Journal of Software Engineering and Applications

Vol.7 No.5(2014), Article ID:46054,9 pages DOI:10.4236/jsea.2014.75038

A Survey of Concepts Location Enhancement for Program Comprehension and Maintenance

Nouh Alhindawi1, Jamal Alsakran2, Ali Rodan2, Hossam Faris2

1Faculty of Sciences and Information Technology, Jadara University, Irbid, Jordan

2King Abdullah II School for Information Technology, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

Email: hindawi@jadara.edu.jo, j.alsakran@ju.edu.jo, a.rodan@ju.edu.jo, hossam.faris@ju.edu.jo

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 9 April 2014; revised 3 May 2014; accepted 11 May 2014

ABSTRACT

When correcting a fault, adding a new concept or feature, or adapting a system to conform to a new platform, software engineers must first find the relevant parts of the code that correspond to a particular change. This is termed as concept or feature location process. Several techniques have been introduced which automate some or all of the process of concept location. Those techniques rely heavily on code comprehension as it is considered a prerequisite when attempting to maintain any software system. It provides a comprehensive overview of large body work which is beneficial to researchers and practitioners. This paper presents an overview of code comprehension categorization and consequence. A systematic literature survey of concept location enhancement techniques is also presented. Moreover, the paper presents an overview of the role of concept location in program comprehension and maintenance and discusses information retrieval techniques to advance concept location.

Keywords:Concept Location, Feature Location, Program Comprehension, Software Maintenance, Evolution, Information Retrieval

1. Introduction

Software maintenance is a very costly, broad, and complicated problem as it requires very deep understanding of the target system source code. Therefore, professional developers must be familiar with the system undergoing changes in order to accomplish the required maintenance tasks. The process of expressing the behavior, organization, components relationship, and architecture of the software that are not explained in the documentation requires great effort to be complete and precise. Moreover, while exploring and searching the source code, the developers must take into account both the structural characteristics of the source code and the nature of the problem domain, such as, internal comments, external documentations, variable names, and annotations. This constitutes the problem of program comprehension [1] -[3] .

Comprehension activities constitute a major portion of modern software project maintenance and evolution efforts and requires roughly 40 percent of the whole cost of any software project [4] . Other estimates show that programmers spend more than half of their time in exploring and reading the source code when adding new features or concepts to a system [5] [6] .

Concept location is identified in the literature as identification or concern location. Features are special concepts that are associated with the user observable functionality of the system [3] [7] . The common goal of concept location techniques is to recognize the source code fragments that implement a concept of interest from the problem or solution domain of the software. Concept location is an essential part of the software change process [7] .

The research field of program comprehension and concept location is characterized as rich, containing various and mixed topics, which coupled with changes in models and research environment in the last few decades. In this paper, we present a survey of the techniques and advances in concept location for program comprehension. The work presented here has two main contributions. The first is a discussion of program comprehension techniques, relevant studies, and categorization. The second is a systematic survey of concept location techniques and categorization. A detailed discussion of using information retrieval techniques to facilitate concept location is also presented.

2. Historical Perspective for Program Comprehension

In software engineering, program comprehension is constantly taken into consideration, and it poses as a serious concern for the developers [3] . When new programmers are assigned to an old code, they often complain about understanding it, and express their views about the code being unintelligible; therefore, software comprehension is very crucial and is especially needed in the occasions when old seasoned programmers leave their projects. That is, the absence of the original programmers slows down the understanding of the software, and thus negatively impacts comprehension [5] .

Unfortunately, the usual case is that the programmers who originally developed the system are no longer available to assist, or sometimes parts of the software may be certified from a third party that monitors the maintenance process. In both situations, the developers who are designated for maintaining the system must understand it [8] [9] . In other words, it is of an absolute necessity that every associate on the maintenance team develop a comprehensive understanding of the software [10] .

In general, the purpose of comprehension is mainly dependent on the task of interest. That is to say, there must be some cause to force the development team to comprehend software artifacts. For example, a developer may try to localize a bug/feature, or assess possible or obtainable changes to an Application Program Interface (API). Most frequently, a specific concept or particular feature is inspected in the software, and this concept or feature is most often related to a user change request [11] . Program comprehension is one of the most important steps in addressing many software engineering and maintenance tasks. It is extremely crucial for correctly gathering knowledge about the program at hand [12] [13] . This knowledge is usually diverse, meaning that several aspects are integrated into it like maintenance [14] [15] , documentation [16] , debugging [17] [18] , reuse [19] [20] , and verification [21] [22] .

The field of program comprehension is up to date with respect to supporting tools that are either new or adapted to address program comprehension requirements for new software development and maintenance tasks [23] . Storey reviews some of the key cognitive theories of program comprehension that have appeared over the past three decades, and he explores how the tools that are generally used at the present are developed and updated to improve and support program comprehension tasks [8] . In [8] [24] , the authors introduce user studies to discover how, and how well, different program comprehending tools, in fact, assist programmers in understanding the software artifacts. In [2] , the authors present a work that advocates the examination of better measures and controlled experiments to assess the effectiveness of program comprehension techniques.

Software comprehension tools aid engineers in capturing the benefit of new added code. They are necessary as economic demands require a maintenance engineer to rapidly and successfully develop comprehension of the parts of source code that are relevant to a maintenance request. In general, the tools make program comprehension more effective [6] . In [23] , the authors conclude that any program comprehension tool has to be proven to generate benefits throughout maintenance tasks. There have been some usability experiments relevant to evaluating program comprehension tools [8] . Bellay and Gall conduct a comparative evaluation of five reverse engineering tools using a case study and an evaluation framework [2] . They conclude that the performance and capabilities of are verse engineering tool are dependent on the application domain as well as the analysis purpose.

Comprehension Process Categorization

In program comprehension, we must be precise about why we are trying to comprehend (i.e., task), what we are trying to comprehend (i.e., object), and who is trying to comprehend (i.e., subject). The entity of comprehension may be as small as a single function or as large as the whole software system.

Typically, the study of program comprehension can be characterized by two instruments, which are the theories and the tools available in this regard. The theories gain their importance in the sense that they supply a rich clarification about how developers understand any system software. In addition to the theories, there are the tools that are utilized to support and help in comprehension activities [8] .

The comprehension process can be categorized into two basic styles; the first being top-down comprehension, while the second is bottom-up comprehension. For top-down comprehension, Brooks [9] hypothesizes that developers usually understand a completed program in a top-down fashion by restructuring facts about the area, topics, and objectives of the program, and linking those facts to the system source code. Soloway and Ehrlich [14] examine the style of top-down comprehension, and conclude that this style is used when the code or type of code is recognizable.

The second category is bottom-up comprehension which supposes that developers initially read the software code lines, and then make an effort to group them into an advanced level of abstraction [13] . Subsequently, the new levels are combined incrementally until the developers come to acquire a deep understanding of the intended software program. Pennington also describes the bottom-up model and concludes that at the beginning of the comprehension process, developers build up an abstraction for control flow of the program; this abstraction contains the order and the sequence of the most important operations in the program [25] .

3. Concept Location Motivations

Understanding a software system is a prerequisite before making any changes to that system. It requires the developer to gather the scattered information across the software systems source code, and then present the extracted information in a readable and understandable view. This task is time consuming and error prone, especially when the system is large and complex. Quite a lot of research has been done investigating ways to decrease the time and effort needed to understand a system. Moreover, software consists of huge number of artifacts; some of them are planned to be read by the compiler, although many others are intended to be understood by the developers.

In the last decade, researchers have proposed techniques that help in gathering the most important scattered information and presenting it in a good manner that helps in understanding the intended system [3] [26] [27] .

When adding a new concept or modifying existing features in a system, programmers must identify which parts of source code are most relevant to the intended concept. Identifying these relevant parts in the context of software engineering is called concept location, which is also considered as a part of the incremental change procedure. A feature is defined as a human-oriented expression of the computational objective [7] [26] [28] - [30] . So, we can say that a feature is a concept that is coupled to executions with some predefined input.

3.1. Historical Perspective for Concept Location

Historically, developers used pattern matching techniques like grep to locate the concept or features in the source code. Using pattern-matching techniques is simple; it performs searching through pattern matching on character strings. Nevertheless, it requires a lot of experience from the developers. If the technique fails, more advanced tools are required, especially when the system is large [6] [7] [28] [31] .

Biggerstaff et al. [32] refer to concept location as the concept location assignment problem. Their work is a preliminary point for a lot of efforts to facilitate and develop the process of concept location. Call graphs and program clustering graphs are used in their approach. Chen and Rajlich [33] present an approach based on looking through an Abstract System Dependencies Graph (ASDG). The ASDG can lead, guide, and help the users in the process of searching for a particular concept or feature.

Wilde [30] develops the software-reconnaissance method which utilizes dynamic information to locate concept or features in existing systems. Wong et al. [34] analyze the execution slices of test cases to the same end. Eisenbarth et al. [35] use dynamic information gathered from scenarios of invoking features in a system to locate the concept or features in source code. Poshyvanyk et al. [31] , in order to improve the accuracy of concept location process, propose a technique that combines information from an execution trace and from the comments and identifiers in the source code. M. Revelle et al. [36] apply advanced web mining algorithms Hyperlinked-Induced Topic Search (HITS) and Page Rank to analyze execution information during feature location. Their approach improves the effectiveness of existing approaches by as much as 62%.

Generally, a variety of approaches for facilitating the process of concept location process are available. Here, we mention three main approaches the developers use. The first one is the static, lexical and syntactic analysis— this approach focuses on the source code itself and its representations [5] [6] [11] . The second approach is by using graphing methods—there are a variety of graphing approaches that have been employed and developed for enhancing the process of concept location. These include, in increasing order of complexity and richness: graphing the control flow of the program [37] -[40] , the data flow of the program [37] -[40] , and program dependence graphs [38] . The third one is achieved by execution and testing of the source code or by using scenarios [29] . A survey of feature location techniques is presented in [28] .

3.2. Static and Dynamic Analysis in Concept Location

Generally, the tools that deal with feature and concept location problem are mainly classified into two categories, based on the way that such tools extract information from the source code; static and dynamic. Static approaches collect their input without execution of the intended program, while in dynamic approaches the input comes from investigating the execution traces or executing test cases [28] [39] . Neither category is optimal. The overlap between concepts or features cannot be distinguished in dynamic analysis, while static analysis often does not identify units contributing to a particular execution scenario [5] [28] .

Dynamic analysis and static analysis can be combined in different ways for concept location. One way to combine them is to use dynamic analysis to filter the program elements for static analysis instead of ranking all the program elements in a software system. Also, both analyses can rank program elements by their relevance to a feature, so another direction is to combine the rankings produced by the two techniques [7] [40] -[42] . Both of dynamic and static methods are used as input for hybrid approaches [39] . Revelle and Poshyvanyk [43] present an investigative study of ten concept and feature location techniques that use different combinations of dynamic and static analyses. In [44] , presents and discusses the applications of text retrieval to support concept location, in the context of software change.

On the other side, both static and dynamic methods often suffer from the same types of problems [28] [35] (e.g. too many false positives) or require very accurate test cases for the concept or feature, which may not be available.

3.3. Concept Location Enhancement Using Information Retrieval

Over the past ten years Information Retrieval (IR) approaches have been used to help address the problem of concept location [1] [7] [28] [31] [45] -[49] . These approaches treat the identifiers and comments within the source code as a corpus and then advanced methods are used for indexing and searching within the corpus. The documents sought here are typically methods or functions within the system. The identifiers and comments in the source code represent what is called semi-structured static information [7] [31] . This information when examined and analyzed is very valuable for maintaining software systems.

Generally, in software engineering, IR methods had been used early in the context of indexing reusable software components and automatically constructing libraries [50] . Nonetheless, in recent times, IR methods have been used in solving the problems of software maintenance and development tasks such as traceability link recovery [51] , feature and concept location [29] [31] [42] [52] , and source code clustering and summarization [53] [54] . Poshyvanyk and Marcus [42] employ these methods in the assignment of bug’s fixing based on concept problem explanation reports. Wilde et al. [39] use IR methods to recommend an ordered list of professional developers to help in the completion and implementation of software concepts change (e.g., bug reports and feature requests).

Thus, using IR techniques to leverage this information assists the developers in maintenance tasks such as concept or feature location [6] [7] [28] [40] [48] , and supports design of incremental changes to the software [26] . Vector Space Model (VSM) [28] [55] , Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) [7] , and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) [56] -[58] are examples of IR techniques that have been successfully applied in the context of concept location [5] [7] [28] [31] .

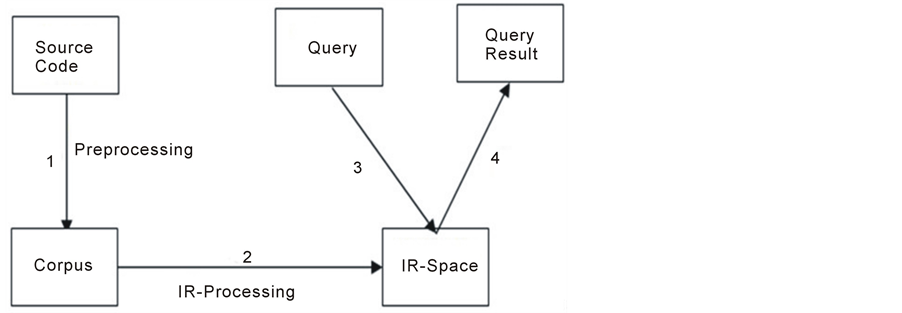

Figure 1 shows the main steps for concept location using IR. Numbers in the figure correspond to the following steps 1) creating a corpus of a software system, 2) preprocessing and indexing, 3) formulating a query, 4) ranking documents and examining results.

Constructing the corpus is an important step for concept location using Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) [7] . Five actions are taken to create the corpus: 1) extraction of identifiers, and comments; 2) extraction of method stereotypes; 3) identifiers (or terms) separations; 4) removing stop words; 5) division into documents.

The next step is to index the corpus using the employed IR method. After creating the IR-space using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) [59] , each document di in system S will have a corresponding vector vi. Reduction of dimensionality is done in this step to reflect the most important latent aspects of the corpus [7] .

Measuring the similarities between any two documents sim(di, dj), can be done by measuring the similarities between their correspondents vectors. Here cosine similarities are used. By studying and analyzing these similarities we can identify the semantic information regarding source code fragments and the relations connecting them.

In the third step, the user formulates a query by using a natural language to describe a change request in the same manner as in [31] . A user query q is converted into a document of IR-space dq and a vector vq for it is constructed. Based on the similarity measure between vq and all documents in the corpus, the most relevant documents to vq are retrieved as a ranked list {d1, d2,…, dn}.

Finally, and once the IR technique retrieves the relevant documents ranked by their similarities to the user query, then the user has the task of inspecting and investigating these documents to decide which of them are actually relevant to the query. The first ranked document d1 will be investigated first and then d2 and so on. The user decides when to stop investigating. If the user discovers a part of the feature, then the intended concept is located successfully. Otherwise, the user can reformulate the query taking into account these results.

In [60] , the authors study how additional information can be leveraged to improve the final results. Others have used similar approaches based on ontological information [61] and infer semantics from term distribution [62] . From an information theoretic standpoint the addition of relevant information will improve the results of an IR technique [63] [64] . That is, more information is better, as long as you do not add noise.

It is very costly to build knowledge base for parsing approaches to extract semantic information from source code and related documentation. Using IR methods to extract these kinds of information has been proved to be efficient, with the capacity to produce fine quality and low cost outcomes [7] . Moreover, in software programming, meaningful identifier names are generally selected by programmers. Furthermore, by using the com-

Figure 1. Concept location process using IR.

ments, the ideal programmer always describes the source code with useful and meaningful information. Thus, source code contains important and significant domain knowledge that can be extracted and expressed [7] [40] [65] . IR techniques have proven their effectiveness in expressing and discovering these types of information.

Marcus and Maletic [40] and Maletic and Valluri [66] are the first researchers to investigate LSI’s potential use in concept and feature location. They utilize similarity measures between source code components in order to cluster and classify these components. Afterwards, Maletic and Marcus continue their work in [3] to define a number of metrics for comprehension. These metrics use the profile produced by the application of LSI to the matrix of the source code. Marcus et al. [7] improve linking LSI to concept location problem, where LSI was used to map the concepts that are expressed in natural language change requests to relevant components in the source code. Poshyvanyk et al. [67] propose a Visual Studio plug-in (IRiSS), based on an existing “find” concept that uses LSI to search projects using natural language queries.

Many efforts have been made to improve the use of IR in feature location by adding or integrating meaningful information to the whole process of feature location [29] [68] . For example, in [31] , the authors combine LSI with user-execution scenarios to improve the accuracy of feature location.

While IR approaches have shown to be useful there is room to improve the accuracy of these methods. Software and comments are not natural languages. So any mapping from natural language queries to source code will typically be imperfect [60] . For more details on information-retrieval applications in software maintenance and evolution, readers are referred to the survey by Binkley and Lawrie [6] .

4. Conclusion

Software comprehension is a crucial phase during software evolution and maintenance; there are lots of techniques in this area that can be applied to deal with it. The presented paper introduces a well structured survey of concept location enhancement techniques, and its importance with respect to program comprehension along with classification for concept location techniques into static, dynamic, and hybrid. Concept location process using information retrieval approaches is also presented. Moreover, we discuss state of the art program comprehension approaches and their classification into top-down and bottom-up. A discussion about the applications of text retrieval to support concept location, in the context of software change is also presented. As a conclusion, while information retrieval and the literature approaches have shown to be useful, there is room to improve the accuracy of methods that deal with concept location enhancement.

References

- Cleary, B., Exton, C., Buckley, J. and English, M. (2009) An Empirical Analysis of Information Retrieval Based Concept Location Techniques in Software Comprehension. Empirical Software Engineering, 14, 93-130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10664-008-9095-3

- Maletic, J.I. and Kagdi, H. (2008) Expressiveness and Effectiveness of Program Comprehension: Thoughts on Future Research Directions. Frontiers of Software Maintenance (FoSM), Beijing, 28 September-4 October 2008, 31-37.

- Maletic, J.I. and Marcus, A. (2001) Supporting Program Comprehension Using Semantic and Structural Information. 23rd International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Toronto, 12-19 May 2001,103-112.

- Turver, R.J. and Munro, M. (1994) An Early Impact Analysis Technique for Software Maintenance. Journal of Software Maintenance: Research and Practice, 6, 35-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smr.4360060104

- Binkley, D. and Lawrie, D. (2010) Information Retrieval Applications in Software Development. In: Laplante, P., Ed., Encyclopedia of Software Engineering, Taylor & Francis LLC, London, 231-242.

- Binkley, D. and Lawrie, D. (2010) Information Retrieval Applications in Software Maintenance and Evolution. In: Laplante, P., Ed., Encyclopedia of Software Engineering, Taylor & Francis LLC, London, 454-463..

- Marcus, A., Sergeyev, A., Rajlich, V. and Maletic, J.I. (2004) An Information Retrieval Approach to Concept Location in Source Code. 11th Working Conference on Reverse Engineering, IEEE Computer Society, Delft, 8-12 November 2004, 214-223.

- Storey, M. (2005) Theories, Methods and Tools in Program Comprehension: Past, Present and Future. 13th International Workshop on Program Comprehension (IWPC), St. Louis, 15-16 May 2005, 181-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/WPC.2005.38

- Brooks, R. (1983) Towards a Theory of the Comprehension of Computer Programs. International Journal of Man- Machine Studies, 18, 543-554. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7373(83)80031-5

- Toffolon, C. and Dakhli, S. (2008) An Iterative Meta-Lifecycle for Software Development, Evolution and Maintenance. 3rd International Conference on Software Engineering Advances (ICSEA), 15-16 May 2005, 181-191.

- Kagdi, H., Collard, M.L. and Maletic, J.I. (2007) A Survey and Taxonomy of Approaches for Mining Software Repositories in the Context of Software Evolution. Software Maintainance and Evolution, 19, 77-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smr.344

- Rist, R. (1986) Plans in Programming: Definition, Demonstration, and Development. First Workshop on Empirical Studies of Programmers on Empirical Studies of Programmers, Ablex Publishing Corp., Washington, D.C., 28-47.

- Shneiderman, B. and Mayer, R. (1979) Syntactic/Semantic Interactions in Programmer Behavior: A Model and Experimental Results. International Journal of Computer & Information Sciences, 8, 219-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00977789

- Littman, D.C., Pinto, J., Letovsky, S. and Soloway E. (1986) Mental Models and Software Maintenance. First Workshop on Empirical Studies of Programmers on Empirical Studies of Programmers, Ablex Publishing Corp., Washington, D.C., 80-98.

- Mayrhauser, A.V. and Vans, A.M. (1997) Program Understanding Behavior during Debugging of Large Scale Software. 7th Workshop on Empirical Studies of Programmers, ACM, Alexandria, 157-179.

- Etzkorn, L.H., L.L. Bowen and Davis, C.G. (1999) An Approach to Program Understanding by Natural Language Understanding. Natural Language Engineering, 5, 219-236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1351324999002120

- Hartman, J.E. (1991) Automatic Control Understanding for Natural Programs. University of Texas at Austin, Austin.

- von Mayrhauser, A. and Vans, A.M. (1994) Program Understanding—A Survey. Department of Computer Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, 32.

- Biggerstaff, T. and Richter, C. (1987) Reusability Framework, Assessment, and Directions. IEEE Software, 4, 41-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/MS.1987.230095

- Kim, Y. and Stohr, E.A. (1998) Software Reuse: Survey and Research Directions. Journal of Management Information Systems, 14, 113-147.

- Canfora, G., Cimitile, A. and Munro, M. (1993) A Reverse Engineering Method for Identifying Reusable Abstract Data Types. Proceedings of Working Conference on Reverse Engineering, Baltimore, 21-23 May 1993, 73-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/WCRE.1993.287777

- Choi, S.C. and Scacchi, W. (1990) Extracting and Restructuring the Design of Large Systems. IEEE Software, 7, 66-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/52.43051

- Penta, M.D., Stirewalt, R.E.K. and Kraemer, E. (2007) Designing Your Next Empirical Study on Program Comprehension. 15th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC), Banff, 26-29 June 2007, 281-285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICPC.2007.17

- Storey, M.-A.D., Wong, K. and Muller, H.A. (1997) How Do Program Understanding Tools Affect How Programmers Understand Programs. Proceedings of the 4th IEEE Working Conference on Reverse Engineering (WCRE), Amsterdam, 6-8 October 1997, 12-21.

- Pennington, N. (1987) Stimulus Structures and Mental Representations in Expert Comprehension of Computer Programs. Cognitive Psychology, 19, 295-341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(87)90007-7

- Poshyvanyk, D. (2009) Using Information Retrieval to Support Software Maintenance Tasks. IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance, Edmonton, 20-26 September 2009, 453-456.

- Salton, G. and McGill, M.J. (1983) Introduction to Modern Information Retrieval. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Dit, B., Revelle, M., Gethers, M. and Poshyvanyk, D. (2011) Feature Location in Source Code: A Taxonomy and Survey. Journal of Software Maintenance and Evolution: Research and Practice, 25, 53-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smr.567

- Liu, D.P., Marcus, A., Poshyvanyk, D. and Rajlich, V. (2007) Feature Location via Information Retrieval Based Filtering of a Single Scenario Execution Trace. Proceedings of the 22nd IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering, Atlanta, 5-9 November 2007, 234-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1321631.1321667

- Wilde, N. and Scully, M.C. (1995) Software Reconnaissance: Mapping Program Features to Code. Journal of Software Maintenance, 7, 49-62.

- Poshyvanyk, D., Gueheneuc, Y.-G., Marcus, A., Antoniol, G. and Rajlich, V. (2007) Feature Location Using Probabilistic Ranking of Methods Based on Execution Scenarios and Information Retrieval. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 33, 420-432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2007.1016

- Biggerstaff, T.J., Mitbander, B.G. and Webster, D.E. (1994) Program Understanding and the Concept Assignment Problem. Communications of the ACM, 37, 72-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/175290.175300

- Chen, K.R. and Rajlich, V. (2000) Case Study of Feature Location Using Dependence Graph. Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Program Comprehension, Limerick, 10-11 June 2000, 241-247.

- Wong, W.E., Gokhale, S.S. and Horgan, J.R. (2000) Quantifying the Closeness between Program Components and Features. Journal of Systems and Software, 54, 87-98.

- Eisenbarth, T., Koschke, R. and Simon, D. (2003) Locating Features in Source Code. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 29, 210-224.

- Revelle, M., Dit, B. and Poshyvanyk, D. (2010) Using Data Fusion and Web Mining to Support Feature Location in Software. Proceedings of the 18th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension, Braga, 30 June-2 July 2010, 14-23.

- ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems (TOPLAS), ACM.

- Ferrante, J., Ottenstein, K.J. and Warren, J.D. (1987) The Program Dependence Graph and Its Use in Optimization. ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 9, 319-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/24039.24041

- Wilde, N., Gomez, J.A. Gust, T. and Strasburg, D. (1992) Locating User Functionality in Old Code. Conference on Software Maintenance, Orlando, 9-12 November 1992, 200-205.

- Maletic, J.I. and Marcus, A. (2000) Using Latent Semantic Analysis to Identify Similarities in Source Code to Support Program Understanding. 12th IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Vanvouver, 13-15 November 2000, 46-53.

- Marcus, A. and Poshyvanyk, D. (2005) The Conceptual Cohesion of Classes. Proceedings of 21st IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance (ICSM), Budapest, 26-29 September 2005, 133-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICSM.2005.89

- Poshyvanyk, D. and Marcus, A. (2007) Combining Formal Concept Analysis with Information Retrieval for Concept Location in Source Code. 15th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC), Banff, 26-29 June 2007, 37-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICPC.2007.13

- Revelle, M. and Poshyvanyk, D. (2009) An Exploratory Study on Assessing Feature Location Techniques. 17th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC), Vancouver, 17-19 May 2009, 218-222.

- Marcus, A. and Haiduc, S. (2013) Text Retrieval Approaches for Concept Location in Source Code. In: Lucia, A. and Ferrucci, F., Eds., Software Engineering, 7171, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 126-158.

- Hill, E., Pollock, L. and Vijay-Shanker, K. (2011) Improving Source Code Search with Natural Language Phrasal Representations of Method Signatures. 26th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering, Lawrence, 6-10 November 2011, 524-527.

- Pollock, L., Vijay-Shanker, K., Shep, D., Hill, E., Fry, Z.P. and Maloor, K. (2007) Introducing Natural Language Program Analysis. 7th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGSOFT Workshop on Program Analysis for Software Tools and Engineering, San Diego, 13-14 June 2007, 15-16.

- Poshyvanyk, D., Gethers, M. and Marcus, A. (2013) Concept Location Using Formal Concept Analysis and Information Retrieval. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology (TOSEM), 21, 1-34.

- McMillan, C., Grechanik, M., Poshyvanyk, D., Xie, Q. and Chen, F. (2011) Portfolio: Finding Relevant Functions and Their Usage. 33rd International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), Honolulu, 21-28 May 2011, 111-120.

- Poshyvanyk, D., Marcus, A., Ferenc, R. and Gyimóthy, T. (2009) Using Information Retrieval Based Coupling Measures for Impact Analysis. Empirical Software Engineering, 14, 5-32.

- Maarek, Y.S., Berry, D.M. and Kaiser, G.E. (1991) An Information Retrieval Approach for Automatically Constructing Software Libraries. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 17, 800-813. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/32.83915

- Marcus, A. and Maletic, J.I. (2003) Recovering Documentation-to-Source-Code Traceability Links Using Latent Semantic Indexing. 25th International Conference on Software Engineering, Portland, 3-10 May 2003, 125-135.

- Poshyvanyk, D., Gueheneuc, Y.-G., Marcus, A., Antoniol, G. and Rajlich, V. (2006) Combining Probabilistic Ranking and Latent Semantic Indexing for Feature Identification. 14th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC), Athens, 14-16 June 2006, 137-148.

- Savage, T., Dit, B., Gethers, M. and Poshyvanyk, D. (2010) TopicXP: Exploring Topics in Source Code Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation. 2010 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance (ICSM), Timisoara, 12-18 September 2010, 1-6.

- Haiduc, S., Aponte, J., Moreno, L. and Marcus, A. (2010) On the Use of Automated Text Summarization Techniques for Summarizing Source Code. 17th Working Conference on Reverse Engineering (WCRE), Beverly, 13-16 October 2010, 35-44.

- Salton, G., Wong, A. and Yang, C.S. (1975) A Vector Space Model for Automatic Indexing. Communications of the ACM, 18, 613-620. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/361219.361220

- Blei, D.M., Ng, A.Y. and Jordan, M.I. (2003) Latent Dirichlet Allocation. The Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993-1022.

- Linstead, E., Lopes, C. and Baldi, P. (2008) An Application of Latent Dirichlet Allocation to Analyzing Software Evolution. 7th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications, San Diego, 11-13 December 2008, 813- 818.

- Tian, K., Revelle, M. and Poshyvanyk, D. (2009) Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation for Automatic Categorization of Software. 6th IEEE International Working Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), Vancouver, 16-17 May 2009, 163-166.

- Anderson, E., Bai, Z., Bischof, C., Blackford, L.S., Demmel, J., Dongarra, J., Du Croz, J., Greenbaum, A., Hammarling, S., McKenney, A. and Sorensen, D. (1999) LAPACK Users’ Guide. 3rd Edition, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/1.9780898719604

- Alhindawi, N., Dragan, N., Collard, M.L. and Maletic, J.I. (2013) Improving Feature Location by Enhancing Source Code with Stereotypes. 29th IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance (ICSM), Eindhoven, 22-28 September 2013, 300-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICSM.2013.41

- Müller, H.-M., Kenny, E.E. and Sternberg, P.W. (2004) Textpresso: An Ontology-Based Information Retrieval and Extraction System for Biological Literature. PLoS Biology, 2, e309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0020309

- Teevan, J. (2001) Improving Information Retrieval with Textual Analysis: Bayesian Models and Beyond. Master’s Thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

- Binkley, D. and Lawrie, D. (2003) Information Retrieval and the Philosophy of Language. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 37, 3-50.

- Huibers, Th.W.Ch., Lalmas, M. and van Rijsbergen, C.J. (1996) Information Retrieval and Situation Theory. SIGIR Forum, 30, 11-25.

- Maletic, J.I. and Marcus, A. (2000) Support for Software Maintenance Using Latent Semantic Analysis. 4th Annual IASTED International Conference on Software Engineering and Applications (SEA), Las Vegas.

- Maletic, J.I. and Valluri, N. (1999) Automatic Software Clustering via Latent Semantic Analysis. 14th IEEE International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), Cocoa Beach, October 1999, 251-254.

- Denys, P., Andrian, M., et al. (2005) IRiSS—A Source Code Exploration Tool. Proceedings of the 21st IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance (ICSM), Budapest, 26-29 September 2005, 69-72.

- Poshyvanyk, D. and Marcus, A. (2007) Combining Formal Concept Analysis with Information Retrieval for Concept Location in Source Code. 15th IEEE International Conference on Program Comprehension (ICPC), Banff, 26-29 June 2007, 37-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICPC.2007.13