Vol.1, No.3, 128-134 (2011) doi:10.4236/ojas.201 1.13017 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ Open J ournal of Animal Science s Informed consent in veterinary medicine: legal and medical perspectives in Italy Annamaria Passantino, Valeria Quartarone, Maria Russo Department of Veterinary Public Health, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Messina, Polo Universitario Annunziata, Messina, Italy; passanna@unime.it Received 5 July 2011; revised 20 August 2011; accepted 3 September 2011. ABSTRACT During the last four decades the doctrine of in- formed consent (IC) has become a legal stan- dard and an essential component of ethical guidelines in medicine, due to its relevance for basic human rights such as autonomy and re- spect of dignity. Over the last few years, this legal formula has gained importance in veteri- nary medicine, thereby influencing the everyday activities of the veterinary practitioners. This paper briefly describes the ethical and legal background of IC in Italy and examines how it relates to the practice of veterinary medicine, considering the change in social sensibility to- wards animals. It also outlines the discussion that should take place between Veterinarian and client before a planned procedure. Keywords: Informed Consent; Veterinary Medicine; Professional Duty; Law; Ethics; Veterinarian-Cli ent Relationship; Animal 1. INTRODUCTION In recent years, patients’ consent to medical treatment has particularly attracted the attention of legal doctrine and law, becoming the object of continual research and various interpretations and becoming so relevant as to gain independence from medical duty as a whole. From a paternalistic perspective, when the physician was the sole depository of medical secrets and therefore the only one who could make decisions, physicians and patients have moved on to a new relationship as col- laborating peers [1]. The principle of informed consent (IC), in fact, re- flects the concept of autonomy and self-determination [2] of a person requiring and requesting specific medical and/or surgical intervention. The theory of autonomy is defined as self-governance or self-rule, a capacity of people to reflect and choose, and freedom to express individual aspirations and preferences [3]. Such a justification of IC also lies with the fact that, in most of Europe and beyond it [4], physicians’ ethical codes see the duty to ask for IC as an expression of pro- fessional correctness itself [5]. Like physicians, veterinarian have concerns about client confidentiality, and are troubled by ethical con- flicts that arise when the interests of patients (chil- dren/animals) and clients (parents/owners) diverge. How- ever, since animals are typically treated legally as a form of property, the ethical and practical problems for vet- erinarian have substantive differences from those faced by physicians. From a legal perspective, the confidential relationship presumed between physicians and patients does not always explicitly apply to veterinarian and their clients. Nevertheless there are circumstances where confiden- tiality requirements are explicitly waived to protect pub- lic or animal health. For example, the Italian Principles of Veterinary Ethics indicate that a doctor of veterinary medicine has an obligation to protect the privacy of cli- ents, but make an exception if a veterinarian is required by law to reveal confidential information, or if it be- comes necessary to protect the health and welfare of an individual, animals, and/or others whose health and welfare may be endangered. Relating to IC, veterinarians have a rather unique po- sition, because the law does not oblige them to have the patient-owner sign a document like in human medicine [6]. A veterinarian’s only obligation is of a moral kind. 2. BASIS OF INFORMED CONSENT IC is the process of obtaining the permission of the patient to have an opportunity to decide about his/her health care. This definition originates from the legal and ethical right of the patient to retain autonomy and from the ethical duty of the physician to involve the patient in health care decisions. A professional and his/her client are bound by a con-  A. Passantino et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 128-134 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 129 tract: the latter applies to the first for a professional ser- vice and, from the time the former accepts, he/she is obliged to the client as to the use of certain means, not as to the outcome. The risk of missing the target will lie with the client. Along with this main obligation, the professional is bound to fulfill secondary obligations. Italian law on contracts (article 1175 of the Civil Code) enforces the obligation to behave “according to the rules of correct- ness”: a specific application of this principle is the pro- fessional’s “duty to inform”. Actually, clients of nearly all professions, or better creditors of professional services, must, to a certain ex- tent, make choices that involve weighing costs and benefits, which may be complex and hard to understand. To make decisions, they have to rely on their general learning and on correct information from the profess- sional. Especially in the medical profession, IC cannot be done without, but to this day it is hard to define, stating its limits and range, pointing out the multifarious situa- tions in which it becomes relevant [7]. A conscious person, in full possession of his/her men- tal faculties, will not have to passively undergo any medical treatment (diagnostic tests, therapy, surgery, etc.); this concept derives from the constitutional prince- ple of the inviolability of personal freedom and the right to health that produce the legal claim to self-determina- tion and the refusal of all illegitimate interference. In fact, in according to articles 13 and 32 of our Con- stitution, the valid consent of the person in question is necessary, and he/she shall give it only after receiving appropriate information and sufficient elements to evaluate the treatment he/she will have to undergo and the consequent hypothetical risks. Clearly, IC involves the patient’s participation, awareness, information, freedom to choose and decide. Consent is valid after previous complete information: a physician is obliged to supply the indispensable ele- ments to inform the patient sufficiently about the kind of treatment, the therapeutic alternatives, the aims, the chances of success, the risks and side effects [8]. IC includes not only the important and fundamental autonomy of the patient to decide, but also the essential objective element, that is, information. The expression IC has simply been transposed in Italian and approxi- mately translated in an ambiguous fashion into “con senso informato” when really it should be referred to as “informazione per il consenso” (“information for con- sensus”) not only to respect the concept but, surely, for a more correct deciphering and a more precise interpreta- tion related to the numerous concepts it presupposes and implies. Information and consent may be viewed as the two sides of the same coin; in fact Mallardi (2005) writes that “ […] on the one ha nd, having obtained con- sent, following correct and sincere information inter- preted and deciphered as an important phase and an essential indicator of correct, scrupulous medico-pro- fessional procedure and, on the other, the consensus itself conceived as a duty aiming at the maximum respect of the rights to self-determination, independence and autonomy of the patient”. The jurisprudential and doctrinal debate, arising in re- lation to the IC, must not turn it into just another bu- reaucratic performance or a conflict in the physic- cian-patient relationship, or reduce it to a formality, for the physician to protect himself against a potential law- suit, but must be seen as a moment in the fundamental therapeutic alliance between patient and physician, which alone allows them to face a disease correctly. The ratio in the request for IC must, therefore, be identified in the determination to promote autonomous health decisions, which has been left aside since the time of Hyppocrate’s philosophy, which acknowledged that physicians had the duty and right to tell nothing to the patient about his/her health conditions and the health treatments he/she was undergoing ([…] reveal nothing to the patient about any event to come […]), both to avoid “extreme measures” from the patient and to guarantee the physician’s prestige and authority [9,10]. 3. INFORMED CONSENT IN ITALY IC in a veterinarian-client relationship (VCR) is vastly different from IC in a medical doctor-adult human pa- tient relationship; where in a veterinarian-client-patient relationship (VCPR), the patient is not capable of mak- ing a decision for him or herself. By contrast, in a rela- tionship between a medical doctor and an adult human patient, the patient can make the decision him or herself. Veterinarian-client IC is not based on the principle of individual autonomy, since it expresses the subject’s self-determination, which the animal species is not en- dowed with. The IC paradigm for human beings is in fact practi- cally inseparable from its reference to autonomous moral subjects [2,11]. Since veterinary practice deals with non-autonomous moral patients, the reference to consent has a different meaning. In veterinary medicine, where no rule of law obliges the veterinarian to obtain IC mak- ing it a sanitary service (with the exception of Ministe- rial Circular no. 14 of 25 September 1996 on Good prac- tices of Clinical Experimentation of veterinary drugs on animals), and informing the client-owner is a duty con- nected with Good Practice (Code of Good Veterinary Practice of the Federation of Veterinarian of Europe, approved by the Federazione Nazionale degli Ordini  A. Passantino et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 128-134 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 130 Veterinari Italiani [FNOVI], Jan.29, 2005) and the Italian Ethical Code of rights and responsibilities of veterinary- ian, and on the other hand—justified by the ever-in- creasing technicalities and specialization of the veteri- nary profession—represents a form of certified qualifica- tion of the performances offered by the Veterinarian. In fact, article 29 of the Italian Ethical Code (Duty to inform and informed consent in veterinary practice) states that “The Vet, on undertaking contractual respon- sibilities, is bound to inform his client clearly on the clinical situation and the therapeutic solutions. The Vet mu st inform exactly o n the risks, the costs and benefits of the different and alternative diagnostic and therapeutic routes, as well the predictable consequences of the eventual decisions. On informing the client, the Vet will ha ve to consid er h is/her degree of understanding, in order to allow them to give full approval to the diag- nostic-therapeutic proposals. Any additional information required by the customer must be satisfied. A Vet must also answer all investigations on preven- tion matters from the public at large. The Vet is bound to inform his/her client on the pre- dictable suffering and pain of their animal and on the presuma ble du rat i o n of the professional operati on. It is the Vet’s duty to communica te to a client the need to perform particular actions, in order to avoid suffering, pain or prolonged illness in the patient animal”. It being understood that consent is necessary, we must say that the choice of the treatment lies with the Veteri- narian, because, for his/her professional skills, technical and scientific knowledge of medicine, he/she stands on a higher level than the owner of the animal. Once the treatment has been chosen, the veterinarian must propose it to the client, who might not accept it. In this case, the veterinarian is free of any professional obligation and is not obliged to carry out any treatments that the client may considers suitable, but which are against the physic- cian’s “science and conscience”. Conversely, if the veterinarian thinks that more than one treatment is suitable, the ultimate choice lies with the client who has ultimate responsibility for the animal and for decisions about its welfare. In veterinary medicine, getting this IC typically means the veterinarian explains both the risks and benefits as- sociated with a specific medical or surgical intervention. IC is an important concept in the VCPR because it is part of what defines the boundaries of that relationship. In addition to defining how the veterinarian and the cli- ent together make decisions regarding the care of the patient, IC also defines how the veterinarian deals with the client. If the veterinarian does not give the client enough information to allow the client to give IC, the veterinarian has failed to uphold one of his or her duties to the client and to the patient. IC is rooted in the idea of protecting both the client and the veterinarian. 4. OBTAINING INFORMED CONSENT Obtaining IC from clients is a crucial element of ethi- cal and professional communication in veterinary medi- cine. In non-emergencies, obtaining IC requires the vet- erinarian to discuss with the client the clinical issues, the alternatives to the proposed diagnostic or therapeutic intervention (in addition to the benefits and risks of each option), and the possible adverse effects and long-term care associated with each option [12]. In addition to the standard “clinical” elements of this conversation, the veterinarian should attempt to assess the client’s prefer- ences for and understanding of the choices before him or her. Having first said that the quality and quantity of the information supplied by the Veterinarian to his/her client does not depend on its eventually being formalized or not, it is however highly important, if one thinks that incorrect information might be cited in a lawsuit. However, there are different evaluations of the “de- gree” of information to be offered to the client-owner. Information must therefore be as complete as possible, true and objective. In particular, it must comply with the following prin- ciples: Information must be proportional to the importance of the procedure or treatment method; Information, though complete, must be limited to the elements that a client can understand; Information, though objective, must leave aside purely scientific aspects. More specifically, the entries in a clear and complete IC form will include diagnosis, therapy (medical and/or surgical), etc., as shown in Table 1. Those suggestions, however, do not limit the possibil- ity to introduce further data that might be necessary in specific cases. One aspect, which the veterinarian must take into consideration before informing his/her client of the costs-benefits of a treatment or procedure he/she deems necessary for an animal to undergo is the duty to inquire about the destination of the animal. So, for example, when the veterinarian diagnoses pyometra in a bitch, on advising surgical hysterectomy, he/she will have to inform the owner that such a treat- ment, though promising good chances of recovery, will compromise her reproductive function forever. In the absence of such information, the owner might report the veterinarian for its incompleteness, in case he/she could prove that a different decision would have been taken on  A. Passantino et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 128-134 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 131 Table 1. Kind of information offered to the client-owner5. Diagnosis Description of the diagnostic course Benefits Risks Prices Moral and other implications of the course chosen Diagnostic hypothesis, if any, and differential diagnosis Therapy (medical or surgical) Description of the recommended surgery and reasons for its choice Benefits Risks Materials used Complications and consequences of the therapeutic procedure from the point of view of both man and animal Prices Therapeutic alternatives or no operation Difficulties in dealing with the patient or convalescent Ethical or other implications of the therapeutic course Unexpected events taking place during the therapeutic deed, where it is impossible to communicate with owner Anaesthesia Proposed or alternative anaesthesia Preliminary tests Benefits Risks Costs Ethical implication the basis of complete and correct information. A practical aspect of the IC form relates to the possi- bility of including the costs of treatment among its en- tries. Although news about the costs make information complete, they should be kept separate from the rest, because, for their purely economic value, they represent a proforma invoice on the veterinary service; on the con- trary, the aim of IC is informing the client of the costs and benefits of a certain service. As regards the forms the expression of consent can take, unlike in human medicine, where consent must be given in writing, in veterinary medicine the written form is not obligatory, although there is a practical tendency to identify IC with a written form. Having said this much, we can distinguish between various ways to express consent: 1) Tacit or implicit consent, when the subject’s will is inferred from his/her behavior, not from an explicit statement. 2) Explicit consent, when someone’s will is expressed, either in writing or orally. There being freedom as to form, we can usefully con- sider whether it is advisable for a Veterinarian to use written forms. Obtaining an IC form for any service a veterinarian may perform is surely unthinkable. Transferring what is the custom in human medicine, we can distinguish be- tween: a) routine activities (e.g. vaccination), to which im- plicit or oral consent is sufficient; b) extra-routine activities, or those which may pro- voke irreversible consequences (i.e. euthanasia, castra- tion, caudectomy, horn-abrasion, amputation of a leg) or a risk (surgery), for which IC in writing is advisable, though not necessary. In box 1 we propose a facsimile. This facsimile consent form includes the name and address of the client (owner) and the name, species, breed, sex, and date of birth of the patient. Additionally, it should include a clause indicating that the person signing the form is the legal owner of the patient and has the authority to consent to treatment. Following that clause, another clause has spaces to iden- tify the veterinarian, the veterinary hospital or office, and the treatment(s) being administered to the patient. Next is a clause indicating that the client has been in- formed of the possible risks and complications of the treatment, and indicating that the client is aware that unforeseen problems may arise which require further treatment. Then, there is a clause which authorizes the use of anaesthesia or pain medications as needed before or after the procedure(s). After that, a sentence indicates that the client is aware that other personnel may be re- quired in order to assist the veterinarian. Finally, the signature lines are provided for the client and/or a person acting as an agent on behalf of the client. When the client signs the document, he/she declares that he/she has understood the risks and benefits. By giving IC to a procedure or treatment, it is assumed that the client both read and understood all of the terms in the statement. Once IC has been given, the patient-animal may be treated according to the conditions listed within the statement. In the case of oral consent veterinary professionals responsible for communicating with clients must be sen- sitive to cultural differences for it to be satisfactory. They should be alert to the possibility that individual words may carry distinct meanings in different regional dialects of the same language. Further, there is the po- tential for two-way prejudice (veterinarian versus client and client versus veterinarian) based on race, gender, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, religious or spiritual beliefs, social status, economic status, or literacy level. Conflict in these situations is nearly always communi- cated nonverbally; thus, veterinarians should be vigilant in observing any evidence of client discomfort or the possibility of being misunderstood. The emergency setting can place several constraints on the procedure of obtaining IC. In emergency situa- tions, where there is often insufficient time to establish rapport with the client and/or easily to explain the com-  A. Passantino et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 128-134 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 132 plicated medical condition of the animal, the veterinarian should be truthful, exercising care and flexibility. In settings involving the communication of bad news, especially when there is no appropriate biomedical re- sponse, the fundamental skill needed is empathy [13,14]. In fact, expression of empathy, if appropriate, can en- courage the client to maintain realistic hope about the bad news. The veterinarian, like the trained medical professional, provides only the information that is perceived to be required and asks for the client’s trust and approval of a medical plan that is outlined as quickly as possible. For example, the veterinarian may briefly inform the client on the life-saving therapies, the probable long-term out- come from the medical condition, the cost associated with the immediate medical plan, and in extreme cases (severe mitral valve endocardiosis, metastatic mammary carcinoma, etc.) the option of euthanasia. Fallowfield & Jenkins (2004) [15] suggest that the way in which bad news is delivered can have a signifi- cant impact on the VCPR, decrease the stress for the deliverer of bad news, and improve several important outcomes from the receiver’s perspective. 5. INFORMED CONSENT AND DUTY A Veterinarian’s duty regarding IC is two-fold. A Vet- erinarian has a duty to inform the client and obtain the client’s consent. The legal approach to establishing this duty is pragmatic. Although the client has the right to refuse, it is recognized that the Veterinarian possesses more information and, as a consequence, more power to control the circumstances under which the two parties meet. In addition, the Veterinarian has a duty to respect and promote the animal-patient’s best interest. As such, it is the Veterinarian who is held to a higher standard and thus a greater duty. On the basis of this consideration, professional practice standards should encourage a Vet- erinarian to bring up the issues outlined in Table 2. Among veterinarians, it is widely held that acquiring IC means protecting themselves from a legal point of view. Written consent does not guarantee this. A signed consent form may supply evidence that consent was given, but not that counselling was necessarily sufficient, appropriate and not negligent. Some IC forms that are used in the veterinary field contain clauses that exempt them from responsibility for surgery carried out without any previous diagnostic tests. In truth, such a form, though signed by the client, can never protect a Veterinarian from non-voluntary respon- sibilities, caused by negligence (culpa in omittendo), imprudence (culpa in agendo), inexperience (culpa in adempiendo), or breach of laws, regulations, orders and disciplines [16]. Table 2. Information to be Disclosed During Discussion of Consent. 1. Results of pertinent diagnostic studies 2. Probable outcome of surgery 3. Likely benefits of surgery 4. Explanation of what surgery will entail 5. Probable complications 6. Temporary complications (e.g. pain, infection) and therapeutic steps to correct them 7. Permanent results and complications (e.g. paralysis, plegia) 8. Other risks that are reasonably foreseeable 9. Reasonable alternatives to the proposed procedure An IC form can be used as evidence when a lawsuit is brought on the charge of missing, incomplete, incorrect or untrue information. However, such a form could eas- ily prove that the veterinarian has unexceptionably in- formed the owner, both from a qualitative and a quanti- tative point of view, but it could also become ruinous, if it proved the veterinarian has rashly omitted some in- formation. So, IC acquires a legal value only if it can prove that a veterinarian, though using diligence, caution and skill, and complying with laws, regulations, orders and disci- plines, has not hit the expected target for other reasons (either because the ordinary risks and dangers the client had been informed of have actually come about, or be- cause the fortuitous or unforeseen events inherent in any medical activity have taken place). 6. CONCLUDING REMARKS The ever-growing importance attributed to IC is proof of a desire for quality in the physician-patient relation- ship, because it puts the patient's rights first, and then the physician’s duties. We must remember, however, that drawing up a form and having it signed does not in itself exempt a physic- cian from legal and/or disciplinary responsibilities, while real and concrete information given to the patient and the consequent concession of the necessary IC can. In the VCPR, the veterinarian’s role is crucial: al- though in the case of surgical treatment to be carried out on the animal, he/she is not the only one who can decide in the process that leads to a shared and responsible choice, he/she is the one charged with the greatest re- sponsibilities, on account of his/her scientific knowledge and skills [17]. All this must be connected with a precise duty to in- form clients of the negative consequences of some of  A. Passantino et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 128-134 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 133 their behavior to animals. Openly accessible at Although there are no specific norms on the matter, the Italian veterinarians could keep pace with the new European ethical principles. This is the trend of the Code of Good Veterinary Practice with the purpose of setting European standards for veterinarians’ ethical and be- haveioral principles “vets must gain their clients’ trust by providing exhaustive communication and supplying ap- propriate information”. In overview, information takes over the main role, as a way to solve problems or, at least, make all the people involved feel responsible, and consequently mitigate possible conflicts between Veterinarian and their clients. On the basis of the aforesaid considerations, we hope legislators will take the initiative to regulate the matter throughout the country with specific norms, which re- quire veterinarian to apply for IC not only by the Italian Ethical Code, but by a special law. At present there are no such laws. This would give a greater dignity to patient-animals and, in line with the national and European rules con- cerning well-being and protection of animals, would confirm their status as “sentient beings” [18,19] and confer moral rights [20]. REFERENCES [1] Ferrando, G. (1998) Consenso informato del paziente e responsabilità del medico, principi, problemi e linee di tendenza. Rivista Critica di Diritto Privato, 22, 49-66. [2] Appelbaum, P.S., Lidz, C.W. and Meisel, A.M. (1987) Informed consent: Legal theory and clinical practice., Oxford University Press, New York, 95, 314-317. [3] Dworkin, G. (1988) The theory and practice of autonomy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, (First publish- ed), 1-175. [4] Council of Europe (1997) Convention for the protection of Human Rights and dignity of the human being with regard to the application of biology and medicine: Con- vention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. Council of Europe, Oviedo, 4. [5] Comitato Nazonale di Bioetica. Informazione e consenso all’atto medico. Casa editrice Roma, 1992. http://www.governo.it/bioetica/pdf/9.pdf [6] Pizzamiglio, S. (2006) Consenso informato: Non un obbligo, ma una buona pratica. La professione vete- rinaria, 20, 17-23. [7] Mallardi, V. (2005) The origin of informed consent. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital, 25, 312-327. [8] Introna, F. (1998) Consenso informato e rifiuto ragionato, L’informazione deve essere dettagliata o sommaria? Rivista Italiana di Medicina Legale, 20, 821-830. [9] Fassò, G. (2001) Storia della filosofia del diritto. Laterza, Bari, 3. [10] Magnelli, G. (2002) Il consenso informato nella con- sulenza oncologica in ambito previdenziale. Rassegna di Medicina Legale Previdenziale, 3, 74-78. [11] Faden, R.R. and Beauchamp, T.L. (1986) A history and theory of informed consent. New York and Oxford: Ox- ford University Press, 261-262. [12] Fettman, M.J. and Rollin, B.E. (2002) Modern elements of informed consent for general veterinary practitioners. Journal of America n Veterinary Medical Association , 221, 1386-1393. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.221.1386 [13] Suchman, A.L., Markakis, K., Beckman, H.B. and Frankel, R.M. (1997) A model of empathic comm- unica- tion in the medical interview. Journal of the Am- erican Medical Associati on, 277, 678-682. doi:10.1001/jama.277.8.678 [14] Travaline, J.M., Ruchinskas, R. and D’Alonzo, G.E. (2005) Patient-physician communication: Why and how. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 1, 13-18. [15] Fallowfield, L. and Jenkins, V. (2004) Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet, 363, 3- 12-319. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15392-5 [16] Passantino, A. (2002) La colpa professionale in medicina veterinaria. Rivista Italiana di Medicina Legale, 4, 1061-1077. [17] Santori, P. and Canavacci, L. (2000) Le procedure per una decisione clinica informata e responsabile. Rifles- sioni critiche sul così detto “consenso informato” in vet- erinaria―Documenti del Comitato di Bioetico per la Ve te rinaria. C.G. Edizioni Medico Scientifiche, Torino. [18] European Community (2007) Treaty of Lisbon amending the treaty on European Union and the treaty establishing the European Community, signed at Lisbon, 13 Decem- ber 2007. Official Journal of the European Union, 306, 1-271. [19] Camm, T. and Bowles, D. (2000) Animal welfare and the treaty of Rome-legal analysis of the protocol on animal welfare standards in the European Union. Journal of En- vironmental Law, 12, 197-205. doi:10.1093/jel/12.2.197 [20] Passantino, A. (2008) Companion animals: An examina- tion of their legal classification in Italy and the impact on their welfare, actually and prospective. Journal of Animal Law, 4, 59-92.  A. Passantino et al. / Open Journal of Animal Sciences 1 (2011) 128-134 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJAS/ 134 Box 1. Consent to medical treatment and the related diagnostic tests. (facsimile) Date.......................... Owner/Owner’s Agent:.................................................. Mr/Mrs. Surname: ....................................................... Name: ................................................................. Address: ........................................................................Town: ....................................................................... Contact Telephone Number(s): .................................... Mobile: .................................................... Animal/Herd/Flock ID(*): …………………………. Animal Name: ………………...……………………. Species: …………………………………………… Sex: Male/Female Breed: ..................................................... Colour: ...................................Age: ............................ Reason for the medical examination:................................................................................................ Authorizes Doctor .......................................................... and his/her staff to examine and/or treat and/or carry out the diagnostic tests they deem necessary on the basis of the examination and the related tests. Allows them to administer sedatives and/or anesthetics to carry out the necessary instrumental tests, declaring he/she has been informed of the fact that such tests are not exempt from general complications, even if made with skill, diligence and prudence. Reaffirms his/her IC to Doctor........................................, who has clearly explained the reasons for which the aforesaid treatments and/or tests are necessary, also illustrating the risks of the potential contraindications, complications and/or reactions. Confirms having read and perfectly understood this authorization form, for carrying out medical treatments and diagnostic tests on the above identified animal, according to the current norms. At the time of the release of the animal from the veterinarian’s consulting rooms, the owner will take on the job of scrupulously watching it and immediately communicating to the responsible Veterinarian any complications or accidents that may have arisen or that can negatively affect the outcome of the surgery or treatment done. The undersigned also declares he/she will fully pay the costs of the veterinary service that is to be done on his/her animal, presumably between a minimum of .................... Euros and a maximum of ............................ Euros, if no events, not foreseen in the estimate, take place. Gives permission for the possible after-death inspection, in case of death of his/her animal. (*) If the dog is not microchipped, the owner/holder of the animal is informed of his/her obligation to have the animal electronically microchipped, according to the Law no.281/91. Date ............................................................. Full signature of the owner/holder to testify information and acceptance .........................................................

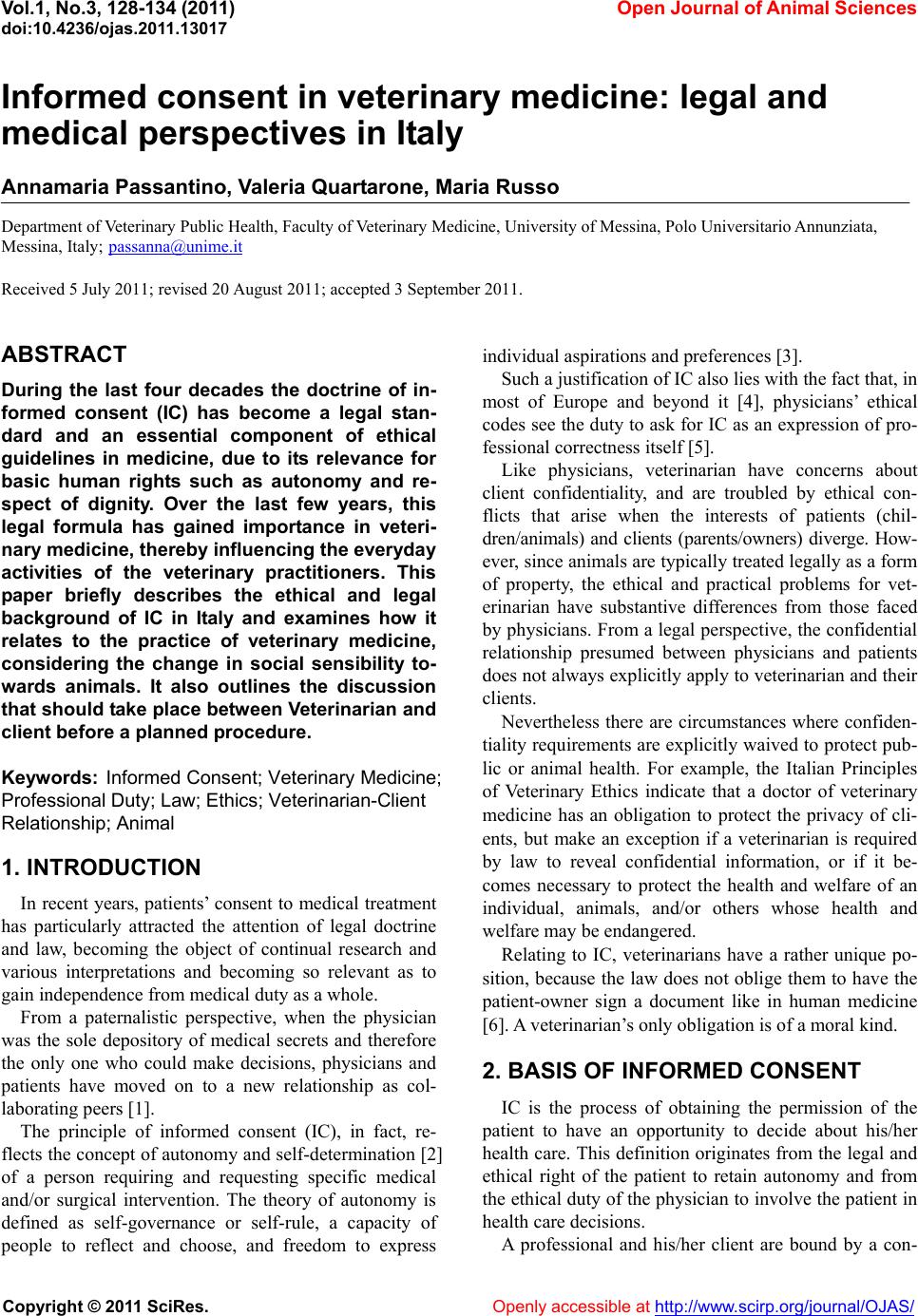

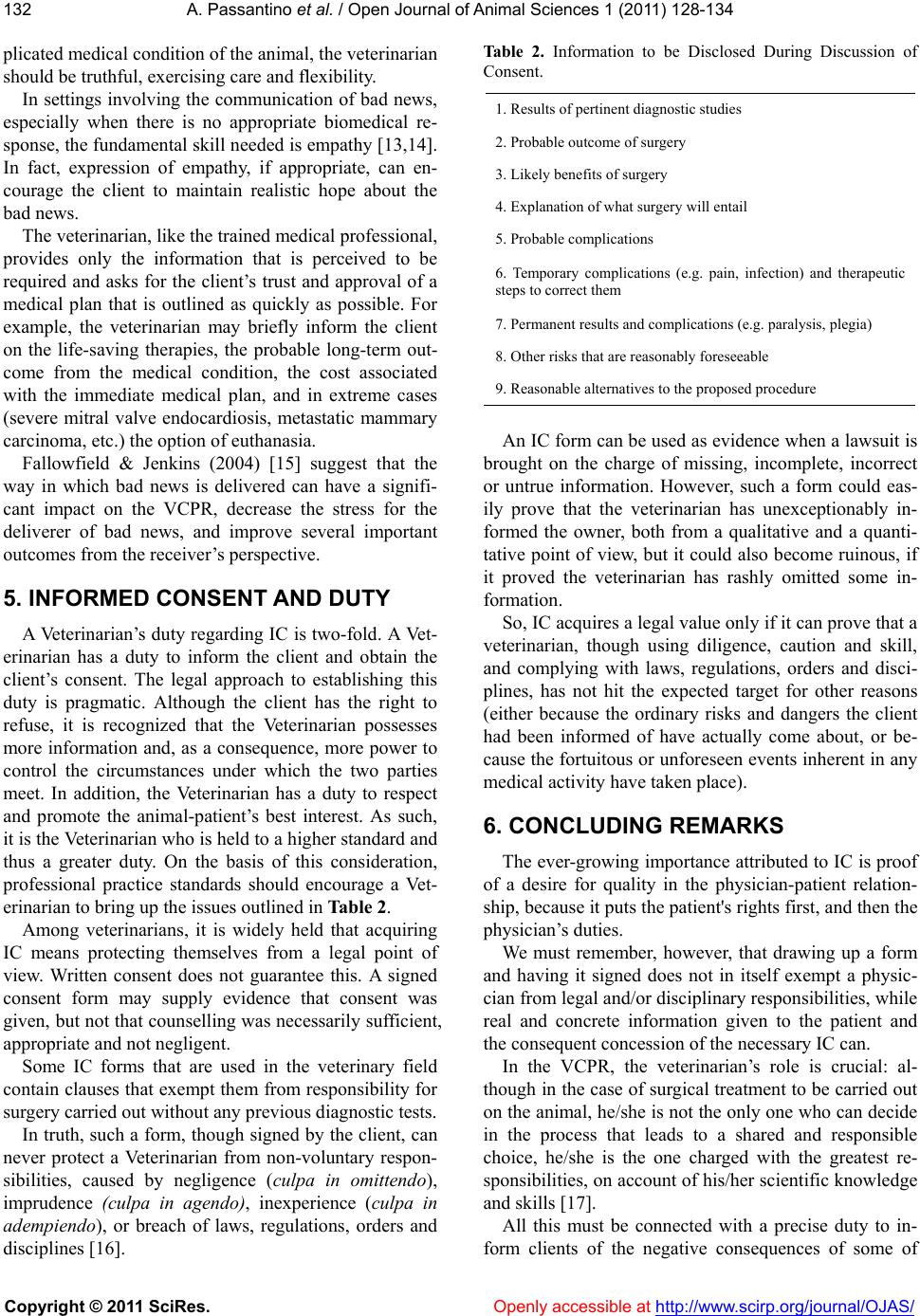

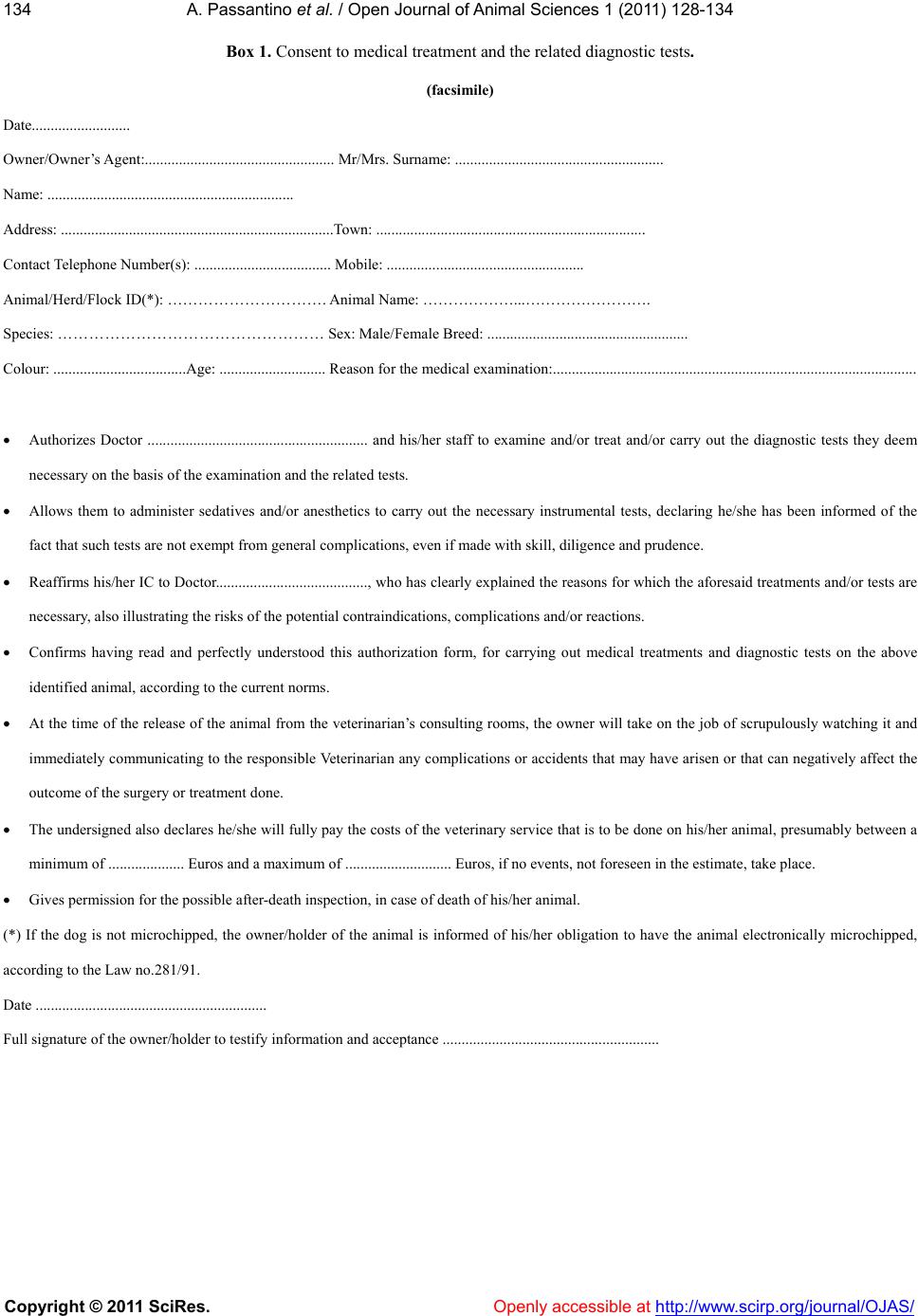

|