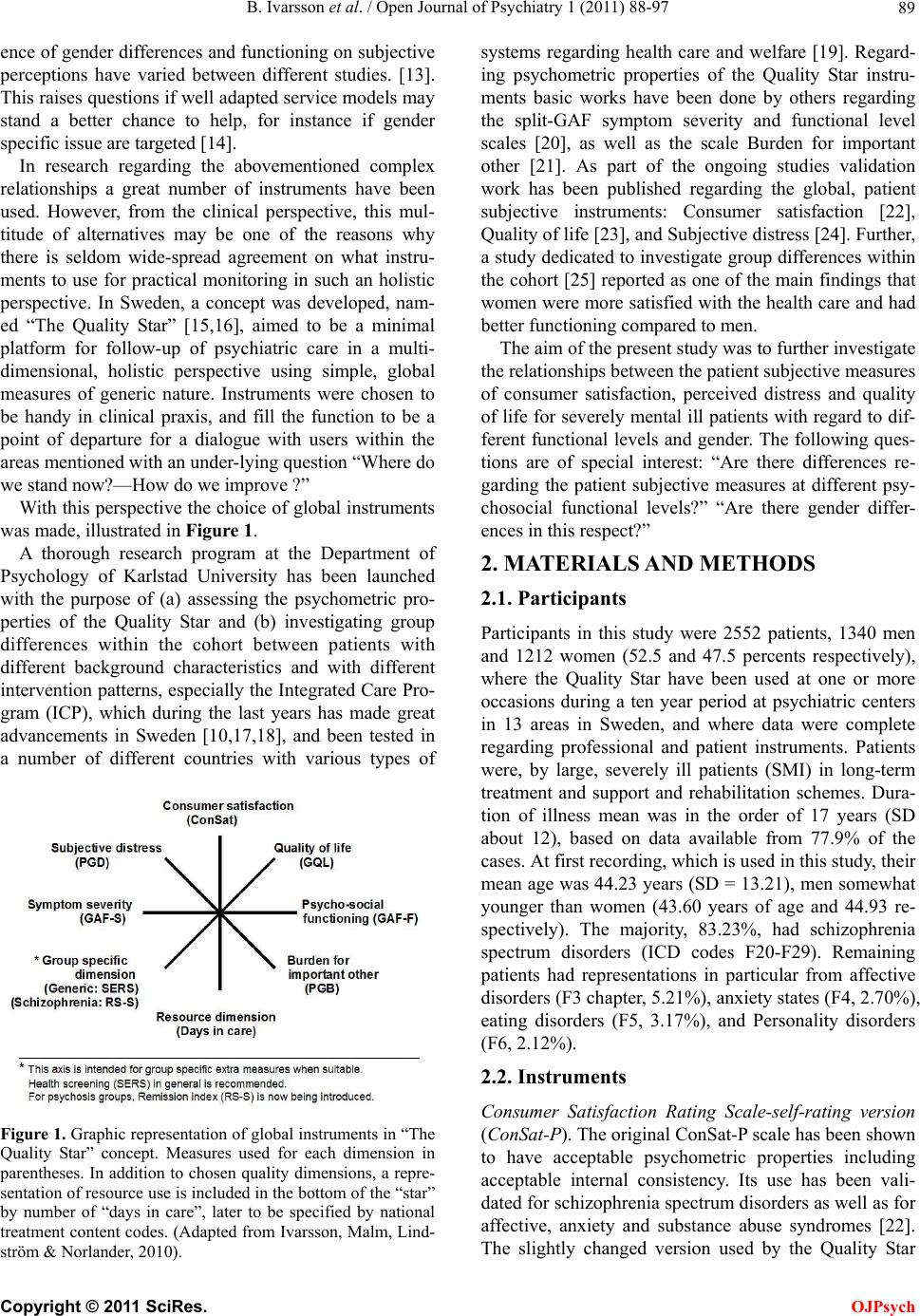

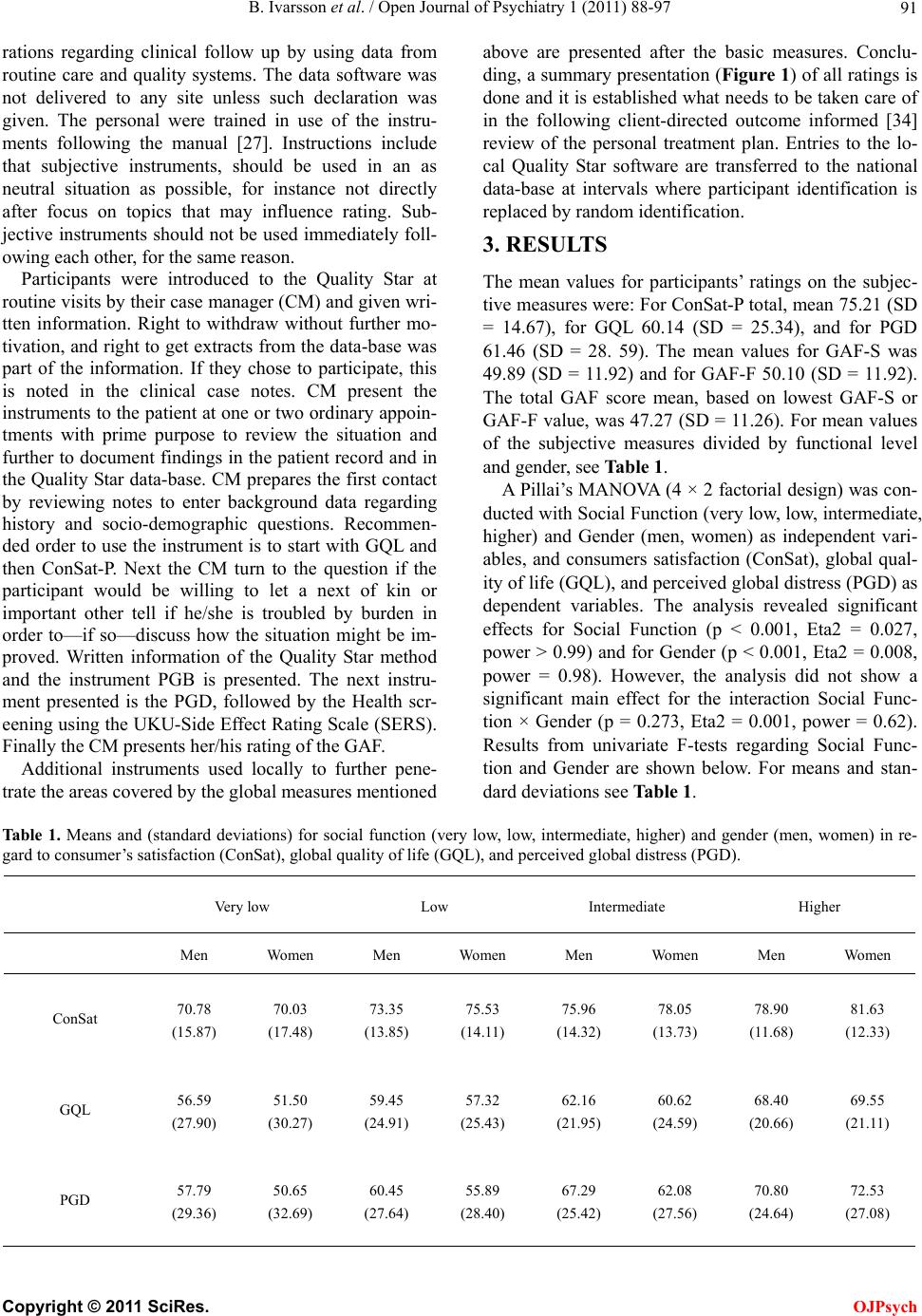

Open Journal of Psychiatry, 2011, 1, 88-97 doi:10.4236/ojpsych.2011.13013 Published Online October 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJPsych/ OJPsych ). Published Online October 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJP sych Consumer satisfaction, quality of life and distress with regard to social function and gender in severe mental illness* Bo Ivarsson1,4# , Leif Lindström2, Ulf Malm3, Torsten Norlander4 1Psychiatric Services, Borås Hospital, Borås, Sweden; 2Department of Neuroscience, Psychiatry, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden; 3Institution for Clinical Neuropsychiatry, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden; 4Department of Psychology, Karlstad University, Karlstad, Sweden. Email: #bo.ivarsson@vgregion.se; bo.ivarsson@bornet.net Received 5 July 2011; revised 10 August 2011; accepted 17 August 2011. ABSTRACT OBJECTIVE: The relationships between subjective satisfaction, distress and quality of life for severely mental ill patients with different functional levels and gender was investigated in a multi-center cohort, using a balanced mix of subjective and clinician rat- ings in an outcome-informed model for a clinical management based on shared decision making, “The Quality Star”. METHODS: Naturalistic data for 2552 pe rso ns , mainly with s chizophrenia diagnoses, in lo ng- term treatment and rehabilitation, were analyzed in a cross-sectional study. RESULTS: With increasing Social Function, rated with the split-GAF Disability/ Functioning scale, the better were patients’ Satis- faction, subjective Quality of life and Perceived Glo- bal Distress. Women were more satisfied with the care but a lso more distres sed. CONCLUSION: Main findings were in line with other studies. However, the gender differences are in line with some, but not with other, studies. This poses questions how patient fac- tors, instrument constructs, and treatment, especially shared decision making, influence subjective reports. Keywords: Consumer Satisfaction; Quality of Life; Per- ceived Distress; Schizophrenia; Social Function 1. INTRODUCTION In addition to the continuous refinement of instruments for diagnosis and measurement of change in terms of psychopathology, development of instruments for mea- suring social functioning and patient subjective aspects has become increasingly important, as emphasized in a recent review of instruments for social functioning in serious mental illnesses with the title “Functioning is the cornerstone of life” [1]. Specifically regarding schizo- phrenia it was noted in another review that social func- tion is re-emerging as an important outcome measure, though psychometrics and direct comparisons between differing social function instruments, and their relation to quality of life is unclear [2]. The increasing importance of functioning in the treatment, rehabilitation and recovery is also mirrored in the ongoing revision of the DSM and ICD classifications ,as well as in the introduction of the WHO International Classification of Functioning (ICF) [ex. 3-5] . There is also broad recogn ition of findings that impro- vement, as a rule, is related to services being given in a way that is perceiv ed with satisfact i o n by the users [6- 9] . A topic with relation to patient satisfaction is the im- portance of open and respectful dialogue with patients, keeping in focus the pu rely patient subjective perception of distress and quality of life as a sound basis for ach- ieving treatment alliance, shared decision making and user empowerment [10-12]. There are numerous constructs within these general areas, and for instance, McCabe et al. address different patient-related outcomes in the context of schizophrenia, their relevant constructs, associated scales and key emp- irical findings within outcomes relating to a) illness and treatment, with emphasis in the areas: needs for care, tr- eatment satisfaction, therapeutic relationship, clinical communication, self-rated symptoms, insight, and b) psychological well-being and resilien ce of self, with spe- cial mention to empowerment, self-esteem, sense of coh- erence and recovery [12]. *Author’s notes: The research plan has been evaluated and approved by the Regional Ethical Vetting Board in Uppsala and the study followed the ethical standards of the World Medical Association declaration o Helsinki concerning Ethical Principles of Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. The authors declare that they have no competing interests. It is also noteworthy that findings regarding the influ-  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 89 ence of gender differences and functioning on subjective perceptions have varied between different studies. [13]. This raises questions if well adapted service models may stand a better chance to help, for instance if gender specific issue are targeted [14]. In research regarding the abovementioned complex relationships a great number of instruments have been used. However, from the clinical perspective, this mul- titude of alternatives may be one of the reasons why there is seldom wide-spread agreement on what instru- ments to use for practical monitoring in such an holistic perspective. In Sweden, a concept was developed, nam- ed “The Quality Star” [15,16], aimed to be a minimal platform for follow-up of psychiatric care in a multi- dimensional, holistic perspective using simple, global measures of generic nature. Instruments were chosen to be handy in clinical praxis, and fill the function to be a point of departure for a dialogue with users within the areas mentioned with an under-l y i ng questio n “ Where do we stand now?—How do we improve ?” With this perspective the choice of global instruments was made, illustrated in Figure 1. A thorough research program at the Department of Psychology of Karlstad University has been launched with the purpose of (a) assessing the psychometric pro- perties of the Quality Star and (b) investigating group differences within the cohort between patients with different background characteristics and with different intervention pattern s, especially the Integrated Care Pro- gram (ICP), which during the last years has made great advancements in Sweden [10,17,18], and been tested in a number of different countries with various types of Figure 1. Graphic representation of global instruments in “The Quality Star” concept. Measures used for each dimension in parentheses. In addition to chosen quality dimensions, a repre- sentation of resource use is included in the bottom of the “star” by number of “days in care”, later to be specified by national treatment content codes. (Adapted from Ivarsson, Malm, Lind- ström & Norlander, 2010). systems regarding health care and welfare [19]. Regard- ing psychometric properties of the Quality Star instru- ments basic works have been done by others regarding the split-GAF symptom severity and functional level scales [20], as well as the scale Burden for important other [21]. As part of the ongoing studies validation work has been published regarding the global, patient subjective instruments: Consumer satisfaction [22], Quality of life [23], and Subjectiv e distress [24 ]. Further, a study dedicated to investigate group differences within the cohort [25] reported as one of the main findings that women were more satisfied with the health care and had better functioning compared to men. The aim of the present study was to further investigate the relationships between th e patient subjective measures of consumer satisfaction, perceived distress and quality of life for severely mental ill p atients with regard to dif- ferent functional levels and gender. The following ques- tions are of special interest: “Are there differences re- garding the patient subjective measures at different psy- chosocial functional levels?” “Are there gender differ- ences in this respect?” 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Participants Participants in this study were 2552 patients, 1340 men and 1212 women (52.5 and 47.5 percents respectively), where the Quality Star have been used at one or more occasions during a ten year period at psychiatric centers in 13 areas in Sweden, and where data were complete regarding professional and patient instruments. Patients were, by large, severely ill patients (SMI) in long-term treatment and support and rehabilitation schemes. Dura- tion of illness mean was in the order of 17 years (SD about 12), based on data available from 77.9% of the cases. At first recording, which is used in this study, their mean age was 44.23 years (SD = 13.21), men somewhat younger than women (43.60 years of age and 44.93 re- spectively). The majority, 83.23%, had schizophrenia spectrum disorders (ICD codes F20-F29). Remaining patients had representations in particular from affective disorders (F3 chapter, 5.21%), anxiety states (F4, 2.70%), eating disorders (F5, 3.17%), and Personality disorders (F6, 2.12%). 2.2. Instruments Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale-self-rating version (ConSat-P). The original ConSat-P scale has been shown to have acceptable psychometric properties including acceptable internal consistency. Its use has been vali- dated for schizophrenia spectrum disorders as well as for affective, anxiety and substance abuse syndromes [22]. The slightly changed version used by the Quality Star C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 90 network scale has 11 items in following domains: avail- ability, atmosphere, continuity, information and parti- cipation, drug treatment, psychological and psycho- social interventions, result of treatment/care and trust in future well-being. All items are rated on a seven point scale with the format in principle +3 full satisfaction, +2 satisfied but with minor dissatisfaction, +1 More satis- faction than dissatisfaction, 0 equally satisfaction/diss- atisfaction or indecisive, –1 to –3 formulated in a reci- procal fashion. Total score raw data are transformed to percentages where 0% is extreme dissatisfaction and 100% complete satisfaction. Global Quality of Life scale (GQL). The instrument is a visual analogue scale [26]. The introductory question has the wording “How do you find your life situation right now?" and the anchor-points of the visual analogue scale (VAS) line are marked “Best possible life situ- ation” and “Worst possible life situation”. The scale is a 10 cm line, thus giving a scale 0 - 100 mm, where 0 signifies the worst situation and 100 the best possible [27]. The GQL have been found valid for serious mental ill persons with acceptable psychometric properties [23]. Test-retest reliability was found satisfactory. Concurrent validity with the initial item of life satisfaction scale of MANSA, “Life as a whole”, was good (r = 0.85 and rho = 0.86). Content validity was clarified by associations with a number of validating measures. Healthy adults' ratings on the GQL, was found to be mean 76.0 (SD = 17.00). Perceived Global Distress scale (PGD). The instru- ment is a visual analogue scale [26]. The introductory question has the wording “How much have you been bothered by your psychiatric problems during the last month?” and the anchor-points of the VAS line are marked “I have not experienced any psychiatric pro- blems at all” and “My psychiatric problems have trou- bled me extremely much”. The scale is a 10 cm line, thus giving a scale 0 - 100 mm, where 0 signifies the worst situation and 100 the best possible [27]. The PGD scale has been found valid for serious mental ill persons with acceptable psychometric properties [24]. Test-retest reliability properties were found satisfactory. Concurrent validity with the last item of life satisfaction scale of MANSA, “Mental health” was (rho = 0.59). Conten t va- lidity was clarified by associations with a number of validating measures. Correlation with depression index of Symptom Check List –90 (SCL90) was rho = –0.64. Healthy adults rated mean 89.55 (SD = 19.18). Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). With this instrument professionals rate global mental health from the perspective of psychic, social, and functional ability [28]. The scale has ten vignettes exemplifying symptom severity and psychosocial functioning to be used as ref- erence in rating, each vignette representing successive 10-point intervals in the semi-quantifying in the total scale range 1 - 100. Rating 1 represents the maximum dysfunction and 100 best possible. In each vignette the first part exemplifies syndrome severity and the last part psychosocial functioning. GAF is a widely used scale and its psychometric properties are documented in sever al studies [e.g. 29-31]. The reliable use of GAF requires a conscious strategy for its use due to pit-falls in the basic instructions and guidelines [31-33]. The Quality Star net- work uses the split-GAF version, with separate ratings of symptom severity (GAF-S) and psychosocial function- ing (GAF-F) [20]. The main measures taken by the net- work to obtain reliable results include basic education, monitoring of the datab ase and calibration by participat- ing centers against a set of video cases. 2.3. Design The study was designed to clarify the importance of level of psychosocial functioning and gender for SMI patients’ subjective experience in the three patient sub- jective dimensions regularly monitored according to the Quality Star method. Thus, the dependent variables used were the scales for satisfaction with treatment and service (ConSat-P), the subjective global quality of life scale (GQL) and the perceived global mental distress scale (PGD) scales. The independent variables were gender (man/woman) and the Global functioning scale (GAF-F) according to the Split-GAF method. Four GAF-F categories were constructed based on the fre- quency distribution of data, considering that GAF-F- scores 61 and above has been suggested as a level where recovery for serious mentally ill persons is well in pro- gress, whereas GAF-F values below 30 is often seen as indicative of need for intensive treatment. As partici- pants with GAF-F values 30 and below were judged too small in numbers, it was decided to include also the 31-40 GAF-F ratings in the most severe group. Thus, the following four groups were created: GAF-F 40 and below, GAF-F 41-50, GAF-F 51-60, GAF-F 60 and above, named “Very low”, “Low”, “Intermediate”, and “Higher”. 2.4. Statistics Descriptive statistics for model variables. The model was tested with Pillai’s MANOVA regarding psychosocial function and gender. Univariate F-test and Post hoc tests, and subsequently trend tests (Difference Custom Hy- pothesis Tests) were conducted. 2.5. Procedure Decision to participate in the Quality Star network by the psychiatric departments include ethical conside- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 91 OJPsych rations regarding clinical follow up by using data from routine care and quality systems. The data software was not delivered to any site unless such declaration was given. The personal were trained in use of the instru- ments following the manual [27]. Instructions include that subjective instruments, should be used in an as neutral situation as possible, for instance not directly after focus on topics that may influence rating. Sub- jective instruments should not be used immediately foll- owing each other, for the same reason. Participants were introduced to the Quality Star at routine visits by their case manager (CM) and given wri- tten information. Right to withdraw without further mo- tivation, and right to get extracts from the data-base was part of the information. If they chose to participate, this is noted in the clinical case notes. CM present the instruments to the patient at one or two ordinary appoin- tments with prime purpose to review the situation and further to document findings in the p atient record and in the Quality Star data-base. CM prepares the first con tact by reviewing notes to enter background data regarding history and socio-demographic questions. Recommen- ded order to use the instrument is to start with GQL and then ConSat-P. Next the CM turn to the question if the participant would be willing to let a next of kin or important other tell if he/she is troubled by burden in order to—if so—discuss how the situation might be im- proved. Written information of the Quality Star method and the instrument PGB is presented. The next instru- ment presented is the PGD, followed by the Health scr- eening using the UKU-Side Effect Rating Scale (SERS). Finally the CM presents her/his rating of the GAF. Additional instruments used locally to further pene- trate the areas covered by the global measures mentioned above are presented after the basic measures. Conclu- ding, a summar y presentation (Figure 1) of all ratings is done and it is established what needs to be taken care of in the following client-directed outcome informed [34] review of the personal treatment plan. Entries to the lo- cal Quality Star software are transferred to the national data-base at intervals where participant identification is replaced by random identification. 3. RESULTS The mean values for participants’ ratings on the subjec- tive measures were: For ConSat-P to tal, mean 75.21 (SD = 14.67), for GQL 60.14 (SD = 25.34), and for PGD 61.46 (SD = 28. 59). The mean values for GAF-S was 49.89 (SD = 11.92) and for GAF-F 50.10 (SD = 11.92). The total GAF score mean, based on lowest GAF-S or GAF-F value, was 47.27 (SD = 11.26). For mean values of the subjective measures divided by functional level and gender, see Table 1. A Pillai’s MANOVA (4 × 2 factorial design) was con- ducted with Social Function (very low, low, intermediate, higher) and Gender (men, women) as independent vari- ables, and consumers satisfaction (ConSat), global qual- ity of life (GQL), and perceived global distress (PGD) as dependent variables. The analysis revealed significant effects for Social Function (p < 0.001, Eta2 = 0.027, power > 0.99) and for Gender (p < 0.001, Eta2 = 0.008, power = 0.98). However, the analysis did not show a significant main effect for the interaction Social Func- tion × Gender (p = 0.273, Eta2 = 0.001, power = 0.62). Results from univariate F-tests regarding Social Func- tion and Gender are shown below. For means and stan- dard deviati ons see Table 1. Table 1. Means and (standard deviations) for social function (very low, low, intermediate, higher) and gender (men, women) in re- gard to consumer’s satisfaction (ConSat), global quality of lif e (G QL), and perceived global distress (PGD). Very low Low Intermediate Higher Men Women Men Women Men Women Men Women ConSat 70.78 (15.87) 70.03 (17.48) 73.35 (13.85) 75.53 (14.11) 75.96 (14.32) 78.05 (13.73) 78.90 (11.68) 81.63 (12.33) GQL 56.59 (27.90) 51.50 (30.27) 59.45 (24.91) 57.32 (25.43) 62.16 (21.95) 60.62 (24.59) 68.40 (20.66) 69.55 (21.11) PGD 57.79 (29.36) 50.65 (32.69) 60.45 (27.64) 55.89 (28.40) 67.29 (25.42) 62.08 (27.56) 70.80 (24.64) 72.53 (27.08)  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 92 3.1. Social Function Univariate F-tests showed significant effects for ConSat [F (3, 2544) = 42.19, p < 0.001], GQL [F (3, 2544) = 30.59, p < 0.001], and PDG [F (3, 2544) = 38.03, p < 0.001]. Post hoc testing (Tukey-HSD, 5% level) showed concerning ConSat significant effects between all the four groups according to a trend where the group with the higher function was the most satisfied with the care while the group with very low function was the least satisfied group. Similar pattern was found for GQL, where those with the best function scored more posi- tively while those with the worst function score more negatively (even though there were no significant effects in regard to the low and intermediate groups) and for PGD (even though there was no significant difference between the very low function group and the low func- tion group). Subsequently trend tests (Difference Cus- tom Hypothesis Tests, 5% level) confirmed significant trends for all dependent variables indicating that the hi- gher the social function, the higher would participants score on dependent variables. 3.2. Gender Univariate F-tests showed significant effects for ConSat [F (1, 2544) = 7.02, p = 0.008] and PGD [F (1, 2544) = 10.79, p = 0.001]. Descriptive analysis (Table 1) showed that women were more satisfied with the care but also more distressed as compared to men. 4. DISCUSSION The present study had two main results: (a) With in- creasing Social Function, as rated by professionals with the split-GAF-F scale, the better were patients’ Con- sumer Satisfaction, as well as their subjective Qu ality of Lif e an d P ercei v ed G lob a l D ist re ss ; (b ) Women, as a gr oup, were more satisfied with the care but also more dis- tressed as compared to men. 4.1. Differences in Subjective Dimensions According to Level of Social Functioning In this study si gnificant effects were found between all the four groups of Social function according to a trend where the group with the higher function was the most satisfied with the care while the group with very low function was the least satisfied group as measured with ConSat. We found no other studies describing associations between consumers satisfaction in relation to GAF-F apart from previous work from our group, where an Assertive Com- munity Treatment (ACT) based CM program was com- pared with best usual praxis showing improved ConSat and GAF-F scores (whereas GAF-S, symptoms severity, and split-GAF total did not improve) [10]. Studies using the original GAF together with other satisfaction scales targeting similar conceptual domains as ConSat provide some support to our findings, judged with caution considering the complexity of satisfaction construct [12]. For instance, in a study with schizoph- renia in a Swedish city an association between psychoso- cial functioning as measured by GAF and satisfaction with care was found, and its relationship with subjectiv e quality of life, sense of coheren ce, satisfaction with daily occupations, self-directedness, interviewer-rated quality of life, psychopathology, and psychosocial functioning [35]. A study in Japan found patients with higher satis- faction amongst generally-insured, mainly other then schizophrenia patients with higher GAF, whereas no correlation was found for the less satisfied mainly schi- zophrenia patients [36]. An evaluation of the Lambeth Early Onset team, found GAF associated with consumer satisfaction, attributable to satisfaction with staff man- ners, perceived competence, willingness to listen, type of service offered, and belief that the treatment “is right for me” [37]. In the present study a significant trend was found for Quality of Life indicating that the higher the social func- tion, based on GAF-F grouping, the higher would par- ticipants score on subjective quality of life, even though there were no significant effects in regard to the low and intermediate functioning groups in univariate F-tests. In a previous study in part of the cohort modest correlation between GAF-F and GQL was found (rho = 0.18) [23]. This is in line with previous research suggesting that these dimensions might be independent and should be assessed separately [38]. The only other study found concerning mainly schizo- phrenia patients using GAF-F and a quality of life meas- ure (Lehman Quality of Life scale), was a First-Episode Schizophrenia Scandinavian study, but no associative results were presented allowing comparison [39]. Stud- ies that described changes with other quality of life measures together with GAF-F changes, but in other patient groups, also give some support to the use of GAF-F for categorizing social functioning [40,41]. As mentioned in the instruments section, the GQL was developed from the corresponding item in MANSA and LQOLP, and GQL correlation with the initial item of MANSA, “Life as a whole” was rho = 0.86, with the MANSA-total sum rho = 0.66. With this in mind, find- ings in a study with schizophrenia patients at six sites within the UK that found a correlatio n between MANSA and GAF-F of r = 0.36 seems in line with the present study [42]. This fairly low correlation in the two studies can be assumed to indicate a relatively weak association and be a reason why there was no significant effects on GQL in regard to the low and intermediate functioning groups in univariate F-tests in the present study. This is not disappointin g. A modest association between qu ality Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 93 of life and social functioning on group level is precisely a reason why the Quality star network in cluded the GQL in its follow-up system, to be a remainder that in indi- vidual cases subjective quality of life may often be per- ceived as low though other measures are good, or vice versa. Thus, it should not be assumed that GAF-F social function ratings, as a rule, are strongly associated with subjective experience outcomes measures such as self- esteem or satisfaction with life [43]. In this study a significant trend for the perceived menta l distress, using the Perceived Global Distress scale, was found, indicating that the higher the social function, based on GAF-F grouping, the better would participants score on PGD, even though there was no significant ef- fects in regard to the “Very low” function group and the “Low” function group in univariate F-tests. In previous work it was shown that correlations between PGD and different subjective and objective measures varied but depressive features seemed to play an important role in patients’ construct of PGD [24]. The reliable use of GAF-F groupings for describing associations with distress also seems supported by re- ports by others in distress associated areas. Such reports are available regarding “Apathy” correlation with GAF- F [44,45]. SCL90R and GAF-F both improved following care at milieu therapeutic wards [41], a psychotherapeu- tic program with mainly borderline patients showed im- provements in GAF-F, and ratings on Target Complaint (TC), a measure to provide information about the three major complaints that led to seek treatment [40 ]. Reports of distress related measures between patient groups with parallel use of GAF-F and are also supportive. Such re- ports include a reports regarding “self-certainty” for bi- polar and schizophrenia patients [46], using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Beck Anxiety In- ventory (BAI) for schizophrenia and mood disorder pa- tient groups [47], narcissism using the Narcissistic Per- sonality Inventory (NPI-21), self-esteem and “self-be- liefs about ability to cope” using the Rosenberg Self- Esteem Scale (RSES) in acute ward patients [48], and results with The Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale in a milieu therap eutic wards study [41]. 4.2. Differences in Subjective Dimensions According to Gender A main result in this study was that women, as a group, were found more satisfied with the care but also more distressed as compared to men, whereas no difference was found regarding quality of life. The finding that women are more satisfied with the care than men is in line with other studies, for instance reported from Nor- wegian outpatient clinics within 33 health trusts [49], and from a psychiatric catchment area in south Rome, Italy [50]. However, yet other studies found no gender differences regarding satisfaction with care and service, for instance in the EPSILON project regarding schizo- phrenia in five European countries [ 51], an d a study with a community mental health team in North Yorkshire, England [52]. A pilot study by Nysam (A Swedish net- work for development of Key Figures) using the Quality Star instruments, report a ConSat mean of 75 with small variations between diagnoses but no significant differ- ences between men and women [53] . In a previous work in part of the present cohort it was found that women were significantly more satisfied than men with the provided care, according to scores on ConSat, during an entire six year period studied, than men, though both show ed increasing tendencies [2 5]. As no major differences in patient characteristics between genders were evident, it was hypothesized that service factors may be part of an explanation. The service deliv- ery model of most services participating in the Quality Start cooperation are devoted to case-management and ACT principles and several centers practices a developed form of shared decision making, in which the Quality Star method is integrated. The question was raised, if this program and service form may attract women more. The finding in this study that women, as a group, were more distressed, according to scores on the PGD scale, as compared to men, (whereas the opposite was the case for consumer satisfaction) is in line with finding in the mentioned Nysam study [53]. PGD self-ratings in the present study was 61.46, whereas the total mean in the Nysam study was in the range of 63 - 67 for psychosis patients (with women slightly more distressed than men), in contrast to means 57 - 32 in other diagnostic groups, where women were particularly more distressed in the affective disorder groups then men. In view of previously mentioned opinion that subject- tive measures tend to be largely influenced by mood [12] and that much of the feelings of being ill seems to be channeled via affective symptoms [54], the question could be raised if affective aspects of perceived distress are particularly detected with the PDG, as its construct was found strongly associated to depressive features [24]. Possibly women express more perceived distress am- ongst psychosis SMI patients through a depressive com- ponent. To clarify this further, it would be fit to, in the first place, explore this using MANSA, reported on item level, together with relevant variables, as PGD is derived from the last MANSA item “How satisfied are you with your mental health” for stand-alone use. Our literature search failed at this time to find such studies. A final finding in this study was that there was no dif- ference between men and women regarding perceived C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 94 quality of life, measured by the GQL scale. Similarly, the previously mentioned Nysam study found no sig- nificant difference in this regard [53]. This finding is in line with, for instance, a pooled analysis of 16 studies (using MANSA or LQOLP) to study factors influencing subjective quality of life in patients with schizophrenia and other mental disorders, where it was found that gender did not have an effect [55]. Likewise, using the LQOLP instrument, it was found in a study with schizo- phrenia patients in the Netherlands that gender was not related to general quality of life [5 6]. The referred works and others have elaborated on what other factors have major effect on quality of life. To clarify this further, it would, again, be fit to explore this using MANSA or LQOLP, reported on item level, together with relevant independent variables, as PGD is derived from the first MANSA item regarding satisfaction with “Life as a whole” for stand-alone use. 4.3. Limitations of the Study Although the fo ur groups of functiona l levels were suffi- cient to show variations in subjective measures in the cohort of serious mentally ill, it might have been of cer- tain interest to add subjective evaluations from patients below GAF-F 30 (where intensive care and service is often needed) and to add a separate analysis of the main diagnostic group of sch izophrenia in the material. 4.4. Final Remarks A secondary result comes out of the use in this study of the fairly new split-GAF Social Function subscale, GAF- F and its use for categorizing functioning into “Very Low” to “Higher” Social Function groups. Literature re- garding split-GAF use is still limited. A search for re- ports using this instrument revealed 32 articles citing the main methods article [20]. Summarizing, none of the studies were found with a patient groups similar to the cohort in the present work allowing direct comparisons. However, the descriptions found of GAF-F differences between patient groups, and, in some cases, changes over time are judged supportive to GAF-F reliability allowing its use to discriminate between group levels and justify our GAF-F based subdivision into “Very Low” to “Higher” Social Function groups. In the present study, there was a trend for all three subjective areas in our study, i.e. consumer satisfaction, subjective quality of life and perceived distress, to have higher ratings with increased levels of observed social function. It may intuitively seem plausible that the three subjective dimensions travel together in the same direc- tion. The first study question regarding differences in subjective measures depending on functional levels, thus got a positive answer, and, it may be added, this was possible to demonstrate with the global generic measures used. The second question, regarding the influence of gender differences was also verified. The combined ef- fect of functional level and gender on the patient subject- tive measures was however not shown on significant level. Bearing in mind that the study was carried out as a cross-sectional study and our familiarity with case-mix differences between centers and also reminding that, as exemplified from the literature in the preceding discus- sion, variations in levels of effects of gender and func- tional levels on different subjective measures has been noted by several researches, this result underline the importance of scrutinizing case-mix details before com- paring between p atien t groups or serv ices. As th e presen t cohort can be expected to be fairly representative for schizophrenia dominated SMI specialized psychiatric care in Sweden, it might be suggested to standardize materials regarding gender and functional levels before at all comparing centers regarding patient subjective out- comes. The questions must also be raised to what extent variations shown might be explained also by the con- structs of the measures used. For instance, the PGD may possibly be sensitive to “mood” elements, and it merits further studies to ascertain such aspects in comparison with other constructs. Other possible explanatory factors to the variations are for instance duration of illness, syn- drome severity, as well as service delivery elements, both in form and in contents. Further studies in the series of investigations with the Quality star cohort should ad- dress this, by adding such factors in group analyses. For the basic aim of the Quality Star, to be a tool to support dialogue with the individual patient, the result support the importance of talking though the situation in a multi-dimensional perspective as it is obvious that the general tendency that though subj ective meas ur es tend to “travel together” there is important individual variations in this sence. Thus, we do agree with for instance Prieb e et al. [57] in their suggestion that: “If one is to make use of subjective assessments for the planning and delivery of care and treatment one has to use different instru- ments.” In this sense The Quality star, with a balanced mix of user perceived and clinician ratings, is an out- come-informed model for a clinical management based on shared decision making. 5. CONCLUSIONS The main findings, that subj ective reports of satisfactio n, quality of life, and distress are more positive the better rated functioning, were in line with other studies. How- ever, the gender differences in these respects are in line with some, but not with other, studies. This poses ques- tions how patient factors, instrument constructs, and Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 95 treatment, especially shared decision making, influence subjective reports. Basic common variables in all these respects are needed in routine care to facilitate service comparisons. The Swedish “Quality star” initiative is an attempt to support development in this direction. The present study indicated that the used global measures could be sufficient for overview group comparisons, and supports that further efforts should be made to develop the model regarding routine reporting of needed vari- ables. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Authors acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Göran Eiman, RN, Ass. Head Psychiatric dept., Kungälv Hospital, Kungäl v in preparing the data base used. Our gratitude is also expressed to all users of the Quality Star method and their willingness to make their data available for this study. REFERENCES [1] Roeling, M.P. (2010) Functioning is the cornerstone of life. Journal of European Psychology Students, 2, 1-14. [2] Burns, T. and Patrick, D. (2007) Social functioning as an outcome measure in schizophrenia studies. Acta Psychi- atric Scand, 116, 403-418. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01108.x [3] Salloum, I.M. and Mezzich, J.E. (2009) Psychiatric di- agnosis: Challenges and prospects. Wiley-Blackwell, Ox- ford. [4] Regier, D.A., Narrow, W.E., Kuhl, E.A. and Kupfer, D.J. (2009) The conceptual development of DSM-V. Ameri can Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 645-650. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020279 [5] Flanagan, E.H., Davidson, L. and Strauss, J.S. (2010) The need for patient-subjective data in the dsm and the ICD. Psychiatry, 73, 297-307. doi:10.1521/psyc.2010.73.4.297 [6] Sörgaard, K.W., Heikkilä, J., Hansson, L., Vinding, H.R., Bjarnason, O., Bengtson-Tops, A., et al. (2002) Self-et- eem in persons with schizophrenia. A Nordic multicentre study. Journal of Mental Health, 11, 405-415. doi:10.1080/09638230020023769 [7] Mattsson, M., Lawoko, S., Cullberg, J., Olsson, U., Hansson, L. and Forsell, Y., (2005) Background factors as determinants of satisfaction with care among first- episode psychosis patients. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40, 749-754. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0945-7 [8] Ruggeri, M., Lasalvia, A., Bisoffi, G., Thomicroft, G., Vazquez-Barquerot, J.L., Becker, T., et al. (2003) Satis- faction with mental health services among people with schizo-phrenia in five european sites: Results from the epsilon study. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29, 229-245. [9] Helldin, L., Kane, J., Karilampi, U., Norlander, T. and Archer, T. (2008) Experience of quality of life and atti- tude to care and treatment in patients with schizophrenia: Role of cross-sectional remission. International Journal of Psychiatric Clinical Practice, 12, 97-104. doi:10.1080/13651500701660007 [10] Malm, U., Ivarsson, B., Allebeck, P. and Falloon, I.R.H. (2003) Integrated care in schizophrenia: A 2-year ran- domized controlled study of two community-based treat- ment programs. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 107, 415-423. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00085.x [11] Priebe, S., M cCa be, R., Bullenkamp, J., Hansson, L., Laub er, C., Martinez-Leal, R., et al. (2007) Structured patient clini- cian communication and 1-year outcome in community mental healthcare: Cluster randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, 420-426. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036939 [12] McCabe, R., Saidi, M. and Priebe, S. (2007) Patient-re- ported outcomes in schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, 21-28. doi:10.1192/bjp.191.50.s21 [13] Hafner, H. (2003) Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28, 17-54. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00125-7 [14] Nasser, E.H., Walders, N. and Jenkins, J.H. (2002) The experience of schizophrenia: What’s gender got to do with it? A critical review of the current status of research on schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 28, 351-362. [15] Erdner, L. and Ivarsson, B. (2002) The quality star—A tool for regular outcome monitoring. Cambridge, UK, 65-69. [16] Ivarsson, B., Erdner, L. and Malm, U. (2006) The quality star—An algorithm for the evaluation of mental health services. Presentation for ENMESH conference, Lund, Sweden 10 June, URL (last checked 21 March 2011) http://www.kvalitetsstjarnan.se/Rapporter/THE%20QUA LITY%20STAR%20060610.pdf [17] Burns, T. and Firn, M. (2002) Assertive outreach in men- tal health, a manual for practitioners. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [18] Malm, U. (2002) Case management, studentlitteratur. Lund, Sweden . [19] Falloon, I.R.H., Montero, I., Sungur, M., Mastroeni, A., Malm, U., Economou, M., et al. (2004) Implementation of evidence-based treatment for schizophrenic disorders: Two-year outcome of an international field trial of opti- mal treatment. World Psychiatry, 3, 104-109. [20] Pedersen, G., Hagtvet, K.A. and Karterud, S. (2007) Gen- eralizability studies of the global assessment of function- ing—split version. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48, 88-94, 2007. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.03.008 [21] Hjärthag, F., Helldin, L. and Norlander, T. (2008) Family burden: Psychometric properties of the burden inventory for relatives to persons with psychotic disturbance. Psy- chological Reports, 103, 323-335. [22] Ivarsson, B. and Malm, U. (2007) Self-reported consumer satisfaction in mental health services: Validation of a self-rating version of the UKU-consumer satisfaction rating scale. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 61, 194-200. doi:10.1080/08039480701352488 [23] Ivarsson, B., Malm, U., Lindström, L. and Norlander, T. (2010) The self-assessment global quality of life scale— Reliability and construct validity. International Journal of Psychiatric Clinical Practice, 14, 287-297. doi:10.3109/13651501.2010.487217 [24] Ivarsson, B., Lindström, L., Malm, U. and Norlander, T. (2011) The self-assessment perceived global distress scale—Reliability and construct validity. Psychology, 2, 283-290. doi:10.4236/psych.2011.24045 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 96 [25] Nordén, T., Ivarsson, B., Malm, U. and Norlander, T. (2011) Gender and treatment comparisons: Consumer satisfaction, quality of life, function and symptoms in a cohort of patients with psychiatric diagnoses. Social Be- havior and Personality, 39, 1037-1086. doi:10.2224/sbp.2011.39.8.1073 [26] Everitt, B.S. and Wykes, T. (1999) A dictionary for statis- tics for psychologists. Arnold, London. [27] GGG manual and instruments (2009) GGG-group of the quality star network. instruments and manual, original Swedish version. URL (last checked 21 March 2011), present English version published by Karlstad university in cooperation with the Quality Star Network. Available through authors. http://www.kvalitetsstjarnan.se/Blanketter/SVENSKA/M anual%202009-09-28.doc [28] APA (American Psychiatric Association). (2002) Diag- nostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR). American Psychiat- ric Press, Washington, DC. [29] Patterson, D.A. and Lee, M.S. (1995) Field trial of the global assessment of functioning scale-modified. Am- erican Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 1386-1388. [30] Yamauchi, K., Ono, Y., Baba, K. and Ikegami, N. (2001) The actual process of rating the global assessment of functioning scale. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 42, 403- 409. doi:10.1053/comp.2001.26268 [31] Söderberg, P. and Tungström, S. (2007) Outcome in psy- chiatric outpatient services. Reliability, validity and out- come based on routine assessments with the GAF scale. Umeå: Department of Psychology, Umeå University, Swe- den. [32] Aas, I.H.M. (2010) Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF): Properties and frontier of current knowledge. Annals of General Psychiatry, 9, 20. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-9-20 [33] Aas, I.H.M. (2011) Guidelines for rating Global Assess- ment of Functioning (GAF). Annals of General Psychia- try, 10, 2. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-10-2 [34] Duncan, B.L., Miller, S.D., Wampold, B.E. and Hubble, M.A. (2009) The heart and soul o f change, second edition: Delivering what works in therapy. American Psychological Association, Washington DC. [35] Eklund, M. and Hansson, L. (2001) Determinants of satisfaction with community-based psychiatric services: A cross-sectional study among schizophrenia outpatients. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 55, 413-418. doi:10.1080/08039480152693318 [36] Ito, H. and Sederer, L.I. (2001) Are publicly-insured psychiatric outpatients in Japan satisfied? Health Policy, 56, 205-213. doi:10.1016/S0168-8510(01)00116-6 [37] Garety, P.A., Craig, T.K.J., Dunn, G., Fornells-Ambrojo, M., Colbert, S., Rahaman, N., et al. (2006) Specialised care for early psychosis: Symptoms, social functioning and patient satisfaction, randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188, 37-45. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007286 [38] Brissos, S., Balanza´-Martinez, V., Videira, D.V., Carita, A.I. and Figueira, M.L. (2011) Is personal and social functioning associated with subjective quality of life in schizophrenia patients living in the community? Eu rope Arch Psychiatry Clinical Neuroscience, Published on-line 08 March 2011. doi:10.1007/s00406-011-0200-z [39] Melle, I., Larsen, T.K., Haahr, U., Friis, S., Johannesen, J.O., Opjordsmoen, S., Rund, B.R., Simonsen, E., Vaglum, P. and McGlashan, T. (2008) Prevention of negative sym- ptom psychopathologies in first-episode schizophrenia. Two-y ear effects of reducing the duration of untreated psy- chosis. Ar ch General Psychiatry, 65, 634-640. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.634 [40] Petersen, B., Toft, J., Christensen, N.B., Foldager, L., Munk- Jörgensen, P., Lien, K., et al. (2008) Outcome of a psy- chotherapeutic programme for patients with severe per- sonality disorders. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 62, 450- 456. doi:10.1080/08039480801984271 [41] Jörgensen, K.N., Römma, V. and Rumdmo, T. (2009) Asso- ciations between ward atmosphere, patient satisfaction and outcome. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16, 113-120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01333.x [42] Kusel, Y., Laugharne, R. , Perrington, S., McKendri ck, J., Stephenson, D., Stockton-Henderson, J., et al. (2007) Measurement of quality of life in schizophrenia: A com- parison of two scales. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epi- demiolgdy, 42, 819-823. doi:10.1007/s00127-007-0249-1 [43] Brekke, J.S. and Long, J.D. (2000) Community-based psychosocial rehabilitation and prospective change in functional, clinical, and subjective experience variables in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 26, 667-680. [44] Faerden, A., Friis, S., Agartz, I., Barrett, E. A., Nesvåg, R. and Finset, A., et al. (2009) Apathy and functioning in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 60, 1495- 1503. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.11.1495 [45] Faerden, A., Finset, A., Friis, S., Agartz, I., Barrett, E.A., Nesvåg, R., et al. (2010) Apathy in first episode psycho- sis patients: One year follow up. Schizophrenia Research, 116, 20-26. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.014 [46] Engh, J.A., Friis, S., Birkenaes, A.B., Jónsdóttir, H., Klungsøyr, O., Ringen, P.A., et al. (2010) Delusions are associated with poor cognitive insight in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36, 830-835. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn193 [47] Lykke, J., Hesse, M., Austin, S.F. and Oestrich, I. (2008) Validity of the BPRS, the BDI and the BAI in dual diag- nosis patients. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 292-300. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.020 [48] Svindseth, M.F., Nøttestad, J.A., Wallin, J., Roaldset, J.O. and Dahl, A.A. (2008) Narcissism in patients admitted to psychiatric acute wards: Its relation to violence, suicidal- ity and other psychopathology. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 13. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-13 [49] Bjørngaard, J.H., Ruud, T., Garratt, A. and Hatling, T. (2007) Patients ‘experiences and clinicians’ ratings of the quality of outpatient teams in psychiatric care units in Norway. Psychiatric Services, 58, 1102-1107. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.58.8.1102 [50] Gigantescoa, A., Picardia, A., Chiaiab, E., Balbib, A. and Morosini, P. (2002) Patients’ and relatives’ satisfaction with psychiatric services in a large catchment area in Rome. European Psychiatry, 17, 139-147. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(02)00643-0 [51] Thornicroft, G., Leese, M., Tansella, M., Howard, L., Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  B. Ivarsson et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 88-97 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 97 OJPsych Toulmin, H., Herran, A., et al. (2002) Gender differ- ences in living with schizophrenia, a cross-sectional European multi-site study. Schizophrenia Research, 57, 191-200. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00318-8 [52] Blenkiron, P. and Hammill, C.A. (2003) What determines patients’ satisfaction with their mental health care and quality of life? Postgraduate Medical Journal, 79, 337- 340.doi:10.1136/pmj.79.932.337 [53] Eiman, G. and Ivarsson, B. (2011) Prövning av kvali- etsstjärnan inom nysam GAF-project 2002-2004, “Quality Star Test within the nysam GAF project 2002-2004,” Ny- sam Adult Psychiatry Development Group, 2004. URL (last checked 21 March 2011) http://www.kvalitetsstjarnan.se/Nysam%20GAF/09A%2 0Rapport%20KvalStj%2002%2004.pdf [54] Lindström, E., Jedenius, E. and Levander, S. (2009) A symptom self-rating scale for schizophrenia (4S): Psy- chometric properties, reliability and validity. Nordic Jour- nal Psychiatry, 63, 368-374. doi:10.1080/08039480902807298 [55] Priebe, S., Reininghaus, U., McCabe, R., Burns, T., Ek- lund, M., Hansson, L., et al. (2010) Factors influencing subjective quality of life in patients with schizophrenia and other mental disorders: A pooled analysis. Schizo- phrenia Research, 121, 251-258. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.020 [56] Meijer, C.J., Koeter, M.W.J., Sprangers, M.A.G. and Schene, A.H. (2009) Predictors of general quality of life and the mediating role of health related quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry Psychiat- ric Epidemiology, 44, 361-368. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0448-4 [57] Priebe, S., Kaiser, W., Huxley, P., Röder-Wanner, U.-U. and Rudolf, H. (1998) Do different subjective evaluation criteria reflect distinct constructs? Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 186, 385-392. doi:10.1097/00005053-199807000-00001

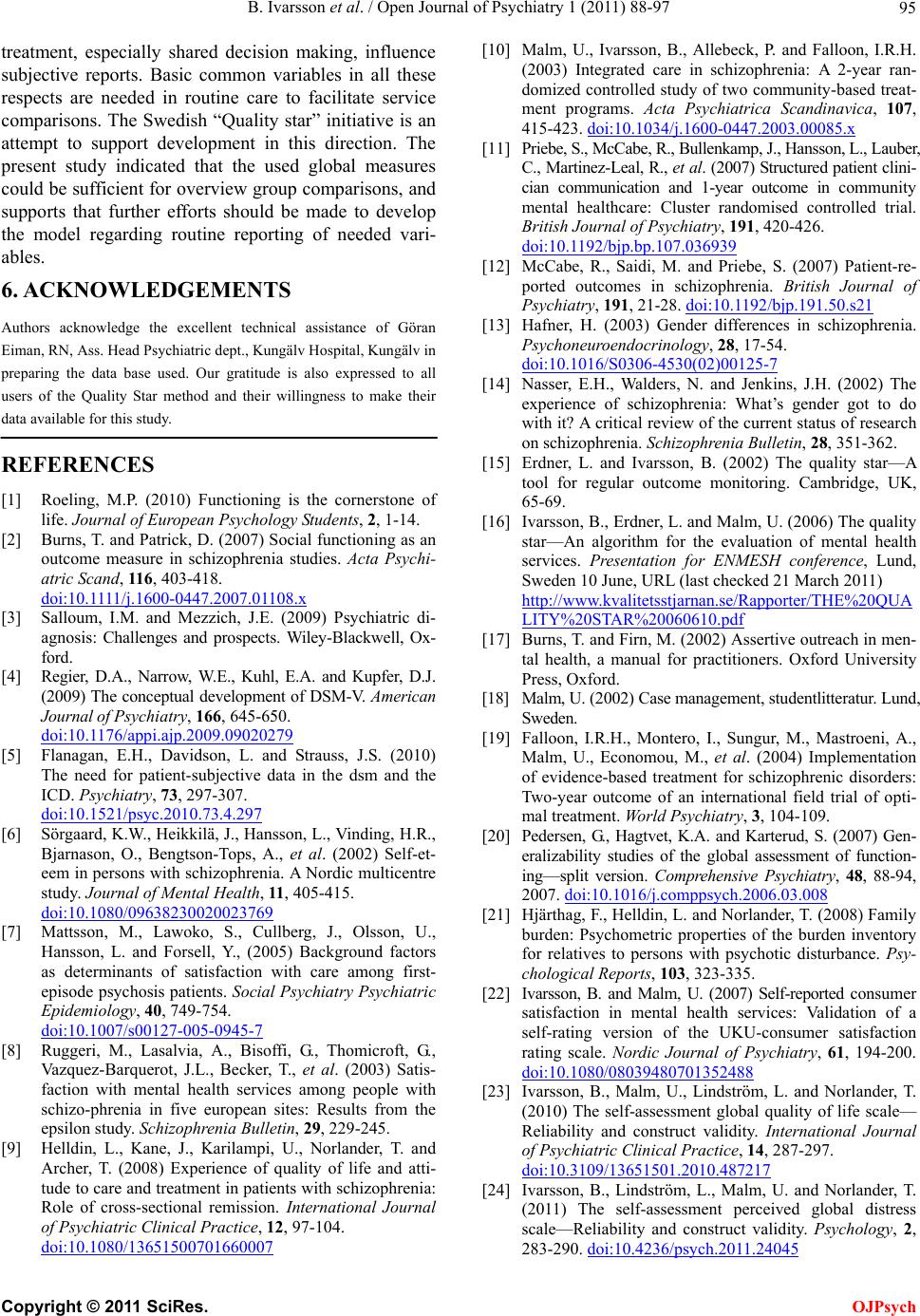

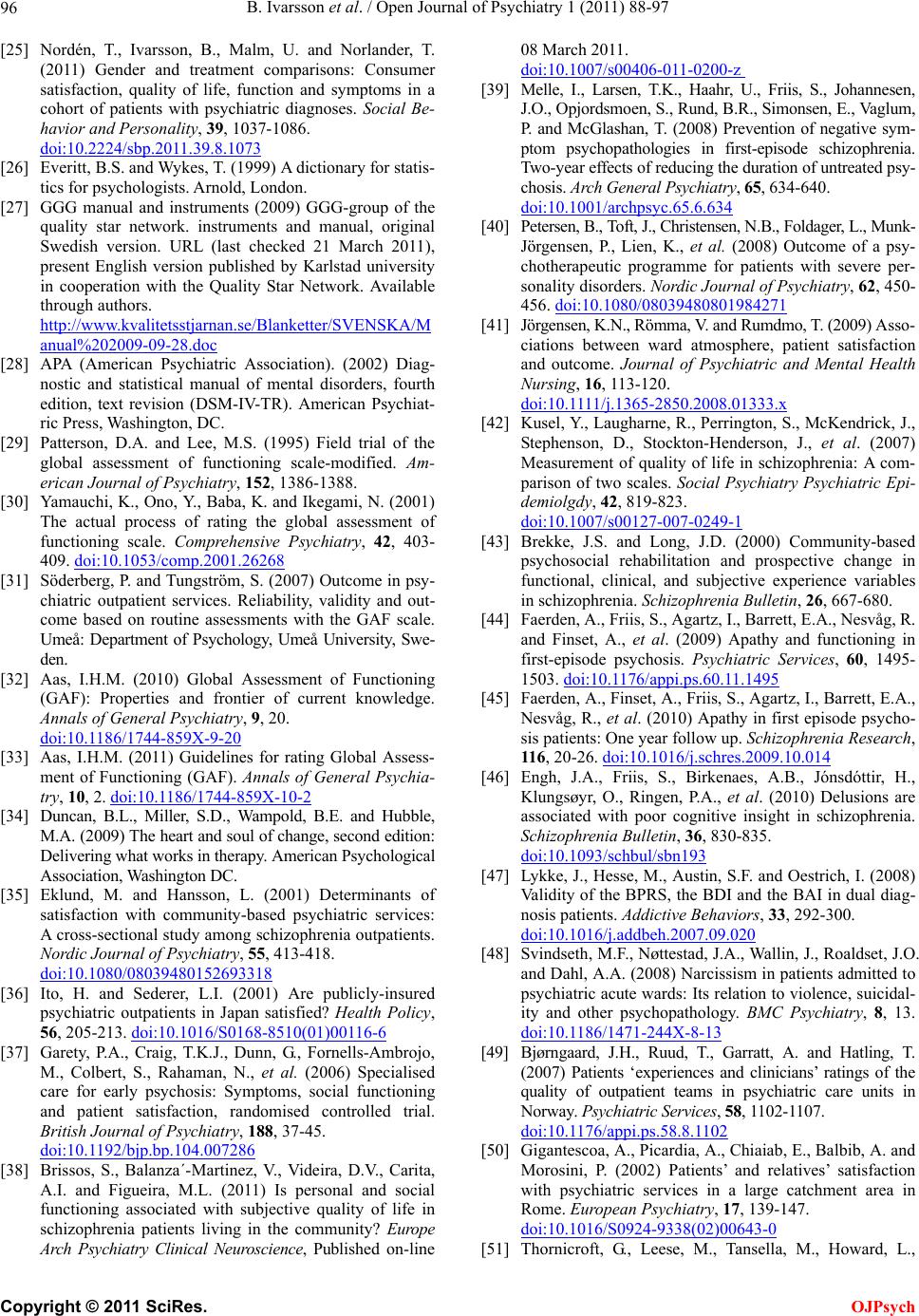

|