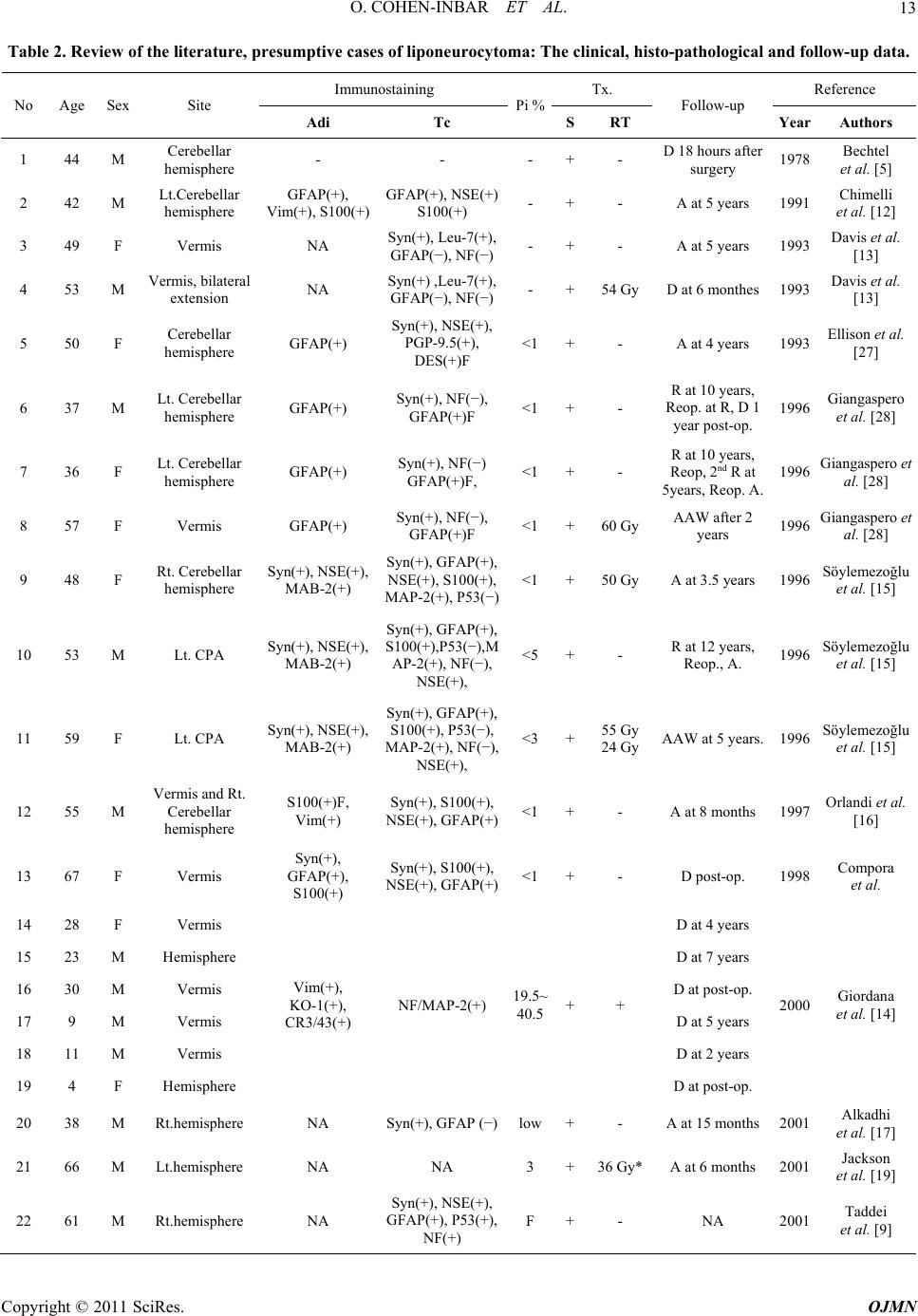

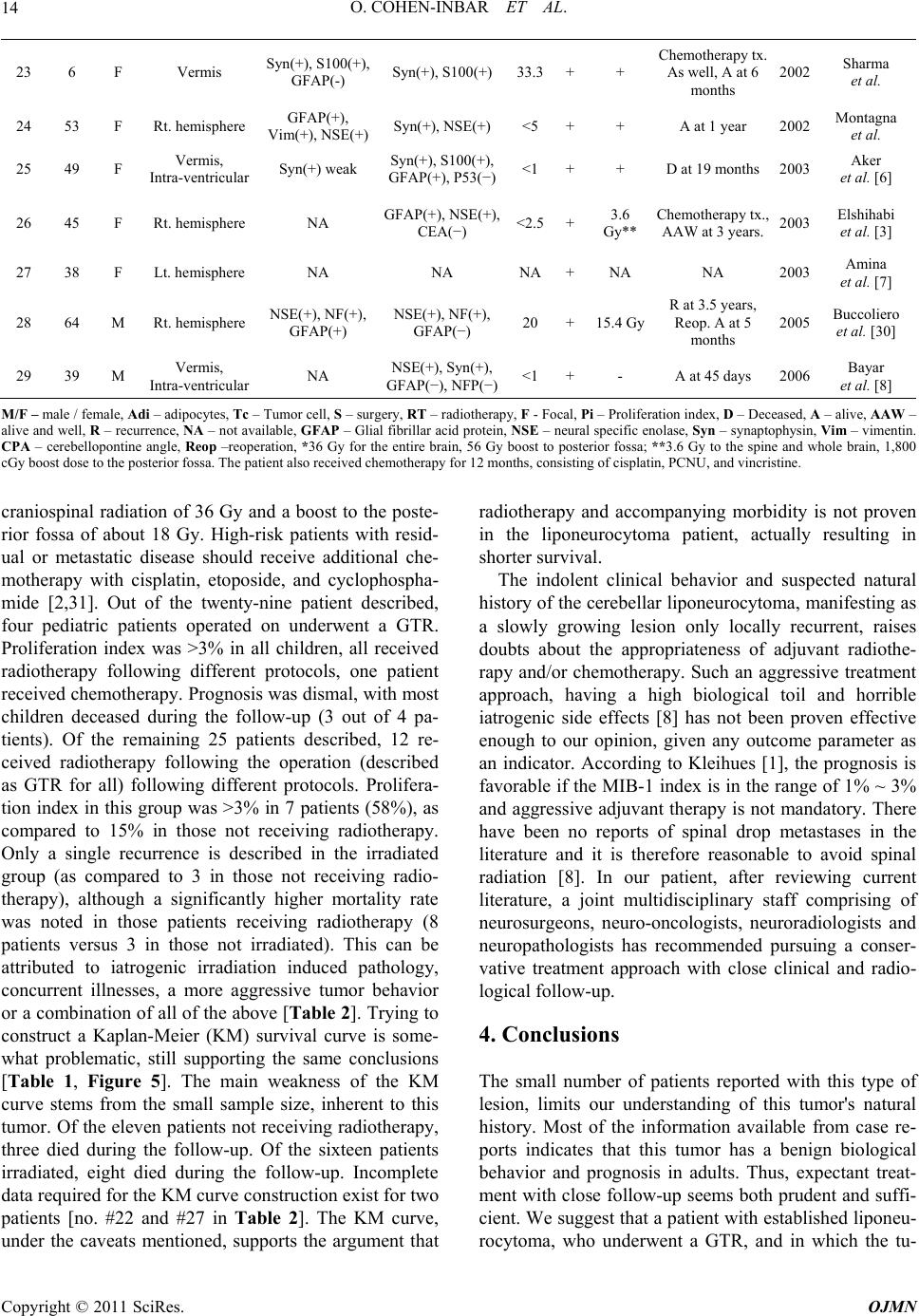

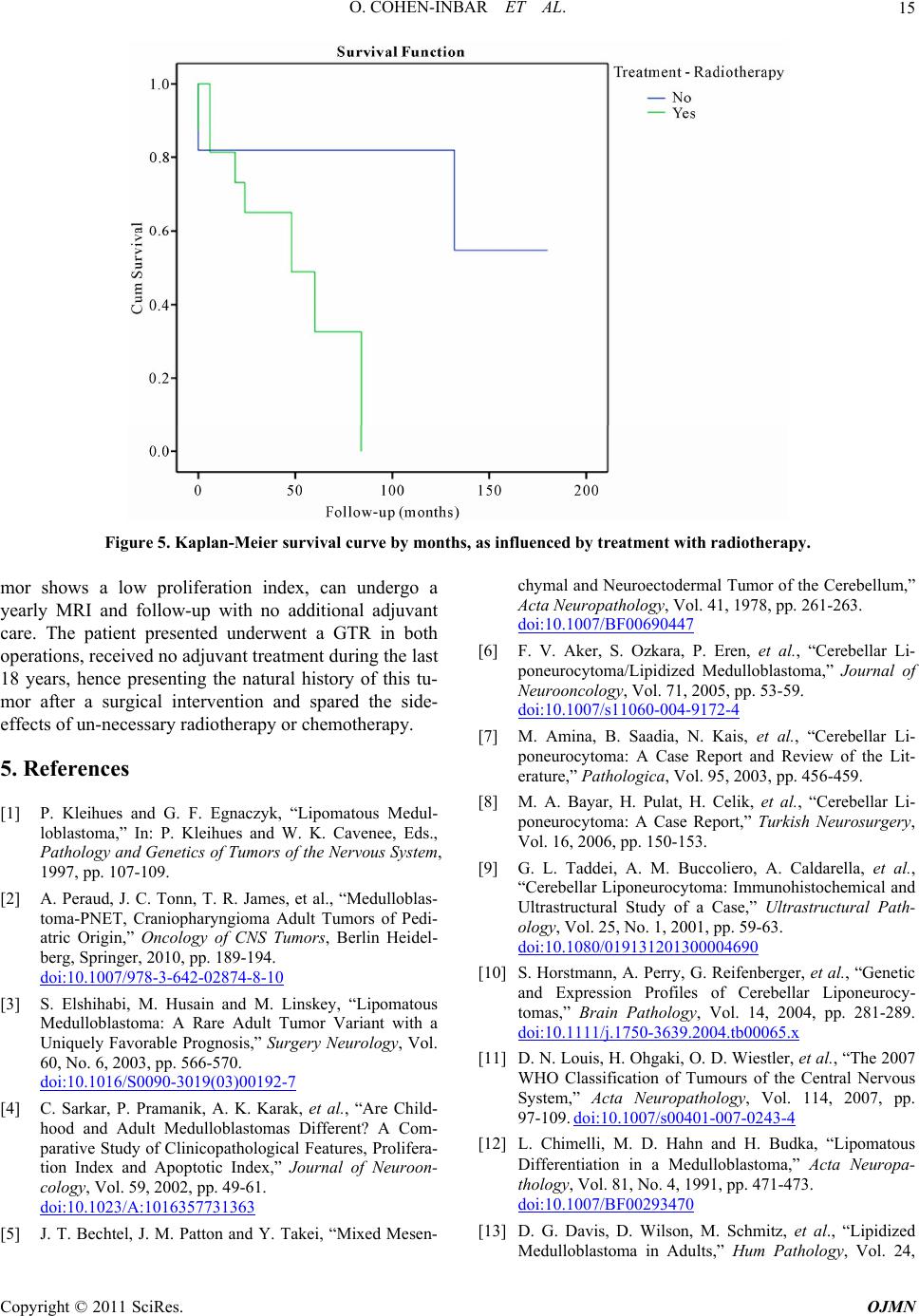

Open Journal of Mo dern Neurosurgery, 2011, 1, 10-16 doi:10.4236/ojmn.2011.12003 Published Online October 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojmn) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJMN The Natural History and Treatment Guidelines of Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma—A Case Report Or Cohen-Inbar, Euvgeni Vlodavsky, Menashe Zaaroor Department of N e urosurgery, Rambam Maimondes Health care campus, Haifa, Israel Faculty of Medicine, Technion Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel E-mail: orcoheni@tx.technion.ac.il, or _coheni@ra mbam.healt h. gov.il Received August 16, 2011; revised September 5, 2011; accepted September 20, 2011 Abstract Background and Importance: Lipomatous medulloblastoma (cerebellar liponeurocytoma) is a rare cerebellar tumor, with only twenty-nine cases reported, considered a distinct variant of medulloblastoma. The few cases described support an indolent nature for this tumor. We aim at defining the optimum treatment strategy and long-term behavior for this tumor entity. Clinical presentation: A 74 years old male presented on September 2010 complaining of mild dizziness and headache slowly progressing over a few months. This gentleman was operated on at our department some 18 years ago for a right cerebellar hemispheral lesion, defined as a liponeurocytoma. This patient received no adjuvant treatment. Current magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies disclosed a right hemispheral cerebellar mass, locally recurrent in the original surgical tumor bed. Gross total resection of the tumor was accomplished through a suboccipital craniotomy, with complete re- section of the lesion. The histopathological diagnosis was defined as cerebellar liponeurocytoma. No adju- vant therapy was given as initially, after the first operation. Currently, the patient is alive, fully alert with minimal neurological deficits, Barthel index 90, Kernofsky performance status of 90 and with no evidence of disease on neuroimaging. Conclusion: This patient portrays this tumor’s natural history after surgical inter- vention with no adjuvant treatment, being the longest reported follow-up and recurrence. This distinct variant of medulloblastoma appears to have a uniquely favorable prognosis, even without adjuvant therapy. A com- plete surgical resection with close follow-up seems both sufficient and prudent. Keywords: Natural History, Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma, Recurrence in 18 Years 1. Introduction Medulloblastoma rarely occurs in adults. Greater than 70% of medulloblastoma cases occur in children [1]. This tumor represents less than one percent of all adult primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors. Most adult medulloblastoma are located in the cerebellar hemisphere, unlike the midline/vermis location most prevalent in the pediatric patients [2]. Medulloblastoma is well known as having multiple histopathological vari- ants, including those displaying predominantly neuronal, glial, and/or myoid differentiation [3]. Sarkar et al. stated that the survival benefit in adults does not seem to be related to the histological variant (classical versus des- moplastic medulloblastoma variant), but rather to age [4]. The one exception to this statement is the lipomatous medulloblastoma variant, occurring almost exclusively in adults. The first lipomatous medulloblastoma (Cerebellar liponeurocytoma) was reported in 1978 by Bechtel et al. in a 44-year-old man [5]. Twenty-nine cases have been reported so far, under different names, such as “lipoma- tous medulloblastoma, lipidized medulloblastoma, neu- rolipocytoma, medullocytoma and lipomatous glioneu- rocytoma” [6] [Table 1]. Cerebellar liponeurocytoma has been recognized by the 2000 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the central nervous system as a distinct clinicopathologic entity. In the new classification, this tumor subset is classified in the cate- gory of glioneuronal tumors grade I or II due to its fa- vorable clinical behavior [7], even with incomplete re- section or multicentric appearance [3]. Cerebellar lipo- neurocytoma is a neuroectodermal tumor consisting of both neuronal and glial elements. Immunohistochemistry for GFAP, synaptophysin and NSE are usually positive  O. COHEN-INBAR ET AL.11 Table 1. Treatment of liponeurocytoma with radiotherapy/ death cross-tabulation. death No Yes Total No 8 3 11 Radiotherapy Yes 8 8 16 Total 16 11 27 indicating the mixed glial and neuronal elements [6,8,9]. This tumor shares several features with the cerebellar medulloblastoma, which may include an origin from the periventricular matrix of the fourth ventricle or the ex- ternal granular layer of the cerebellum. Recent work us- ing cDNA expression array data suggests a relationship to central neurocytomas [10]. Microscopically, the tumor consists of small round to ovoid cells, with an eosino- philic scanty cytoplasm, extending between interspersed regions of lipidized cells that resemble mature adipocytes. Mitoses, areas of vascular proliferation and necrosis are all rare [1,6-9,11-16]. Mitotic activity is usually absent and the growth fraction, as reflected by the MIB-1 label- ing index, is in the range of 1% ~ 3% [1, 6-8,11-16]. The radiological appearance of this tumor on com- puted tomography (CT) is characterized as a hypodense mass with intermingled areas exhibiting the attenuation values of fatty tissue. T1-weighted MR images feature this tumor as hypointense with scattered foci of hyperin- tense signal, displaying moderate contrast enhancement. T2-weighted MR images feature this tumor as slightly hyperintense relative to the cortex, with no edema pre- sent. Areas of fat density as assessed on CT scans and on MRI-T1WI help to distinguish this rare neoplasm from the more common adult medulloblastomas or ependy- momas [17]. The aim of surgery is a gross total resection (GTR) of the tumor. In most of the cases reported there was a reasonable border between the tumor and sur- rounding tissue [17-19] and gross total removal of the tumor was feasible. 2. Clinical Summery A 74 years old male presented to our institute on Sep- tember 2010 describing an indolent, subjective feeling of dizziness and headache slowly progressing over the pre- vious few months. Aside from a mild benign prostatic hyperplasia and hypercholesterolemia controlled medi- cally, he did not suffer any other chronic illnesses. This gentleman was operated on at our institute some 18 years ago, for a right cerebellar hemispheral lesion. A GTR was achieved. The histopathological specimens were sent for consultation to professor John J. Kepes, who de- scribed it as “a tumor, whose neuroectodermal origin is probably not in doubt, having cellular areas to suggest differentiating medulloblastoma, elsewhere pilocytic astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma like foci and perivascu- lar rosettes as seen in ependymomas, and striking large round spaces that I am sure were filled with fat”. It was diagnosed as a medulloblastoma with lipoid differentia- tion (termed later as a liponeurocytoma). The patient received no adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy and returned to a fully independent, working and productive life. During the next few years the patient was followed as an outpatient, but dropped out of follow-up at some point. During the years 2004 and 2005 the patient presented to the emergency room twice reporting of a mild dizziness. A non-contrast enhanced computed tomography was performed, interpreted as normal with minimal chronic changes in the tumor bed. The patient was discharged without a neurosurgical consult, and returned to be fully active. A retrospective review of these scans raises sus- picion of a local recurrence within the tumor bed, meas- uring 13 mm in its largest diameter (Figure 1). Neurological examination: Mild dysdiadochokinesis, no ataxia, a negative Romberg sign. Neuro-radiological findings: Current imaging as of September 2010 showed a non-enhancing mass within the tumor bed on tomography, measuring 43 mm in its largest diameter (Figure 2). The MRI appearance was described as a hypercellular partially cystic lesion, hav- ing delayed diffusion and a pathological enhancement. Signs of intralesional hemorrhage or calcifications were suspected and a mild peritumoral edema and multiple VRS described (Figure 3). Surgical in tervention: A right paramedian suboccipital craniotomy in the sitting position was performed. The tumor was grossly gray-reddish in color, partially at- tached to the surrounding tissue but well circumscribed. It was easily detachable from adjacent brain tissue and a GTR was achieved. The postoperative course was un- eventful with the exception of an obstructive hydro- cephalus secondary to peritumoral edema causing a nar- Figure 1. A non contrast enhanced computed tomography, 2005. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJMN  O. COHEN-INBAR ET AL. 12 Figure 2. Computed tomography findings, both enahnced and not-enhanced by contrast, 2010. (a) (b) (c) (d) Figure 3. 2010 MRI, A. axial FLAIR, B. Coronal T1 with gadolinium, C. Axial T2, D. Sagittal T2. rowing of the forth ventricle. This was managed with a ventricular drain for a few days after which the edema subsided and the hydrocephalus resolved. The patient was discharged shortly after. Pathological findings: On histopathological sections, small round to oval cells characteristic of medulloblas- toma were found in eosinophilic neuropil matrix, inter- spread with groups of lipocytes. Sections stained strongly positive for Neurontin, synaptophysin, only minimally positive for the proliferation marker Ki-67, estimated as less than 5% of the cells (Figure 4). 3. Discussion Lipomatous differentiation of central nervous system (a) (b) (c) (d) Figure 4. Microscopic and immunohistochemical features of lipomatous medulloblastoma. (a) small round and oval cells of medulloblastoma in eosinophilic neuropil matrix and the group of lipocytes; Hematoxylin and eosin, x100; (b) strongly positive immunostain for NeuN; immunoperoxi- dase, x100; (c) positive immunostaining for synaptophysin; immunoperoxidase, x100; (d) only few cells are positive for proliferation marker Ki-67, immunoperoxidase, x200. tumors is rare. Among astrocytic neoplasias, lipomatous differentiation is best known to be present in pleomor- phic xanthoastrocytoma [20]. Multivacuoler lipidization is also observed in glioblastoma multiforme, ependy- moma and primitive neuroectodermal cerebral tumors [21-24]. Cerebellar liponeurocytoma is a rare cerebellar tumor, with only 29 cases reported under many different names [Table 2]. Although the few cases described sup- port the relatively benign nature of this lesion, the opti- mum treatment strategy and long-term follow-up and prognosis still has to be defined [8]. Reviews published in the literature report a 5-year survival rate of 81% [6, 19], with recurrence appearing as late as 15 years after surgery, although most appear sooner [1,7,8-13,13-14, 25-30]. A caveat to this figure stems from the low num- ber of patients per report (most are case reports) and the inconsistency in pathological classification prior to 2000. Furthermore, since these patients were treated using dif- ferent protocols, this figure seems misleading. Some, more aggressively behaving relapsing lesions have also been described [29]. The patient described in this paper is, to the best of our knowledge, the longest follow-up reported presenting with radiographic progression at 13 years and a clinical progression at 18 years. Current day guidelines as to the treatment of adult medulloblastoma define surgical resection of the lesion as the first line treatment. According to Brandes et al., low-risk patients with no resiual disease should receive d Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJMN  O. COHEN-INBAR ET AL. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJMN 13 Table 2. Review of the literature , pre sumptive case s of liponeurocytoma: The clinical, histo-pathological and follow-up data. Immunostaining Tx. Reference No Age Sex Site Adi Tc Pi %SRT Follow-up Year Authors 1 44 M Cerebellar hemisphere - - - +- D 18 hours after surgery 1978 Bechtel et al. [5] 2 42 M Lt.Cerebellar hemisphere GFAP(+), Vim(+), S100(+) GFAP(+), NSE(+) S100(+) - +- A at 5 years 1991 Chimelli et al. [12] 3 49 F Vermis NA Syn(+), Leu-7(+), GFAP(−), NF(−)- +- A at 5 years 1993 Davis et al. [13] 4 53 M Vermis, bilateral extension NA Syn(+) ,Leu-7(+), GFAP(−), NF(−)- +54 GyD at 6 monthes 1993 Davis et al. [13] 5 50 F Cerebellar hemisphere GFAP(+) Syn(+), NSE(+), PGP-9.5(+), DES(+)F <1 +- A at 4 years 1993 Ellison et al. [27] 6 37 M Lt. Cerebellar hemisphere GFAP(+) Syn(+), NF(−), GFAP(+)F <1 +- R at 10 years, Reop. at R, D 1 year post-op. 1996 Giangaspero et al. [28] 7 36 F Lt. Cerebellar hemisphere GFAP(+) Syn(+), NF(−) GFAP(+)F, <1 +- R at 10 years, Reop, 2nd R at 5years, Reop. A. 1996 Giangaspero et al. [28] 8 57 F Vermis GFAP(+) Syn(+), NF(−), GFAP(+)F <1 +60 GyAAW after 2 years 1996 Giangaspero et al. [28] 9 48 F Rt. Cerebellar hemisphere Syn(+), NSE(+), MAB-2(+) Syn(+), GFAP(+), NSE(+), S100(+), MAP-2(+), P53(−) <1 +50 GyA at 3.5 years 1996 Söylemezoğlu et al. [15] 10 53 M Lt. CPA Syn(+), NSE(+), MAB-2(+) Syn(+), GFAP(+), S100(+),P53(−),M AP-2(+), NF(−), NSE(+), <5 +- R at 12 years, Reop., A. 1996 Söylemezoğlu et al. [15] 11 59 F Lt. CPA Syn(+), NSE(+), MAB-2(+) Syn(+), GFAP(+), S100(+), P53(−), MAP-2(+), NF(−), NSE(+), <3 +55 Gy 24 GyAAW at 5 years. 1996 Söylemezoğlu et al. [15] 12 55 M Vermis and Rt. Cerebellar hemisphere S100(+)F, Vim(+) Syn(+), S100(+), NSE(+), GFAP(+)<1+- A at 8 months 1997 Orlandi et al. [16] 13 67 F Vermis Syn(+), GFAP(+), S100(+) Syn(+), S100(+), NSE(+), GFAP(+)<1+- D post-op. 1998 Compora et al. 14 28 F Vermis D at 4 years 15 23 M Hemisphere D at 7 years 16 30 M Vermis D at post-op. 17 9 M Vermis D at 5 years 18 11 M Vermis D at 2 years 19 4 F Hemisphere Vim(+), KO-1(+), CR3/43(+) NF/MAP-2(+) 19.5~ 40.5 ++ D at post-op. 2000 Giordana et al. [14] 20 38 M Rt.hemisphere NA Syn(+), GFAP (−)low +- A at 15 months 2001 Alkadhi et al. [17] 21 66 M Lt.hemisphere NA NA 3 +36 Gy*A at 6 months 2001 Jackson et al. [19] 22 61 M Rt.hemisphere NA Syn(+), NSE(+), GFAP(+), P53(+), NF(+) F +- NA 2001 Taddei et al. [9]  O. COHEN-INBAR ET AL. 14 23 6 F Vermis Syn(+), S100(+), GFAP(-) Syn(+), S100(+) 33.3 ++ Chemotherapy tx. As well, A at 6 months 2002 Sharma et al. 24 53 F Rt. hemisphere GFAP(+), Vim(+), NSE(+)Syn(+), NSE(+) <5 ++ A at 1 year 2002 Montagna et al. 25 49 F Vermis, Intra-ventricular Syn(+) weak Syn(+), S100(+), GFAP(+), P53(−)<1 ++ D at 19 months 2003 Aker et al. [6] 26 45 F Rt. hemisphere NA GFAP(+), NSE(+), CEA(−) <2.5+3.6 Gy** Chemotherapy tx., AAW at 3 years. 2003 Elshihabi et al. [3] 27 38 F Lt. hemisphere NA NA NA+NA NA 2003 Amina et al. [7] 28 64 M Rt. hemisphere NSE(+), NF(+), GFAP(+) NSE(+), NF(+), GFAP(−) 20 +15.4 Gy R at 3.5 years, Reop. A at 5 months 2005 Buccoliero et al. [30] 29 39 M Vermis, Intra-ventricular NA NSE(+), Syn(+), GFAP(−), NFP(−)<1 +- A at 45 days 2006 Bayar et al. [8] M/F – male / female, Adi – adipocytes, Tc – Tumor cell, S – surgery, RT – radiotherapy, F - Focal, Pi – Proliferation index, D – Deceased, A – alive, AAW – alive and well, R – recurrence, NA – not available, GFAP – Glial fibrillar acid protein, NSE – neural specific enolase, Syn – synaptophysin, Vim – vimentin. CPA – cerebellopontine angle, Reop –reoperation, *36 Gy for the entire brain, 56 Gy boost to posterior fossa; **3.6 Gy to the spine and whole brain, 1,800 cGy boost dose to the posterior fossa. The patient also received chemotherapy for 12 months, consisting of cisplatin, PCNU, and vincristine. craniospinal radiation of 36 Gy and a boost to the poste- rior fossa of about 18 Gy. High-risk patients with resid- ual or metastatic disease should receive additional che- motherapy with cisplatin, etoposide, and cyclophospha- mide [2,31]. Out of the twenty-nine patient described, four pediatric patients operated on underwent a GTR. Proliferation index was >3% in all children, all received radiotherapy following different protocols, one patient received chemotherapy. Prognosis was dismal, with most children deceased during the follow-up (3 out of 4 pa- tients). Of the remaining 25 patients described, 12 re- ceived radiotherapy following the operation (described as GTR for all) following different protocols. Prolifera- tion index in this group was >3% in 7 patients (58%), as compared to 15% in those not receiving radiotherapy. Only a single recurrence is described in the irradiated group (as compared to 3 in those not receiving radio- therapy), although a significantly higher mortality rate was noted in those patients receiving radiotherapy (8 patients versus 3 in those not irradiated). This can be attributed to iatrogenic irradiation induced pathology, concurrent illnesses, a more aggressive tumor behavior or a combination of all of the above [Table 2]. Trying to construct a Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curve is some- what problematic, still supporting the same conclusions [Table 1, Figure 5]. The main weakness of the KM curve stems from the small sample size, inherent to this tumor. Of the eleven patients not receiving radiotherapy, three died during the follow-up. Of the sixteen patients irradiated, eight died during the follow-up. Incomplete data required for the KM curve construction exist for two patients [no. #22 and #27 in Table 2]. The KM curve, under the caveats mentioned, supports the argument that radiotherapy and accompanying morbidity is not proven in the liponeurocytoma patient, actually resulting in shorter survival. The indolent clinical behavior and suspected natural history of the cerebellar liponeurocytoma, manifesting as a slowly growing lesion only locally recurrent, raises doubts about the appropriateness of adjuvant radiothe- rapy and/or chemotherapy. Such an aggressive treatment approach, having a high biological toil and horrible iatrogenic side effects [8] has not been proven effective enough to our opinion, given any outcome parameter as an indicator. According to Kleihues [1], the prognosis is favorable if the MIB-1 index is in the range of 1% ~ 3% and aggressive adjuvant therapy is not mandatory. There have been no reports of spinal drop metastases in the literature and it is therefore reasonable to avoid spinal radiation [8]. In our patient, after reviewing current literature, a joint multidisciplinary staff comprising of neurosurgeons, neuro-oncologists, neuroradiologists and neuropathologists has recommended pursuing a conser- vative treatment approach with close clinical and radio- logical follow-up. 4. Conclusions The small number of patients reported with this type of lesion, limits our understanding of this tumor's natural history. Most of the information available from case re- ports indicates that this tumor has a benign biological behavior and prognosis in adults. Thus, expectant treat- ment with close follow-up seems both prudent and suffi- cient. We suggest that a patient with established liponeu- rocytoma, who underwent aGTR, and in which the tu- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJMN  O. COHEN-INBAR ET AL.15 Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier survival curve by months, as influenced by treatment with radiotherapy. mor shows a low proliferation index, can undergo a yearly MRI and follow-up with no additional adjuvant care. The patient presented underwent a GTR in both operations, received no adjuvant treatment during the last 18 years, hence presenting the natural history of this tu- mor after a surgical intervention and spared the side- effects of un-necessary radiotherapy or chemotherapy. 5. References [1] P. Kleihues and G. F. Egnaczyk, “Lipomatous Medul- loblastoma,” In: P. Kleihues and W. K. Cavenee, Eds., Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Nervous System, 1997, pp. 107-109. [2] A. Peraud, J. C. Tonn, T. R. James, et al., “Medulloblas- toma-PNET, Craniopharyngioma Adult Tumors of Pedi- atric Origin,” Oncology of CNS Tumors, Berlin Heidel- berg, Springer, 2010, pp. 189-194. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02874-8-10 [3] S. Elshihabi, M. Husain and M. Linskey, “Lipomatous Medulloblastoma: A Rare Adult Tumor Variant with a Uniquely Favorable Prognosis,” Surgery Neurology, Vol. 60, No. 6, 2003, pp. 566-570. doi:10.1016/S0090-3019(03)00192-7 [4] C. Sarkar, P. Pramanik, A. K. Karak, et al., “Are Child- hood and Adult Medulloblastomas Different? A Com- parative Study of Clinicopathological Features, Prolifera- tion Index and Apoptotic Index,” Journal of Neuroon- cology, Vol. 59, 2002, pp. 49-61. doi:10.1023/A:1016357731363 [5] J. T. Bechtel, J. M. Patton and Y. Takei, “Mixed Mesen- chymal and Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Cerebellum,” Acta Neuropathology, Vol. 41, 1978, pp. 261-263. doi:10.1007/BF00690447 [6] F. V. Aker, S. Ozkara, P. Eren, et al., “Cerebellar Li- poneurocytoma/Lipidized Medulloblastoma,” Journal of Neurooncology, Vol. 71, 2005, pp. 53-59. doi:10.1007/s11060-004-9172-4 [7] M. Amina, B. Saadia, N. Kais, et al., “Cerebellar Li- poneurocytoma: A Case Report and Review of the Lit- erature,” Pathologica, Vol. 95, 2003, pp. 456-459. [8] M. A. Bayar, H. Pulat, H. Celik, et al., “Cerebellar Li- poneurocytoma: A Case Report,” Turkish Neurosurgery, Vol. 16, 2006, pp. 150-153. [9] G. L. Taddei, A. M. Buccoliero, A. Caldarella, et al., “Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma: Immunohistochemical and Ultrastructural Study of a Case,” Ultrastructural Path- ology, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2001, pp. 59-63. doi:10.1080/019131201300004690 [10] S. Horstmann, A. Perry, G. Reifenberger, et al., “Genetic and Expression Profiles of Cerebellar Liponeurocy- tomas,” Brain Pathology, Vol. 14, 2004, pp. 281-289. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00065.x [11] D. N. Louis, H. Ohgaki, O. D. Wiestler, et al., “The 2007 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System,” Acta Neuropathology, Vol. 114, 2007, pp. 97-109. doi:10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4 [12] L. Chimelli, M. D. Hahn and H. Budka, “Lipomatous Differentiation in a Medulloblastoma,” Acta Neuropa- thology, Vol. 81, No. 4, 1991, pp. 471-473. doi:10.1007/BF00293470 [13] D. G. Davis, D. Wilson, M. Schmitz, et al., “Lipidized Medulloblastoma in Adults,” Hum Pathology, Vol. 24, Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJMN  O. COHEN-INBAR ET AL. 16 1993, pp. 990-995. doi:10.1016/0046-8177(93)90113-U [14] M. T. Giordana, P. Schiffer, A. Boghi, et al., “Medul- loblastoma with Lipidized Cells Versus Lipomatous Me- dulloblastoma,” Clinical Neuropathology, Vol. 19, 2000, pp. 273-277. [15] F. Soylemezoglu, D. Soffer, B. Onol, et al., “Lipomatous Medulloblastoma in Adults: A Distinct Clinicopathologi- cal Entity,” American Journal of Surgical Pathology, Vol. 20, 1996, pp. 413-418. doi:10.1097/00000478-199604000-00003 [16] A. Orlandi, B. Marino, M. Brunori, et al., “Lipomatous medulloblastoma,” Clinical Neuropathology, Vol. 16, 1997, pp. 175-179. [17] H. Alkadhi, M. Keller, S. Brandner, et al., “Neuroimag- ing of Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma: A Case Report,” Journal of Neurosurgery, Vol. 95, 2001, pp. 324-331. doi:10.3171/jns.2001.95.2.0324 [18] F. Cacciola, R. Conti, G. L. Taddei, et al., “Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma: A Case Report with Considerations on Prognosis and Management,” Acta Neurochirurgica, Wien, Vol. 144, 2002, pp. 829-833. doi:10.1007/s007010200082 [19] T. R. Jackson, W. F. Regine, D. Wilson, et al., “Cerebel- lar Liponeurocytoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature,” Journal of Neurosurgery, Vol. 95, 2001, pp. 700-703. doi:10.3171/jns.2001.95.4.0700 [20] J. J. Kepes, L. J. Rubinstein and L. F. Eng, “Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma: A Distinctive Meningocerebral Glio- ma of Young Subjects with Relatively Favorable Progno- sis,” Cancer, Vol. 44, 1979, pp. 1839-1852. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197911)44:5<1839::AID-CNCR 2820440543>3.0.CO;2-0 [21] J. M. Roda and M. Gutierrez-Molina, “Multiple Intraspi- nal Low-Grade Astrocytomas Mixed with Lipoma As- trolipoma: A Case Report,” Journal of Neurosurgery, Vol. 82, 1995, pp. 891-894. [22] M. M. Ruchoux, J. J. Kepes, P. Dhellemmes, et al., “Li- pomatous Differentiation in Ependymomas: A Report of Three Cases and Comparison with Similar Changes Re- ported in Other Central Nervous System Neoplasms of Neuroectodermal Origin,” American Journal of Surgical Pathology, Vol. 22, 1998, pp. 338-346. doi:10.1097/00000478-199803000-00009 [23] D. S. Russel and L. J. Rubenstein, “Tumors of Central Neuroepithelial Origin,” In: D. S. Russel and L. J. Rub- enstein, Eds., Pathology of Tumors of the Nervous System, 6th Edition, Edward Arnold, London, 1998, pp. 460-470. [24] L. Selassie, R. Rigotti, J. J. Kepes, et al., “Adipose Tissue and Smooth Muscle in a Primitive Neuroectodermal Tu- mor of Cerebrum,” Acta Neuropathology, Vol. 87, 1994, pp. 217-222. doi:10.1007/BF00296193 [25] A. Akhaddar, I. Zrara, M. Gazzaz, et al., “Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma (Lipomatous Medulloblastoma),” Jour- nal of Neuroradiology, Vol. 30, 2003, pp. 121-126. [26] C. H. Alleyne, S. Hunter, J. J. Olson, et al., “Lipomatous Glioneurocytoma of the Posterior Fossa with Divergent Differentiation: A Case Report,” Neurosurgery, Vol. 42, 1998, PP. 639-643. [27] D. W. Ellison, S. C. Zygmunt and R. O. Weller, “Neuro- cytoma/Lipoma (Neurolipocytoma) of the Cerebellum,” Neuropathol Application Neurobiology, Vol. 19, 1993, pp. 95-98. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.1993.tb00410.x [28] F. Giangaspero, G. Cenacchi, F. Roncaroli, et al., “Me- dullocytoma (Lipidized Medulloblastoma): A Cerebellar Neoplasm of Adults with Favorable Prognosis,” Ameri- can Journal of Surgical Pathology, Vol. 20, 1996, pp. 656-664. doi:10.1097/00000478-199606000-00002 [29] M. D. Jenkinson, J. J. Bosma, P. D. Du, et al., “Cerebel- lar Liponeurocytoma with an Unusually Aggressive Clinical Course: A Case Report,” Neurosurgery, Vol. 53, 2003, pp. 1425-1427. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000093430.61239.7E [30] A. M. Buccoliero, A. Caldarella, S. Bacci, et al., “Cere- bellar Liponeurocytoma: Morphological, Immunohisto- chemical, and Ultrastructural Study of a Relapsed Case,” Neuropathology, Vol. 25, 2005, pp. 77-83. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1789.2004.00574.x [31] A. A. Brandes, M. Ermani, P. Amista, et al., “The Treat- ment of Adults with Medulloblastoma: A Prospective Study,” International Journal of Radiation Oncology Bi- ology Physics, Vol. 57, No. 3, 2003, pp. 755-761. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00643-6 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJMN

|