Vol.1, No.3, 135-144 (2011) doi:10.4236/ojas.201 1.13018 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ Open Journal of Anim al Sciences Qualified “in shelter” dogs’ evaluation and training to promote successful dog-human relationships Marilena Sticco1, Roberto Trentini2, Pia Lucidi3* 1 Doctor in Animals’ Welfare and Protection, L’Aquila (AQ), Italy; 2 “G. Caporale” Experimental Zooprofilattico Institute of Abruzzo and Molise, Teramo, Italy; 3Department of Comparative Biomedical Science, School of Veterinary Medicine, Teramo, Italy; *Corresponding Author: plucidi@unite.it Received 26 July 2011; revised 5 September 2011; accepted 21 September 2011. ABSTRACT The phenomenon of dogs’ relinquishment in Italy has become a social evil, although many laws exist to regulate animal protection and lately, the act of abandonment has become criminalised (law n.189/2004, enforced by law n.201/2010). Adop tion fro m shelters seems t o be the only way to have a controlled, microchipped population of dogs, as well as limiting con- finement and euthanasia. After being asked to simplify the previous Ethotest © version [13] by many shelter operators and veterinarians, the authors aimed at analyzing the effectiveness of an improved model to test dogs’ behavioral ap- titude matching the expectations of a hypo- thetical adopter. The new version improves the test feasibility by the elimination of a previous computer-based program, and by the introduc- tion of new items such as hierarchical behavior towards food. In this study dogs housed in the sanitary shelter of L’Aquila (Abruzzo, Italy), of different age and sex, either sterilized or not, and belonging to different breeds or cross- breeds, were tested. All the dogs adopted from the shelter were monitor ed fo r one y ear after the adoption by both phone interviews and home visit. The study aimed at analyzing if the shelter dogs showed a good and consistent behavior after adoption in the new environment. The re- sults demon stra te d th at apart from a predictable relinquishment and an unfortunate case of abuse, none of the dogs adopted showed any unwanted behaviors such as house soiling, jumping up, separation-related and aggressive behaviors; this made their stay in the family a desirable, exciting experience independently of the dog sex, age, and the family composition. The authors stress the necessity of every shel- ter, together with the veterinary cares, for a professional expert at dogs’ behavior who can efficaciously prevent behavioral problems, eventually train the dogs and afford the pairing with humans in a competent, qualified manner. Keywords: Adoption; Behavioral Test; Shelter Dogs; Training 1. INTRODUCTION All over the world the overpopulation of stray dogs is a concern due to a number of dog attacks on infants and adults [3,6]. Who is to blame for the failure of control of stray dogs? In most cases the stray dogs overpopulation results from housedogs and from irresponsible owner- ship [17,20]. In fact, not all the owners sterilize their dogs and, worst of all, they are allowed to roam at the time of reproduction. This results in the possibility that those dogs mate and give birth to unwanted puppies, whose final destination is the abandonment without a microchip for their identification. In Italy, the law n. 281 regulates the capture and ster- ilization of stray dogs since 1991. Consequently to the enacting of this law, euthanasia of unwanted roaming dogs has been forbidden, unless it can be demonstrated that they are dangerous or incurable. This gave rise to the establishment of a multitude of long-term shelters where unattended dogs are placed in questionable condi- tions, waiting for an adoption that sometime never oc- curs. It has been estimated that the number of strays in Italy amounted to 600,000 in 2009 (source: Italian Min- istry of Health, www.salute.gov.it), but the problem of unwanted dogs is a common, widespread topic all over the world with millions of abandoned dogs ending up in shelters [2]. In this study, the authors evaluated dogs’ traits that are  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 136 the requisites for living together amicably with humans by simplifying the already published program Ethotest©, which was realized in order “to lay the foundations for a more flexible selection of dogs to be used as co-thera- pists” [13]. In fact, after several shelters in different Ital- ian cities adopted Ethotest©, many operators released feedback asking for a revised, simplified program (here- inafter Ethotest-R). Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a more simplified method of selection and to sponsor the need for a qualified shelter caretaker to per- form in order to improve the welfare of dogs and safety of the adoptions. To analyze dogs’ behavioral traits, we used the general outline of the previous Eth- otest© con- sidering that, as proved by Hsu and Serpell [9], there are only the following few factors stable and consitent across different populations: stranger-directed fear, stranger-directed aggression, owner-directed aggression, non-social fear, dog-directed fear or aggression, train- ability, and attachment. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Animals The Ethotest-R version was carried out on 32 shel- tered dogs (see Table 1); 24 of them crossbreed and 8 belonging to the following breeds: Abruzzi’s Shepherd dog, American Staffordshire Terrier, English Setter, German Shepherd, Maremma Hound, Pointer, and Sibe- rian Husky. The dogs were housed at the small shelter of L’Aquila health department (ASL 04) where we tested all the dogs hosted. According to the Italian law for straying control, all captured dogs are microchipped be- fore their entry to the kennel, and then lodged in isola- tion pens. Here, they are submitted to a blood test and checked for anti-leishmania antibodies, vaccinated and treated for parasites. After quarantined for a certain pe- riod of time, they are transferred to other pens waiting for being adopted. The pens, provided with external ar- eas, could house several dogs together, depending on how compatible they are with each other; otherwise some subjects can be housed in isolation (i.e., the American Staffordshire Terrier in our study). This small regional shelter is unique in the Italian scenario, because a qualified staff efficaciously cares for the dogs. The dogs are fed on commercial dog food, pens are cleaned more than once a day, and a qualified veterinarian who cares for the animals’ healthiness peri- odically visits all dogs. The veterinarian is available when- ever an emergency arises. For any other needs, namely ethological and physiological needs, there is a technician qualified in Animals’ Protection and Welfare (one of the Authors-hereinafter Operator 1); this Operator assists the dogs by monitoring temperament and social interaction Table 1. Characteristic of the dogs subjected to Ethotest-R. ID n.Name Breed Age Sex SizeTime in shelter 1Ada Mix 10 m ♀ spayed M6 m 2Bella Mix 8 y ♀ spayed M2,5 y 3BianconeAbruzzi Shepherd 11 y ♂ neutered M5 y 4Bobo Mix 10 m ♂ intact M6 m 5BraccoPointer 6 y ♂ intact M5 y 6Didi Mix 3 y ♀ spayed L2,5 y 7Eva English Setter 4 y ♀ spayed M2 y 8Frank Mix 8 y ♂ intact M4 y 9Gilda Mix 8 m ♀ spayed M3 m 10GregorioMix 10 y ♂ neutered G1 y 11GrethelMix 2 y ♀ spayed L2 y 12HanselMix 2 y ♂ intact L2 y 13Jack Am. Staff. Terrier 7 y ♂ intact L1 y 14Jamaica Mix 3 y ♀ spayed L2,5 y 15Lana Siberian Husky 5 y ♀ spayed L2 y 16Leon Mix 5 m ♂ intact L3 m 17Liz Mix 6 m ♀ intact M3 m 18LouiseMix 4 y ♀ spayed M3,5 y 19LupizzaGerman Shep. 8 y ♀ spayed L1 y 20 ManoloMaremmaHound 9 y ♂ neutered M5 y 21 Mitzy Mix 3 y ♀ spayed L3 y 22Nina Mix 7 y ♀ spayed M6 y 23OlguitaEnglish Setter 3 y ♀ spayed M5 m 24Petra Mix 3 y ♀ spayed L2,5 y 25Ripa Mix 4 y ♀ spayed M3,5 y 26Salvo Mix 2 y ♂ intact L1, 5 y 27Secco Mix 5 y ♂ intact S3 y 28SnoopyMix 5 m ♀ intact M2 m 29ThelmaMix 4 y ♀ spayed M3,5 y 30Tom Mix 5 y ♂ neutered L3 y 31Trilly Mix 2 y ♀ spayed M2 y 32Ugo Mix 6 y ♂ intact M6 y Abbreviation: S, small; M, medium; L, large; G, giant.  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 137 of incoming animals and by deciding group composition, housing, and time and occurrence of motor and social activity (inter and intra-species). In the morning, all the dogs are allowed to exercise for nearly one hour in a wide area of more than thousand square meters, which is adjacent to the external pens; the dogs can stay in this area in compatible groups. The dogs submitted to the simplified program of Ethotest-R stayed at the shelter at least 2 months before being tested. Their ages ranged from 5 months (dog #16) to 11 years old (dog #3). 2.2. Establishment of the Evaluation Grid In order to design a scheme for evaluating the behav- ioral components of each dog, we only considered the indicators that are required to a dog for living with hu- mans in a satisfactory companionship; we explored a few dimensions of dogs’ temperament, by referring to the temperament traits described by Jones and Goslin [10]. The schematic version of Ethotest-R is given in Table 2. While Test A was carried out by the Operator 1 only, the sections B,C, and D were designed to analyze three major behavioral traits (fearfulness, aggressiveness, trainability) by two Operators: Operator 1, well known to the dogs and a second Operator, stranger to the dogs, as a control; this second Operator changed from an evaluation to another because he/she became rapidly known after their first entry. In order to differently load the different sections (the items of section C were indeed judged as more critical than B and D), the total scores of the different items were multiplied for a coefficient that was different from one section to another. For the same reason, the coefficient was always higher for Operators 2. The authors supervised the stranger Operators in order to make his/her help consistent with the action to be taken, from time to time. When both the Operators were needed, they worked together (i.e. opening the fence together, enter together, etc). Test A The first screening was focused on the dog aggres- siveness/sociability. This Test was highly selective be- cause it analyzed the aggression component in order to clearly separate the dogs on the basis of a qualitative measurement. According to such hypothesis, the second item A2 has been centered on the component sociability in another qualitative assay. Test A was used to immedi- ately eliminate dogs that failed items 1 and 2 (the total amount of dog’s responses must be two). The Operator 1 only has carried out this first measurement; indeed, if the dogs behaved aggressively or fearfully towards the first Operator, then we assumed that they would behave even worse with unknown people. Test B Test B measured the fearfulness as a tract of the dog temperament. This Test was carried out by the Operator 1, together with the Operator 2 (the latter did not carry out item B3). It analyzed the boldness of the dog to- wards the Operators when they opened the gate of the fence and walked in. It also evaluated the fearful behav- ior of each dog and how they reacted in very unfamiliar places such as the entrance of the building, the corridors, and the veterinary’s ambulatory, surgery, and office. The coefficients used for the evaluations were 1.2 for the familiar person and 1.5 for the stranger. Test C Test C evaluated other dog’s individual differences associated to aggressiveness/submissiveness. For exam- ple, in an open field, the Operator 1 carried out the en- counter with a conspecific for the analysis of inter-dog aggressiveness (C1), followed by the introduction of a novel, unpredictable stimulus (C2), such as blowing a trumpet or producing other unusual noises. Operator 1 also carried out a new item, not previously considered in Ethotest ©, i.e. the hierarchical behavior as regard to food (C3). This investigation was done to determine the dogs’ social position compared with their pen compan- ions (pack), or to the Operator (leader). Conversely, both the Operators 1 and 2 in items C4 and 5 carried out the study on dog suitability with human contact, such as patting, manipulation (which can emphasize a dominant temperament), and jumping on people. In order to pre- dict a successful adoption, the dog’s coefficient score had to be higher than in Test B-namely 1.5 for the Op- erator 1 and 2.0 for the Operator 2. Test D Test D considered the responsiveness to training and play of the dogs by evaluating their skills and their in- terests in learning different commands and behave con- fidently with humans. Dogs were examined twice, by both the Operators, in the external fence and in the lane way that enters the enclosure. Walking on a leash (D1), sit down! (D2), and lie down! (D3) were scored due to their attractiveness on future owners. Playing with the Operators (D4) was chosen to study the disposition of the dog to interact friendly with humans, which is diffi- cult to find in long-term housed animals but expected to be attractive to visitors. The Operators’ coefficient assign- ed for this analysis was the lowest (1.0 and 1.2) because, apart from the advantage to possess these skills, it is not difficult for any equilibrate dog to gain them by education. 2.3. Classification of the Dogs and Cut-Off Value At the end of the tests, the previous program utilized two logical operators (IF and AND: the program is pro- vided as supplementary data t doi: 10.1016/j.applanim. a  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/Openly accessible at 138 Table 2. Ethotest-R. TEST A – Aggressiveness/sociability ID animal age gender size breed item Component Variable Behavior description Scores A1 Aggressiveness towards people the dog snarls or threatens the operator Operator 1 enters the enclosure the dog approaches the operator in a friendly manner 0 1 A2 Sociability/diffidence the dog runs away avoiding the operator’s touch the dog allows the operator to touch him/her 0 1 Totalmust be 2 TEST B – Fearfulness Scores item Component Variable Behavior description Operator 1 Operator 2 B1 Enterprise Attempts of the dog to go out once the gate of the fence is open the dog does not go out the dog goes out by itself the dog goes out only when called 0 1 2 0 1 2 B2 Sociability II When the operator enters the fence the dog: runs away rushes near the operator crouches or goes hesitantly wags the tail and/or licks the operator’s hands 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 B3 Fearfulness to a strange situation The dog is free to entry a new room the dog does not enter the dog enters the room cautiously and/or sniffs continuously the dog enters in a self-assured manner 0 1 2 B4 Confidence towards operators The dog enters a new room with the operator the dog does not enter, except when drawn the dog enters only when called the dog enters together with the operator 0 1 2 0 1 2 B5 Sociability towards unknown people Outdoor: a new person is approaching the dog runs far away the dog goes far/or jumps on people the dog approaches only when called the dog approaches wagging the tail –1 0 1 2 –1 0 1 2 Operator’s coefficient1.2 1.5 Total TEST C – Aggressiveness/submissiveness and jumping Scores item Component Variable Description Operator 1 Operator 2 C1 Aggressiveness toward other dogs In a open field (the exercise area) the dog meets a conspecific, i.e. an unknown dog approaching the fence from the outside the dog runs away or threatens the other dog the dog approaches with hostile, dominant apti- tude the dog approaches with appeasement signals 0 2 1 C2 Fearfulness Introduction of a strong noise stimulus (trumpet) the dog barks or snarls the dog runs away frightened the dog pays attention but does not run away the dog stays calmly –1 0 1 2 While the dog is eating, another dog approaches the bowl the dog snarls and/or attacks the other dog the dog eats voraciously the dog eats quietly or it goes away 0 1 2 C3 Alimentary behavior While the dog is eating, the operator approaches the bowl with her hand the dog snarls the dog eats voracious the dog eats quietly it goes away –1 0 1 2 The operator gently pat the dog the dog runs away or becomes restless and jumps on the operator the dog allows the manipulation and wags its tail 0 1 0 1 C4 Aptitude to be handled Harsher manipulation: the operator restrains the dog with the arms on dog’s back and pushes the dog to the ground the dog rebels or runs away the dog does not react to the domination of the operator 0 1 0 1 C5 Jumping How many time the dog jumps on the operator > 3 < 3 never 0 1 2 0 1 2 Operator’s coefficien 1.5 2 Total  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 139 TEST D – Responsiveness to training and play Scores item Component Variable Description Operator 1 Operator 2 Walking with the operator the dog does not walk on a leash the dog draws the dog draws sometime the dog walks correctly on a leash -1 0 1 2 -1 0 1 2 D1 Walking on a leash Changing direction the dog does not execute the dog executes only when called the dog executes the dog executes with some distractions 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 D2 Sit down! How many times the operator repeats the command the dog does not execute > 5 < 5 once 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 D3 Lie down! How many times the operator repeats the command the dog does not execute > 5 < 5 once 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 With other dogs the dog does not play the dog plays gladly 0 1 D4 Play With the operator (tennis ball, squeezable toys) the dog runs frightened the dog shows no interested the dog plays by himself the dog plays with the operator -1 0 1 2 -1 0 1 2 Operator’s coefficient1 1.2 Total 2005.04.006), which needed the use of a computer to per -form the selection. The logical operators were omitted in this new simplified program; moreover, the scores obtained by each dog in tests B, C, and D were not sub- mitted to an independent evaluation, but they were con- sidered on the whole, and the cut-off necessary value to consider the dog for adoption was “more or equal to 40” , being the final score the resulting total score of the op- erator 1 multiplied for its relative coefficient plus the evaluation of the operators 2 multiplied for its relative coefficient (intra-test confidence). The dogs that did not reach the total score of 40 were considered unsuitable for adoption; the subjects in the range 40-50 were con- sidered fully adoptable dog and in the range more than 50 highly recommended dogs for adoption. 2.4 Adoption and Follow-Up Before adoption the Operator 1 always interviewed the aspiring owners to determine if the dog met their expectation. The questioning was made in an informal way, by asking the adopters about their experience with dog, the time they could have spent with the pet, and their lifestyle and dog’s eventual arrangement. In some cases, the owners were asked to come back to the shelter to socialize with the desired dog; in these cases, a train- ing class was given to them, educating the adopters to a safe and aware relationship with the animal. It consisted of a general instruction about dog needs (behavioral, dietary, and veterinary) and then the explanation of dog postural and vocal signals, the effect of reinforcement and punishment on dog’s learning, walking with a lash, sit!, stay!, and how to avoid house soiling. After the adoptions were successful, to determine if Ethotest-R would predict a consistent behavior of the dogs in the family environment, the necessity of a fol- low-up was considered. To this aim, the Operator 1 car- ried out a home visit two weeks after the adoption (when possible) and always bi-monthly information by phone call for a total of at least five surveys. The follow-up addressed, with a yes/no Test, nasty habits that Chris- tensen and colleagues [3] demonstrated to be unwanted at home, such as: house soiling, jumping up, separa- tion-related behavior, and aggressive behavior of any type (Table 3). We intentionally omitted barking as an unwanted trait because this behavior is often welcomed by Italian dog owners (although not for the neighbor- hood) against criminal offenses both in urban and coun- tryside realities. This interview has been taken by phone call every two months during the first year post-adoption by Operator 1. It focused on a few nasty habits showed by the adopted dog including separation related behavior (3) and ag- gressiveness of any type (4). 3. RESULTS The results of dogs’ evaluation are given in Table 4.  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 140 Table 3. Follow up questionnaire. Nasty habits yes no 1 House soiling 2 Jumping up Object chewing 3 Agitation before being left alone Stranger-directed aggression Owner-directed aggression 4 Dog-directed aggression After being submitted to the Test A, nine dogs out of the original group of 32 were rejected and did not pro- gress to the subsequent items for the insufficient pass mark in Test A; this failure was never ascribable to ag- gressive behavior but to their fearfulness, due to the lack of socialization with humans in the critical period of their life [7]. In the next B, C, and D Tests, being the minimum requested score equal to 40, were rejected four dogs (dogs #1, 14, 16, 31), that presented low score mainly in the socialization items C3 (alimentary behav- ior) and C4 (aptitude to be handled). In the group that we considered to be a sufficient pass mark, (i.e. from 40 to 50) there were only two dogs (dogs #8, 26); then, in a Table 4. Results. Nr. Dog TEST A TEST B TEST C TEST D TOTAL scores Adoptability 3 Biancone 1 / / / 1 Not suitable 4 Bobo 1 / / / 1 “ 11 Grethel 1 / / / 1 “ 12 Hansel 1 / / / 1 “ 18 Louise 1 / / / 1 “ 24 Petra 1 / / / 1 “ 25 Ripa 1 / / / 1 “ 29 Thelma 1 / / / 1 “ 32 Ufo 1 / / / 1 “ 1 Ada 2 3.9 21 2 28.9 “ 16 Leon 2 8.7 15 5 30.7 “ 31 Trilly 2 9.9 21 4 36.9 “ 14 Jamaica 2 15.6 18.5 5 39.6 “ 26 Salvo 2 17.4 19.5 8,2 47.1 Suitable 8 Frank 2 11.1 21 15.4 49.5 “ 28 Snoopy 2 11.4 21.5 15.4 50.4 “ 17 Liz 2 15 21.5 12.6 51.1 “ 13 Jack 2 21 10.2 18.6 51.8 “ 21 Mitzy 2 12.6 21.5 18.4 54.5 “ 2 Bella 2 21.6 16.5 15.4 55.5 “ 10 Gregorio 2 21.6 15 19.2 57.8 “ 20 Manolo 2 19.5 21.5 17.2 60.2 “ 15 Lana 2 21.3 23 14.2 60.5 “ 7 Eva 2 19.5 23 16.2 60.7 “ 27 Secco 2 21.6 24.5 16.4 64.5 “ 6 Didi 2 21 18 24 65 “ 19 Lupizza 2 21 19.5 24 66.5 “ 23 Olguita 2 29.7 18 20.8 70.5 “ 9 Gilda 2 24.3 21 24.8 72.1 “ 5 Bracco 2 25.8 20 24.8 72.6 “ 30 Tom 2 24 23 24 73 “ 22 Nina 2 22.5 22.5 27.4 74.4 “ R esults after dogs’ evaluation with Ethotest-R (ordered per score).  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 141 higher position there were all the other dogs (15 dogs), with scores higher than 50 and even 70, that possessed characteristics of obedience and reliability, and certainly suitable for adoption. After the dogs were judged, twenty-two passed the Test program. Of them, only 12 were adopted, including one dog in a range considered below the cutoff for adoption (dog #16). While in their new family environment, the behavior of those dogs was recorded during the next 12 months. The history of the adopted dogs (alphabetically listed) and the results of the follow-up interviews are summarized in Table 5. No restriction was foreseen for adoption (i.e. experienced or inexperienced owner, presence or absence of children). The decision to commit or not each dog and to train the owners was exclusively related to the expertise and judgment of the authors. A mandatory training before adoption was considered essential for the owners of dogs #7, 13, 16, and 28. In the case of dog #16 the adopter assured that she could have followed the mandatory training class at home with an expert trainer and because of the distance, the home visit was not possible. 4. DISCUSSION This study aimed at giving to adult dog the chance to be successfully housed and at suggesting to shelter managers the possibility to introduce, or at least to con- sult, a qualified dog-expert whose work, differently from the sanitary rule of the veterinarian, can help in the placement of the animals. Being in touch with several shelters in Italy that used a previous program [13] we were solicited to simplify the Test, making it more suitable for a day-by-day selec- tion of shelter dogs. In this study, any dog was known and selected by a qualified Operator, whose expertise was in the field of animal welfare, training, and behav- ioral education of both owners and dogs. The Ethotest-R program showed a better feasibility than the previous Test: in fact, this version could be daily accomplished in the shelter environment, provided that the dog-expert Operators could dispose of external and unknown places where to carry out all the items. We did not repeat the Test to analyze the consistence of dogs’ behavior: we found that, given that the animal behavior and human interaction is affected by many conditions, the repetition of the Test a few months later could have been very dif- ficult and useless for our purpose. The results were in- deed validated by asking the owners about dog’s behav- ior in the new environment; the follow-up is in fact a useful tool to understand the evolution of the animal’s personality [22]. Differently from other authors [3], in our study the follow-up results demonstrated that Ethotest-R could be evaluated as a suitable adoption Test; although only 32 dogs were evaluated (all the dogs housed in that shelter), the sensitivity of the Test (the proportion of true positives that are correctly identified [23]) was 100%, i.e. every adopted dog was reported as behaving well by their owners that responded to the Op- erator 1 interviews. The follow-up focused on items that have been demonstrated to be the primary reason for returning a dog to a shelter, i.e. behavioral problems Table 5. Follow-up of twelve dogs (ordered by dogs’ ID number) one-year post-adoption. ID n. Dog’s name Sex Scores Adopter’s Family Presence of childrenPrevious dog/s ownership Dog housingFollow up 2 Bella F s 55.5 Woman with a dog- Yes Home N 5 Bracco M 72.6 N 9 Gilda F s 72.1 Young man - Yes Garden N 7 Eva F s 60.7 Separated woman 2 teenagers No Home N 8 Frank M 49.5 Family - No Home N 13 Jack § M n 51.8 Man - Yes Home N 16 Leon * M 30.7 Young woman - No Home N 17 Liz F 51.1 Family 2 No Home N 19 Lupizza F s 66.5 Family - Yes Garden N 23 Olguita F s 70.5 Family 1 Yes Home N 26 Salvo M 47.1 Family 3 Yes Home N 28 Snoopy F s 50.4 Family 2 No Home N The table represents the dogs adopted from the ASL 04 shelter after their evaluation. It underlines sex, total score obtained, adopter’s family situation and ex- perience with dogs, and home/garden arrangement. In the last columns there are the results of the interviews taken during one-year of ownership in relation to dog’s nasty habits (house soiling, jumping up, separation anxiety, and aggression). Sex: F = female; M = male; s = spayed; n= neutered. Follow up: N= negative for all the nasty habits. §confiscated; *relinquished.  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 142 [2,5,6,14,19,26]. No noisy habits were registered during one-year follow-up, first of all the aggressive behavior. Despite the professional expertise, two dogs (i.e., #13 and 16) were not efficaciously paired with their owners. The first was victim of mistreatments and confiscated, the latter was a predictable case of relinquishment, being a dog not suitable for adoption (total score below the cutoff value); he left the shelter just before his owner completed the mandatory training . Dog #13, a dog that could have been forced to become aggressive towards humans by the bad treatment he suffered, did not show any sign of aggression, rather a form of depression in the new situation. Although it has been demonstrated that the ability to execute basal commands significantly red- uces the likelihood of relinquishment [5,14,16,21,24,25], promoting a “successful human-dog bond”, this was not the fate of dog #13. Apart from these cases, from our study it seems that people were more attracted by educated dogs that is, in conclusion, that dog’s behavior is more important to a potential adopter than the dog’s physical appearance. Every positively judged dog fulfilled the owner’s expec- tation after adoption: there was no difference found be- tween entire or neutered pets, and also the factor of gen- der was not found significant [4,16,18]. In our trial, not even inexperienced (first-time) owners had problems with their dog (e.g. dog #7) despite our knowing that this situation could present a risk. In our study, some families had children or teenagers and, even if children are often victims of aggressive dog behavior associated with bit- ing [1,11], not one of the adopted dog showed aggressive behavior towards humans and particularly towards chil- dren. In other studies male dogs have been ranked as more dangerous than females by their owners [8], but this occurrence was denied by our results as well as by Kobelt et al. [12]. We believe that the caregiver’s expertise (in this case, Operator 1) can make the difference between a success- ful adoption or not, and that the adopter’s training pre-ownership is mandatory. Moreover, if the worries about dog aggression towards humans and particularly children make sometimes difficult for people the appro- priate breed and age choice, the possibility to talk with a professional expert can drive away doubts and fears, for example by overcoming the damaging concept that a fully developed dog will not be suitable for adoption as much that the behavior that a puppy will exhibit at the adult age is unpredictable. It appears however actually clear that there is a constant, lively demand of reliable methods to easily and successfully pair humans and dogs, for the need to adopt consistently behaving dogs. The Ethotest-R method could be a good example of dog se- lection, provided that the Operator selecting and ranking the animals is an authoritative expert of theoretical and practical management of dogs. This professional rule could be equivalent to that of a veterinary technician or to a companion animals’ ethologist. These individuals should absolutely know the animals they want to test, i.e. they could not be people employed for food administra- tion and pen cleaning. They also need to know the theo- retical and practical aspects of inter-dog and dog-human interaction. In our case, the Operator was a doctor in Animal Welfare and Protection, with a three-year degree that is consistent with the veterinary technician role of other European and American countries. Obviously, the possibility to have an expert integrated in the shelter staff can shorten Ethotest-R since the uselessness to carry out the Test A. 5. CONCLUSIONS The prejudice existing against mature dogs makes the adoption from shelters more difficult. How to persuade people to choose an unattractive, sometimes depressed, adult sheltered dog? What strategy could tip the scales in favor of a new trend in adoptions? How to offer to those unwanted dog the possibility to a better life, far from these prisons? We think that different strategies should be undertaken: to enact regional laws forcing the owners to report the birth of puppies from their bitches: in our country, the relinquishment of dogs adopted from shelter is not as frequent as expected. Any dog adopted from a shelter can, in fact, be traced by his/her microchips. On the contrary, it is extremely difficult to afford the problem of abandoned dogs born from family’s bitches; in some cases, they are abandoned far away or given as a present. Frequently puppies are appre- ciated until they became a demanding task but, when they no longer suit their owners’ needs, they are re- linquished without any remorse; to give those shelter dogs a challenging, interesting environment to live; we know, indeed, how the dev- astating, depressing environment, in which aban- doned or stray dogs are forced to live can perma- nently invalidate their temperament [25], when it lacks the appropriate physical, psychological and human enrichment; to give sheltered dogs an economical value, which can prevent the recurrence to the shelter; (a no-cost dog can be easily replaced by other no-cost dogs); to accomplish a basal training by a qualified behav- ioral caretaker that could help the dog to become more attractive or, at least, to dispose of a easy, pratical Test to perform a safe selection. Moreover, it should be stressed that customer satisfac- tion relies not only on a distant Test; the human factor  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 143 (knowledge and practice) is always behind it and it seems to have become more and more indispensable to efficaciously pair humans with dogs. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Authors wish to thank the Veterinary Department of L’Aquila ASL 04 for the logistic support, Prof. Francesca Rosati (University of Teramo) for editing of this paper and Dr. Nicola Bernabò for his com- ments. The work was supported by the University of Teramo, financial support ex 60% 2009. REFERENCES [1] American Veterinary Medical Association Task Force on Canine Aggression and Human-Canine Interaction. (2001) A community approach to dog bite prevention. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association, 218, 1732- 1749. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.218.1732 [2] Bollen, K. S. and Horowitz, J. (2008) Behavioral evalua- tion and demographic information in the assessment of aggressiveness in shelter dogs. Applied Animal Behav- iour Science, 11 2, 120-135. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2007.07.007 [3] Christensen, E., Scarlett, J., Campagna, M. and Houpt, K.A. (2007) Aggressive behavior in adopted dogs that passed a temperament test. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 106, 85-95. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2006.07.002 [4] Clevenger, J. and Kass, P. H. (2003) Determinants of adoption and euthanasia of shelter dogs spayed or neu- tered in the University of California veterinary students surgery program compared to other shelter dogs. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 30, 372-378. doi:10.3138/jvme.30.4.372 [5] Diesel, G., Pfeiffer, D.U. and Brodbelt, D. (2006) Factors affecting the success of rehoming dogs in the UK in 2005. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 84, 228-241. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.12.004 [6] Fatjó, J., Ruiz-de-la-Torre, J.L. and Manteca, X. (2006) The epidemiology of behavioral problems in dogs and cats: A survey of veterinary practitioners. Animal Welfare, 15, 179-185. [7] Freedman, D.J., King, J.A. and Elliot, O. (1961) Critical period in the social development of dogs. Science, 133, 1016-1017. doi:10.1126/science.133.3457.1016 [8] Guy, N.C., Luescher, A.U., Dohoo, S.E., Spangler, E., Miller, J.B., Dohoo, I.R. and Bate, L.A. (2001) Demo- graphic and aggressive characteristics of dogs in a gen- eral veterinary caseload. Animal Behaviour Science 74, 2-15. [9] Hsu, Y. and Serpell, J. A. (2003) Development and vali- dation of a questionnaire for measuring behavior and temperament traits in pet dogs. Journal of American Vet- erinary Medical Association, 23, 1293-1300. doi:10.2460/javma.2003.223.1293 [10] Jones, A.C. and Goslin, S.D. (2005) Temperament and personality in dogs (Canis familiaris): A review and evaluation of past research. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 95, 1-53. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.04.008 [11] Kahn, A., Bauche, P. and Lamoureux, J. (2003) Child victims of dog bites treated in emergency departments: A prospective survey. European Journal of Pediatrics, 162, 254-258. [12] Kobelt, A.J., Hemsworth, P.H., Barnett, J.L. and Cole- man, G.J. (2003) A survey of dog ownership in suburban Australia—conditions and behaviour problems. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 82, 137-148. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00062-5 [13] Lucidi, P., Bernabò, N., Panunzi, M., Dalla Villa, P. and Mattioli, M. (2005) Ethotest: A new model to identify (shelter) dogs’ skills as service animals or adoptable pets. Applied Anima l Behaviour Science, 95, 103-122. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.04.006 [14] Luescher, A.U. and Medlock, R.T. (2009) The effects of training and environmental alterations on adoption suc- cess of shelter dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 117, 63-68. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2008.11.001 [15] Marston, L. C. and Bennet, P. C. (2003) Renforcing the bond-towards successful canine adoption. Applied Ani- mal Behaviour Science, 83, 227-245. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00135-7 [16] Marston, L. C., Bennet, P. C. and Coleman, G. J. (2005) What happens to shelter dogs? An analysis of data for 1 year from three australian shelters. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 7, 27-47. doi:10.1207/s15327604jaws0701_2 [17] Mondelli, F., Prato Previde, E., Verga, M., Levi, D., Magistrelli, S. and Valsecchi, P. (2004) The bond that never developed: Adoption and relinquishment of dogs in a rescue shelter. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Sci- ence, 7, 253-266. doi:10.1207/s15327604jaws0704_3 [18] Patronek, G. J., Glickman, L. T. and Moyer, M. R. (1995) Population dynamics and the risk of euthanasia for dogs in an animal shelter. Anthrozoos, 1, 31-43. doi:10.2752/089279395787156455 [19] Segurson, S. A., Serpell, J. A. and Hart, B. L. (2005) Evaluation of a behavioral assessment questionnaire for use in the characterization of behavioral problems of dogs relinquished to animal shelters. Journal of Ameri- can Veterinary Medical Association, 227, 1755-1761. doi:10.2460/javma.2005.227.1755 [20] Selby, L.A., Rhoades, J.D., Hewett, J.E. and Irvin, J.A. (1979) A survey of attitude towards responsible pet own- ership. Public Health Report, 94, 380-386. [21] Shore, E.R. (2005) Returning a recently adopted com- panion animal: Adopter reasons for and reactions to the failed adoption experience. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 8, 187-198. doi:10.1207/s15327604jaws0803_3 [22] Svartberg, K. (2005) A comparison of behavior in test and in everyday life: Evidence of three consistent bold- ness-related personality traits in dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 91, 103-128. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2004.08.030 [23] Taylor, K.D. and Mills, D.S. (2006) The development and assessment of temperament tests for adult companion dogs. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 1, 94-108. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2006.09.002 [24] Thorn, J., Templeton, K., Van Winkle, M. and Castillo, R. (2006) Conditioning shelter dogs to sit. Journal of Ap- plied Animal We lfare Science, 9, 25-39. doi:10.1207/s15327604jaws0901_3  M. Sticco et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 135-144 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/Openly accessible at 144 [25] Tuber, D. S., Miller, D. D., Caris, K. A., Halter, R., Lin- den F. and Hennessy, M. B. (1999) Dogs in animal shel- ters: Problems, suggestions, and needed expertise. Psy- chological Science, 10, 379-386. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00173 [26] Wells, D. L. and Hepper, P. G. (2000) Prevalence of be- havior problems reported by owners of dogs purchased from an animal rescue shelter. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 69, 55-65. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(00)00118-0

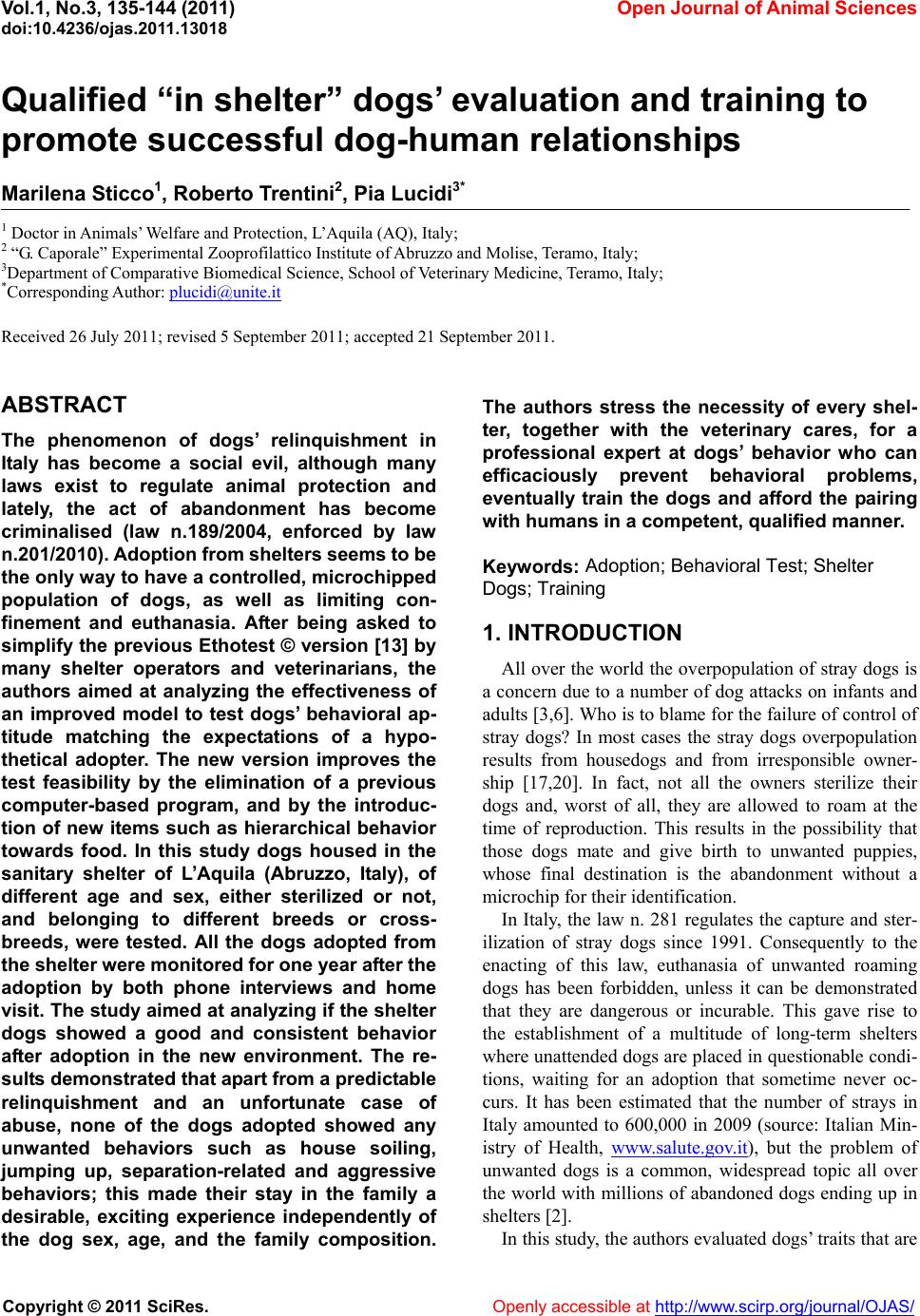

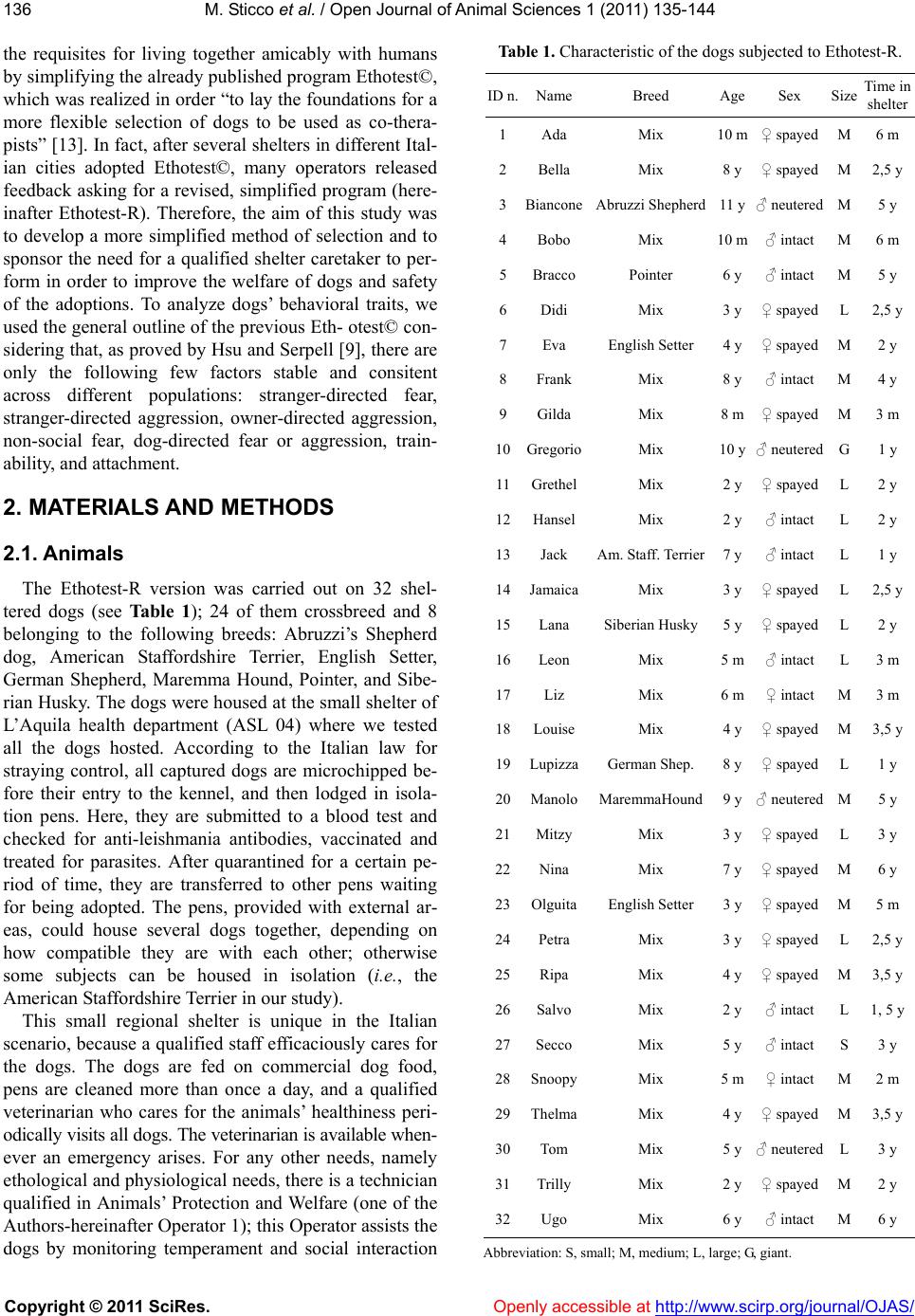

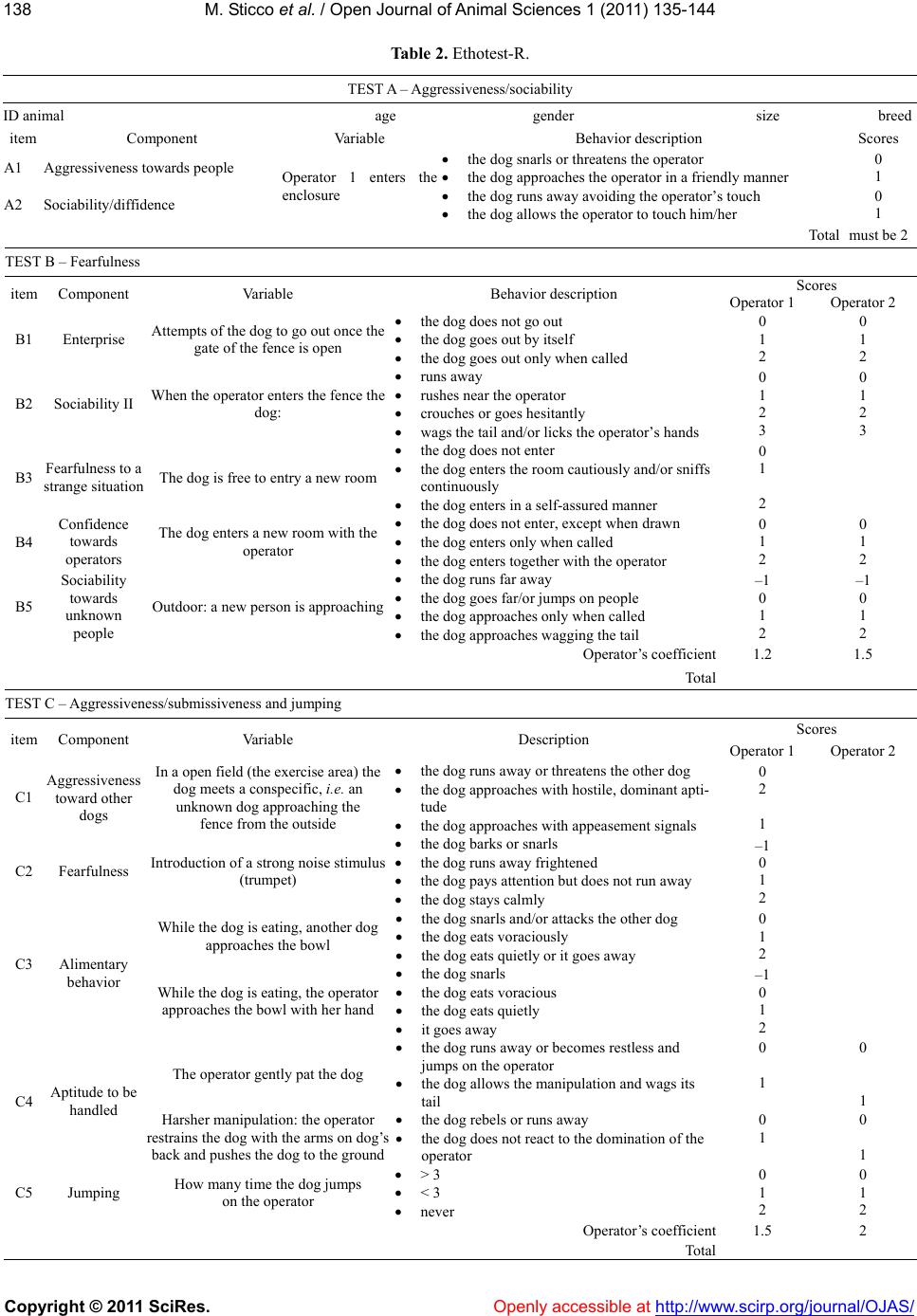

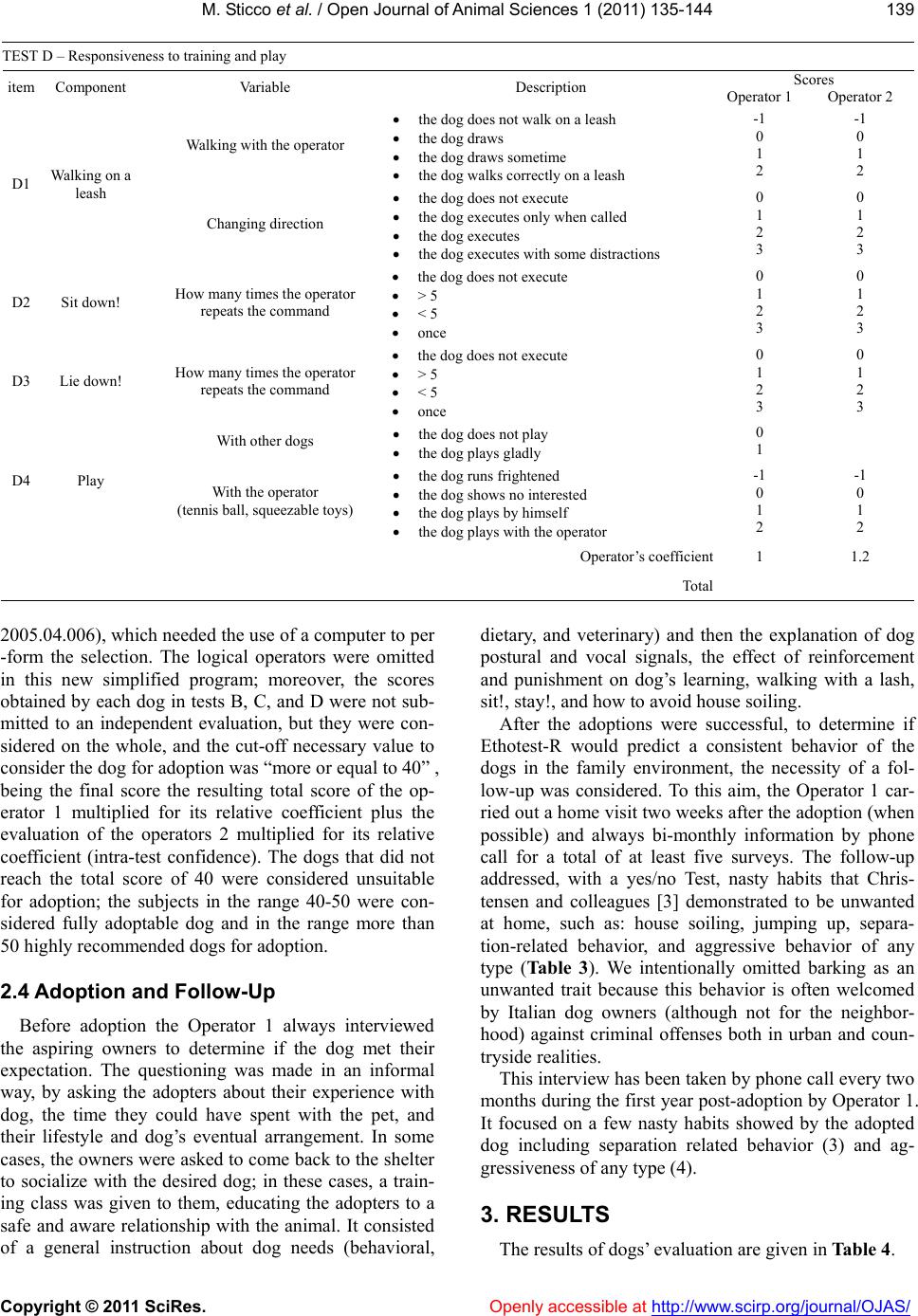

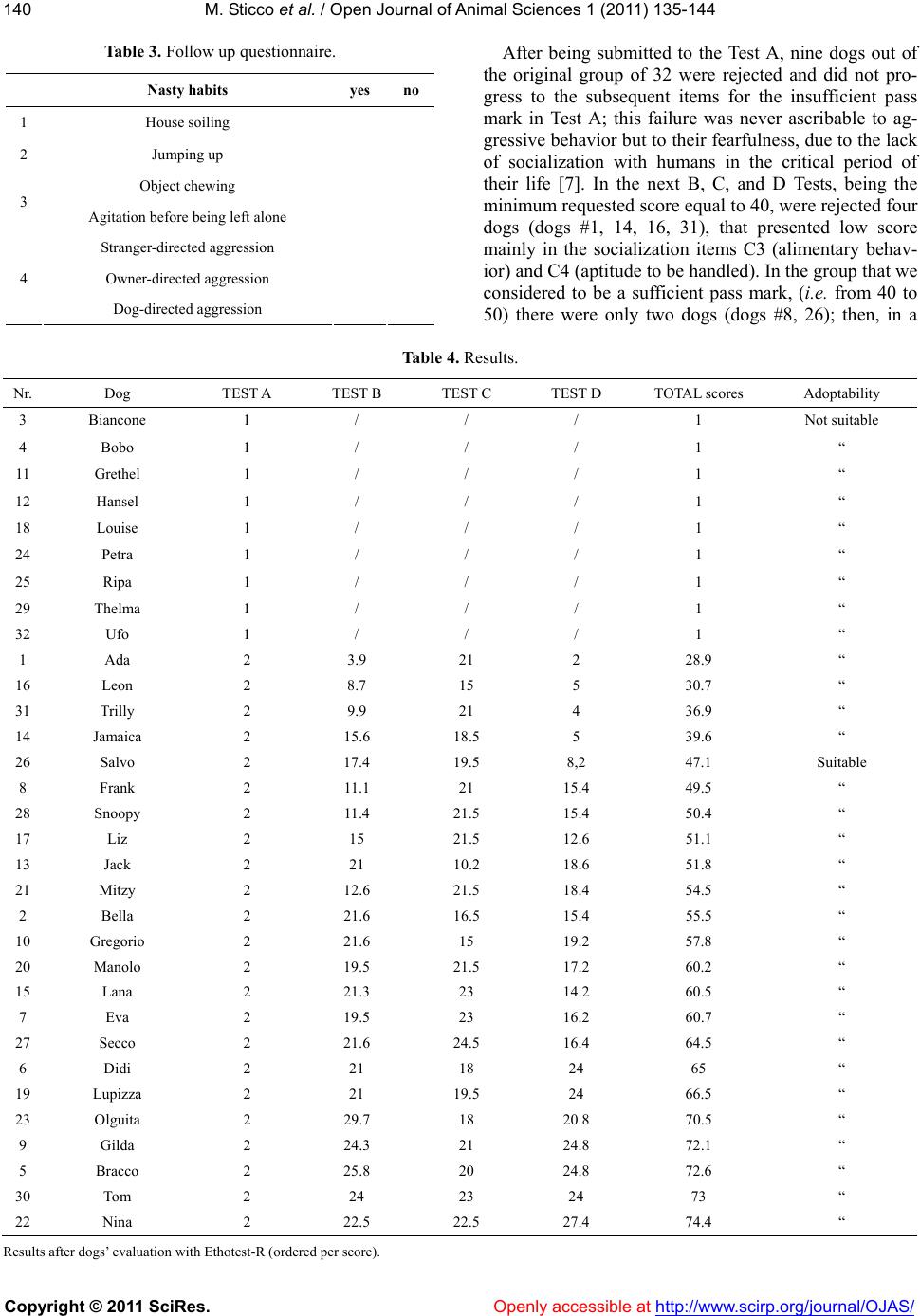

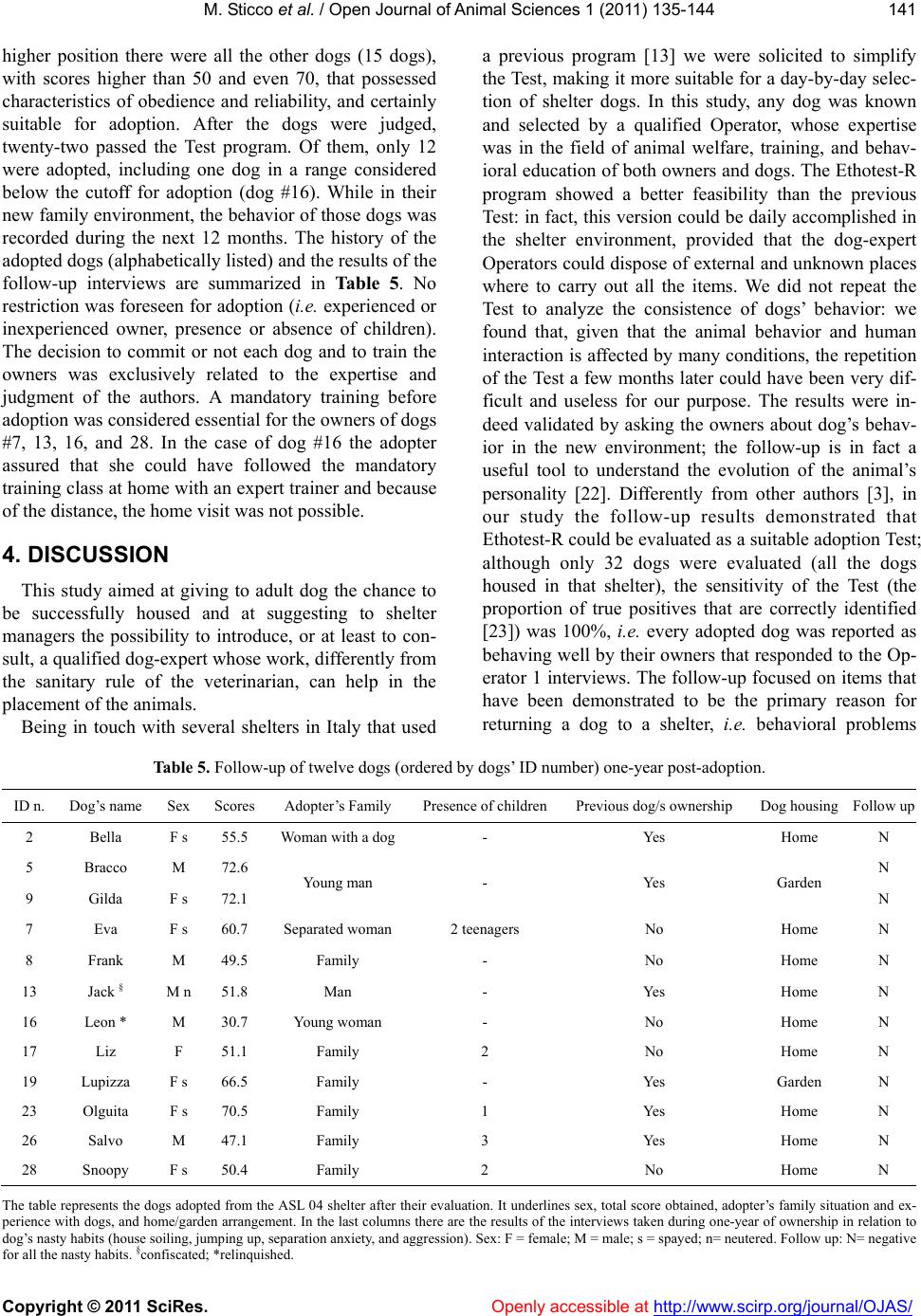

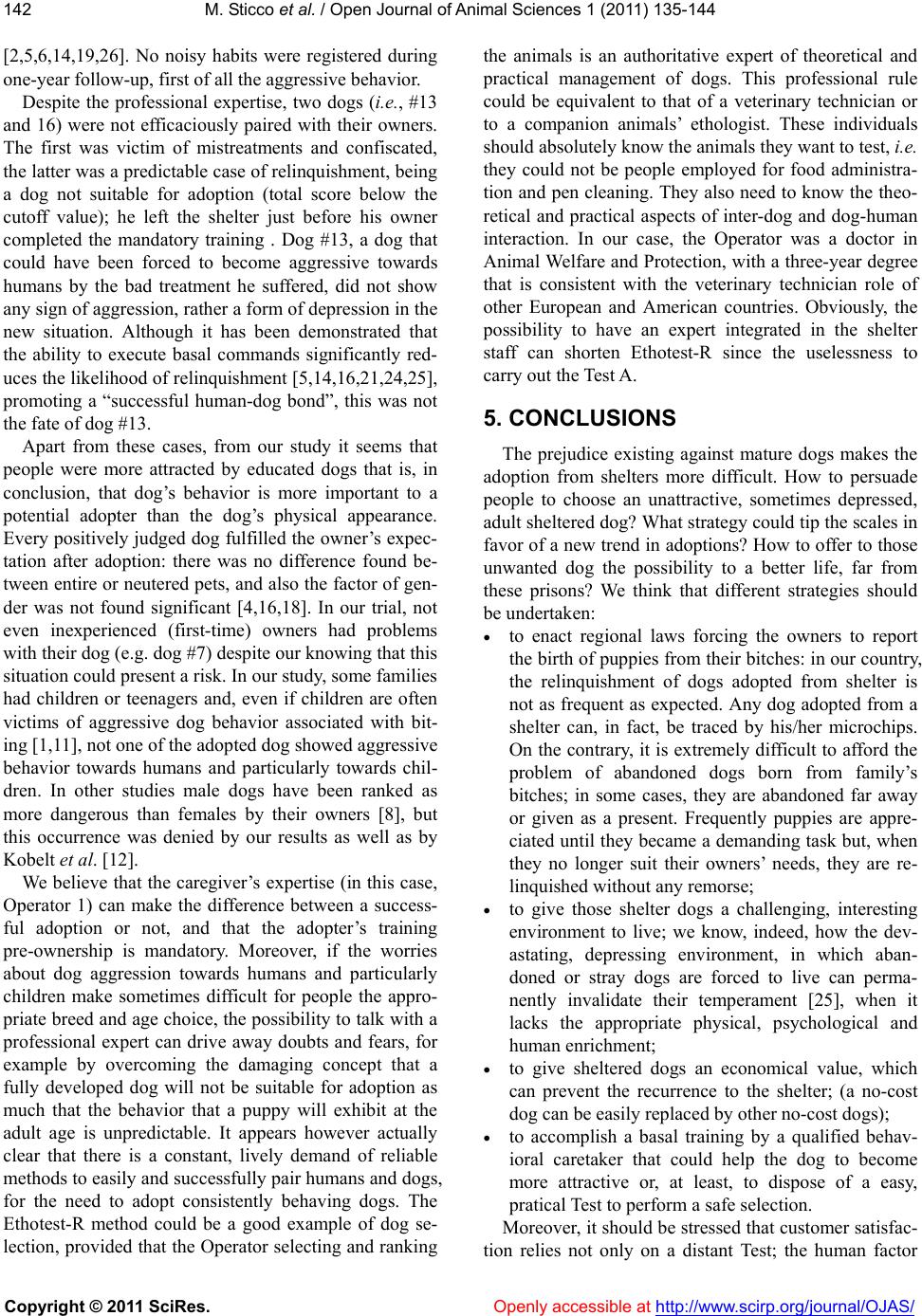

|