Open Journal of Modern Linguistics

Vol.4 No.1(2014), Article ID:42890,22 pages DOI:10.4236/ojml.2014.41008

Attitudes of University Students to Some Verbal Anti-Sexist Forms1

Mercedes Bengoechea, José Simón

Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain

Email: mercedes.bengoechea@uah.es, josef.simon@uah.es

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 15 October 2013; revised 20 November 2013; accepted 28 November 2013

ABSTRACT

After more than two decades of non-sexist linguistic policies in Spain, a survey was carried out to evaluate the positive or negative attitude of almost 500 students from two Madrid universities to the most controversial verbal forms advocated in Spanish non-sexist linguistic policies: 1) the use of @ (as in alumn@s [students]); 2) the use of dual gender (as in alumnos y alumnas [studentsmasc and students-fem]); 3) the use of feminine terms for some women’s professional titles and occupations (i.e. ingeniera [engineer-fem], bedela [caretaker-fem], arquitecta [architect-fem], médica [physician-fem], aparejadora [quantity surveyor-fem], gerenta [manager-fem], perita [expert-fem], cancillera* [chancellor-fem]); 4) the use of non-sexed collective nouns (as in profesorado [teaching staff]). Our aims were to know to what degree these resources were accepted by highly-educated young people, whether differences exist between the attitudes of men and women with respect to these forms, and which of these uses was the best accepted and which the least. Various examples of these non-sexist uses were presented to university students, who were asked to make a pronouncement on the feeling which these gave them or whether they used them. Our study concluded that the @ symbol and collective nouns are widely accepted among the student community. The dual gender seems to be also accepted, although greater vacillation was seen and sometimes the levels of rejection or indifference are higher. Nevertheless, of the four uses studied, the one which appears to provoke the greatest hesitation, vacillation or even opposition is the use of the feminine for some names of professions. In general, the number of female students in favour of the four features studied exceeds the number of male students.

Keywords:Non-Sexist Linguistic Policies; Attitudes to Non-Sexist Language Reform; Gender and Spanish

1. Introduction: Linguistic Attitudes and Policies

The recommendations for non-sexist use of Spanish summarised by Pauwels (1998), Nissen (2002) and Bengoechea (2008) have been accompanied in Spain by a series of rules and regulations—among them an organic law—which initially encouraged and subsequently obliged the use of non-sexist language in various fields, basically the government/legal field and the media. This phenomenon can therefore be considered to be a fully fledged case of linguistic policy, which we have described as being in need of effective means of implementation (Bengoechea, 2011).

One of the guiding factors in determining the success or failure of linguistic policies is the attitude of the linguistic community to which these policies are aimed, where “attitude” is understood to mean “a disposition to react favourably or unfavourably to a class of objects” (Sarnoff, 1970: p. 279). As far as we are aware, only Nissen (1991, 2013) has attempted to measure the acceptance in Spain of the anti-sexist reforms proposed2, something which has been carried out for Australian English and German (Jaehrling, 1988) or French (Schafroth, 1993; van Compernolle, 2008, 2009). For this reason, we set out to evaluate this aspect by undertaking a study of the attitude of students from two Madrid universities to the most controversial verbal forms advocated in Spanish anti-sexist linguistic policies.

Three components are usually distinguished in attitudes: the cognitive, affective and readiness for action (Edwards, 1982). The component which we were most interested in detecting in university students’ attitudes was the affective aspect, i.e. the emotions the language variety produces, measured on a rejection-approval scale. One of the forms of revealing such emotions is to turn to psychometric questionnaires, such as the Likert scale (1932). In spite of its limitations (Potter & Wetherell, 1987) and the difficulty of obtaining objective interpretation, the scales which measure the degree of emotion and attraction felt for a language variety are, for relevant sociolinguists (Baker, 1992; Garret et al., 2003; Garrett, 2010), basic elements when defining individual or community attitude towards a language variety (Ager, 2001: p. 132). Since they provide a certain degree of reliability (Oppenheim, 1992: p. 200), especially when measuring the intensity of attitudes (Henerson et al., 1987: p. 86), we turned to this type of psychometric scale as our methodology.

Given that surveys of attitudes provide indicators of “current community thoughts and beliefs, preferences and desires” (Baker, 1992: p. 9), we started from the hypothesis that if, after over twenty years of non-sexist linguistic policies in Spain, the attitudes of the university community were resistant to non-sexist forms, Spanish non-sexist linguistic policies would have been a real failure.

2. The Most Controversial Recommendations for Non-Sexist Use of Spanish

Some of the first suggestions for non-sexist alternatives to certain uses of Spanish were issued by the Council of Europe in 1986 and by UNESCO in 1990. Since that time recommendations have followed for alternative uses to the dominant and rocentric and sexist uses from the European Parliament (2008) and from various central and regional Spanish governments, equality agencies, trade unions, feminist associations, large corporations and political institutions, as well as individual researchers. The great majority of these guidelines have been critically reviewed by Guerrero Salazar (2007).

Bearing in mind that Spanish is a language with two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine3, where the masculine gender is “unmarked”, i.e. allegedly capable of signifying not only masculine elements, but also feminine ones, and since gender has been defined as “the grammatical accident which serves to indicate the sex of people” (Real Academia Española, 1931: p. 10), all anti-sexist recommendations have coincided on two elements: their emphasis on designating occupations, professional titles and posts in the feminine when their holders are female, and the abandonment of the so-called “inclusive masculine”, i.e. the masculine form of terms with sexual differentiation used with the intention of including women and men (e.g. alumnos [students], covering alumnas [female students] and alumnos [male students]). To avoid the use of inclusive masculine nouns, the recommendations propose the use of collective, abstract or metonymical nouns (alumnado [body of students]), or the masculine and feminine forms in full (alumnas y alumnos [female students and male students]) or abbreviated using slashes (alumnos/as) or hyphens (alumnos, -as).Over the last decade, the use of the @symbol has become popular as a symbol to group the feminine and masculine endings (alumn@s for “alumnas y alumnus”), although the recommendation for its use appears in hardly any guides to non-sexist language.

The elements mentioned in the above paragraph are precisely a few of the most controversial elements of Spanish feminist reform. As occurred in other countries (Pauwels, 1998), among them France (Ager, 1996: pp. 176-182; van Compernolle, 2009: p. 35), the institutions which act as guardians of the languages did not sit idly by when faced with anti-sexist initiatives. In this case it was the Real Academia Española [Royal Academy of the Spanish Language; henceforth la Academia] which held the lead of the anti-reform crusade (Bengoechea, 2008). Not only was express pronouncement made against the use of collective, abstract or metonymical names (Real Academia Española, 2006), but until recently (Real Academia Española & Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Españolas, 2009) a marked reluctance has been shown to full acceptance of the feminisation of posts and occupations4. As late as in the 22nd edition of its dictionary (2001) there was resistance to the feminisation of 397 professional titles (among them some with a long history in the language, such as alfarera* [female potter]5). The dictionary also maintained the masculine form as the common form for men and women in many others (with examples such as cabo, soldado or canciller [corporal-masc, soldier-masc or chancellor-masc]) (Lledó, Calero, & Forgas, 2004). In addition, for the definitions of twelve designations of prestigious professional titles which have masculine and feminine forms accepted byla Academia (abogado-abogada [lawyer], aparejador-aparejadora [quantity surveyor], arquitecto-arquitecta [architect], bachiller-bachillera [secondary school graduate], concejal-concejala [councillor], edil-edila [town councillor], gerente-gerenta [manager], ingeniero-ingeniera [engineer], intendente-intendenta [manager], médico-médica [physician], perito-perita [expert] and subjefe-subjefa [deputy head]), the dictionary in its 22nd edition has incorporated examples of use referring to women only in the masculine, as can be seen in the following entry, corresponding to the word for engineer, in the 21st and 22nd editions:

ingeniero, ra.1. m. y f. Persona queprofesa la ingeniería o alguna de susramas[engineer-masc, -fem. 1. m and f. Person who practises engineering or any of its branches] (Real Academia Española, 1992).

ingeniero, ra.1. m. y f. Persona que profesa la ingeniería o alguna de sus ramas. MORF. U. t. la forma en m. paradesignar el f. Silvia esingeniero[engineer-masc., -fem. 1. m and f. Person who practises engineering or any of its branches. Morph. Also the masculine form used to designate the feminine. Silvia is an engineer-masc] (Real Academia Española, 2001).

Given the normative character of laAcademia, almost everyone who consulted the dictionary in 2009, the time when this survey was carried out, may have believed that laAcademia tended to recommend the masculine term for women in these cases6. Even if someone interpreted in this wording the acceptance by the Academia of the feminine and masculine forms to refer to women, they might feel a greater inclination to use the masculine form, as one of the daily newspapers with the purist attention to the language, ABC, has done, opting for the masculine forms for the professional titles referred to on its pages.

On the other hand, la Academia has insisted in various statements and notes since 2001 on the validity of the masculine to represent both sexes and for the first time in its history it has expressly excluded from the standard the dual form (the simultaneous use of the masculine and feminine forms). Since 2005, la Academia refers to its Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas [Panhispanic Dictionary of Doubts, see note 6], where under the entry “gender” it affirms that the masculine covers both sexes. An entry taken from the corpus of Spanish of the Association of Spanish Academias is offered here as an example of erroneous use (“Decidiólucharella, y ayudar a sus compañeros y compañeras” [She decided to fight and to help her companions-masc and companions-fem]) to conclude that “here only the masculine could and should be used”. For the Diccionario Panhispánico, in addition to the dual forms, dual articles (las y los ciudadanos [the-masc and the-fem citizens]) and the @ symbol are not permissible (Real Academia Española & Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Españolas, 2005: p. 311). Additionally, non-sexed collective, abstract or metonymical nouns such as ciudadanía [citizenry] orprofesorado [teaching staff], recommended to replace generic masculine terms, were considered “artificiosinnecesarios, rebuscados e inclusoridículos; unaserie de recursoscuya consistenciasería imposible de aplicar en determinadoscontextos” [unnecessary over-elaborate, even ridiculous, contrivances; a series of devices for which the required consistency would be impossible to apply in certain contexts] (Real Academia Española, 2006: p. 308).

Just as in the case of certain anti-sexist verbal elements in France (Druon, 1999; Muray, 2000; Rey-Debove, 1998), in Spain, following la Academia, diatribes against the use of the dual form and the @ symbol can be found at newspapers and blogs7.

Therefore, because of la Academia’s conservative stance on non-sexist language, and because of its authority within the academic community, we would expect that the University’s population would also take a conservative stance and react negatively to the use of the non-sexist forms, showing a purist attitude. By purism we understand: ‘the manifestation of a desire on the part of a speech community (or some section of it) to preserve a language from, or rid it of, putative foreign elements or other elements held to be undesirable’ (Thomas, 1991: p. 12). Based on this assumption, we aimed this first survey at a sample of the university population in 2009.

3. Initial Questions

The purpose of the study was to assess to what degree young highly-educated generations accepted four of the most controversial anti-sexist verbal forms:

• the use of @;

• the use of dual gender;

• the use of feminine terms for women’s professional titles and occupations;

• the use of non-sexed collective nouns.

The question was raised as to what degree these resources were accepted by highly-educated young people. We also asked ourselves whether differences exist between the attitudes of men and women with respect to these changes. Finally, we wished to know which of these uses was best accepted and which least.

4. Methodology

A survey was designed out in which various examples of these new uses were presented to university students. They were asked to make a pronouncement on the feeling which these gave them or whether they used them.

The subjects in the study were a total of 465 students, of both sexes, from the Universidad de Alcalá de Henares-UAH (455) and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid-UCM (10), who were studying for scientific/technical and social science degrees. The reason for the unbalanced rate was simply that only a few teachers accepted our request to make the survey during their classes. We saw no reason to eliminate the 10 students of the Universidad Complutense, as both institutions are public universities located in the same geographical area.

Tables 1-3 show the distribution of the students participating in the survey and the studies for which they were enrolled:

Table 1. UAH students.

Table 2. UCM students

Table 3. Distribution of the sample by sex.

The survey had a total of fifty-three questions, of which only twenty were focused on one of the four anti-sexist verbal uses mentioned above and enable estimation of the acceptance of some of the uses being studied.

Maximum effort was put into keeping the responses free of prejudices and this effort guided the preparation of the questionnaire. Firstly, in the heading instructions, the people surveyed were told that we were “studying the habits and attitudes of the university community to new social and verbal phenomena”, although our interest centred exclusively on evaluating their attitude to the linguistic uses related to the feminist reform. This same reason explains why thirty-three remaining, unfocused, questions were included in the questionnaire, “blurring” the real objective of the survey.

5. Data Analysis

We have analysed the data grouping the questions in accordance with the anti-sexist use to which they refer. The presentation of the results follows in the same form.

5.1. The Use of @

As regards the first of the phenomena studied, the use of the @ symbol to indicate dual gender, the questionnaire included two dichotomous questions, Q1 and Q2, and two with responses graduated into five levels, Q3 and Q4. The following Tables 4-7 summarise the results obtained for these four questions in percentages:

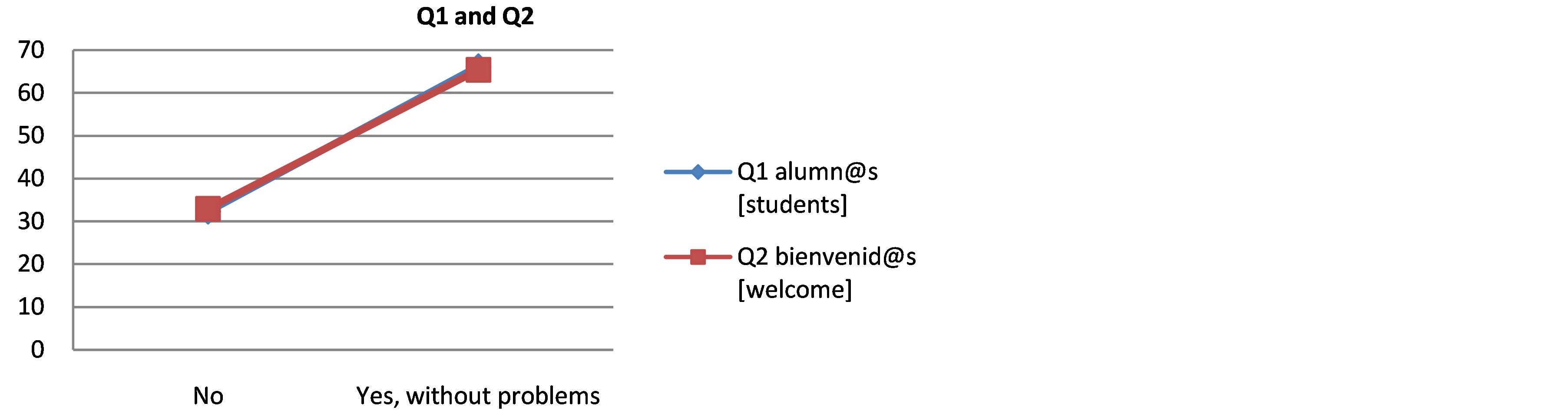

The first two questions, Q1 and Q2, show very similar results, as can be seen in Figure 1, in which the corresponding segments and ends cannot be differentiated.

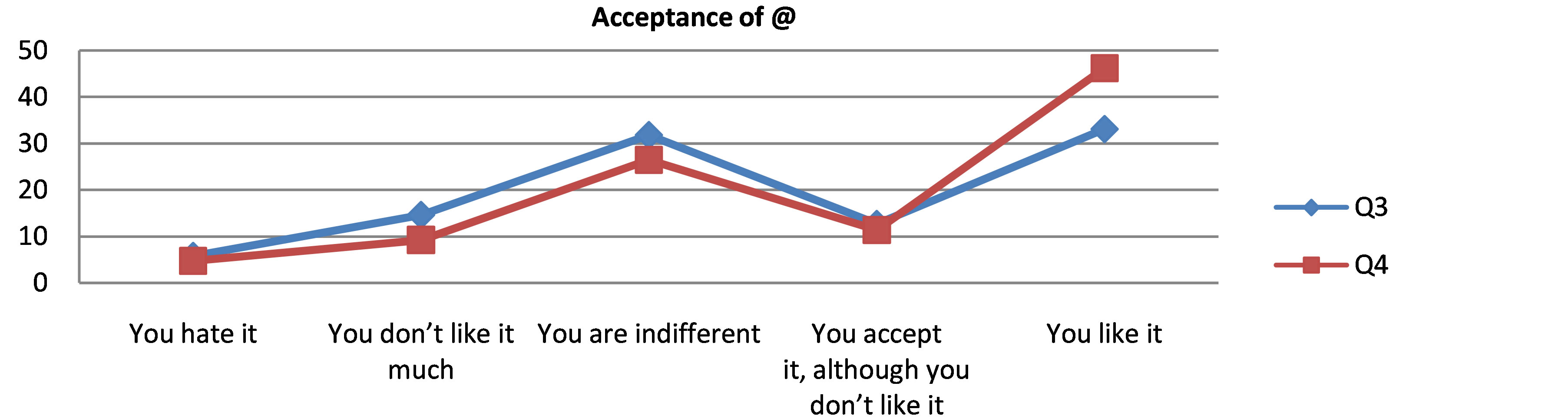

Similarly, comparing the answers with graduated responses, Q3 and Q4 (Figure 2), it can be seen that the percentages corresponding to each of the possible answers are very similar in both cases.

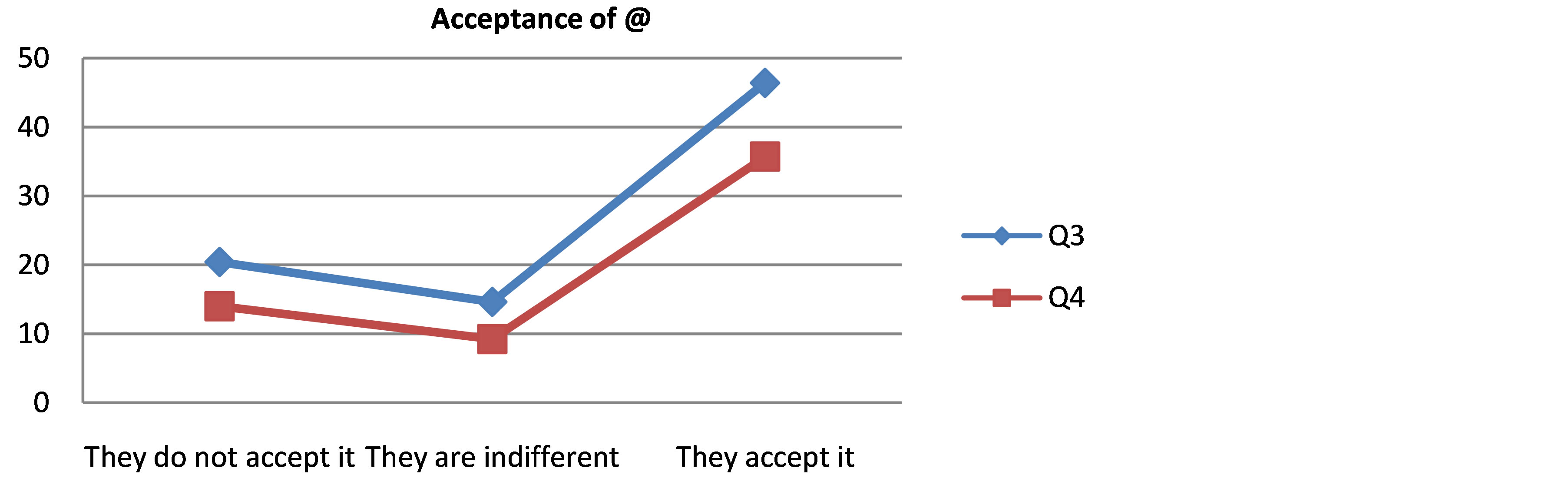

Figure 3 shows the values obtained by grouping the two negative responses to these questions (“you hate it” and “you don’t like it much”) on the one hand and the two positive responses (“you accept it” and “you like it”) on the other. The graphs for the two questions continue to be very similar, as can be seen.

Together, it can be seen that, in the four cases, the percentage of students who accept (at some level) and use expressions with the @ symbol is twice that of those who do not accept them.

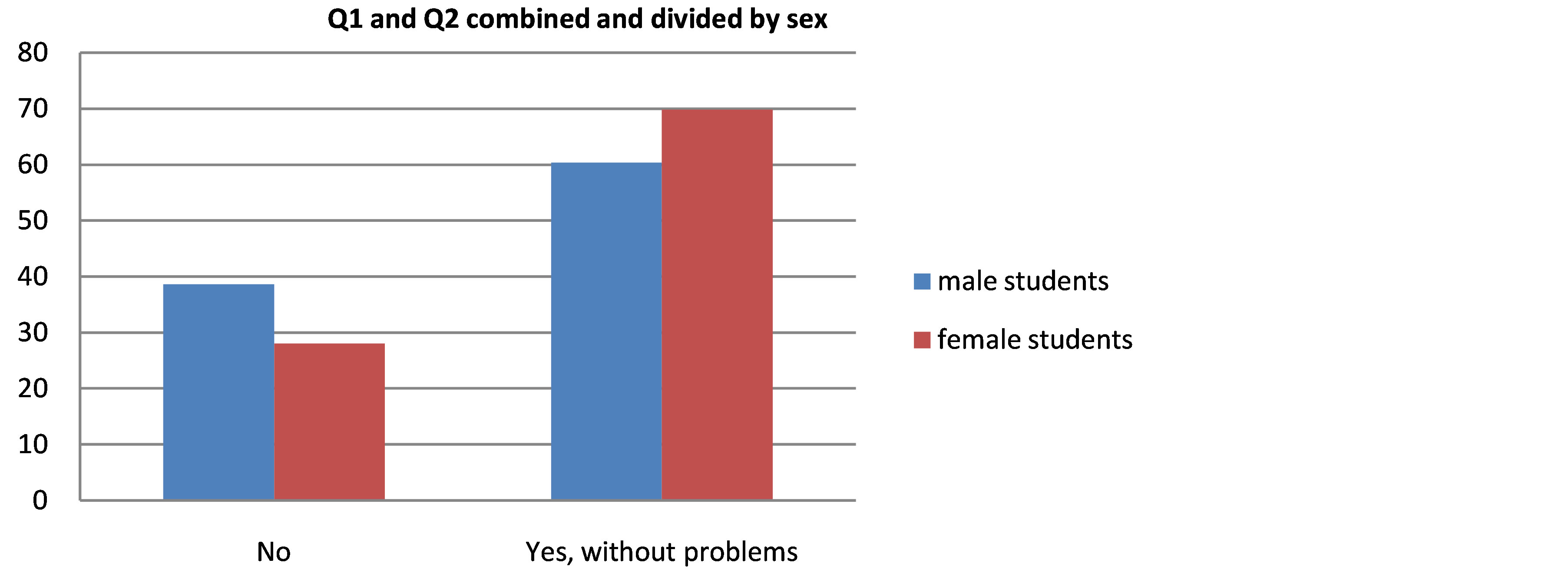

Considering the sex of the respondents, it must be highlighted that the percentage of female students who like the @ symbol is greater than that of the male students, and that a higher proportion of the latter than the former reject it. Figure 4 shows the averages of the results obtained for questions Q1 and Q2 divided by sex. The two summarised aspects can be seen in it: the percentage of students of both sexes which accept it is higher than that of those who do not accept it, and the percentage of female students who accept it is higher than that of male students.

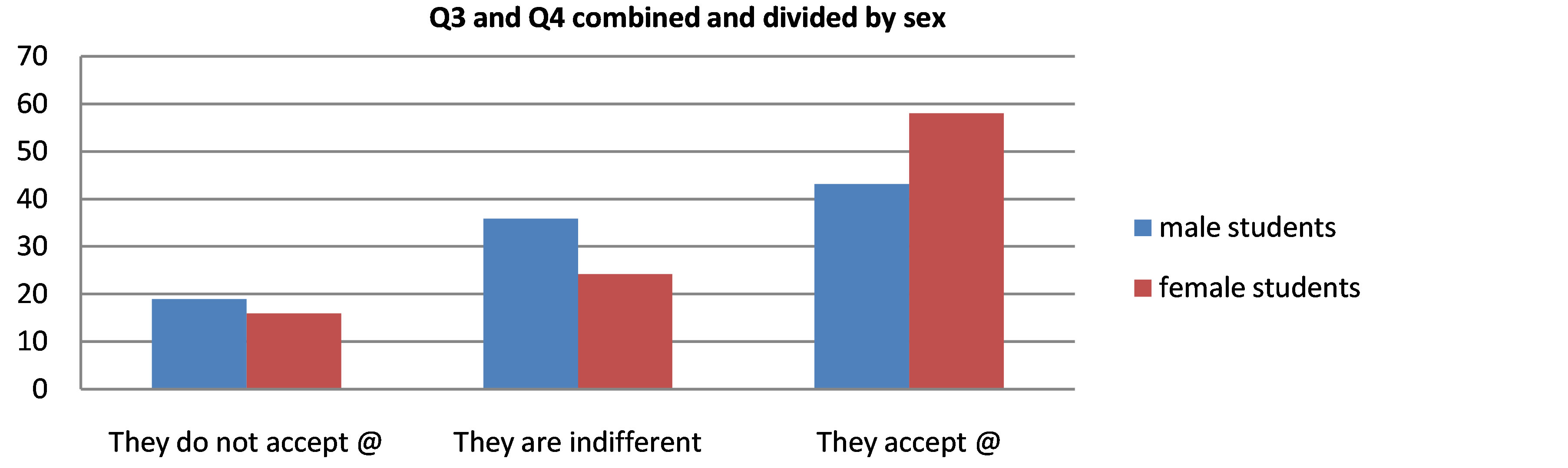

Similarly, Figure 5 shows the averages of the results obtained for questions Q3 and Q4 divided by sex. Again, the number of female students and male students who accept the @ symbol is twice as big as that of those who do not accept it. The male and female students who feel indifference exceed the number of those who do not accept it and, in turn, are less than those who do accept it. On the other hand, it can be seen again that the female students exceed the male students in responses in favour of its use, whereas the latter exceed them in the other two responses.

In short, from the results obtained it can be deduced that:

1. Students of both sexes show themselves to be mainly in favour of the use of the @ symbol; and

2. The number of female students in favour exceeds the number of male students, whereas the latter slightly exceed the former in opposition to its use.

Figure 1. Percentage of acceptance of @.

Table 4. Q1: Would you write alumn@s [students]?

Table 5. Q2: Would you write bienvenid@s [welcome]?

Table 6. Q3: What do you feel if someone writes or says Estimad@scompañer@s [Dear colleagues]?

Table 7. Q4: What do you feel if someone writes or says Estásinvitad@ a mi fiesta [You are invited to my party]?

Figure 2. Percentage of acceptance of @.

Figure 3. Percentage of acceptance of @.

Figure 4. Acceptance of @.

Figure 5. Acceptance of @.

5.2. The Use of Dual Gender

In relation to the second of the phenomena studied, the use of dual gender, the questionnaire included one dichotomous question, Q5, and four more with graduated responses: Q6, Q7, Q8 and Q9.The data obtained in the responses to all these questions is summarised (in percentages in all cases) in the following Tables 8-12.

Table 8. Q5. Would you write Esunderecho de todas y todos los españoles [It is a right of all-masc and all-fem Spanish people]?

Table 9. Q6. Do you use the expression Los estudiantes y lasestudiantes [the-masc students-masc and the-fem students-fem]?

Table 10. Q7. Does it seem right to you to use todos y todas [all-masc and all-fem] in political speeches?

Table 11. Q8. How do you feel if someone writes or says Sólotendránderecho a examen final los alumnos y alumnasquehayanasistido al menos al 80% de lasclasesprácticas [Only those students-masc and students-fem who have attended at least 80% of the practical classes will be entitled to sit the final exam]8?

Table 12. Q9. How do you feel if someone writes or says Querido/a amigo/a [Dear-masc/-fem friend-masc/-fem]?

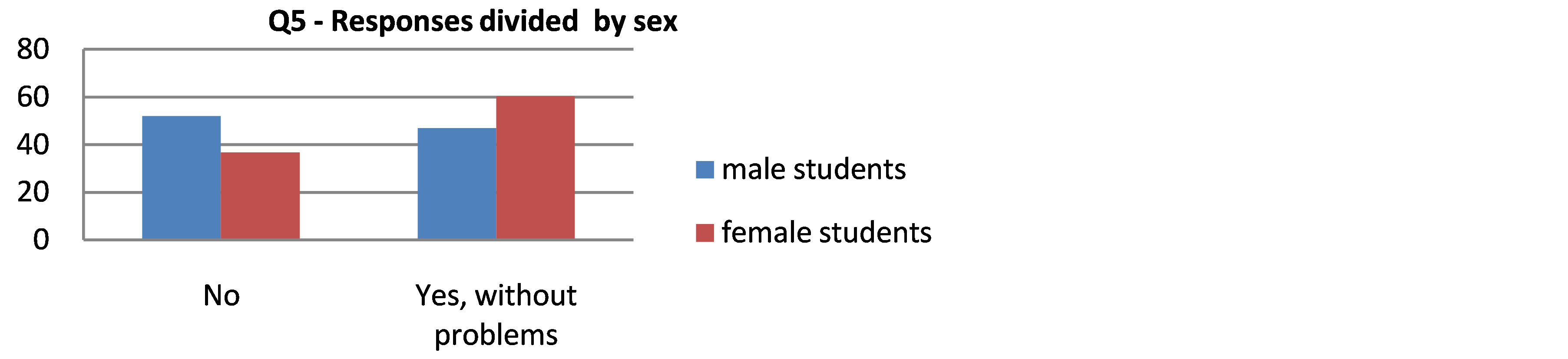

In the data obtained for question Q5, which only permits answers in favour of or against the use of dual gender, the percentage of people who stated that they would use it was twenty-five percent higher than that of people who said they would not. Likewise, it can be seen that, in this case, the female students, as occurred with the use of the @ symbol, were more inclined towards the use of dual gender than the male students. Both points can be seen in the graphs in Figure 6, in which the responses to Q5 are shown, overall and divided by sex.

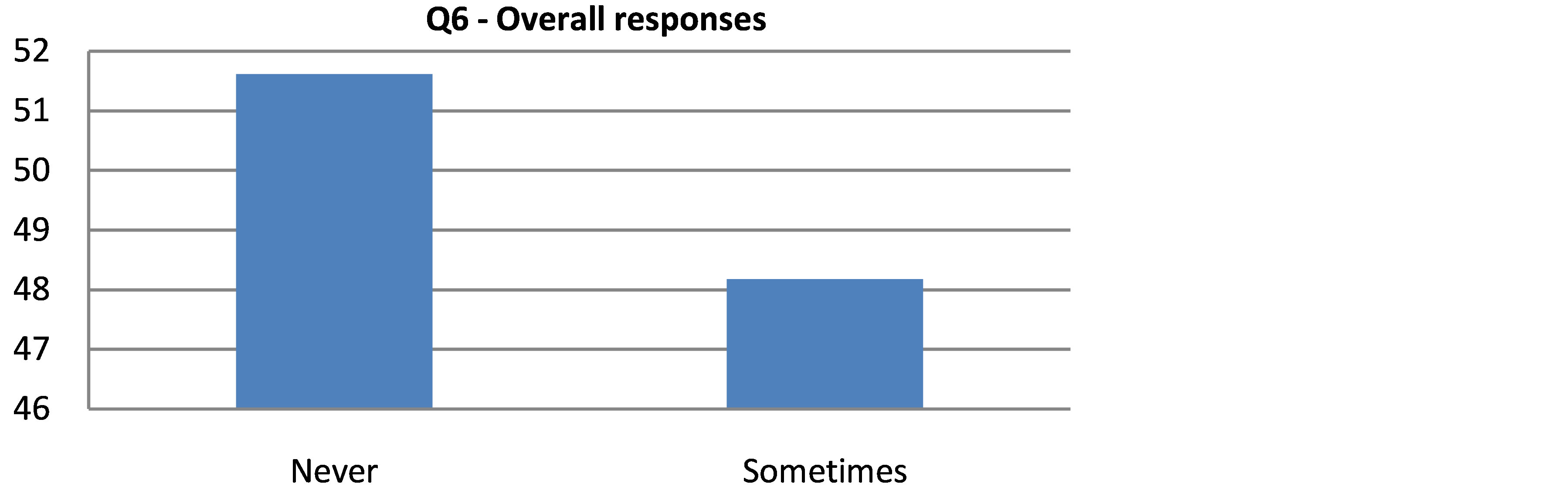

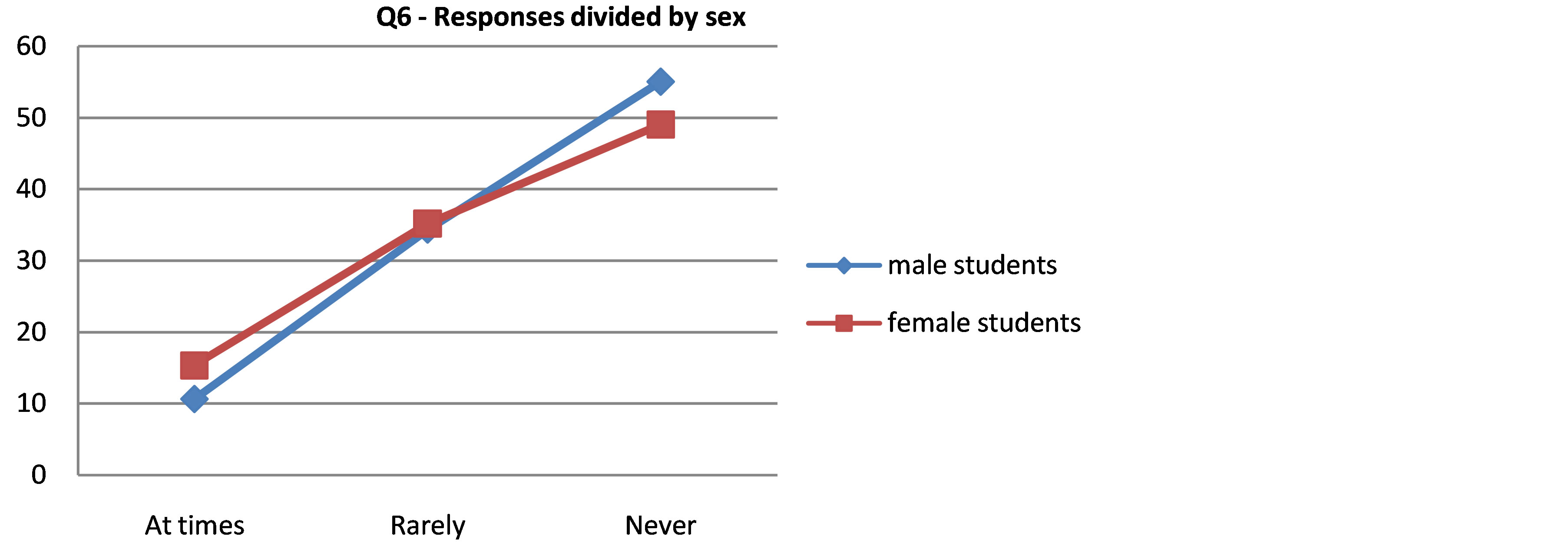

On analysing the answers to Q6 (Do you use the expression Los estudiantes y lasestudiantes [the-masc students-masc and the-fem students-fem]?), a different result was found. In this case, the overall percentage that appears not to use the dual form (those who answered ‘never’) exceeds that of the people who state that they use it. As regards the responses by sex, a greater inclination to use it by female students can be seen again. The graphs in Figure 7 show the results of the responses both grouped and divided by sex.

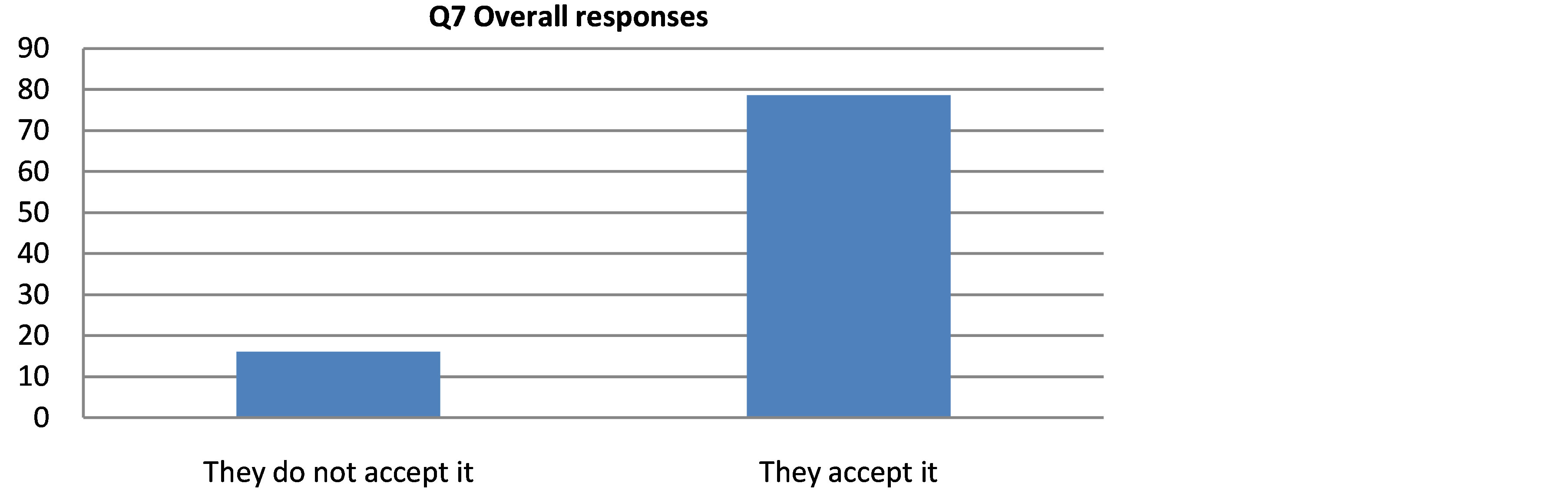

Question Q7 (Does it seem right to you to use todos y todas [all-masc and all-fem] in political speeches?) involves the expression “todos y todas” again, which appeared in Q5. Grouping the three responses in favour (“Yes, always”, “Yes, but not always” and “Only at the beginning”), it was seen that the overall percentage of people who accept its use again exceeds that of those who do not and in this case to a still greater extent (Figure 8), perhaps due to Q7 measuring the level of acceptance, while Q5 and Q6 refer to people’s own use.

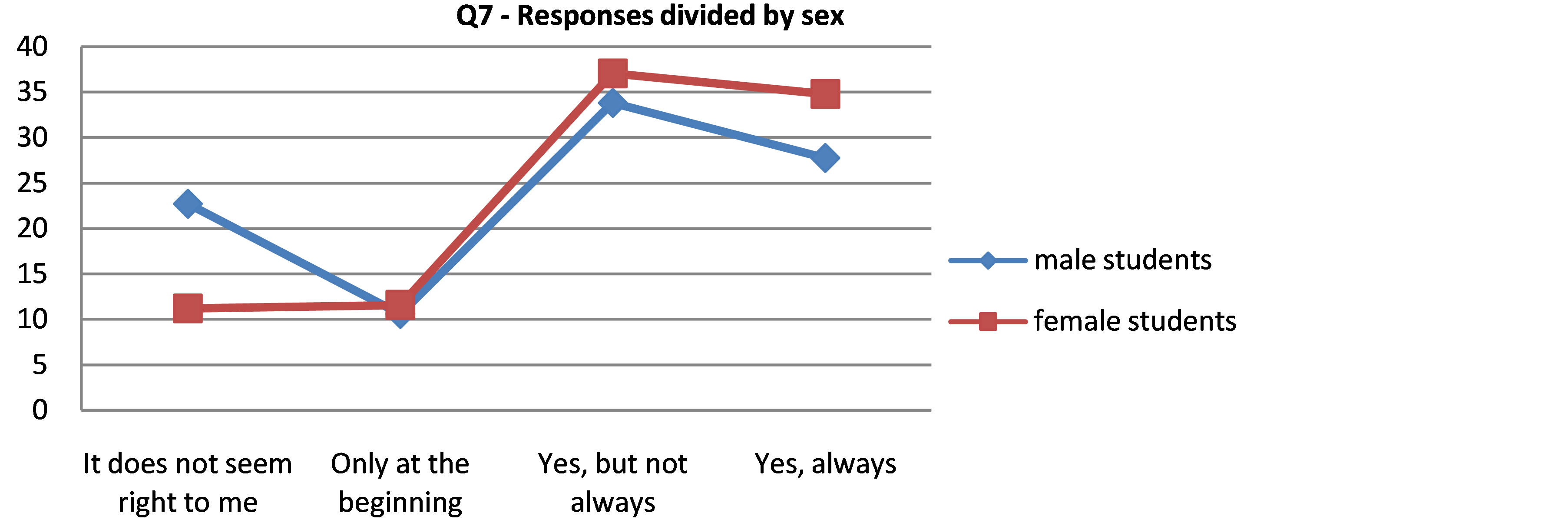

Furthermore, if the responses are broken down by sex (Figure 9), the trend which has been observed so far is seen to be maintained: the percentage of female students in favour exceeds that of the male students, while the latter exceeds the former in the “against” responses.

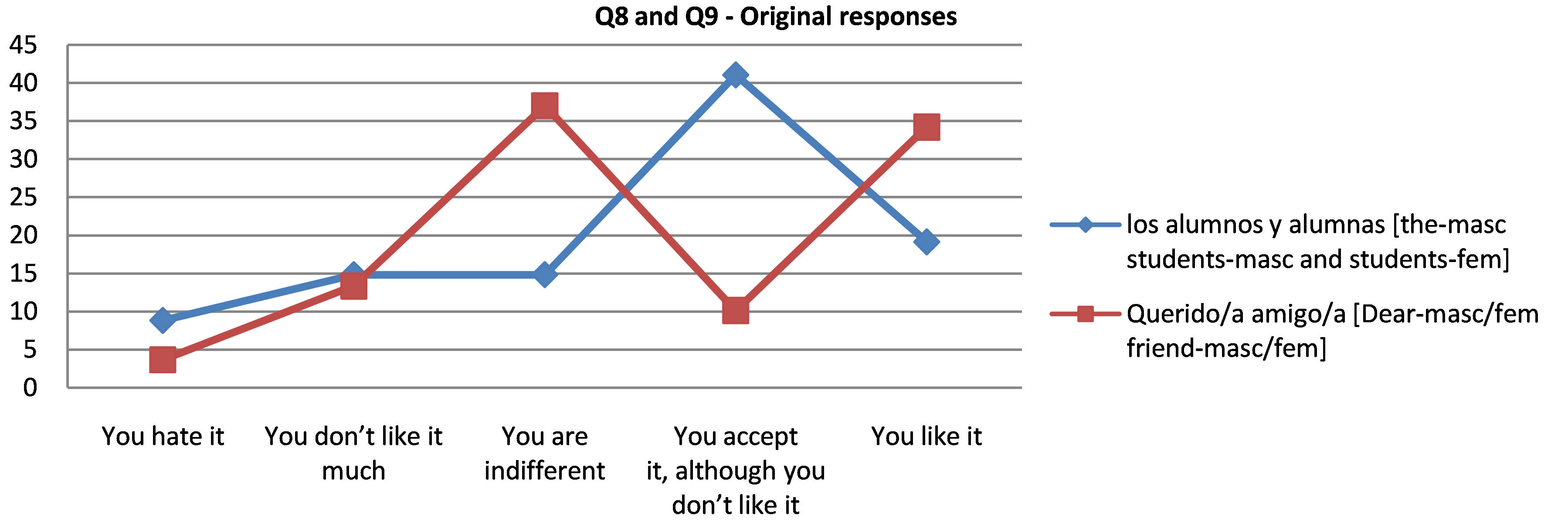

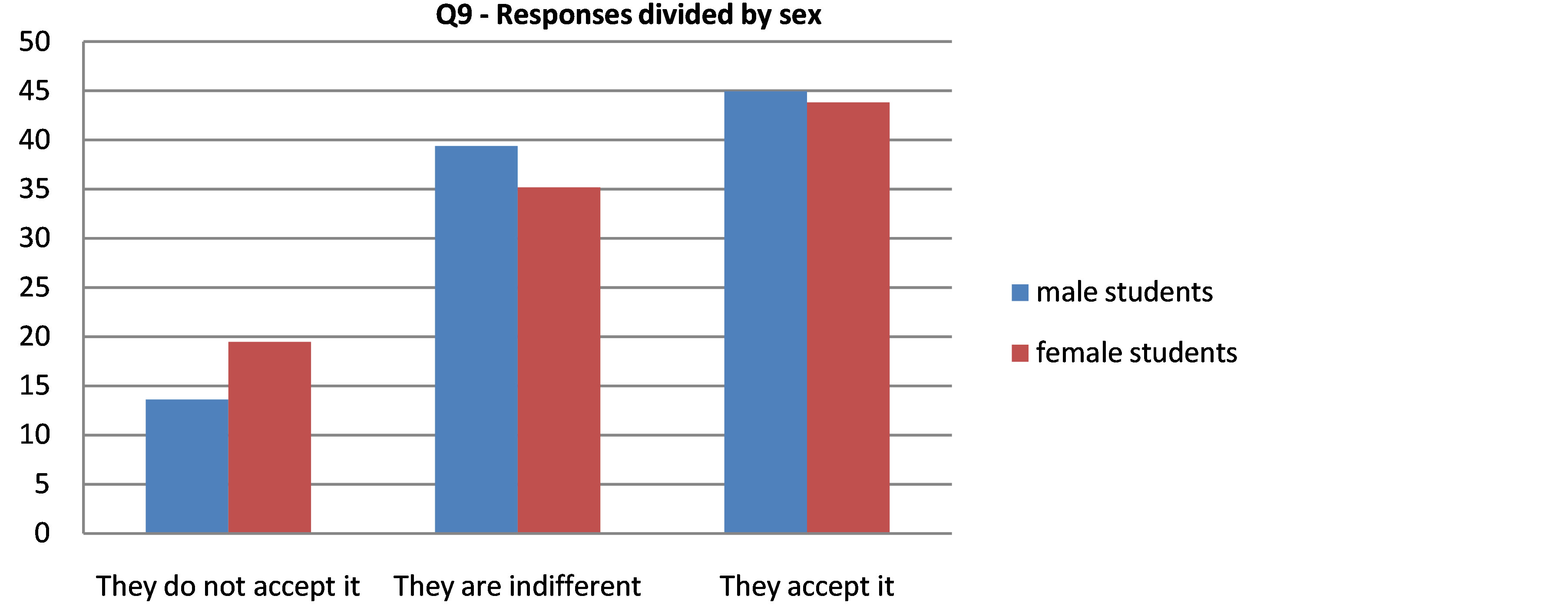

The two following questions, Q8 (How do you feel if someone writes or says Sólotendránderecho a examen final los alumnos y alumnasquehayanasistido al menos al 80% de lasclasesprácticas [Only those students-masc and students-fem who have attended at least 80% of the practical classes will be entitled to sit the final exam]?) and Q9 (How do you feel if someone writes or says Querido/a amigo/a[Dear-masc/-fem friend-masc/-fem]?), attempted to investigate the acceptance or rejection provoked by two different types of dual gender expressions: the express mention of dual gender and the use of the slash, “/”, to provide the duplication. Figure 10 graphically summarises the disparity seen in the results.

Although in the responses against the percentages are similar, opposing tendencies are seen in the responses in favour, as well as in the number of people who state themselves to be indifferent in this respect.

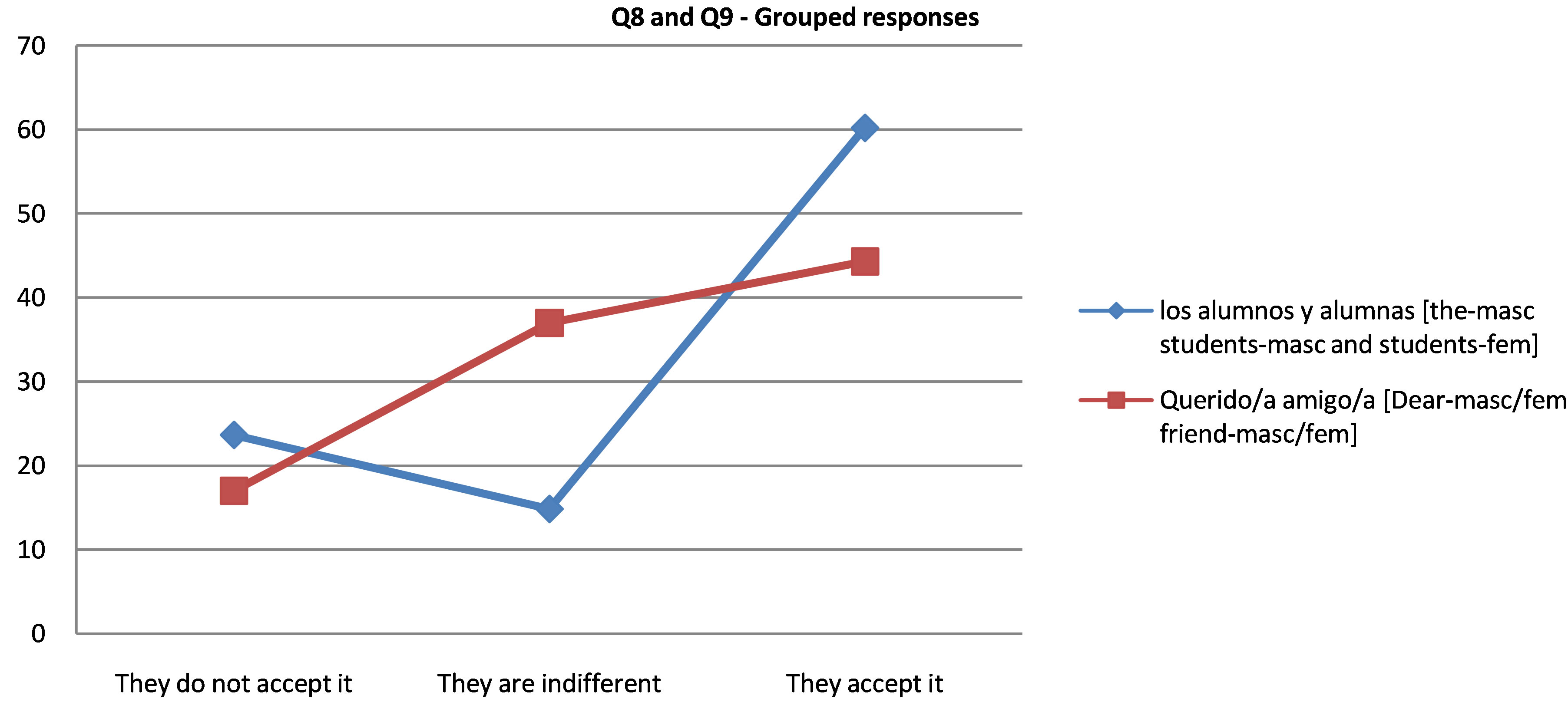

However, we can observe that the overall percentage of people who accept their use exceeds that of people who do not, as can be seen in Figure 11, showing grouped responses.

If the responses divided by sex are compared (Figure 12), a break is seen for the first time in the previous trend; namely, a greater inclination on behalf of the female students to use these expressions. The trend is maintained in Q8, but not in Q9, where the percentage of male students in favour or who state indifference is slightly higher than that of the female students, whereas the percentage of females who do not accept its use is higher than that of the males .Could this be due to the fact that the slash “masks” the feminine to some degree, as females are not represented in the full form (queridaamiga)?

Summarising the results obtained for the second of the uses studied, it can be stated that:

1. In general, students of both sexes show themselves to be mainly in favour of dual gender. However, there appears to be more hesitation than with the use of the @ symbol, as is shown when the question is asked on people’s own use of this form (Q5 and Q6) and in the fact that the percentages in favour are not twice as high as the percentages against in all the cases.

Figure 6. Q5. Would you write Esunderecho de todas y todos los españoles[It is a right of all-masc and all-fem Spanish people]?

Figure 7. Q6. Do you use the expression Los estudiantes y lasestudiantes[the-masc students-masc and the-fem students-fem]?

Figure 8. Q7. Does it seem right to you to use todos y todas[all-masc and all-fem] in political speeches?

Figure 9. Q7. Does it seem right to you to use todos y todas [all-masc and all-fem] in political speeches?

Figure 10. Q8 and Q9. What do you feel if someone writes or says…?

Figure 11. Q8 and Q9. What do you feel if someone writes or says…?

2. The number of female students in favour continues to exceed the number of male students in the majority of cases.

3. The use of the slash to duplicate the gender provokes a greater level of indifference, on one hand, and also appears to reverse the tendency seen in the previous questions, which indicated a greater willingness of female students towards these uses.

Figure 12. Q9. How do you feel if someone writes or says Querido/a amigo/a [Dear-masc/ -fem friend-masc/-fem]?

It can, then, be concluded that among our body of students, despite the use of dual gender raising more doubts and provoking greater rejection and indifference than that of the @ symbol, it is accepted by the majority.

5.3. The Use of Feminine Terms for Women’s Professional Titles and Occupations

As regards the third of the new uses studied, the use of the feminine in professional titles and occupations of women to replace the masculine, the questionnaire included a total of 9 questions: two multiple choice questions, Q10 and Q11, three dichotomous questions, Q12 - Q14 and four more with graduated responses, Q15 - Q18.

Before analysing the responses, it must be reiterated that the respective feminine forms which appear in the anti-sexist alternatives to the names of professions to which these questions allude (i.e. ingeniera [engineer-fem], bedela [caretaker-fem], arquitecta [architect-fem], médica [physician-fem], aparejadora [quantity surveyor-fem], gerenta [manager-fem] andperita [expert-fem]) are “permitted” by laAcademia (with the exception of cancillera* [chancellor-fem]), although la Academia’s dictionary appears to recommend the use of the masculine form accompanied by the feminine article in all these cases, with the exception of bedela.

The following Tables 13-21 contain the data obtained as percentages.

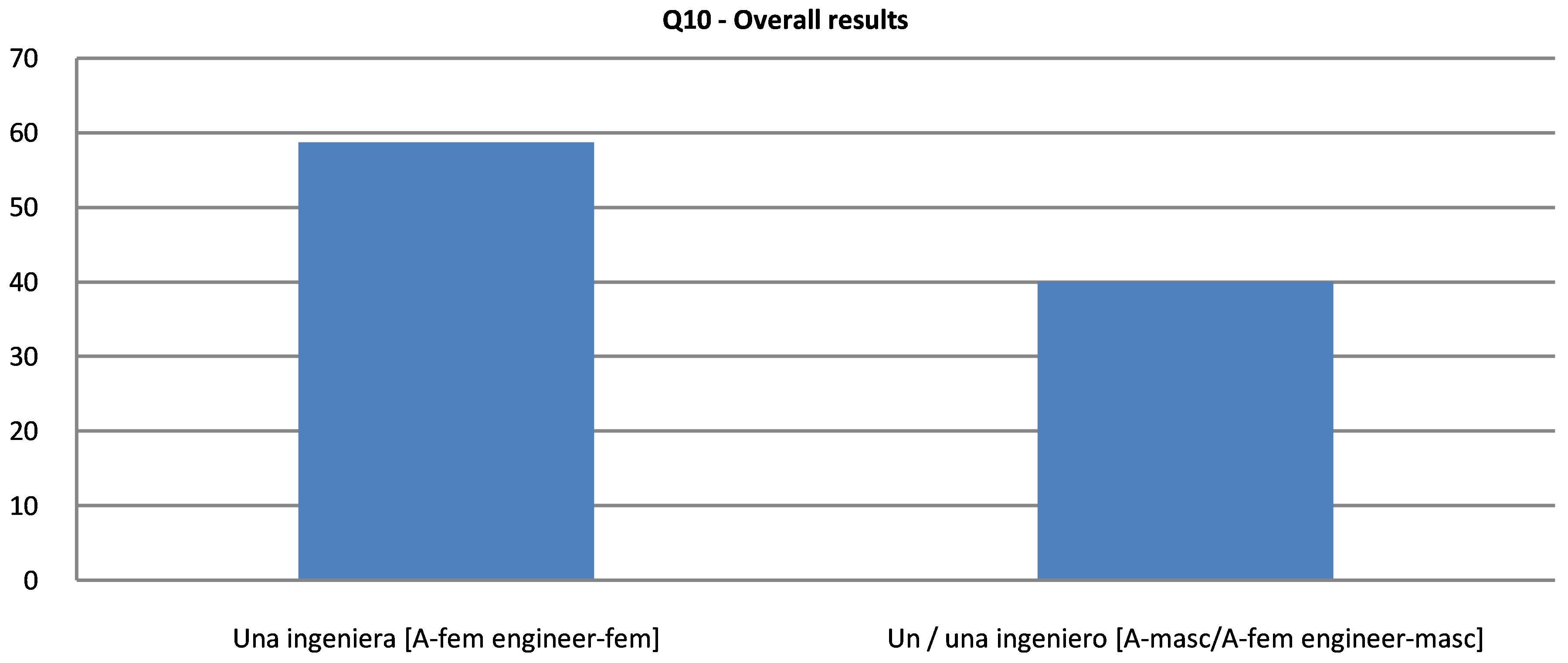

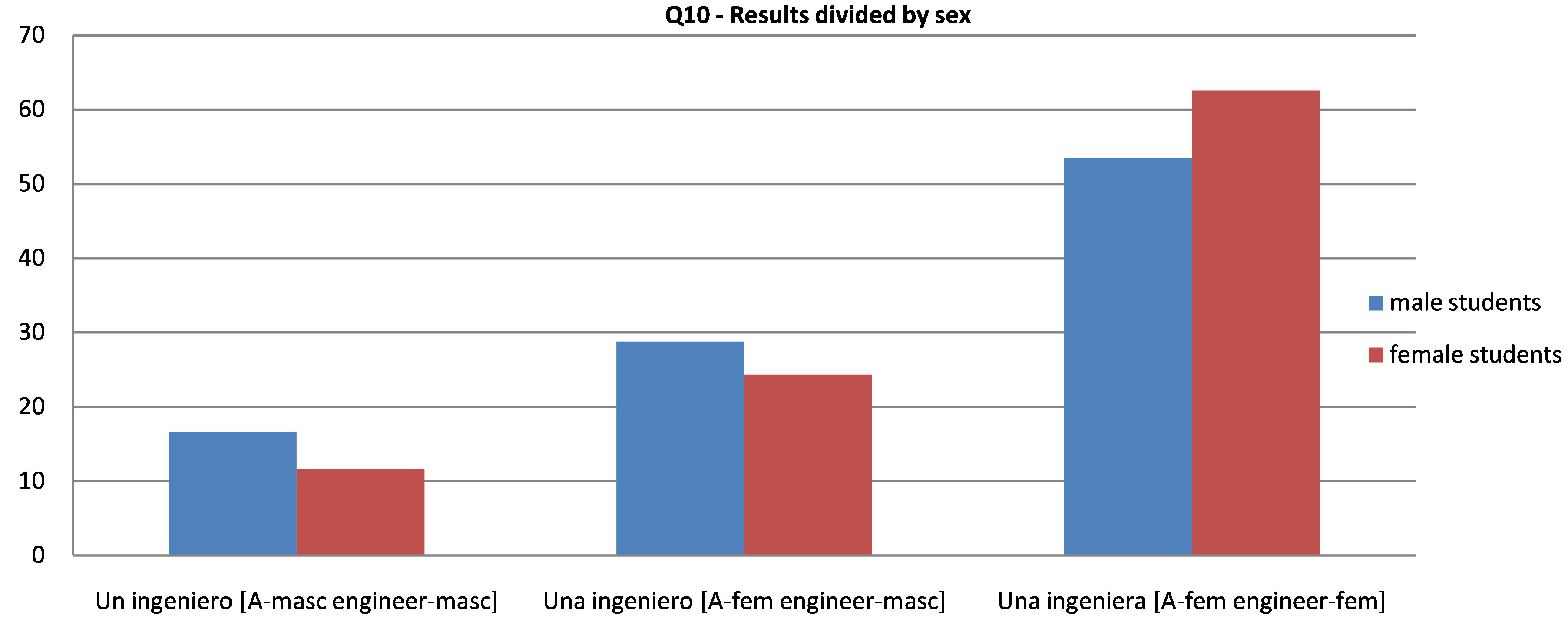

The first two questions give disparate results. While for Q10, ingeniera [engineer-fem], both sexes mainly opt for the feminine option, unaingeniera (Figure 13), the same does not occur in the following question, Q11, in which various alternatives were offered for Angela Merkel’s title (Figure 14).

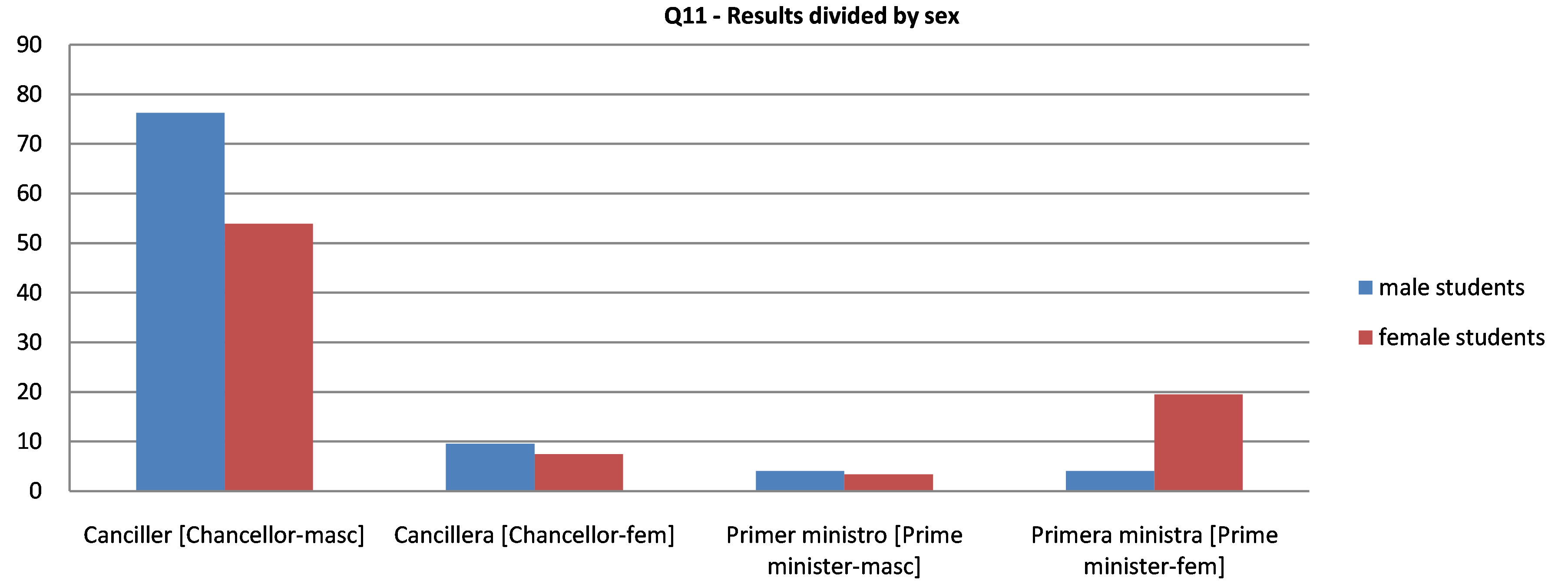

Figure 14 shows that the preferred option for Angela Merkel, both with male and female students, is canciller [chancellor-masc], the only normative response which, additionally, frequently appears in the media as the title preceding the German politician’s name. The second option for male students was cancillera [chancellor-fem], while for the female students it was primeraministra [prime minister-fem]. The cancillera option was third in the overall calculation and, contrary to what may have been expected on the basis of that seen in the preceding questions, the male students who opted for this response exceeded the female students.

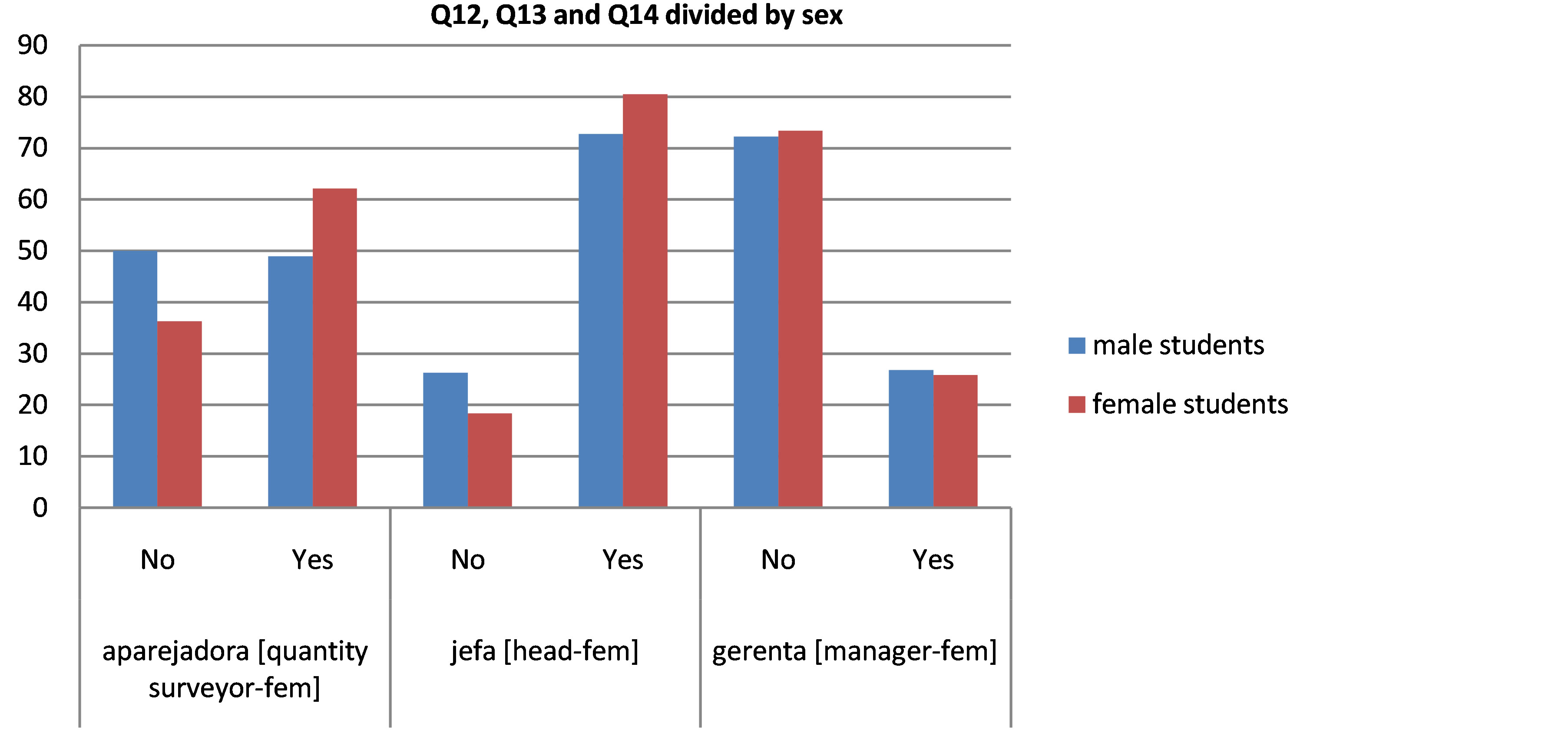

Figure 15 summarises the data relating to the three dichotomous questions, Q12, Q13 and Q14, in which they were asked whether or not they would say aparejadora [quantity surveyor-fem], jefa de secretaría [head-fem of the secretariat] and gerenta [manager-fem]. The following can be seen in the graph: on the one hand, the responses of the male and female students following the observed pattern, i.e. more males than females would not use the feminine term, except in the case of gerenta. On the other hand, while jefa de secretaría is accepted by the majority, the options for aparejadora are divided into two blocks (both almost of the same size in the case of the male students), while the use of gerenta appears to provoke generalised rejection, with percentages which are almost three times those of the responses in favour for each sex.

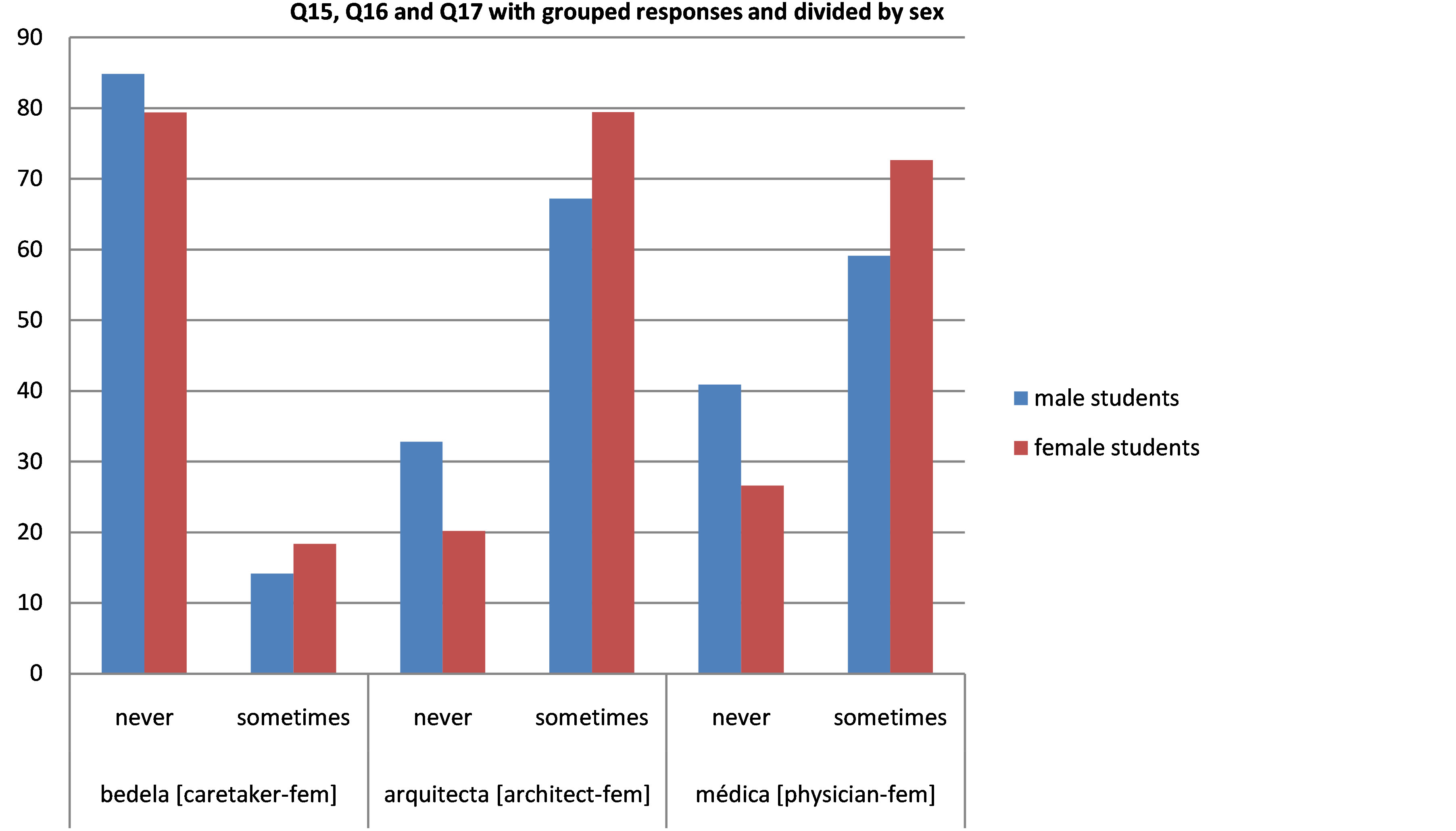

Something similar occurred with the three following questions, bedela [caretaker-fem], arquitecta [architect-fem] and médica [physician-fem], as can be seen in Figure 16, in which the favourable responses “rarely” and “sometimes” to the three questions have been grouped under the label “at some time”.

In this case the distribution of male and female students follows the general pattern:the percentage of “never”

Table 13. Q10. ¿Si tu hermana ha estudiado Ingeniería de Telecomunicaciones, es...? [If your sister studied Telecommunications Engineering she is…?]

Table 14. Q11. ¿Angela Merkel es…? [Angela Merkel is…?]

Table 15. Q12. Would you write aparejadora [quantity surveyor-fem]?

Table 16. Q13. Would you write Jefa [head-fem] of the Secretariat?

Table 17. Q14. Would you write gerenta [manager-fem]?

Table 18. Q15. Do you use bedela [caretaker-fem]?

Table 19. Q16. Do you use architecta [architect-fem]?

Table 20. Q17. Do you use médica [physician-fem]?

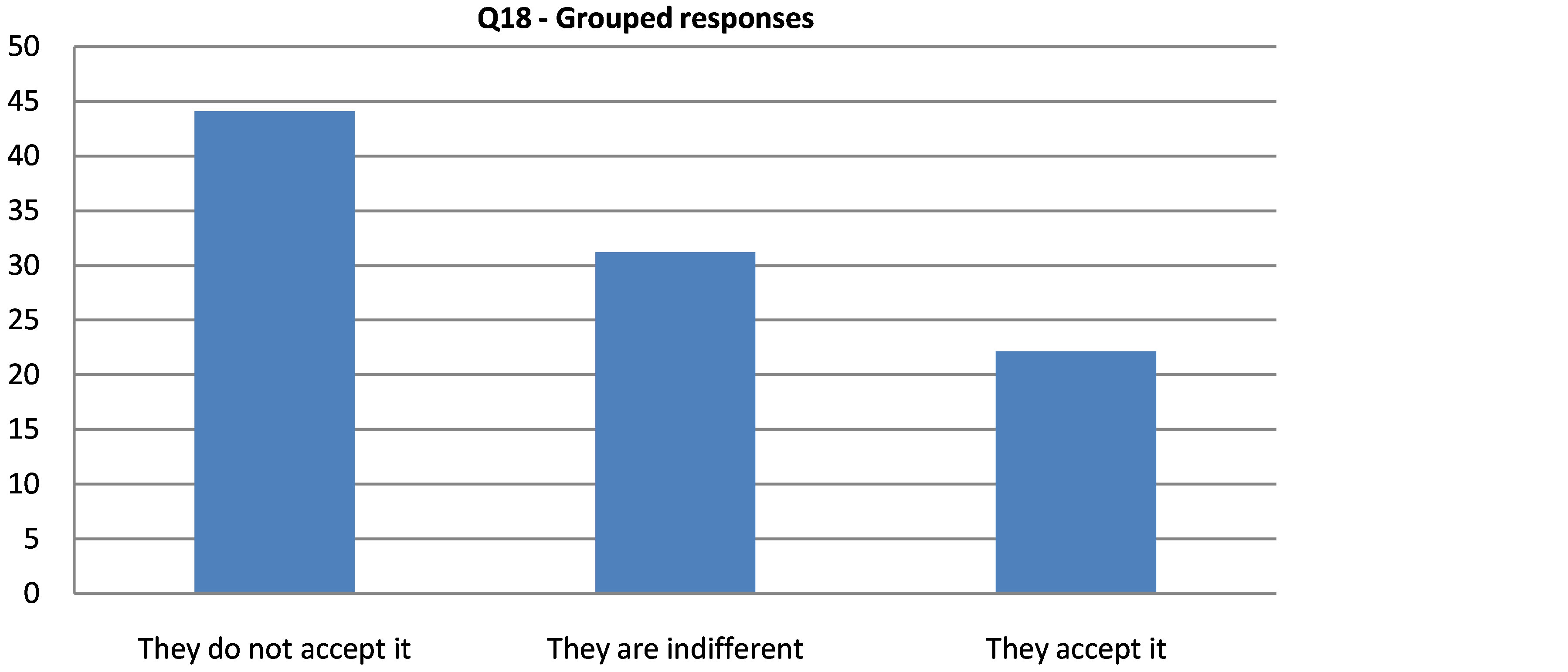

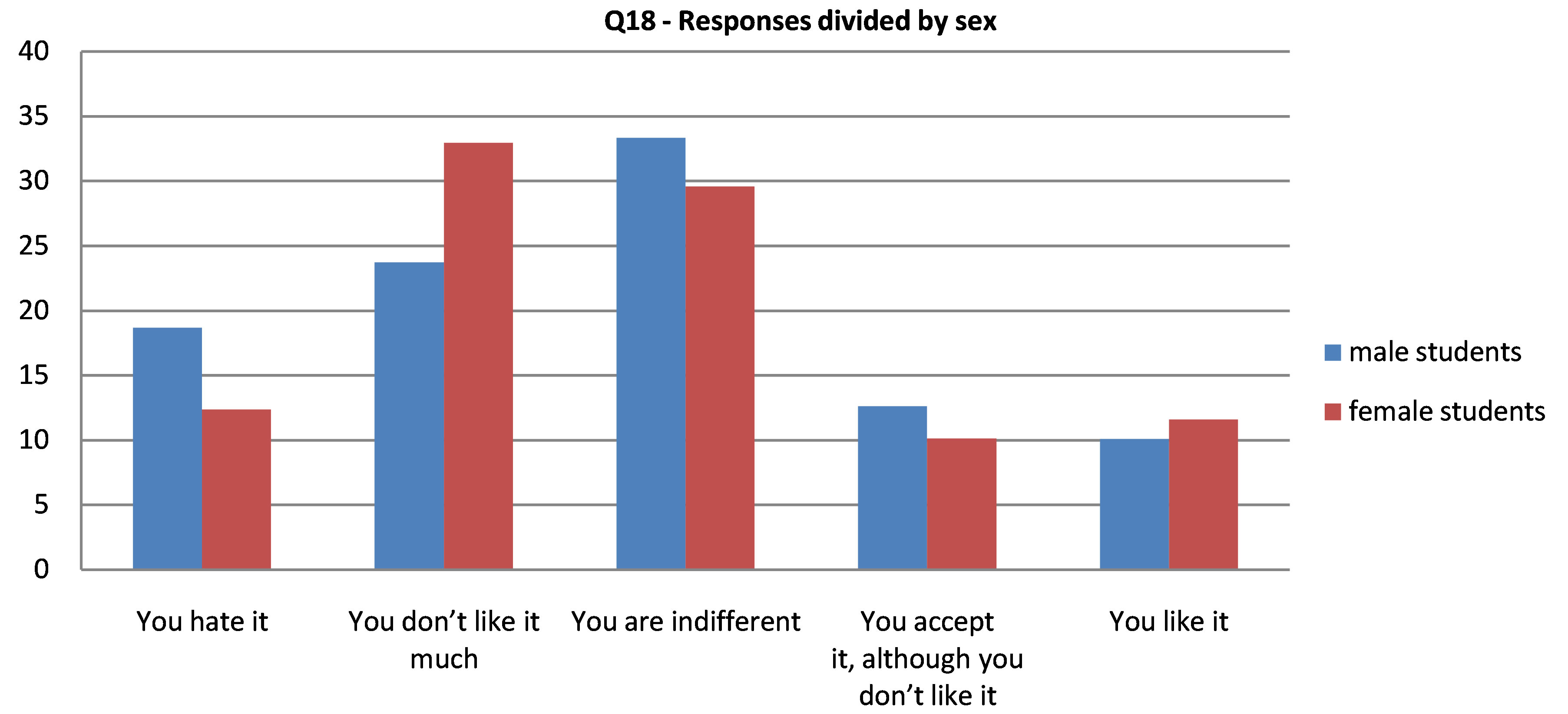

Table 21. Q18. What do you feel if someone writes or says: Tras el accidentetuvoquever mi cocheunaperita de la Compañía de Seguros [After the accident a-femexpert-fem from the Insurance Company had to see my car]?

responses is higher in the case of the males, whereas the favourable responses are higher from females. Again, while the use of arquitecta and médica is in the main acknowledged by both sexes, bedela appears to receive considerable rejection by both female and male students.

In the last of the questions relating to this third section, Q18, concerning the term perita [expert-fem], marked rejection is again seen. Grouping the responses against, on the one hand, and in favour, on the other, it can be seen (Figure 17) that the percentage of those who do not accept it is double that of those who do. In an intermediate position between the two groups are those who state indifference in this respect.

If the responses are separated by sex (Figure 18), something of a discrepancy is seen from the general trend. Although the percentage of male students who state outright rejection exceeds the number of female students (as may be expected), the female students who do not like it much exceed the male students. Likewise, the number of male students who accept it without liking it exceeds the number of female students, also departing from the pattern.

In summary, in the questions relating to the use of the feminine in professions and occupations, more disparate results occurred than in the previous cases:

1. Considering the responses overall, it was found that although the feminine designation of certain professions, such as ingeniera [engineer-fem], arquitecta [architect-fem], médica [physician-fem], jefa [head-fem] oraparejadora [quantity surveyor-fem] was fully accepted, other cases, such as gerenta [manager-fem], bedela [caretaker-fem], cancillera [chancellor-fem] or perita [expert-fem], provoked extensive rejection. The reasons which could justify these differences cannot be drawn from the questionnaire. Investigation of the possible causes would require a more detailed qualitative study.

Figure 13. Q10. ¿Si tu hermana ha estudiado Ingeniería de Telecomunicaciones, es...? [If your sister studied Telecommunications Engineering she is…?]

Figure 14. Q11. ¿Angela Merkel es…? [Angela Merkel is…?]

2. As regards the distribution by sex, in general this follows the pattern seen in previous sections, i.e. that the male students usually show greater opposition and the female students a higher rate of acceptance. However, as already indicated, in some of the terms divergences occur from this general trend, the causes of which cannot be inferred from the questionnaire either.

Figure 15. Would you write…?

Figure 16. Do you use…?

It can only be concluded, on this point, that university students in general do not appear to have a definite opinion on the use of names of professions in the feminine. There is some inclination towards their acceptance and use in the majority of cases, but reluctance to others.

5.4. The Use of Non-Sexed Collective Nouns

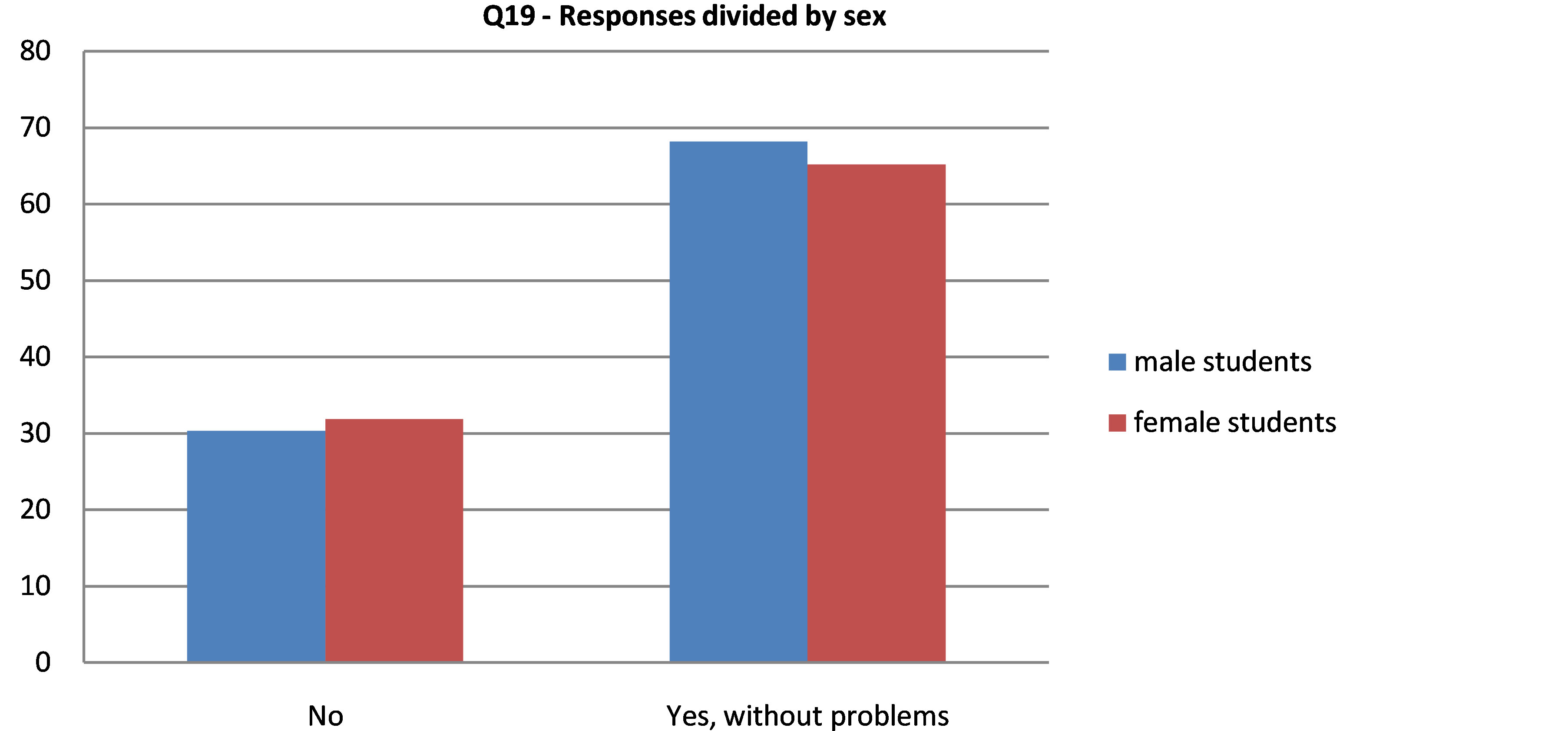

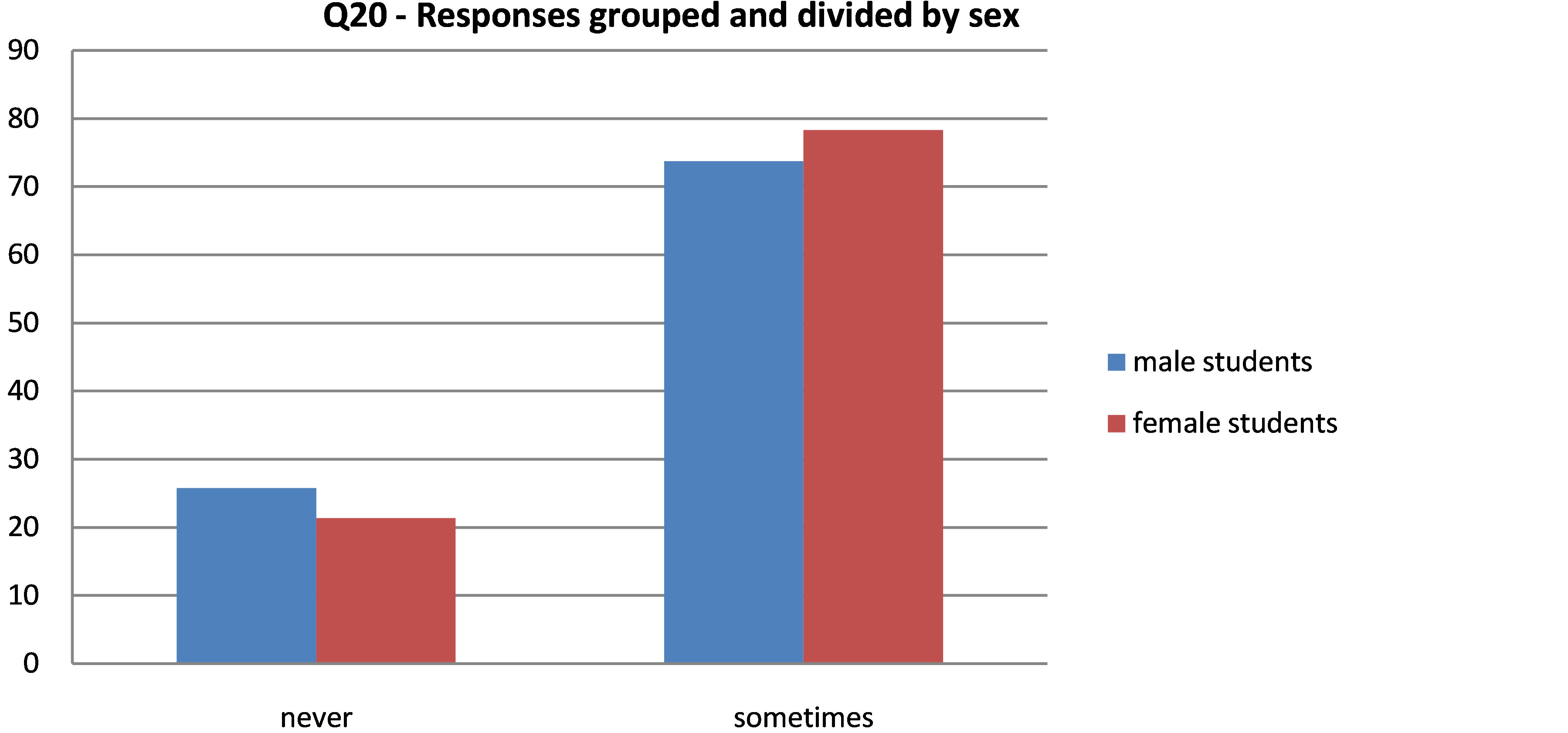

The questionnaire included two questions in this last section, one dichotomous, Q19, and one graduated, Q20. The following Tables 22 and 23 summarise the results obtained.

As can be appreciated, comparing the two tables, the results are quite similar and in both cases show clear acceptance by male and female students. Figures 19 and 20 summarise the responses to the two questions, divided by sex.

Figure 17. Q18. What do you feel if someone writes or says… perita [expert-fem]?

Figure 18. Q18. What do you feel if someone writes or says… perita [expert-fem]?

Table 22. Q19: Would you write ciudadanía [citizenry]?

Table 23. Q20. Would you write profesorado [teaching staff]?

Figure 19. Q19. Would you write ciudadanía [citizenry]?

Figure 20. Q20. Would you write profesorado [teaching staff]?

The clear majority of female and male students in favour of the use of these expressions can be seen in both figures. However, slight difference can be appreciated in the attitude of the male students and the female students. While the female students were in the majority in accepting profesorado, following what appears to be the general trend, the male students slightly exceeded them in the case of ciudadanía.

In summary, as was found for the case of the use of the @ symbol, the people surveyed showed themselves to be clearly in favour of the use of collective nouns, as demonstrated by the fact that, in the two cases considered, the responses in favour were at least twice the responses against their use.

5.5. Blank Responses

The analysis concludes with the highlighting of two significant pieces of information relating to abstentions. On the one hand, the summary of the low rate of blank responses found in practically all the questions and, on the other hand, the percentages show that the female students appear to vacillate rather more in the majority of cases.

In general, the percentage of blank responses was below 2.5%, which appears to indicate that our students have definite attitudes with respect to these new uses. There are only two cases in which this rate was exceeded, which are striking nonetheless. The first corresponds to question Q7, “Does it seem right to you to use todos y todas [all-masc and all-fem] in political speeches?”. In this case 5.17% of the responses were blank, with a slightly higher percentage of female students undecided than males. The second corresponds to question Q11, “Angela Merkel es[is]...”, which went unanswered in 11.62% of the questionnaires. It is significant that 15.74% of the female students, against 6.07% of the male students, left this question without a response. When Angela Merkel was appointed, laAcademia recommended the masculine title with the feminine article, “la canciller Angela Merkel”, and this has been the only title used in the media since that time. It is curious, then, that vacillation occurs among the students, as if wavering between the non-standardised feminine term and the widespread masculine form (which the Academia has legitimized).

6. Interpretation of the Results

The study carried out attempted to explore and evaluate the attitude of a part of the European Spanish community–university students—towards verbal uses considered non-sexist, in order to check up to what point the feminist reform enjoys acceptance among them.

Once the data relating to the four uses considered have been analysed, it is possible to state that the @ symbol and collective nouns are widely accepted among the student community. This is something which can also be said of the use of dual gender, although greater vacillation was seen and, in some of the cases observed, the levels of rejection or indifference are higher. Nevertheless, of the four uses studied, the one which appears to provoke the greatest hesitation, vacillation or even opposition is the use of the feminine for some names of professions. While some are fully accepted, others (perita [expert-fem], cancillera* [chancellor-fem] and gerenta [manager-fem]), probably for complex and different reasons, incite almost unanimous rejection. It may be surmised that perita [expert-fem] brings to mind sexist naming of women as edible objects (perita en dulce [gorgeous, literally “little pear in syrup”]); cancillera* [chancellor-fem] has not been permitted by la Academia, and the media therefore apply the masculine with the feminine article to Angela Merkel; and for gerenta [managerfem] the regulatory dictionary proposes the use of the masculine. However, this did not prevent the students surveyed from opting in the majority for arquitecta [architect-fem] or ingeniera [engineer-fem], professions for which the dictionary also proposes only examples of use in the masculine, as shown in section 2 above.

Our survey shows the complexity of job-title feminization and its acceptance by the speech community of Spanish. Nissen already noted that the use and acceptance of occupational titles in the feminine by speakers of Spanish vary considerably according to the title in question. ‘Phonetic criteria and analogies to similar words [...] exert constraints on the acceptance of specific expressions’ (2002: p. 270). Something similar was observed for French, where “existing literature on job-title feminization in the French language suggests a complex relationship between social and linguistic factors” (van Compernolle, 2009: p. 38). For instance, reticence to feminine titles in French is due in large part to the lack of women in certain professions, but also to word-final morphology (van Compernolle, 2008).

We do not claim that our findings attain the category of absolute trends in the community. We are aware of the limitations of this study and humbly accept in advance all the criticism aimed at the methodology adopted, as summarised by Baker (2006: p. 224). We also considered that our work should be complemented by broadening the spectrum of the sample and by means of other qualitative investigations (Ricento, 2006: p. 131), such as discourse analysis (Potter & Wetherell, 1987) and interviews (Baker, 2006).

On the other hand, although we asked about the individual use of some non-sexist alternatives, we are aware of the problematic relationship between attitudes and behaviour indicated in the literature (Garret et al., 2003: pp. 7-9), from the pure difficulty of changing linguistic behaviour to laziness in making long-term commitments, by way of the contradictory attitudes which these changes provoke. We also know of the complex relationship between verbal practices and social, political and ideological factors. Based on this we consider that our results, in this aspect, have only a tentative value. However, what our study makes clear is the existence of ideological forces with emotional charge which do not correspond exactly with those predicted by la Academia.

7. Conjecture on the Motivation for the Attitudes of the Students

Our work did not explain the causes for which the young people in the sample had a rather favourable attitude to the anti-sexist elements in Spanish, being inclined, even, to their use in the majority of cases. It is possible, however, to speculate on the motivations for this attitude—the “social factors” van Compernolle spoke about.

As all attempts at linguistic planning and policies have one or more motives behind them, those who decide to change or not change their verbal uses in response to these policies also have their motives for carrying them out. Attitudes are also motivated. In all cases, and following the classification recorded by Ager (2001), this can involve motives of identity, ideology or image, be instrumental or be based on reasons of integration, insecurity or inequality.

It is well known that in the background of feminist linguistic policies lies the conviction that the verbal use contributes to the discrimination to which women are subject and that action on the language will have a correcting effect on gender inequality. To this effect, it is highly significant that in the case of European Spanish, the feminist linguistic policies have arisen accompanied by laws oriented to social equality as regards men and women, basically Ley Orgánica 1/2004, de 28 de diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral contra la Violencia de Género [Organic Law 1/2004, of 28 December, on Measures for Comprehensive Protection against Gender Violence] and Ley Orgánica 3/2007, de 22 de marzo, para la igualdadefectiva de mujeres y hombres [Organic Law 3/2007, of 22 March, for the Effective Equality for Women and Men]. Is this motivation the only one which would explain the attitudes of our students? Probably not.

Paulston (2002) and Spol sky (2006) have argued convincingly about the complex connection between attitudes, motivation and linguistic policies. Due to this complexity, it is difficult in this study to distinguish whether the relatively positive attitude to non-sexist elements of Spanish represents support for the egalitarian social policies of different governments, whether the relative success of the social equality policies applied by the governments has backed up the attitude of university students to non-sexist Spanish, or rather social policies and linguistic policies have supported each other mutually. The motivations underlying the positive attitudes of university students surely lie both in feminist pressure and government intervention, in the realisation of existing social injustice, in the identity associated with the use of anti-sexist forms and in the relative spread of anti-sexist forms, which may have led students to become accustomed to their use unconsciously. Likewise, the broad acceptance and use of the @ symbol may be linked to its belonging to a new computer-literate generation.

In any case, behind a community’s attitudes to a linguistic variety are hidden its beliefs and values. Following Katz (1960), Baker suggests that a certain attitude towards the language is activated when it is coherent with the concept that a person has of herself or himself and with her or his system of values (1992: p. 110). Perhaps we may conclude that the positive attitude of university students, without indicating the complete success of nonsexist linguistic policies, does suggest a degree of success in the spread and acceptance of the verbal elements which make up these policies. It probably shows simultaneously a positive attitude towards the social policies of equality between the sexes which have accompanied it, although this statement is merely a hypothesis which would need new studies to endorse it. In any case, the non-sexist forms in this study already appear to be part of the imaginairel inguistique (Houdebine-Gravaud, 2003) of a large part of the body of students in this sample, especially the females, which would facilitate the expression of their own identity and that of other women.

References

- Ager, D. (1996). Language Policy in Britain and France. London: Cassells.

- Ager, D. (2001). Motivation in Language Planning and Language Policy. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Baker, C. (1992). Attitudes and Language. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Baker, C. (2006). Psycho-Sociological Analysis in Language Policy. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An Introduction to Language Policy. Theory and Method (pp. 210-228). London: Blackwell.

- Bengoechea, M. (2000). Historia (Española) de Unas Sugerencias Para Evitar el Androcentrismo en el Lenguaje. Discurso y Sociedad, 2, 33-58.

- Bengoechea, M. (2008). Lo Femenino en la Lengua: Sociedad, Cambio y Resistencia Normativa. Estado de la Cuestión. Lenguaje y Textos, 27, 37-68.

- Bengoechea, M. (2011). Non-Sexist Spanish Policies: An Attempt Bound to Fail? Current Issues in Language Planning, Special Issue: Language Planning and Feminism, 12, 35-53.

- Calero Fernández, M. A. (2006). Creencias y Actitudes Lingüísticas en Torno al Género Gramatical en Español. In M. I. Sancho Rodríguez, L. Ruiz Solves, & F. Gutiérrez García (Eds.), Estudios Sobre Lengua, Literatura y Mujer (pp. 235-285). Jaén: Universidad de Jaén.

- Council of Europe. (1986). Igualdad de Sexos en el Lenguaje. Comisión de Terminología en el Comité Para la Igualdad Entre Mujeres y Hombres Del Consejo de Europa.

- Edwards, J. (1982). Language Attitudes and Their Implication among English Speakers. In E. Bouchard Ryan, & H. Giles (Eds.), Attitudes towards Language Variation (pp. 20-33). London: Edward Arnold.

- European Parliament. (2008). Informe Sobre el Lenguaje no Sexista en el Parlamento Europeo (Aprobado Por la Decisión Grupo de Alto Nivel Sobre Igualdad de Género y Diversidad de 13 de Febrero de 2008). PE 397.475.

- Druon, M. (1999). Le Bon Français. du Governement. Le Figaro, 7 août.

- Garret, P. (2010). Attitudes to Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511844713

- Garret, P., Coupland, N., & Williams, A. (2003). Investigating Language Attitudes: Social Meanings of Dialect, Ethnicity and Performance. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Guerrero Salazar, S. (2007). Esbozo de Una Bibliografía Crítica Sobre Recomendaciones y Guías Para un Uso Igualitario Del Lenguaje Administrativo. In A. M. Medina Guerra (Ed.), Avanzando Hacia la Igualdad (pp. 109-122). Málaga: Diputación de Málaga & AEHSM.

- Henerson, M., Morris, L., & Fitz-Gibbon, C. (1987). How to Measure Attitudes. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Houdebine-Gravaud, A. M. (2003). Trente ans de Recherche sur la Différence Sexuelle, ou le Langage des Femmes et la Sexuation Dans la Langue, les Discours, les Images. Langage & Société, 106, 33-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.3917/ls.106.0033

- Jaehrling, S. (1988). Attitudes to Sexist and Non-Sexist Language: A Comparative Study of German and Australian Informants. Unpublished B. A. Thesis. Melbourne: Department of German, Monash University.

- Katz, D. (1960). The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitude. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24, 163-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/266945

- Likert, R. (1932). A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lledó Cunill, E., Calero Fernández, M. A., & Forgas Berdet, E. (2004). De Mujeres y Diccionarios. Evolución de lo Femenino en la 22nd Edición del DRAE. Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer.

- Muray, P. (2000). L’homme du XXe siècle sera une femme. Le Monde, 4 janvier.

- Nissen, U. K. (1991). Feminise-Ringstendenser i Modernespansk. Ph.D. Dissertation. Odense: Odense University.

- Nissen, U. K. (1997). Do Sex-Neutral and Sex-Specific Nouns Exist? The Way to Non-Sexist Spanish. In F. Braun, & U. Pasero (Eds.), Kommunikation von Geschelecht. Communication of Gender (pp. 222-241). Pfaffenweiler: Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Nissen, U. K. (2002). Gender in Spanish: Tradition and Innovation. In M. Hellinger, & H. Bussman (Eds.), Gender across Languages: The Linguistic Representation of Women and Men, Vol. 2. (pp. 251-279). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Nissen, U. K. (2013). Is Spanish Becoming More Gender Fair? A Historical Perspective on the Interpretation of GenderSpecific and Gender-Neutral Expressions. Linguistik Online, 58. http://www.linguistik-online.net/58_13/nissen.html

- Oppenheim, B. (1992). An Exercise in Attitude Measurement. In G. Breakwell, H. Foot, & R. Gilmour (Eds.), Social Psychology: A Practical Manual (pp. 38-53). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Paulston, C. B. (2002). Review of Dennis Ager, Motivation in Language Planning and Language Policy, and Kas Deprez and Theo Du Plessis, Multilingualism and Government. Language in Society, 31, 790-796.

- Pauwels, A. (1998). Women Changing Language. London: Longman.

- Potter, J., & Wetherell, M. (1987). Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour. London: Sage.

- Real Academia Española. (1931). Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- Real Academia Española. (1992). Diccionario de la Lengua Española (21st ed.). Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- Real Academia Española. (2001). Diccionario de la Lengua Española (22nd ed.). Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- Real Academia Española. (2006). Informe Emitido por la RAE Relativo al Uso Genérico del Masculino Gramatical y al Desdoblamiento Genérico de Los Sustantivos. Revista Española de la Función Consultiva, 6, 307-308.

- Real Academia Española, & Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Españolas. (2005). Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas. Madrid: Santillana.

- Real Academia Española, & Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Españolas. (2009). Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- Rey-Debove, J. (1998). Madame “la” Ministre. Le Monde, 14 Janvier.

- Ricento, T. (2006). Methodological Perspectives in Language Policy: An Overview. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An Introduction to Language Policy. Theory and Method (pp. 129-134). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Sarnoff, I. (1970). Social Attitudes and the Resolution of Motivational Conflict. In M. Jahoda, & N. Warren (Eds.), Attitudes (pp. 279-284). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Schafroth, E. (1993). Berufsbezeichnungenfür Frauen in Frankreich: Sprachpolitische Massnahmen und Sprachliche Wirklichkeit. Lebende Sprachen, 2, 64-66.

- Spolsky, B. (2006). Language Policy Failures. In M. Pütz, J. Fishman, & J. Neff-van Aertselaer (Eds.), Along the Routes of power. Explorations of Empowerment through Language (pp. 87-106). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110923247.87

- Thomas, G. (1991). Linguistic Purism. London: Longman.

- UNESCO. (1990). Recomendaciones Para un Uso no Sexista de la Lengua. Paris: UNESCO.

- van Compernolle, R. A. (2008). “Une Pompière? C’est Affreux!” Étude Lexicale de la Féminisation des Noms de Métiers et Grades en France. Langage & Société, 123, 107-126.

NOTES

1We thank Instituto de la Mujer’s [Spanish Women’s Institute] (Research grant 37/06) and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación’s (Research grant FEM2009-10976) financial support for carrying out this work. Likewise, we wish to thank Verónica González Araujo for her collaboration in the design and execution of the surveys. We are also grateful to the teachers of both universities who collaborated with us.

2Nissen (1991, 1997, 2013) and Calero Fernández (2006) have carried out a study of cognitive attitudes in sexist and non-sexist language forms, but not a study of affective attitudes towards them.

3Except for some neuter pronouns, the rest of the Greco-Latin gender system.

4The new edition to be published in 2014 may change the matter slightly, as more feminine titles will be accepted as the only standard form.

5An asterisk indicates that the term has not been accepted as standard by la Academia.

6In 2005 a reference work, DiccionarioPanhispánico de Dudas, was published, with agreements on matters of usage. It was authored jointly by the Association of Academies of the Spanish Language (the Spanish itself, and the Latin-American, New York and the Philippines Academies). In its introduction, the Panhispánicopresents itself as normative, with usage recommendations for “most common doubts”. In this reference work, the feminine terms for doctor, architect or engineer (médica, arquitectaor ingeniera) were recommended, and the masculine terms (médico, arquitectoand ingeniero) expressly proscribed to refer to women (Real Academia Española &Asociación de Academias de la LenguaEspañolas, 2005: 63, 363, 428). It has taken several years to the Dictionary to include this recommendation in its Dictionary, but in the forthcoming edition, the 24th (2014), the examples of use referring to women only in the masculine will have disappeared for the three entries. When our survey was carried out though, the examples of use in the masculine were still present.

7Although, on the other hand, this appears to be irrefutable proof of the spread of their use (Bengoechea, 2000, 2008, 2011).

8Obviously, we cannot ensure that the students were responding to the language here rather than the content. Maybe they were saying that they accepted having to go to class 80% of the time but they didn’t agree with it (rather than reacting to the non-sexist language).