Advances in Microbiology

Vol.4 No.9(2014), Article ID:48192,11 pages

DOI:10.4236/aim.2014.49061

Use of LPS Extracts to Validate Phage Oligopeptide That Binds All Salmonella enterica Serovars

I-Hsuan Chen1, Kiril Vaglenov1, Yating Chai2, Bryan A. Chin2, James M. Barbaree1*

1Department of Biological Sciences, Auburn University, Auburn, USA

2Materials Engineering Program, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Auburn University, Auburn, USA

Email: *barbajm@auburn.edu

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

![]()

![]()

Received 14 May 2014; revised 16 June 2014; accepted 12 July 2014

ABSTRACT

Phage Display technology provides a mechanism for us to make bio-recognition elements on biosensors for detection of Salmonella enterica serovars. In the procedure, the filamentous M13 bacteriophage is used for acquiring peptides that have a high affinity for the target recognition. Our approach in this study was to develop peptide structures in the pIII region of this thread-shaped virus. A phage pIII library was used to perform biopanning for the phage clones to bind the target Salmonella serovars. The clones were bound, washed, eluted and amplified four times. Then, the phage peptides were sequenced tested for specificity using ELISA procedures. In this project to make a biosensor for all relevant Salmonella enterica serovars, we used common LPS salmonellae antigens as targets in the biopanning procedure. This enabled us to have a phage probe specific for all serovars of Salmonella enterica excluding the typhoid organisms. The final phage was then immobilized onto an electromagnetic platform to complete the biosensor, which gives us the realtime ability to measure resonance changes that indicate mass loading. The mass loading is an indication of binding to the target cells. Our current data with an ELISA procedure show the phage probe’s high affinity for salmonellae, very low cross-reactivity with Escherichia coli, Shigella, and no cross-reactivity to Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes. The biosensor with the phage showed that the capture ability for Salmonella serovars is thirty times higher than the control sensor. This biosensor is a candidate for detection of Salmonella in food and other settings.

Keywords: LPS Extractions, Phage Display, Salmonella, Biosensors

1. Introduction

Salmonella enterica is commonly associated with food poisoning in countries all over the world. This species has approximately 2500 serovars [1] that are divided into four different O-antigen groups. A rapid test for detecting all relevant ones is desirable to improve food safety procedures. Phage-based magnetoelastic (ME) biosensors have been recently developed as a novel and real-time method for Salmonella typhimurum detection in foods [2] -[5] . The performance of this ME biosensor relies on the adhesion characteristics of the phage coating on the sensor surface through Au deposition and also the phage binding affinity to bacterial targets [4] [6] . The goal of this study was to develop a specific oligopeptide phage probe as a bio-recognition element on ME biosensor platforms for detecting all Salmonella enterica serovars in O-antigen groups B, C, and D that cause food borne illness.

In order to produce highly specific phage probes, use of simple and common Salmonella cell surface targets, like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antigens, is a logical approach. LPS is the major component of outer membrane protein in Gram-negative bacteria, including all Salmonellae. The structure of LPS consists of a polysaccharide chain (O-antigen repeats and a core oligosaccharide) and lipid A; the latter is responsible for the partial toxicity of the bacteria. Here, we modified a phenol-chloroform-petroleum ether (PCP) extraction method [7] [8] to purify the extraction of LPS from the cell surface of nineteen representative foodborne Salmonella enterica serovars in O-antigen B, C, and D groups. Group A was not included since it contains the typhoid serotypes.

We used the above purification techniques in concert with Phage Display to improve upon the traditional combinatorial oligopeptide chemistry of testing random peptides on the coat proteins pIII of a bacteriophage [9] [10] . The major advantages of expressing oligopeptides as phage coat proteins include enhanced stability of the oligopeptides, ease of handling, and simplified purification of the oligopeptides. To isolate desired phages with oligopeptides that interact with the ligand of interest, an affinity selection designated as “biopanning” was conducted. The affinity-selected phages can first be validated by immuno-based methods, like ELISA [9] -[12] . Here, we demonstrated two types of ELISA methods that tested the selected phage-borne peptides against O-antigen LPS directly, and through Salmonella’s whole cells in ELISA. The final phage, which showed the highest specificity and selectivity through both assays, was on a ME biosensor and checked for binding to Salmonella.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria Strains and Preparations

All nineteen Salmonella enterica serovars used in this study are listed in Table1 Other bacteria in this study were Shigella sonnei (ATCC25931), Shigella flexneri (ATCC12022), and E. coli O157:H7, and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213) and Listeria monocytogenes (ATCC 7644). The steps of preparing nineteen Salmonella enterica serovars for LPS extraction will be described separately in 2.2. Bacterial preparations for whole cell ELISA are described here. Each bacteria strain was grown in Lennox Broth (LB broth) overnight in a shaking incubator at 37˚C. Overnight bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 5500 rpm in for 10 min at 4˚C and re-suspended in PBS twice. Bacteria concentrations were then adjusted as required in PBS by spectrum measurements (OD 1.0 at 600 nm ≈ 5 × 108 cfu/ml).

2.2. LPS Extraction by Modified Phenol-Chloroform-Petroleum Ether (PCP) Method

A PCP extraction method was modified to maximize the extraction of LPS from nineteen representative foodborne Salmonella enterica serovars in O-antigen B, C, and D groups [7] [8] . All nineteen Salmonella enterica serovars in three O-antigen groups were listed in Table2

A shaker incubator set at 200 rpm was used to incubate overnight 10 ml aliquots of LB broth inoculated with cultures of Salmonella enteritica serovars. Each culture was then centrifuged twice at 5500 rpm in for 10 min at 4˚C. After each centrifugation, the resulting pellets were re-suspended in 10 ml and 4 ml PBS, respectively. The bacterial solution was then sonicated at 20 second intervals for 4 times on ice, and followed by centrifugation at 5500 rpm for 10 min at 4˚C. Equal amount of phenol-chloroform (1:1, vol/vol) were added and mixed vigorously with the supernatant. After centrifugation at 8500 × g for 10 min at 4˚C, the LPS containing fluid in the upper layer was captured without contamination from the white precipitation, which contained protein contaminates.

Sodium acetate was added to make a final concentration of 0.5 M with the addition of 2 volumes of 95%

Table 1 . List of nineteen foodborne Salmonella enterica serovars in O-antigen B, C, and D groups used in this research.

Table 2. Summary of phage peptide sequences identified by biopanning against Salmonella LPS.

.

.

ethanol in a 15 ml conical tube. After thorough mixing, the tubes were stored at −20˚C overnight, and then centrifuged twice at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4˚C. The resulting pellet from the first centrifugation was carefully washed with 1 ml of 70% ethanol. After the second centrifugation, the pellet was then air dried and weighed. The LPS pellet was later dissolved by adding 100 ul 1 M Tri-HCl (pH 8.0) and treated with Proteinase K (100 ug/ml) at 65˚C for 1 hr. The final LPS samples were stored at −20˚C.

The extracted LPS suspensions were confirmed by gel electrophoresis (4% - 12% SDS-PAGE) followed by a silver stain [7] . LPS content from each O-antigen group was calibrated and adjusted to 100 ug/ml through the LAL endotoxin test (Pierce LAL Chromogenic Endotoxin Quantitation Kit, Rockford, IL) for later use.

2.3. Phage Display Method

A Ph.D. 12 Phage Display Library from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA) was used for biopannings. In order to enhance the isolation of probes with higher specificity, we first panned the library with plastic and BSA (5 mg/ml) on 35 mm Petri Dishes. Four rounds of biopanning, which used the LPS (100 ug/ml) from each O-antigem group as targets, were performed to isolate LPS specific phages. Biopanning procedures were those described in New England Biolab’s Ph.D. 12 Phage Display Library manual.

2.4. Phage Characterizations and ELISA Screening

Randomized phage clones were selected from LPS O-antigen B, C, and D groups’ biopannings, and then characterized using phage PCR and sequencing. Selected phages with confirmed sequences were amplified and titered.

The LPS ELISA procedure was used to first screen phages with LPS binding affinity and specificity. LPS of 100 ug/ml was immobilized on a 96 well ELISA plate. BSA (5 mg/ml) was used for blocking the non-LPS binding surfaces on plate. Phages (1011 virons/ml) binding to LPS were then detected with rabbit anti-M13 IgG antibody (Abcame#ab6188, Cambridge, MA) and anti-rabbit conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Sigma #A3687, St. Louis, MO) by achromogenic substratepara-Nitrophenylphosphate (Sigma#N9389, St. Louis, MO). Each ELISA reaction layer was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with gently shaking and then washed three times with TBS/0.05% Tween. ELISA signals representing the relative activity of AP were read with a BioRad microtiter plate reader (Hercules, CA) in the kinetic mode for one hour at an optical density of 415 nm. M13KE control phage (vector phage without peptide insertion—New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) was used as the control phage in all ELISA tests. Phages with constantly high affinity to all three LPS O-antigens were chosen as candidate phages.

A whole cell ELISA procedure (WC ELISA) was also used later to confirm the binding specificity of candidate phages to bacterial cell mixtures of Salmonella and other related Enterobacteriaceae members such as Shigella sonnei, Shigella flexneri, and E. coli O157:H7, plus two Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes. Procedures for the WC ELISA were the same as described in LPS ELISA, except the target layer was immobilized bacterial cells (5 × 108 cfu/ml). Bacterial preparations were described at 2.1.

2.5. Biosensor Study

Magnetoelastic (ME) biosensors were made and obtained from Dr. Bryan A. Chin’s lab in the Materials Engineering Program, Auburn University, AL. Each ME sensor was materially fabricated from METGLAS_2826 MB alloy ribbon (Honeywell Inc., Melville, NY, USA) and diced into a strip shape with the size of 4 mm × 0.8 mm × 0.028 mm. Before depositions of Cr and Au (gold) layer, the ME resonator platforms were ultrasonically cleaned in acetone and ethanol, and then annealed at 220˚C for 2 h in a vacuum (10−3 Torr) to remove any remaining residual [5] . The phages bound to the gold coated layer due to hydrophobic binding, weak hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and covalent binding between the gold surface and cysteine residues in the minor coat protein of phage [12] [13] .

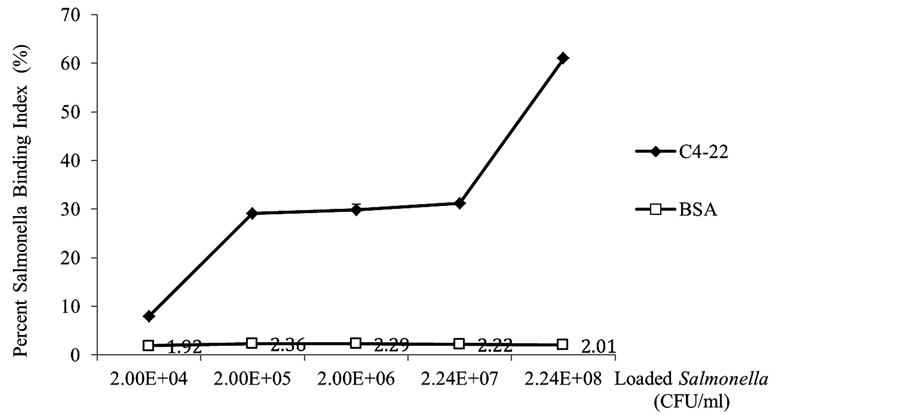

Each ME biosensor was coated with phage C4-22 (1010 virons in 100 µl) for an hour at room temperature and then washed three times with TBS/0.05% Tween. BSA (5 mg/ml) was used for blocking the non-phage binding surfaces on sensors before washing with TBS/0.05% Tween three times. Sensors coated only with BSA served as controls. Phage sensors and BSA sensors were used to capture Salmonella typhimurium solutions of different concentrations (5 × 104 to 5 × 108 cfu/ml) for an hour at room temperature. Cells of Salmonella typhimurium detected on the sensor were washed with TBS/0.5% Tween three times and eluted with 0.2 M Glycine (pH 2.2) to break phage-Salmonella binding. The eluted Salmonella solution was then neutralized with 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.1) and transferred onto TSA plates for bacterial counts using a standard aerobic plate count method (APC).

. Ac is the average Salmonella cell counts (triplicates)

eluted from one Sensor. Ci is the input Salmonella concentration on the sensors.

Each Salmonella concentration (loading concentration) had three sensors experiments

to calculate the means ± standard deviations among each test group.

. Ac is the average Salmonella cell counts (triplicates)

eluted from one Sensor. Ci is the input Salmonella concentration on the sensors.

Each Salmonella concentration (loading concentration) had three sensors experiments

to calculate the means ± standard deviations among each test group.

3. Results and Discussion

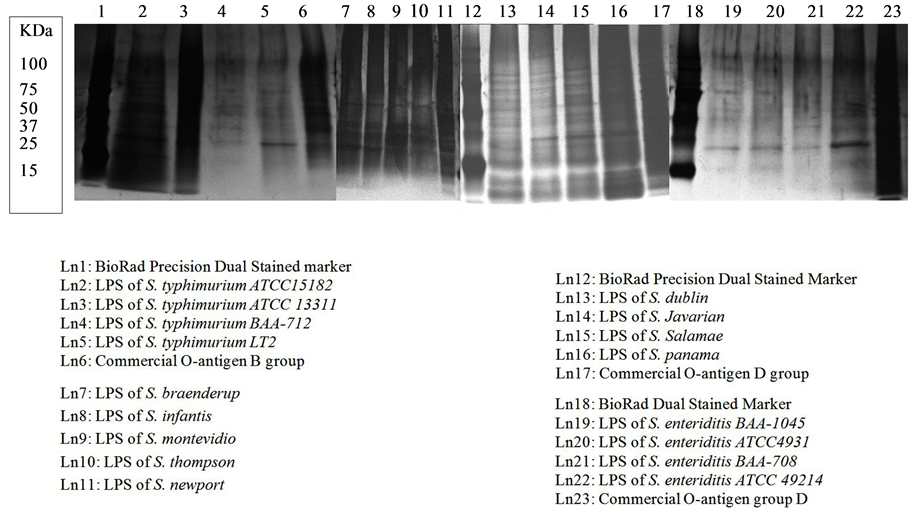

3.1. SDS-PAGE Analysis and Silver Staining of LPS

There are two main methods for LPS extractions: hot phenol procedure by Westphal et al., 1965 [14] and PCP method by Kido et al., 1990 [8] . The phenol-based method has been widely used for the LPS because of its high yield [15] [16] . PCP method is well known for its ability to reach high purity level of LPS, but it is usually laborious and sometimes leads to a low yield [8] [17] . However, difficulties were encountered in the use of above methods when extracting all nineteen LPS fragments from nineteen S. enterica serovars in the three O-antigen groups (data not shown). In this part of study, efforts were made to combine and modify the above methods to have a standard way of extracting all LPS needed.

With the adjusted step in the PCP method coupled with sonication to break bacteria cells (described in Materials and Methods), LPS from all nineteen Salmonella enterica serovars were successfully extracted. The silver stained SDS-PAGE gel analysis was used to detect and visualize the purified LPS. In Figure 1, all nineteen LPS expressed a typical ladder-like pattern of bands within a Dual Protein Marker molecular weight range of 100 to 15 KDa. This is consistent with findings in numerous studies [18] -[20] . The LPS profile of Salmonella is normally shown in molecular weight between 94 - 14.4 KDa [7] [21] . It was also noticed that four LPS concentrations (intensity of bands) of Salmonella enterica enteriditis showed relatively lighter colors in compared to other Salmonellae (Figure 1). This indicated a lower yield of LPS with the S. enteritidis serovars. We observed that the LPS content from different isolates, strains, and species can vary even under the same conditions of culturing volume and time, and the use of the same procedure.

There are advantages of using the modified PCP method in this study. First, the LPS-chloroform-phenol layer prevents the direct touching of the contaminated protein during transferring the LPS in the upper layer. Chloroform gave enough distance beneath the phenol layer for easiness of transferring LPS layer into other tubes. Second, instead of using cell lysis buffer or heat to break the cells, sonication was used directly to burst the bacteria cells and release more LPS from the cells. This resulted in a higher yield of LPS in one preparation. These steps may be the key to successful extraction of all LPS in nineteen Salmonella enterica serovars. The more definitive use of LPS extracts from target cells promises to be important to the biopanning process.

3.2. Biopanning and Phage Characterizations

Screening of LPS-binding peptides using a phage display method has been reported in several studies [11] [22] -[24] . The major concern in those studies was to have insufficient enrichment during rounds of biopanning (affinity selection) where leads to having final phage clones with no consensus sequences [11] [24] and/or low affinity clones. In this study, some factors were carefully considered when conducting the experiment. Those factors were: using 35 mm Petri-dish plates to substitute microtiter plates for LPS immobilization, prewashing out the phages which bind to Petri-dish surface and BSA, increased biopanning to four rounds, ensuring the application of sterile techniques, and including the use of aerosol-resistant tips. Moreover, three biopanning experiments against different LPS targets (LPS-B, LPS-C, and LPS-D) were carried out at the same time to minimized the use of reagents and handling variations.

Figure 1. LPS of O-antigen B, C, and D group using modified PCP extraction.

After four rounds of biopanning procedures, a total of 56 phage peptides binding the three LPS targets were randomly selected and identified by their DNA sequences. Table 2 gives a summary of all consensus peptides found in three experiments, and their frequency in the selected phage pools. In LPS-B biopanning, two peptides out of 15 total phage clones sequenced were each encoded by multiple clones. Similar results were obtained from LPS-C and LPS-D experiments. Out of 22 clones sequenced in LPS-C biopanning, phage C4-8 and C4-9 both have consensus sequences clones and their frequencies were 68.2% and 13.6% respectively. Among all three biopanning experiments, phage D4-2 and D4-5 in LPS-D biopanning (Table 2) showed the lowest consensus sequence frequencies of 42.1% and 10.5%. Interestingly, in Table 2, phages B4-1, C4-8, and D4-2 contained the same set of peptide sequences, but they were biopanned from different LPS targets. Phage B4-16 and C4-9 also contained identical peptides and were biopanned from different LPS extractions. This information shows that there might be common regions on three LPS structures to promote binding of these identical peptides. It also shows that the four rounds of biopanning were sufficient to select high frequency peptide binders not only within each LPS affinity selection, but also among three LPS targets. However, having high frequencies of consensus peptide sequences only exhibited successful biopanning procedures. The actual binding capacities of the phage peptides to the LPS and whole cells were investigated in more detail.

3.3. LPS and Whole Cell ELISA Screening for Phage Probes

The LPS ELISA was used to further characterize the binding specificity of identified phages. Specificity here was defined as the ability of a phage peptide to interact with a target. To determine specificity, the binding of the selected phage clones was compared to the control phage M13KE [9] . Six phages repeatedly demonstrated high affinity to isolated LPS antigens (5 - 25 folds higher) in LPS ELISA tests (Table 3). Interestingly, two sets of consensus phage peptides previously mentioned are also present in this high affinity group (note a and b in Table 3). Thus, these two peptides demonstrated a real binding capacity to the immobilized LPS-B and LPS-D. In Table 3, it is also notably shown that phage C4-22 had the highest binding (more than 25 folds higher binding) to LPS-C when compared to the control phage M13KE. Phage C4-22 was not a high frequency selected peptide. Instead, it is represented as one out of 22 clones sequenced in the LPS-C biopanning. However, this phage demonstrated the highest binding affinity in LPS ELISA tests among all other phage peptides. This finding provided evidence that the high frequency clones only indicated good affinity selection in the biopanning procedures, but the clones themselves were not guaranteed to be the best phage peptides for binding. As in the report of Tanaka et al., 2008 [23] , the candidate phage peptides showed high affinity to its target without being a high frequency phage.

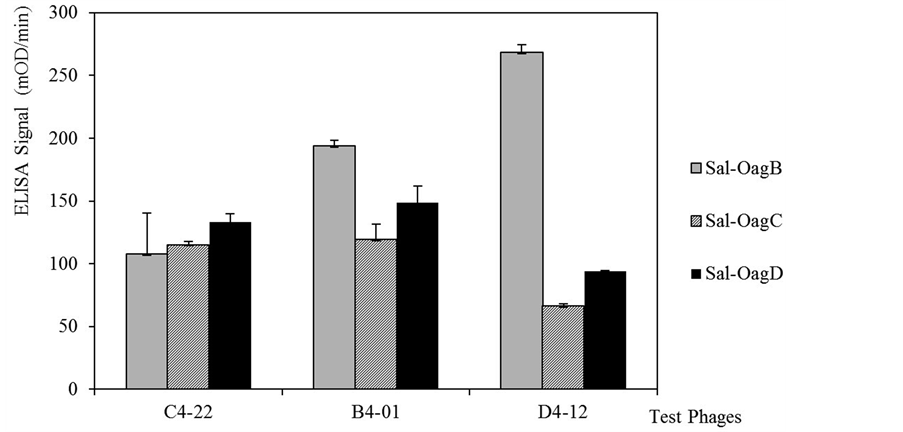

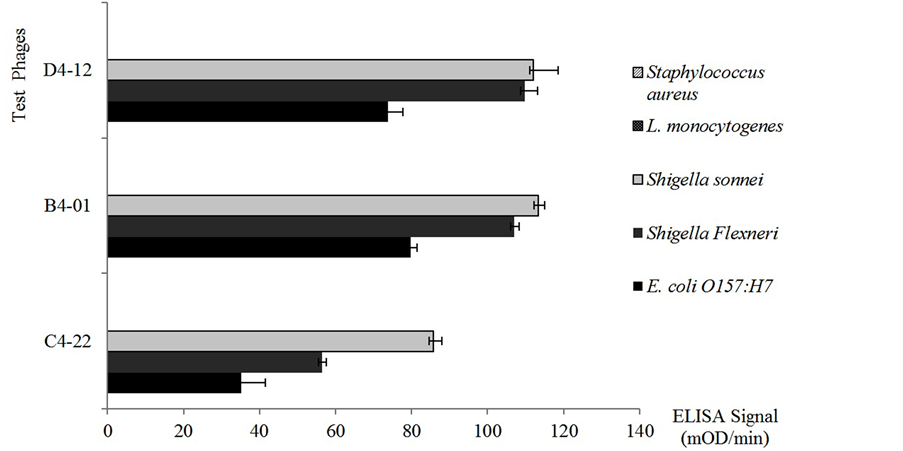

Whole cell ELISA tests were conducted to see the selective binding of phages to Salmonella cells (Figure 2) and other bacteria (Figure 3). In Brigati et al., 2004 [9] , selectivity was defined as the ability of the identified phage to preferentially interact with a select target. In our study, three phages (Phages B4-01, C4-22, and D4-12)

Table 3. Binding specificity of candidate phages in LPS ELISA.

Nine phages with the consistently higher ELISA signals than M13 phage control were selected from LPS ELISA. The results were expressed as the means ± SD of three independent measurements for each experiment. aPhage B4-1 has identical sequences as phage D4-2. The frequency of isolated this clone is 11 out of 15 in LPS-OagB biopanning. bPhage B4-16 has identical sequences as phage D4-12. The frequency of isolated this clone is 3 out of 15 in LPS-OagB biopanning. cM13 phage was M13KE control phage purchased from New England BiolLab (Ipswich, MA).

Figure 2. Three phages binding specificity by Salmonella whole cell ELISA. Final three phages were selected for affinity test to whole cells of Salmonella enterica serovars in O-antigen B, C, and D in ELISA. The baseline signals of M13KE phage to each Salmonella test group was deducted. Error bar = standard deviation of three independent measurements for each experiment.

Figure 3. Three phages binding selectivity by whole cell ELISA. Three final phages were selected to test for affinity in ELISA to whole cells of Shigella sonneii, Shigella flexneri, and E. coli O157:H7, L. monocytogenes, and S. sureus. The baseline signals of M13 KE phage to each tested bacteria was deducted. The ELISA signal of three phages to S. aureus and L. monocytogenes showed zero after deduction. Error bar = standard deviation of three independent measurements for each experiment.

that demonstrated high specificity in studies were used. Binding of the phage probes were first compared within a different O-antigen group of Salmonella cells (Figure 2). Phage C4-22 had relatively equal binding signals to all three O-antigen groups of Salmonella cells when compared to the signals of phages B4-01 and D4-12. Next, the phage binding abilities to other Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria were studied (Figure 3). Gramnegative bacteria, such as Shigella sonnei, Shigella flexneri, and Escherichia coli O157:H7, were chosen because of their phylogenic relationship to Salmonella enterica in the Enterobacteriacae family. Possibly due to the same reason, three phages showed cross-reactive binding to these Gram-negative bacteria (Figure 3). When the ELISA signals in Figure 2 and Figure 3 were compared, the binding of phage C4-22 to Salmonella cells was still much higher and more comparable than to other three Gram-negative bacteria (Figure 2 and Figure 3). These results showed that phage C4-22 has better selectivity to Salmonella in O-antigen group B, C, and D than to Shigella sonneii, Shigella flexneri, and Escherichia coli O157:H7. The finding is similar to the phage VTPPTQHQ probe, which binds specifically to S. typhimurium [10] . In Figure 3, the three test phages had relatively no binding signal to the Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes in this whole cell ELISA study. Because Gram-positive bacteria have virtually no LPS content on the cell membrane, we expected to find that these three phage probes, which went through affinity selections toward LPS targets, really didn’t bind to non-LPS cells. Some may question that the whole cell ELISA signals are always so low. According to Brigati et al., 2004 [9] , Sorokulova et al., 2005 [10] , and our ELISA results, the phage ELISA signals to bacterial whole cells usually fall between 50 - 200 m OD/min when using the same filamentous phage concentration, the same amount of anti-M13 antibody and AP-PNPP system.

Phage C4-22 showed that it is the best candidate for use on the biosensor because it was consistently specific with a high level of affinity to Salmonella LPS and Salmonella whole cells. This phage also showed low specificity to other related Enterobacteriacae members such as Shigella and Escherichia coli O157:H7, and relatively no binding to Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes (Figure 3).

3.4. Biosensor Study

The phage-based ME biosensors have been successfully shown to detect various pathogens in food, such as Salmonella, and Bacillus spores with high sensitivity and specificity [2] [4] . Recently, a new detection of phagebased ME biosensor using surface-scanning coil has been demonstrated on tomato surfaces [5] .

In most of the phage biosensor investigations, a water rinse sample from food surface was normally collected and used for detection. Therefore, our ME biosensor model was set to test the Salmonella capture capacity in solutions when the solutions were loaded on phage C4-22 coated ME biosensors. Salmonella typhimurium AMES, a virulent strain in PBS buffer, was used here to mimic the micro-contaminates from a water-rinsed or liquid samples from foods. Instead of measuring resonant frequency changes of the biosensor, which has a mass change during Salmonella cells bind to phage C4-22, true Salmonella cell counts on the surface of the phage coated sensor were studied directly. This approach gave a closer view of Salmonella captured on this phage biosensor.

Test samples with different Salmonella concentrations represent foods or liquid in various micro-contamination levels. As in Figure 4, the Salmonella captured index of the control sensor showed a steady baseline of 1.92% to 2.36% in various Salmonella concentrations. This base line serves as a control due to the fact that it was only the non-specific Salmonella captured by sensors. The data of this non-specific binding of Salmonella was independent from the concentration differences of Salmonella input. It is clearly shown that on the phage coated sensors, the Salmonella capturing abilities increased while the Salmonella concentration in the test sample increased. When the Salmonella loading was at a concentration up to 5 × 108 cfu/ml, phage biosensors demonstrated maximum Salmonella binding capacity (30 times higher) when compared to the control sensors (Figure 4). In this model study, phage C4-22 coated sensor specifically captured the Salmonella cells in test samples. The data also shows that the phage sensor capture abilities dramatically decreased at the loading of a Salmonella concentration of 2 × 104 cfu/ml. According to Li et al. in 2010 [4] , the lowest sensitivity of this type of phage biosensor should be at the S. typhimurium concentration of 5 × 102 cfu/ml when detecting on tomato surfaces and measuring by resonant frequency changes. Therefore, even when the loaded Salmonella concentrations fall in the phage sensor’s low Salmonella capture range according to our cell count data, the phage sensor can detect the bacteria by resonant frequency changes to a concentration of 5 × 102 cfu/ml.

Because glycine (solution at pH 2.2) was used to break the phage-Salmonella bounds and retrieve Salmonella cells on TSA plate, our model was only able to monitor Salmonella counts down to the sample concentration of 2 × 104 cfu/ml. This is not the detection limit of this phage senor, but it is the limit of our cell counts model. The low pH solution of Glycine is harmful to some bacteria cells and sometimes has a killing effect to Salmonella cells even before the neutralization step. Therefore, the true detection limit of this phage sensor can be much lower if measuring the frequency changes on the phage sensor, which is a real time detection method demonstrated in food [4] [25] . This model helped us to study the specificity of phage C4-22 probe used on ME biosensor, and also provided data of true Salmonella counts captured by this phage biosensor.

Figure 4. Percent Salmonella binding index on phage coated sensors vs. control sensors when loaded different concentration of Salmonella. Error bars = standard deviations from three independent sensor experiments and each experiment was performed in triplicates.

4. Conclusion

In this research, we used phage display technology combined with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antigens extracted from bacterial cell surfaces of different groups of serovars to develop phage probes that bind with Salmonella enterica serovars, and demonstrated the use of the phage on rapid magnetoelastic biosensor systems as a front-line detection ligand. The modified PCP LPS extraction method enabled the use of these antigens to produce peptides that bind with the cell surface of all representative Salmonella enterica (O-antigen groups B, C, and D) tested to date. The phage clone C4-22 appears to be an ideal probe to use with rapid bio-sensor systems for real-time, in-situ detection of all relevant serovars of Salmonella in foods, due to the probe’s high specificity and sensitivity in ELISA tests and the biosensor model study. This report indicates that the LPS extraction can substitute for the use of many different whole-cell serovars and shows a phage clone that reacts with Salmonella enterica serovars in O-antigen groups B, C, and D. These findings are being applied to the construction of a biosensor that binds all Salmonella.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Whiteny Corgill and Maghan Bowser for their assistant in this project. This work was supported by the Auburn University Detection and Food Safety Center (AUDFS) and a USDA grant (USDA-2011-51181-30642A).

References

- CDC (2014) Salmonella Data Now at Your Fingertips.

http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0326-salmonella-data.html - Huang, S., Yang, H., Lakshmanan, R.S., Johnson, M.L., Wan, J., Chen, I.H., Wikle, H.C., Petrenko, V.A., Barbaree, J.M. and Chin, B.A. (2009) Sequential Detection of Salmonella typhimurium and Bacillus anthracis Spores Using Magnetoelastic Biosensors. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 24, 1730-1736. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2008.09.006

- Shen, W., Lakshmanan, R.S., Mathison, L.C., Petrenko, V.A. and Chin, B.A. (2009) Phage Coated Magnetoelastic Micro-Biosensors for Real-Time Detection of Bacillus anthracis Spores. Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical, 137, 501-506. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2009.01.027

- Li, S., Li, Y., Chen, H., Horikawa, S., Shen, W., Simonian, A. and Chin, B.A. (2010) Direct Detection of Salmonella typhimurium on Fresh Produce Using Phage-Based Magnetoelastic Biosensors. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 26, 1313-1319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2010.07.029

- Chai, Y., Wikle, H.C., Wang,

Z., Horikawa, S., Best, S., Cheng, Z., Dyer, D.F. and Chin, B.A. (2013) Design of

a Surface-Scanning Coil Detector for Direct Bacteria Detection on Food Surfaces

Using a Magnetoelastic Biosensor. Journal of Applied Physics, 114, 104504.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4821025 - Huang, S., Li, S., Yang, Q., Johnson, H., Wan, J., Chen, I., Petrenko, V.A., Barbaree, J.M. and Chin, B.A. (2008) Optimization of Phage-Based Magnetoelastic Biosensor Performance. Special Issue of Sensors & Transducers Journal, 3, 87-96.

- Hitchcock,

P.J. and Brown, T.M. (1983) Morphological Heterogeneity among Salmonella Lipopolysacch

aride Chemotypes in Silver-Stained Polyacrylamide Gels. Journal of Bacteriology, 154, 269-277. - Kido, N., Ohta, M. and Kato, N. (1990) Detection of Lipopolysaccharide by Ethidium Bromide Staining after Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis. Journal of Bacteriology, 172, 1145-1147.

- Brigati, J., Williams, D.D., Sorokulova, I.B., Nanduri, V., Chen, I., Turnbough Jr., C.L. and Petrenko, V.A. (2004) Diagnostic Probes for Bacillus anthracis Spores Selected from a Landscape Phage Library. Clinical Chemistry, 50, 1899-1906. http://dx.doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2004.038018

- Sorokulova, I.B., Olsen, E.V., Chen, I-H., Fiebor, B., Barbaree, J.M., Vodyanoy, V.J., Chin, B.A. and Petrenko, V.A. (2005) Landscape Phage Probes for Salmonella typhimurium. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 63, 55-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2005.02.019

- Guo, X. and Chen, R.R. (2006)

An Improved Phage Display Procedure for Identification of Lipopolysaccharide-Binding

Peptides. Biotechnology Progress, 22, 601-604.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bp050315o - Nanduri, V., Sorokulova, I.B., Samoylov, A.M., Simonian, A.L., Petrenko, V.A. and Vodyanoy, V. J. (2007) Phage as Molecular Recognition Elements in Biosensors Immobilized by Physical Adsorption. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 22, 986-992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2006.03.025

- Olsen, E.V., Sorokulova, I.B., Chen, I.H., Barbaree, J.M. and Vodyanoy, V.J. (2006) Affinity-Selected Filamentous Bacteriophage as a Probe for Acoustic Wave Biodetectors of Salmonella typhimurium. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 21, 1434-1442. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2005.06.004

- Westphal, O. and Jann, K. (1965) Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides. Extraction with Phenol-Water and Further Applications of the Procedure. Methods in Carbohydrate Chemistry, 5, 83-91.

- Ding, H.F., Nakoneczna,

I. and Hsu, H.S. (1990) Protective Immunity Induced in Mice by Detoxified Salmonella

Lipopolysaccharide. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 31, 95-102.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00222615-31-2-95 - Kroll, J.J., Eichmeyer, M.A., Schaeffer, M.L., Harris, D.L. and Roof, M.B. (2005) Lipopolysaccharide-Based-Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Experimental Use in Detection of Antibodies to Lawsonia intracellularis in Pigs. Clinical and Diagnostic Lab Immunology, 12, 693-699.

- Rezania, S., Amirmozaffari, N., Tabarraei, B., Jeddi-Tehrani, M., Zarei, O., Alizadeh, R., Masjedian, F. and Zarnani, A.H. (2011) Extraction, Purification and Characterization of Lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi. Avicenna Journal of Medical Biotechnology, 3, 3-9.

-

Goldman, R.C. and Leive, L. (1980) Heterogeneity of Antigenic-Side-Chain Length

in Lipopolysacchari

de from Escherichia coli 0111 and Salmonella typhinurium LT2. European Journal of Biochemistry, 107, 145-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04635.x - Jann, B., Reske, K.

and Jann, K. (1975) Heterogeneity of Lipopolysaccharides. Analysis of Polysaccha

ride Chain Lengths by Sodium Dodecylsulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophore. European Journal of Biochemistry, 60, 239-246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb20996.x - Palva, E.T. and Makela,

P.H. (1980) Lipopolysaccharide Heterogeneity in Salmonella typhimurium Ana

lyzed by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate/Polyacrylamide Electrophoresis. European Journal of Biochemistry, 107, 137-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04634.x - Maripandi, A. and Al-Salamah A.A. (2010) Analysis of Salmonella enteritidis Outer Membrane Proteins and Lipopolysaccharide Profiles with the Detection of Immune Dominant Proteins. American Journal of Immunology, 6, 1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.3844/ajisp.2010.1.6

- Kim, Y., Lee, C., Chung, W., Kim, E., Shin, D., Rhim, J., Lee, Y., Kim, B. and Chung, J. (2005) Screening of LPS-Specific Peptide from a Phage Display Library Using Expoxy Beads. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 329, 312-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.3844/ajisp.2010.1.6

- Tanaka, T., Kokuryu, Y. and Matsunaga, T. (2008) Novel Method for Selection of Antimicrobial Peptides from a Phage Display Library by Use of Bacterial Magnetic Particles. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 74, 7600-7606. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00162-08

- Matsumoto, M., Horiuchi, Y., Yamamoto, A., Ochiai, M., Niwa, M., Takagi, T., Omi, H., Kobayashi, T. and Suzuki, M. (2010) Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Peptide Obtained by Phage Display. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 82, 54-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2010.04.002

- Chai, Y., Horikawa, S., Wikle, H.C. and Chin, B.A. (2013) A Surface-Scanning Coil Detector for Real-Time, in-Situ Detection of Bacteria on Fresh Food Surfaces. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 50, 311-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2013.06.056

NOTES

*Corresponding author.