Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.08 No.03(2017), Article ID:74480,43 pages

10.4236/jmp.2017.83026

Guidelines to Quantum Field Interactions in Vacuum

Frédéric Schuller1, Michael Neumann-Spallart2, Renaud Savalle3

1Laboratoire de Physique des Lasers, Villetaneuse, France

2Groupe d’Etude de la Matière Condensée, CNRS/Université de Versailles/Université de Paris-Saclay, Paris, France

3CNRS/Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, Paris, France

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: January 17, 2017; Accepted: February 25, 2017; Published: February 28, 2017

ABSTRACT

In this treatise we stress the analogy between strongly interacting many-body systems and elementary particle physics in the context of Quantum Field Theory (QFT). The common denominator between these two branches of theoretical physics is the Green’s function or propagator, which is the key for solving specific problems. Here we are concentrating on the vacuum, its excitations and its interaction with electron and photon fields.

Keywords:

Quantum Vacuum, Quantum Electrodynamics, Quantum Field Theory, Relativistic Quantum Mechanics, Feynman Diagrams

1. Introduction

It is the aim of this treatise to pay tribute to Feynman’s propagator method and its visualization in Feynman diagrams. This method has applications as wide as e.g. many electron theories, condensed matter physics and quantum field theory.

It consists on one hand of showing for intricate mathematical expressions of the underlying physics, and on the other hand, of applying pre-established rules to these graphs, to set up these expressions.

Here we are not giving a lecture on these procedures; we are merely applying them to vacuum excitations interacting with electron and photon fields.

Starting from routinely used techniques as e.g. developed in the book by M. E. Peskin and D. V. Schroeder [1] , we introduce some novelties in the derivation of final results. In particular, a discussion of the electron self-energy result in terms of a Zitterbewegung is presented.

In a first introductory part, we recall the basic facts of the second quantization of the Klein-Gordon and the Dirac field and discuss the resulting consequences.

Then we define propagators for the Dirac and photon fields and use them to treat interactions of these fields with the vacuum. More specifically we study the electron and photon self-energies.

We do not concern ourselves in general with collisions between elementary particles, although this is one of the main subjects met in Quantum Field Theory. As an exception we consider however electron-electron scattering because of its connection with vacuum polarization. The resulting physical facts are discussed extensively.

2. Particles and Fields

It is the aim of this section to recall how, in relativistic quantum physics, negative energy states are avoided by adopting the field viewpoint. For this purpose we chose as the simplest possible case that of an uncharged particle obeying the Klein-Gordon equation. The essential arguments developed here then apply equally to the case of more general systems.

Negative energy states, causality.

In quantum mechanics we associate a particle with a wave function  depending on time and space coordinates

depending on time and space coordinates  and

and  respectively. The wave functions are solutions of a differential equation known as the Schrödinger equation. In a heuristic way this equation can be derived by replacing the energy and momentum of the particle by operators, according to the relations

respectively. The wave functions are solutions of a differential equation known as the Schrödinger equation. In a heuristic way this equation can be derived by replacing the energy and momentum of the particle by operators, according to the relations

and

and

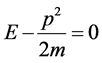

For a particle we then have in the non relativistic case  yielding

yielding

(2.1)

(2.1)

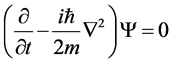

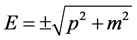

In the relativistic case we start from the relation  and obtain, after inserting the relevant differential operators

and obtain, after inserting the relevant differential operators

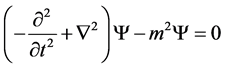

(2.2)

(2.2)

This relativistic version of the Schrödinger equation is called the Klein-Gordon equation. It is important to note that in contrast to the non relativistic Equation (2.1) the Klein-Gordon equation contains the second time derivative meaning that it allows for negative energy solutions. Using from now on natural units ,

,  , we write explicitly

, we write explicitly

(2.3)

(2.3)

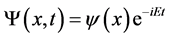

Setting

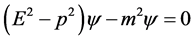

Equation (2.3) reduces to

(2.4)

(2.4)

where we have used .

.

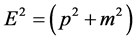

For plane wave solutions with , we then have the energy relations

, we then have the energy relations

(2.5a)

(2.5a)

(2.5b)

(2.5b)

Hence there are negative energy solutions. The question arises whether these solutions cannot be discarded as non physical. But in that case we would not have a complete set of basic functions since these solutions are part of it. In actual calculations this could yield erroneous results. Furthermore, in a less obvious way, omitting these solutions leads to a violation of the principle of causality as we shall demonstrate now.

Consider the amplitude

Inserting the wave functions

we have

Using polar coordinates as follows:

we arrive after integration over

For simplicity we set

up to a rational function of

Bessel function reduces essentially to the exponential

for

Given this factor in the expression of

There are however other shortcomings contained in the relativistic particle theory. One could argue that any positive energy state must be unstable since after some time the particle would fall into a lower energy state, in the same way as an atomic electron in an excited state falls into the ground state after some short lifetime. In the case of fermions this can be prevented by assuming, following Dirac, that all negative energy states are occupied already. This situation is due to the fact that, according to the Pauli principle, each state can only receive one electron. The completely filled negative states constitute the Dirac sea. Moreover, this picture has led Dirac to the prediction of the positron, i.e. a positively charged electron, appearing as a hole in the Dirac sea when by some process an electron is removed from it.

It is however possible to give a less artificial description of relativistic quantum particles by adopting the field viewpoint which will be presented now.

Lagrangian field method

We consider a field function

relation with

indices belong to the Minkowski four-space, Latin ones to ordinary space, with

In analogy with classical mechanics, we introduce a Lagrange function, having here the character of a density, given by the expression

Note also the complementary relation

action integral

Varying this integral in the usual way according to the relation

and using the identities

we arrive at

The last term in the parenthesis can be seen as the four-divergence of a four-vector proportional to

or more explicitly

These equations apply to classical fields, e.g. one component of the electromagnetic vector potential, as well as to wave functions in particle quantum mechanics.

As an example let us therefore consider the Klein-Gordon wave function.

Setting

we write

yielding with

The Hamiltonian.

In order to establish a link with classical mechanics, we first conceive the space coordinates

Considering the classical expression of the Hamiltonian

with the canonical variable

we have the correspondence

defining the canonical variable

With these definitions we obtain for the classical relation (2.18) the following equivalent expression:

Switching now to the limit of continuous space coordinates, this result takes the form

where

with

Let us consider as an example the Klein-Gordon case.

According to Equation (2.16) the Lagrange density can be written as

We then have

Second quantization.

Simply speaking, a given wave function is quantized if it is replaced by an operator. This is familiar in quantum electrodynamics where e.g. one component of the vector potential is replaced by photon creation and annihilation operators. A similar procedure can be applied to quantum mechanical wave functions and in this latter case one then talks of second quantization, since the wave functions are already obtained by a first quantization procedure. Note however that the term second quantization is not universally accepted.

Here we consider again as an example the Klein-Gordon case, which constitutes the simplest one, as it concerns spinless particles like K or π mesons.

Let us first switch from

The Hamiltonian density then takes the form

Since we want to quantize the system by replacing wave functions with operators in the Schrödinger picture, we disregard

Integrating over the space coordinates, we thus arrive at the following expression for the Hamiltonian in terms of functions in

with

To obtain Equation (2.29) we have made use of the relation

The parenthesis inside the integral of Equation (2.29) reminds one of the Hamiltonian

of a harmonic oscillator.

In the latter case quantization is achieved by introducing creation and destruction operators

with the commutator

We therefore try in Equation (2.29) the substitutions

The parenthesis inside the integral in Equation (2.29) is then found to be given by the expression

Since complete summation over

We thus obtain for the Hamiltonian the following result

According to general rules of quantum physics, the commutation relation for canonical variables takes the following form in the present case:

Inserting into the commutator the transformation relations given By equation’s (2.27a), (2.27c) we write

Substituting for

Adopting the trial rule

Equation (2.35) reduces to

Substituting this result into Equation (2.34) we recover the commutation relation of Equation (2.33). This confirms the validity of the trial rule of Equation (2.36).

In the field equations developed above the number of particles concerned is not specified. Let us now be more specific by introducing single particle states

The second term on the r.h.s. of this equation contains the infinite quantity

In order to establish the time dependence of the operators

Starting from the expressions (2.31a), (2.31b) we evaluate the corresponding Heisenberg operators of

Acting on an eigenstate

using

Similarly we have

Hence the requested operator equations are

With Equation (2.31b) the quantized form of Equation (2.27a) becomes

where Equation’s (2.39a), (2.39b) have been used.

Introducing the Lorentz invariant scalar product

Causality again.

As mentioned earlier, two points

Starting from Equation (2.41) the commutator is given by the expression

where the operator commutation rule of Equation (2.36) has been used. In order to obtain zero for this quantity, the inversion transformation

Now we define a space like surface [3]

Without loss of generality we can restrict ourselves to the plane

Now take a particular point

One then has the relations

Figure 1. Transformation diagram for space like coordinates in connection with the causality proof discussion. The quantities

Hence the transformed quantities are

yielding the following result in terms of rotated quantities:

Now the cumbersome factor

Inside the light cone, i.e. for time like separations, the commutator does not vanish so that in this region points can be causally connected. It is however interesting to note that the corresponding commutator is invariant with respect to proper Lorentz transformations as shown e.g. in ref. [1] .

Note finally, that in many calculations the infinite energy of the vacuum state is eliminated by performing normal ordering of operators. It consists in reshuffling operator products in such a way that destruction operators always stand on the right of creation operators.

Generalizations [4] [5] [6] .

Particles obeying the Klein-Gordon equation do not bear any electric charges. In order to treat charged particles, complex wave functions have to be introduced into the theory. Even more profound modifications are necessary in the case of electrons according to the Dirac theory. Here, due to the presence of spin, wave functions are represented by spinors consisting of four functions as components of a vector. An even more striking difference occurs if second quantization is performed. In this case, the fermion character of the particle is taken into account in postulating anti-commutation rules for the field operators instead of the commutation rules pertaining to bosons.

However, the general idea of avoiding negative energy states by means of second quantization, already applied to the Klein-Gordon case, remains essentially the same in this and other situations.

3. Symmetry Transformation Relations

An essential feature of relativistic particles and fields is their behaviour with respect to transformations of the Lorentz group.

Transformation operators

We recall that the elements of this group are three rotations in the xy, xz, and yz planes around the z, y and x axis respectively, completed by three pseudo-rotations belonging to the xt, yt and zt planes respectively. These transformations can be viewed as an infinite succession of infinitesimally small rotations which generate a representation of the group. Designating the rotation operator with respect to the plane

yielding for the finite Lorentz transformation operator the expression

Recalling that the familiar expression for rotations in ordinary space can be generalized to Minkowski space as

we can generate a four dimensional representation of the proper Lorentz group by acting with this operator on the vector

we consider the example

This matrix thus corresponds to a rotation by an infinitesimal angle

As a second example we consider the Lorentz boost in the

with

Note that the factor

of Equation’s (3.5) and (3.7) by the column vector

relations for the corresponding infinitesimal rotations and Lorentz boosts.

Applying a Lorentz transformation as expressed by the operator

The criterion for the corresponding wave equations to be valid is their Lorentz invariance. This property can be established by proving that the Lagrange density, from which a given wave equation is derived, is a Lorentz scalar. We shall now demonstrate this point in the particular case of the Klein-Gordon equation.

We cast the Lagrange density of Equation (2.16) in the form

with only one type of differential operator. With the transformation of Equation (3.8), i.e.

the scalar property of

where we have omitted on the r.h.s. the argument

According to Equation’s (3.1) and (3.2) we write

With the defining relation

Treating only the change introduced by the transformation and given the fact that

In the first term the indices

whereas for the second term we find with

Hence the final result

Suppose now that

The proof given here for infinitesimal variations is generally valid, since finite transformations involve an infinite succession of infinitesimal ones. As already mentioned, more formal proofs are found in the literature, but we thought it instructive to approach the problem by explicit calculations as well.

Spinors.

Having treated as an example the case of a structure less particle obeying the Klein-Gordon equation, we are now moving to the case of the electron, where in addition to space coordinates spin variables have to be considered, together with the existence of an electric charge.

Introducing spin functions

Considering components

where the functions

Its Lorentz transformation can be expressed as follows:

where it is understood that the operator

We now define operator matrix elements

with

We now recall that spin functions transform under rotations in ordinary space according to the Pauli spin matrices

Then clearly, ordinary space rotations occur according to the relation

i j k in normal order.

Remark: normal order means that i j k are all different and that starting with 1 2 3 an odd number of permutations introduces a minus sign. One may ensure this property automatically by multiplying with a quantity known as the

The question now arises, what happens in the case of Lorentz boosts? Without entering into details, we only state the answer given by Dirac’s theory according to the relation

Hence the matrices of Equation’s (3.21) and (3.22) constitute a four-dimen- sional representation of the Lorentz group known as the Dirac-Pauli representation.

The Weyl representation.

The Dirac-Pauli representation is reducible since its matrices can be brought into diagonal form by a unitary transformation involving the matrices

With these matrices we have

and hence

whereas the

Designating as left and right handed spinors

Taking as an example the values

showing that the functions

Clearly, these relations can be generalized for arbitrary rotation and boost parameters described by vectors

Hence the Weyl spinors

In order to explain the designations of

spinors.

As an example the spinors introduced in Section 4 are right handed for those of Equation’s (4.13a), (4.15a) and left handed for those of Equation’s (4.13b), (4.15b). This can be shown by applying the helicity operator with

Connection with wave equations.

The wave equation for spinors

as the corresponding Euler-Lagrange equation applied to

Note that for

The

where the + index indicates an anticommutator. Note that later in this text the anticommutator will be designated by the symbol

Given the fact that the matrices

Making the guess that

one obtains the result

By setting

one then obtains the following relations:

The Dirac equation, given in its general form by Equation (3.29), then takes in the case of the Weyl representation the form of the following two coupled equations:

written in matrix form as

As can be seen from these equations, the mixing of the two Lorentz group representations

Noether currents.

Let us now consider some continuous symmetry transformations on the wave functions, which leave the Lagrangian density invariant. In the infinitesimal limit we then write

The corresponding change in the Lagrange density

With the obvious relation

we then have

Using the identity

the second term on the r.h.s. of Equation (3.41) can be rewritten with the result

Now the second term of this equation, set equal to zero, represents the Euler-Lagrange equation as given by Equation (3.14). For

Introducing Noether currents by the defining relation

Equation (2.43) involves the four-divergence of this quantity for which we thus have

Integrating this expression over the entire ordinary space, and applying Gauss’ theorem to the corresponding three-divergence, with vanishing contribution at the infinite surface, we are left with the expression

Hence the space integral

In order to interpret this quantity, let us consider the Dirac equation. The corresponding Lagrange density function is given by Equation (3.28). This equation is invariant under the phase transformation

For Noether’s current we then have, according to Equation (3.44)

and

where we have used the fact that in any representation

4. The Dirac Field

As an entrance door to the Dirac field let us consider free particle solutions of the Dirac Equation (3.29). These solutions can be viewed as superpositions of plane waves of the form

Plugging this expression into Equation (3.29), yields the equation

This equation is most easily solved in the rest frame, where only the component

where for

Introducing two-component spinors

where the factor

Let us now look for a more general solution with two components

This solution can be obtained by performing a Lorentz boost on the previous one, which in infinitesimal form can be written as

This relation can be deduced by analogy from the matrix of Equation (3.7) noticing that all spatial directions are equivalent whereas the infinitesimal parameter

For finite values of

The second expression on the r.h.s. is obtained by expanding the exponential

and noticing that even powers of the matrix

whereas odd ones leave this matrix unchanged.

Now we apply the same boost to the amplitude

From the infinitesimal operator as given by Equation (3.24) with I = 3, we deduce the relevant Lorentz transformation operator

Considering the matrix

power of the matrix in the exponent of Equation (4.9) yields the unit matrix, whereas an odd one yields this same matrix. The series expansion of the exponential operator of Equation (4.9) therefore leads to the following matrix expression:

Explicitating

where the relation

has been used.

We now go back to Equation (4.8) and calculate the amplitude

special spinors

positive and negative

So far we have put the minus sign on the exponent of the defining relation given by Equation (4.1). Consider now the case of a plus sign with

We choose however to maintain

We are not repeating a calculation similar to the previous one, but indicate only the relations replacing Equation’s (4.13a), (4.13b). For these special situations one finds

Defining as usual

With

A similar calculation for the case of Equation (4.15b) yields the result

For the case of an arbitrary spin orientation axis we introduce the notations

Furthermore we have the relations

The Hamiltonian.

Starting from the expression (3.28) of the Lagrangian density

and from the expression of the conjugate variable

density is given, according to Equation (2.23) by the expression

More explicitly we then have with

In the expression of

Involving the single particle Hamiltonian

The amplitudes

remembering that

This equation can be expressed in the form

Replacing

Introducing these expressions into Equation (4.25) yields the eigenvalue relations stated above

with

Second quantization.

In replacing the wave function

or equivalently

Defining an empty state

Introducing the total Hamiltonian

After substituting the expression (4.29) and its adjoint we write

Inverting the order of integration, we take advantage of the relation

and notice that, according to Equation (4.20), the cross terms in the product of the integrand in Equation (4.31) disappear. We are thus left with the expression

where, given the integration over all values of

Eliminating the amplitudes by means of the relations (4.18), (4.19), we thus arrive at the final expression

At this stage it has to be reminded that in the present case of fermions the operators obey anti-commutation relations, which in contrast to the boson relations (2.37), are of the form

This relation allows us to deal with the embarrassing negative energy term in the integrand of Equation (4.33).

Writing by means of the rule stated by Equation (4.34)

we have cast the negative energy into an infinite constant term which can be ignored if the origin of the energy scale is shifted adequately.

A next step consists in interchanging the order of

Normal ordering

A procedure of eliminating negative energy terms in the Hamiltonian consists in what is called normal ordering. It means that all operator products are reshuffled in such a way that annihilation operators stand always on the right of creation operators. These operations are symbolically expressed by the letter

Applying this convention to the expression (4.22), supposed second quantized, we thus write

where

Here the time dependence of the operators has been absorbed into the exponential factors. Moreover, the interchange

A calculation similar to that developed above, with only the cross terms contributing, then leads to the expression

This is exactly the result obtained previously if in Equation (4.35) the infinite negative energy term is ignored and if the operator and state changes discussed there, are accomplished. Thus clearly normal ordering merely integrates these facts.

5. Propagators

The retarded Green’s function.

Let us first consider propagation amplitudes given by the expressions

These expressions are obtained by using the fact that in the product of the wave functions of Equation’s (4.37a), (4.37b) only cross terms contribute. This is because in the other terms annihilation operators are on the right and therefore eliminate these terms in the mean values of Equation’s (5.1a), (5.1b). Furthermore the operator relation (4.34) has been accounted for.

We now evaluate the spin sums appearing in Equation’s (5.1a), (5.1b). Using Equation’s (4.13a), (4.13b) and (4.15a), (4.15b) we obtain the following tensor products:

where the relation

A similar calculation yields

For the spin sum we therefore arrive at the result

It is now an easy matter to show that this matrix is identical with the expression

with after a similar calculation

Making these replacements in the expressions (5.1a), (5.1b) and adding them afterwards, we obtain an anticommutator of the form

with

We now want to link the above commutator to an integral in four space. For this purpose we introduce a quantity defined by the relation

where

for

for the lower clockwise circuit, corresponding to

whereas for the upper circuit, corresponding to

Inserting the value given by Equation (5.7) into the complete integral given by Equation (5.6) we can, without loss of generality, replace in the second term

and for

Comparing with Equation (5.4) we thus find

where

Figure 2. (a) Complex integration path for evaluating the integral of Equation (5.6) in the Green’s function case. (b) Similarly in the Feynman’s case.

Going back to Equation (5.6) we notice that the denominator

Written in the form

this quantity can be regarded as the Fourier transform of

or in Feynman slash notation

This expression is known as the Dirac propagator. Its Fourier transform represented by Equation (5.10) is a Green’s function of the Dirac operator defined in Equation (3.29). To see this, we first notice that for plane wave states this operator can be written as

thus proving the Green’s function relation stated above.

Note however that the integral in Equation (5.10) can be evaluated along different paths. The way chosen so far yields the particular expression (5.9), called the retarded Green’s function. This is because it is only non zero during the time period

The Feynman propagator.

A different path for evaluating the integral of Equation (5.6) is that shown on Figure 2(b). Designating by

Inserting these expressions into Equation (5.6) we obtain the Feynman Green’s function

where again in the second line

Comparing these expressions with Equation (5.4) we see that we have

This can also be written as

where

In the Feynman case the integration paths can be slightly modified with respect to those of Figure 2(b) if we replace Equation (5.10) by the expression

With the denominator equal to

away from the real axis to

of the integration paths.

Interpreting Equation (5.18) as a Fourier integral we thus obtain for the Feynman propagator the expression

or in slash notation

These expressions are basic elements in Many-Body type calculations.

The photon propagator.

In analogy with Equation’s (5.16) and (5.17) representing the Feynman propagator in the Dirac case, we define a photon propagator by the relations

Corresponding to the time-ordered product

Here

The quantities

Postulating the rule

This expression reduces to

with

The value of the quantity

As in the Dirac case we now link the expression (5.25) to an integral in 4 dimensional space of the following form:

Performing the integration over

Comparing this with Equation (5.20) we see that the two integrals correspond to the expressions defining the propagator

Setting

as the final result for the photon propagator in the Lorentz-Feynman gauge.

6. Interacting Fields: The Radiative Electron Mass Shift

Introduction.

Consider an electron in the form of a point charge-e, then the surrounding static electric field possesses the energy

with

out this treatise we use natural units setting

In order to make the integral in Equation (6.1) finite, a lower cut-off radius

In this way the energy tends linearly towards infinity with the cut-off parameter

Attempts have been made to improve things by applying the formalism of quantum field theory to this problem. In this treatise we present a slightly renewed version of these calculations. As a result the linear divergence of the semi-classical theory is brought to the form of a logarithmic one however with no quantitative solution at the end.

The propagators.

Preliminary remark: as is customary in quantum field theory we designate vectors and indices in 4 dimensional Minkowski space by ordinary letters and l.c. greek letters (e.g.

We now consider an electron moving freely through vacuum and define a correlation function by the expression

where

In expression (6.3) the Dyson operator

The presence of ground states

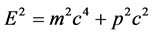

The easiest way for evaluating the correlation function (6.3) consists in applying Feynman rules according to the Feynman diagram of the figure (Figure 3) which shows that the electron-vacuum interaction can be conceived as the emission and reabsorption of a virtual photon visualized by the wavy line.

The elements of this diagram correspond to Feynman propagators in momentum space given by the expressions

Figure 3. Feynman diagram for evaluating the electron correlation function of Equation (6.3).

for the electron of mass m in momentum state p and k respectively and the propagator expression

for the photon.

In this way during the process the total momentum of the system is conserved at every step. In addition the expressions

describing the electron-photon interaction have to be inserted at the vertices.

In these expressions the Feynman slash notation abbreviates the sums

Assembling these relations, known as the Feynman rules, we see that the above diagram corresponds to the product

where the relation

where the central part is given by the expression

after adding an integration over all possible intermediate 4 momenta.

The index on

The integration procedure.

Before starting the integration in the expression for

Comparing with Equation (6.9) we thus write the

Following a common procedure we now change variables according to the relation

Then the parenthesis in the denominator of the integrand takes the form

An essential simplification arises if we restrict ourselves to the zero’th order contribution in

The integral in (6.10) then reduces to

Note that the same letter

Separating the

where now all matrices are replaced by scalars.

The evaluation of the second integral is presented in Appendix leading to the result

Setting

Introducing the dimensionless variable

with the limiting expression

where we have assumed that the cut-off value

Plugging this result into Equation (6.9) we thus arrive at the final expression

Renormalization.

Let us suppose that the change in the correlation function represented by the resulting expression (6.19) can be reproduced by renormalizing the mass in the free electron propagator, i.e. by adding a correction

Equating the correction term with the expression (6.8) with the expression (6.19) for

Approximating on the r.h.s.

This is the result derived in the literature by various methods, showing that the fully quantized theory reduces the linear convergence of the classical expression (6.2) to a logarithmic one.

Discussion.

There seems to be no indication how to estimate the cut-off parameter

a number that seems realistic. Naturally this estimation has to be taken merely as an example among others that one could imagine.

However, despite the fact that the true numerical value of the electromagnetic electron mass shift is as yet unknown, its correct qualitative evaluation, as reviewed in this section undoubtedly constitutes an important fact.

Zitterbewegung

The fact that quantum field calculations lead to a logarithmic divergence of the electron self-energy instead of the linear classical result of Equation (6.2), can be understood if one takes into account the spread of the electron position due to quantum fluctuations [7] . This is equivalent with attributing the electron a finite dimension of the order of the Compton wavelength

In order to determine the position

Interpreting the central part

as a density operator we obtain the desired average by taking a trace represented fomally by the expression

Writing out explicitly the product of (6.23) we obtain from the defining relation (5.14) the result

under the condition

Furthermore, the variable

The taking of the trace in Equation (6.24a) amounts to integrating over the variable y and afterwards replacing the matrix

The integral of Equation (6.27) is elementary, yielding with

With the last integral on the r.h.s being equal to

probability the final result

As a test we integrate over the entire space and find

thus proving the validity of our probability calculation.

Clearly a distribution as represented by Equation (6.29) will lead to a softer divergence than one of the type

7. The Electron-Electron Scattering (M

Consider scattering involving two particles and introduce a scattering matrix in the form

where the second term describes the scattering process.

Assuming that the particles have incident momenta

where

We specialize now to the case of two colliding electrons schematically represented by the Feynman diagram below.

We write the Hamiltonian of the system in the form

where

with

The relevant contribution here is the second order term in the perturbation expansion of the

Given the interaction Hamiltonian of Equation (7.4) this term contains the time-ordered product

with T the familiar time ordering operator. Note that a factor 1/2 from the exponential expansion is left out since it is compensated for by adding identical expressions with

Substituting into the parenthesis the expressions derived in section (3) for

At this stage we suppress for simplicity spin labels on the operators and functions.

Putting in the expression (7.7) the operators in normal order we make the replacement

We now take matrix elements between states

Together with the preceding sequence of Equation (7.8) this generates the new operator sequence

We now make use of operator commutation relations which yield the equations

similarly for

Now after integrating in Equation (7.7) over the variables

Going back to Equation (7.6) and recalling that the contraction of vector potential operators is equivalent with the propagator expression

we obtain the matrix element in the form

Identifying the

Comparing this expression with the defining relation (7.2) we find for the electron-electron scattering amplitude the formal expression

The non-relativistic limit.

In the non relativistic limit where it is assumed that the kinetic energy of the electrons is small as compared to

with

Then for

with

The products in Equation (7.16) are

Furthermore we have in this approximation with

Thus the amplitude of Equation (7.16) reduces to

Now clearly, labeling the spins by

Consider now the electrostatic potential

In the case of a Coulomb potential

An elementary integration yields the result

Comparing this result with Equation (7.22) one sees that the amplitude factor

For the sake of completeness we indicate the link between the amplitude

Substituting for

Note that this expression is equal to the celebrated Rutherford formula which applies to scattering of a particle in a static Coulomb field.

The Yukawa potential.

An approach similar to that leading to the Coulomb potential, treated in terms of the exchange of a photon between two electrons, has been proposed by Yukawa in 1935 for the interpretation of nuclear forces. Here the interaction takes place between heavy particles of mass

The calculation can be deduced from the previous one by replacing the photon

propagator by the meson propagator

of the meson and the electro-magnetic interaction

In the non-relativistic limit one finds

Connecting in this limit the scattering amplitude to the potential

with in the

Setting

This attractive potential is short ranged as compared with the Coulomb potential. The presence of the exponential factor yields for this range the value

Although the Yukawa model has been replaced since by more evolved concepts, it still provides insight into the nature of nuclear forces.

8. Vacuum Polarization

The photon self energy.

Consider a photon propagating freely in vacuum. If its interaction with the vacuum field is taken into account, a situation represented by the Feynman diagram below will be present. During the propagation there will be emission/absorption of a virtual electron/positron pair at one vertex and afterwards the inverse process will occur at the other vertex.

The difference with respect to the case without interaction involves a tensor which in second order will be written as

Applying, as in the electron case, the Feynman trick and setting afterwards

one arrives at the expression

where terms linear in

In [1] a Wick rotation has been applied to this integral with the result

with

This integral is ultraviolet diverging. It can be simplified by using the tensorial relation

involving the scalar quantity

Assuming now

For the integral on the r.h.s. we have, according to [1] , the expression

The remaining integral is logarithmically ultraviolet diverging. Let us calculate it however formally as follows:

Pauli-Villars regularization.

The Pauli-Villars regularization consists in making the integral convergent by subtracting the same expression but with

The integral of Equation (8.9) thus becomes

For the quantity of interest we therefore find

Considering

with

Charge renormalization.

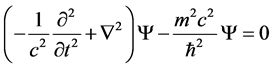

Going back to the electron-electron scattering problem clearly the photon self-energy effect just discussed, will manifest itself as a modification of the photon propagator represented by the wavy line in Figure 4, which therefore has to be replaced by the configuration of Figure 5. One then expects that the global effect corresponds to the scalar quantity

The amended Coulomb potential

Having treated the diverging expression in (8.7) by means of a regularization procedure, we are now going to extract from this expression a term which is independent of any cut-off parameter. For this purpose we make the following first order expansion:

where we have set

Figure 4. Feynman diagram for electron-electron scattering.

Figure 5. Feynman diagram representing the creation of a virtual electron/positron pair during photon propagation.

assuming

where the equivalence

Expliciting now

With the values of the integrals equal respectively to

find

which is indeed the value found in the literature.

Atomic energy level shift

Consider now the Coulomb potential as given in

Taking the inverse Fourier transform yields for the amended potential in

Applying this potential to electrons inside an atom will lead to a shift of energy levels obtained by multiplying the correction term with the electron density function and space integration. The effect then becomes proportional to

For numerical values of the expected or measured shifts we are referring to the abundant literature on this subject.

9. Conclusion

In this treatise we are interested in phenomena involving the presence of what is sometimes called the physical vacuum. To deal with these effects, one adopts the field viewpoint, which consists of replacing for elementary particles, e.g. electrons, wave functions by operators acting on physical vacuum states. Interactions between fields defined in this way are then treated according to Feynman’s propagator method. The main difficulty affecting this method is the appearance of divergencies which are dealt with by means of two specific procedures known as regularization and renormalization. The first one consists of making expressions finite by applying e.g. cut-off or Pauli-Villars regularization. The second one is a redefinition of physical quantities, e.g. electric charge or mass, in accordance with the finite results previously obtained. In this treatise, we consider mainly results for the electron self-energy and the vacuum polarization case. Some of our derivations of these results are original and special attention is given to their interpretation in terms of the underlying physical facts.

Acknowledgements

Particular thanks go to Prof. Gillian Peach and to Prof. Cynthia Kolb Whitney for reading and improving the manuscript.

Cite this paper

Schuller, F., Neumann-Spallart, M. and Savalle, R. (2017) Guidelines to Quantum Field Interactions in Vacuum. Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 382-424. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.83026

References

- 1. Peskin, M.E. and Schroeder, D.V. (1995) An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory. Advanced Book Program Westview Press Boulder, Colorado.

- 2. Erdé lyi, A. (1954) Tables of Integral Transforms. Vol. 1, McGraw-Hill, New York, p. 75.

- 3. Erdé lyi, A. (1953) Higher Transcendental Functions. Vol. 2, McGraw-Hill, New York, p. 23.

- 4. Mandl, F. and Shaw, G. (2010) Quantum Field Theory. 2nd Edition, Wiley, Chichester.

- 5. Bjorken, J.D. and Drell, S.D. (1965) Relativistic Quantum Fields. McGraw-Hill, New York, St. Louis, San Francisco, Toronto, London, Sydney.

- 6. Weinberg, S. (2010) The Quantum Theory of Fields. Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 7. Milonni, P.W. (1994) The Quantum Vacuum. Academic Press, St. Diego, New York, Boston, London, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto.

- 8. Sakurai, J.J. (1967) Advanced Quantum Mechanics. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

- 9. Glauber, R., Rarita, W. and Schwed, P. (1960) Physical Review, 120, 609.

https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.120.609

Appendix

Evaluation of the integral

Setting

With the change of variables

The integral in (A2) takes the form

where we have deliberately not specified the integration limits.

Introducing the identity

we ignore the principal value which in a more detailed treatment can be proven to yield zero. With the delta function inserted the expression (A4) then reduces to

Performing the derivation as indicated in Equation (A2) and replacing the intermediate parameter A by its value leads to the desired result