Health

Vol. 4 No. 10 (2012) , Article ID: 24073 , 4 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2012.410127

Medical students’ willingness to work in post-conflict areas: A qualitative study in Sri Lanka

![]()

1Department of Public Health and Health Systems, Nagoya University School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan; *Corresponding Author: azeem-gadi@med.nagoya-u.ac.jp

2Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Nugegoda, Sri Lanka

Received 16 August 2012; revised 16 September 2012; accepted 1 October 2012

Keywords: Willingness; Human Resources for Health; Medical Students; Qualitative Study; Post-Conflict; Sri Lanka

ABSTRACT

Background: The north-east (NE) region of Sri Lanka observed a critical health workers’ shortage after the long-lasting armed conflict. This study aimed to explore medical students’ attitudes towards working in the NE and to identify factors determining such attitudes. Methods: A semi-structured, self-administered questionnaire survey was conducted in two medical schools, one in the NE and the other near the capital, in October 2004. Data were qualitatively analysed using the framework approach. Results: Three main themes were identified: 1) Professional motives and career plans; 2) Students’ perceptions of the healthcare situation in the NE; and 3) Students’ choice of the NE as a future practice location. It was found that familiarity with the difficulties faced by the NE people was a major motivation for medical students to work in the NE in the future. For NE students, familiarity was linked to their sense of belonging. For non-NE students, their personal experience of the NE familiarized them with the difficult situation there, which positively influenced their willingness to work there. Demotivations to work in the NE were poor working and living conditions, fewer opportunities for postgraduate education, language differences, insecurity, and fear of an unpleasant social response from the NE communities. Conclusions: NE local medical students had a sense of belonging to the NE and compassion for the Tamil people as members of the ethnic group. They were willing to work in the NE if their concerns about difficult working and living conditions and postgraduate education could be solved. Non-NE students who were familiar with the NE situation through their personal experience also showed a willingness to work there; thus, early exposure programmes in medical education might help to increase the health workforce in the NE. It is also expected that non-NE physicians working for the NE people would facilitate reconciliation and the rebuilding of trust between two ethnic groups.

1. INTRODUCTION

A shortage of physicians has often been observed as one of the deleterious consequences of the armed conflict. [1] Medical personnel flee from the affected area, and those from outside do not want to work there. Insecurity, damaged health infrastructure, work overload, and disrupted livelihood are the most common factors associated with an abrupt shortage of human resources for health (HRH) in war-torn areas [2-5] . Loss of healthcare workers, particularly physicians, leads to ineffective healthcare delivery [2,6,7] . The adverse consequences of a shortage of HRH are, for example, increased maternal and infant mortality in post-conflict countries [1,8]. Restoring health workers’ availability in post-conflict settings becomes far more challenging compared to other types of underprivileged settings, such as rural or remote areas and the areas of minority ethnic communities.

Programmes targeted at attracting health professionals to severely under-resourced settings have achieved varying degree of success [9-11] . Particularly in the post-conflict reconstruction, heavy spending without proper needs assessment leads to less effective outcomes [12].

Motivating health professionals for placement in underserved settings is broadly determined by the level of understanding of the community concerned [10,13,14] , the cultural norms, and organizational determinants such as good human resources management [15]. In post-conflict situations, deterioration of the health system as a whole, social tensions between the confronting groups and the destroyed economy are additional challenges [1,9,16] .

Sri Lanka has been known to have satisfactory health and other social indicators compared to similar middleincome countries, as the government has invested in social development programmes such as free education and health services [17-20] . For example, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) was 24 per 100,000 live births in 1996. [4] However, a longstanding war has affected the north-east (NE) region of the country, which had been the battlefield between a pro-independent Tamil militant organization called Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) and the Sinhalese-dominant Sri Lankan government armed forces since 1983 [20].

A shortage of physicians was one of the most important and urgent healthcare problems in the NE [4]. Before the conflict, the average number of physicians per population in the NE was above the national average. However, it rapidly declined to half by 1996, while the national average continued in consistent progress [4]. Even after the peace agreement in February 2002, the number of physicians per 100,000 residents decreased from 22 in 2001 to 15 in 2003, which was one-fourth of the national average. [4] Health indicators also deteriorated significantly: MMR was as high as 153 per 100,000, and infant mortality was five times higher than that of the national average in some of the NE districts in 2003. Lack of specific medical instruments and treatment at referral hospital were among many other critical issues [4,20].

Sri Lankan medical students have the potential to fill such a shortage of physicians in the future; thus, it is important to know whether or not they are willing to work in the NE in their future and what factors contribute to that willingness. This study aimed to explore attitudes of Sri Lankan medical students towards practicing in the NE and to identify factors determining such attitudes.

2. METHODS

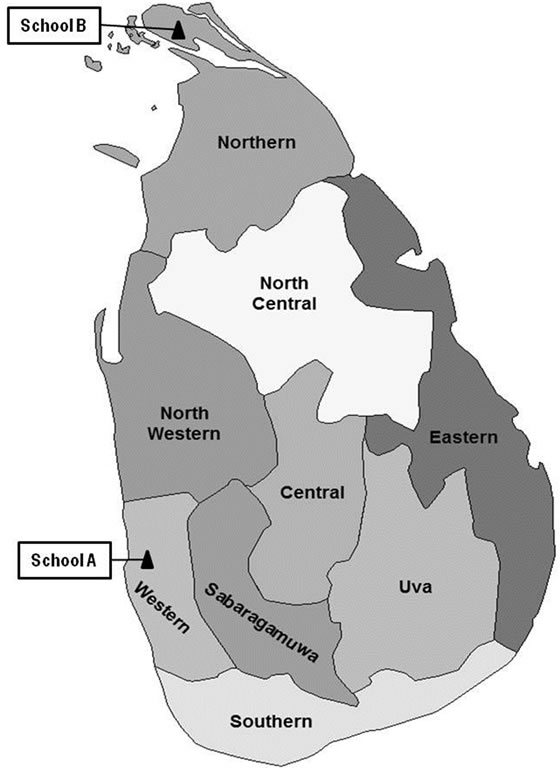

A self-administered, semi-structured questionnaire survey was conducted with undergraduate students of two Sri Lankan medical schools in October 2004. School A, located near the capital, was purposively selected. It had students of all ethnicities from the whole country, but the Sinhalese were in majority. School B was the only medical school in the NE region at the time of study. It had almost all students who were of NE origin. Figure 1 shows the approximate location of the schools on the map.

The questionnaire was written in English and consisted of 14 components: reasons or circumstances making students join the medical profession and their career plans (2 questions), knowledge of the healthcare system situation in the NE and in Sri Lanka as a whole (8 questions), and agreement or disagreement with working anywhere in the NE after completing their ongoing study (4 questions). The questionnaires were distributed among the students and collected over a period of two weeks.

The questionnaires and the written information were distributed to all undergraduate students of the certain grades in the both schools. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. They were assured of the confidentiality of their personal information as well as of the opinions they would give. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka.

The respondents answered the questions in English and they were literally transcribed without any translation and summarization. The transcribed text data were then analysed using the framework approach, which consists of familiarization with the data, identifying a thematic framework, indexing the data and charting them according to the thematic framework identified, and their final mapping and interpretation [21].

3. RESULTS

In total, 192 responses out of 199 were selected for the analysis after excluding those with insufficient and irrelevant information. Of the sixty-two respondents from

Figure 1. Location of school A and school B on the Sri Lankan map. (The author modified the map after downloading from the Wikipedia web source: http://upload.wikimedia.org./wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Sri_Lanka_Provinces) accessed on 2012-08-24.

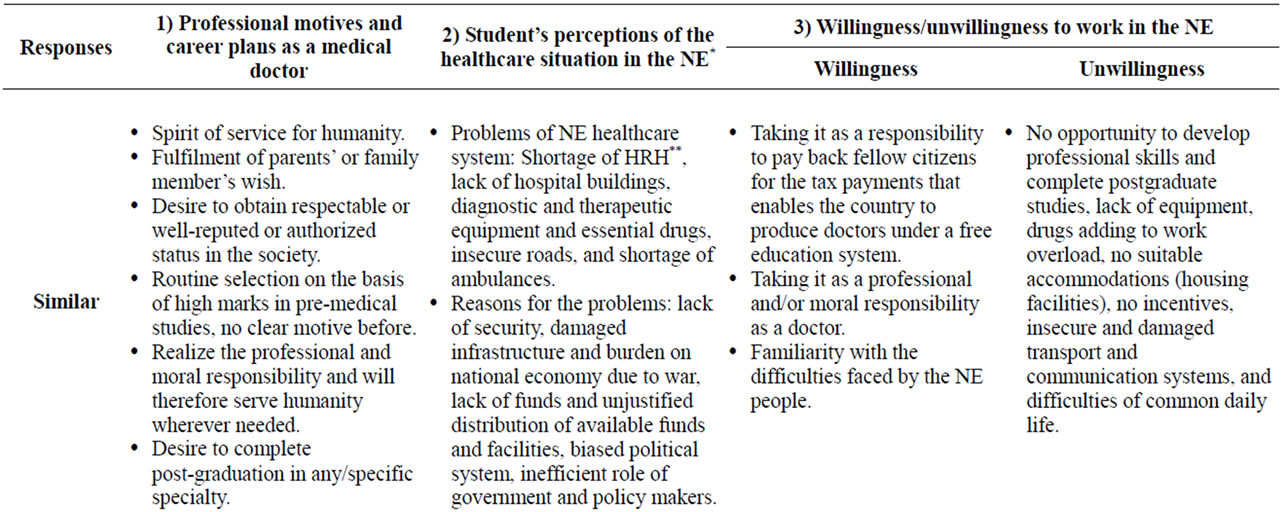

Table 1. Similar and different responses by NE residents and non-residents, as categorized under three research themes.

school A, all were Sinhala except one with neither Sinhala nor Tamil ethnicity, and all were living outside the NE. The male-to-female ratio was 28 to 34. All 130 respondents from school B were Tamil people from the NE, and the male-to-female ratio was 54 to 76.

Three main themes were identified in the textual data. Theme 1, “professional motives and career plans”, covered general views as a medical doctor. Theme 2, “students” perceptions of the healthcare situation in the NE’, gathered descriptions of strengths and weaknesses of the NE healthcare situation compared with that of Sri Lanka as a whole. Theme 3, “students” choice of the NE as a future practice location, took account of future availability for working in the NE. Similarities and differences between respondents of the two schools are shown in Table 1. Both schools’ students responded similarly under theme 1, while differences between the two schools were observed under themes 2 and 3.

3.1. Professional Motives and Career Plans

The majority of the respondents, regardless of the university, grade, ethnicity, or gender, suggested that they joined the medical field because they hoped to serve or dedicate themselves to humanity. Some respondents hoped to serve people affected by the war. This was stated as:

“From a younger age, I wanted to be a person who can help other people. So being a doctor, I can help people when they are ill and helpless in war situation. So I decided to study medicine.” (A)

“I like to do good service for my motherland and for suffering people who live in war affected areas like Anuradhapura.” (A)

Many students intended to satisfy their parents’ wishes, and others stated automatic selection on the basis of high marks in pre-medical studies as motives for becoming a doctor. The desire for social and economical prestige also appeared as another possible reason:

“I don’t know why and when this idea of becoming a doctor occurred in my mind. I think it was internalized by my parents and society from my childhood. In our society, doctors are looked up to and respected. Actually, I didn’t decide anything. Everything occurred itself.” (B)

“To serve the people, to earn the money, and to be accepted as a highly educated person in the community.” (B)

“To be a respectable person in the society, by doing a greater social service, and to obtain knowledge to uplift the health of people in rural areas.” (A)

Many students in both groups wanted to achieve postgraduate qualifications and maximize their professional skills:

“In Sri Lanka, there are only a few specialists in government hospitals. So I want to pursue my higher studies in another country and come back to Sri Lanka and work as a specialist in some field in a government hospital.” (A)

3.2. Students’ Perceptions of Healthcare Situation in the NE

Most students in both schools were aware of the deteriorated situation in the NE including shortage of HRH, especially physicians; shortage of health facilities, medical equipment, ambulances and essential drugs; and damaged roads and communication facilities. Most of them thought that diversion of the budget to the war left nothing to spend on healthcare and other social services.

Some of the students of school B had different opinions from those of school A regarding “who was responsible for the overall deprived condition of the NE” the Sinhala-dominant Sri Lankan government or the LTTE. They thought that underlying causes of such deprivation included ethnic discrimination, lack of planning, and unequal or unjustified allocation of available resources:

“LTTE, politicians of all parties are responsible for not having a permanent solution for this.” (A)

“The government’s part (in development) is very poor. But LTTE has done the most important part in northeastern provinces. They do very hard work to prevent our community against health problems.” (B)

3.3. Students’ Choice of the NE as Future Practice Location

Some students were willing to work in the NE because they regarded it as their responsibility to work anywhere for the Sri Lankan people. This sense of responsibility was a way to pay back because their education was free of charge and supported by the national budget. Taking it as their professional and ethical duty, some students expressed a commitment to serve wherever required beyond any social or geographical specifications within Sri Lanka.

“The government tax fees collected from Sri Lankans have enabled my education. So I like to work for them anywhere in Sri Lanka.” (A)

“As a doctor, my duty is to help needy sick people, it doesn’t matter where they are from or who they are, e.g., Colombo or from Trincomalee, or Jaffna, Sinhala, Tamil Muslim or Japanese. So I spend the rest of my life for their happiness.” (A)

For Tamil students, prominent reasons for desiring to work in the NE included having a hometown located in the NE, speaking the same language and having the same ethnicity and sympathy for the war-affected NE people.

“Yes, Jaffna, as it is easier to work there than in other areas as it is my home place, and it is easier to contact others than in other provinces because most of them speak the Tamil language.” (B)

“I will work where the Tamil people suffer from war in north-eastern provinces. I suffered a lot, I know what happens if a person has illness during a war situation.” (B)

Only a few Tamil students ruled out any possibility of working in the NE, fearing that it might compromise their expected socioeconomic status in the future.

“I am from north-eastern provinces and I studied and spent about 1/4 of my life in the poor situation. So I would like to go outside from this area.” (B)

A few Sinhala students answered that they were willing to work in the NE. Such motivation was caused by their personal experiences of the situation, as they had visited the NE.

“I want to work in Trincomalee. I was there for 5 days during my 2nd year of medical school. The people with whom I stayed were in a refugee camp, but the way they cared for me and accepted me was very warm, despite the fact that I am a Sinhalese. I came away knowing all sorts of difficulties they are having during those few 5 days. So I felt like doing something for them whenever possible.” (A)

“I am willing to work in Vavuniya. I have visited these areas, and have seen how these people are suffering.” (A)

Reasons for reluctance to work in the NE that were commonly observed in both groups included lack of postgraduate learning opportunities, overload of work, poor living conditions such as lack of government quarters for doctors, and absence of any special incentives. Many students were also uncertain about the reliability of the peace agreement and feared that the war might start again.

“We have to work without proper facilities and sources. We can’t improve us or study for our further development. A postgraduate institute and classes should be in the north-eastern province. All the sources should be given as in Colombo. Medical sessions, seminars, discussion should be done.” (B)

“Possible obstacles to work in NE are 1) Facility problems, inadequacy of safety, proper accommodations, with minimum facilities; 2) Financial problems; they don’t get satisfactorily paid for their risk of working in such an area.” (A)

Major factors causing unwillingness among the Sinhalese students were security concerns and a communication gap due to language differences. They also pointed out a few other obstacles, such as lack of knowledge of the NE situation and fear of offensive social responses from the NE Tamil people.

“Personally, I would like to mention that with the ongoing conflict my parents would be in a very insecure position because I’m the only child, if I choose to serve there. Therefore, relatives in the south should be given proper assurance.” (A)

“No, I can’t work in the NE, mainly because of the language problem. I can’t understand a single Tamil word. So how can I diagnose a disease without knowing a history? All Sri Lankans should study Sinhala as well as Tamil or make a common language to all, English the better.” (A)

“Since I haven’t actually been there and I don’t know anyone there, I don’t know the real situation. It is not easy to get correct information from the media alone.” (A)

Some of the Sinhalese also had negative attitudes towards Tamils.

“According to my knowledge, there are enough doctors who are Tamil practicing in Colombo merely for money, and they should be encouraged to work at their own towns. Tamil don’t like to serve their own people. Avoid Tamil doctors from Jaffna, doing their internship in Colombo.” (A)

4. DISCUSSION

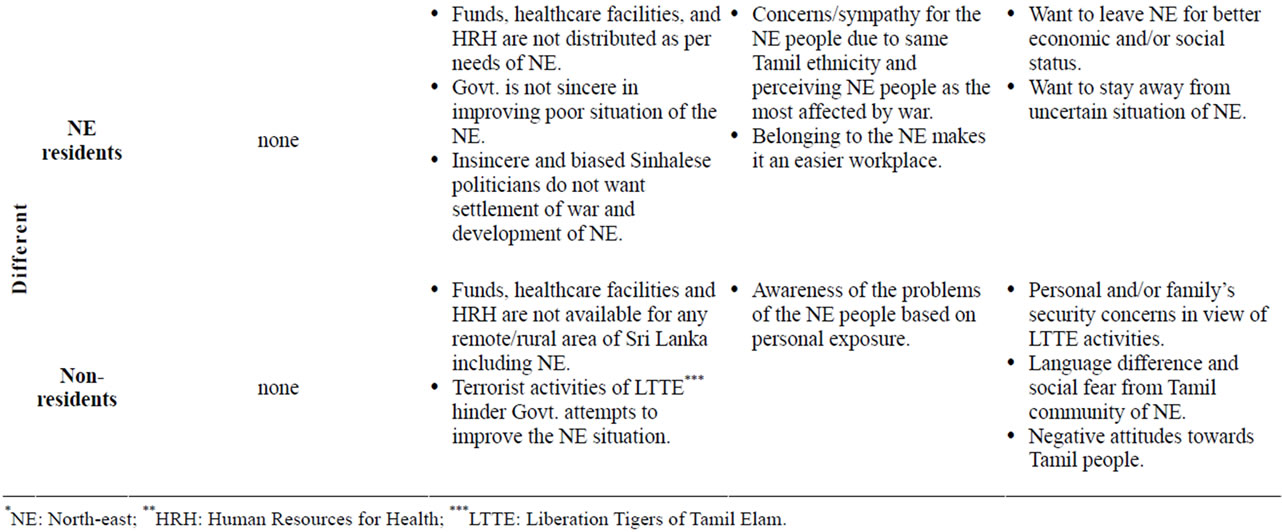

The findings of the study suggested that the students who were familiar with difficulties faced by the NE people were willing to work in the NE. Figure 2 illustrates three main themes identified (“willingness to work in the NE”, “perceptions of the NE situation”, and “professional motives and career plans”) and factors that influenced students positively (motivations) and negatively (demotivations).

NE students explained their familiarity with the NE as mainly based on their sense of belonging. Using the same language seemed to be an advantage compared to nonTamil speakers who expressed possible communication difficulties in the NE. Previous studies indicated the preference of hometown-based practice among healthcare professionals [22-25] . In addition, as members of the same ethnic group, students with NE origins expressed their

Figure 2. Factors influencing the willingness to work in the NE.

commitment and compassion for the Tamil people in the NE. They described Tamil people as politically underrepresented, neglected by the Sinhala majority, and the most affected by the conflict. Other studies have suggested that the wish to serve the underserved and underrepresented minority of one’s own kind, such as black medical students in the United States, would contribute to keeping health professionals working for them [26,27] . Thus, students with NE origins are the most likely to comprise the workforce in the NE.

A couple of non-NE students expressed their familiarity with the NE due to their personal observations of difficulties faced by the NE people during private visits to the region. Their concern for the NE situation positively influenced their willingness to work there. On the contrary, non-NE students who lacked such experience simply feared unpleasant social responses from the Tamil community and were reluctant to work in the NE. The United States faced disparity of healthcare services delivery among the poor and non-poor specially the white and non-white ethnic populations between 1960 and 1986. [28] To eliminate the disparities one of the targets was producing physicians who would be willing to work in medically underserved areas. Commitment to Underserved People (CUP) programme included one of them. It was a pre-service exposure programme for medical students and junior doctors aimed at raising their willingness to work in the underserved populations. The CUP curriculum was designed to maintain students’ involvement throughout all 4 years of their training. The CUP programme was found sustainable and cost-effective with average budget of $3000 per year. [13] There might not be enough NE students to fill the shortage of physicians in the NE, but provided with a proper exposure program, non-NE students would be willing to work in the NE.

It should be noted that non-NE physicians working in the NE might play a role in facilitating the process of reconciliation and rebuilding trust between the two confronting groups. Non-NE physicians and NE people would share the same concern regarding health issues; thus, mutual understanding between the two groups might be facilitated. Rebuilding social trust and developing a mutual understanding among different stakeholders is one of important challenges of post-conflict reconstruction [5,29]. Our previous study in post-conflict Cambodia found that participatory training of health workers, including former militants, facilitated reconciliation using health as a common interest [30]. The World Health Organization (WHO) set up the “Health as a Bridge for Peace” concept and has been promoting the integration of peace-building strategies into health activeties and health-sector development [31]. Encouraging the non-NE students to work together with the NE communities would contribute to development of a healthy social relationship between the two groups of people.

Other obstacles identified by students of both schools were difficult working conditions due to a shortage of equipment and medical supplies, fewer opportunities for learning and career development, lack of financial incentives, and poor living conditions. These are common problems observed in post-conflict settings especially rural remote areas, [5] and they need to be addressed in the context of overall economic and social development of underprivileged areas. Security issues need to be addressed urgently, as insecurity owing to the war made students avoid working in the NE.

Our study contributed to the understanding of underlying causes for the shortage of physicians in post-conflict areas, a problem that policy makers need to address in order to rebuild healthcare services. Limitations of the study are as follows: responses might not be rich enough because of the self-administered questionnaire survey in English, which was not the respondents’ mother tongue. In addition, there might be selection biases because, with one exception, only Sinhalese students responded to the questionnaire in school A that was composed of students from various ethnic groups.

5. CONCLUSIONS

NE local medical students had a sense of belonging and compassion for the Tamil people as members of this ethnic group, and they were willing to work in the NE if their concerns about difficult working and living conditions could be resolved. Non-NE students who were familiar with the NE situation through their personal experience also showed a willingness to work there; thus, early exposure programmes in medical education might help to increase the health workforce in the NE. It is also expected that non-NE physicians working for the NE people would facilitate reconciliation and rebuild trust, which is presently lacking between the two ethnic groups.

After the data of this study collected, Sri Lankan armed conflict was over in 2009. Despite major sociopolitical and economic changes in recent years, however, disparity between NE and non-NE still exists [32,33]. The results of this study provide practical implications in the study areas, and more importantly, which will inform to other areas in similar situations. This study highlights lessons learned to post-conflict NE region in Sri Lanka as well as to other areas.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was financially supported in part by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B, 14390025) to AA sponsored by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. We would like to thank Dr. Etsuko Kita for providing valuable advice on post-conflict public health issues. We also would like to thank the following organizations and people for cooperating the data collection: Ministry of Health, Government of Sri Lanka; dean, faculties and students of Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna; faculties and students of Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura; Dr. Mari Nagai; Dr. Soichiro Imaeda; Association of Medical Doctors of Asia; and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Sri Lanka Office.

REFERENCES

- Waters, H., Garrett, B. and Burnham, G. (2007) Rehabilitating health systems in post-conflict situations. World Institute for Development Economic Research (UNUWIDER).

- Betsi, N.A., Koudou, B.G., Cisse, G., Tschannen, A.B., Pignol, A.M., Ouattara, Y., Madougou, Z., Tanner, M. and Utzinger, J. (2006) Effect of an armed conflict on human resources and health systems in Côte d’Ivoire: Prevention of and care for people with HIV/AIDS. Aids Care: Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 18, 356-365. doi:10.1080/09540120500200856

- Keane, V. (1996) Health impact of large post-conflict migratory movements: The experience of Mozambique: Maputo, 20-22 March 1996, international workshop organized by International Organization for Migration in collaboration with Ministry of Health, Mozambique. International Organization for Migration, Geneva.

- Nagai, M., Abraham, S., Okamoto, M., Kita, E. and Aoyama, A. (2007) Reconstruction of health service systems in the post-conflict Northern Province in Sri Lanka. Health Policy, 83, 84-93. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.12.001

- Devkota, B. and van Teijlingen, E.R. (2009) Politicians in Apron: Case study of rebel health services in Nepal. AsiaPacific Journal of Public Health, 21, 377-384. doi:10.1177/1010539509342434

- Chen, L., Evans, T., Anand, S., Boufford, J.I., Brown, H., Chowdhury, M., Cueto, M., Dare, L., Dussault, G., Elzinga, G., Fee, E., Habte, D., Hanvoravongchai, P., Jacobs, M., Kurowski, C., Michael, S., Pablos-Mendez, A., Sewankambo, N., Solimano, G., Stilwell, B., de Waal, A. and Wibulpolprasert, S. (2004) Human resources for health: Overcoming the crisis. The Lancet, 364, 1984-1990. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17482-5

- WHO (2006) The world health report 2006: Working together for health. World Health Organization.

- WHO (2005) World health statistics 2005. World Health Organization.

- Ohiorhenuan, J.F.E. and Stewart, F. (2009) Crisis prevention and recovery report 2008: Post-conflict economic recovery, enabling local ingenuity. United Nations Development Library.

- George, A., Menotti, E. P., Rivera, D., Montes, I., Reyes, C.M. and Marsh, D.R. (2009) Community case management of childhood illness in Nicaragua: Transforming health systems in underserved rural areas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 20, 99-115. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0205

- Reid, S. (2004) Monitoring the effect of the new rural allowance for health professionals. Health Systems Trust. Durban.

- Kruk, M.E., Freedman, L.P., Anglin, G.A. and Waldman, R.J. (2010) Rebuilding health systems to improve health and promote statebuilding in post-conflict countries: A theoretical framework and research agenda. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 89-97. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.042

- Campos-Outcalt, D., Chang, S., Pust, R. and Johnson, L. (1997) Commitment to the underserved: Evaluating the effect of an extracurricular medical student program on career choice. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 9, 276-281. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm0904_6

- Fyffe, H.E. and Pitts, N.B. (1989) Origin, training, and subsequent practice location of Scotland general and community dentists. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 17, 325-329. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00648.x

- Mathauer, I. and Imhoff, I. (2006) Health worker motivetion in Africa: The role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools. Human Resources for Health, 4, 24. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-4-24

- Ranasinghe, A. and Hartog, J. (2002) Free-education in Sri Lanka. Does it eliminate the family effect? Economics of Education Review, 21, 623-633. doi:10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00038-3

- Jayasinghe, K.S.A., De Silva, D., Mendis, N. and Lie, R.K. (1998) Ethics of resource allocation in developing countries: The case of Sri Lanka. Social Science & Medicine, 47, 1619-1625. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00110-5

- Jayasekara, R.S. and Schultz, T. (2007) Health status, trends, and issues in Sri Lanka. Nursing & Health Sciences, 9, 228-233. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00328.x

- Paskins, Z. (2001) Sri Lankan health care provision and medical education: A discussion. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 77, 139-143. doi:10.1136/pmj.77.904.139

- National Council for Economic Development (NECD) of Sri Lanka (2005) Millennium development goals country report 2005. National Council for Economic Development (NECD) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

- Ritchie, J. and Lewis, J. (2003) Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage Publications Ltd.,

- Rabinowitz, H.K., Diamond, J.J., Markham, F.W. and Paynter, N.P. (2001) Critical factors for designing programs to increase the supply and retention of rural primary care physicians. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 1041-1048. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1041

- Mullan, F. and Frehywot, S. (2007) Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. The Lancet, 370, 2158-2163. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60785-5

- de Vries, E. and Reid, S. (2003) Do South African medical students of rural origin return to rural practice? South African Medical Journal, 93, 789-793.

- Barrett, F.A., Lipsky, M.S. and Lutfiyya, M.N. (2011) The impact of rural training experiences on medical students: A critical review. Academic Medicine, 86, 259-263. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182046387

- Gray, L.C. (1977) The geographic and functional distribution of black physicians: Some research and policy considerations. American Journal of Public Health, 67, 519-526. doi:10.2105/AJPH.67.6.519

- Tekian, A. (1997) A thematic review of the literature on underrepresented minorities and medical training, 1981- 1995: Securing the foundations of the bridge to diversity. Academic Medicine, 72, S140-S146. doi:10.1097/00001888-199710001-00047

- Pappas, G., Queen, S., Hadden, W. and Fisher, G. (1993) The increasing disparity in mortality between scioeconomic groups in the United-States, 1960 AND 1986. The New England Journal of Medicine, 329, 103-109. doi:10.1056/NEJM199307083290207

- Marlowe, P. and Mahmood, M.A. (2009) Public health and health services development in postconflict communities: A Case study of a safe motherhood project in east Timor. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 21, 469- 476. doi:10.1177/1010539509345520

- Ui, S., Leng, K. and Aoyama, A. (2007) Building peace through participatory health training: A case from Cambodia. Global Public Health, 2, 281-293. doi:10.1080/17441690601084691

- Emergency and Humanitarian Action (EHA) (2003) Health as a potential contribution to peace realities from the field: What has WHO learned in the 1990s? Emergency and Humanitarian Action (EHA)/World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva.

- Uyangoda, J. (2010) Sri Lanka in 2009: From civil war to political uncertainties. Asian Survey, 50, 104-111. doi:10.1525/as.2010.50.1.104

- Goodhand, J. (2012) Sri Lanka in 2011 consolidation and militarization of the post-war regime. Asian Survey, 52, 130-137. doi:10.1525/as.2012.52.1.130