Applied Mathematics

Vol.07 No.03(2016), Article ID:64029,17 pages

10.4236/am.2016.73023

Non-Detection Probability of a Diffusing Target by a Stationary Searcher in a Large Region

Hongyun Wang1, Hong Zhou2*

1Department of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, Baskin School of Engineering University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, USA

2Department of Applied Mathematics, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, USA

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 30 December 2015; accepted 26 February 2016; published 29 February 2016

ABSTRACT

We revisit one of the classical search problems in which a diffusing target encounters a stationary searcher. Under the condition that the searcher’s detection region is much smaller than the search region in which the target roams diffusively, we carry out an asymptotic analysis to derive the decay rate of the non-detection probability. We consider two different geometries of the search region: a disk and a square, respectively. We construct a unified asymptotic expression valid for both of these two cases. The unified asymptotic expression shows that the decay rate of the non- detection probability, to the leading order, is proportional to the diffusion constant, is inversely proportional to the search region, and is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the ratio of the search region to the searcher’s detection region. Furthermore, the second term in the unified asymptotic expansion indicates that the decay rate of the non-detection probability for a square region is slightly smaller than that for a disk region of the same area. We also demonstrate that the asymptotic results are in good agreement with numerical solutions.

Keywords:

Detection of a Random Target, Asymptotic Solutions, Decay of the Non-Detection Probability

1. Introduction

Searching is a common activity in our everyday life. For example, we look for lost car keys in a big parking lot, search for hidden natural resources such as oil and metals in a vast field, and search for missing people in a national park; the U.S. Coast Guards conduct thousands of open ocean search and rescue missions every year; the police hunts for drug smugglers; the military searches for Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and insur- gents in Iraq and Afghanistan. More examples can be found in Koopman’s classical book [1] and in a recent article by Beckhusen [2] .

Historically, the search for enemy submarines during World War II stimulated intensive scientific studies, giving rise to a branch of operations research now known as search theory [3] - [9] . The continued importance of finding maritime targets as well as other hidden objects keeps providing new research challenges in the field.

In search theory, we call the object being sought the target. The search region is the region that both the target and the searcher are confined to. Generally speaking, search problems can be loosely divided into two cate- gories: one-sided search and two-sided search. In one-sided search, the searcher tries to detect the target while the target does not know the presence of the searcher, i.e., the target does not try to avoid the searcher in any active way. In two-sided search, the target has some capability of sensing the presence or the approaching of the searcher and may design a way to avoid being detected by the searcher. In one-sided search, the main objective is to maximize the probability of detection in a given time period and/or to minimize the cost or time of the search for a given tolerance of the non-detection probability. One-sided search can be further characterized by the constraints placed on the searcher’s actions and the target motion. This includes stationary target problems and moving target problems. Different approaches have been taken to address these problems. For example, Stone [8] derived necessary and sufficient conditions for optimal detection problems. Mangel [10] calculated joint probability density for target location and unsuccessful search by the ray method. Mangel also formulated the search and mining problems as constrained optimization problems and then solved the problems by vari- ational techniques [11] . Washburn [12] found the searcher path that minimized the mean time to locate a random stationary target where the starting point could be chosen by the searcher. Eagle and his co-workers found a searcher path that maximized the probability of detecting a moving target in a fixed time duration [13] - [15] . Washburn [16] compared several branch-and-bound methods for solving a moving-target search problem. Dell and collaborators applied an optimal branch-and-bound procedure to find a feasible path that maximized the probability of detecting a moving target using multiple searchers with constrained path [17] . MacPhee and Jordan considered the optimal search problem for a leprechaun that moves randomly between two sites and the movement was modeled with a two-state Markov chain [18] . Majumdar and Bray calculated the survival pro- bability of a tracer particle moving along a deterministic trajectory in the presence of diffusing traps [19] . Fernando and Sritharan computed the non-detection probability of infinitely many diffusing Brownian targets by a moving searcher which traveled along a deterministic path with constant speed in the two-dimensional plane [20] . Wang and Zhou conducted numerical studies to calculate the non-detection probability of a randomly moving target by a stationary or moving searcher in a square search region [21] . They also considered the search problem where a target moves between a hiding area and an operating area via multiple pathways where the searchers are equipped with either cookie-cutter sensors [22] or stochastically intermittent sensors [23] . In con- trast, the two-sided search problem is traditionally addressed by formulating the problem as a game-theory problem [24] [25] . It involves a searcher and a target who knows that it is being chased and attempts to avoid detection or capture. Early work on search games was presented in the classic book of Shmuel Gal [26] . This monograph mainly addresses the problem of finding optimal search trajectories in order to locate a target. Recent developments on the theory of search games and rendezvous are discussed in the books [27] [28] . More references on the two-sided search problem can be found in the review paper by Chung, Hollinger and Isler [5] .

One of the classical one-sided search problems involves a lone searcher looking for a single moving target. A classical mathematical problem is to examine the non-detection probability of a diffusing target by a stationary sensor such as fixed acoustic sensors, sonobuoys, or possibly mines. This problem has been investigated by Eagle [29] . A diffusion equation is used to describe the probability density of a diffusing target (modeled as a Brownian particle). When the search region is a disk and the cookie cutter detector (a detector whose detection region is a circle of a given radius) is fixed at the center of the search region, analytical solution to the boundary value problem can be formulated using separation of variables. The solution by separation of variables contains an infinite sum of Bessel functions. For large time, the solution is well approximated by the slowest decaying mode. For a rectangular search region, analytical solutions are still unknown. Instead Eagle carried out Monte Carlo simulations and numerically estimated the probability of non-detection.

In this paper we revisit this classical problem of detecting a moving target by a stationary sensor or searcher. We first nondimensionalize the problem, then we derive asymptotic approximations to the decay rate of the non-detection probability of a diffusing target by a fixed searcher in a large detection region for two different geometries of the search region: a disk and a square, respectively. For the disk-shaped search region, we show that the asymptotic solution agrees very well with an accurate numerical solution obtained by solving an algebraic equation involving Bessel functions. For a square search region, asymptotic solutions show that the decay rate of the non-detection probability is slightly smaller than that for a disk search region of the same area. Finally, we combine the two cases into a unified form by expressing the decay rate of non-detection probability in terms of a large parameter: the ratio of the search region to the searcher’s detection region. The significance of our results lies in the simple and explicit asymptotic expressions of the decay rate of the non-detection pro- bability. It shows that the decay rate of the non-detection probability, to the leading order, is inversely propor- tional to the logarithm of the ratio of the search region to the searcher’s detection region.

2. Mathematical Formulations

Consider a search region A of “characteristic” radius . For a disk, the characteristic radius

. For a disk, the characteristic radius  is the true radius; for a square, the characteristic radius

is the true radius; for a square, the characteristic radius  could be half the width, for example. Suppose the searcher is capable of detecting target within distance R. That is, the searcher covers a disk of radius R centered at the location of the searcher, which is called the detection region of the searcher. Once the target gets inside the detection region, it is detected instantaneously. This is the so-called cookie-cutter sensor/searcher in search theory. In this paper we study two cases: a disk search region and a square search region.

could be half the width, for example. Suppose the searcher is capable of detecting target within distance R. That is, the searcher covers a disk of radius R centered at the location of the searcher, which is called the detection region of the searcher. Once the target gets inside the detection region, it is detected instantaneously. This is the so-called cookie-cutter sensor/searcher in search theory. In this paper we study two cases: a disk search region and a square search region.

We consider the situation where the searcher is fixed at  and the target moves randomly with a diffusion coefficient D, confined in region A (the search region). Let

and the target moves randomly with a diffusion coefficient D, confined in region A (the search region). Let  be the probability of the target being at position

be the probability of the target being at position  at time t.

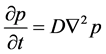

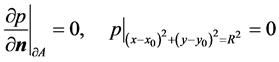

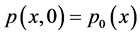

at time t.  is governed by the diffusion equation with boundary and initial conditions:

is governed by the diffusion equation with boundary and initial conditions:

(1)

(1)

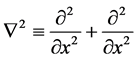

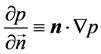

where  denotes the Laplace operator and

denotes the Laplace operator and  represents the directional derivative of

represents the directional derivative of

p along the normal vector  of

of  (the boundary of search region A). Of the two boundary conditions, the first one corresponds to the reflecting condition at the boundary of the search region A, and the second one refers to the absorbing condition at the boundary of the searcher’s detection region.

(the boundary of search region A). Of the two boundary conditions, the first one corresponds to the reflecting condition at the boundary of the search region A, and the second one refers to the absorbing condition at the boundary of the searcher’s detection region.

The objective of this paper is to seek asymptotic solutions when the detection radius R of the searcher is much smaller than the characteristic radius  of the search region A. Mathematically, that is

of the search region A. Mathematically, that is

The function

After non-dimensionalization, the characteristic radius of the search region is 1 and the detection radius of the searcher is

3. Asymptotic Solutions

The initial boundary value problem (2), in principle, can be solved using the method of separation of variables. More specifically, the solution can be expressed as

where

In the expression of

Let

That is, over long time, the decay rate of the survival or non-detection probability is given by the smallest eigenvalue

3.1. Search in a Disk Region

We consider a disk-shaped search region as illustrated in Figure 1. After non-dimensionalization the search region A is a unit disk. The searcher is fixed at the center of the disk

In (Muskat, 1934), it is shown that

Figure 1. A schematic illustration of a diffusing target in a disk search region of radius

where

To derive an asymptotic solution, we view the right-hand side of (7) as a source term and recast the equation for

where

When

・ probability flows out at the absorbing boundary and gets added back in as the source term

・ the source term

・ the probability outflow (detection by the searcher) is slow;

・ the relaxation within the region is relatively fast.

From these observations, it follows that as long as the total amount of the source term

We use a delta function at

A general solution of Equation (10) is

The probability out-flow at the absorbing boundary is

In the calculations above, we have ignored terms smaller than

Note that

Specifically, in Equation (9), we set

multiple of an eigenfunction is still an eigenfunction. Equation (9) with boundary conditions becomes

A particular solution of Equation (13) is

Enforcing the boundary conditions

where

In the calculations above, we have neglected terms smaller than

With the new approximation of

constant multiple of an eigenfunction is still an eigenfunction. We set

and we pick

For each term on the right-hand side of (16), we find a corresponding particular solution. A particular solution of

Determining coefficients

We now have 3 approximations for eigenfunction

Based on the most recently updated

Figure 2. Three asymptotic solutions and an accurate numerical solution for eigenfunction

probability out-flow at the absorbing boundary and the total amount of the source term. In this new round of improvement iteration, we expect to get the coefficient of

where

asymptotic results for the normalized decay rate of non-detection probability,

Going back to the physical quantities before non-dimensionalization, we conclude that, over long time, the decay rate of non-detection probability for a disk search region has the asymptotic expression:

where

3.2. Search in a Square Region

Next we study the case of a square search region as shown in Figure 4. The search region A after non-dimen- sionalization is a square of width 2. The searcher is at the center of the square,

Even though the search region is not axisymmetric, we will not completely abandon the polar coordinates

For a square of size 2 centered at

Figure 3. Comparison of 3 asymptotic expansions and the accurate numerical solution for the normalized decay rate of non-detection probability as a function of

Figure 4. Detecting a diffusing target in a square region by a stationary searcher.

We use a similar approach as we did in the case of a disk region. We treat the right-hand side as a source term and view

where

・ probability flows out at the absorbing boundary and gets added back in as the source term

・ the input of probability from the source term

・ in contrast, the relaxation of probability distribution within the region is relatively fast (fast time scale).

Due to the separation of slow and fast time scales, the exact distribution of the source term, to the leading order, will not affect solution

The exact solution of (23) is given by

The probability out-flow at the absorbing boundary is

where function

Geometrically, when we look at the intersection of the circle of radius r and the square,

Equating the out-flow and the source term, we have an expression of

where

Note that

approximate differential equation for

we choose

Figure 5. Geometric meaning of function

Both the differential equation and the absorbing boundary are still axisymmetric. When the reflecting condition at the square boundary is put away, the system allows axisymmetric solutions. We first solve for an axisymmetric solution of this system and then we use superposition to take care of the reflecting condition at the

boundary of the square. A particular axisymmetric solution of (29) is

general axisymmetric solution of (29) with the absorbing boundary condition can be written as

where

Note that in the general solution, both coefficients

is the coefficient of

For each of

of an integer multiple of

is zero if and only if the integral over one side of the square is zero. Specifically, in step 1 for

Substituting (31) into (33), we obtain

In step 2 for

The last condition

This property plays an important role in the calculation of

This quantity is also important in the calculation of

Next, we enforce the reflecting boundary condition for solution

Using Equation (38) to determine coefficient

In step 2 for

Similar to the situation for

The exact expression of

Putting all components together, the solution of (29) with both the absorbing boundary condition and the reflecting boundary condition is approximately

where functions

As before,

source term

where the coefficients

The 2-term asymptotic expansion of

where

We like to find the accuracy of the asymptotic solutions we derived above for a square search region. Unfortunately, for a square search region, no analytical or semi-analytical solution is known yet. A very accurate numerical solution is also difficult to compute. The circular cookie-cutter detector is incompatible with the square search region in a numerical discretization. It is difficult to design a numerical grid to accommodate both the square outer boundary and the circular inner boundary. Instead, we use Monte Carlo simulations to compute the decay rate of non-detection probability density.

To gauge the accuracy of Monte Carlo simulations, we first carry out Monte Carlo simulations in the case of a disk search region for which a very accurate numerical solution is known. Figure 6 compares the Monte Carlo solution for a disk search region and the very accurate numerical solution obtained by solving an algebraic equation involving Bessel functions. In Figure 6, each point is based on a Monte Carlo simulation of 100,000 particles integrated over more than 40 million time steps. Each time step (

In the case of a square search region, we use the Monte Carlo solution as the accurate solution and we compare it with the two asymptotic expansions. Figure 7 shows that the asymptotic solutions have good agreement with the accurate Monte Carlo solution when

In terms of the physical quantities before non-dimensionalization, we conclude that over long time, the decay rate of non-detection probability for a square search region has the asymptotic expression:

Figure 6. Comparison of Monte Carlo solution and the very accurate numerical solution in the case of a disk search region. Each point in Monte Carlo solution is based on a simulation of 100,000 particles integrated over more than 40 million time steps. The error shown is the difference between the Monte Carlo solution and the very accurate numerical solution. The results demonstrate that the Monte Carlo solution has adequate accuracy. In the case of a square search region, we will use the Monte Carlo solution to validate the asymptotic expansion.

Figure 7. Comparison of two asymptotic expansions and the accurate Monte Carlo solution in the case of a square search region.

where

3.3. A unified Form

Finally, we compare the results of the two cases that we have analyzed so far. We define the large parameter as the ratio of the area of search region A (disk or square) to the searcher’s detection area:

Since we only have a two-term expansion for a square search region, in the comparison we will use only two terms from the asymptotic expansion for a disk search region. We write the results of these two cases in a unified form:

where the shape factor

Note that in the unified form (50), the normalized decay rate is defined slightly differently from the one used in the discussion of a disk or a square search region. In the discussion of case 1 and case 2, we used

In summary, for both a disk search region and a square search region, the decay rate of the survival probability, to the leading order, is proportional to the diffusion constant, is inversely proportional to the search area, and is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the ratio of the search area to the searcher’s detection area. Furthermore, the second term in the asymptotic expansion implies that the decay rate of the non-detection probability for a square region is slightly smaller than that for a disk region of the same area.

4. Concluding Remarks

We have derived asymptotic expressions for the decay rate of non-detection probability of a diffusing target in the presence of a stationary searcher in a large disk or square search region. The asymptotic expansions agree well with a very accurate numerical result obtained by solving an algebraic equation involving Bessel functions in the case of a disk search region. In the case of a square search region, the asymptotic expansions are validated by comparing them with an accurate result computed in large scale Monte Carlo simulations. Based on the asymptotic expansions obtained, respectively, for a disk and for a square, we write out a unified asymptotic expression valid for both of these two cases, in which the effect of the area of the search region is separated from the effect of the shape of the search region. The unified asymptotic expression shows that the decay rate of non-detection probability, to the leading order, is proportional to the diffusion constant, is inversely proportional to the search area, and is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the ratio of the search area to the searcher’s detection area. The leading term is not affected by the shape of the search region provided that the area of the search region is kept unchanged. The second term in the unified asymptotic expansion is affected by the shape of the search region. It indicates that the decay rate of non-detection probability for a square region is slightly smaller than that for a disk region of the same area.

Acknowledgements

Hong Zhou would like to thank Professor James Eagle, Professor Jim Scrofani and Professor Sivaguru Sritharan for helpful discussions.

Cite this paper

HongyunWang,HongZhou, (2016) Non-Detection Probability of a Diffusing Target by a Stationary Searcher in a Large Region. Applied Mathematics,07,250-266. doi: 10.4236/am.2016.73023

References

- 1. Koopman, B.O. (1999) Search and Screening: General Principles with Historical Applications. The Military Operations Research Society, Inc., Alexandria, Virgina.

- 2. Beckhusen, R. (2013) Search Theory and Big Data: Applying the Math That Sank the U-Boats to Today’s Intel Problems.

http://www.defensenews.com/article/20130705/C4ISR02/307050013/Search-theory-big-data-Applying-math-sank-U-boats-today-s-intel-problems - 3. Benkoski, S.J., Monticino, M.G. and Weisinger, J.R. (1991) A Survey of the Search Theory Literature. Naval Research Logistics, 38, 469-494.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6750(199108)38:4<469::AID-NAV3220380404>3.0.CO;2-E - 4. Chudnovsky, D.V. and Chudnovsky, G.V. (1989) Search Theory: Some Recent Developments. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York.

- 5. Chung, T.H., Hollinger, G.A. and Isler, V. (2011) Search and Pursuit-Evasion in Mobile Robotics: A Survey. Auton Robot, 31, 299-316.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10514-011-9241-4 - 6. Dobbie, J.M. (1968) A Survey of Search Theory. Operations Research, 16, 525-537.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.16.3.525 - 7. Stone, L.D. (1989) Theory of Optimal Search. 2nd Edition, Academic Press, San Diego.

- 8. Stone, L.D. (1989) What’s Happened in Search Theory Since the 1975 Lanchester Prize? Operations Research, 37, 501-506.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.37.3.501 - 9. Washburn, A.R. (2002) Search and Detection. Topics in Operations Research Series. 4th Edition, Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences, Linthicum, MD.

- 10. Mangel, M. (1981) Search for a Randomly Moving Object. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics, 40, 327-338.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/0140028 - 11. Mangel, M. (1981) Optimal Search for and Mining of Under Water Mineral Resources. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics, 43, 99-106.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/0143008 - 12. Washburn, A.R. (1995) Dynamic Programming and the Backpacker’s Linear Search Problem. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 60, 357-365.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0377-0427(94)00038-3 - 13. Eagle, J.N. (1984) The Optimal Search for a Moving Target When the Search Path Is Constrained. Operations Research, 22, 1107-1115.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.32.5.1107 - 14. Eagle, J.N. and Yee, J.R. (1990) An Optimal Branch-and-Bound Procedure for the Constrained Path, Moving Target Search Problem. Operations Research, 38, 110-114.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.38.1.110 - 15. Thomas, L.C. and Eagle, J.N. (1995) Criteria and Approximate Methods for Path-Constrained Moving-Target Search Problems. Naval Research Logistics, 42, 27-38.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6750(199502)42:1<27::AID-NAV3220420105>3.0.CO;2-H - 16. Washburn, A.R. (1998) Branch and Bound Methods for a Search Problem. Naval Research Logistics, 45, 243-257.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6750(199804)45:3<243::AID-NAV1>3.0.CO;2-7 - 17. Dell, R.F., Eagle, J.N., Martins, G.H.A. and Santos, A.G. (1996) Using Multiple-Searchers in Constrained-Path, Moving-Target Search Problems. Naval Research Logistics, 43, 463-480.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6750(199606)43:4<463::AID-NAV1>3.0.CO;2-5 - 18. MacPhee, I.M. and Jordan, B.P. (1995) Optimal Search for a Moving Target. Probability in the Engineering and Informational Sciences, 9, 159-182.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0269964800003764 - 19. Majumdar, S.N. and Bray, A.J. (2003) Survival Probability of a Ballistic Tracer Particle in the Presence of Diffusing traps. Physical Review E, 68, Article ID: 045101(R).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.68.045101 - 20. Fernando, P.W. and Sritharan, S.S. (2014) Non-Detection Probability of Diffusing Targets in the Presence of a Moving Searcher. Communications on Stochastic Analysis, 8, 191-203.

- 21. Wang, H. and Zhou, H. (2015) Computational Studies on Detecting a Diffusing Target in a Square Region by a Stationary or Moving Searcher. American Journal of Operations Research, 5, 47-68.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajor.2015.52005 - 22. Wang, H. and Zhou, H. (2015) Searching for a Target Traveling between a Hiding Area and an Operating Area over Multiple Routes. American Journal of Operations Research, 5, 258-273.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajor.2015.54020 - 23. Wang, H. and Zhou, H. (2016) Performance of Stochastically Intermittent Sensors in Detecting a Target Traveling between Two Areas. American Journal of Operations Research, in Press.

- 24. Eagle, J.N. and Washburn, A.R. (1991) Cumulative Search-Evasion Games, Naval Research Logistics, 38, 495-510.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6750(199108)38:4<495::AID-NAV3220380405>3.0.CO;2-6 - 25. Thomas, L.C. and Washburn, A.R. (1991) Dynamic Search Games. Operations Research, 39, 415-422.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.39.3.415 - 26. Gal, S. (1980) Search Games. Academic Press, New York.

- 27. Alpern, S. and Gal, S. (2003) The Theory of Search Games and Rendezvous. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston.

- 28. Alpern, S., Fokkink, R., Gasieniec, L., Lindelauf, R. and Subrahmanian, V.S. (2013) Search Theory: A Game Theoretic Perspective. Springer, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6825-7 - 29. Eagle, J.N. (1987) Estimating the Probability of a Diffusing Target Encountering a Stationary Sensor. Naval Research Logistics, 34, 43-51.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6750(198702)34:1<43::AID-NAV3220340105>3.0.CO;2-6

NOTES

*The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.