Open Journal of Psychiatry, 2011, 1, 79-87 doi:10.4236/jsemat.2011.13012 Published Online October 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJPsych/ OJPsych ). Published Online October 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPsych Extended time improves reading comprehension test scores for adolescents with ADHD Thomas Edwards Brown*, Philipp Christian Reichel, Donald Michael Quinlan Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, USA. Email: *thomas.e.brown@yale.edu Received 29 August 2011; revised 20 September 2011; accepted 15 October 2011. ABSTRACT Objective: To test the hypotheses that reading com- prehension difficulties of adolescent students with ADHD: 1) are related not so much to weak verbal abilities or weak basic reading skills, as to impair- ments of working memory and processing speed characteristic of ADHD; and 2) that extended time on a test of reading comprehension would yield signifi- cantly higher reading comprehension scores than would standard time. Method: Charts of 145 adoles- cents 13 - 18 years diagnosed with DSM-IV ADHD and no specific reading disorder after a comprehen- sive clinical and psycho-educational evaluation, were reviewed to extract 1) word reading and word attack subtest scores from the Woodcock-Johnson Achieve- ment Test or the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test; 2) Index scores from WISC-IV or WAIS-III IQ tests; 3) scores from the Nelson-Denny Reading Test. Results: Mean index scores for verbal comprehension abilities not including reading were in the high aver- age range, but working memory and processing speed index scores were significantly weaker. Under standard time limits 53% were unable to complete the reading comprehension test and only 42.8% were able to score within 1 SD of their IQ verbal compre- hension index (VCI). When allowed extended time, 77.9% were able to score within 1 SD of their VCI. T-test comparisons between standard time and ex- tended time were significant at <0.001. Conclusions: Allowing extended time for adolescents with ADHD to complete tests involving reading may help to com- pensate for their impairments of working memory and processing speed, allowing them to score closer to their actual verbal abilities. Keywords: ADHD; Reading Comprehension; Extended Time; Working Memory; Processing Speed 1. INTRODUCTION Among adolescents with ADHD are some who report chronic difficulties in reading that significantly impair their ability to complete tests and assignments within usual time allotments. Although most demonstrate no significant impairment in phonological processing, the usual hallmark of dyslexia, these students complain of chronic slowness in assigned reading, due usually to a need to re-read passages several times in order fully to grasp the meaning. They also report that, though they may understand the content at the time of reading a pas- sage, they have chronic difficulty in recalling what they have read just a few minutes earlier. It appears that re-reading is needed to engage their focus sufficiently to encode the information in memory. One student with ADHD described this: “Most of the time when I’m read- ing assignments in my textbooks, I’m just licking the words rather than chewing them. That’s why I have to keep going back to read it all over again.” Interestingly, many of these students report that such impairments often are not present when reading self- chosen rather than assigned texts. This clinical observa- tion suggests that such reading impairments may be the result of impairments in executive functions (EF), which tend to be situationally specific, rather than consistent impairment in verbal abilities or basic reading skills. Pennington [1] and Brown [2,3] have described the situ- ational variability of executive functions impaired in ADHD, how individuals with ADHD often demonstrate little impairment in their ability to deploy executive functions when doing tasks which hold strong personal interest or anxiety for them, though they show much EF impairment in most other situations. This is consistent with findings by Anmarkrud and Braten [4] that stu- dents’ motivation for reading content of personal interest to them, the value they place on reading a specific text, plays an important role in their reading comprehension. In this study, we hypothesized that adolescents with  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 79-87 80 ADHD who are slow in reading comprehension tasks and do not have a specific learning disability in reading would demonstrate relative weaknesses in working mem- ory and processing speed, aspects of executive function often impaired in ADHD. Further, we hypothesized that extended time on a test of reading vocabulary and read- ing comprehension would help these students to com- pensate for their ADHD-related reading impairments, yielding higher reading comprehension scores more con- sistent with the individual’s verbal comprehension abili- ties as shown on an IQ measure not involving reading. There is considerable evidence that executive func- tions often impaired in ADHD, especially processing speed and working memory, play an important role in reading, particularly in reading fluency and comprehen- sion (see Willcutt [5], Shanahan [6], Laasonen [7], McGrath [8], Arnell [9] and Swanson [10]). This is true not only in those with a reading disorder, but also in those who are not impaired in phonological processing (see: Sesma [11], Locasio [12], Samuelson [13], Jacob- son [14], Bental [15] and Leong [16]). One specific executive function important in reading comprehension is processing speed. Willcutt et al. [17] demonstrated that impairment in processing speed is found much more in children with reading disability (dyslexia), in children with ADHD, and in those with both disorders than in controls. In a sample of children and adolescents Shanahan et al. [6] demonstrated that processing speed, measured in multiple ways, is a shared cognitive risk factor across reading disorder and ADHD with a correlation of 0.7 between the two disorders. The authors suggested that participants with each disorder may be slowed down because they are engaging in a speed-accuracy trade-off, buying increased accuracy with a slower rate. The study by Shanahan et al. utilized a variety of measures to assess processing speed. These included linguistic measures such as rapid automatized naming (RAN) and the Stroop test as well as non-linguistic mea- sures such as the WISC Coding subtest, the Trailmaking test and the Stop-Signal task. Findings indicated that, despite their differences, these various measures of pro- cessing speed were highly correlated with one another, all apparently reflecting a common factor that contrib- utes to both ADHD and Reading Disorder. Similar findings in a sample of adults in Finland were reported by Laasonen, Leppamaki, Tani and Hokkanen [7]. Their assessments of adults with dyslexia, attention deficit disorder, and comorbid ADHD with dyslexia found that all shared relative weakness in processing speed as measured by the WAIS-III. Primary importance of processing speed in overlap between ADHD and reading disorder was also demons- trated in a study by McGrath et al. [8]. They used multi- ple deficit modeling with a sample of children with ADHD and/or Reading Disorder. Their analysis identi- fied processing speed as the most important common factor between inattention and reading. One measure of processing speed is the rapid automa- tized naming (RAN) test, a timed measure of speed and accuracy for naming familiar stimuli, e.g letters, digits, colors, etc. randomly sequenced. The RAN has been shown in numerous studies to predict reading compre- hension. Arnell and colleagues [9] recently reported a study using a sample of university undergraduates that identified specific cognitive elements of the RAN that contribute to its shared variance with reading compre- hension. Their various measures explained 52% of the variance shared by the RAN and reading comprehension as measured by the Nelson-Denney Reading Test (NDRT). Results suggested that working memory encoding is a significant component of the relationship between proc- essing speed measured by the RAN and reading ability. Both processing speed and working memory have been identified as important aspects of the complex cog- nitive processes involved in reading comprehension. Cain and Oakhill [18] reviewed multiple studies which demonstrate that for skilled readers as well as for those with poor reading skills or very limited reading compre- hension, working memory plays a critical role in inte- grating information to facilitate comprehension of text. This is likely to be because comprehension depends upon recalling what has been read in preceding sentences and paragraphs so that the reader can develop and modify an adequate working understanding of the message of each section of the text and of how those components are re- lated to one another. Swanson, Zheng and Jerman [10] published a meta- analysis of studies on working memory (WM), short- term memory (STM) and reading disabilities. They de- fined WM as “a processing resource of limited capacity involved in the preservation of information while proc- essing the same or other information (p. 260)”; they dif- ferentiated this from STM, a resource in which small amounts of information are held passively and then pro- duced in an untransformed fashion, like the buffer of a printer holding information from a computer prior to printing. They noted that WM measures in these studies were related primarily to reading comprehension of sen- tences and paragraphs while STM measures related pri- marily to recognition of individual words on a list. Sesma, Mahone and colleagues [11] extended this view in a 2009 study, noting that while some children have dif- ficulty with reading comprehension because they have chronic difficulty in decoding and accurately reading sin- gle words, there are others who struggle with reading Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 79-87 81 comprehension despite their having adequate ability to decode and accurately read single words. These re- searchers did a study with 60 children aged 9 to 15 years with deficits in reading comprehension to test the hy- pothesis that executive functions would be significantly associated with reading comprehension skills, but not with single word reading accuracy in children with word reading deficits, reading comprehension deficits, and/or ADHD. Results indicated that executive skills differentially support reading comprehension, but are less necessary for single word reading. They explained their findings as follows: “Reading comprehension is inherently more complex than single word reading, with demands that go beyond phonological decoding and word identification and include higher order cognitive processing of mean- ing conveyed through sentences and paragraphs… ex- ecutive control skills such as planning and working memory become more necessary as the length and com- plexity of written text increases” (p. 8). A subsequent study by these authors [12] of executive function im- pairments in children with reading comprehension defi- cits provided additional evidence that executive function impairments, including planning and organizing, were closely associated with impairments in reading compre- hension. A significant proportion of the samples in both of these studies were diagnosed with ADHD. Similar findings about the role of executive function impairments in reading comprehension of individuals with ADHD was reported by Samuelsson, Lundberg and Herkner [13]. In their study of male adults they found a significant correlation between poor reading compre- hendsion and ADHD while there was no significant as- sociation between word decoding and ADHD. They ex- plained this by arguing that word decoding “is deter- mined by a smoothly operating, encapsulated… phono- logical module largely unrelated to higher cognitive func- tions such as executive controls” while “reading compre- hension involves many of the higher cognitive control functions assumed to be impaired in ADHD” (p. 165). In a sample of 9 to 14 year old children with ADHD Ja- cobson, et al. [14] (2011) demonstrated that both proc- essing speed and working memory were significantly associated with reading fluency. The importance of working memory and processing speed in reading comprehension is not limited to reading in the English language. Using Hebrew language meas- ures, Bental and Tirosh [15] evaluated a sample of Israeli boys with ADHD only, Reading Disorder only, comorbid ADHD + Reading Disorder, and controls, all of whom were equivalent in oral language functions. They dem- onstrated that reading performance in Hebrew by pre- adolescent children with ADHD is linked to rapid nam- ing and to executive functions, particularly verbal work- ing memory, more than to phonological processing. A large sample of preadolescent Chinese children showed a similar pattern in a study by Leong, et al. [16] who found that verbal working memory had a strong unique effect on Chinese text comprehension, significantly gr- eater than the influence of their ability to read pseudo- words or rapid automatized naming (RAN). Increasing recognition of the importance of working memory and processing speed in reading comprehension is consistent with a major shift emerging from research on dyslexia. Shaywitz and Shaywitz [19] have empha- sized how current research shows that reading is not simply a modular process dependent only on phonologi- cal processing needed to decode words. They argued that reading must now be understood as involving also atten- tional mechanisms that are essential to fluency and automaticity in reading. “The critical requirement for automaticity is for the reader to encode the relevant items in memory and to retrieve them on a subsequent encounter… for both encoding and retrieval, attention is central (p. 1332).” The Shaywitz paper also notes the importance of high- er association cortices, particularly the prefrontal cortex, in attentional mechanisms. Recognizing that “… atten- tional mechanisms play a critical role in reading and that disruption of attentional mechanisms plays a causal role in reading difficulties (p. 1343)”, Shaywitz and Shaywitz suggested that medications shown effective for improve- ing attentional function in patients with ADHD “… might be an effective adjunct to improving reading in dyslexic students (p. 1329).” They also noted that “… lack of automatic, fluent reading means that the dyslexic reader may be able to decode words, but is still not able to read quickly and continues to be at a disadvantage compared to non-dyslexic peers when taking high-stakes standardized tests such as SATs, Graduate Management Admission Tests, Graduate Record Examination and so forth (p. 1343).” The comments of Shaywitz and Shaywitz focus on dyslexic readers, but they are applicable to non-dyslexic readers as well. Recent research such as studies cited earlier in this paper clearly indicates that adequate read- ing comprehension depends not only on ability to recog- nize and decode words. It also depends upon 1) adequate attention; 2) adequate working memory; and 3) adequate processing speed. Typically, individuals with ADHD are significantly impaired in all 3 of these critical executive functions. One example is a study of fluency and reading comprehension by Jacobson and colleagues [14] which demonstrated that slow processing speed and impaired working memory were significant predictors of difficult- ties in reading fluency in children aged 9 to 14 years C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 79-87 82 with ADHD. Our study reported here focused not on students who suffer from dyslexia, but a sample of adolescents aged 13 to 18 years who did not suffer from a reading disorder. This is an older group than those in most studies of reading comprehension, an age group whose academic work usually requires reading of longer, more complex texts. All had been carefully diagnosed with ADHD and were without a comorbid reading disorder. Students with scores for basic reading skills below the low average range were excluded from the study. We tested several predictions about cognitive functions related to reading comprehension difficulties in these adolescent students diagnosed with ADHD. We also tested the effects of one specific compensatory strategy that may be helpful to many of these students… extended time for a reading comprehension test. Walczyk and colleagues [20] have reported research testing a variety of compensatory strategies that have been demonstrated helpful for readers at various skill levels who are struggling for efficient comprehension of a text. These compensatory strategies include slowing down the reading rate; pausing to allow more time for processing; looking back in the text to clarify confusion; jumping over text segments that are confusing, but not essential; and rereading of the text to enhance under- standing. Regression analyses in their study revealed that restriction of time to read a text tends to reduce compre- hension because it does not allow sufficient opportunity for the reader to clarify information to be processed in working memory. This is consistent with clinical reports of many students with ADHD who are unable to com- plete exams within standard time allocation. Extended time is one useful way to help students whose reading comprehension is compromised by impaired working memory and processing speed. We predicted that students diagnosed with ADHD would tend to be significantly weaker in working mem- ory and processing speed than in their overall verbal abilities exclusive of reading. This prediction was con- sistent with findings of our study on executive function impairments in children and adolescents with ADHD. It was also consistent with findings reported by Mayes and Calhoun [21] in their report of IQ index score predictors of academic achievement. Their study used index scores from WISC-III/IV to predict learning disorders (LD) with a discrepancy formula using the Wechsler Individ- ual Achievement Test-Second Edition (WIAT-II). From a large sample of youths 6 - 16 yrs they reported that the most powerful predictor of academic achievement was the Verbal Comprehension Index and that the most pow- erful predictors of LD were the index score for Working Memory/Freedom from Distractibility and the index score for Processing Speed. We also predicted that our sample of students with ADHD and without a specific LD in reading would have relatively unimpaired basic reading skills (within 1 SD of their verbal comprehension index on the WISC/ WAIS) but would tend to score relatively low on a timed test of reading comprehension (≥1 SD below their ver- bal comprehension index). When allowed extended time on a reading comprehension test, we predicted that their score would be closer to their VCI. 2. METHODS 2.1. Sample Records of two ADHD specialty clinics in a metropolis- tan area of the Northeast U.S., one private, the other in a university medical center were reviewed to select charts of all individuals 13 to 18 years who sought consultation for attention or learning problems, met DSM-IV diag- nostic criteria for ADHD, had undergone a full psy- cho-educational evaluation within the past three years, and did not have any specific learning disorder in read- ing. Potential participants were excluded if their basic reading skills as measured by WIAT-II or WJ-III word reading or pseudoword decoding (word attack) scores were below 80, or if their vcrbal comprehension index score on the WISC or WAIS was below 80. Thus par- ticipants were all non-dyslexic students with verbal comprehension abilities (not including reading) in the low average range to superior range who suffered sig- nificant current impairments from ADHD sufficient to warrant diagnosis under DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. The sample included 145 participants aged 13 to 18 years; 69.1% were males. The mean for VCI was 118.6; the mean for POI was 112.6. Evaluation protocols in both clinics were identical. A licensed clinical psychologist experienced in assessing ADHD and related disorders conducted a two hour clinical interview of the patient with one or both parents to take relevant history and assess impairment according to DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD. A normed and validated rating scale for ADD and related executive functions, the Brown ADD Rating Scale, [22,23] was administered and screening for possible comorbid dis- orders was completed. In a separate session after ADHD diagnosis, the full WISC-IV [24] or WAIS-III [25] IQ tests were administered followed by the Wechsler Indi- vidual Achievement Test (WIAT-II) [26] or the Wood- cock-Johnson 3rd Edition Achievement Tests [27]. 2.2. Measures To assess basic reading skills, we used standardized measures of word reading and pseudoword reading (word attack) from the Woodcock-Johnson Achievement Test Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 79-87 83 (WJ-III) or the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test (WIAT-II). These were compared with the student’s overall verbal abilities as measured by the Verbal Com- prehension Index (VCI) of the student’s WISC or WAIS IQ tests, a measure of verbal ability not requiring read- ing. The VCI was used as a basis for comparison be- cause it is a validated and normed measure of verbal comprehension abilities that does not require any read- ing. To assess processing speed and working memory, we used two index scores from the student’s WISC or WAIS: Working Memory Index (WMI) and Processing Speed Index (PSI), neither of which involves reading, Mayes and colleagues [28] have shown, in their own research and have cited other studies showing that children with ADHD tend to score significantly lower on WMI and PSI than comparison children and significantly lower than their own Verbal Comprehension index. To assess the impact of extended time for reading comprehension, we used the Nelson-Denny Reading Test [NDRT] [29], a normed measure which requires each subject to complete 80 multiple choice vocabulary ques- tions within 15 min. Each is then asked to read 7 narra- tive passages and answer 38 multiple choice compre- hendsion questions within 20 min. Any individual unable to complete the vocabulary section is allowed up to 9 ad- ditional minutes; anyone unable to complete the com- prehension section is allowed up to 12 additional minutes. 2.3. Data Analysis To allow for comparison of NDRT and WAIS/WISC scores, the percentile ranks of the NDRT were converted to a normal-curve scale that matched the mean (100) and SD (15) of IQ and Index scores. We scored results ob- tained with extended time using the NDRT norms for standard time. Our procedure differs from the Extended Time tables used in the NDRT, but our procedure with this scoring is similar to that of Ofiesh, et al. [30] and closely mirrors what is done when the accommodation of extended time is allowed, i.e., scores are ranked on the same metric. Students given extended time accom- modations for standardized measures such as the SAT and ACT are scored on the same metric as students without accommodations. They are not penalized by be- ing scored with separate norms applicable only to those receiving extended time. We compared each student’s scores for reading vo- cabulary and reading comprehension on the NDRT under both standard time and extended time conditions (using the NDRT norms for standard time) with their basic reading abilities and their overall cognitive abilities as measured by the VCI. We then used paired t-tests to as- sess significance. We chose the verbal comprehension index as the standard for comparison because it is an age-based and validated measure of verbal comprehension abilities that does not require any reading. Normative data from the WIAT-II show that VCI is a reasonable predictor of reading comprehension. Only 11% - 12% of individu- als score more than 1 standard deviation below their WISC/WAIS VCI on a standardized measure of read- ing comprehension [26]. 3. RESULTS Overall verbal skills of these students on tests not in- volving reading were relatively strong. As shown in Figure 1, their WISC-IV/ WAIS-III Ver- bal Comprehension Index (VCI) mean was in the high average range: 118.6 (13.8). As predicted, and as is com- mon among individuals diagnosed with ADHD, their mean index scores for Working Memory (WMI) and Processing Speed (PSI) were both more than 1 SD lower, in the average range: WMI: 102.8 (14.2); PSI: 99.9 (16.3). These scores indicate relative weakness in these two index scores that tap executive functions associated with ADHD and are significantly lower than the VCI (p = < 0.0001). It should be noted that this sample was not strong only in verbal comprehension and weak in all other factors of measured IQ. Their mean score for Perceptual Organiza- tion Index (POI) was in the high average range, 112.6 (12.6), just 6 points lower than their mean VCI. This dis- crepancy is not significantly different from the stan- dardization samples for the WISC-IV or WAIS-III [26]. These students were in the high average range for the two factors of Wechsler IQ tests less sensitive to im- pairments of executive function. Like most individuals with ADHD, they were relatively weak in their scores for WMI and PSI, the two factors of these IQ tests that are more sensitive to executive function impairments [21]. Also shown in Figure 1 are mean scores for basic Figure 1. Basic reading vs. IQ verbal abilities vs. executive functions. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 79-87 84 reading skills on the WJ-III/WIAT-II, word recognition and word attack, which were solidly in the average range: word recognition: 106.5 (11.05) word attack: 106.8 (13.4). These scores indicate that basic reading skills of this sample were somewhat lower than their VCI, but still solidly in the average range. Reading difficulties of this group were not due to significant impairments in ability to use phonics principles to decode unfamiliar words or to impairments in ability to recognize and cor- rectly pronounce words from an age-appropriate vo- cabulary list. This is consistent with the findings of other studies (see: Sesma [11], Locasio [12] and Jacobson [14]) dem- onstrating that problems with reading comprehension exist independently in some students with fully adequate basic reading skills. Reading comprehension problems are not limited to those with weak decoding and/or sight vocabulary. Reading comprehension requires adequate decoding skills, but it also requires adequate executive functioning, especially in working memory and process- ing speed, two areas typically weak in individuals with ADHD. Figure 2 displays comparisons of participants’ mean scores for VCI and their mean scores for the NDRT un- der standard and extended time. Scores for the vocabu- lary section with standard time were 10.6 (15.1) points below their VCI. When those who were unable to finish the vocabulary section were allowed extended time, the discrepancy between mean VCI and mean vocabulary score reduced to 8.2 points (12.1). Under standard time the mean score for the NDRT comprehension section was 17.7 points lower than the mean VCI. As predicted, scores of these ADHD students improved significantly when they were allowed the ex- tended time on the reading comprehension section, yielding a discrepancy of just 7.4 (13.1). Paired t-tests on both comparisons yielded p = < 0.0001. In addition to comparing group means, we also as- sessed individual performances on these measures. Each Figure 2. Standard vs. extended time vs. IQ verbal abilities group means. participant’s score for vocabulary and for comprehension on the NDRT under standard time was compared with his scores on these measures when allowed extended time. In both cases, obtained scores on the NDRT were compared with that individual’s VCI score on the IQ test. Thus we assessed the degree to which that individual’s performance on the NDRT resembled his score for basic verbal comprehension abilities. Figure 3 shows that under standard time conditions for vocabulary items, 63.4% of the sample obtained a score on the NDRT within one SD of their VCI score; for reading comprehension items, only 42.8% were within that range. This can be compared to the normative data from the WIAT which shows that only 11% - 12% of individuals scored one SD or more below their VCI on a standardized measure of reading comprehension. When those unable to finish in standard time allot- ments were allowed the stipulated amount of extended time to finish, scores within 1 SD of their VCI were ob- tained by 72.9% for vocabulary and by 77.9% for com- prehension, much closer to the percentage in the general population that would be expected to have such a dis- crepancy. 4. DISCUSSION While many of these 145 adolescents with ADHD were able to complete the NDRT within standard time con- straints, 48% were unable even to attempt all the vo- cabulary questions and 53% were unable to attempt all of the reading comprehension questions without ex- tended time. This is consistent with our clinical experi- ence that many, but not all students with ADHD report chronic difficulty in completing tests, particularly tests involving substantial reading, within standard time limits. The high average mean verbal comprehension index scores of this sample and their solidly average mean scores for basic reading skills may limit generalizability of our results, but they do support our prediction that Figure 3. Percentage of subjects scoring within 1 sd of their iq verbal ability index standard time vs. extended time. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 79-87 85 their difficulty with the reading test used was not likely to be a result of weaknesses in basic verbal abilities or weaknesses in basic reading skills. It appears more likely that their significant relative weaknesses in processing speed and working memory, aspects of the executive functions often impaired in ADHD, contributed to their relatively low scores on our reading measure adminis- tered with just standard time. These data provide evidence that on tests involving reading longer, more complex texts under time con- straints, allowing a modest extension of time can provide individuals with ADHD opportunity to demonstrate reading comprehension abilities more consistent with their actual verbal abilities. This accommodation can help these students to compensate for the chronic prob- lems with working memory and processing speed that, for such tasks, burden many, though not all, adolescents with ADHD. Some might question whether allowing extended time on exams, particularly high stakes exams that may im- pact admission to university or graduate studies, would be providing ADHD students with an unfair advantage. This is an issue that is complex and remains controver- sial due to conflicting research findings, many due to methodological differences between studies. Lovett [31] has highlighted central issues in the controversy over extended time accommodations and has reviewed some of the evidence to draw conclusions about the way ex- tended time accommodations are currently provided. He argues for developing tests using principles of universal design so that all students can take the tests in the same format. Sireci, Scarpati and Li [32] have provided a compre- hensive review of studies that attempted to address the issue of test accommodations for students with disabili- ties and how they impact both students identified with disabilities and those without disabilities who do not receive accommodations. Their review supported the contention that extended time helps students with dis- abilities. They also found that extra time tends to impr- ove the performance of all students, not just those with disabilities. However, they noted that students with dis- abilities tend to experience more substantial gains from extended time than do their non-disabled counterparts. They suggested further research to consider whether time limits should be extended for all students on most tests. The purpose of this study was not to try to resolve the complex issues of fairness in allowing or denying use of accommodations to students with various types of im- pairments. It is to test hypotheses about the impact of ADHD-related executive function impairments on read- ing comprehension of adolescent students with ADHD and regarding the potential benefits of extended time for these students when taking tests requiring reading com- prehension of more complex texts. Our study indicated that many, but not all of our partici- pants with ADHD were unable to complete one or both sections of the NDRT within standard time allotments. This suggests that some diagnosed with ADHD do not need extended time on tests such as the NDRT, though many do need extended time to have a fair chance to show what they know and can do. These findings suggest that clinicians screening indi- viduals for ADHD should include in their evaluation specific inquiries about reading comprehension, speed of reading, memory for what has been read, and whether the individual can usually finish tests and exams within usual time constraints. In making such inquiries, it is important that the clinician ask about assigned reading as distinguished from reading of self-chosen materials in which the person has strong personal interest. As mentioned in the introduction to this paper, the situational variability of executive function impairments associated with ADHD can result in very different levels of functioning for self-chosen vs. assigned reading tasks [2]. For patients who report significant difficulties in reading speed, recall and comprehension of what has been read, or difficulty in completing tests or exams within standard time allotments, a more comprehensive assess- ment of reading, working memory and processing speed is usually indicated. Current regulations on most high-stakes testing requi- re clinical diagnostic interviews and a battery of psycho- educational testing for persons requesting extended time for such exams based on diagnosis of ADHD or a spe- cific learning disorder. Such an assessment seems appro- priate to establish need for extended time, but this re- quirement is problematic for students who cannot afford the high costs of such testing which often is not covered by insurance. The requirement is also problematic for those who do not have access to psychological evaluat- ors who have the appropriate expertise. 4.1. Limitations of the Study Findings from this study should be understood in light of limitations of the study. First, this sample is characterized by students who tended to have high average verbal comprehension abili- ties. Applicability to students with different levels of verbal comprehension may be limited and remains to be tested. The Nelson-Denny Reading Test has been criticized for having a low ceiling which does not provide ade- quate challenge for students of stronger ability who may be required in their schooling to read and take tests in- volving much more complex text than is provided by the C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 79-87 86 Nelson-Denny. Also, one study by Coleman, et al. [33] found that a sample of students with and without dis- abilities were able to obtain scores well above chance on this test without having read the passages on which the comprehension questions are based. However, despite its limitations, the NDRT is one of the few reading tests currently available that provides passages of text that extend for several paragraphs. Most other reading comprehension tests currently available attempt to test reading comprehension, even for adoles- cent and adult students, using very short passages or, in some cases, single sentences that bear little relationship to the longer, more complex readings required even of junior high and high school students, not to mention students in college or university programs. The NDRT also offers two normed versions and provides a useful measure for both a standard and extended time condi- tions. Clearly more adequate normed measures are needed, but at this time the NDRT, despite its very real limita- tions, provides a more challenging normed measure of reading comprehension for adolescents and adults than do most other measures of reading comprehension avail- able at this time. 5. CONCLUSIONS Given the findings of this study, it would seem advisable for clinicians assessing individuals with ADHD to in- quire directly about whether they are able to complete tests involving reading comprehension within the time usually allowed. If the student reports frequent inability to complete such tests, the student should be referred for a full psychoeducational evaluation, including the NDRT or a comparable measure, to establish whether accom- modations including extended time for tests and exami- nation are appropriate and should be provided. REFERENCES [1] Pennington, B.F. (1991) Diagnosing learning disorders: A neurological framework. Guilford Press, New York. [2] Brown, T.E. (2005) Attention deficit disorder: The unfo- cused mind in children and adults. Yale University Press, New Haven. [3] Brown, T.E. (2009) Developmental complexities of at- tentional disorders. In T.E. Brown (Ed.), ADHD Comor- bidities: Handbook for ADHD complications in children and adults. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Wash- ington, D.C., 3-22. [4] Anmarkrud, O. and Braten, I. (2009) Motivation for reading comprehension. Learning and Individual Differ- ences, 19, 252-256. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2008.09.002 [5] Willcutt, E.G., Pennington, B.F., et al. (2005) Neuropsy- chological analyses of comorbidity between reading dis- ability and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: In search of the common deficit. Developmental Neuropsy- chology, 27, 35-78. doi:10.1207/s15326942dn2701_3 [6] Shanahan, M.A., Pennington, B.F., et al. (2006) Process- ing speed deficits in attention deficit/hyperactivity disor- der and reading disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 585-602. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9037-8 2 [7] Laasonen, M., Leppamaki, S., et al. (2009) Adult dys- lexia and attention deficit disorder in Finland-project DyAdd. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42, 511-527. doi:10.1177/0022219409345013 [8] McGrath, L.M., Pennington, B.F., et al. (2011) A multi- ple deficit model of reading disability and atten- tion-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: Searching for shared cognitive deficits. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy- chiatry, 52, 547-557 doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02346.x [9] Arnell, K.M., Joanisse, M.F., et al. (2009) Decomposing the relation between rapid automatized naming (RAN) and reading ability. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63, 173-184. doi:10.1037/a0015721 [10] Swanson, H.L., Zheng, X., et al. (2009) Working mem- ory, short-term memory, and reading disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42, 260-287. doi:10.1177/0022219409331958 [11] Sesma, H.W., Mahone, E.M., et al. (2009) The contribu- tion of executive skills to reading comprehension. Child Neuropsychology, 15, 232-246. doi:10.1080/09297040802220029 [12] Locascio, G., Mahone, M., Eason, S. and Cutting, L. (2010) Executive dysfunction among children with read- ing comprehension deficits. Journal of Learning Disabili- ties, 43, 441-454. doi:10.1177/0022219409355476 [13] Samuelsson, S., Lundberg, I., et al. (2004) ADHD and reading disability in male adults: Is there a connection? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37, 155-168. doi:10.1177/00222194040370020601 [14] Jacobson, L.A., Matthew, R., et al. (2011) Working memory influences processing speed and reading fluency in ADHD. Child Neuropsychology, 17, 209-224. doi:10.1080/09297049.2010.532204 [15] Bental, B. and Tirosh, E. (2007) The relationship be- tween attention, executive functions and reading domain abilities in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A comparative study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy- chiatry, 48, 455-463. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01710.x [16] Leong, C.K., Tse, S.K., et al. (2008) Text comprehension in chinese children: Relative contribution of verbal working memory, pseudoword reading, rapid automa- tized naming, and onset-rime phonological segmentation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 1, 135-149. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.135 [17] Willcut, E., Pennington, B., Boada, R., Ogline, J., Tunick, R. and Chhabildas, N. (2001) A comparison of the cogni- tive deficits in reading disability and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 157-172. doi:10.1037//0021-843X.110.1.157 [18] Cain, C. and Oakhill, J. (2007) Reading comprehension difficulties: Correlates, causes and consequences. In chil- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 79-87 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 87 OJPsych dren’s comprehension problems in oral and written lan- guage. Guilford Press, New York, 41-75. [19] Shaywitz, S.E. and Shaywitz, B.A. (2008) Paying Atten- tion to Reading: The neurobiology of reading and dys- lexia. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 1329-1349. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000631 [20] Walczyk, J.J., Wei, M., et al. (2007) Development of the interplay between automatic processes and cognitive re- sources in reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 867-887. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.867 [21] Mayes, S.D. and Calhoun, S.L. (2007) Wechsler intelli- gence scale for children-third and -fourth edition predic- tors of academic achievement in children with atten- tion-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology- Quarterly, 22, 234-249. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.22.2.234 [22] Brown, T.E. (1996) Brown attention deficit disorder scales for adolescents and adults. TX. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [23] Brown, T.E. (2001) Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scales for Children and Adolescents. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [24] Wechsler, D. (2003) Wechsler intelligence scale for chil- dren-fourth edition. TX. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [25] Wechsler, D. (1997) Wechsler adult intelligence scale- third edition administration and scoring manual. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [26] Wechsler, D. (2002) Wechsler individual achievement test-second edition. TX. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [27] Woodcock, R.W., McGrew, K.S., et al. (2001) Wood- cock-johnson-third edition tests of achievement. IL. Riv- erside Publishing, Itasca. [28] Mayes, S.D., Calhoun, S.L., et al. (2009) ADHD sub- types and co-occurring anxiety, depression, and opposi- tional defiant disorder: Differences in gordon diagnostic system and wechsler working memory and processing speed index scores. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 540-549. doi:10.1177/1087054708320402 [29] Brown, J.I., Fishco, V.V. and Hanna, G. (1993) Nel- son-denny reading test. Riverside Publishing Co., Chi- cago. [30] Ofiesh, N., Mather, N. and Russell, A. (2005) Using speeded cognitive, reading, and academic measures to determine the need for extended test time among univer- sity students with learning disabilities. Journal of Psy- choeducational Assessment, 23, 35-52. doi:10.1177/073428290502300103 [31] Lovett, B.J. (2010) Extended time testing accommoda- tions for students with disabilities: Answers to five fun- damental questions. Review of Educational Research, 80, 611-638. doi:10.3102/0034654310364063 [32] Sireci, S.G., Scarpati, S.E. and Li, S. (2005) Test ac- commodations for students with disabilities: An analysis of the interaction hypothesis. Review of Educational Re- search, 75, 457-490. doi:10.3102/00346543075004457 [33] Coleman, C., Lindstrom, J., Nelson, J., Lindstrom, W. and Gregg, K. (2010) Passageless comprehension on the nelson-denny reading test: Well above chance for univer- sity students. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43, 244- 249. doi:10.1177/0022219409345017

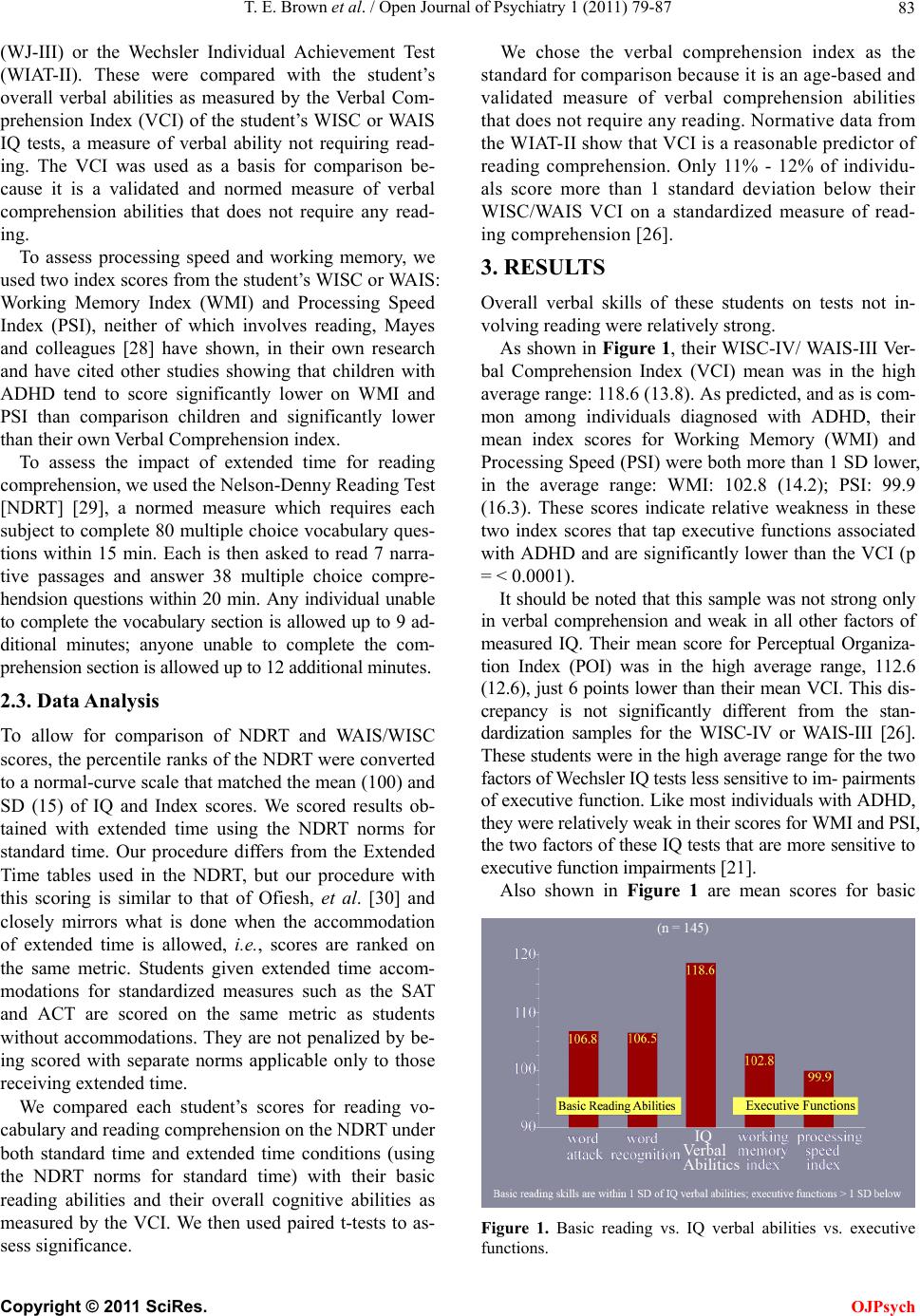

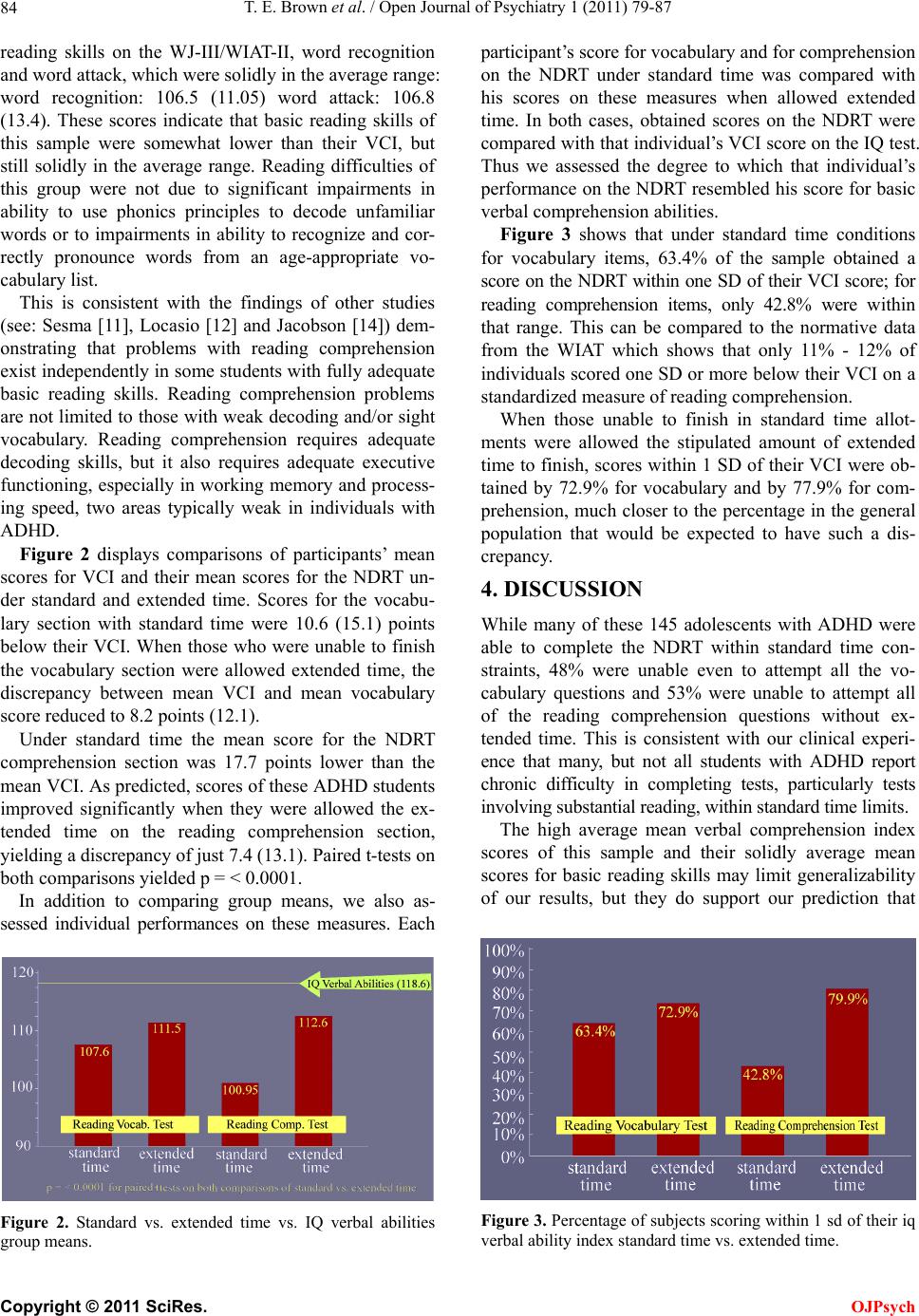

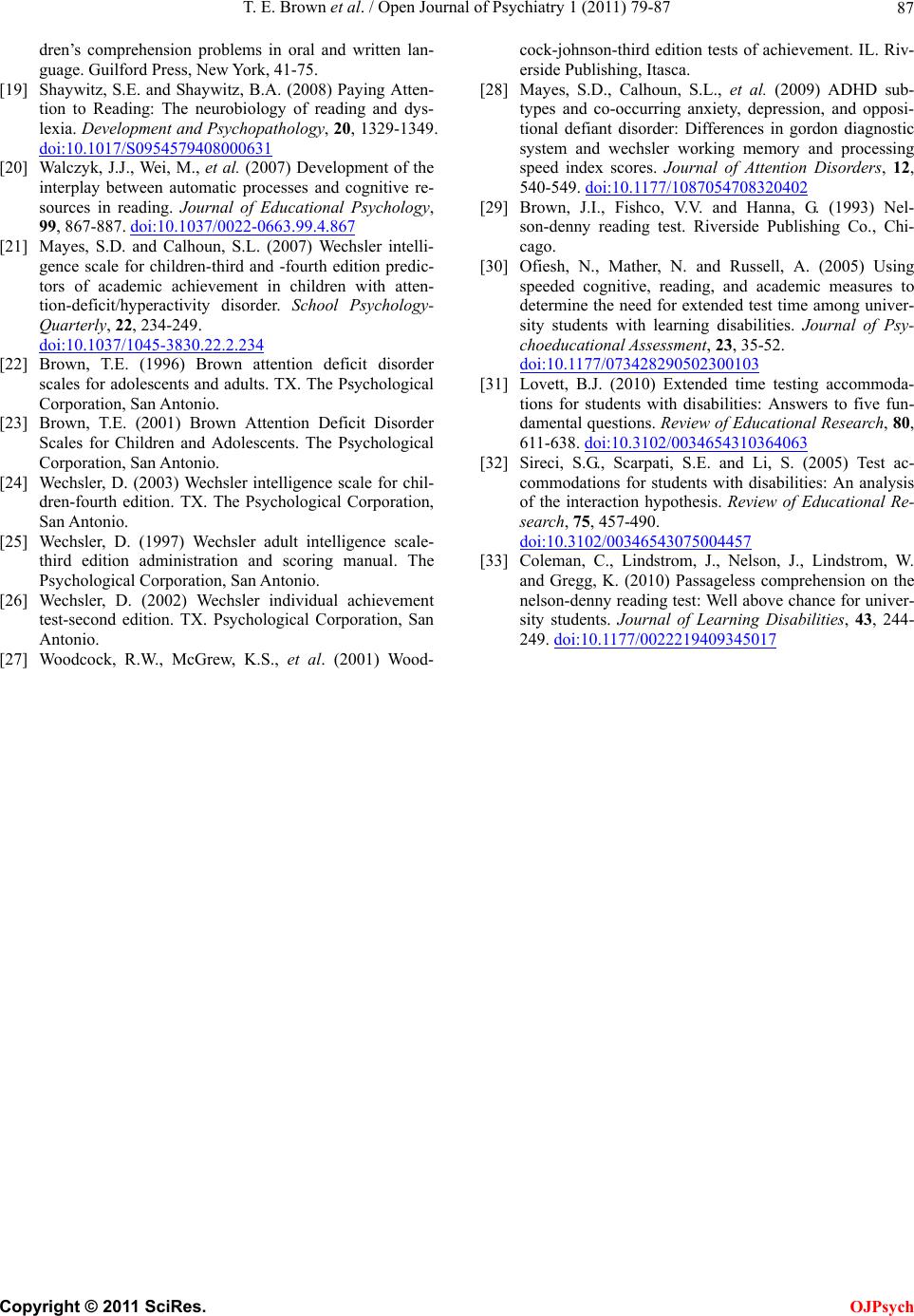

|