Open Journal of Animal Sciences

Vol.05 No.03(2015), Article ID:57813,10 pages

10.4236/ojas.2015.53033

Prediction of Feed Intake and Its Relationships with Chemical Composition of Diets in Goats Consuming Concentrate, Bahiagrass Pasture and Mimosa Browse

B. R. Min*, S. Solaiman

Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, USA

Email: *minb@mytu.tuskegee.edu

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 5 May 2015; accepted 6 July 2015; published 9 July 2015

ABSTRACT

An indoor and a grazing experiment was conducted to determine how estimated feed intake and digestion by grazing goats consuming concentrate, bahaigrass pasture, and mimosa browse changed with body weight (BW), level of supplementation, and forage chemical composition. Twenty four Boer wether goats were assigned in a completely randomized design with repeated measures on the following 3 treatments: concentrate, mimosa browse, and bahiagrass pasture. Internal markers used to estimate both dry matter (DM) digestibility (DMD) and DM intake (DMI) included acid detergent lignin (ADL) and acid insoluble ash (AIA). Marker-derived estimates of DMD and DMI were compared with DMD measured by total fecal collection or directly measured by in vivo feed intake rate. Both ADL and AIA-based markers in mimosa and bahiagrass diets were similar from those derived by in vivo DMD; however, AIA-based marker in concentrate was under-estimated (P < 0.01). These results indicate that ADL and AIA indigestible markers performed similarly to in vivo DMD in mimosa and bahiagrass, although AIA concentration in mimosa seemed to be low compared to others. All markers yielded feed intake estimates that differed from those derived by ADL (P < 0.03), AIA (P < 0.01), and in vitro DMD (P < 0.001) compared to in vivo control, with ADL (P < 0.05) and in vitro DMD (P < 0.01) by period interactions, indicating that estimated intake from ADL and in vitro DMD increased more in mimosa browse diet with time period than in concentrate and bahiagrass diets with that estimated intakes being decreased with corresponding the second period due to lower in vitro DMD (21% to 4%) in second period compared to the first period in both concentrate and bahiagrass diets, respectively. In the present study, mean marker recoveries were higher (P < 0.01) for bahiagrass and mimosa diets than for the concentrate diets for both ADL- and AIA-based markers. It can be concluded that the use of natural markers in ADL and AIA offers advantages over the total fecal collection or direct measurement of in vivo intake methods for digestibility studies. Both ADL and AIA occur in common forages at readily measurable levels and laboratory procedures are not difficult or time consuming. Therefore, both ADL and AIA have possible use in digestibility studies where other methods may not be applicable.

Keywords:

Digestibility, Intake, Markers, Lignin, Ash

1. Introduction

Goats are typically browsing animals; if allowed free access to grazing and browse, they generally obtain 60 to 80% of their diet from browse plants. However, determination of the amount eaten and characteristics of the diet of grazing goats remains one of the most difficult tasks in research. Internal markers have been widely used in site and extent of digestion and for determining dry matter intake (DMI) under grazing conditions, and they include chromium sesquioxide (Cr2O3), rare earth elements such as ytterbium (Yb), and long-chain alkane waxes (C32 and C36) [1] - [3] . Other internal markers that have been evaluated are silica, lignin, fecal N, chromogen, indigestible neutral detergent fiber, and acid insoluble ash [3] . All have problems of consistent recovery. Calibration must occur for each set of conditions, and therefore they have limited application [4] . Lignin is probably the most widely used internal marker, but suffers from variation in digestibility. The most recent development of a marker system has been the use of the hydrocarbons (n-alkanes) of plant wax. By using dosed synthetic alkanes as external markers to estimate fecal output together with naturally occurring plant wax alkanes, diet selection, intake, and digestibility can be determined [1] . Problems with the alkane technique include variable recovery and low concentrations of natural waxes in some plants, especially tropical and subtropical species [5] . Digestibility is probably best estimated by the in vitro technique [6] , but for some tropical forages such as bahiagrass, in vitro dry matter digestibility (DMD) does not predict in vivo digestibility well. Nelson et al. [7] showed that bahiagrass forage required incubation for 72 h to reach typical in vivo digestibility as opposed to 48 h routinely used in in vitro systems. Therefore, potential intake cannot be reliably predicted from estimates of digestibility. An ideal internal marker is currently not available. Moreover, because of the labor involved and the extreme number of laboratory assessments required, the use of markers have received little or no application by producers nor routinely in large experiments from which to develop a database of samples useful for equation development and prediction of diet quality from chemical or other characteristics of harvested forage.

Extensive research has been conducted over the years on concentrate supplementation level at pasture for ruminants [8] - [10] . However, accurate estimate of feed intake rate for grazing and browsing goats were not well established. Inconsistent results frequently have been reported when a given marker is applied over the various forages or in different laboratory methods [11] [12] . Cochran et al. [12] and Judkins et al. [13] fed alfalfa forage and observed underestimation of DM digestibility by acid detergent lignin (ADL) compared with total fecal collection. Consistent with the positive recovery of acid insoluble ash (AIA), organic matter digestibility (OMD) was greatly overestimated [14] . Thonney et al. [15] suggested that diets containing less than 0.75% AIA may produce subjective estimates of digestibility. In contrast, Keulen and Young [16] reported that DMD estimates from AIA were not different from those measured by total fecal collection. Warm-season grasses and browse legumes such as bahiagrass pasture and mimosa browse are commonly consumed by the goats in the southern United States in grazing condition. Therefore, certain validated particular internal markers are needed to be evaluated based on their ability to accurately predict DMD and DMI across different forage types before application in a research setting. The present study was conducted to determine how estimated feed intake and digestion by grazing goats consuming concentrate, bahiagrass pasture, and mimosa browse changed with body weight (BW), level of supplementation, and forage chemical composition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

Twenty four 8 month old Boer wether goats (n = 8) were assigned in a completely randomized design with repeated measures on the following 3 treatments: concentrate, mimosa browse, and bahiagrass pasture to evaluate the efficacy of different internal markers for estimating DMD and DMI. Internal markers used to estimate both DMD and DMI included ADL and AIA. Marker-derived estimates of DMD and DMI were compared with DMD measured by total fecal collection or directly measured by in vivo feed intake rate.

2.2. Animals and Diets

Fresh vegetative bahiagrass forage and mimosa browse were grazed by the goats except for concentrate treatment group (confined and fed bermudagrass hay). Animals were confined indoors for a period of 14 days and fed 40:60 soyhull pellet: bermudagrass hay diet on a DM basis. Animals were weighed for two consecutive days, stratified by BW and randomly assigned within Boer breed to one of three production systems: 1) concentrate grain diet containing 40% protein pellets, 40% soybean hulls, and 20% bermudagrass hay; 2) ad libitum consumption of bahiagrass pasture supplemented with 150 g/head/day protein pellets; 3) ad libitum consumption of mimosa browse supplemented with 100 g/head/day of cracked corn. Animals fed the concentrate diet were housed individually in 1.8 m × 2.1 m pens with raised mesh floors. Fresh water and feed were supplied daily. Animals assigned the bahiagrass diet were grazed on 0.8 hectare pasture containing bahiagrass and fed protein pellet once daily. The mimosa browse animals were rotated every two weeks between four mimosa plots (0.4 hectare) with trees trimmed to a height of 1.2 m and fed cracked corn once daily. Body weights were recorded after a four hour withdrawal from feed and water, for two consecutive days every two weeks. The growth period consisted of 14 weeks.

A 0.4 hectare paddock of 6-year-old mimosa was used in this study. Mimosa plants had been planted in rows 1.8 m apart, with about 0.45 m between plants within rows. However, annual mowing in late winter had caused considerable thinning of the stand. The paddock was mown in April, and growth was allowed to accumulate without defoliation for the entire summer. By the end of September, mimosa plants had mostly 5 to 8 stems that ranged between 1.8 and 3 m in length. The Tuskegee University Animal Use Committees approved the animal care, handling, and sampling procedures.

2.3. Intake and Digestibility

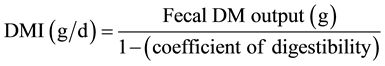

Actual (in vivo) and estimated feed intake and digestibility were measured on eight goats from each treatment group for 10 days. Estimated dry matter (DM) intake (DMI) was calculated as follows using in vitro DM digestibility (DMD) from forage samples [2] .

Total fecal output was measured using fecal bags. Internal markers used to estimate both DMD and DMI included ADL and AIA. Marker-derived estimates of DMD and DMI were compared with DMD measured by total fecal collection or directly measured by in vivo feed intake rate.

Goats were fitted with canvas fecal collection bags and allowed three days to adapt to the bags before initiation of a five day fecal collection period. Fecal collection bags were emptied twice daily. Daily collected feces were weighed, mixed, and a constant percentage (2%) for each animal was taken to be dried at 55oC; this was followed by a 24 hour air equilibration to determine air dried fecal output. Daily fecal samples were pooled relative to the 24 hour air dried fecal output to provide a representative sample of the five day collection period. During the five day collection period, samples of pasture, browse, hay and supplements were taken daily, composited, and subsampled. Samples were ground through a 1-mm screen in a Wiley Mill (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ, USA) prior to laboratory analyses.

2.4. Chemical Analysis

Pasture, browse, hay and supplement samples were collected weekly during the entire trial, ground through a 1-mm screen in a Wiley Mill and pooled by month for chemical analysis of DM, crude protein (CP), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), cellulose, ADL and AIA.

Feed samples and fecal samples from the fecal collection period were analyzed for DM and nitrogen determined by the combustion method [17] utilizing the Leco FP-2000 (Leco Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA). Crude protein was calculated as N × 6.25. Neutral detergent fiber, ADF, cellulose and ADL were analyzed as described by Van Soest et al. [18] modified [19] for use in an Ankom fiber apparatus (Ankom Technology, Macedon, NY, USA). Acid insoluble ash determination followed the procedure of Keulen and Young [16] utilizing a 2N HCl acid solution.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Twenty four Boer wether goats were assigned in a completely randomized design with repeated measures on the following 3 treatments: concentrate, mimosa browse, and bahiagrass pasture .The model included the fixed effects of treatment, sampling week (week 1 and week 2), and treatment × week interaction.

For variables measured repeatedly over the experiment, such as forage chemical composition, digestibility, fecal output and feed intake data, the GLM procedures of SAS was used to asses DMI, DMD, and their interaction [20] . Means were separated using least-square means. Differences were declared significant at P < 0.05 unless otherwise indicated. The correlation coefficient relationships among fecal output, BW and DMI for goats fed concentrate, mimosa browse and bahiagrass pasture were analyzed by regression analysis on each treatment.

3. Results and Discussion

Chemical composition of feeds and in vitro organic matter digestibility are listed in Table 1. Average composi-

Table 1. Chemical composition (% DM) and in vitro OM digestibility (IVOMD) of pasture and concentrate fed by goats.

*IVOMD, in vitro organic matter digestibility (72 h incubation). 1Treatments A (concentrate), B (bahiagrass pasture), and C (mimosa browse) were supplemented with 800 (treatment A) and 150 (Treatments B and C) g of concentrate. Fresh vegetative bahiagrass forage and mimosa browse were grazed by the goats except for treatment A (confined and fed Bermuda grass hay). ADL = acid detergent lignin; AIA = acid insoluble ash. a,b,cMeans within a treatment or mean grouping without a common superscript letter differ (P < 0.05).

tion of CP, ADF, lignin and ADL were higher (P < 0.001) for mimosa browse than for other diets, but cellulose content and in vitro organic matter (OM) digestibility (IVOMD) were higher (P < 0.01) for concentrate among diets. Average OM, NDF and AIA contents were higher (P < 0.01) for bahiagrass than for other diets.

Estimates of concentrate, bahiagrass and mimosa browse DMD by ADL and AIA-based internal markers were differed among diets (P < 0.001; Table 2). An average DMD estimated from ADL and AIA markers in bahiagrass was the highest (P < 0.001) among diets, with ADL by sampling time (P < 0.001) interactions, indicating that estimated DMD from ADL decreased more in concentrate and bahiagrass diets with time than in mimosa diets with that estimated DMD being decreased with corresponding the second sampling time compared to the first week.

Both ADL and AIA-based markers in mimosa and bahiagrass diets were similar from those derived by in vivo DMD; however, DMD estimated from AIA-based marker in concentrate was about 8% under-estimated (P < 0.01). These results indicate that ADL and AIA indigestible markers performed similarly to in vivo DMD in mimosa and bahiagrass in estimating forage DMD, but not in the concentrate, although AIA concentration in mimosa seemed to be low compared to others as recommended by Thonney et al. [15] . Thonney et al. [15] suggested that diets containing less than 0.75% AIA may produce under estimates of digestibility; average concentration of AIA for the diets used in the present study was similar or greater than 0.75% except mimosa diet (0.3%). Although concentration of AIA was low in mimosa browse, there was no significant difference between DMD coefficients (%) determined by the marker methods and by the in vivo DMD method in this study. Van Soest [21] has recommended that optimal concentration of ADL as an internal marker was at least 6% of the DM. In our study, ADL concentration in the diets seems to be similar to this concentration except bahiagrass (2.8%).

Initial BW (28.5 ± 1.6 kg; data not shown in the text) was similar among diets, but final BW was higher for concentrate (39.6 kg; P < 0.01) than for bahiagrass (32.3 kg) and mimosa browse (36.9 kg) diets. Mean fecal

Table 2. Mean dry matter digestibility (DMD) of concentrate, mimosa and bahiagrass estimated by the in vivo DMD, acid detergent lignin (ADL) and acid insoluble ash (AIA) natural markers with total fecal collection.

ADL = acid detergent lignin; AIA = acid insoluble ash.

DM outputs were similar (data not shown in text) among concentrate (273.7 g DM), Bahiagras (269.4 g DM) and mimosa browse (273.5 g DM) diets.

All markers yielded feed intake estimates that differed from those derived by ADL (P < 0.03), AIA (P < 0.01) and IVDMD (P < 0.001) compared to in vivo control, with ADL (P < 0.05) and in vitro DMD (P < 0.01) by period interactions (Table 3), but there were ADL (P < 0.05) and in vitro DMD (P < 0.01) by sampling time interactions, indicating that estimated intake from ADL and in vitro DMD increased more in mimosa browse diet with time than in concentrate and bahiagrass diets. Estimated MDI was decreased with corresponding the second sampling time due to lower in vitro DMD (21 to 4%) compared to the first sampling time in both concentrate and bahiagrass diets.

Sunvold and Cochran [10] reported that all markers recoveries (ADL and AIA) were less than 100% in alfalfa hay except brome and prairie hays, for which recovery was considerably greater than 100%. Mean marker recoveries (Table 4) were less than 100% in our study. Consistent with the positive recovery of ADL and AIA in this study, intake was successfully estimated. Although the AIA procedure accurately predicted DMD and feed intake for the forage diets, there should be caution when it applied to grazing conditions because of the potential soil contamination [11] . In the present study, mean marker recoveries were higher (P < 0.01) for bahiagrass and mimosa diets than for the concentrate diets for both ADL- and AIA-based markers, with diet and time interac-

Table 3. Dry matter feed intake (DMI) estimated by different techniques in goats fed concentrate, pasture and mimosa browse.

1Treatments groups in concentrate, bahiagrass pasture, and mimosa browse were supplemented with 800 (concentrate) and 150 g (bahiagrass and mimosa) of concentrate. Fresh vegetative bahiagrass forage and mimosa browse were grazed by the goats except for concentrate treatment (confined and fed Bermuda grass hay). ADL = acid detergent lignin; AIA = acid insoluble ash. a,b,cMeans within a treatment or mean grouping without a common superscript letter differ (P < 0.05).

Table 4. Fecal recovery of internal markers in concentrate, bahiagrass and mimosa browse diets.

ADL = acid detergent lignin; AIA = acid insoluble ash.

tions for ADL, indicating that marker recoveries from ADL in concentrate and bahiagrass diets decreased with time.

To further understand the effect of fecal output, they were regressed against estimated DMI for goats fed concentrate, bahiagrass and mimosa browse diets (Figure 1). Intake estimated from ADL, AIA and in vitro DMD related to fecal DM output had positive effect for mimosa browse (Figure 1(b); R2 = 0.73 to 0.99; P < 0.001) and bahiagrass (Figure 1(c); R2 = 0.79 to 0.98; P < 0.001). However, DMI estimated from concentrate diet was not linearly related with fecal DM output. As fecal DM output increased, DMI estimated from mimosa and bahiagrass increased linearly, but total DMI estimated in concentrate diet had was variable.

As BW increased, total DMI increased linearly for mimosa browse (Figure 2(b); R2 = 0.44 to 0.73; P < 0.01). Estimated DMI in low quality bahiagrass diet, however, did not correlated (R2 = 0.075; P < 0.306) with BW (Figure 2(b)). Goetsch et al. [9] reported that as BW increased, total DMI (kg) increased quadratically in Holstein steer. Likewise, the kilograms of Bermudagrass DM consumed increased quadratically with increasing BW. Consumption of high concentrate (Figure 2(a)) diet by goats in this study had negatively effects for DMI against BW, indicating that goats are sensitive to diets to high concentrate diets. The rumen pH decreases when the concentrate proportion in diets exceeds 60% DM [22] . If the lowering of rumen pH, symptom of acidosis can appears as diarrhea and a fall intake. Therefore, the next step in predicting intake is to model it by taking into account the characteristics of goats feeding behavior.

4. Conclusion

It can be concluded that the use of natural markers in ADL and AIA offers some apparent advantages over the

Figure 1. Relationship between fecal output of dry matter (DM; kg/d) and dry matter intake (DMI) for goats fed concentrate (a); mimosa browse (b) and bahiagrass pasture (c); Treatments a, b, and c were supplemented with 800 (treatment a) and 150 (treatments b and c) g of concentrate. Fresh vegetative bahiagrass forage and mimosa browse were grazed by the goats except for treatment a (confined and fed Bermuda grass hay). ADL = acid detergent lignin; AIA = acid insoluble ash.

Figure 2. Relationship between body weight (BW; kg) and dry matter intake (DMI) for goats fed concentrate (a), mimosa browse (b) and bahiagrass pasture (c). Treatments a, b, and c were supplemented with 800 (treatment a) and 150 (treatments b and c) g of concentrate. Fresh vegetative bahiagrass forage and mimosa browse were grazed by the goats except for treatment a (confined and fed Bermuda grass hay). ADL = acid detergent lignin; AIA = acid insoluble ash.

total fecal collection method for digestibility studies. Both ADL and AIA occur in common forages at readily measurable levels and laboratory procedures are not difficult or time consuming. Therefore, both ADL and AIA have possible use in digestibility studies where other methods may not be applicable.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program, which is funded by the US Department of Agriculture-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA), the USDA/NIFA Evans-Allen Research Program and Tuskegee University, George Washington Carver Agricultural Research Station.

References

- Dove, H. (1996) The Ruminant, the Rumen and the Pasture Resource: Nutrient Interactions in the Grazing Animal. In: Hodgson, J. and Illius, A.W., Eds., The Ecology and Management of Grazing Systems, CAB Intl., Wallingford, 219- 246.

- Min, B.R., McNabb, W.C., Barry, T.N., Kemp, P.D., Waghorn, G.C. and McDonald, M.F. (1999) The Effect of Condensed Tannins on Reproductive Efficiency and Wool Production in Sheep Grazing Lotus corniculatus. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 132, 323-334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0021859699006371

- Burns, J.C., Pond, K.R. and Fisher, D.S. (1994) Measurement of Forage Intake. In: Fahey Jr., G.C., et al., Eds., Forage Quality, Evaluation, and Utilization, ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, Madison, 494-526.

- Weir, W.C., Meyer, J.H. and Lofgreen, G.P. (1959) Symposium on Forage Evaluation: VI: The Use of the Esophageal Fistula, Lignin, and Chromogen Techniques for Studying Selective Grazing and Digestibility of Range and Pasture by Sheep and Cattle. Agronomy Journal, 51, 235-237. http://dx.doi.org/10.2134/agronj1959.00021962005100040014x

- Loredo, M.A., Simpson, G.D., Minson, D.J. and Orpin, C.G. (1991) The Potential for Using n-Alkanes in Tropical Forages as a Marker for the Determination of Dry Matter Intake by Grazing Ruminants. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 117, 355-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0021859600067101

- Tilley, J.M.A. and Terry, R.A. (1963) A Two-Stage Technique for the in Vitro Digestion of Forage Crops. Grass and Forage Science, 18, 104-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2494.1963.tb00335.x

- Nelson, B.D., Montgomery, C.R., Schilling, P.E. and Mason, L. (1975) Effects of Fermentation Time on in Vivo/in Vitro Relationships. Journal of Dairy Science, 59, 270-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(76)84194-X

- Egan, J.K. and Doyle, P.T. (1982) The Effect of Stage of Maturity in Sheep upon Intake and Digestion of Roughage dIets. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 33, 1099-1121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/AR9821099

- Goetsch, A.L., Johnson, Z.B., Galloway Sr., D.L., Foster Jr., L.A., Brake, A.C., Sun, W., Landis, K.M., Lagasses, M.L., Hall, K.L. and Jones, A.L. (1991) Relationships of Body Weight, Forage Composition, and Corn Supplementation to Feed Intake and Digestion by Holstein Steer Calves Consuming Bermudagrass Hay ad Libitum. Journal of Animal Science, 69, 2634-2645.

- Sunvold, G.D. and Cochran, R.C. (1991) Evaluation of Acid Detergent Lignin, Alkaline Peroxide Lignin, Acid Insoluble Ash, and Indigestible Acid Detergent Fiber as Internal Markers for Prediction of Alfalfa, Bromegrass, and Prairie Hay Digestibility by Beef Steers. Journal of Animal Science, 69, 4951-4955.

- Galyean, M.L., Krysl, L.J. and Rstell, R.E. (1986) Marker Based Approaches for Estimation of Fecal Output and Digestibility in Ruminants. In: Owbens, F.N., Ed., Feed Intake by Beef Cattle: Symposium, Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station MP-121, Stillwater, 96-113.

- Cochran, R.C., Vanzant, E.S., Jacques, K.A., Galyean, M.L., Adams, D.C. and Wallace, J.D. (1987) Internal Markers. Proceedings of the Grazing Livestock Nutrition Conference, Laramie, 23-24 July 1987, 39-48.

- Judkins, M.B., Krysl, L.J. and Barton, R.K. (1990) Estimating Diet Digestibility: A Comparison of 11 Techniques across Six Different Diets Fed to Rams. Journal of Animal Science, 68, 1405-1411.

- Penning, P.D. and Johnson, R.H. (1983) The Use of Internal Markers to Estimate Herbage Digestibility and Intake. 1. Potentially Indigestible Cellulose and Acid Insoluble Ash. Journal of Agricultural Science, 100, 127-135.

- Thonney, J.M., Palhof, B.A., De Carlo, M.R., Ross, D.A., Firth, N.L., Quaas, R.L., Perosio, D.J., Duhaime, D.J., Rollins, S.R. and Nour, A.Y.M. (1985) Sources of Variation of Dry Matter Digestibility Measured by the Acid Insoluble Ash Marker. Journal of Dairy Science, 68, 661-671. http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(85)80872-9

- Van keulen, J. and Young, B.A. (1977) Evaluation of Acid Insoluble Ash as a Natural Marker in Ruminant Digestibility Studies. Journal of Animal Science, 44, 282-290.

- AOAC (1984) Official Methods of Analysis. 14th Edition, Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Arlington, VA.

- Van Soest, P.J., Robertson, J.B. and Lewis, B.A. (1991) Methods for Dietary Fibre, Neutral Detergent Fibre and Non-Starch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. Journal of Dairy Science, 74, 3583-3597. http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2

- Kumar, U., Sareen, V.K. and Singh, S. (1994) Effect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Yeast Culture Supplement on Ruminal Metabolism in Buffalo Calves Given a High Concentrate Diet. Animal Production, 59, 209-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003356100007698

- SAS (1990) SAS User’s Guide: Statistics. Version 5 Edition, SAS Institute Inc., Cary.

- Van Soest, P.J. (1987) Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant. Cornell University Press, New York, 39-57.

- Goncalves, A.L., Lana, R.P., Rodrigues, M.T., Viera, R.A.M., Queiroz, A.C. and Henrique, D.S. (2001) Nicternal Pattern of Ruminal pH and Feeding Behaviour of Dairy Goats Fed Diets with Different Roughage to Concentrate Ratio. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 30, 1886-1892.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.