Journal of Geographic Information System

Vol.4 No.2(2012), Article ID:18766,6 pages DOI:10.4236/jgis.2012.42018

Drone Bombings in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas: Public Remote Sensing Applications for Security Monitoring

1Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, USA

2Department of Political Science, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, USA

Email: tg@geog.ucla.edu

Received December 15, 2011; revised January 20, 2012; accepted February 5, 2012

Keywords: Drones; Miram Shah; Quickbird; Remote Sensing; US War on Terrorism

ABSTRACT

Drone bombing, as a US defense strategy in Pakistan, began under the George W. Bush administration as part of the “US War on Terrorism” and has accelerated under the Obama administration. The United States government has not confirmed the use of drones in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan. We identify the region within the Federally Administered Tribal Areas with the highest incidence of drone bombing activity and use QuickBird imagery to identify evidence of drone bombing damage. The city of Miram Shah in North Waziristan had the highest incidence of drone bombings before January 1, 2010. A systematic research in 1 km2 grids over the city of Miram Shah revealed potential damage of a drone bombing at one site, recent damage at one site, and an image of a drone over the landscape. Results suggest that drone bombings are very accurate and drone missions are common in the region. It is possible for the public to monitor drone bombings and other quality of life indicators in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. The use of drones to monitor and attack enemy locations will most likely expand in the future.

1. Introduction

Drone bombing, as a US defense strategy in Pakistan, began under the George W. Bush administration as part of the “US War on Terrorism” and aimed to defeat Taliban and al-Qaeda militants who have sought refuge in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of North West Pakistan [1]. The strikes, which have continued under the Obama administration, are carried out by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and are primarily operated remotely from Creech Air Force Base in Nevada. Since 2001, Taliban and al-Qaeda activity has increased significantly in the region, triggering US security concerns [2]. The FATA has become a safe haven for the Taliban, prompting US security officials to reassess their Middle East policy. The Taliban, if left unchecked, could disrupt the progress that the US has made in neighboring Afghanistan. Currently, it is difficult to collect field data from the FATA and most of what is known about the distribution and densities of drone bombings is from second hand sources [1,3] on the locations of bombings, extent of damage, and impacts in the region that would be of use for the political science community in assessing the current impacts of drone bombings.

There has been an increasing interest in near real-time satellite imagery that can be used to assess contemporary political geography questions [4,5]. One of the current advantages of using remote sensing in political geography is that it can collect imagery of the Earth in regions where it is very difficult to collect field data [6]. For instance, it is now possible to study genocide in Darfur by quantifying the number of destroyed structures in villages in southern Sudan with high-resolution commercial imagery [7]. Currently, there are a number of commercial satellites that can provide sub-meter resolution imagery (QuickBird, IKONOS, OrbView, GeoEye) from space. This has allowed researchers to address questions that previously were impractical to study from space or on the ground.

This research examines the utility of satellite imagery to identify the location and extent of damage from drone bombings in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. First, we identify the regions with the highest incidence and density of drone bombing activity. Second, we systematically search the area to see if there is any evidence of bombing damage and determine the exact locations of US military air strikes. Finally, we assess the potential for satellite imagery to monitor the region in order to increase transparency and security in the region.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

The Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan are home to attacks carried out by the US military in an attempt to eradicate al-Qaeda and Taliban militants. There are seven tribal areas known as agencies in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas: Bajaur, Mohmand, Khyber, Orakzai, Kurram, North Waziristan and South Waziristan and six smaller zones called Frontier Regions. The region contains rugged mountains, barren hills, and deep valleys with most human habitation in open valleys in extensive floodplains where soil is fertile and tributaries provide irrigation water [8]. There are 3.3 million people in the FATA, most of which are ethnic Pashtuns that live under their own century-old rules and regulations [9]. The domestic affairs of tribes are regulated through “Pakhtunwali” or code of conduct designed on the principles of equity and retaliation [8]. The FATA is one of the poorest, most isolated, and dangerous regions of Pakistan.

2.2. GIS and Remote Sensing Methods

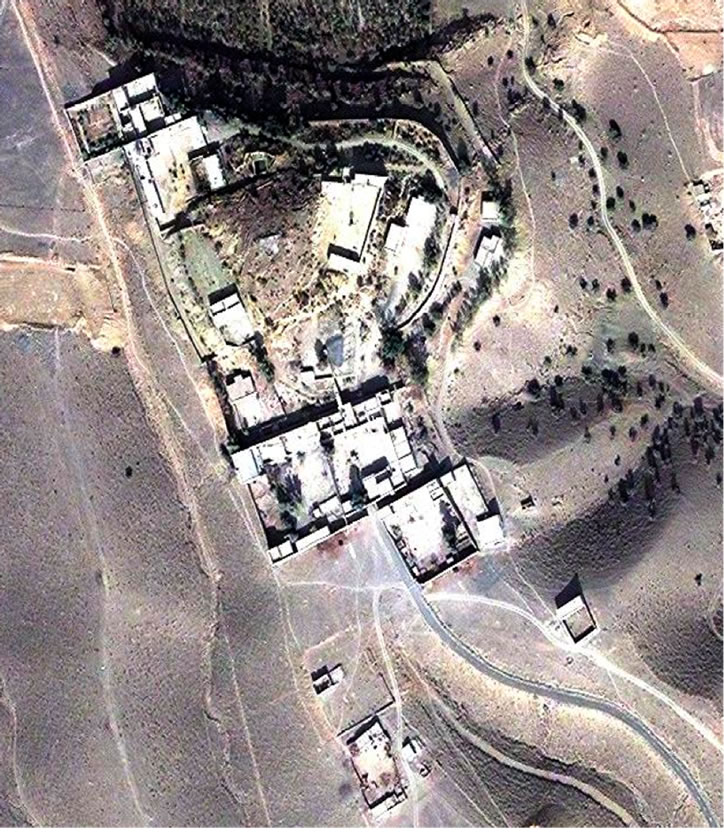

Data on the location of potential drone bombing was collected from the Center for American Progress, which provides estimated location and casualty data for the FATA [3]. The locations of potential drone bombing from 2004 to December 31, 2009 were entered into ArcMap 9.2. The region with the highest number and density of drone bombings was identified, and a QuickBird 2 image was purchased from GeoEye over the region. QuickBird 2 provides 0.41 m resolution data in the panchromatic and 1.65 meter data in the multi-spectral. A clear image was purchased from November 9, 2009 (ID:101001000A95C201). Areas that did not contain structures (i.e. natural areas) were cut to reduce the cost of the imagery and to focus on structures in the region. The image cost was $1200 for a 10.6 km2 area and allowed a sufficient view of individual structures in Figure 1. The image was sent in a GeoTIFF format and was uploaded into ENVI 4.8 software.

A systematic search was undertaken in 1 km2 grids to identify structures that showed potential damage from drone bombings. Searches began in the upper left hand corner of each grid and continued east until reaching the easternmost section of the grid or where the image was subset. A 100 m by 100 m window was used to examine the structures for potential drone damage. Potential sites were marked as regions of interest in vector files, then examined by all authors to assess if there were bombed sites. Once potential bombed sites were identified, we examined publicly available Google Earth imagery to identify if there was high-resolution imagery before and after November 2009.

Figure 1. An example of structures in the FATA region from QuickBird 2 imagery.

3. Results

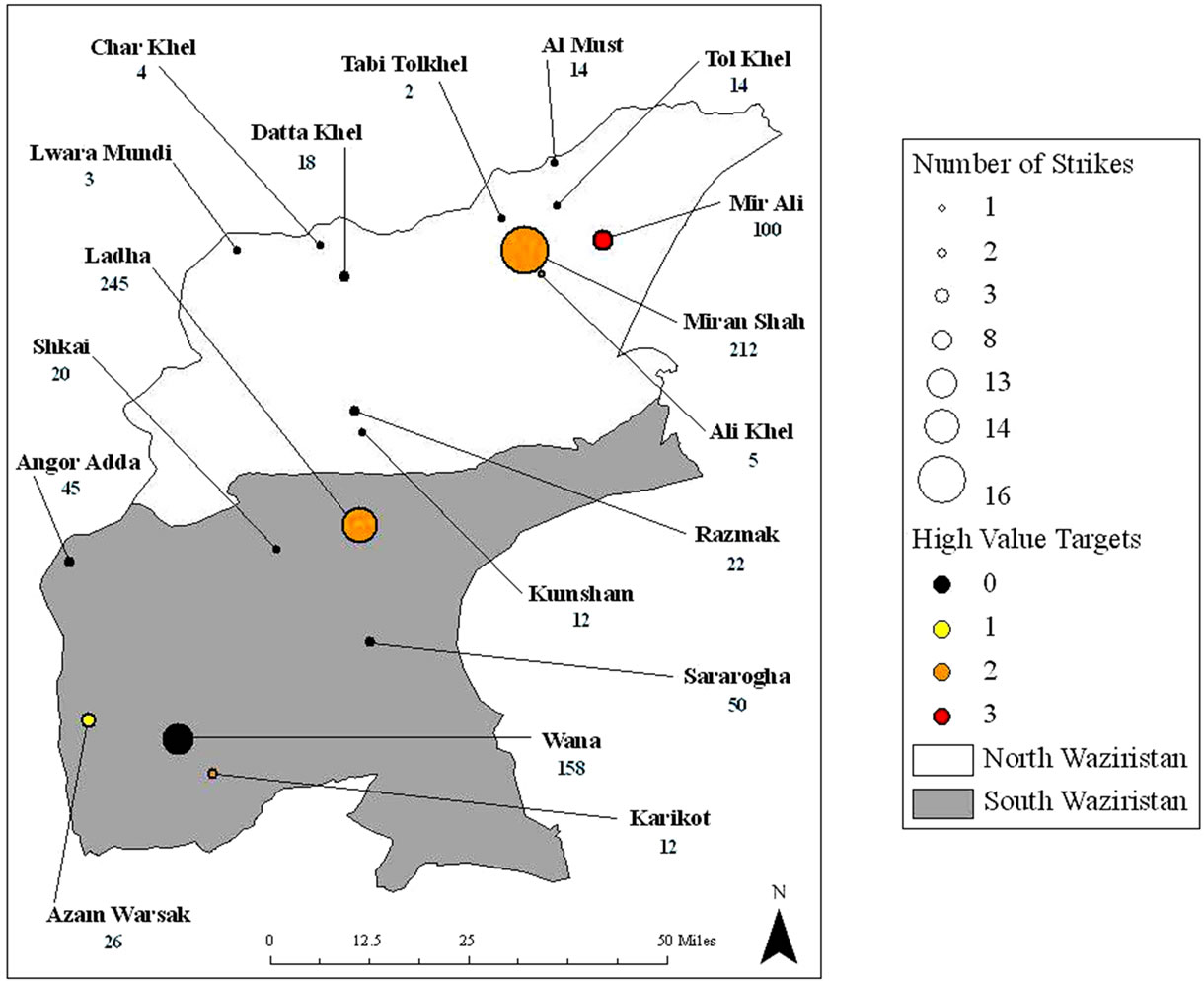

There were 16 drone bombings in Miram Shah in North Waziristan before January 1, 2010, shown in Figure 2. There were an estimated 212 people killed in Miram Shah, which was the highest number in all cities in the FATA. A systematic search was undertaken of the acquired QuickBird 2 image in 1 km2 grids that contained potential drone bombing sites in Figure 3. We identified two structures as potential sites where a drone bombing might have occurred in Figure 4. Figure 4(a) is an irregular structure with wall damage in the center of the structure. However, it is difficult to determine if this is damage from a drone bombing or decay of a structure that has been abandoned. If it is a drone bombing, it could be over 6 months old. Figure 4(b) does appear to be a recently bombed site. There is an unusual plume of sediment away from the structure in the North and burned area damage in black. The blast radius is less than 15 m and the outer walls are still intact. There was no high-resolution image available from Google Earth from before or after November 2009 for the two potential bombed sites.

4. Discussion

The Center for American Progress provides data on the location of drone bombings, target values, and number of casualties. According to the center, information on these strikes was compiled from analysis of “existing open-

Figure 2. Hypothesized location of drone bombings and casualties (blue) before December 31, 2009.

Figure 3. QuickBird 2 imagery with 1 km grid lines of Miram Shah, North Waziristan.

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 4. Potential drone bombing sites from November 2009 QuickBird 2 image.

source reporting”. Sources include the New York Times, Washington Post, BBC, Reuters, Associated Press, Agence France-Press, Dawn, the Daily Times, GEO TV, and secondary source reporting from the Long War Journal and the Jamestown Foundation, among others [3]. Most of the drone bombings were in large cities such as Miram Shah and Ladha that are easy to find on maps and Google Earth. However, we were not able to find the names of smaller towns or rural areas in current GIS databases or Google Earth. Most of these areas were small villages, and news sources were unable to provide an adequate description of the locations. Currently, there are a number of groups besides the Center for American Progress that also provide interactive maps on the locations of drone bombings and militant attacks [10,11]. Standard population centers and village names are still needed for the region in order to adequately assess the accuracy and extent of drone bombings in FATA from all these sources. However, we were able to narrow the location of most of the drone bombings to the capital city of Miram Shah in the FATA.

We feel confident that we were able to identify the location of one drone bombing in Figure 4(b). If the center of the compound is the target, it would appear that the drone bombing is accurate. This also suggests that the blast radius of such attacks is relatively small or less than 20 m. Indeed, the walls still appear to remain intact. This appears similar to blast radii reported for hellfire missiles which are used by both the Predator and Reaper drones [12]. The resolution of QuickBird 2 is currently not high enough to see or quantify casualties.

Our results suggest that drone bombings can be monitored in large towns in the FATA such as Miram Shah. In theory, the high-resolution imagery of Miram Shah is available weekly, especially in the summer when high pressure and low humidity permit the acquisition of high quality imagery. A weekly analysis of a city over one year in FATA would cost approximately $64,000 from GeoEye [13]. This assumes a clear image is available for each week. Although it does appear possible to monitor large towns, it may be prohibitively expensive to monitor the entire FATA region. Indeed, many of the drone bombings have been reported to target vehicles on roads in isolated areas.

We were able to capture an image of a Predator drone flying over the landscape just southwest of Miram Shah in Figure 5. The slight blue discoloration north of the drone is most likely the result of an active lidar (light detection and ranging) sensor that is scanning the landscape and interfering with the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. Although such an image clearly plays into the “spectacle of secret places”, we believe that this is the first satellite image of a drone in the FATA [6]. This suggests that there is a high density of drones in the region because this snapshot was captured during the daytime in a relatively small area.

The public and political science community has access to high-resolution imagery that can be used to assess the impacts or success of a military campaign. However, remote sensing data can be used to monitor important

Figure 5. An MQ-1B Predator drone flying over the landscape on November 9, 2009.

quality of life variables within the FATA and cross border regions in Afghanistan. In theory, US policy in southern Afghanistan and the FATA can be assessed using remote sensing imagery over a number of spatial scales. Ethnic groups in the FATA are extremely independent, operate at a tribal level, and do not always accept government aid or intervention [8]. According to The United States Agency for International Development, there is no US humanitarian aid access to the FATA [14]. Thus, the success of the US controlled areas can be compared to the FATA areas using remote sensing. The development of infrastructure such as roads and buildings is easy to quantify with high-resolution imagery [15]. High-resolution imagery can also be used to compare changes in agricultural areas, crop type, and crop health along with assessing the transportation activity in a region by examining cars and buses [16]. Moderate-resolution imagery such as free Landsat and MODIS imagery can be used to assess large-scale patterns of agricultural productivity, hydrology, and land cover change [16,17]. Finally, nightlight imagery can be used to estimate increases and decreases in energy within the region [5].

5. Conclusion

It is possible for the public to monitor drone bombings in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan. However, monitoring and comparing quality of life indicators in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and southern Afghanistan using a diversity of satellites may have a more profound impact on the general public and policymakers. Results suggest that there should also be some concern with the use of drones in further “technologizing” warfare. The results also shed light on the issue of Pakistan’s territorial sovereignty and US intervention. The continued use and development of drone technology may open the door to counterattacks on the US from whoever acquires access to the technology.

6. Acknowledgements

We thank Dave Northup, Christopher Santiago, Alandre Martin, and Thalia Edelman for help with research. We thank John May, John Agnew, and Stephanie Pincetl for comments and suggestions on this manuscript. The California Center for Population Research, UCLA provided funding through the Spatial Demography Program.

REFERENCES

- M. E. O’Connell, “Unlawful Killing with Combat Drones: A Case Study of Pakistan,” Notre Dame Legal Studies Research Paper, Vol. 43, No. 9, 2009, pp. 2-26.

- B. R. Posen, “The Struggle against Terrorism: Grand Strategy, Strategy, and Tactics,” International Security, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2001, pp. 39-55. doi:10.1162/016228801753399709

- The Center for American Progress, “US Airstrikes in Pakistan on the Rise,” 2009. http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2009/03/pakistan_map.html

- R. A. Beck, “Remote Sensing and GIS as Counterterrorism Tools in the Afghanistan War: A Case Study of the Zhawar Kili Region,” The Professional Geographer, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2002, pp. 188-190. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.5502005

- J. Agnew, T. W. Gillespie, J. Gonzalez and B. Min, “Baghdad Nights: Evaluating the US Military “Surge” Using Nighttime Light Signatures,” Environment and Planning, Vol. 40, No. 10, 2008, pp. 2285-2295.

- C. Perkins and M. Dodge, “Satellite Imagery and the Spectacle of Secret Spaces,” Geoforum, Vol. 40, No. 4, 2009, pp. 546-560. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.04.01

- L. Parks, “Digging into Google Earth: An Analysis of ‘Crisis in Darfur’,” Geoforum, Vol. 40, No. 4, 2009, pp. 535-545. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.04.004

- A. H. Siddiqi, “Society and Economy of the Tribal Belt in Pakistan,” Geoforum, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1987, pp. 65-79. doi:10.1016/0016-7185(87)90021-2

- Government of Pakistan, “Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Federally Administered Tribal Areas,” Planning and Development Department, FATA Secretariat, Peshawar, 2009.

- British Broadcasting Corporation, “Mapping US Drone and Islamic Militant Attacks in Pakistan,” 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-10648909

- New America Foundation, “The Year of the Drone: An Analysis of US Drone Strikes in Pakistan, 2004-2011,” 2011. http://counterterrorism.newamerica.net/drones

- R. A. Efroymsona, W. Hargrovea, D. S. Jones, L. L. Pater, and G. W. Suter, “The Apache Longbow-Hellfire Missile test at Yuma Proving Ground: Ecological Risk Aassessment for Missile Firing,” Human and Ecological Risk Assessment, Vol. 14, No. 5, 2008, pp. 898-918. doi:10.1080/1080703080238750

- GeoEye, Accessed 10 January 2010. http://www.geoeye.com

- USAID, “USG Humanitarian Assistance to Conflict-Affected Populations in Pakistan in FY 2008 and to date in FY 2009,” 2009, Accessed 2 January 2010. http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900sid/HHOO-7VGTM6?OpenDocument

- J. Park, R. Tateishi, K.Wikantika and J. Park, “The Potential of High Resolution Remotely Sensed Data for Urban Infrastructure Monitoring,” Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Vol. 2, 1999, pp. 1137-1139. doi:10.1109/IGARSS.1999.774557

- J. R. Jensen, “Remote Sensing of the Environment: A Earth Resource Perspective,” Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2007, 592 p.

- K. M. de Beurs and G. M. Henebry, “Land Surface Phenology, Climatic Variation, and Institutional Change: Analyzing Agricultural Land Cover Change in Kazakhstan,” Remote Sensing of Environment, Vol. 89, No. 4, 2004, pp. 497-509. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2003.11.006