Creative Education 2011. Vol.2, No.4, 370-374 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/ce.2011.24052 Outcome Measures of a Family-Based Education Approach with Mexican Immigrants in the Yakima Valley Virginia A. Bennett, Carissa Sundsmo-Switzer Department of Nutrition, Exercise & Health Sciences, Central Washington University, Washington, USA. Email: bennettv@cwu.edu Received July 26th, 2011; revised August 30th, 2011; accepted September 8th, 2011. With the continued incidence of obesity and health related issues in the United States and especially in the His- panic population, it is important to provide useful healthy lifestyle education to this population. One of the bar- riers to providing this information is the lack of culture sensitivity in the content and presentation of current pro- grams. In this pilot study, pre and post tests were used to measure the effectiveness of Salsa, Sabor, y Salud, a culturally sensitive program designed for Latinos. Outcome measures included dietary changes, weight, body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure, heart rate, reported physical activity, and healthy lifestyle score. Diet was evaluated by 24-hour diet recall for both adults and children. Difference in outcome measures was assessed using a dependent t test. Significant decreases in weight, waist circumference, diastolic blood pressure, kilocalories, and grams of carbohydrates were observed. Adults reported an increase in total minutes of physical activity and the importance of living a healthy lifestyle. This culturally sensitive education program, Salsa, Sabor, y Salud, has a positive effect on health related outcome measures. Keywords: Cultural Sensitivity, Mexican Immigrants, Salsa Sabor y Salud Introduction With the continued increase of overweight and obesity in the United States and especially in the Hispanic population (Ogden, Carrol, Curtin, McDowell, Tabak, & Flegal, 2006; Flegal, Ogden, & Carroll, 2004), it is important to provide useful healthy life- style education. One of the barriers to providing this informa- tion is the lack of culture sensitivity in the content and presen- tation of current programs. The Salsa, Sabor, y Salud program has broken the barrier and offers a culturally sensitive program to the Hispanic population on healthy lifestyle choices. How- ever, at this time the only evaluation of the program that has been completed is a participant self assessment and satisfaction sur vey . Although knowledge is an important component to ma k- ing healthy lifestyle changes, it does not always result in par- ticipant compliance. More objective data are necessary to measure the outcomes of an educational program. The purpose of this pilot study was to gather and analysis objective data. Implications of Ethnicity According to the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 36.3% of all adults are overweight and 27.60% are obese in the United States (CDC, 2010). When ethnicity is fac- tored in, a disproportionate number are either Hispanic or non-Hispanic blacks. In 2007, Wang and Beydoun reported a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in the adult His- panic population when compared to the adult non-Hispanic white population, 63.6% and 54.8% respectively. (Wang & Beydoun, 2007). The higher percent of Hispanics with un- healthy weight is further complicated by the increased number of Hispanics without health insurance (Doty, 2003). Even with the extensive research and knowledge of the nutritional and physical activity issues necessary to maintain a healthy life style, there continues to be the challenge of providing effective health education and incorporating it into culturally sensitive programs. Several successful culturally sensitive education programs that target Hispanic minorities focus on diabetes (Mauldon, Melkus, & Cagganello, 2006; Brown, Kouzehananie, Garcia, & Hanis, 2002; Gilmer, Philis-Tsimikas, & Walker, 2005). However, with the rise of obesity and related diseases in our nation, health care has increased its focus on preventive medicine. Kraft in partnership with the National Latino Chil- dren’s Institute has developed Salsa, Sabor y Salud (SSS), a healthy lifestyle program that incorporates Latino traditions to educate families with children under the age of 12 (Barrera, et al., 2002). Two evaluation studies have been conducted to measure participants’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors re- garding a healthy lifestyle. Both of these evaluations had posi- tive results ( Center for Prevention Research and Development, 2005; Huang, et al., 2008). To date, however there have been no studies that have measured objective outcomes of this pro- gram. Program Design The SSS program was created through the collaboration of the National Latino Children’s Institute and Kraft Foods. The program was designed to teach healthy lifestyle choices utiliz- ing the traditions of Latino family gatherings. The curriculum provides 12 hours of instructional and activity time that can easily be adjusted to meet the needs of the organization or group providing the classes. Each session has a theme that educates families on a component of nutrition and physical activity. Themes include: 1) family reunions; 2) ideal pair (beans and rice); 3) mid-day breaks and snacks; 4) seeds from the Americas; 5) the harvest; 6) salsa y sabor; 7) at the park and, 8) the celebration. All classes include both healthy eating edu- cation and a physical activity component. During each session the educational component of the class is broken into three age groups; adults, 8 - 12 year olds and 3 - 7 year olds. The theme being addressed is the same for each group, but provided at the  V. A. BENNETT ET AL. 371 appropriate learning level for each age group. Following the educational component, families come together in one room to share information and participate in a physical activity or ‘play time’. All materials for the program are provided in both Eng- lish and Spanish to meet the needs of the particular group being instructed. There is also an emphasis on ethnic pride and heri- tage that is woven through-out the sessions. Developers of the SSS program speculate that this program design is better suited for a family-based culture. Methodol ogi cal Design/Data An al ysis of Partici pants Study Population Participants were previously enrolled with La Casa Hogar, a local community organization dedicated to providing re- sources to Mexican immigrant women and children, in Ya- kima, Washington. This population served as a sample of convenience for this pilot study. During quarterly registra- tion for classes at La Casa Hogar, participants were pro- vided flyers with information about SSS. Those who were interested in taking the class were enrolled. Sixteen adult female participants enrolled for the spring quarter class and seven adult female participants enrolled in the summer quarter class. Of these, twelve were included in the study. Participants who had missing data or dropped out of the class were not included in the study. For this study, only adult data were used. Children partici- pated in the classes but data are not included in this paper. Study Design The Central Washington University Institutional Research Board approved the study protocol and all participants were provided written informed consent. All explanations and materials were provided in both Spanish and English. If an individual refused to take part in the study, they were still allowed to participate in the SSS progra m. Classes were taught in Spanish by bilingual and bicultural faculty of La Casa Hogar who were trained to teach the class from one of the principal researchers who attended a national training conference for the SSS program. At every class, two Registered Dietitians and two bilingual under- graduate Nutrition and Dietetic students from Central Washington University were in attendance to answer any questions that were related to nutrition and activity and were outside of the scope of the instructor. Subjects acted as their own control with pre and post measurements taken for each participant. All data were collected prior to the first class and one week following the last class. Outcome Measures Pre and post testing was used to assess changes in nutrition and physical activity as a result of the SSS program using the following tools. Anthropometric. Height was recorded to the nearest quarter of an inch. Weight was measured using a balance scale (Conti- nental Scale Corp Health o Meter Model Number 400 G2L). Waist circumference was measured using a Dean flexible non- stretch retractable measuring tape. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kg/ height in m2. Blood Pressure. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure was mea su re d with an automatic digital blood p ressure monitor (O m- ron Model: HEM-725C). Instructions provided by the manufac- ture of the blood pressure monitor were followed. Nutritional Assessment. Diet was assessed using 24-hour dietary recall recorded by trained bi-lingual Nutrition and Die- tetic University students. Three dimensional food models were used to demonstrate and determine serving sizes. Information of all foods and beverages consumed during the 24 hours pro- ceeding the day of the interview from midnight to midnight were recorded. Nutrient Estimation. Mean values for macronutrients and servings from each food group were assessed using Food Proc- essor for Windows (Version 7.9, 2002, ESHA Research, Salem, OR). Percent kilocalories from the macronutrients were calcu- lated. Healthy Lifestyle Knowledge. A pre-and post-test derived from the National Latino Children’s Institute was used to assess knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes of nutrition and physical ac- tivity (Barrera, et al., 2002). All questions were answered using a 5-point Likert scale; 1 meaning strongly disagree through 5 meaning strongly agree. All participants that were included in the sample had to com- plete both the pre measurements and post measurements. Statistical Analysis Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Mean weight, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, resting heart rate, macronutrients, percent kilocalories from macronutrients, and servings of each food group were compared with dependent t test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Results Anthropometric Data. Table 1 shows the mean pre and post anthropometric measures. Mean weight decreased by 1.27 kg (P = 0.005) and mean waist circumference decreased by 3.23 cm (P = 0.004). A decreasing trend in BMI was also observed (P = 0.053). One participant’s waist circumference was not included in the analysis because of missing data. Physical Activity, Blood Pressure, and Heart Rate. Diastolic Table 1. Baseline and post-intervention anthropometric measures. Variable n Baseline Post-intervention P value Weight (kg) 12 72.81 ± 4.04 71.72 ± 4.04 .005* Body mass indexª 12 30.25 ± 1.49 29.75 ± 1.48 .053 Waist circumference (cm) 11 91.49 ± 3.63 88.26 ± 3.45 .004* Systolic blood pressure 12 115.33 ± 4.63 100.08 ± 9.62 .110 Diastolic blood pressure 12 72.25 ± 3.12 65.58 ± 2.74 .008* aCalculated as kg/m2; *P < 0.05.  V. A. BENNETT ET AL. 372 blood pressure decreased significantly (P = 0.008). Positive but insignificant changes were also observed in a decrease in sys- tolic blood pressure. Although participants increased the num- ber of minutes spent doing physical activity by 43 minutes per week, the increase was not found to be significant, nor were there any changes in resting heart rate. Macronutrients. Kilocalories and grams of carbohydrates consumed were significantly lower after SSS (P = 0.012, and 0.019, respectively). There was a decreasing trend in the con- sumption of grams of fat and saturate d fat (P = 0.053 and 0.060, respectively). Servings per Food Group. There was a significant decrease in the number of servings consumed from grains and milk (P = 0.035 and 0.045, respectively). The mean servings of fruits and vegetables consumed increased while consumption of fats and sugars decreased. However, these changes were not significant. Servings per Food Group. There was a significant decrease in the number of servings consumed from grains. Healthy Lifestyle Knowledge. Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants reported an increase in making it a point to eat more healthy foods (P = 0.026). Participants’ belief that eating and physical activity habits have a huge impact on the health of their body also increased, with 100% of participants rating this statement as a 5 on the post test Likert scale (P = 0.039). Implications of the Study For a group of minorities with a high prevalence rate of dia- betes and a high rate of being uninsured, it is especially impor- tant to provide culturally sensitive lifestyle education as a means of prevention. Approximately 40% of Hispanics are uninsured, compared to 25% of African Americans and 14% of non-Hispanic whites (Doty, 2003). Hispanics have a lifetime risk of 45.4% for males and 52.5% for females of developing diabetes (Venkat Narayan, Boyle, Thompson, Sorensen, & Wiliamson, 2003). Hispanics are also less likely to seek medi- cal care or follow medical instructions due to not fully under- standing their doctors (Doty, 2003). This communication bar- rier may be due to Spanish-English translation, understanding written information, or cultural barriers between patients and medical staff (Doty, 2003). For this reason, culturally sensitive education programs are extremely important in this minority group. Other culturally sensitive education programs that target Hispanic populations have focused on improving diabetes con- trol and have been successful in decreasing fasting blood glu- cose, hemoglobin A1C, and cholesterol levels (Mauldon, Melkus, & Cagganello, 2006; Brown, Kouzehananie, Garcia, & Hanis, 2002; Gilmer, Philis-Tsimikas, & Walker, 2005). This study evaluated SSS, a culturally sensitive education program designed to prevent adverse health outcomes, using both objec- tive and subjective tools. The rate of obese adult participants in this study exceeded the rates for Hispanics from the 2008 Behavioral Risk Factor Sur- veillance System in Washington State (CDC, 2010). Fifty per- cent of adult participants were obese and 33% were overweight at the beginning of the class. Adult participants’ mean BMI decreased from obese to overweight status. A BMI greater than 30 is one measure of obesity which is related to many adverse health conditions including gallbladder disease, high blood pre- ssure, high cholesterol, asthma, arthritis and diabetes (Mokad, et al., 2003; Must, Spadano, Coakley, Field, Colditz, & Dietz, 1999). Although not within the recommended BMI of 19.9 - 24.9, the participants decrease in BMI indicates improvement in the weight status. BMI alone is not always an indicator of health risks if an in- dividual has a higher percent of lean body mass. However, when a BMI exceeds 30 and a waist circumference exceeds 40 inches for males and 35 inches for females, there is a strong correlation of high percent of body fat. Abdominal fat is an indicator of central obesity and is associated with mortality related to excess body fat (Biggard, et al., 2005). In the current study, 45% of subjects had a waist circumference greater than 35 inches, decreasing to only 36% after SSS. These results coupled with the significant decrease in weight are particularly impressive as the program’s intention was not weight loss but to focus on a healthy lifestyle. Blood pressure and heart rate were within normal limits prior to the study and therefore little change was expected. Although blood pressure and heart rate did decrease after the program, only diastolic blood pressure was significantly lower. SSS en- courages physical activity by involving the entire family with physical activities such as walking, playing with a parachute, making an obstacle course, etc. Although these activities in- volve getting up and moving, they may not be as high of an intensity as running or riding a bike and therefore may not re- sult in as drastic a change in blood pressure and heart rate as other more intense physical activities. The Latina participants in a prior study stated that it would be easier for them to increase their physical activity if a facility provided child care for them and if there was a class for them to gain more knowledge regarding physical activity (Wilbur, Chandler, Dancy, & Lee, 2003). SSS provided education re- garding physical activity to participants and child care was provided during this time. The fact that the physical activities used in this program were able to be completed while indoors or outdoors at La Casa Hogar, demonstrated that a gym is not needed in order to be physically active. It also allowed for women to learn and apply physical activities that involved their children and could be used as exercise for themselves. When compared to Caucasian populations, Mexican American women have higher levels of physical inactivity (Crespo, Smit, Ander- son, Carter-Pokras, & Ainsworth, 2000; Crespo, Keteyian, Heath, & Sempos, 1996; Slatttery, et al., 2006). However, only 20% of Mexican American women meet the recommend 30 minutes of exercise 3 or more times per week (Mier, Ory, Dongling, Wang, & Furdine, 2007). Participants in the current study averaged 26 minutes 3 times per a week prior to the in- tervention. Average minutes spent doing physical activity in- creased to 35 minutes 3.75 days a week, which meets recom- mendations for weekly physical activity. Studies of diets among Hispanic populations have shown that average caloric intake varies between 1600 and 2400 kilo- calories (Bermudez, Falcon, & Tucker, 2000; Loria, et al., 1995; Guendelman & Abrams, 1995; CDC, 2010). The participants in this study had lower total caloric consumption when compared to other studies. Average caloric intake decreased over the course of the program as well as total grams from all macronu- trients. Percentage of kilocalories from carbohydrates and protein increased. Percentage kilocalories from saturated fat decreased, to less than 7% of kilocalories, which meets the recommenda- tions of the American Heart Association (AHA) (Guendelman & Abrams, 1995). The women in this study were first genera- tion immigrants. Studies of acculturation effect on dietary con- sumption have shown that less acculturated minorities have healthier eating habits than more acculturated (Guendelman & Abrams, 1995; Neuhouser, Thompson, Coronado, & Solomon,  V. A. BENNETT ET AL. 373 2004). Previous studies on Mexican American women born in Mexico found a lower percentage of kilocalories from fat and saturated fat when compared to U.S. born Mexican Americans, but still exceeded the AHA recommendations (Dixon, Sund- quist, & Winkleby, 2000; Loria, et al., 1995; Lichtenstein, et al., 2006). It is important to maintain or improve dietary habits of first generati on immigrants before di ets become westernize d. In this study improvement of dietary habits was accomplished with the use of a culturally sensitive education pr ogra m. When servings of food groups were examined, a decrease in both dairy products and grains was observed. Upon review of the diet recalls, it was noted that the number of corn tortillas consumed decreased as well as the serving size of milk. The SSS class emphasizes portion control and balance in meals using a plate model. Although the plate model used in the class encourages milk to be consumed with meals, the participants in this study elected to decrease their serving size. This was un- expected and will be addressed in future education sessions provided by these researchers. Corn tortillas are a popular source of calcium among Hispanic groups (Block, Norris, Mandel, & DiSogra, 1995). Although the decreased consump- tion of corn tortillas is a positive result for portion control at meals, corn tortillas and milk are among the top five sources of calcium for Hispanics (Block, Norris, Mandel, & DiSogra, 1995). If Hispanics are to decrease the number of corn tortillas they consume daily, it is important that they replace the lost source of calcium with another source to ensure the recom- mended daily allowance of calci um is met. A positive result in the increase of fruits and vegetables was observed. Total fruit and vegetable consumption met the rec- ommended 5 servings a day after the SSS class. A previous study found that Mexican Americans in the Yakima Valley of Washington state, where this current study also took place, consumed an average of 4.96 servings of fruits and vegetables per day (Neuhouser, Thompson, Coronado, & Solomon, 2004). In comparison, the participants in this study consumed fewer servings of fruit and vegetables prior to the class but increased to 6.26 servings per day after SSS. Following SSS, participants better recognized the importance of eating healthy foods and being physically active, as meas- ured by the Healthy Lifestyle test. This may indicate that a healthy lifestyles class that is culturally sensitive has a positive effect on participant’s cognitive thinking regarding living a healthy lifestyle. The current pilot study demonstrated that Mexican immi- grants who participated in the class had positive outcomes of improved healthy lifestyle choices based on both objective and subjective testing methods. There are some limitations in the current study which include a small sample size, the possibility of the 24-hour diet recall being biased, and the classes not being offered throughout the year. The current study was held during the spring and summer months, allowing for more fruits and vegetables to be available at lower cost and more chances of nice weather for participants to play outside. Although the class does address physical activities that can be conducted indoors, it is recommended by the researchers that the class be repeated during the fall and winter to observe if seasonality has an effect on the outcome. The increasing obesity rates and lower insurance rates of the Hispanic population make this an area of immediate concern for health educators. Therefore, it is important that programs designed to meet their cultural needs are made available. This study evaluated one such program and found it to have a posi- tive effect on objective outcome measures associated with health parameters. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the staff and director of La Casa Hogar in Yakima, Washington for providing their time and facility for this project. References Barrera, R., Garza, J., Guido, C., Leija, M., Lester, M., Lobo, B., et al. (2002). Salsa, Sabor y Salud: A healthy lifestyles program for young Latinos. Facilitators Guide Los Ninos Y Los Chicos. San Antonio: National Latino Children’s Institute, in collaboration with Kraft Foods Corporations. Bermudez, O., Falcon, L., & Tucker, K. (2000). Intake and food sources of macronutrients among older Hispanic adults: Association with ethnicity, acculturation, and length of residence in the United States. Journal of the American Dieteti c Association, 100, 665-673. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00195-4 Biggard, J., Frederiksen, K., Tjonnelan, A., Thomsen, B., Overvad, K., Heitmann, B., et al. (2005). Waist circumference and body composi- tion in relation to all cause mortality in middle aged men and women. International Journal of Obesity, 29, 778-784. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802976 Block, G., Norris, J., Mandel, R., & DiSogra, C. (1995). Sources of energy and six nutrients in diets of low-income Hispanic-American women and their children: Quantitative data from NHANES, 1982- 1984. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 95, 195-208. Brown, S., Kouzekanani, K., Garcia, A., & Hanis, C. (2002). Culturally competent diabetes self-management education for Mexican Ameri- cans. Diabetes Care, 25, 259-268. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.2.259 Centers for Disease Control (2010). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system: Prevalence and trends d a t a 2010. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/list.asp?cat=OB&yr=2010&qkey=440 9&state=All Center for Prevention Research and Development (2005). An executive summary of the evaluation of the Salsa, Sabor y Salud program. Chicago: Kraft’s Foods. Crespo, C., Keteyian , S., Heath, G ., & Se mpos, C. (19 96). Leisure-ti me physical activity among US adults. Archives of Internal Medicine, 156, 93-98. doi:10.1001/archinte.156.1.93 Crespo, C., Smit, E., Anderson, R., Carter-Pokras, O., & Ainsworth, B. (2000). Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical in- activity during leisure time: Results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-1994. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 18, 46-53. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00105-1 Dixon, L., Sundquist, J., & Winkleby, M. (2000). Differences in energy, nutrient, and food intakes in a US sample of Mexican-American women and men: Findings from 3rd NHANES. American Journal of Epidemiology, 152, 548-557. doi:10.1093/aje/152.6.548 Doty, M. (2003). Hispanic patients double burden: Lack of health insurance and limited English. The Common Wealth Fund. Flegal, K., Ogden, C., & Carroll, M. (2004). Prevalence and trends in overweight in Mexican-American adults and children. Nutrition Re- views, 62, S144-148. Gilmer, T., Philis-Tsimikas, A., & Walker, C. (2005). Outcomes of project dulce: A culturally specific diabetes management program. Annals of Pharmacotherapy , 39, 817-822. doi:10.1345/aph.1E583 Guendelman, S., & Abrams, B. (1995). Dietary intake among Mexi- can-American women: Generational differences and a comparison with white non-Hispanic women. American Journal of Public Health, 85, 20-25. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.1.20 Huang, D., La To rre, D., Oh, C., Ha rven, A., Hub er, L., Leon, S., et al . (2008). An executive summary of the Afterschool Experience in Salsa, Sabor Y Salud evaluation 2007-2008. Los Angeles: CRESST/Uni- versity of CA. Lichtenstein, A., Appel, L., Brands, M., Carnethon, M., Daniels, S., Franch, H., et al. (2006). Diet and lifestyle recommendation revision  V. A. BENNETT ET AL. 374 2006: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association nutrition committee. Journal of the American Heart Association, 114, 82-96. Loria, C., Bush, T., Carroll, M., Looker, A., McDowell, M., Johnson, C., et al. (1995). Macronutrient intakes among adult Hispanics: A comparison of Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Mainland Puerto Ricans. American Journal of Public H ea l th , 85, 684-689. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.5.684 Mauldon, M., Melkus, G., & Cagganello, M. (2006). Tomando control: A culturally appropriate diabetes education program for Spanish- speaking individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus-Evaluation of a pilot project. The Diabetes Educator, 32, 751-760. Mier, N., Ory, M., Dongling, Z., Wang, S., & Furdine, J. (2007). Levels and correlates of exercise in border Mexican American population. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31, 159-169. Mokad, A., Ford, E., Bowman, B., Dietz, W., Vinicor, F., Bales, V., et al. (2003). Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 76-79. doi:10.1001/jama.289.1.76 Must, A., Spadano, J., Coakley, E., Field, A., Colditz, G., & Dietz, H. (1999). The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. Journal of the American Me d i cal Association, 282, 1523-1529. doi:10.1001/jama.282.16.1523 Neuhouser, M., Thompson, B., Coronado, G., & Solomon, C. (2004). Higher fat intake and lower fruit and vegetable intakes are associated with greater acculturation among Mexicans living in Washington State. Journal of the Ameri ca n Di e t et i c Association, 104, 51-57. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.015 Ogden, C., Carrol, M., Curtin, L., McDowell, M., Tabak, C., & Flegal, K. (2006). Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. Journal of the American Medical Association, 295, 1549- 1555. doi:10.1001/jama.295.13.1549 Slatttery, M., Sweeney, C., Edwards, S., Herrick, J., Murtaugh, M., Baumgartner, K., et al. (2006). Physical activity patterns and obesity in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 33-41. Venkat Narayan, K., Boyle, J., Thompson, T., Sorensen, S., & Wiliam- son, D. (2003). Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290, 1884- 1890. doi:10.1001/jama.290.14.1884 Wang, Y., & Beydoun, M. (2007). The obesity epidemic in the United States—Gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: A systematic review. Epidemiologic Reviews, 29, 6- 28. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxm007 Wilbur, J., Chandler, P., Dancy, B., & Lee, H. (2003). Correlates of physical activity in urban Midwestern Latinas. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 69-76.

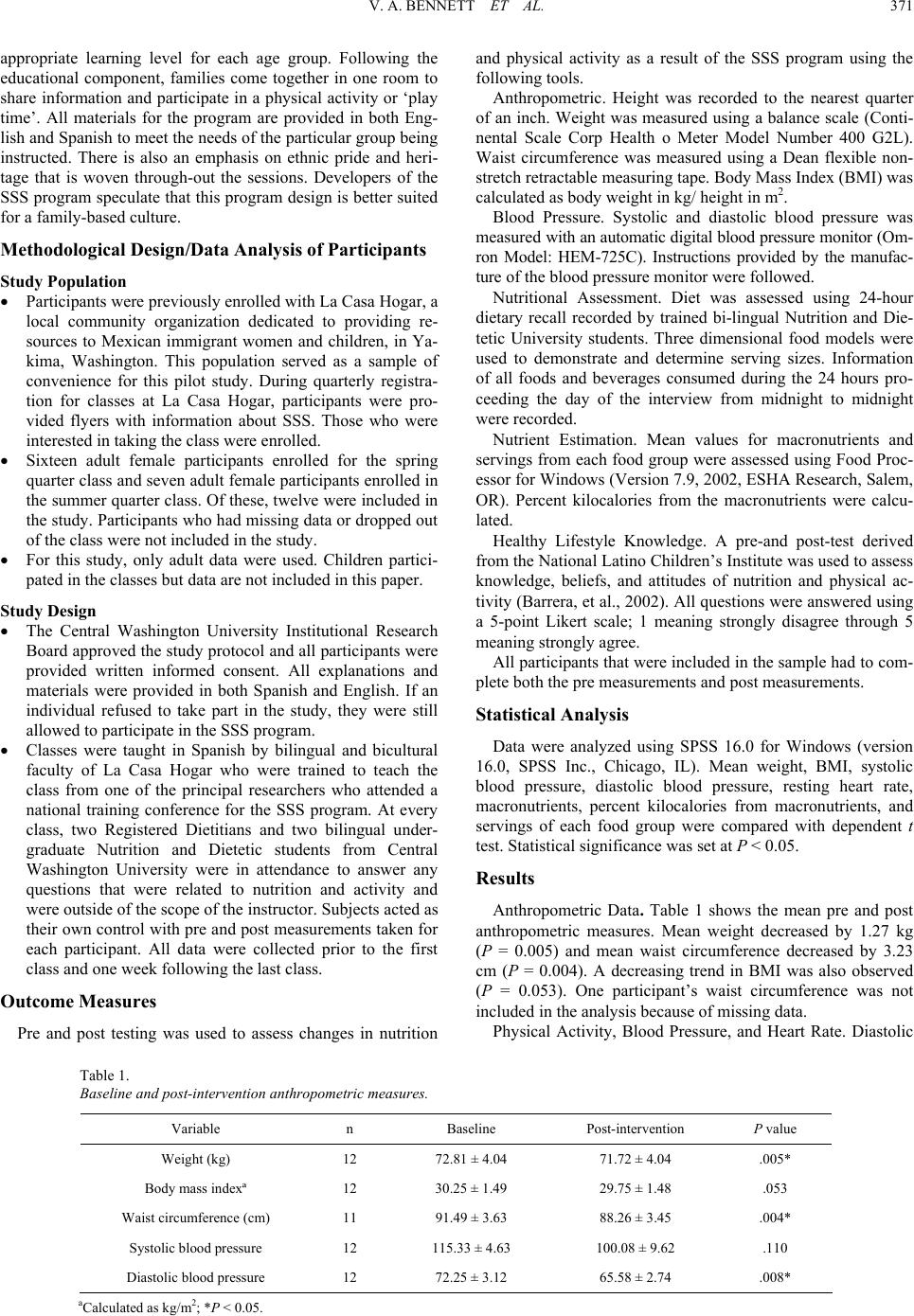

|