Surgical Science

Vol. 3 No. 3 (2012) , Article ID: 18042 , 4 pages DOI:10.4236/ss.2012.33028

Chilaiditi Syndrome: The Pitfalls of Diagnosis

1General Surgery Department, Chang-Bing Show Chwan Memorial Hospital, Changhua, Chinese Taipei

2IRCAD Taiwan, Chang-Bing Show Chwan Memorial Hospital, Changhua, Chinese Taipei

3Division of General Surgery, Department of Surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital, Taipei, Chinese Taipei

4Department of Medicine, Chang-Bing Show Chwan Memorial Hospital, Changhua, Chinese Taipei

Email: *linjh93@yahoo.com.tw

Received May 28, 2011; revised December 19, 2011; accepted February 14, 2012

Keywords: Chilaiditi Syndrome; Hepatodiaphragmatic Interposition; Chilaiditi

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Chilaiditi’s syndrome is the hepatodiaphragmatic interposition of the colon. Its diagnosis poses challenge to clinicians, and misdiagnosis may results in unnecessary exploratory laparotomy being performed. The purpose of this study was to report our experience in diagnosis, management, and clinical outcome of patients with Chilaiditi’s syndrome. Methods: Nine cases of Chilaiditi’s syndrome from April 2005 to January 2007 at one institute. The clinical characteristic, imaging studies, management and results were recorded. Results: Six patients presented with abdominal distension (2 patients with abdominal pain; 5 patients with constipation), while Chilaiditi’s syndrome in the other three patients were found incidentally. All patients underwent chest X-ray. The Chilaiditi’s sign could be detected in seven patients; while the other two patients presented with no specific finding. Abdominal plain films (KUB) were all reviewed. Most of the patients (n = 8) showed ileus and one patient showed no specific finding. Impacted stool could be detected in five of nine patients. Abdominal ultrasound was performed in two patients. Gallstones were detected in one of them while the other revealed no specific finding. Six of nine patients underwent CT of abdomen, one of them revealed bowel loops in bilateral subphrenic space. One patient underwent subtotal colectomy because of volvulus of sigmoid colon. Five patients were treated with laxative and enema successfully and had been remained asymptomaticcally for a mean follow-up of 6.6 months. The other three cases were under observation. Conclusions: Presence of haustral folds of bowel loops may help us in diagnosing Chilaiditi’s syndrome. The left lateral decubitus abdominal plain film can also help to differentiate between pneumoperitoneum to Chilaiditi’s sign. Most of the cases with Chilaiditi’s syndrome can be resolved with conservative treatment and surgical intervention was reserved for patients with sign of systemic toxicity or peritonitis.

1. Introduction

Chilaiditi’s sign is the anatomical description of interposition of the colon between the liver and the diaphragm. It was first described by Demetrius Chilaiditi in 1910 [1,2]. Most commonly, it’s an a symptomatic radiologic finding [3]. However, it is sometimes associated with symptoms ranging from mild abdominal pain to acute intermittent bowel obstruction [3]. The differential diagnosis of Chilaiditi’s syndrome includes pneumoperitoneum, pneumobilia, and hepatic-portal-venous gas (HPVG). Herein, we present nine patients of Chilaiditi’s syndrome and one of them was misdiagnosed. The therapy for Chilaiditi’s syndrome is conservative nasogastric decompression and bed rest. Rarely is surgical intervenetion indicated [3]. However, misdiagnosis made by clinicians may result in unnecessary surgery. Herein, these cases were further analyzed and remind clinicians of the clinical findings of Chilaiditi’s syndrome to decrease unnecessary surgeries.

2. Patients and Method

From April 2005 to January 2007, totally nine adult patients with radiological findings of Chilaiditi’s sign were enrolled in this study. There were 8 men and 1 woman, mean age, 69 years, range from 60 - 83 years. The diagnosis was made by the presence of the colon or bowel gas in the space between liver and diaphragm. The clinical characteristics (age, gender, clinical presentation, underlying diseases) and radiological findings (chest X-ray, abdominal X-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography) were reviewed.

All patients received chest and abdominal X-ray examination. Only two of them underwent ultrasound, one was because of medical history of gallstones and another presented with abdominal distension. The ultrasound was rarely to check and confirm Chilaiditi’s syndrome, because most of these patients presented with abdominal distension and could not be easily examined by ultrasound. CT was performed in six patients, the indications for CT were abdominal distention in three patients, air in subphrenic space for further study in two patients, and gallstones for further study in one patient. The operative findings, management and outcome were also recorded.

3. Results

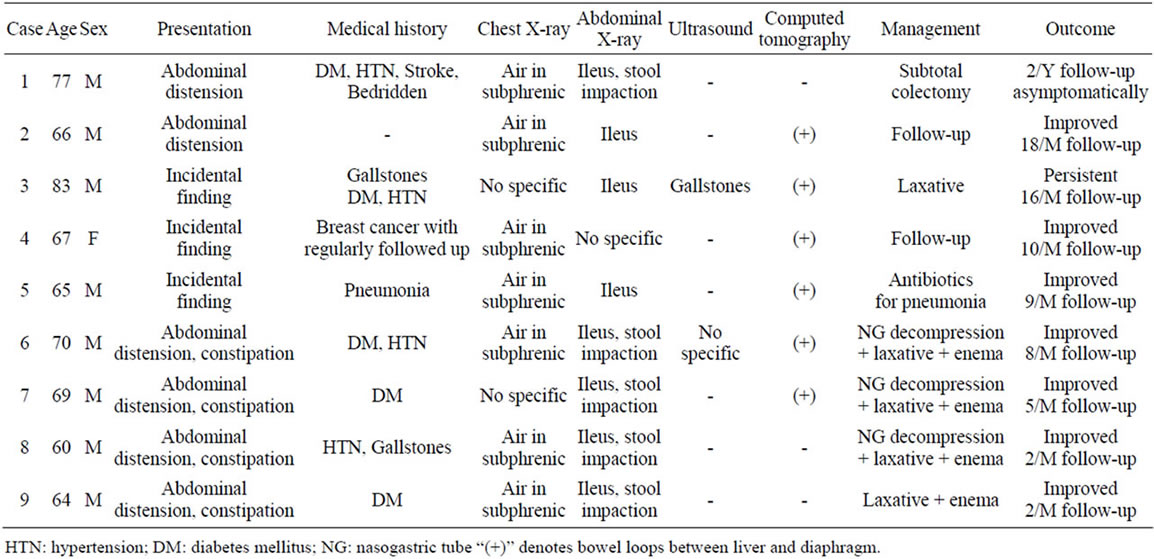

The demographics of these patients were shown in Table 1.

The average age was 69 years. Six patients presented with abdominal distension (2 patients with abdominal pain; 5 patients with constipation), while Chilaiditi’s syndrome in the other three patients were found incidenttally. Five patients had the history of diabetes mellitus (DM). Four patients had hypertension, one patient had breast cancer, one patient had gallstones, and one patient suffered a previous stroke and was bedridden.

All patients underwent chest X-ray. Chilaiditi’s sign could be detected in seven patients; while the other two patients presented with no specific finding.

Abdominal plain films (KUB) were reviewed. Most of the patients (n = 8) showed ileus and one patient showed no specific finding. Impacted stool could be detected in five of nine patients. Abdominal ultrasound was performed in two patients. Gallstones were detected in one while the other showed no specific finding.

Six of nine patients underwent CT of the abdomen, one of them revealed bowel loops in bilateral subphrenic space.

One patient (No. 1) presented with Chilaiditi’s syndrome caused by volvulus of sigmoid colon and underwent subtotal colectomy. He remained well during the two-year follow-up.

Five of nine patients (Nos. 3, 6-9) underwent conservative treatment included NG decompression, laxative and enema. Most of these patients presented with abdominal distention and constipation. After treatment, they remained asymptomatic for a mean follow-up of 6.6 months.

The other three patients (Nos. 2, 4, 5) with Chilaiditi’s sign were discovered incidentally. Their symptoms and findings of radiology were improved after regular follow-up.

4. Discussion

Hepatodiaphragmatic interposition of the colon was known as Chilaiditi’s sign. The incidence is about 0.1% - 0.25% [2]. When it is accompanied with clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and constipation, it is known as Chilaiditi’s syndrome [3]. Several causes including absence of suspensory ligaments of transverse colon, atrophic or small liver, segmental agenesis of the right lobe of the liver, abnormality of the falciform redundant mesocolon, redundant or dilated colon, and volvulus of colon have been reported to be associated with Chilaiditi’s syndrome [4-6]. In addition, mental deficiency may also be associated with Chilaidi’s syndrome [2].

The etiology is not very clear; but may be associated

Table 1. Summary of clinical characteristics, imaging findings, treatments and outcomes in 9 patients with Chilaiditi’s sign.

with paritial intestinal obstruction. Most of our patients were presented with abdominal distension and constipation; the X-ray finding showed ileus and impaction of stool. So, we thinck Chilaiditi syndrome may be due to the obstruction of bowel.

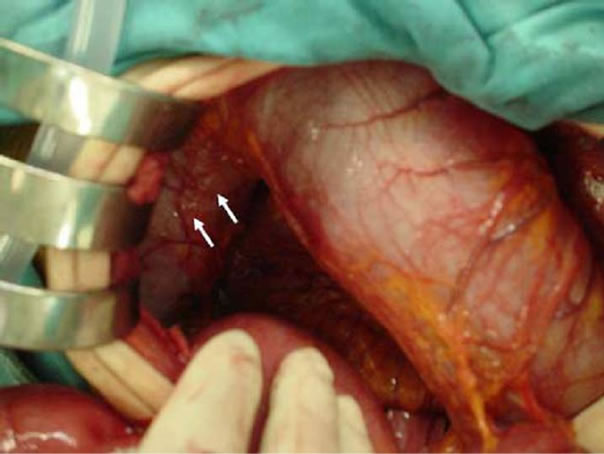

Chilaiditi’s sign is often an incidental finding and asymptomatic. However, most of the cases (6 in 9) in our study had complaints about the abdomen. Therefore, taking the medical history and careful physiccal examination are important for surgeons. Most of the patients (5 in 9) had history of constipation. As shown in Figure 1, constipation or impacted stool would make the transverse colon dilate, causing the proximal transverse colon (white arrow) to float over the liver in case of abnormality of the falciform redundant mesocolon or redundant transverse colon.

However, old patients or patients with dementia can hardly state their complaints, and it is also difficult to obtain their medical history or perform through physical examination.

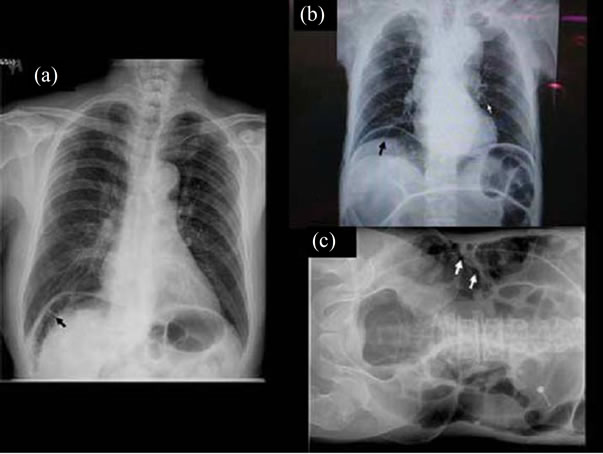

Radiological studies may be helpful in this situation. Most of the patients with Chilaiditi’s sign can be easily diagnosed via chest X-ray. Figure 2(a) shows the haustral folds of bowel loops (arrow). However, the haustral folds of bowel loops may not be seen in chest X-ray (Figure 2(b), arrow). Under this condition, the left lateral decubitus abdominal plain film may help to differentiate between pneumoperitoneum and Chilaiditi’s sign (Figure 2(c), white arrow). Neither Figure 2(b) nor 2(c) shows the haustral folds of bowel loops but they can be seen in the left decubitus abdominal plain film.

Although Sato et al. reported that ultrasound is helpful in diagnosing Chilaiditi’s syndrome [7], it is rarely performed in our study. The reasons are that most of the cases can be diagnosed by X-ray and CT of abdomen provides more information. However, ultrasound may be

Figure 1. The transverse colon is dilated and redundant, resulting in proximal transverse colon “floating” over the liver.

Figure 2. Chest X-ray shows haustral folds with markings in the right subphrenic region (a). Interposition of bowel loop between the liver diaphragm mistaken initially for free air under diaphragm (b). The left lateral decubitus abdominal plain film shows haustral folds with markings; not free air (c).

helpful in distinguishing between Chilaiditi’s syndrome and pneumoperitoneum.

The management of Chilaiditi’s syndrome varies because of the different etiologies of Chilaiditi’s syndrome. They include both operative and nonoperative approachs. Saber et al. reported that 26% of patients needed operative management [4], while the majority required nonoperative treatment, including bowel decompression and repeated radiography. Bowel decompression may be both diagnostic and therapeutic [4]. Surgical intervention is necessary in case of bowel ischemia or obstruction from intestinal volvulus [4]. In our cases, only one patient (11%) needed operative treatment because of volvulus of sigmoid colon, while most of our patients needed nonoperative management and observation.

As seen in Figure 1, the transverse colon was redundant and dilated because of constipation or distal obstruction, and the proximal part floated over the liver. We can try nasogastric decompression, laxatives or enemas to relieve symptoms. Most of the patients could be easily treated. If the symptoms were persistent, surgical intervention may be indicated. We consider nasogastric decompression, repeated laxatives and enemas helpful for patients with Chilaiditi’s syndrome, especially for patients whose abdominal plain film showed impacted stool. However, exploratory laparotomy may be indicated in patients with peritonitis or signs of toxicity. For the resistant cases, the surgical intervention maybe indicated.

In conclusion, Chilaiditi’s syndrome is not common but important, and it can be easily mistaken as pneumoperitoneum. Most of the patients with Chilaiditi’s sign are found incidentally. However, patients usually have both Chilaiditi’s sign and complaints of abdomen when referred to clinicians. To diagnose Chilaiditi’s syndrome is still a challenge for clinician. First, try to look for the presence of haustral folds of bowel loops. Once the absence of haustral folds is confirmed, further examining the left lateral decubitus abdominal plain film to help differentiate between pneumoperitoneum and Chilaiditi’s sign. Ultrasound may be helpful in making distinction. Abdominal CT can differentiate between free air and Chilaiditi’s sign once the X-ray showed equivocality. Most of the cases with Chilaiditi’s syndrome can be resolved with nasogastric decompression, repeated laxatives and enemas. Surgical intervention is reserved for patients with sign of systemic toxicity or peritonitis. This report reminds clinicians of the clinical findings of Chilaiditi’s syndrome to decrease unnecessary exploratory laparotomies.

REFERENCES

- D. Chilaiditi, “Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose im Allgemeinen im Anschlussan Drei Falle von Temporarer, Partieller Lebererlagerung,” Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Nuklearmed Erganzungsband, Vol. 16, 1910, pp. 173-208.

- C. N. Lekkas and W. Lentino, “Symptom-Producing Interposition of the Colon: Clinical Syndrome in Mentally Deficient Adults,” JAMA, Vol. 240, No. 8, 1978, pp. 747-750. doi:10.1001/jama.1978.03290080037020

- G. R. Orangio, V. W. Fazio, E. Winkelman, et al., “The Chilaiditi Syndrome and Associated Volvulus of the Transverse Colon: An Indication for Surgical Therapy,” Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, Vol. 29, No. 10, 1986, pp. 653-656. doi:10.1007/BF02560330

- A. A. Saber and M. J. Boros, “Chilaiditi’s Syndrome: What Should Every Surgeon Know?” American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 71, No. 3, 2005, pp. 261-263.

- J. J. Plorde and E. J. Raker, “Transverse Colon Volvulus and Associated Chilaiditi’s Syndrome: Case Report and Literature Review,” American Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol. 91, 1996, pp. 2613-2616.

- Y. Kurt, S. Demirbas, G. Bilgin, et al., “Colonic Volvulus Associated with Chilaiditi Syndrome: Report of a Case,” Surgery Today, Vol. 34, No. 7, 2004, pp. 613-615. doi:10.1007/s00595-004-2751-3

- M. Sato, H. Ishida, K. Konno, et al., “Chilaiditi Syndrome: Sonographic Findings,” Abdominal Imaging, Vol. 25, No. 4, 2000, pp. 397-399.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.