Open Journal of Applied Sciences

Vol.06 No.08(2016), Article ID:70228,19 pages

10.4236/ojapps.2016.68056

Stabilizing the Lorenz Flows Using a Closed Loop Quotient Controller

James Braselton, Yan Wu

Department of Mathematical Sciences, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA, USA

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 13 June 2016; accepted 28 August 2016; published 31 August 2016

ABSTRACT

In this study, we introduce a closed loop quotient controller into the three-dimensional Lorenz system. We then compute the equilibrium points and analyze their local stability. We use several examples to illustrate how cross-sections of the basins of attraction for the equilibrium points look for various parameter values. We then provided numerical evidence that with the controller, the controlled Lorenz system cannot exhibit chaos if the equilibrium points are locally stable.

Keywords:

Lorenz Equations, Controller, Stability, Routh-Hurwitz Theorem, Chaos, Strange Attractor

1. Introduction

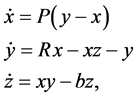

The Lorenz equations are given by

(1)

(1)

where ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are positive constants, called the Prandtl, Rayleigh, and Biot numbers, respectively.

are positive constants, called the Prandtl, Rayleigh, and Biot numbers, respectively.

The Lorenz equations first arose in the study of the fluid flow of the atmosphere by Lorenz [1] . The system has been studied extensively. Virtually all texts discussing nonlinear differential equations and dynamical systems discuss the Lorenz equations in some manner. Robinson [2] , Glendinning [3] , and Jordan and Smith [4] are just a few. Although initially the system was used to model the atmosphere, the equations have also been used in models of lasers [5] , thermosyphons [6] , motors [7] , electric circuits [8] , chemical reactions [9] and osmosis [10] .

In what follows, a physical interpretation of x, y, and z is important. We use Lorenz’s Lorenz derives system (1) in [1] from a simplified version of a partial differential equation formed by Saltzman [11] . For system (1), Lorenz states:

In these equations, x is proportional to the intensity of the convective motion, while y is proportional to the temperature difference between the ascending and descending currents, similar signs of x and y denoting that warm fluid is rising and cold fluid is descending. The variable z is proportional to the distortion of the vertical temperature profile from linearity, a positive value indicating that the strongest gradients occur near the boundaries.

The Prandtl number, P, is given by , where k is the coefficient of thermal diffusivity and

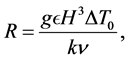

, where k is the coefficient of thermal diffusivity and  is the kinematic viscosity. The Rayleigh number determines whether heat is transferring primarily by conduction or convection and is given by

is the kinematic viscosity. The Rayleigh number determines whether heat is transferring primarily by conduction or convection and is given by

where g is the acceleration of gravity,  is the coefficient of volume expansion, H is the height of fluid, and

is the coefficient of volume expansion, H is the height of fluid, and  is a temperature contrast (refer to Saltzman [11] and Lorenz [1] for detailed explanations of the derivation of system (1) and meaning of the various parameters and variables). The Rayleigh number is the critical number governing the behavior of the Lorenz equations. Once R reaches a critical value, stable solutions of the system become unstable.

is a temperature contrast (refer to Saltzman [11] and Lorenz [1] for detailed explanations of the derivation of system (1) and meaning of the various parameters and variables). The Rayleigh number is the critical number governing the behavior of the Lorenz equations. Once R reaches a critical value, stable solutions of the system become unstable.

2. Review of Equilibrium Points of the Lorenz System and Local Stability Analysis

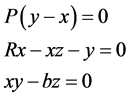

Solving

(2)

(2)

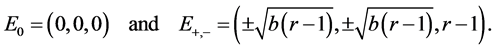

yields the rest points (equilibrium points)

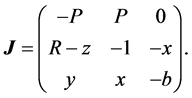

The Jacobian of system (1) is

(3)

(3)

Evaluated at , the Jacobian

, the Jacobian  has eigenvalues

has eigenvalues

For

In the case that

We now assume that

Evaluated at

The characteristic polynomials for both

The calculations begin to illustrate the complexities of this system. The Lorenz system is often used to illustrate how a very “simple” system can lead to chaotic behavior. Equation (5) shows a dramatic difference between global and local behavior. With simple examples we can show that the stability of

Because the coefficients of (5) are all nonnegative, the solutions of (5) will all have negative real part by the Routh-Hurwitz theorem if

For our calculations, we will follow a typical convention and set

2.1. Example: Stable

Before addressing the unstable situation and incorporating a controller to eliminate chaos in system (1) when

In Figure 1, we illustrate the basins of attraction for

Note the “speckled” regions in Figure 1, in these regions we see that system (1) is highly sensitive to initial conditions. For some initial conditions, the solutions converge to

The complexity of how the initial conditions affect the convergence of the solution to

2.2. Example: Stable

Interestingly, it is possible for

Figure 1. For

For the

In Figure 5 we illustrate the basins of attraction for

Figure 2. In three dimensions, depending upon the initial conditions, the solution quickly converges to either the gray region and then to

3. A Quotient Controller

The chaos/strange attractors observed in the Lorenz system in the context of a model of the atmosphere are interpreted to mean that over long (and, frequently, short) periods of time, the weather is not predictable. Hence, controlling the solutions to the Lorenz system to eliminate chaos/strange attractors are interpreted there is a means by which to make weather forecasts more accurate over longer (and shorter) periods of time. Shen [14] , generalizes the Lorenz equations with two additional modes and analyzes a 5-dimensional Lorenz system. Shen’s 5-dimensional system exhibits strange attractors for larger R values than the original 3-dimensional Lorenz system. In other words, for some R values for which system (1) exhibits chaos, the corresponding 5-dimensional system analyzed by Shen does not. As with Shen, our goal is to eliminate chaos by reducing the value of R via a quotient controller as a perturbation of R. We do this by incorporating a quotient controller into y-equation of system (1).

We now incorporate a quotient controller of the form

into the y-equation in the Lorenz system. We use a quotient controller in the y-equation to control R rather than a linear control in the x-equations as done by Braselton and Wu [15] , because the y and z states are (theoretically) easily measurable (compared to x), while R is proportional to the external heat applied to the system. Therefore, the controller serves as an actuator to perturb the heat source. The quotient controller is applied to perturb the Rayleigh number, R, which is the key parameter to initiating chaos in the Lorenz system, as follows

Figure 3. Projections of Figure 2 into the x-y, y-z, and x-z-planes.

where

Figure 4. Plots of x, y, and z as functions of t.

3.1. Local Stability Analysis

Solving

results in the equilibrium points

Figure 5. For

The Jacobian for (8) is

Figure 6. In the speckled regions in Figure 5, solutions converge to the strange attractor on the left. On the other hand, in the gray regions, solutions converge to

after dividing by

If

then by the Routh-Hurwitz theorem, the real part of the roots of the characteristic polynomial of (11) evaluated at the equilibrium points (10) will all have negative real part and, consequently,

The roots of

・

-

-

or

・

If these conditions are not satisfied, then the real part of the roots of the characteristic polynomial of (11) evaluated at the equilibrium points (10) will have a positive real part and, consequently,

because of the term

the system.

The values

Figure 7 shows a portion of the region where

the shaded region, the equilibrium points (10) will be locally stable. Also, if k is sufficiently large,

3.2. Example:

Using

To stabilize the system, we first solve

Figure 7. For

Figure 8. Without a control, when

evaluated at

Numerically, we see that there is a ball centered at each of

The complexity of the basins of attractions are even more apparent when zooming in near one of the equilibria or zooming out as shown in Figure 11.

These figures provide numerical evidence that controlled system has no limit cycles. For those initial

Figure 9. For k-values on the gray line in the shaded region,

conditions in the black region, the solutions converges to

The initial conditions have a major affect on the convergence of a solution to

To investigate the existence of a strange attractor as observed in Section 2.2, for each

3.3. Example:

Using

Figure 10. For

and for R-values in this range (

Figure 11. On the left, zooming in near

Figure 12. In three dimensions, depending upon the initial conditions the solution quickly converges to either the gray region and then to

Figure 15 illustrates the basin of attraction for various values of

Figure 13. Projections of Figure 12 into the x-y, y-z, and x-z-planes.

To investigate the stability of

3.4. Example:

To investigate how implementing our controller affects the stability of solutions of the Lorenz equation, we have examined an extreme range of R and k-values hoping that these simulations indicate the the global behavior that we have numerically observed.

Figure 14. Plots of x, y, and z as functions of t.

Our last example involves a large R-value and a small k-value. We repeat the example in Section 3.4 except we use

The situation appears to be similar to the situation discussed previously with small k-values. In Figure 16, observe the “speckled” region as before where solutions may converge to

As we did with the previous examples, to investigate the existence of a strange attractor as observed in Section 2.2, for each

Figure 15. If k is large, it appears as though the boundary between the basins of attraction for

solutions converge to

Note that we were able to produce “almost strange attractors” in the sense that the trajectories appeared to be chaotic at first-but eventually converged to either

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we revisited the three-dimensional Lorenz system. We illustrated how the Lorenz system can exhibit chaos (or, strange attractors) even when the non-trivial equilibrium points are locally stable.

We then introduced a closed loop quotient controller into the three-dimensional Lorenz system, computed the equilibrium points and analyzed their local stability. We use several examples to illustrate how cross-sections of the basins of attraction look for various parameter values. We then provided numerical evidence that with the

Figure 16. For

controller, the controlled Lorenz system cannot exhibit chaos if the equilibrium points are locally stable.

Our controller controlled the heat source, R. Of course, in the context of Earth’s atmosphere, the design and construction of a controller that could truly control Earth’s R-value would be an engineering miracle.

About the Computations

All computations were carried out using Mathematica Version 10 [12] . Readers can obtain the Mathematica notebooks used for the computations and graphics here by sending an email request to jbraselton@georgiasouthern.edu.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Editor and the referees for their comments.

Cite this paper

James Braselton,Yan Wu, (2016) Stabilizing the Lorenz Flows Using a Closed Loop Quotient Controller. Open Journal of Applied Sciences,06,560-578. doi: 10.4236/ojapps.2016.68056

References

- 1. Lorenz, E.N. (1963) Deterministic Non-Periodic Flows. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 20, 130-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1963)020<0130:DNF>2.0.CO;2

- 2. Robinson, C. (1999) Dynamical Systems: Stability, Symbolic Dynamics, and Chaos. 2nd Edition, CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, Florida.

- 3. Glendinning, P. (1994) Stability, Instability, and Chaos: An Introduction to the Theory of Nonlinear Differential Equations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511626296

- 4. Jordan, D.W. and Smith, P. (2007) Nonlinear Ordinary Differential Equations: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers. 4th Edition, Oxford University Press, New York.

- 5. Haken, H. (1975) Analogy between Higher Instabilities in Fluids and Lasers. Physics Letters A, 53, 77-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0375-9601(75)90353-9

- 6. Tanner, J.S. (2007) State Feedback Control of a Single-Loop Thermosyphon System via a Quotient Controller. Master’s Thesis, Georgia Southern University.

- 7. Hermati, N. (1994) Strange Attractors in Brushless DC Motors. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Fundamental Theory and Applications, 41, 40-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/81.260218

- 8. Cuomo, K.M. and Oppenheim, A.V. (1993) Circuit Implementation of Synchronized Chaos with Applications to Communications. Physical Review Letters, 71, 65-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.65

- 9. Poland, D. (1993) Cooperative Catalysis and Chemical Chaos: A Chemical Model for the Lorenz Equations. Physica D, 65, 86-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-2789(93)90006-M

- 10. Tzenov, S. (1994) Strange Attractors Characterizing the Osmotic Instability. arXiv:1406.0979.

- 11. Saltzman, B. (1962) Finite Amplitude Free Convection as an Initial Value Problem-I. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 19, 329-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1962)019<0329:FAFCAA>2.0.CO;2

- 12. Wolfram Research (2016) Mathematica 10.0. Champaign, Illinois.

- 13. Sprott, J.C. (2013) Tri-Stability in the Lorenz System. Technical Report, Department of Physics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin. http://sprott.physics.wisc.edu/technote/tristab.htm

- 14. Shen, B.-W. (2014) Nonlinear Feedback in a Five-Dimensional Lorenz Model. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 71, 1701-1723. http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-13-0223.1

- 15. Braselton, J. and Wu, Y. (2016) Applying Linear Controls to Chaotic Continuous Dynamical Systems. Open Journal of Applied Sciences, 6, 141-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojapps.2016.63015