Sociology Mind

Vol.4 No.2(2014), Article ID:45487,14 pages DOI:10.4236/sm.2014.42019

The Spirit of Motivational Interviewing as an Apparatus of Governmentality. An Analysis of Reading Materials Used in the Training of Substance Abuse Clinicians

Tony Carton

School of Health and Wellbeing, Wellington Institute of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

Email: tony.carton@weltec.ac.nz

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 11 December 2013; revised 21 January 2014; accepted 19 February 2014

ABSTRACT

Substance abuse clinicians working at the coal face with clients daily are confronted with client problems that are robust and tangible. The understanding of these problems is granted epistemological and ontological legitimacy by the psy-sciences. As a result, practice in the substance abuse treatment and addiction fields are rarely subject to the scrutiny provided by post-structural analysis. Moreover, the disciplines of addiction treatment and sociology rarely collaborate in any meaningful way for numerous reasons. For the AoD clinician caught betwixt and between biological psychological and sociological discourses, there has been a tendency to opt for the perceived problem solving capabilities of psychological discourses. However, in a post-aetiological hemisphere, attention is increasingly fixated on the fiscal imperative. Clinician/Client relationships have been reconfigured in neo-liberal society. In this study, materials used to train undergraduate students Motivational Interviewing skills in an Alcohol and Drug degree programme were subject to a textual analysis deploying the Foucaultian concept of governmentality. The familiar aetiological descriptor model used in the field was transposed into the Foucaultian term discourse. One article subject to analysis is presented here. The intention was to interrogate the effects of Motivational Interviewing on client and clinician and the resultant repositioning. It was found that Motivational Interviewing technologies reposition the client as an active self-governing autonomous subject while the clinician is professionally and spiritually imprecated in the manufacture of a neo liberal subjectivity within the client. It is argued that the client/clinician interaction constituted, owes less to clinical considerations than to contemporary neo liberal agendas. Proponents of the practice cite progressive and enlightened facets of Motivational Interviewing through an uncritical indebtedness to ascendant resilience and strength based discourses. Alternatively it can be understood as an individualising strategy that displaces clients from former robust communities of understanding, latterly positioned as primitive or deficit ridden. In the resulting motif cli- ent/clinician interaction is reconfigured so that the active rational, self-empowered client is produced by the newly embourgoised clinician. Clinical concerns are casually jettisoned. Thus Motivational Interviewing is at once a political/apolitical apparatus, which requires further interrogation.

Keywords:Substance Abuse; Addiction; Motivational Interviewing; Foucaultian; Governmentality; Neo-Liberalism; Professionalization

1. Introduction

For numerous reasons, the alcohol and other drug (AoD) treatment field and the science of sociology rarely collaborate. The paradox that “addiction is an individual behaviour that has a social effect” (Adrian, 2003: p. 1388) is part of the issue. In the domain of social policy, there has been interdisciplinary collaboration but this is often beyond the purview of most AoD clinicians and not within the ambit of this article. The sciences of psychology with their advancement of the modern individual self, have appealed as more relevant. The addict has been viewed as the quintessential defected individual self existentially flawed, culpable in their own demise.

Interestingly, this virulent construction, of the defected self, so poignant in the public domain in the professional discourse, has disappeared in the field with the arrival of what are known as strength based approaches. However, historically myriad psychological etiologies had arisen conspiring in varying methodologies recommending how to correct the flawed individual. Indeed the process of proposing etiologies, hitherto so popular, resulted in localized passions given the contestations habituated in the AoD field. In recent history, there has been a privileging of the maligned, yet useful disease model (Reinarman, 2005), properly (though rarely) understood as a metaphor. This has been anathema to sociological sensitivities and written off as “disease-ist”. An inability of the sociological sciences to countenance the possibility that addicted individuals do exist is cited by Room (Adrian, 2003) referring to the under-inflation of real human suffering caused by wholesale sociological deconstruction. The Twelve Step disease model is based on the empiricism of human experience of powerlessness over a substance, submission to this fact and a subsequent dialectic of achieving sobriety by acceptance. This dynamic would be more understandable within religious concepts rather than modernism. The cognitive, that entity so cherished in modernity is within Twelve Steps theory, a problematic construct, not always to be trusted. Indeed Freud, Marx and Nietzsche problematized the same entity which after all is a long standing problematic in the Judeo Christian tradition. However, in sociological theory, the Cartesian subject remains a fundamental rubric. In this way, sociology joins with Motivational Interviewing in a mythology that states all is understandable by the application of rational logic.

Sociology has received limited credibility in the addiction field. Merton (Adrian, 2003), deploying a structural functionalist position, attempted to place addiction on a sociological footing receiving some credibility within the field. However, often overlooked is Cohen’s apt overarching descriptor of drug users and indeed dealers. “Our society as presently structured will continue to generate problems for its members … and then condemn whatever solutions these groups find” (Cohen, 2002: p. 104). The author has a long standing belief that the science of sociology provides the most coherent understanding of addiction, despite the fact that this is not recognized.

The intention of this research was to demonstrate how practices in the substance abuse treatment field have become enrolled into a neo-liberal agenda. Although this is not unique in the caring professions, the addiction field presents more concerns that are brought into sharp relief because of a persistent sizeable minority who find asylum in alternative epistemologies that provide a veracity of localized evidential truth. Remaining within the discipline is an access to a robust peer vocabulary not yet obliterated as is the case of other disciplines. Through professionalization and the tertiary education process, this is often subdued by a hidden curriculum yet it still continues. The difficulty is that engaging with this voice has recourse to metaphors that have not yet met respectability in the psychological or sociological fields. The author feels the need to ask for a provisional suspension of disbelief while these epistemological coordinates lack legitimacy.

1.1. Review of Traditional Practices

Before considering Motivational Interviewing and its implications it is worthwhile to review traditional practices in the substance abuse field. In New Zealand over the majority of the twentieth century, as in most western countries residential methods of treatment had predominated for those who were known as addicts and alcoholics. These publicly funded centres were heavily influenced by the Twelve Step model, based on achieving a goal of total abstinence.

The Twelve Step movement is a peer based organization which borrowed the disease term from the dispositional model (Chaudron, 1988) thereby removing culpability from the sufferer, and appending a spiritual component borrowed from all the major religions. Twelve Step philosophies became the epistemological precursor for many of the practices in these centers. Treatment centers also utilized deep Freudian psychodynamic/confessional practices and latterly Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Treatment was long term, intense and intrusive, sometimes up to a year. Assessment for the programmes was based on binary assessment criteria. A person was either an alcoholic/addict or not. Clinically for therapists their role was clear, to delve into the unconscious, unearthing the root of the affliction and removing it. Supporting the patient/client was an etiology based hypothesis surrounding the efficacy of catharsis as a source of healing. Drama and epiphany was a daily occurrence. Often heavy confrontation was employed as a tactic, and all this was state funded in centres such as Queen Mary Hospital in Hanmer Springs, Aspel House in Plimmerton, and the Salvation Army Bridge Programme at Rotoroa Island.

However, not unlike other parts of the mental health sector, there was a movement from service provision in the hospital to the community. Supporting this movement, various clinical apparatuses evolved under the ambit of brief intervention. One of these is Motivational Interviewing.

1.2. Emergence of Strength Ideology

The practices described above were based on common sense linearity. It was thought that certain individuals possessed a defect, the cause of this was surmised and a subsequent cure process ensued. Within this epistemological landscape the conditions of possibility to imagine or indeed critique deficit practices were not present. Now, however an asymmetry can be resolved and we are presented with the possibility to critique strength based practices.

1.3. Motivational Interviewing

Motivational Interviewing is a practice based on brief intervention frameworks. For numerous reasons it has received wide acclaim in the alcohol and drug field. Its proponents make the claim that it is strength based Miller & Rollnick (2013). Although commandeering many of the techniques of older practices it is radically different. One difference is that it is not specifically targeted at individuals who are addicted, now referred to by the DSMIV as “dependent” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000: p. 192). It was originally targeted at those who are problematic, thus by definition not dependent, although the practice is used with dependent clients as well.

Motivational Interviewing has become widespread practice in New Zealand and elsewhere in the substance abuse treatment field. Emanating from brief intervention frameworks, it has achieved wide acclaim along with some critique within psychological circles (Joseph et al., 1999, Burke et al., 2003) but minimal attention from alternative paradigms, such as post-structural or sociological standpoints and even less from those which can address the political effects of this truncation.

Although the practice commandeers many traditional techniques, it is qualitatively different. Most significantly is that it is claimed to be strength based (Manthey et al., 2011). It consists of interviews rather than counselling and utilizes what are known as broad strategies. These may include discussing the client’s typical day and how their drug use fits in, asking the good and less good things of using drugs and providing the client with information on the effects of drugs (Miller & Rollnick, 2013: p. 142). The aim is to evoke from the client what is known as “change talk”. For example the client may say “I think I may have a problem”. To the uninitiated it would appear that these practices are eminently useful, and they are to a degree, but they rely on the client as being an ideal type far removed from the traditionally viewed diseased individual who is powerless over the substance.

1.4. Historical Models or Genealogy

Common sense reviews of addiction understandings drawing on modernist assumptions often portray a history comprising a linearity ranging from ancient times until today. This linearity would propose a trajectory with models acting as metaphysical essential ciphers proposing cause, problem and the intervention as well as the professional helper required. The models reflect social conditions. Table 1 illustrates how historical models proposed the original causes that needed attention when addiction was presented as a problem.

The moral model proposed the cause as being an individual moral impediment, a culpable failure to obey moral sanctions that had been ordained by God. In a given context, especially when auguring in the industrial revolution, this made sense seemingly endorsed and reinforced by the sinful and culpable activities of the inebriated individual or masses presenting to the workhouses under the gaze of the evangelical outraged. The appropriate intervention required the expertise of the minister or priest advocating prayer in order to instill the ascendant virtues of willpower and self-control. Crucially these virtues were appropriate to the emerging new capitalist relationships of production.

The dispositional model, on the other hand, posited the problem as ordained by science as a biological and/or genetic flaw within the diseased individual with an inborn susceptibility that overrode all capacities for the newly privileged concept known as willpower. Although these emerging models augmented, and at times collided, they had ascendant commonalities. They addressed the concept of the individual subject which was flawed and needing correction.

A wild card, however, was introduced in 1935 in the US in the form of the Twelve Step movement. Notoriously anti-intellectual and anti-expert (Valverde, 1999) it commandeered and manipulated earlier discourses to address the culpability/susceptibility debate May (1997). Despite its peer and non-professional base, or maybe because of it, this movement for many won the debate, certainly among the sufferers and it became the privileged etiology.

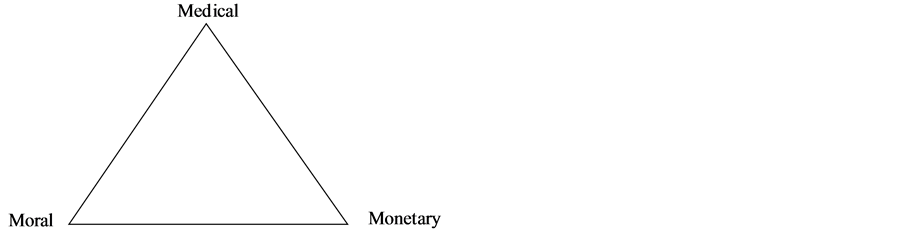

Addiction etiologies and their consequent models explaining human behaviour were envisaged as passive conduits of an essential truth ordained by God but increasingly authorized by science. Inevitably, they were based on an unchallenged concept of a fixed self within the individual who was intrinsically flawed morally, biologically or spiritually, thus needing correction. Recent models emanating from within the similar individualizing regime of modernity again cite the flawed individual. Now bad, now sad, and now mad, these models provided the strategies intended to remake the individual into a worthy member of the modern state. However, interventions of varying degrees were intense and long term, and became progressively depicted as expensive in the later twentieth century as the remorseless fiscal imperative reached ascendancy. This was all within a modern episteme bounded by a pervasive triangulation of morality, medicine and monetarism.

The diagram below (Figure 1) illustrates the modern understanding of addiction/substance abuse as it is bounded by this triangulation. This episteme does not refer to ancient understandings of addiction, nor is it part of an elegant teleology of ancient understandings. It is strongly grounded in modernity and capitalism.

Table 1. Traditional understanding throughout the ages.

Adapted from Chaudron (1988).

Figure 1. Triangulation of addiction understandings.

Different vertices of the triangle (moral, medical and monetary) alternatively collide, collude and reinforce each other at different times, but the paradigm does not alter.

1.5. Moral

This is often seen as the old model and refers to values of self-control and sobriety in all senses of the word. Under this regime drunkenness was seen to be a habit of individuals who were culpable sinners. These sinners were urged to exercise willpower. Lack of willpower was seen as a moral failure.

1.6. Medical

With the rise of science and the displacement of God, alcoholism began to also attract the medical gaze. Under this regime, it was considered a disease. In some ways, it opposed the moral model, by removing culpability from the agenda and replacing it with susceptibility and individual inability to control drinking.

1.7. Monetary

All of these understandings of addiction were embedded in the new capitalist system throughout the western world. This discourse has progressed under neo-liberalism to be now the most potent.

A common sense review of addiction understandings would cite an unbroken teleology of understandings from its origins to something that has progressed from time immemorial. The diagram above cites more of a genealogy of addiction and places the current episteme which is one that edits our thought and passion and the way we talk about addiction.

1.8. Models or Discourses?

The elegant modernist cause and effect relationship, proposed by etiological based models, in a neo-liberal context is rendered obsolete. This is not due to inherent flaws within their reasoning nor evidence of lack of efficacy, but because of an insidious fiscal imperative. Attention to causation, as a guide to action, fascinating as it is and convincingly relevant is expensive as Todd (2001) states “etiology is of limited importance” (p. 3). Furthermore through the process of professionalization the AoD worker has become steadily embourgoised, the client-clinician relationship reconfigured. The clinician role is no more to probe deeply for cause and consequent cure, to teach the skills needed to function in life, nor to mentor into the paths of morality. Rather it is to provide strategies of self-management to the client, as clinicians become consultants on regimes of self-care. Simultaneously there is the rising narrative of strength based approaches, talk of disease or symptomology deleted and resilience placed at an individual level as part of an active intrinsic self. The substance abusing client (now referred to as a consumer) is constituted no longer as a deficient individual but now no different to a client presenting to a real estate agent or a solicitor in the realms of the new quazi market.

Post-structural approaches deploying the insights of Foucault would attend not to a history, but a genealogy of addiction. This would have three effects. Firstly a genealogy would reveal the fragmented, contingent and arbitrariness of addiction understandings. Secondly it would address the constitutive importance of discourses. Thirdly it would enable us to collapse time in order to critique our own practice away from our own peculiar history. Post-structural discourse analysis “involves a critique of metaphysics of the concepts of causality, of identity, of the subject of power knowledge and of truth” (Zeeman et al., 2002: p. 97). In a post-structural analysis, truths are deconstructed away from immanence towards being negotiable, fragile, and contingent thereby subject to decommissioning. Crucially, discourse analysts take the position that what is descriptive is also prescriptive, sometimes indeed proscriptive. Truth then is not an entity or essence but is a product of an asymmetrical social consensus regarding the way we talk about things, including ourselves.

Genealogy of addiction etiologies have been cited back to the English Land Enclosure Acts, Industrial Revolution the rise of Capitalism and Modernity (May, 1997; Reinarman, 2005). Ushered in with these eras were a myriad of seemingly unrelated discourses of science, medicine, hard work, sobriety and prudence which inevitably incited themselves into our morality. This continues in the current paradigm of late modernity whereby discourses of morality, medicine and monetarism conspire to make addiction and its treatment thinkable.

A key insight provided by Foucaultian theory is the productivity of discourses. The descriptor discourse radically apprehends the constitutive effects of what are traditionally known as models, often envisaged as merely descriptive (Thombs, 1999). Models may have moral, medical, dispositional, Twelve Step or cognitive underpinnings. More recently there have been psychodynamic, psychological and cultural models. Some models overlap and some contradict, giving rise to alliances and tensions. A post-structural analysis, moving away from this thin description, would transpose the term models with discourse and would speculate that discourses not merely reflect but produce. They produce the assemblages of how we think, feel and act with regard to certain entities which by talking of them we reify. What were known as etiologies compete less as ciphers of an essential truth but more as contingencies in a casuistic marketplace where attention to therapeutic consideration is increasingly marginalized. On the ground floor, these productions are enacted at the micro-level through the utilization of clinical technologies. Viewed in this light, the AoD clinician no longer facilitates a catharsis liberating a repressed subjectivity, nor do they act as mentor or peer. They act as a conduit of subjectivity production within accessible regimes of power that performs dialectically to reify an imbedded reality. This reality is inevitably conducive to incarnation in a neo-liberal society.

This study moves away from the familiar psychological terrain of reporting the effectiveness of treatment to the ethical question of the effects of treatment, in order to address the political impact of practices, and to describe how these are facilitated by AoD workers on a micro level through various technologies. Post-structural analysis provides the means to consider the constitutive effects of historical models and practices. A governmental analysis provides a means of illuminating how in this regard Motivational Interviewing is constitutive, in a qualitatively different manner from older practices, it being more conducive to a neo-liberal landscape. In effect AoD workers clinicians unknowingly become agents of subjectivity creation appropriate for the retraction of the state, the pursuit of governing at a distance (Dean, 1999) through self-government.

2. Research Method

The qualitative research analyzed units of text, namely written artifacts used in the training and practice of motivational interviewing. For the purposes of this article, one particular text was analyzed (Bell 1997), which was a comparison of Motivational Interviewing with other practices.

2.1. Samples

Training materials in a “book of readings” used in the teaching of skills to student clinicians were analyzed. These are used as reading materials for the degree module of Motivational Interviewing in order to teach counsellors in the alcohol and drug field at degree, diploma and certificate level. Each reading was textually analyzed independently.

The readings are written with the appearance of academic rigor, read as teaching and sometimes clinical, texts usually by mature students entering the alcohol and drug treatment field, though often by long time practitioners now required to obtain professional qualifications.

The module was taught at three major city campuses and various offsite Marae-based sites for Maori students. The student body is generally predominately middle aged. Often up to half the students are in recovery having incurred alcohol or drug problems in their lives or in their families.

2.2. Textual Analysis

A textual analysis was applied to training materials indicated above.

This method was used to interrogate training and practice texts in order to assess their potential/possible effect. Texts were analyzed “not as what they say, but what they do” (Zeeman et al., 2002: p. 100) highlighting “tricks” dependent on relevant discourses. Utilizing the work of Silverman (2005) several questions guided the analysis.

1. How are they written?

2. How are they read?

3. Who reads them?

4. For what purposes?

5. What is recorded?

6. What is omitted?

7. What is taken for granted?

8. What assumptions are made?

Questions 1 to 5 above describe how the texts work in a given environment. Questions 6 to 8 provide a pathway to explaining how texts were effective in the given context.

Each article was given a serial number from 001 to 026. Additionally for the readings each line was numbered from 001 through to the end.

2.3. The AoD Field

It is useful at this point to contextualize idiosyncrasies of the AoD field. This field lacks the professional acclaim and esteem of associated disciplines such as nursing, psychology or social work. Substance abuse clients who come in contact with professionals from these disciplines often report that they find them naïve patronizing, at best aloof even “stupid”. Up until fairly recently the field was predominantly staffed by individuals with personal or family experience of addiction or abuse often being members of Alcoholics Anonymous or other Twelve Step movements. Affective and traditional knowledge were thus considered more valuable and practical than the possession of academic or professional prowess. Significant to state also has been the reported tension between proponents of abstinence and harm reduction (Todd, 2001). This issue of etiology and models is often interpolated as a commitment to a model as a matter of passion.

2.4. Researcher Position

The researcher is a lecturer in the degree course, with a long term role as an alcohol and drug clinician and teaching Motivational Interviewing along with other therapeutic practices such as Client Centered Practice (CCP) and CBT as well as theory papers in sociology, addiction theory and clinical practice. The researcher is not the course leader and did not have a role in decisions of the content of students’ book of readings. The researcher, however, makes no claim to objectivity and this is appropriate to the methodology of discourse analysis. The researcher is not a member of any Twelve Step movement, but readily identifies himself with a Marxist perspective.

Over a period of two years, the researcher has taught the Motivational Interviewing module many times. This teaching included tutoring, co-marking practical demonstrations and marking essays of self-critique.

3. Findings

It was found that the articles described above, bearing a manifestation of objectivity, achieved their effects through emotional resonances. Older discourses that dwelt on the niceties of etiology were marginalized by the ascendancy of neo-liberal discourses. These discourses served in constructing the client as resilient and the clinician as hyper skilled. The clinician-client relationship was radically reconfigured from the traditional sick role/helper of Parsons the customer consumer/provider relationship of the marketplace.

A crucial omission in the texts was that of etiology, being parked but potent in its absence. Alternative frameworks of discussion were jettisoned away from etiology towards discourses of professionalism and management. Several assumptions and taken for granted truths were commandeered regarding the context of the readers. These were attached to the emotional investment involved with these local etiologies.

A simple comparison is presented between various recent practices. Alcohol and other drug students being inculcated into values of rationality and evidence based ideologies would likely surmise these statements as possessing an ultimate, prosaic truth. However, despite appearances of objectivity, the writers deploy literary artifices enticing the situated reader into the text. Although value judgments are ostensibly prohibited in Motivational Interviewing in this post-etiology, post-ethical hemisphere, they reappear like Banquo’s ghost albeit under a different guise appropriate to a neo-liberal context.

3.1. Textual Devices

Omissions and assumptions acted to entice the reader into the text emotionally. Given the context, wedged between older models, alleged in these texts to be judgmental and unskilled, the new free liberal yet asymmetrical practice of Motivational Interviewing appeared, in sharp relief, to be built on principles of strengths and thereby professionalism. The seeming academic appearances of the text belie an asymmetry that enlists an emotional response.

It was found that several literary devices were utilized that drew on situated tensions in the AoD field. These devices included.

3.2. Binary Oppositions (BO)

This is a Foucaultian concept (Foucault, 1978) juxtaposing dichotomous practices in a hierarchy, creating a dramatic effect, acting in this case to privilege MI, subjecting traditional practices to a process of othering.

3.3. Ideal Types (IT)

This is borrowed loosely from Weber denoting a social item (Giddens, 2002). Here it denotes stereotypical caricatures and situations. Deploying ideal types creates drama by mobilizing sympathy or disdain, in this case disdain against older practices thereby veneration for newer practices.

3.4. Analysis

This is shown in tables of comparisons of MI with previous practices utilized in the recent history of the AoD field. Each column is headed by a descriptor of a specific practice: Motivational Interviewing (MI), Confrontation of Denial (CD), Skills Training (ST), and Nondirective Approaches (ND). The intention is to compare Motivational Interviewing with the modalities in the other columns. With the focus being on MI there is no comparison between the other modalities. CD for instance is not compared with ST or ND. Due to this centrality of MI and these omissions, MI impresses the reader with its stability despite being a relative newcomer. Sustaining this, the title Motivational Interviewing is explicit. But what is incorporated by the depictions Confrontation of Denial (CD), Skills Training (ST) and Non Directive (ND) is unclear. This omission is significant in that it would rely on assumptions regarding the reader’s knowledge base, in effect drawing them into the text.

3.5. Confrontation of Denial versus Motivational Interviewing

Confrontation of denial (CD) refers to the AA Twelve Step model, albeit an ideal type caricature of the practice. A common resource deployed by competing professionals is the ideal type “recovering counsellor” lacking qualifications and sophistication who indulges in deeply confrontational practices, often cited for his/her “attitude” and perceived “insistence on abstinence and confrontation rather than harm reduction and motivation” (Todd, 2001: p. 21). (L8). With the rise of professionalization AoD workers are required to acquire academic and professional qualifications. Comparatively recently a recovering history was almost the sole requirement for entry into the field. A key part of the professionalization and tertiary education is the hidden (Bowles & Gintis, 1976) and the encouragement to abandon older peer wisdoms.

Much of the text relies on the impact of dichotomies familiar within the AoD field (Thombs, 1999). These are identified in bold. Binary oppositions (BO) are textually mobilized to affect this. Words like exploring (1) eliciting (5) are counter-poised with correcting (1) convincing (5) to dramatic effect. Words such as explore, elicit and reflection (7) appeal to a softer progressive yet neo-liberal agenda. They contrast with primitive authoritarian terms such as correct, convince and argument.

3.6. Positioning of Client (CD versus MI)

The new client (Table 2) under MI is reproduced as an individual, eminently rational and responsible. A process of exploration, as opposed to strong confrontation, will elicit rational responses known as “change talk” (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The ideal type designer consumer as opposed to the old diseased client possesses rationality sufficient to facilitate change in the use of intoxicating substances, through the “development of discrepancy” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013: p. 243) within the balanced self. This relegates older deficit discourses of powerlessness, such as disease of addiction (3) being helpless (1T) advancing Cartesian discourses of the supremacy of rationality producing a client eminently in control (4). In MI the client, in changing, actively engages in practices of self-care active and collaborates with the clinician freely mobilizing discourses of economy, self-control and individualism. Importantly the client is active in their own self-care and responds like an eminently rational consumer.

Table 2. Confrontation of denial versus motivational interviewing.

3.7. Positioning of Clinician (CD versus MI)

Binaried dramatically against nonprofessional clinician with inappropriate attitudes (Todd, 2001), the MI practitioner is subsequently highly professionalized, skilled, non-judgmental, and progressive in accessing various apparatuses of authority provided by the new profession. Being skilled not given to labeling, acting seamlessly as consultants in the rhetoric of self-care. The nexus of power produces clinicians that inhabit common sense discourses of rationality, science, yet increasingly fiscal considerations. As these discourses rendered as scientific are utilized, judging or moralizing practices are ostensibly deleted. A client-clinician relationship built on a radical freedom is envisaged. However, this freedom is the site of asymmetry wherein the clinician is the expert in certain technologies. The client ostensibly entitled to accept or reject this freedom. The client who does not want to change is not corrected or labelled as being in denial, not argued with or judged. They are termed as pre-contemplative (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) and effectively off the radar.

3.8. Skills Training versus Motivational Interviewing

Once again it is not explicit what Skills Training (ST) refers to, so the reader is invited into the text. The assumption would be that it refers to Cognitive Behavioral Approaches. In these practices, it is hypothesized that substance abuse/use is learned and can therefore be unlearned through the client developing certain skills. This indicates the need for clinicians who take a teaching and coaching role.

When MI is compared with ST the terms like elicits (12) and, explores (11) are counterpoised with prescribes (12) and taught (14) as binaries (BO).

3.9. Positioning of Client (ST versus MI)

The idea of motivation which is activity in self-care, is advanced as a naturally occurring phenomenon (Table 3). Against this is posited the idea of problem-solving strategies being taught (14). MI does not pathologize clients because of their maladaptive cognitions (11). The natural/taught dichotomy suggests the client has an innate ability to know even pre-teaching and therefore is accomplished enough to readily source this knowledge.

3.10. Positioning of Clinician (ST versus MI)

The clinician under the MI practice is constructed as one who moves back from the role of teaching to one who facilitates self-care in the client. The newly professionalized and highly skilled clinician elicits (12) as opposed to prescribe (12). Thus the client is free to decide, yet the clinician skillfully directs this freedom. There is therefore no requirement for the clinician to teach or mentor.

Table 3. C skills training versus motivational interviewing.

3.11. Non-Directive Approaches versus Motivational Interviewing

Non-directive approaches (ND) refer to Freudian models and psychodynamic approaches which translate into what is known as Client Centered Practice (CCP). It owes its origins to the work of Carl Rogers who challenged the power of medico-psychiatric models. Freudian psychology and psychodynamic theory posits that certain feelings are denied “so that the addict becomes more dependent on their external environment, (that is alcohol and drugs) for the satiation of their psychic needs” (Thombs, 1999: p. 98). Some proponents of CCP take an essentialist view of counselling. The counsellor must not be directive (Gilberd, D. & Gilberd, K., 2001) but must be present in the role as a neutral person in order for the client to come up with their own solutions. In theory, the counsellor does nothing but listen, albeit in a skilled way, so that the depths of the troubled soul can be accessed to achieve cathartic release.

With regard to ND and MI comparisons, systematically directs (15) counterpoises with allows (15), and offers (16) counterpoises with avoids (16).

3.12. Positioning of Client (ND versus MI)

The client (Table 4) is positioned here as an essentially rational, reasonable individual, intrinsically capable of overriding feelings of hurt and shame with the aid of a consultant in matters of change. Indeed from its antideficit vantage point MI regards any unpleasant feelings no matter how debilitating as an opportunity, a state of ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) and a precursor to change, a business opportunity.

3.13. Positioning of Clinician (ND versus MI)

Under MI, compared to ND, the clinician is positioned as a much more skilled and indeed economic practitioner, in terms of resources and emotion. The MI therapist works selectively (18) and contingently (18) searching out opportunities to increase, create and amplify motivation. MI is above all a brief intervention. The binary opposition (BO) operating here mobilizes the ideal types (IT) such as the highly skilled MI practitioner and the bumbling, uneconomic, nondirective clinician.

Motivational Interviewing practices thus construct the client as being totally responsible and rational, the therapist as involved in this construction. This is at variance to older practices which preached disease.

4. Discussion

A New Zealand writer has commented “While neo-liberalism may mean less government. It does not follow that there is less governance” (Larner, 2000: p. 11).

The Foucaultian term “governmentality” (Foucault, 1978, 1988) morphs the concepts government and mentality describing the state of self-governance endemic in a neo-liberal society. Through various endeavors understood genealogically, the western social democratic state has instilled virtues of rationality, economy and latterly empowerment through apparatuses provided by the psy-sciences (Rose, 1999). These virtues were enacted through government funded Social Welfare, Education, Health Care, Mental Health and more recently Alcohol and Drug professionals, with the goal of constituting the individual as a productive member of society. Invariably these sciences emanated from deficit based etiologies that prescribed pathology and thereby solutions. But

Table 4. Non-directive approaches versus motivational interviewing.

they also contained inherently several contradictions. Paradoxically practices that are associated with what has been disparaging known as the overbearing nanny state have been commandeered into apparatuses that have been transformed into strategies of disengagement and retraction of the welfare state. This is not to claim any degree of intentionality but is a by-product of these internal contradictions.

4.1. Reconfiguring the Clinician-Clinician Relationship

Innocent reams of paper along with allied apparatuses served to construct/reconstruct a new contingent reality. Significant was a vitriolic reconfiguring of the clinician/client relationship. These were abetted by inferences and omissions, the appropriation of ideal types such as the recovering judgmental counsellor, the over-bearing cognitive therapist and the flaky bumbling psychotherapist. Binaried against these were the non-judgmental hyper-skilled MI clinician. Although highly caricatured these were nevertheless potent resources in the process of assimilation entailed by professionalization. Reproduced was the client who was inherently resilient and economic, and the clinician who was a skilled consultant in the art of self-care. Older discourses that constructed clients as diseased, unlearned or sad, and counsellors as agents of the state were marginalized. Often this was done by omission. Neo-liberal critiques of the older arrangement would cite how they are based on sickness and deficit, that the older models were totalizing, reductive, the relationship intrusive. No doubt there is some truth in this. In fact, much time and effort was invested in the sustenance of a sick role and if we take liberties with the English language and transpose the terms model and etiologies into the term discourse we can conclude that the clinicians created this sickness. However, people get sick. They lose control over alcohol and drugs and they become powerless. One could argue that Edgar Allen Poe, Dylan Thomas and Brendan Behan could have been saved from an untimely death by being simply motivated and reminded of simple goal setting. But that could only be argued form the high moral ground that neo-liberalism can provide. However, although reductionism to sickness, unlearning and emotionalism and indeed totalizing practices are railed against; in the neo-liberal arena there is a resounding hush about the reductionism to economy. This is a paradox to be addressed.

4.2. Neo-Liberalism

In order to analyze neo liberalism coherently, Larner (2000) recommends the Foucaultian approach of governmentality. She argues that this addresses the crucial elements of neo-liberalism namely paradox, subjectivity creation and the end of the state.

4.3. Paradox

Motivational Interviewing is liberatory in that it is strength based, resisting totalizing and labeling agendas, significantly opening spaces so that non-substance dependent people be given clinical attention. It resists a dependency between clinician and client. The concept of denial is diverted from a personality defect to a relationship difficulty often hinted at as being the inability of the clinician. This is a step forward. On the other hand these nondependent populations are now subject to (self) surveillance by experts in diagnosis. This is provided by the DSMIV, or published guidelines for normality (Alcoholic Advisory Council of New Zealand, 1997). Like the Twelve Steps, MI advances the importance of responsibility. However, unlike the responsibility concept of AA encapsulated in the slogan “We are responsible” (Alcoholics Anonymous, 1976), MI stresses individual responsibility. In addition, MI has raised the profile of addiction and substance abuse, which always is threatened by submersion into other professional fields.

4.4. Subjectivity

MI continues the practice of older etiologies of subjectivity creation, though this was not the term used in them. However, MI subjectivity creations are profoundly non deficit based. The client thus produced is a capable, responsible hyper-economic individual, who acts on their own self-care. Older subjectivities of illness, distress or powerlessness are relegated into silence. The person is imputed with a conduct for neo-liberalism.

4.5. End of the State

Strength based autonomous subjects freely acting on themselves as rational, balanced and prudential responsible individuals eschew the patrimony of state intervention. Entities such as disease, hurt, lack of education can be deleted from the vocabulary. There is a new freedom, facilitated by the newly embourgoised clinician, increasingly subsisting in new discourses that reside in networks of professionalization, evidence-base and fiscal concerns.

4.6. The Spirit of Motivational Interviewing

One idiosyncrasy of the AoD field has been the importance of what is termed spirituality or in older versions referred to as morality. To some extent with the rise of medical and behavioral discourses these were relegated. However in later versions of motivational interviewing the concept of spirituality is commandeered in a fashion conducive to a neo-liberal landscape. But this spirituality is different in important respects. Twelve Step therapy is located intimately in the collective and uses the word “we”, and the “I” is never mentioned. MI is very much based on the individual subject. Moreover the spirituality of MI is that of a neo-liberal orchestration advancing a morality conflated with economy and balance, in fact morality and economy are almost inseparable.

The spirituality of Twelve Steps and that of MI do have one further similarity, which comes from older wisdoms. The concept of governmentality refers to something more than just cognitively following a theory or etiology. It refers to very old wisdoms in making a project of the self, acting on oneself (Foucault, 1988) where action is more important than blind words or theories. This is akin to religious practices of old when one would act out certain regimens of living with only peripheral undue regard to theories. However this is a life of self-sacrifice, service abstinence, charity and poverty in the name of a higher power within a community such as AA with its often anti theoretical stance (Valverde, 1999). This is summed up in the prosaic phrase “walking the walk” (Alcoholics Anonymous, 1976).

With MI, however, and an alleged anti theoretical and non-etiological stance, the regimen is profoundly different. It is a life of individualism and active care of the self above all.

The spirit of Motivational Interviewing comprises collaboration, evocation andautonomy (Miller & Rollnick, 1991). It could be argued that these encapsulate the spirit of neo-liberalism, describing a business transaction between client and clinician conducted in the free marketplace.

4.7. Collaboration

This term nuanced with connotations of the market place describes two individuals in a professional relationship. The client is much like any consumer, rational, responsible but active in the way they collaborate. The clinician is also collaborative, skilled and non-judgmental with an ability to draw on expert knowledge, much like an accountant or lawyer. Significantly the term collaboration, is much more familiar to the market place where artifice, bargaining and negotiation are the rule. This contrasts with older albeit essentialist wisdoms. Neither the AA big book nor Bible nor Koran rates the word collaboration a mention nor indeed privilege the casuistry of the market place.

4.8. Evocation

The client is a rational, responsible individual, inherently active in their own self-care. As such they can be evoked into motivation by the hyper-skilled professional who can awake the unmotivated Lazarus from the dead. This skilled professional is above all a manager of people with a managerial ethos and morality. They, like any other manager in a neo-liberal environment, are committed to caring within economic constraints.

4.9. Autonomy

Again the client is a rational, responsible individualized self and the clinician’s role is to empower this so-called autonomy. Autonomy is a term often used by marginalized communities referring to a self sufficiency of the collective. However, this has been commandeered by MI being repositioned as an inherently individual descriptor. Autonomy in this neo liberal setting recognizes insight in clients when they perceive life as an economic individual project. They are interpellated into a neo-liberal life conduct and the embourgeuoised clinician implicated as a conduit.

Motivational Interviewing preaches balance, prudence and individuality, but not in any sense as a part of the nanny state. In fact preaching is the wrong word to use. It is virulently anti-preaching, so much so it protesteth too much. MI is not some part of an Orwellian (Orwell, 2008) nightmare. It augers in a brave new world (Huxley, 2007), progressive strength based yet undemocratic in the any real sense where the client is neither diseased nor unlearned, but free to choose. It produces a new ideal type. That some individuals chose chaos, defiance, disorder, and/or inebriation quite freely maybe defines what it is to be human.

5. Conclusion

Motivational Interviewing is a popular clinical practice in the substance abuse field that has proven efficacy but owes its popularity to political positioning as a brief intervention, conducive to producing clients imprecated into discourses of responsibility, individualism and economy. An analysis of MI technologies using the concept of governmentally illuminates how these technologies act as a conduit for subjectivity in a neo-liberal setting. The morality of this requires further interrogating if AoD workers are to maintain their ethical genesis. The fact that many of these clinicians retain access to older collective wisdoms creates a space where this is possible, and this would be a valuable area for further research. Post-structural analysis gives ready access to interrogate the constitutive effects of what they are required to enact in their in their newly embourgoised role. This is enlivened through their training when addressing their recovering and peer baggage, at times ethical itches, but also their ability to see without the professional and academic baggage that encumbers other established professionals. Lastly clinicians need to be asked if they are comfortable in their new accomplished as proxy members of neoliberal values albeit with an enlightened superficiality.

References

- Adrian, M. (2003). How Can Sociological Theory Help Our Understanding of Addictions? Substance Use & Abuse, 10, 1385- 1423.

- Alcoholic Advisory Council of New Zealand (1997). Upper Limits for Responsible Drinking. Wellington.

- Alcoholics Anonymous (1976). Alcoholics Anonymous (3rd ed.). New York: Alcoholics Anonymous.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Bell, A. (1997). Comparing Motivational Interviewing with Other Counselling Approaches Motivational Interviewing Training for Trainer’s Course Material. Auckland. (Based on Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991) Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behaviour.) New York: Guilford Press.

- Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in Capitalist America. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Burke, B., Arkowitz, H., & Menchola, M. (2003). The Efficacy of Motivational Interviewing: A Meta-Analysis of Controlled Clinical Trials, [Electronic Version]. Journal of Consulting and Clinical, 71, 843-861. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843

- Chaudron, C. W. (1988). Theories on Alcoholism. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation.

- Cohen, S. (2002). Folk Devils and Moral Panics (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Dean, M. (1999). Governmentality, Power and Rule in Modern Society. London: Sage Publications.

- Foucault, M. (1978). The History of Sexuality: Volume 1, an Introduction (R. Hurley trans.). Hammondsworth: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Giddens, A. (2002). Sociology. Cambridge: Cambridge Polity Press.

- Gilberd, D., & Gilberd, K. (2001). Basic Personal Counselling. Malaysia: Prentice Hall.

- Huxley, A. (2007). Brave New World. London: Vintage Books.

- Joseph, J., Breslin, C., & Skinner, H. (1999). Critical Perspectives on the Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change.

- Larner, W. (2000). Neo Liberalism: Policy, Ideology, and Governmentality [Electronic Version]. Studies in Political Economy, 63, 5-25.

- Manthey, T. J., Knowles, B., Asher, D., & Wahab, S. (2011). Strengths-Based Practice and Motivational Interviewing. Advances in Social Work, 12.

- May, C. (1997). Habitual Drunkards and the Invention of Alcoholism: Susceptibility and Culpability in Nineteenth Century England [Electronic Version]. Addiction Research, 5, 169-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/16066359709005258

- May, C. (2001). Pathology, Identity and the Social Construction of Alcohol Dependence [Electronic Version]. Sociology, 35, 385-401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/S0038038501000189

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change (2nd ed.). New York: Guildford Press.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd ed.). New York: Guildford Press.

- Orwell, G. (2008). Nineteen Eighty-Four. New York: Signet.

- Reinarman, C. (2005). Addiction as Accomplishment: The Discursive Construction of Disease [Electronic Version]. Addiction Research & Theory, 13, 307-320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/16066350500077728

- Rose, N. (1999). Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511488856

- Silverman, D. (2005). Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction. London: Sage Publications.

- Thombs, D. L. (1999). Introduction to Addictive Behaviours. New York: The Guildford Press.

- Todd, F. (2001). Co-Existing Substance Use and Mental Health Disorders. Christchurch, NZ: National Centre for Treatment Development.

- Valverde, M., & White-Mair, K. (1999). “One Day at a Time” and Other Slogans for Everyday Life: The Ethical Practices of Alcoholics Anonymous [Electronic Version]. Sociology, 33, 393-410.

- Zeeman, L., Poggenpoel, M., Myburgh, C. E., & Van der Linde, N. (2002). An Introduction to Educational Research: Discourse Analysis [Electronic Version]. Education, 123, 96-103.