World Journal of Engineering and Technology

Vol.05 No.03(2017), Article ID:78323,11 pages

10.4236/wjet.2017.53B001

Compared Study of Authentic Culture on Three Guangdong Ancestral Temples

Yifeng Wen

School of Architecture and Urban Planning, The Research Center of Cantonese Culture, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China

Received: May 20, 2017; Accepted: August 8, 2017; Published: August 11, 2017

ABSTRACT

In this article, three Guangdong’s ancestral temples are taken as case studies to explore strategies for cultural heritage conservation. Heritage conservation is very important not only for our missing of past, but in order that our own cultural identity can be formed today. In China, different stakeholders hold various views on heritage protection and conflicts often take place. Particularly, many folk religion’s cultural heritages face a dangerous scenario and could even be damaged or destroyed for a variety of “reason”. This article tries to re-examine fundamental values and assessment criteria for cultural heritage conservation. The authenticity is a core concept involved with those of issues. Based on the views of culture place, the author puts forward the concept of “emic culture authenticity” as a hinge to explore authentic culture ecology of heritage and its model, to facilitate the cultural heritage conservation and reuse by the strategies of classification and adaptation.

Keywords:

Heritage Conservation, Ancestral Temple, Folk Religion, Culture Authenticity, Adaptive Strategy

1. Introduction

Since Reform and Opening-up in China, Guangdong has been at the frontier of the national economic development. Especially the Pearl River Delta region, in accordance with per capita JDP, has entered the level of middle-income countries [1]. Under the new circumstances of social/economic progress and its transformation, Guangdong government put forward a policy of “strategic cultural province”. Cultural industry has been highlighted and heritage conservation has been drawing broad attention.

In response with the needs of “strategic cultural province” for Guangdong, this article takes three Guangdong’s ancestral temples as case studies, to explore related theories and practical strategies for architectural/culture heritage conservation and reuse. In today conservation can no longer be based on the object’s intrinsic quality; it must be founded on our ability to recognize its social, aesthetic, historic, religious values etc., upon which our own cultural identity can be built [2].

2. The Cases of Three Guangdong Ancestral Temples

Architectural/Cultural heritage has drawn increasing attention in recent years in Guangdong, but there are problems like division of disciplines, scattered academic views, etc. For cultural heritage conservation, main issues should be solved immediately are: 1) how to integrate heritage’s material preservation with protection of intangible cultural heritage in an organic and sustainable way; and 2) how to reconcile different focus/interests of different stakeholders in heritage conservation process. Below passages will further explore these issues by examples of Three Guangdong’s Ancestral Temples.

2.1. Yuecheng’s Dragon Mother Temple

Three Guangdong’s ancestral temples are very representative heritages of Guangdong province. The Yuecheng’s Dragon Mother Temple is located in Yue cheng town beside the Xijiang River in county Deqing, Guangdong. Dragon is a water god, so all dragon-mother temples are nearby river; among all those temples, the Yuecheng’s Dragon Mother Temple as progenitor is the most grandeur and spectacular one [3], as shown in Figure 1.

As an original culture rooted in long history and tradition, the kernel of dragon-mother worship is a nature/totem worship of dragon combined with worship of Great Mother [4], with which producing a lot of vital religious images and symbolic, creating fundamental life meanings for Xijiang River people over thousand years. However, in the rise and wave of exploitation, or “culture-led regeneration”, the cultural development game seems far from being a “win-win” one [5]. Cultural heritage is implicated in the complicated choices made by local and ordinary individuals in the face of political control and capital accumulation [6]. We should alarm that the transformation of authentic culture under the guise of urban/government entrepreneurialism and the ubiquitous logic of

Figure 1. Dragon mother temple.

commodification is whether right and sustainable?

Dragon Mother Temple is still mainly a place for the folk religion. Now the temple faced tourism exploitation and strong government’s involvement, which have been diluting the “original taste and flavor” of this indigenous culture. The commodification is, for the most part, beyond the control of the locals which often stay marginalized. As an authentic culture heritage and a religious site under using, the Dragon Mother Temple carries a living folk religious service as its main function. Even in a view of “evolutionary adaptation”, tourism development or other exploitation also must be based on the foundation of its cultural authenticity otherwise we cannot expect it will be sustainable.

2.2. Foshan North Lord Temple

Foshan was Located in the downstream of the Xijiang River basin. Foshan with its economic power in late feudal periods was very famous for its tradition of ritual and sacrifice, and the Foshan North Lord Temple is the most important religious place, as shown in Figure 2. The development of Foshan North Lord worship had two phases. One is primary stage of Longzhu (Flying Dragon) Shrine which was a building for pure folk religion in early agricultural society. The second stage from Zhengtong 14th year (1449) of Ming Dynasty was the shrine in its sacrifice got involving by government intervention was called as Lingying (spiritual responding) Temple [7], which marked a beginning of opening up process in Foshan from a rural society to outward world. The folk temple had been designated as official religious place, became a glory of local people. The big hall of the temple thus had gradually paid a role as local autonomous government, becoming place for arbitration and civil management, also being the most important local academy [8].

Because of its advantage in aspects of architectural aesthetics, historical memory, cultural taste and place making, in North Lord Temple’s historic district, a renewal project Lingnan Tiandi has been developing. This renovation project tries to answer the question how to do with industry transformation, urban transformation and environment reconstruction, and exploring scientific development pattern, which is attracting wide range attention and creating appeal of the city, as shown in Figure 3. However, couple with the problem of gentrification, the practice of Lingnan Tiandi project also triggers a doubt concerning

Figure 2. North Lord Temple.

Figure 3. Lingnan Tiandi.

culture authenticity.

2.3. Guangzhou Chen Clan Academy

Guangzhou and Foshan are adjacent to each other in the center of the Pearl River Delta. In the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Guangzhou and Foshan together form a dual center, connecting the Pearl River Delta with several southeast provinces and overseas region, creating a great economic network at home and abroad. Because Guangzhou’s special geographical location, from ancient to modern times, the Guangzhou’s most outstanding cultural traits are fusion the native culture and Central China culture with overseas culture, which provides a base for produced a mixed cultural phenomenon of Guangzhou Chen Clan Academy.

The Guangzhou Chen Clan Academy also called as Chen Clan Ancestral Temple, as shown in Figure 4. The Chen Clan Ancestral Temple is not just a conventional clan ancestral temple, because it is a collection of three properties including ancestral temple, academy and guild hall in one architecture complex, that just reflects the deep structure of social ethics expounded by Hegel which including three layer ethical relationship: family, civil society and state. In modern transition time, various revolutionary regimes and other regimes had changed frequently in Guangzhou, as well as with the intervention of foreign forces, making the political situation in Guangzhou highly unstable, which means a long-term effective national ethics is not fully established and institutional supply could not be effectively provided , therefore people can only returned to clan-based kinships as natural ethics to sustain a social structure for their own survival and development needs. A large number of architectures like Chen Clan Academy appeared in the Pearl River Delta in the middle and later periods of Qing Dynasty, particularly in Guangzhou, reflected this kind of chaos situation.

The three Guangdong’s ancestral temples are not only three isolated architectures, but also represent the history and the development of a series of correlated cultural landscape in Cantonese geographical area.

3. The Ecology of Authentic Culture and Heritage Sustainable Conservation

3.1. The Authenticity

How to explore the aim and the value of cultural heritage conservation from a

Figure 4. Chen Clan Academy.

much more fundamental level, seeking universal and profound concepts and evaluation standard for heritage that become crucial. Those issues cannot be apart from discussion of a concept “authenticity”.

The concept of authenticity in historic preservation in terms of modern sense originated from that the enlightenment of the eighteenth century brought new historical consciousness for Europe. With the accumulation of historical research and protection practice, the concept of historic building conservation becomes diverse and complex. In 1964 the Venice Charter (The International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites) laid the foundation of meaning about authenticity in the fields of international heritage protection in modern time. In 1994 the Nara Document on Authenticity is certain that the “authenticity” is a basic concept for definition, assessment and monitoring of cultural heritage. Due to the diversity of world culture and cultural heritage, it is realized that the evaluation of their authenticity cannot be put into fixed standard, and the concept and application of authenticity should root in heritage respective cultural context.

Authenticity is not only as a conventional topic for cultural heritage conservation that focusing on object-related authenticity, but a wide use concept. Since MacCannell (1973, 1976) introduced the concept of authenticity to sociological studies of tourist motivations and experiences, the subject has become a topic for tourism study. Based on tourism studies, the three different approaches―objec- tivism, constructivism, and postmodernism―are reviewed and analyzed by Wang and the limits of the conventional concept of authenticity (object-related authenticity) are also exposed. It is suggested that existential authenticity is an alternative source in tourism, regardless of whether the toured objects are authentic [9]. Objective authenticity, according to Wang, involves a museum- linked usage of the authenticity of the originals to which an absolute and objective criterion used to measure it. While by constructive authenticity it is meant the result of social construction, not an objectively measurable quality; Things appear authentic not because they are inherently authentic but because they are constructed as such in terms of points of view, beliefs, perspectives, or powers. This notion is thus relative, negotiable [10], contextually determined [11] and even ideological [12]. Existential authenticity, in terms of Existentialism or common sense, denotes a special state of Being in which one is true to oneself. According to Heidegger (1962), to ask about the meaning of Being is to look for the meaning of authenticity.

Some researchers try to bridge the conceptual gaps between varied notions. As Jillian M. Rickly-Boyd (2012) argued that the dichotomy is problematic because it obscures the way that toured sites/objects and social discourses often exist in dialogue with experiences of existential authenticity [13]. It cannot liberate existential authenticity from object and place even according to existentialist and phenomenological traditions.

The discussions/theories need to say giving tremendous revelation and inspiration. But none of these theories is entailing univocal answers and a fully- fledged “paradigm”. To deal with a complex situation based on the existing theory related to “authenticity”, This research developed a model to integrate those concepts; it put forward a concept of “emic authenticity” as a corner stone to build a architecture of authentic culture ecology to handle those issues, which based on a fundamental thoughts which is that starting from the rationale of anyone stakeholder’s view don't have the rationality represented as the whole, however they can logically be constituted as parts of the whole system of cultural ecology of authentic culture related with cultural heritage conservation and use. According to this line of thoughts, the concepts “emic” and “etic” put forward by linguist Kenneth Pike, late used by Marvin Harris’ in culture theory [14], are used for reference. Here it first divides related people as two groups: 1) people with “emic” positon, and 2) people with “etic” positon. The “emic” position, in this paper, is defined by the status that people take part in certain culture activity such as ritual, ceremony, etc., and the time that people engage in the culture activity beyond as bystander and spectator or as common participating with recreation and entertainment which are not so much involving deep sentiment or with religiosity in religious fair and service, etc. Except the “emic” position, all other participation can be defined as “etic” position including sectors such as government, scholar, tourist, developer and so on.

Here gives the Diamond Model of authentic cultural ecology as shown in Figure 5. Objective authenticity is reference to heritage material/physical authenticity. Subjective authenticity as mentioned before, its concept originated from Existentialism, emphasizing an existential experience of ‘true self’, and ac-

Figure 5. Diamond Model of authentic cultural ecology.

cording to this view cultural/heritage authenticity or that of its value after all is evaluated by subjective/existential experience. Etic authenticity means an experience of outside community not as local with emic position to participate the activity related to the heritage, mainly thorough social-constructed manner to achieve evaluation, authentication and appreciation toward heritage. Emic authenticity contrast with that of etic one is originated from the heritage as a culture place correlated with “natural context” and “real life” of local community. The Diamond Model of authentic cultural ecology can unlock a conceptual mess and obfuscation among the antecedents, indicators and consequences of authenticity. The logical and structural model can be used for their definition interoperability between concepts.

Figure 5 indicates that the emic authenticity is interactive with all other authenticity in a reciprocal manner, and at the core of culture ecological niche of heritage. Existed some material/physical site or culture place is precondition for cultural heritage, while the meaning of this objective reality is only established by the emic culture and local community. Etic authenticity in itself is relatively to the emic authenticity and relies on it. The subjective/existential authenticity are often interaction with depth to emic: on the one hand, an individual with emic authenticity must already be a person with subjective/existential authenticity experience; on the other hand, the participants as etic position experienced deep subjective authenticity must base on their experience toward emic authenticity as necessary precondition―that is, the result of deep etic subjective authenticity is not just the emic local cater for their enjoyment by performance, but is that, the emic local is more immerse in their own culture, the etic participants will produce more their own deep subjective/existential experience. The Diamond Model of authentic cultural ecology forms a cycle among the different species of authenticity by which the energy of authentic culture recycling.

3.2. The Quantification of “Emic” Positon and Culture Authenticity

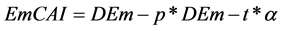

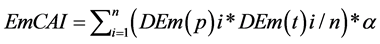

Emic culture authenticity is complex issues, and its accurate quantification is difficult. In this research it put forward the Degree of Emic position (DEm) as most important parameter to indicate the basic aspect of emic culture authenticity. DEm is composed by two figures: one (DEm-p) is the percentage of people’s number with emic position in certain culture activity related to the heritage; another (DEm-t) is the percentage of the time of full engagement by people with emic position and deep sentiment in that of culture activity. In this paper, the Emic Culture Authenticity Index (EmCAI) is defined as equal to DEm-p multiply by DEm-t and modified by coefficientα:

(1)

(1)

Here, modified by coefficient α means other complementary parameters related with emic culture authenticity such as the original of heritage rooted in long history/tradition, the compared importance of the heritage site in emic community, the compared annual frequency of cultural events taken place in the heritage site, and so on. Increasing the times of observations/statistics can increase the accuracy of the index, averaging all those indexes, so:

(2)

(2)

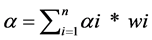

The α can be calculated by measure of weighted factors “α1, α2, …αi”, so:

(3)

(3)

Here, the wi is the weighted value of αi. But in this initial stage of research, we simply adopt the Dragon Mother Temple as benchmark (α = 1) to compare with two other temples, directly giving a comprehensive value (α = 0.9) to the North Lord Temple, and another one (α = 0.5) to the Chan Clan Academy. The indexes of three Guangdong ancestral temples as shown in Table 1, the figures of DEm-p and DEm-t which come from many times observation adopt the multiple of 0.05 that means the figures are not accurate sense in terms of difficult process of the observation for avoiding problems such as sometime repeatedly counting same person as different people. Nevertheless, the figures of Table 1 have still important significance to illustrate the basic situation in three Guangdong ancestral temples.

Here, the “rule of golden ratio” is used to evaluation. The meaning of the golden ratio is that it is a sensitive figure of majority or minority, and a sensitive proportion concerning subject position or object status and their compared power inflecting by each other. When EmCAI is above 0.618, which indicates the emic culture authenticity is substantial and solid, and outside world has little influence on the culture related to the heritage. If the EmCAI is below 0.382, which means the culture is losing authenticity or taking place of variation/alienation. When the EmCAI figure is between 0.618 and 0.382, the culture authenticity is in a sensitive and transitive stage. In nowadays we emphasize that the value of culture heritage mostly lie in its involving with contemporary life through intertexture and mutual narration between emic and etic position, so the CAI between 0.5 and 0.618 is encouraged by this research that indicate a heritage not only maintaining its culture authenticity, also having a vigorous life, that is to say, the culture heritage not only plays a role in mechanically integration of solid

Table 1. The main information and indexes of three Guangdong ancestral temples.

Notes: 1) Scale including two figures: the former refer to whole temple’s area, the later refer main architecture’s floor area. 2) Similar temples refer to the number of temples in which worshiping same god or having similar religious significance in Guangdong Province.

traditional community, but organically integration with contemporary life and helping construction of new cultural identity.

3.3. Heritage’s Sustainability and Adaptive Reuse

The emic authenticity of cultural heritage is deeply involved with heritage conservation sustainability, which means that heritage meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs development [15].

From Table 1, we can see that the culture of Dragon Mother Temple is good emic authenticity (EmCAI = 0.585). But in recent years the tourism exploitation and outside interference is damaging the authenticity of this original culture. The planning/exploitation process of these sites/heritages dominated by government still lack a holistic approach and genuine engagement with local communities. Dragon Mother Temple’s culture as an original culture’s matrix with irreplaceable resources retains ancient cultural memory, witnessed the history of human cultural evolution. Its sustainable conservation strategy should base on that taking its advantage for culture storage, culture inheritance and culture creation by a nature way instead of any unnecessary/external interference for some short-term effects.

With regard to the Foshan North Lord Temple, as Table 1 shown (EmCAI = 0.135), the authenticity of emic/traditional culture had been damaged. Foshan as a national historic city have deep cultural accumulation and rich cultural connotation. The North Lord Temple Fair is a dispensable part of the cultural heritage, it happened in the most prosperous period in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, but discontinued in the period of the Republic of China. In 2005, Because of the drive of the intangible cultural heritage protection, North Lord Temple fair finally returned to Foshan’s city life. The revival temple fair not only inherited the traditional connotations, but also infused new culture atmosphere, forming a new ritual contents and characteristics [16]. Now the temple fair is just on the road to revival, how to make it keeping fresh vitality and advance with the times, becoming a positive force for the construction of local culture, that is the issues we face today.

With regard to the Chen Clan Academy, the EmCAI is zero, the emic/tradi- tional culture of that temple is death, so it just as a museum having its functions for culture/education’s exhibition and tourism development. The Chen Clan Academy, as one of the “Guangzhou New-century Top Eight Spots”, named as “Enduring Splendor of Chen Clan Academy”, being a famous city brand to producing some spillover effects for surrounding areas and even for whole Guangzhou.

All three Guangdong ancestral temples were built or rebuilt in the later Qing Dynasty, so compared with the value of heritage’s architecture, the more important things in terms of temple’s cultural heritages are their roles in maintaining and creating living culture, place making, and city etherealization.

4. Conclusions

The main theory contribution of this paper is putting forward a Diamond Model of authentic cultural ecology for logically clear up those concepts related to “authenticity”. EmCAI is used to tackle with the issues of heritage’s authentic culture, to classify heritage as different types with differentiated sociological significance in today to employ adaptive and sustainable strategies for their conservation and exploitation.

For cultural heritage of three Guangdong ancestral temples and Guangdong constructing “strategic cultural province”, the important things are that this study demonstrates how Chinese cities are shaped by the practices of global consumerism, and the local neoliberal logic of entrepreneurialism behind the rhetoric of “cultural approach”. It should be alarm that the short-term effects of economic benefits may be destroy the long-term cultural memory and affect the culture safety resulted by losing cultural gene and disappearing cultural species. Sustainable renewal is the proper management of use and change in and around historic places and spaces, so as to respect and enhance their value to society. Cultural sector based in the community who has more local experiential knowledge, emotional attachment and historical narratives/memories are indispensable elements for emic culture authenticity, place making and heritage sustainable reuse.

Acknowledgements

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Cite this paper

Wen, Y.F. (2017) Compared Study of Authentic Culture on Three Guangdong Ancestral Temples. World Journal of Engineering and Technology, 5, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4236/wjet.2017.53B001

References

- 1. Guangzhou Municipal Statistics Bureau. (2013) Guangzhou Survey Office of National Bureau of Statistics. Guangzhou Statistical Yearbook, China Statistic Press.

- 2. Vecco, M. (2010) A Definition of Cultural Heritage: From the Tangible to the Intangible. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 11, 321-324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2010.01.006

- 3. Wen, Y.F. (2011) Research on Folk Religion Culture and Archetype of the Long Mu Temple Located in Deqing. Journal of Guangzhou University (Social Science Edition), 11, 81-87.

- 4. Neumann, E. (1991) The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Princeton University Press.

- 5. Sacco, P., Ferilli, G. and Blessi, G.T. (2014) Under-standing Culture-Led Local Development: A Critique of Alternative Theoretical Explanations. Urban Studies, 51, 2806–2821. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013512876

- 6. Su, X.B. (2015) Urban Entrepreneurialism and the Commodification of Heritage in China. Urban Studies, 52, 2874-2889.

- 7. Foshan City Museum. (2005) Foshan Ancestral Temple. Cultural Relics Publishing House, Beijing.

- 8. Wen, Y.F. (2015) The Worship Culture and Sociological Meaning of Three Guangdong’s Ancestral Temples. Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture Research, 2, 667-675.

- 9. Wang, N. (1999) Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Expe-rience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26, 349-370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

- 10. Cohen. (1988) Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 15, 371-386. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X

- 11. Salamone, F.A. (1997) Authenticity in Tourism: The San Angel Inns. Annals of Tourism Research, 24, 305-321.

- 12. Silver, I. (1993) Marketing Authenticity in Third World Countries. Annals of Tourism Research, 20, 302-318.

- 13. Rickly-Boyd, J.M. (2012) Authenticity & Aura a Benjaminian Approach to Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39, 269-289.

- 14. Harris, M. (1979) Cultural Materialism: The Struggle for a Science of Culture. Random House, New York, 32.

- 15. United Nations. (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm

- 16. Sun, L.-X. (2012) The Revival of Foshan Zumiao Temple Fair. Journal of Foshan University (Social Science Edition), 3, 12-16.