is an outside competitive good, and the consumer’s net utility from it is normalized to zero. Therefore a consumer will buy the monopolistic good if and only if her net utility from it is non-negative. The utility function of a consumer located at is given by [0,1]x 1 2 if tobuyfromfirm1 (1) iftobuyfromfirm2 vtxp uvtx p where denotes the basic utility, same for all con- sumers; i is the unit price charged by firm , and is the Hotelling transport cost of travel per unit distance. We restrict to the scenario where each firm has a positive market share; therefore, 0v pi 0t i; jj ptpptij . Let be the consumer indifferent between buying from firm 1 and firm 2, 21 1 2 tp p t Then the market is fully covered if and only if 12. This gives demand for firm 1 and firm 2’s product as 2vp pt 11 2 (, )Dpp x and 212 (, )1Dpp x , respectively. On the other hand, the market is segmented if 12 2vp pt . This is the situation when some consumers (in particular, the one located at ) fail to buy the monopolistic product. In this case firm i (i1, 2 ) faces the demand, i ii () vp Dp t . Let i be the unit cost of production of firm . Fur- ther assume that firm 2 possesses the superior technology; therefore, 21 ci cc . We consider the possibility of tech- nology transfer from firm 2 to firm 1. First we consider the benchmark case of no technology transfer. Then we examine fee licensing and royalty licensing separately. Finally we discuss the optimal licensing contract. 2.1. Benchmark Case: No-Transfer of Technology Given the demand and cost functions, firm i’s profit function is: i12i i i12 (, )()(, )ppp cDpp i1,2 We assume that both the firms have positive market shares. The firms simultaneously choose their prices, hence they play a Bertrand-Nash game. The equilibrium prices, market shares and profits of the firms are 112 132 3 N ptcc, 21 132 3 N ptc 2 c 12 13 6 NN Dx tcc t1 , 21 1 13 6 NN Dx tc t 2 c 2 121 1 π3 18 Ntc c t , 2 21 1 π3 18 Ntc c t 2 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. TEL  59 T. KABIRAJ ET AL. Then, the assumption that each firm has a positive mar- ket share means that 12 3 cc t t (1) 2.2. Technology Transfer under a Fee Contract Here the game is the following. Firm 2 offers a fee con- tract to firm 1. If it is accepted, the superior technology is transferred and the market structure becomes symmetric duopoly, with each firm having low unit cost of produc- tion. And if the contract is rejected (this is equivalent to giving a no-technology transfer offer), the market struc- ture becomes asymmetric duopoly as given in the ben- chmark model. Now the market-operated profits of the firms under the fee licensing contract are: 12 ππ 2 F t Then technology transfer under the fixed fee contract will be mutually profitable if and only if 22 ππ N F and 1 π1 π N F . Then if and only if 0F 121 ππ ππ 2 FN N But this condition is never satisfied. Hence in the Ho- telling structure fee licensing will never occur in equilib- rium3. 2.3. Technology Transfer under a Royalty Contract Now consider the possibility of technology transfer from firm 2 to firm 1 under a royalty contract. The game is the following. First, firm 2 proposes a royalty, , per unit of firm 1’s output. In the second stage firm 1 either accepts or rejects the contract; it accepts if it is not worse off in the post-transfer situation. Then in the third stage they choose prices simultaneously. Therefore, rejecting the contract means it is no-transfer equilibrium outcome. r First consider royalty equilibrium with full market coverage. Given any , the third stage problems of firm 1 and firm 2 are respectively, r 1 12 112 max ()(,) ppcrDpp and 2 22 212112 max ()(,)(,) ppcDpp rDpp The third stage outcomes are: 12 2 () () RR prprtc r 12 1 ()() 2 RR Dr Dr 1 π() 2 Rt r and 2 π() 2 Rt rr Recall that the assumption of full market coverage re- quires that , i.e., 12 2()() RR vpr prt 2 3 2 rvc tr (2) We further need to restrict that , i.e., 0 R r 2 2() 3 tvct (3) Note the unique features of the Hotelling structure in licensing equilibrium. Here 1 D, 2 D and 1 π are in- dependent of , but 1 r p, 2 p and 2 π are linear and increasing in . Hence firm 2 has an incentive to in- crease as much as possible; in response firm 1 will just raise its price linearly without losing its market share and profits as long as the indifferent consumer r r con- tinues to buy. Therefore, the optimal royalty r is de- termined corresponding to () 0ux. This gives 2 3 2 R rvc t (4) Given that tt (which ensures that both the firms’ market shares are positive and profits are strictly posi- tive), we have 11 π() π N r. Therefore, in the second stage any royalty rr is acceptable to firm 1. Given (4), there are parameter values under which 12 is possible; therefore the royalty rate can exceed the amount of cost saving. () R rcc 0 Now firm 2 will offer the royalty r iff 22 ˆ π() π N r, that is 2 12 1(3 ) 218 Rt rtc t c 2 12 12 2 ()( 3 () 23 18 () cc cc LHS tvctt RHS t ) (5) Check that is linear anddecreasing in , and is convex and decreasing, with ()LHS tt ()RHS t 12 ()cc () 3 RHS t as , and t () ()LHS tRHS t. Therefore, ˆˆ , , |LHS()RHS() (,)tt ttttttt ˆ (6) This is shown in Figure 1. Thus royalty equilibrium is the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium outcome of this game if the transport cost lies in the specified interval. This gives the first result of our paper. 3This result is already derived in Poddar and Sinha [6]. However, fee licensing can be profitable if the products are both vertically and hori- zontally differentiated (Kabiraj and Lee [12]). Proposition 1: Technology transfer under the royalty contract with full market coverage is mutually profitab le Copyright © 2011 SciRes. TEL  T. KABIRAJ ET AL. 60 Figure 1. Transport cost and licensing contracts. if and only if ˆ (, )ttt. The optimal royalty rate is r. It also follows from the proposition that there will be no royalty licensing with full market coverage if . To examine the possibility of royalty equilibrium when the market is not fully covered, we need to restrict to the scenario where in equilibrium, 12 . We have derived the following result. The proof is given in the Appendix. ˆ tt t2vpp Proposition 2: In the royalty model discussed above, there exists no equilibrium in which the market is not fully covered. Further note that 0 12 2 3 2( 4 vp pttvct) (see (A1) in the Appendix), and then we have, 0 ˆ tt . Therefore, in the Hotelling structure if royalty licensing is ever mutually profitable to the firms, it is always op- timal to cover the market fully, and such an equilibrium will exist if and only if ˆ (, )ttt. Proposition 3: In a Hotelling structure with uniform distribution of consumers, the op timal royalty contract is r, and in equilibrium, the market is fully covered. 2.4. The Optimal Licensing Contract Consider the full game. First, firm 2 decides whether to license its technology to its product market rival. If to transfer, it decides whether to offer a fee licensing con- tract, a royalty licensing contract or a mixture of both. Finally the firms compete in prices. So we search for the subgame perfect equilibrium outcome of this game. We have already shown that under spatial competition with uniform distribution of consumers, a fee licensing is never profitable. And a royalty contract, when it is prof- itable, leaves a surplus profit for the transferee, because 11 () π N r . Can the transferor extract this surplus by a mixture of both royalty and fixed fee, that is, by offering a royalty-fee contract ? It is easily understood that the optimal royalty and fixed fee will be (, )rF r and , where 12 12 11 ()(6 π() π 18 RR N cc tcc Fr t ) 2 (7) Then firm 2’s profitability condition becomes 22 π(, )π() π RRRRRN rFr F 2 12 2 2( ) 3 () () 218 cc LHStvctRHSt t (8) This is satisfied4 for all ˆ (, )ttt where ˆˆ tt t , as shown in Figure 1. This gives the final result of the paper: Proposition 4: Given ˆ (, )ttt , the optimal licens- ing contract under spatial competition is (, ) R rF ; there will be no licensing if ˆ (, )ttt . Note that the availability of a hybrid contract in fact relaxes the constraint of technology transfer, because now the interval of becomes bigger. t 3. Conclusions In the Hotelling structure fee licensing is never profitable, but a royalty equilibrium always exists if the transport cost lies in a specified interval. The unique feature of the Hotelling structure is that under technology transfer the transferee’s profit is independent of the royalty rate and the transferor’s payoff is a linear function of the royalty rate. Therefore, if there is no restriction on the upper bound of royalty, the transferor, under the optimal li- censing contract, raises the royalty as high as possible subject to the marginal indifferent consumer deriving zero utility. However, a royalty-fee contract is required if to extract all surplus of the transferee. In any case, in equilibrium the market is fully covered. Finally, to make a comment on consumers’ welfare we may note that in royalty equilibrium all consumers buy the monopolistic good, but they are to pay a higher price for the good in the post-transfer equilibrium. Then to protect the interest of the consumers in such a situation an upper restriction on the royalty rate is perhaps needed. 4. Acknowledgements 4Note that 12 () () ()6 cc RHS tRHS tt . We are greatly indebted to the referee of this journal for Copyright © 2011 SciRes. TEL  T. KABIRAJ ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. TEL 61 his valuable suggestions and comments on the earlier draft. We shall, however, be held responsible for any re- maining errors. 5. References [1] T. Kabiraj, “Technology Transfer in a Stackelberg Struc- ture: Licensing Contracts and Welfare,” The Manchester School, Vol. 73, No. 1, 2005, pp. 1-28. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9957.2005.00421.x [2] D. Sen and Y. Tauman, “General Licensing Schemes for a Cost-Reducing Innovation,” Games and Economic Be- havior, Vol. 59, No. 1, 2007, pp. 163-186. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2006.07.005 [3] A. Mukherjee, “Competition and Welfare: The Implica- tions of Licensing,” The Manchester School, Vol. 78, No. 1, 2010, pp. 20-40. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9957.2009.02126.x [4] M. Rostoker, “A Survey of Corporate Licensing”, IDEA: The Journal of Law and Technology, Vol. 24, No. 2, 1984, pp. 59-92. [5] H. Hotelling, “Stability in Competition,” Economic Jour- nal, Vol. 39, No. 153, 1929, pp. 41-57. doi:10.2307/2224214 [6] S. Poddar and U. Sinha, “On Patent Licensing in Spatial Competition,” The Economic Record, Vol. 80, No. 249, 2004, pp. 208-218. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4932.2004.00173.x [7] T. Matsumura and N. Matsushima, “On Patent Licensing in Spatial Competition with Endogenous Location Choice,” 2008. http://www.iss.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~matsumur/LI.pdf [8] X. H. Wang, “Fee versus Royalty Licensing in a Cournot Duopoly Model,” Economics Letters, Vol. 60, No. 1, 1998, pp. 55-62. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(98)00092-5 [9] A. Dixit, “A Model of Duopoly Suggesting a Theory of Entry Barriers,” Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1979, pp. 20-32. doi:10.2307/3003317 [10] X. H. Wang, “Fee versus Royalty Licensing in a Differ- entiated Cournot Duopoly,” Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 54, No. 2, 2002, pp. 253-266. doi:10.1016/S0148-6195(01)00065-0 [11] C. Li and J. Song, “Technology Licensing in a Vertically Differentiated Duopoly,” Japan and the World Economy, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2010, pp. 183-190. doi:10.1016/j.japwor.2008.04.002 [12] T. Kabiraj and C. C. Lee, “Technology Transfer in a Du- opoly with Horizontal and Vertical Product Differentia- tion,” Trade and Development Review, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2011, pp. 19-40.  T. KABIRAJ ET AL. 62 Appendix To examine the possibility of royalty equilibrium when the market is not fully covered let us restrict to the scenario where in equilibrium, . 12 Consider local monopoly of firm 1 under technology transfer. For any acceptable , firm 1’s problem is: 2vp pt r 1 1 12 max () p vp pcrt The corresponding product price and market share of firm 1 are, respectively, 12 1 () () 2 prvcr and 1 1 () () 2 Drv cr t 2 r Since now two markets are segmented, the licensing revenue maximizing royalty rate will be , where 1 r argmax( )rrD 2 vc 2 r The corresponding equilibrium price, market share and profit of firm 1 are: 12 1 () (3) 4 prvc , 12 1 () () 4 Drv c t and 2 12 1 π()( ) 16 rvc t and the royalty income of firm 2 is, 2 12 1 () () 8 rD rvc t Firm 2’s profit from its segmented market is solved from: 2 2 22 max () p vp pc t This gives: 22 1() 2 pvc , 12 1() 2 Dvc t and 2 22 1 π() 4vc t Hence, firm 2’s total payoff under royalty licensing is: 2 22 12 3 π() () 8 rD rvc t Finally, the licensing contract with local monop- oly will be an equilibrium contract iff the following three conditions hold simultaneously. First, the assumption that each firm has local monopoly requires , i.e., r 12 2vp pt 0 2 3() 4 tvct 1 (A1) Second, the contract on is acceptable to firm 1 iff , i.e., r 0 1 π() πr 212 1 3 22 vcc c tt 2 (A2) Third, offering the licensing contract is profitable to firm 2 iff r 0 2 π , i.e., 12 2 3 23 cc tvc 2 t (A3) These three conditions (A1) through (A3) will be satis- fied simultaneously iff 0 12 min{ ,}tt t (A4) Therefore, 2 tt 1 12 2 3(232) () 42 cc vc 3 Finally, we can check that ; therefore con- dition (A4) is never satisfied. This proves Proposition 2. 0 12 min{ ,}ttt Copyright © 2011 SciRes. TEL

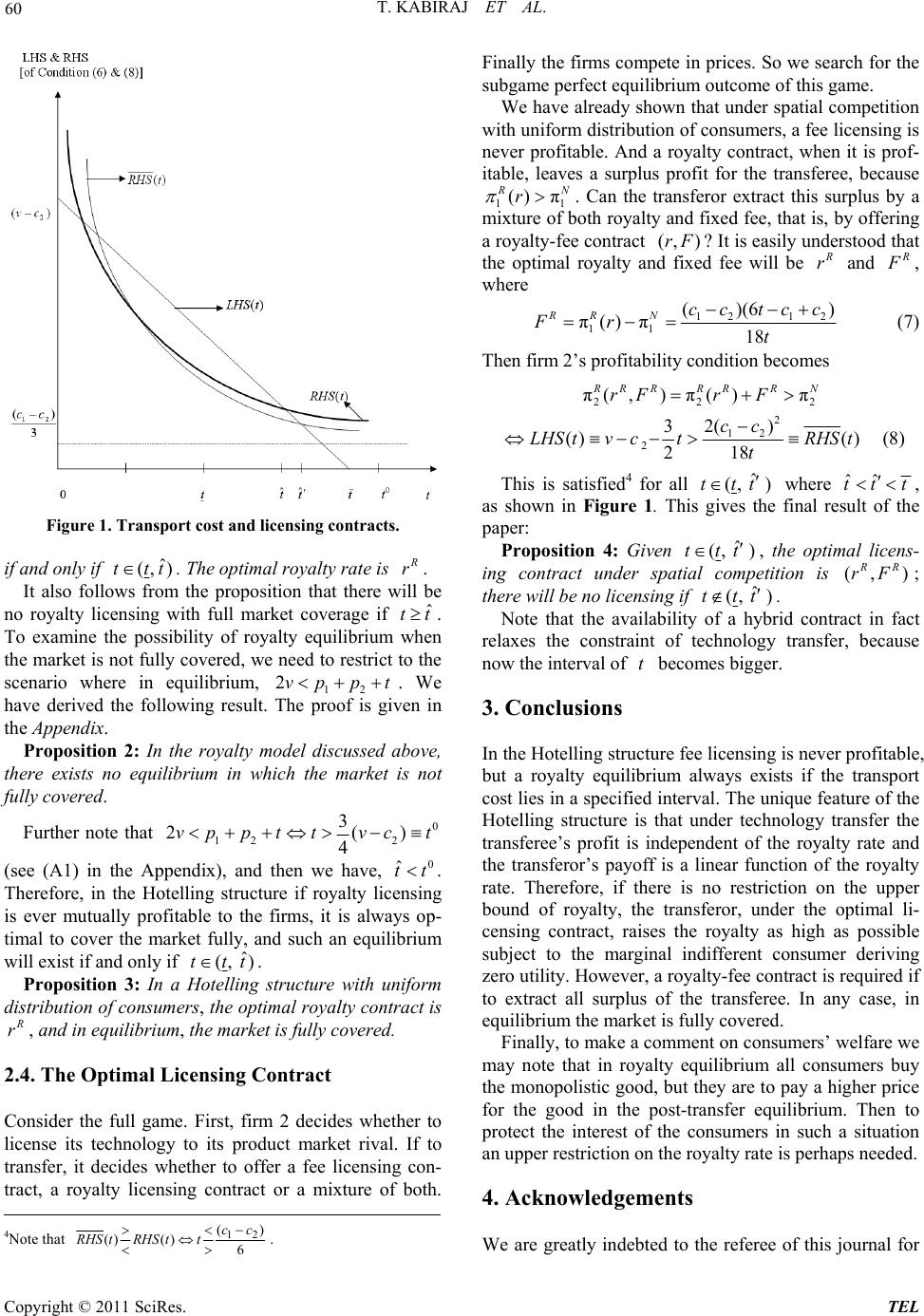

|