Journal of Environmental Protection, 2011, 2, 1046-1054 doi:10.4236/jep.2011.28120 Published Online October 2011 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks in Central Europe Tomas Gorner1,2, Martin Cihar1 1Institute for Environmental Studies, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic; 2Agency for Nature Conservation and Landscape Protection of the Czech Republic, Prague, Czech Republic. Email: mcihar@natur.cuni.cz, tomas.gorner@nature.cz Received August 2nd, 2011; revised September 4th, 2011; accepted October 5th, 2011. ABSTRACT This paper compares the views and attitudes of visitors to three key mountain national parks and Biosphere Reserves: Sumava National Park (Sumava NP, Czech Republic), Krkonose National Park (KRNAP, Czech Republic) and Karko- noski Park Narodowy (KPN, Poland). A large numbers of people visit these destinatio ns bo th in the summer (e.g. hikers and cyclists) and in the winter (e.g. hikers and skiers), which threatens sustainability and creates problems regarding the management of these areas. A comprehensive understanding of visitor use, including visitors’ attitudes and percep- tions, is fundamental for effective park management. Most research in these national parks is carried out during the summer season, therefore different results in the win ter season are expected . Using a standardised socio -environ mental survey we attempt to find seasonal differences between visitors and their opinions. A total of 2252 questionnaires were gathered. There were 13 common questions for these three national parks, three of them yielded significantly different results between the two seasons (visitors’ nationality, type of accommodation and financial costs). Other differences were detected in one or two national parks. Keywords: Sustainable tour ism, National parks, Mountain region s, Seasonal differences, Monitoring 1. Introduction The substantial growth of tourism clearly makes the in- dustry one of the most remarkable economic and social phenomena of the past century. One of the fastest grow- ing subsectors of tourism is nature-based tourism. Much of this growth concerns increasing numbers of people visiting protected areas [1]. Thus, the tourist trade de- rives benefits from the existence of protected areas. The relationships between tourism development and nature conservation are particularly important when tourism is partly or totally based on values derived from nature and nature resources. Tourism and nature conservation can be in conflict or in symbiosis. Symbiosis is the case when tourism and nature conservation are organised in such a way that both these disciplines derive benefits from the relationship [2]. There are many definitions of sustainable tourism development. One of these states that sustainable tourism is a positive approach intended to reduce the tensions and frictions created by the complex interactions between the tourism industry, visitors, the environment and the communities which are host to holidaymakers. This approach involves working for the longer viability and quality of both natural and human resources [3]. Tourists are central stakeholders of national parks and other protected areas [4]. The quality of visitors’ on-site experience is an important factor influencing and under- lying much sustainable tourism. Tourists, who are satis- fied and appreciative of visited settings and support ser- vices, help sustain the business in the region both as ex- isting and repeat visitors and through referrals [5]. Most of what is known about visitors and their inter- actions with each other and with the park environment has come from verbal surveys. Verbal surveys are still an essential tool for protected area visitor research. Many important questions can be addressed most efficiently and effectively by putting questions to visitors and ob- taining their answers. Some significant questions can only be addressed this way. Moreover, in some cases (e.g. politics and public relations), what people say can be more important than what they do [6].  Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks 1047 in Central Europe With regards tourism in the mountainous areas of Cen- tral Europe (i.e. the Alps, the Carpathians, the Giant Mountains, Sumava) there are two main tourist seasons: summer and winter. The main activities of winter visitors are downhill and cross-country skiing, while summer tourists prefer hiking and cycling. There is a long history of both summer and winter recreation in these regions, and many have been established as protected areas. The monitoring of tourism in the Czech Republic’s moun- tainous protected areas is located mostly in the national parks and Biosphere Reserves [7-9]. However, these studies are not pursued annually. The only systematic research is carried out by the Institute for Environmental Studies, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague. This Institute has collected data about tourists (both qualitative and quantitative) annually since 1997 in the Czech Republic’s two largest national parks (Sumava NP, Krkonose NP) [10-11]. In the remaining two national parks in the Czech Republic (Podyji NP and Ceske Svy- carsko NP) visitors were monitored in 2000 and in 2010. Moreover, questionnaires with local people and mayors of villages in national parks have also been pursued. The first monitoring of residents took place in 1997 and this has been repeated every fifth year. Nowadays, over 14 years of monitoring, including 11,850 completed ques- tionnaires with visitors and 1265 completed question- naires with local people have been collected and ana- lysed making it possible to observe several trends during this period. National parks in this study also have two main tourist seasons (winter and summer). However, the above men- tioned tourism monitoring takes place only in the sum- mer season. In practice annual data cannot always meet the requirements of decision and policy makers in tour- ism because the characteristics, attitudes and preferences of winter visitors can differ from summer visitors. There- fore it is necessary to take seasonality into account. This can be defined as a cyclical pattern that more or less re- peats itself each year. It usually refers to a temporal im- balance in demand, and may be expressed in terms of the number of tourists, their expenditure, and bed nights [12]. A good understanding of seasonality in tourism is essen- tial for the efficient management of tourism infrastruc- ture [13]. This seasonality could be caused by two ele- ments. The first is connected with regular variations in natural phenomena (temperature, snow, sunlight) during the year. People have different preferences on these con- ditions. The second element depends on social and insti- tutional factors and includes holidays, school schedules etc. [14-15]. Most of the studies describe seasonal varia- tions in tourism intensity that result in a number of nega- tive effects on the destination and in the economy of the region [16-17]. However, while the majority of seasona- lity studies focuses on quantitative aspects, the qualita- tive part could also be important and the timing of the survey may affect the results [18]. Regarding local peo- ple, changes in attitudes, depending on the season, has also been documented [18-19]. In these studies, the sur- vey was delivered in the quiet season (when residents are starting to run low on income) and in the peak season (when residents are sick of tourism). This study was prepared to find possible differences between the two main tourist seasons in these areas. In our hypothesis, we expected another accommodation preferences, attitudes to environmental problems, diffe- rent perception of tourism intensity and also higher fi- nancial costs in winter season. The research is financed by the Czech Ministry of the Environment with signifi- cant cooperation from the Administrations of National Parks. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Study areas (Figure 1) Sumava National Park is located in the south of the Czech Republic along the border with Germany and Austria. It includes the most valuable parts of the Su- mava Mountains. Covering an area of 68,064 hectares, Sumava NP is the largest national park in the Czech Re- public, and was established in 1991. The highest peak, Plechy, reaches to 1378 m. Sumava NP with the neigh- bouring Bavarian Forest National Park (24,250ha) covers approximately one-third of the whole of the forested area of the Sumava Mountains and the Bavarian Forest, form- ing together the largest forest complex in Central Europe. Secondary spruce forests are the dominating cover, but remnants of virgin spruce forests are still present at alti- tudes above 1200 m. Due to its location within densely populated Central Europe, and to its relatively high wild- life conservation, and to rich water resources, Sumava NP is often referred to as the “Green Roof of Europe”, the international significance of which is ever-increasing. This area was declared a Biosphere Reserve by UNE- SCO in 1990. The area of Sumava NP has been evacuated and re- inhabited several times in the past because of the Second World War and for political reasons. From the end of the 1940s to 1989 a special border zone between capitalism and socialism (“Iron Curtain”) and military areas was established at Sumava. In this area, the existing settle- ment structure was practically liquidated. After the Iron Curtain fell in 1990, there was a possibility to reach areas which had previously been inaccessible for a long time. However, pressure on the recreational use of the land is Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks in Central Europe Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 1048 Figure 1. Map of the survey localization. still increasing, as are summer and winter activities. Ap- proximately 600,000 tourists visit Sumava NP every year and more than two million now visit the whole Sumava region. Krkonose National Park (KRNAP) is situated in north-eastern Bohemia along the border with Poland. It was founded in 1963 and became the first national park in the Czech Republic, and now covers 54,969 hectares. Its goal is to preserve the natural values of the Krkonose Mountains (Giant Mountains), the highest mountain range in the Czech Republic (the highest peak Snezka is 1602 m). During its geological evolution, the northern and alpine ecosystems mixed here and the surprisingly rich biodiversity is reflected in the occurrence of a num- ber of endemic and glacial relicts. More than 80% of the park and its transitional zone is covered by forest eco- systems that are closely connected with the ecosystems of alpine grasses, sub-alpine peat bogs, glacial corries, and flower-rich mountain meadows. Since 1992 KRNAP, together with the neighbouring Karkonosze NP, has been included in the Bilateral Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO), a total area of 60,500 hectares. KRNAP is one of the most frequently visited areas of the Czech Republic and the most visited national park in the country with 5.4 million annual visitors. A study by Banas [20] deals with the amount of visitors per hectare of protected area and according to this study, KRNAP is the most exploited national park in Europe (98 people/ ha/year). Karkonosze National Park (Karkonoski Park Naro- dowy) (KPN) covers the highest part of the Giant Moun- tains on the Polish side and was established in 1959. Nowadays the park covers 5,575 hectares, mostly in the zones of upper sub-alpine forest and sub-alpine shrub and is generally confined within the main Krkonose Mountains range. Strict protection applies to the areas above the upper forest boundary (a total of 1717 ha). Furthermore 40 hectares of peat bogs are designated a Ramsar international wetland site. There are 30 animal, 18 vascular plant, 14 moss and 27 lichen species in- cluded in the Polish Red Book. Despite the extensive human exploitation of the Karkonosze wildlife and for- ests since the 15th century, many ecosystems, especially the mountainous ones, have retained their natural char- acter. However, the easily accessible lower parts of the mountains have significantly changed. As in the Czech part of the Giant Mountains, the main anthropogenic threats for Karkonosze wildlife are air pollution (mainly SO2) and tourism. The closest tourist centres are Karpacz and Szklarska Poreba. Both are located on the park’s border, and both are very popular as summer and winter vacation spots. [21]. The south-west of Poland is densely populated and the park is a popular tourist destination. Over 2.5 million people visit every year, mainly from Poland and Germany. They can use 112 km of marked hiking routes (some of them can also be used for moun-  Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks 1049 in Central Europe tain biking), 10 ski lifts and 12 guest houses. 2.2. Qualitative Research The questionnaire was split into six sections with 25 questions in total. The opening section involves informa- tion about how many times the visitors had been to the park and which season they preferred to visit. The se- cond section refers to transport and accommodation. There are questions about means of transport to and in the park and about place and type of accommodation including cost of living. One question is designed to de- termine visitor satisfaction with the cost of living. We used a five-point Likert scale [22] ranging from very dissatisfied to very satisfied. The following part used a five-point Likert-type scale too and asked respondents to rate the importance of their motivation for visiting the park. We also find here the activities visitors want to take part in. The section about environmental awareness com- prises visitor knowledge of ecological problems in the park and an evaluation of the state of the environment. Further parts elicited information about tourist evaluation of conservation and tourism management in the park. The last question provided a check on visitors’ percep- tion of tourism intensity on hiking tracks and in centres and their vicinity. The final part seeks sociodemographic data about the visitors (age, gender, place of residence, occupation and education). The structure of the ques- tionnaire was very similar in all selected national parks. Direct interviews were used in this study with visitors interviewed in the field at selected crossings of hiking trails where monitoring of hikes was available. There were four crossings in KPN (Kopa, Śląski Dom, Schro- nisko pod Łabskim Szczytem and Szrenica), five in KRNAP (the viewpoint at Kozi hrbety, Lucni bouda, Ruzohorky, crossroad U ctyr panu and crossroad under Snezka) and five in Sumava NP (Antygl, Breznik, Hor- ska Kvilda, Kvilda and Modrava). The observed period was nine days (five weekdays and two weekends) in the middle of August from 9 am to 6 pm. In winter (in the middle of February in KPN and KRNAP and during five weekends in January and February in Sumava NP) tour- ists were interviewed from 9 am to 4 pm. As to the me- thod of selecting people for the poll, this was carried out on a random basis and the questionnaires were strictly anonymous [23]. The respondents also had to be over the age of 15. The completed questionnaires were processed in the form of database files using Microsoft Access and Mi- crosoft Excel. Statistical Programme Statgraphics Plus, version 5.1 was used for statistical evaluation of these data. We used the χ2 test for evaluating cases where re- sults differed between summer and winter seasons. 3. Results and Discussion In the course of our research for this study 2252 com- pleted questionnaires were gathered, computer processed and analysed (KPN 476, KRNAP 695, Sumava NP 1081). The refusal rate was low (9.4%) and the most common reason for refusal was “no time” (45%), while “no inter- est” accounted for 38%. There were 13 common ques- tions for these three national parks. Three issues yielded significantly different results (P < 0.05) between the two seasons in all monitored national parks: the visitor’s na- tionality, type of accommodation and financial costs. All detected statistically significant differences are summa- rised in Table 1. In the case of visitors’ nationality, domestic tourists prevailed in all three national parks (Table 2). Foreign visitors preferred the summer season in Sumava NP in contrast to the winter season. Most were German (more than 50% from all foreigners) and Slovakian (almost 20%). The same situation occurred in KRNAP. In sum- mer, approximately one-third of all respondents were foreigners (predominantly German and Polish). In winter, only every fifth visitor to this national park was a for- eigner. Apart from this, foreigners visited KPN more frequently in winter in comparison with the summer season. In the case of neighbouring KRNAP and KPN, German tourists preferred the Polish side of the Giant Mountains in winter months and they visited the opposite side of the border (KRNAP) in the summer season more frequently. With regard to visitors’ type of accommodation, it is also possible to observe statistically different preferences between the summer and winter seasons (Figure 2). Re- search in both Czech national parks pointed to similar results and differed from the Polish national parks. In KRNAP and Sumava NP there was a substantial increase in the “Other” category in the summer season (most common types of accommodation in this category was staying with relatives, friends and outdoors) and a de- crease in the “Company property” category. Visitors in Sumava NP also gave priority to hotels in the winter season. KPN visitors preferred the “Other” and “Bed and breakfast (pension)” categories in winter in comparison with the summer months. Of course, the summer season provides a new and indispensable type of accommoda- tion—camping. This type of accommodation is mostly typical for Czech tourists; 10% of Sumava NP visitors spent time in camps during their summer holidays. For example, only 1.5% of visitors in the neighbouring Bay- erischer Wald National Park spent their time in this type of accommodation [24]. This number is also decreasing, our annual research pointed to a regular decline from Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks in Central Europe Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 1050 Table 1. Comparison of winter and summer visitors in Karkonoski Park Narodowy (KPN), Krkonossky NP (KRNAP) and Sumava NP (NPS) (X - statistical difference between summer and winter survey, P < 0.05). KPN KRNAP NPS Age group - - - Nationality - - - Gender - - - Education - - - Occupation - - - Nationality X X X Size of the town X - X Type of accommodation X X X Length of stay X - - Means of transport - X - Financial costs (FC) X X X Satisfactory with FC X - - Perception of tourism intensity on hiking tracks X - X Perception of tourism intensity in the centres - X X Table 2. Visitors’ nationality in % (W-winter, S-summer). KPN (W) KPN (S) KRNAP (W)KRNAP (S) NPS (W) NPS (S) Czech Republic 3.6 4.7 80.2 65.7 97.5 94.4 Germany 29.0 6.2 15.4 23.3 1.0 3.9 Poland 67.4 85.5 1.2 7.9 0.0 0.0 Others 0.0 3.6 3.1 3.2 1.5 1.7 Figure 2. Type of accommodation of visitors.  Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks 1051 in Central Europe 20% in 1997. The fall in camp visitors could be traced not only in Sumava NP but also in other Czech national parks (KRNAP 3.9% in 1997 versus 2.3% in 2010; Ceske Svycarsko National Park 21.3% in 2000 versus 14.2% in 2010). The Czech Statistical Office also notes the annual decline of accommodation in campsites in the whole Czech Republic, in its Statistical Yearbooks of the Czech Republic (accessible from www.czso.cz). Young people are especially keen on sleeping outdoors. They have a high regard for the temporary overnight campsites that were recently established for tourists who travel through Sumava on the red marked trail, leading along- side the national border from Nova Pec all the way to Zelezna Ruda. The question concerning financial costs was connected to this issue. Winter visitors spent more money in com- parison with summer tourists as we expected in the hy- pothesis. The most significant differences were observ- able in Sumava NP. More than one-third of visitors spent their time in hotels in the winter. In the summer, staying in camps, with relatives and friends and sleeping out- doors is very popular and 38.7% of summer visitors es- timated their expenses on board and lodging per person per day as less than 300Kc (€12.5). Only 29.7% of win- ter tourists paid the same price. On the other hand, 24.3% of winter visitors spent more than 800Kc (€33) (apart from 11.5% of summer tourists). A very similar situation was found in the other two national parks. With the ex- ception of accommodation, other activities are also more expensive in winter in these areas. It is necessary to mention ski-lift fares (almost one-third of respondents stated they used ski-lifts at least once during their stay in a national park) and more frequent indoor activities (swimming pools, bowling, etc.). Focusing on the sociodemographic characteristics of visitors, this study revealed no seasonal differences in age groups, gender, education and occupation of tourists. Another situation arose with regards the size of the town where visitors live. It detected statistically signifi- cant differences between summer and winter visitors in KPN and Sumava NP (Figure 3). In Polish national parks visitors from the bigger towns prevailed (100,000 - 1 million) in the winter season. This is due to the geo- graphical position of this area—it is located approxi- mately 120 km from Wroclaw, the main city of south- western Poland (population 633,000). Tourists from cit- ies with a population of more than one million (the near- est being Prague, Berlin and Warsaw) were also rela- tively frequent (16.3%). Apart from this, more people from smaller towns visited KPN (10,000 - 100,000) in the summer season. A similar situation was observed in KRNAP. One-third of winter visitors came from cities with a population of more than one million people (pre- dominantly Prague), compared to 22% of summer tour- ists. Sumava NP showed an inverse trend—only 17% of winter visitors were from Prague. Sumava does not offer such winter facilities (i.e. ski lifts) as the Giant Moun- tains. Moreover, many people go to closely located ski resorts in the Alps. The winter season rather attracted people from neighbouring districts (from towns with a population of 2000 - 10,000). Seasonal variations were also reported in the expected length of stay (Figure 4). The most frequent period of stay for all three parks was one week. Visitors to the Gi- ant Mountains (KPN, KRNAP) preferred one-day visits in summer more than in winter. In winter one week stays Figure 3. Size of the town where visitors live. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks 1052 in Central Europe Figure 4. Expected length of stay of visitors. prevailed. The Giant Mountains offer the best skiing op- portunities in the surrounding areas. Visitors travel to this area from more distant places, and a one day visit is also not economically advantageous. Operators of ac- commodation facilities are also unwilling to put visitors up for less than three days, especially in winter. The situation in Sumava NP was quite the opposite. Accom- modation within the park is limited and many tourists come from the nearest surroundings (see previous para- graph). Concerning means of transport to the national parks, the car was the most popular in both seasons (Figure 5). The highest car dependency was detected in Sumava NP, especially in winter. Apart from this, KPN and KRNAP visitors used cars mostly in the summer. In these areas other means of transport played a more important role. There is a better railway connection on the Polish side of the Giant Mountains (to Szklarska Poreba), therefore almost 30% of winter visitors to KPN used the train as a means of transport to this destination. The study detected significant seasonal difference in this topic in KRNAP. There was a substantial increase in tourists who travelled to this area with travel agencies in the winter. The winter season was also typical for package holidays (almost one-quarter of respondents) whereas summer visitors preferred individual transport. Visitors’ perception of tourism intensity also showed significant seasonal differences. Compared with the sum- mer, fewer winter tourists evaluated tourism intensity as high and disturbing in Sumava NP (39.1% versus 52.2% in tourist centres; 21.6% versus 43.8% on hiking tracks). Similar results were obtained from KPN. Approximately 13.2% of winter visitors evaluated tourism intensity on hiking tracks as high and disturbing, whereas almost 25% of summer tourists replied in the same way. In contrast, in KRNAP, the feeling that tourism in tourist centres is too concentrated was more widely held by tourists in the winter season (27.4%) than in the summer (22.9%). This issue is closely connected with the carrying capacity of these areas. Four categories of carrying capacity have been identified: physical, eco- logical, economic and perceptual. The latter is defined as the level of use before a decline in the users’ recreational experience [25]. Martin and Uysal [26] assigned these types of carrying capacity to each stage of the tourism life cycle. They also highlighted the most important fac- tors for each stage. Physical carrying capacity is limiting for the early stage. Ecological and perceptual aspects (closely connected with economic ones) become in- creasingly important in maintaining an attraction in its mature phase and in preventing its decline. These results point to different characteristics of sum- mer and winter tourists. According to this study, the tim- ing of the survey could affect the results of visitors’ qua- litative research. 4. Conclusions Tourists’ attitudes and preferences are important because they predict tourist satisfaction and future behaviour. Satisfied visitors are more likely to revisit an area. The results of this study show significant differences in char- acteristics and preferences of visitors in two main tourist seasons in three mountainous national parks. According to this study, the timing of the survey administration C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks 1053 in Central Europe Figure 5. Means of transport to the national park. could affect the results of visitors’ qualitative research. These results of qualitative surveys in winter and sum- mer tourist seasons have been, and will be, very impor- tant for several reasons. First, they reveal various dy- namic user profiles and attitudes between two main tour- ist seasons in the selected national parks. Whereas most research is carried out during the summer season in these areas, this study demonstrates that the results from the relatively economically crucial winter season may be different. The research found three significantly different items depending on the timing of the survey: visitors’ nationality, type of accommodation and financial costs. Domestic tourists prevailed in all three national parks. More foreigners visited Sumava NP and KRNAP in summer than in winter, while the situation in KPN was strictly opposite. Both Czech national parks evinced similar seasonal differences in accommodation (an in- crease in the “Other” category in the summer season and a decrease in the “Company property” category in this period), visitors to Sumava NP also gave priority to ho- tels in the winter season. KPN visitors preferred the “Other” and “Bed and breakfast” (pension) categories in winter in comparison with the summer months. Winter visitors spent more money in comparison with summer tourists. Concerning carrying capacity, in KRNAP, the feeling that tourism is too concentrated was more widely held by tourists in the winter season than in the summer season. The carrying capacity of visitor numbers seems to have nearly been reached. Some management options like periodic traffic limitations, restrictions of new construc- tion development (and supporting improvement of exist- ing facilities) or park entrance fees could improve this situation. Tourists also had different perceptions of environ- mental problems in the summer and winter seasons. Win- ter tourists did not see tourism as a threat, in contrast to summer research at the same site. Management of the park should focus on consistency and the direct and in- direct effects of summer and winter tourist seasons, as well as tourist awareness of the negative impacts of tour- ism on the sensitive mountain environment in winter (e.g. by using information centres, brochures, tourist guides, rangers, environmental information system of the park administrations). Results from this study, together with data about local residents in Czech national parks, provide appropriate indicators of sustainable development in (not only) Czech protected areas. The outcomes of the survey are being used for design priorities for the management of environmental protection at local, regional and national levels. REFERENCES [1] R. Buckley, “Tourism in the Most Fragile Environ- ments,” Tourism and Recreation Research, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2000, pp. 31-40. [2] G. Budowski, “Tourism and Environmental Conservation, Conflict, Coexistence, or Symbiosis?” Environmental Conservatism, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1976, pp. 27-31. doi:10.1017/S0376892900017707 [3] B. Bramwell and B. Lane, “Sustainable Tourism: An Evolving Global Approach,” Journal of Sustainable Tou- rism, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1993, pp. 1-5. [4] R. Butler and S. Boyd, “Tourism and National Parks: Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Seasonal Differences in Visitor Perceptions: A Comparative Study of Three Mountainous National Parks 1054 in Central Europe Issues and Implications,” Wiley, Chicester, 2000. [5] C. Cooper, J. Fletcher, A. Fyall, D. Gilbert and S. Wan- hill, “Tourism. Principles and Practice,” Pearson Educa- tion, Edinburgh, 2005. [6] D. N. Cole and T. C. Daniel, “The Science of Visitor Management in Parks and Protected Areas: From Verbal Reports to Simulation Models,” Journal for Nature Con- servation, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2003, pp. 269-277. doi:10.1078/1617-1381-00058 [7] D. Kusova, J. Tesitel, K. Matejka and M. Bartos, “Bio- sphere reserves—An Attempt to Form Sustainable Land- scape (A Case Study of Three Biosphere Reserves in the Czech Republic),” Landscape and Urban Planning, Vol. 81, No. 1, 2008, pp. 187-197. [8] J. Stursa, “Impacts of Tourism Load on the Mountain Environment (A Case Study of the Krkonoše Mountains National Park—The Czech Republic),” Proceedings Con- ference Monitoring and Management of Visitor Flows in Recreational and Protected Areas, Vienna, 30 January-2 February 2002, pp. 364-370. [9] J. Suchy, et al., “Determination of Actual Attendance and Its Annual Dynamics in Krkonose Biospheric Reserve,” Final Report of the Research Project VaV/610/8/00, Pra- gue, 2002. [10] M. Cihar and V. Trebicky, “Analysis of the Monitoring of Recreational Activities in the Central Part of Sumava National Park,” Final Report of the Research Project by the MoE, Prague, 1997. [11] M. Cihar, J. Stursa and V. Trebicky, “Monitoring of Tourism in the Czech National Parks,” Proceedings Con- ference Monitoring and Management of Visitor Flows in Recreational and Protected Areas, Vienna, 30 January-2 February 2002, pp. 240-245. [12] R. Butler, “Seasonality in Tourism: Issues and Prob- lems,” In: A. Seaton, Ed., Tourism: The Status of the Art, Wiley, Chichester, 1994, pp. 332-339. [13] E. Koc and G. Altinay, “An Analysis of Seasonality in Monthly per Person Tourist Spending in Turkish Inbound Tourism from a Market Segmentation Perspective,” Tour- ism Management, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 227-237. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2006.01.003 [14] R. Hartman, “Tourism, Seasonality and Social Change,” Leisure Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1986, pp. 25-33. doi:10.1080/02614368600390021 [15] J. C. Parrilla, A. R. Font and J. R. Nadal, “Accommoda- tion Determinants of Seasonal Patterns,” Annals of Tour- ism Research, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2007, pp. 422-436. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2006.10.002 [16] D. Snepenger, B. Houser and M. Snepenger, “Seasonality of Demand,” Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 17, No. 4, 1990, pp. 628-630. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(90)90037-R [17] S. Krakover, “Partitioning Seasonal Employment in the Hospitality Industry,” Tourism Management, Vol. 21, No. 5, 2000, pp. 461-471. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00101-6 [18] T. Young, M. Thyne and R. Lawson, “Comparative Study of Tourism Perceptions,” Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 26, No.2, 1999, pp. 442-445. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00087-5 [19] C. J. Liu and T. Var, “Resident Attitudes toward Tourism Impacts in Hawaii,” Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 13, No. 2, 1986, pp. 193-214. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(86)90037-X [20] M. Banas, “Sustainable Tourism in European Mountain Protected Areas,” Report about a project supported by Alfred Toepfer Natural Heritage Scholarship and EU- ROPARC Federation, 2006. [21] A. Raj, “Karkonoski Park Narodowy,” Multico Oficyna Wydawnicza, Jelenia Gora, 2009. [22] E. Babbie, “The Practice of Social Research,” Wadsworth, Belmont, 2004. [23] P. Gavora, “Introduction to thePedagogical Research,” Paido, Brno, 2000. [24] M. Mayer, M. Müller, M. Woltering, J. Arnegger J. and H. Job, “The Economic Impact of Tourism in Six German National Parks,” Landscape and Urban Planning, Vol. 97, No. 2, 2010, pp. 73-82. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.04.013 [25] F. B. Goldsmith, “Ecological Effects of Visitors in the Countryside,” In: A. Warren, F. B. Goldsmith, Eds., Con- servation in practice, Wiley, New York, 1974, pp. 217- 231. [26] B. S. Martin and M. Uysal, “An Examination of the Rela- tionship between Carrying Capacity and the Tourism Lifecycle: Management and Policy Implications,” Jour- nal of Environmental Management, Vol. 31, No. 4, 1990, pp. 327-333. doi:10.1016/S0301-4797(05)80061-1 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP

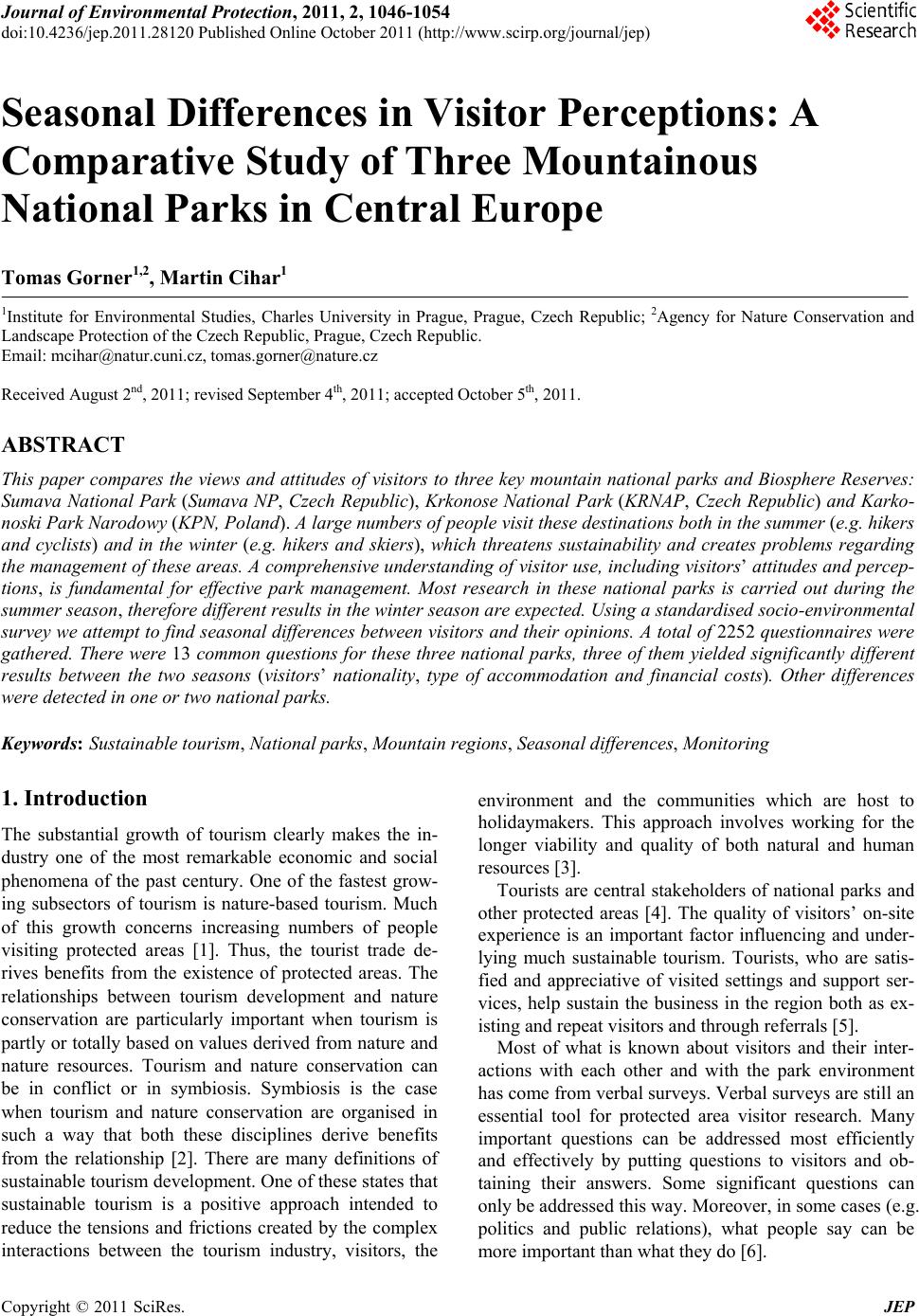

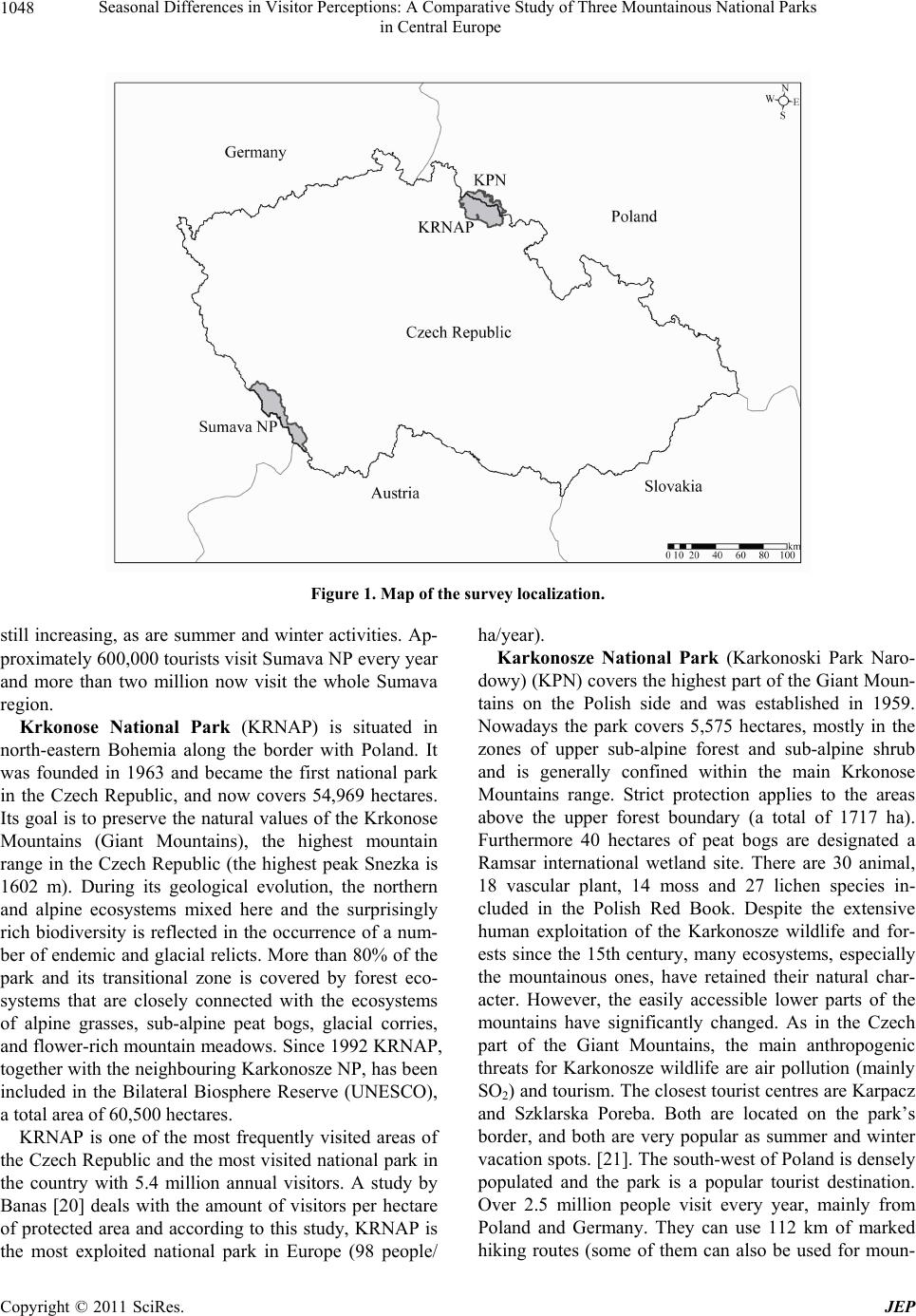

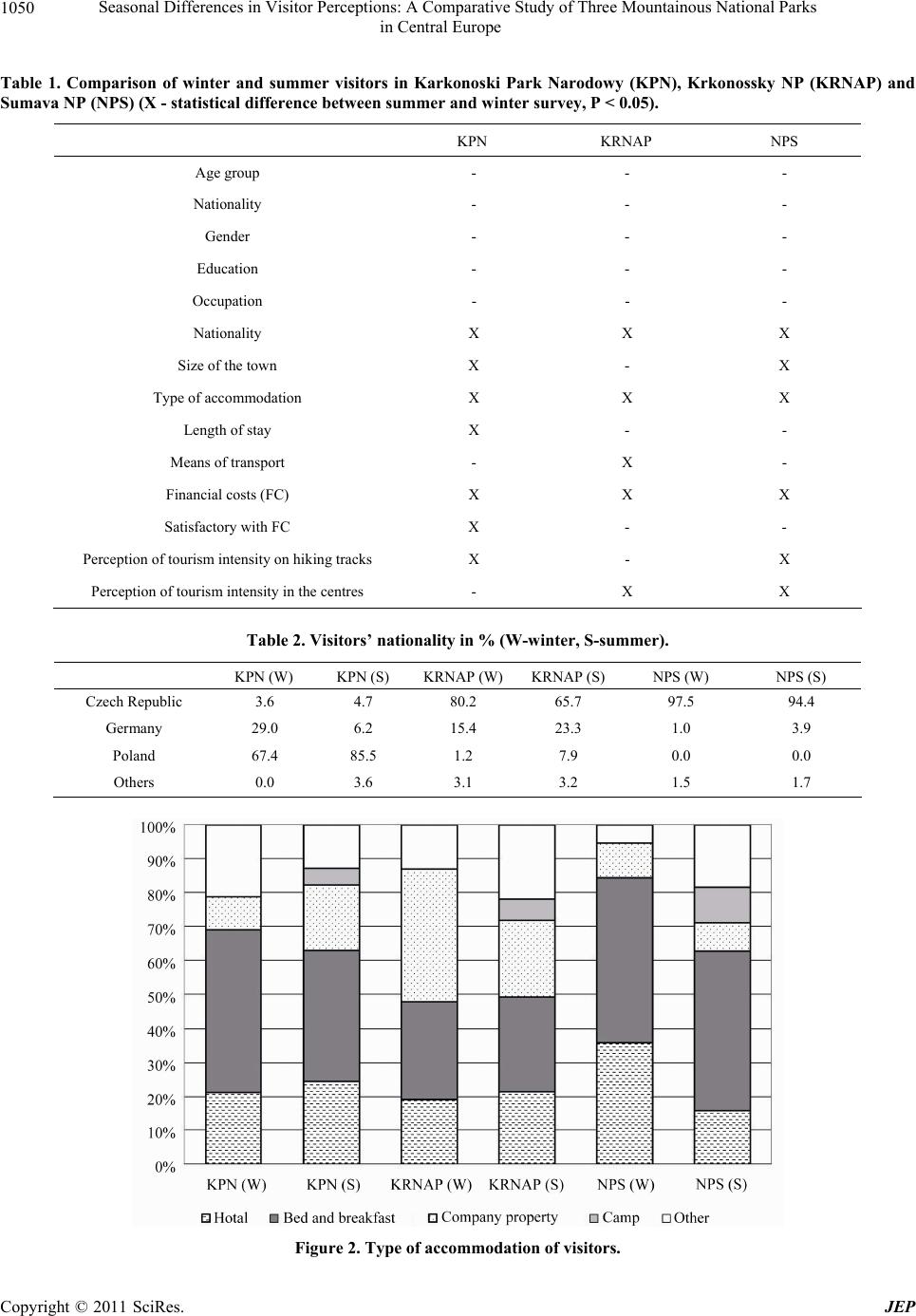

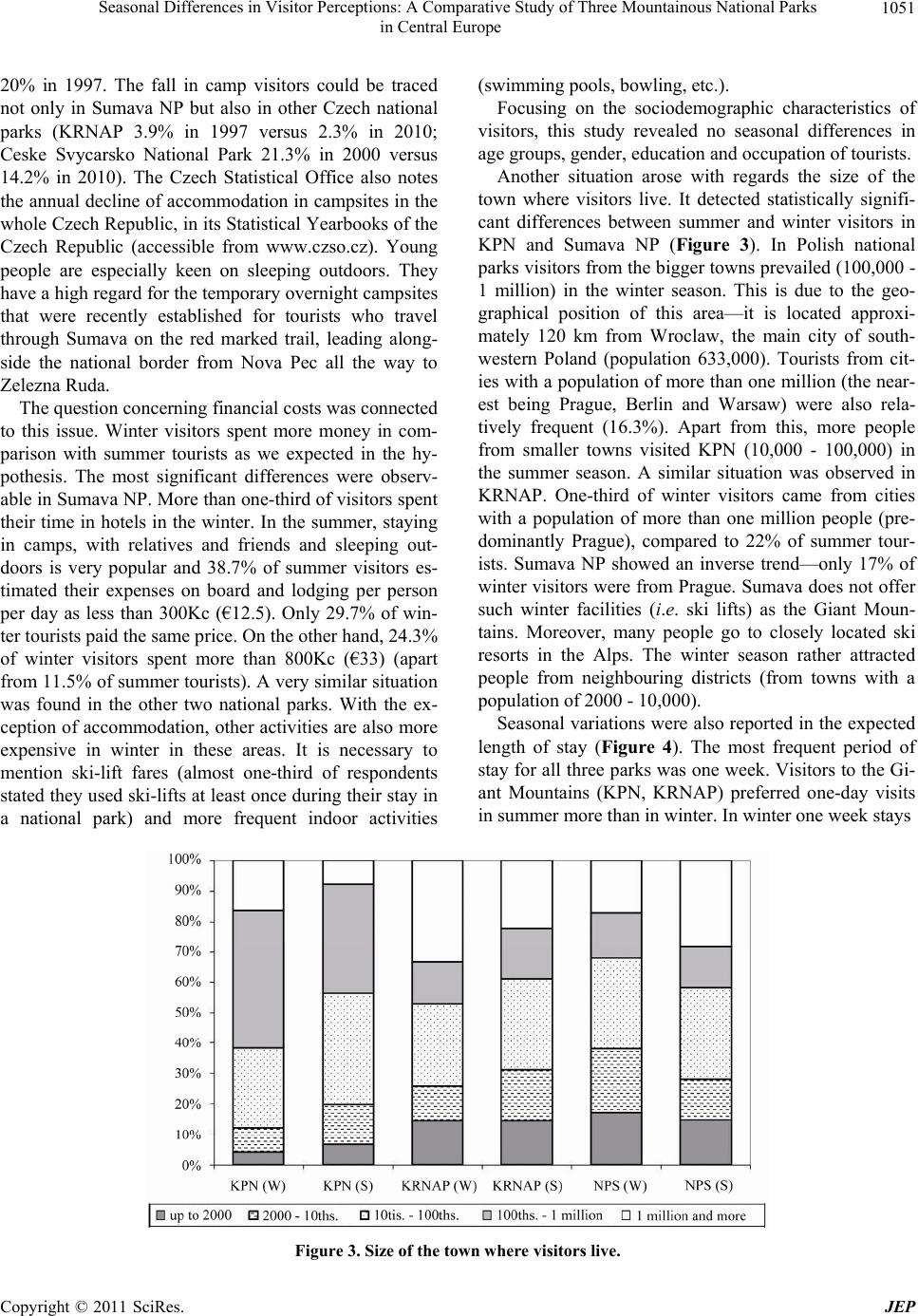

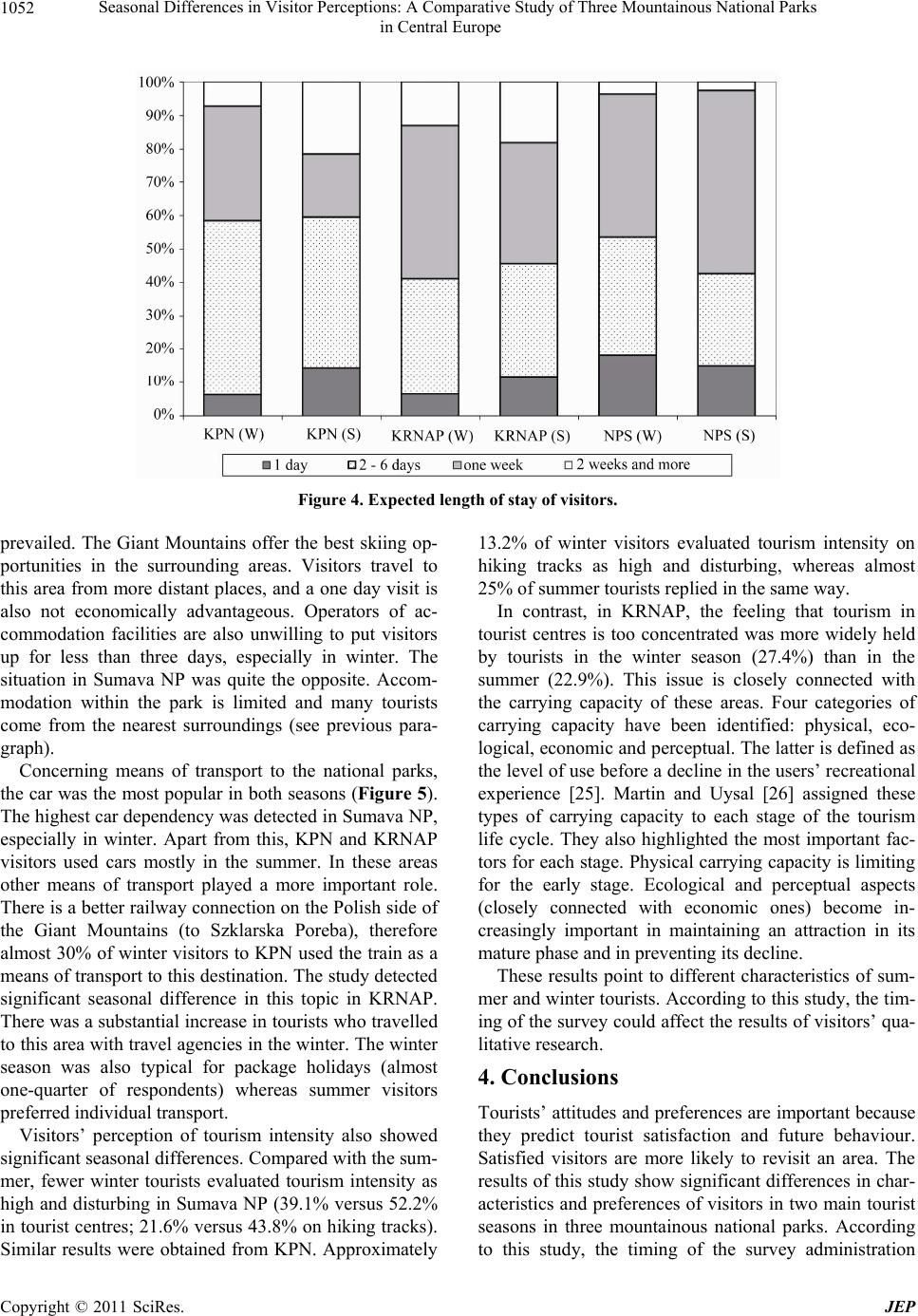

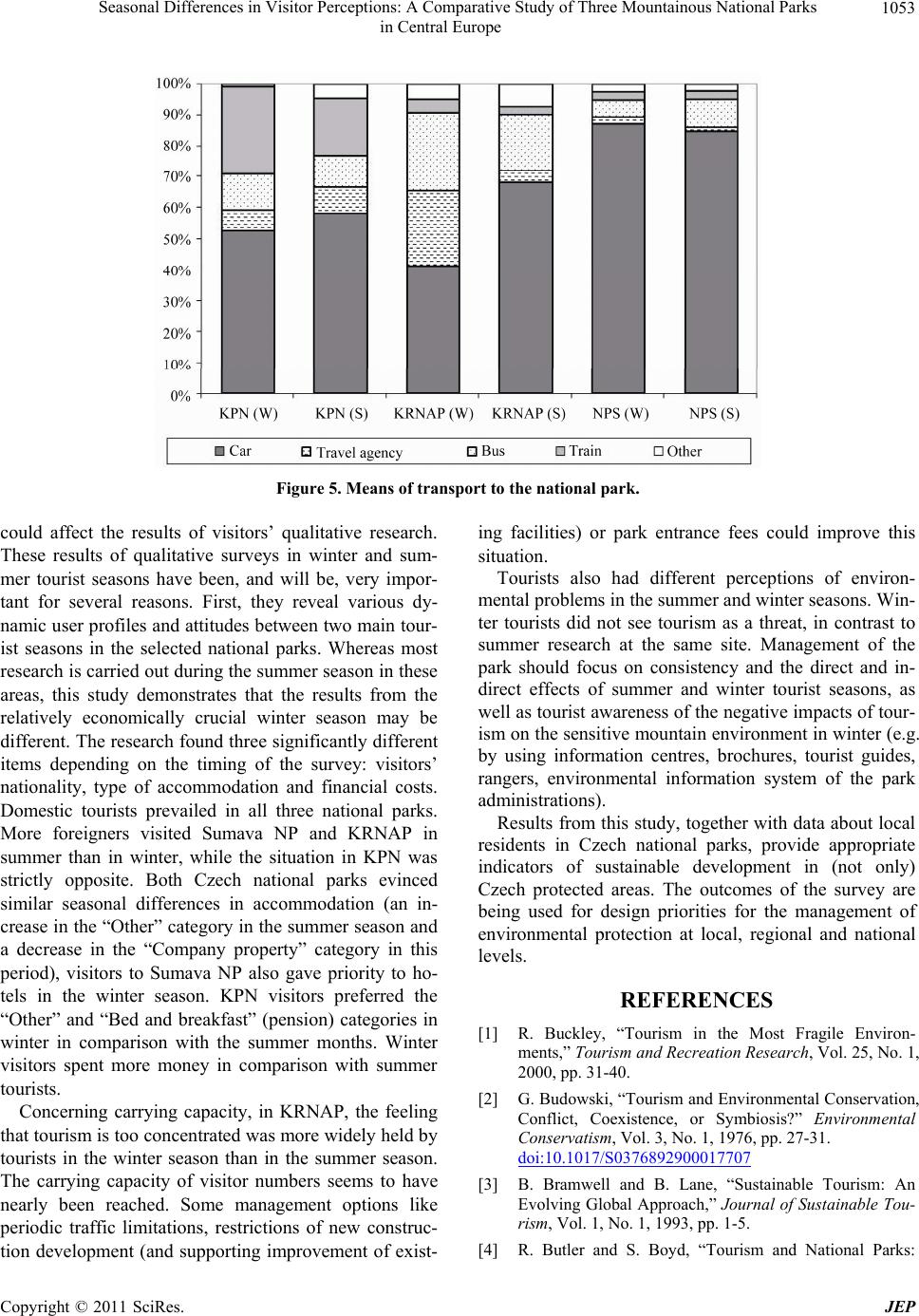

|